‘Pressure of fear’: invasion propaganda

All Australians faced an uncertain future. Until mid-1942 no one in Australia knew that the Japanese would not invade, and not for another ten or fifteen years would this knowledge become public. In the meantime, their government felt that it needed to urge them to join, work, save, produce and endure at an intensity not seen since the Great War. It is one of the many paradoxes of 1942 that even when invasion seemed likely, Curtin’s government faced the problem of motivating people to support the war effort. To do this, it chose mainly to frighten them.

Like all wartime governments, Australia’s created a large propaganda bureaucracy to inform and motivate its civilians, urging them to meet the demands governments made of them. No one could evade propaganda, either official (such as posters and advertisements) or unofficial (such as newspaper cartoons and newsreels). Propaganda built upon and shaped images that populated the minds of almost everyone. It was impossible not to imagine what might very easily happen. Thousands of readers of Fool’s Harvest would have read descriptions of the ‘Cambasian’ bombing of Sydney just a few years before. So alarmist invasion fiction created and spread an impression of the threat of invasion that retains its power today in shaping our understanding of history.

The most notorious poster was ‘He’s coming south’, distributed early in 1942. In Christopher Koch’s autobiographical novel The Boys in the Island, Francis, who represents the author, remembers a poster on Elimatta Station that showed ‘a Japanese soldier with huge teeth and terrible slit eyes, coming over the top of the globe, the shadow of his reaching hand falling on Australia; and it said: He’s coming South’.1 In fact, ‘He’s coming south’ does not show a soldier with grinning teeth or reaching hand: but it’s still a frightening image. It was unpopular at the time. Forgan Smith, the Queensland premier, objected to it, and it was withdrawn from display in that state, presumably because it would spread alarm and despondency rather than steel resolve. It was replaced there by the more aggressive ‘Go north and drive them into the sea’.2 Officials in other places, such as Melbourne’s town clerk, also declined to display ‘He’s coming south’, presumably because they noticed that it demoralised and distressed people.3

Still, as Judy Mackinolty pointed out in a pioneering article on Australian war propaganda, the image used in ‘He’s coming south’ was not so different from those seen daily in cartoons and advertisements in newspapers and on hoardings. She cited a Mick Armstrong cartoon published in The Argus in March 1942, accompanying a report of Japanese atrocities in Hong Kong. It showed a Japanese soldier, with a ‘grinning, ape-like form’, wielding a club in one hand and in the other a ‘naked woman held aloft by the hair’.4 Images such as this drew upon ideas conveyed by decades of alarmist fiction. The fear of sexual violence ran deep, and was expressed widely. In Albury, for instance, the Border Morning Mail, outraged that fifteen rather than 200 men had turned out to dig trenches at a sports ground, reminded its readers that it was ‘unlikely that the yellow beasts and ravishers of women will notify us in advance’ if they invaded.5 At the same time, Albury people could watch a Movietone newsreel in which Lawrence Impey, a British journalist, described how ‘I saw what happened after the Japanese took Nanking … Eight thousand girls taken from the safety of a college campus … Japanese officers controlled that organised rape’.6

Newspaper reports, cartoons and posters also unsettled children. Gavin Souter recalled that his reaction to advertisements, ‘particularly one which showed Japanese children doing bayonet practice on straw dummies, was not what the Government intended’. He was frightened:

If the soldiers made in Japan were anything like a drawing I had seen in the Sunday Sun – a squat, bow-legged figure in basin helmet and sandshoes, emerging apelike from the jungle … they would be no easy foe to smash.7

‘Daddy,’ a child asks in a novel set in 1942, ‘can I have a scooter for my birthday, if I’m alive?’8

The government’s approach to invasion propaganda seemed unwise to contemporaries. Marjorie Barnard and Flora Eldershaw captured the tone of the ‘pressure of fear’:

The pressure varied, sometimes attack seemed imminent, at other times the likelihood appeared to decrease. Now one argument, now another usurped the public imagination. When fear receded the leaders and politicians must bring it back, for it was a powerful lever to advance the war effort. When it increased beyond a certain point it became dangerous to morale …9

One of the most significant illustrations of how badly judged was Australian official propaganda in 1942 was the notorious ‘Know your enemy’ campaign.

‘Crazy dreams’: the ‘Hate campaign’

The ‘Know your enemy’ campaign of March–April 1942 presented the ‘Japanese character’, or at least Australian perceptions of it. The campaign would have been hard to avoid. It comprised a concentrated series of newspaper and radio advertisements running over two weeks, with the radio spots ranging from thirty-second announcements, two-minute talks and seven-and-a-half-minute broadcasts on 119 stations across the country.

The Japanese, the press advertisements claimed, were both ‘loving guardians of goldfish’ and ‘callous bombers of innocents’. The ‘hand that waved a fan’ they depicted as also holding the ‘dagger of the League of Blood’ – whatever that was. Other advertisements claimed that the Japanese had been ‘trained to hate from boyhood’ and asked, ‘Are they to ravage our homes?’ ‘We’ve always despised them,’ each advert ended, ‘now we must smash them.’ The radio spots tried to show ‘The Jap as he really is’. Segments bore titles such as ‘How the cunning Japs use religion as a weapon’, ‘Japan’s slave economy’ and ‘Japan’s evil leaders’.

One wireless script, ‘It’s a crime to think in Japanese’, gives the flavour of the series.10 It portrays Japan as, ‘with the possible exception of Germany, … the most policed nation in the world’. Hundreds of thousands of ‘Japanese Gestapo agents’ intimidate Japan’s 80 million people ‘to make certain there’s not a single Japanese who is harbouring what are known as “dangerous thoughts” ’. The script detailed the methods used by the ‘Jap Gestapo’. Their ‘usual routine’ involved whips, rubber truncheons and – curiously – itching powder, which apparently was a ‘typical Japanese torture’. ‘This is the race we are up against today,’ the narrator says, ‘a race ruled by terror; a race of regimented minds … Our job is to wake them up from their crazy dreams.’

The 22 000 Australians (and the many more other Allied prisoners) who had been captured by the Japanese had begun to find that the techniques the ‘Jap Gestapo’ – the Kempei-tei – used to extract confessions and punish defiance were much, much worse than whips, rubber truncheons or itching powder. The campaign’s authors did not yet know the full extent of the horrors that the Pacific war would expose. If they had known of these things – mass executions in China and Singapore, the torture of those taken by the Kempei-tei, the hideous biological experiments perpetrated in Manchuria, and the routine brutality of the prisoner-of-war camps – notions of decency would probably have prevented them being spoken of over the wireless.

The ‘Hate campaign’, as it was soon christened, attracted widespread debate in the press, most of it critical. The Sydney Morning Herald received nearly a hundred letters of disapproval but only half a dozen in support. Gallup polls revealed disparate feelings. Two-thirds of Queenslanders (the very people whom Forgan Smith thought would object to ‘He’s coming south’) agreed with it. But in New South Wales and Western Australia (states notionally threatened by landings) two-thirds of respondents opposed the campaign.

The campaign bothered influential thinkers too. The National Methodist Conference protested directly to Curtin that the advertisements were ‘un-Christian and un-British’ and ‘likely to undermine the people’s morale’.11 Charles Bean, who had journeyed a long way since, as a young reporter, he had predicted race war to preserve a White Australia, thought the campaign ‘un-Australian’. The ‘Hate campaign’ shows how much the Curtin Government misread the popular mood. People seemed to be more interested in knowing what they should do than in being told what they should feel. The irony of the campaign was not only that it was quite unnecessary, but that it backfired. Australians were in the main outraged, not so much by the methods used by the ‘Jap Gestapo’, but that the Australian Government should be spending time and energy telling them this sort of thing. A survey in March 1942 (before the advertising campaign began) revealed that 54 per cent of people thought that the Japanese would invade Australia and 93 per cent were already prepared to fight on. There was no need for a campaign to convince them.

Were the rest potentially those whom Erle Cox called ‘blowflies’ – prepared to accept a Japanese occupation rather than resist?12 The merchant sailor to whom Jean Devanny talked in north Queensland pointed out that ‘If the Japs won they would take over the majority of the capital of the big concerns’ but, unlike his companion, saw that they would not put capitalists to work drawing rickshaws.13 Andrew Moore, a scholar of reactionary political movements, has suggested that there was talk of ‘White Japanese’ – those who were members of the societies friendly towards Japan during the war.14 He named Sir John Latham (who thought the prospect of war remote even as the Combined Fleet gathered for the Pearl Harbor strike), the realtor Sir Henry Braddon, and Harold Darling, a director of BHP. But such speculation is unfair and groundless.

‘Life went on and people lived it’: the mood of 1942

The threat of invasion shocked Australians into thinking about what it was that they valued in their country. In March 1942 the eighth issue of the Meanjin Papers appeared – its celebrated ‘Crisis Number’. Clem Christesen, who had founded the magazine two years before, sought to define a distinctively Australian literary culture by publishing criticism and new writing, especially poetry. For all its self-conscious nationalism, Meanjin offered a critique based on both affection and hope. Christesen chose an epigram from J. B. Priestley for the title spread: ‘We should love our country, but also insist on telling it all its faults.’ The real danger, Priestley wrote, was not the critic, but the ‘noisy patriot’ who encouraged ‘orgies of self-congratulation’. This at least was a danger Meanjin avoided.

From Brisbane, the state capital most exposed to danger, Christesen asked contributors to reflect on the implications of the threat. He spoke of the possibility that his readers might soon be hearing ‘a sound that has never before been heard in Australia – the roar and bark and thunder’ of Australians ‘defending their native country … stubbornly, bitterly, courageously’. But Christesen admitted that Australians seemed to be facing this test ‘without a vital dominating dynamic spirit’. Instead, he saw ‘disunity of purpose and terrible confusion’.15

Vance Palmer, the veteran nationalist novelist and critic, added his reflections in a piece entitled ‘Battle’. He too imagined that soon Australians would ‘make every yard of Australian earth a battle-station’. He saw virtue in this coming conflict, believing that Australians would emerge from the crisis ‘spiritually sounder … surer of our essential character’. Palmer reflected upon ‘the Australia we are called upon to save’. He admitted the shallow roots of Australian culture, Australians’ often half-hearted attachment to unlovely suburbs and ‘higgledy-piggledy towns’.

If Australia was conquered during what he described as ‘great, tragic days’ to come, Palmer thought, ‘some sort of normal life would still go on’. (‘You cannot wipe out a nation of seven million people,’ he wrote – ignorant yet of Hitler’s near success in doing exactly that in the Ukraine and Poland.) In that case, ‘not everyone could be employed pulling Japanese gentlemen about in rickshaws’. But then Palmer turned on those (such as readers of Inky Stephensen’s Publicist) who might have imagined that they could probably get by: ‘If anyone believes life would be worth living under [the Japanese] … he is not worth saving.’

But life was worth living, whatever the threat or the reality. Marjorie Barnard and Flora Eldershaw described how ‘panic went like a shiver through the community and passed’. But, they continued, ‘Life went on and people lived it.’16 Bettie Whiteman’s husband was a flying instructor at Archerfield in Queensland. They heard news of Pearl Harbor while on holiday at Surfers’ Paradise – then a small coastal village. Bettie recalled that they thought ‘it looked like a distinct possibility that the Japs would land on Australian soil’, and that her neighbours dug bomb shelters and buried their valuables. As the situation became more grave, Bettie’s husband became concerned ‘because of the news coming through of atrocities being committed by the Japs’. He worked out a plan that ‘if the worst happened’ he would squeeze Bettie and their daughter (then a toddler) into a Tiger Moth trainer and ‘fly us to a safer spot’. Like many husbands, Bettie’s planned to ‘give me his service revolver to use if capture was imminent’. She would use the gun on her daughter and herself. ‘It sounds a little melodramatic now,’ she conceded in 1990, ‘but it was all real and frightening then.’17

The invasion scare brought out partisans of all stripes. Hundreds of people wrote to Curtin, seeking his help on probate and child allowances, offering to volunteer, seeking exemption from military service, suggesting that the Zeros brought down over Darwin be presented to the ‘National War Memorial’ (they weren’t). He received a letter from a lady in Arncliffe criticising railwaymen, and then a second letter asking him not to mention her name because her husband (a railwayman, perhaps) would be annoyed. He received pages of pamphlets relating the crisis to Biblical prophesies and to causes of all kinds. Wowsers lobbied over the licensing of barmaids (which infuriated both temperance advocates and those who wanted state laws left unchanged) and the introduction of wet canteens into military camps. Curtin, a puritan since overcoming alcoholism, embraced the austerity that Australia needed ‘in her darkest hour’. He urged civilians to join voluntary organisations rather than go to the races, to the pub or ‘golfing all the weekend’.18

Of course, ordinary life continued: people went to school and work; met, married, made love; cleaned the oven and fired up the copper for the weekly wash. And the threat of invasion did not interfere with the ferment of ideas that would shape Australian society in years to come. Indeed, it encouraged them. Meanjin continued to publish verse and articles defining and exploring national life: Menzies made the broadcasts that became the Liberal Party’s manifesto, The Forgotten People, in May 1942.

But something was present that year in every Australian home that hadn’t been there the year before and would not be there the following year: the smell of fear. Those who lived through that year will remember the posters warning, urging, cajoling, inspiring. They recall the precautions against attack – the sandbags around windows, the slit trenches in schoolyards and playgrounds, the camouflaging of buses, the barbed wire on beaches and the arrival of anti-aircraft guns and Americans. They recall the family stories: how a mother in Perth bought a cow to provide milk when the children would be evacuated; how Dad practised with a .22 rifle; how a soldier serving in New Guinea warned his wife to drown his daughters if the Japs came.

Australians were understandably nervous early in 1942. A young Sydneysider, Tess Worthing, about to begin a clerical job with the wartime Liquid Fuels Board, pretended to read a headline in a newspaper, saying to her mother at breakfast, ‘Darwin’s been invaded!’ Her mother went ‘white as a sheet’ and then, when Tess laughed at the joke, rebuked her because ‘she was quite sure we were all going to be either bayoneted or ravished’.19 (Perhaps Tess’s mother had listened to the Japanese shortwave radio propaganda, which reported that it had ‘thrown the whole of Australia into a state of unholy terror’.20 Axis propagandists – without evidence – and historians – with lots – essentially agree on this point.)

If the stories of demoralisation and panic were all true, then Australians could be seen as failing the first great test of national survival in the face of direct threat. There is little of the bulldog breed about these stories, no spirit of the Blitz here. Many stories were told, at the time and later, of people fleeing to stay with country relatives, boarding up shops ‘for the duration’ or walking away from homes and businesses. Some of these stories are true, some exaggerated or ‘unproven’. All demand further investigation. For example, reports of Sydneysiders, often said to be Jewish, fleeing to the Blue Mountains remain anecdotal. (Jewish Australians could not win: anti-Semitic hearsay had them buying up properties in Sydney’s supposedly vulnerable eastern suburbs.) We still need to tease myth from reality: it is fatuous to argue that the perception is all that matters – the facts do too. These stories are woven into the fabric of thousands of families’ memories. It is hard to hold out against them: surely the threat must have been real?

Yes, it was real, but it was a reality in the mind, rather than of fact. We need to keep the two things before us in trying to understand the experience and the memory of 1942. The advertising credo that the perception is the reality does not apply here. Certainly the feeling of threat was real enough in Australia in 1942, and we need to understand just how real that fear was. It was the most crucial year in Australia’s history. If the war in the Pacific had gone differently, then perhaps Australia’s history may have followed the course charted by the novelists who had depicted Australians resisting invasion. Australians now prepared in earnest for invasion.

‘Denial of resources’: the scorched-earth policy and its effects

Mary Gilmore’s defiant poem declared, ‘No foe shall … sit on our stockyard rail.’ Indeed the rails were to be burned, along with all productive resources, denying an invader anything useful. Bill Wentworth’s ‘burnt earth’ idea became an official strategy. At a rally in February celebrating the Red Army’s twenty-fourth anniversary, Eddie Ward, the minister for Labour, urged the adoption of a ‘scorched earth’ policy in emulation of the Soviet Union.21 It became an official policy in April. Across the country, but especially on the north-east coast, army and Volunteer Defence Corps (VDC) units and local-government engineers began preparing for the destruction of bridges and the removal or slaughter of livestock. At Kyogle, on the north coast of New South Wales, Harry Flower recalled that ‘an official’ visited the dairying town to organise a scorched-earth program. ‘He must have been a good talker,’ Harry remembered, ‘because he really put the wind up everyone.’22 But the official needed no special gift of oratory in a climate in which invasion seemed to be a real possibility.

Many communities met to decide how they would destroy the creations of generations. Les Sullivan, then a student at teachers’ college in Armidale, went with his father to a meeting at his home in Clybucca, near Kempsey. ‘An official’ – one of many abroad that year – told the dairymen how they were to run cars and tractors until they seized, flood boats and drive their herds over the ranges to the west. ‘I wonder if there will be a farm to come home to’ in the September holidays, Les wrote.23

Most local-government areas worked out evacuation plans, some preparing to despatch children and some mothers to safer areas, some to receive evacuees. Naturally, plans were most urgent in Queensland. At Ingham the local council arranged for families to travel over the ranges to Mount Fox, 60 kilometres west, where tinned food had been dumped (and after the crisis, it seemed, forgotten). Women and children from Proserpine actually did go west to Aramac, where they endured a plague of huge, ferocious rats. Towns to the south had various plans, depending on where the Japanese actually landed: Maryborough, for example, would either evacuate its civilians or provide refuge in case of a landing further north.24 While some of the detail of these plans was questionable – how small country towns dependent on imported food could house large numbers of evacuees was never satisfactorily resolved – they were understandable in the circumstances.

Many shires and municipalities had plans to evacuate women and children, but these dated from the late 1930s and were not an impromptu response to the crisis of early 1942. Kay Saunders and Lynette Finch have shown that those seeming most at risk from a possible invasion – the residents of northern Australia – were those least able to leave easily. The areas most at risk were mainly without railways (and in Queensland without links to the interior), while in north-west Australia bad roads limited everyone’s mobility. They quoted examples of journeys early in 1942 that suggest real evacuation would not have been possible. The journalists Cyril Longmore (a veteran of Quinn’s Post on Gallipoli) and Harry Potter slipped for 30 kilometres along the ‘highway’ to Broome in the wet. On one day they made 11 muddy kilometres, on another found the road under running water for 5 kilometres. ‘Runaways’ from Broome were forced to return as ‘tricklebacks’.25

Some of Mr Curtin’s correspondents took the idea of scorched earth literally. Jeff Miller of Penong, on South Australia’s remote west coast, wrote in March, offering his thoughts on how an invasion might be met. He faced up immediately to the fact that ‘without doubt Australia is about to be invaded by the Japs’. He thought they would probably land in at least two places – Perth and ‘some northern port of Queensland, say Cairns’. (From Perth, he explained, they could use the transcontinental railway: ‘the Jap as you know … is a quick goer.’) If the Japanese did decide to exploit the railway line, though, Mr Miller advised that ‘a scorched earth policy would be a great factor in deterring him’. He knew the line well, and suggested that the spinifex and mallee country between Ooldea and Wynbring (in the sandhills of the Great Victoria Desert, just before the railway begins its long straight) would be the ideal place to stop them. Blowing up the line and ‘a plane or two dishing incendiary bombs’ would do the trick. ‘That desert would be an inferno in no time,’ he predicted. This would ‘give the yellow invader all the hell he wants and deserves’. This should have been done at the war’s outbreak, he thought, but he reassured Curtin that ‘you have the whole of Australia behind you’.26 That, at least, was a realistic statement.

‘Yellow spies’: rumours of war

The imminent threat inspired a bizarre creative response too. On 4 February a Mr Joseph Guerin of Murrumbeena, Victoria, applied for a trademark on a game called ‘Invasion’. It was played with cards, some representing weapons (such as bombs) and others defensive measures (such as ‘blackout materials’). A ‘Mr Wisdom’ card could be used to negate any offensive card, except ‘The Gossiper’, ‘against which,’ Mr Guerin warned, ‘there is no defence.’27 And with news censored and at times mistrusted, invasion rumours spread.

Understandable ignorance, fear and simple lack of firm knowledge fuelled invasion alarms and scares all around the coast. Speculation, hearsay, exaggeration, rumour and invention became a part of the story of 1942. Rumours became so destructive that in early May the War Cabinet prohibited ‘unauthorised and speculative statements regarding operations by the enemy against Australia’.28 Fiction and prediction mingled with news and commentary, positive-thinking with doomsaying, and silence and half-truth with fearless reportage. The public record of 1942 encompasses the mendacity of the ‘Hate campaign’ and the honesty of Damien Parer looking the audience of his film Kokoda Front Line! in the eye. The rumours and furphies of 1942 live on tenaciously. It is important to understand where they originated.

Rumours spread among coastal communities, especially in the north. In St Lawrence, on the central Queensland coast (near where George Mitchell’s The Awakening was set), reports arrived of Japanese submarines surfacing and sending sabotage parties ashore to cut the coastal railway. The stationmaster sent a man on a bicycle up the line to investigate (a sign of his scepticism, perhaps). To everyone’s relief, he returned, reporting that ‘the mysterious light was only the moon shining behind Wood Duck island’.29 A family in the ranges west of Tully received a call to evacuate in a hurry, only to learn that an Aboriginal tracker had damaged his reputation by supposing that a footprint he had found was that of a Japanese paratrooper.30 In nearby Cardwell (one of the few towns to enlist Aboriginal men in its VDC unit), speculation drew on pre-war suspicions of Japanese espionage. One man thought that ‘If the Japs know as much about our coast line as we think they do, there’s only one place they’d hit … Cardwell’, because road, rail and telegraph lines ran within a few hundred metres of the beach.31

The prospect of invasion fostered suspicion, not least because official propaganda encouraged prudence that could easily grow into mistrust. At the height of the Japanese threat the crime novelist W. T. Stewart released Yellow Spies, a complex and unsatisfying tale about a beautiful, smart Chinese woman detective, Gaff Lee, who foils a Japanese plot aboard a British merchant ship in the South China Sea. The improbable details of the creaking plot do not really matter: I wasted hours trying to work out who was impersonating whom before they were knifed, shot or strangled. But the novel was timely because it reminded readers of Japan’s supposed espionage network of ruthless ‘Ronin’. ‘Japanese espionage is the most thorough and despicable in existence,’ Gaff Lee reminds the obtuse but obliging ship’s captain. An entire chapter of the book reproduces an account of the Rape of Nanking, based on foreign missionaries’ accounts published in the Readers’ Digest. The descriptions of torture, rape and murder confirmed, if any proof were needed, Japan’s brutality, but the novel gave a seriously flawed impression of Japanese wartime espionage. No Japanese agents operated in Australia after the security services interned both Japanese nationals and Japanese Australians in December 1941.

Even a mind as sharp as Mary Gilmore’s fell into spy mania. In June 1942 – soon after the submarine raid on the harbour she could see from her window in Darlinghurst Road – she wrote to a body she vaguely called the ‘Intelligence Department’, drawing its attention to a block of flats in nearby Bayswater Road. The building, she reported, was painted in a distinctive irregular pattern. Could it be used as a ‘land-mark from the sky’ for bombers flying overhead, could it have been accidental ‘Or could it be “significant”?’ she asked.32 Equally bizarre incidents can be found in the war diaries of VDC units across the country. At Iron Knob in South Australia (the source of all of Australia’s iron ore, but also as far from Japanese bombers as could be) neighbours dobbed in a man named Jack Anderson. Doubtful of his Norwegian background, they told VDC officers that he was collecting information on the movements of ore ships. What he did with it they could not say. Anderson, the little town’s ‘unofficial mayor’, fell foul of small-town malicious gossip.33

No wonder rumours abounded. Gavin Souter, an unusually alert boy, recalled 1942 as a time when the ‘atmosphere was heavy with tension and rumour’.34 These rumours carried the popular fear of what the Japanese were capable of. From reports of the China war, and news and propaganda filtering out of Hong Kong or Singapore, people knew what to expect. They had also read accounts of Japanese invasions of Australia before. Ann Dickason, who worked in the motor industry in Melbourne, remembered that ‘stories were spread about the Japanese, who would enslave our men and breed a tall race with the Australian women’.35 This, of course, is exactly what Erle Cox had described in his novel Fool’s Harvest.

Just as the threat was seen most immediately in the north, so rumours of invasion were most prevalent there. Commonwealth Investigation Service officers reported in 1942 on ‘Ivan Steele’, also known as Suzuki, who had worked for twenty years in the area as a motor mechanic. ‘He knew every bore water hole and track from Camooweal to Quilpie,’ they reported, and had once taken 1200 cattle on a 2400-kilometre drive with the loss of only two beasts. The implication was that if Japanese troops were to advance south from the Gulf into western Queensland (as Kenneth Mackay had imagined ‘Mongols’ doing fifty years before) then Suzuki would have made a skilful local guide. He, like every other Japanese Australian in Tennant Creek, had been interned in December 1941. But among the Japanese spies was a ‘capable commercial espionage agent’ named Umeda. He had spent a long time in the district, negotiating cattle and ore shipments, as had ‘a few alleged air experts’ who had reconnoitred seaplane anchorages at Karumba and on Groot Eylandt.36 He would have been interned like all Japanese Australians, had he not got away before December 1941.

The Queensland Gulf country had always been a popular spot for speculation. In 1942 Lieutenant Colonel Robert Wake speculated on a possible invasion scenario. He began by ‘placing [himself] in the position of a Japanese General Staff Officer of a division about to attack Australia through one back door’.37 The landing would occur at the unfortunately named Port McArthur, an uninhabited mangrove-fringed bay in the Sir Edward Pellew Group on the south-west shore of the Gulf of Carpentaria. The Japanese objectives, he thought, were to seize enough territory to make a bargaining counter, to obtain necessary raw materials (wool, zinc, copper, iron and – curiously – sugar for alcohol) and to establish bases for air attacks on Sydney and Newcastle. He assumed that the Japanese held air superiority over the invasion beaches and that only ‘sporadic’ Allied raids could interfere with the landings. He anticipated the landing of a ‘complete Japanese Division fully mechanised’, with an ‘air arm … on a major scale ensuring refuelling from the air if need be’.

Colonel Wake’s Japanese division was going to advance across the Barkly Tableland over 600 kilometres to Mount Isa, and then push a further thousand south-eastwards, through Winton, Longreach and Blackall to Charleville. The only problem Wake foresaw was that monsoon rains meant the operation had to be completed by the end of November. That any Japanese force could land in the Gulf, move with assurance so far over unsealed roads over such country and at such a distance and be resupplied (by air no less) is inconceivable. But the expectation that the Japanese could well land in the Gulf explains the events of April 1943.

Observers on stations on Queensland’s Gulf coast had reported early in that month lights and even a sighting of a 30- or 40-foot vessel near the mouth of the Nassau River on the south-eastern coast of the Gulf. In the early hours of 11 April a VDC patrol reported Japanese troops landing from a barge at Nassau River. The reports spread chaos. Panicked by rumours of Japanese aircraft flying over the coast and vessels sighted in the Gulf, people packed their bags and headed south. North Australia Observer Unit and VDC patrols went out on horses looking for the Japanese but found, a researcher disclosed, ‘nothing, no landing site, no landing barges, no footprints, no Japanese.’ It seems that an Aboriginal boy on Inkerman station explains the real story behind the supposed landing. He reported to the manager at Inkerman that he had seen a Japanese boat with Japanese on the beach to the north. The station manager got on his pedal radio and called Cloncurry, and that is how the army heard about it. Meanwhile the RAAF instructed three young pilots to fly their Wirraway aircraft over Inkerman. Seeing no one about, the pilots flew low and shot up a shed, and the station people who were hiding thought that Japanese aircraft were attacking. VDC officers believed that the boy may have seen a submarine surfacing in the Gulf (although the water is shallow, and there was no corroboration of the report). The panic of the ‘Gulf scare’ subsided but many families did not return until after the war.38

This all seems farcical, but we need to understand how vulnerable all Australians felt in 1942. If the Japanese sailors watching the Yarra sink beneath the waters of the Indian Ocean had steamed south, the next coast they would have come to was Australia’s. Except for scattered ships and weak garrisons at isolated points, there was little between the Japanese navy and Australia. It really did seem as though Australia would soon have to resist invasion.

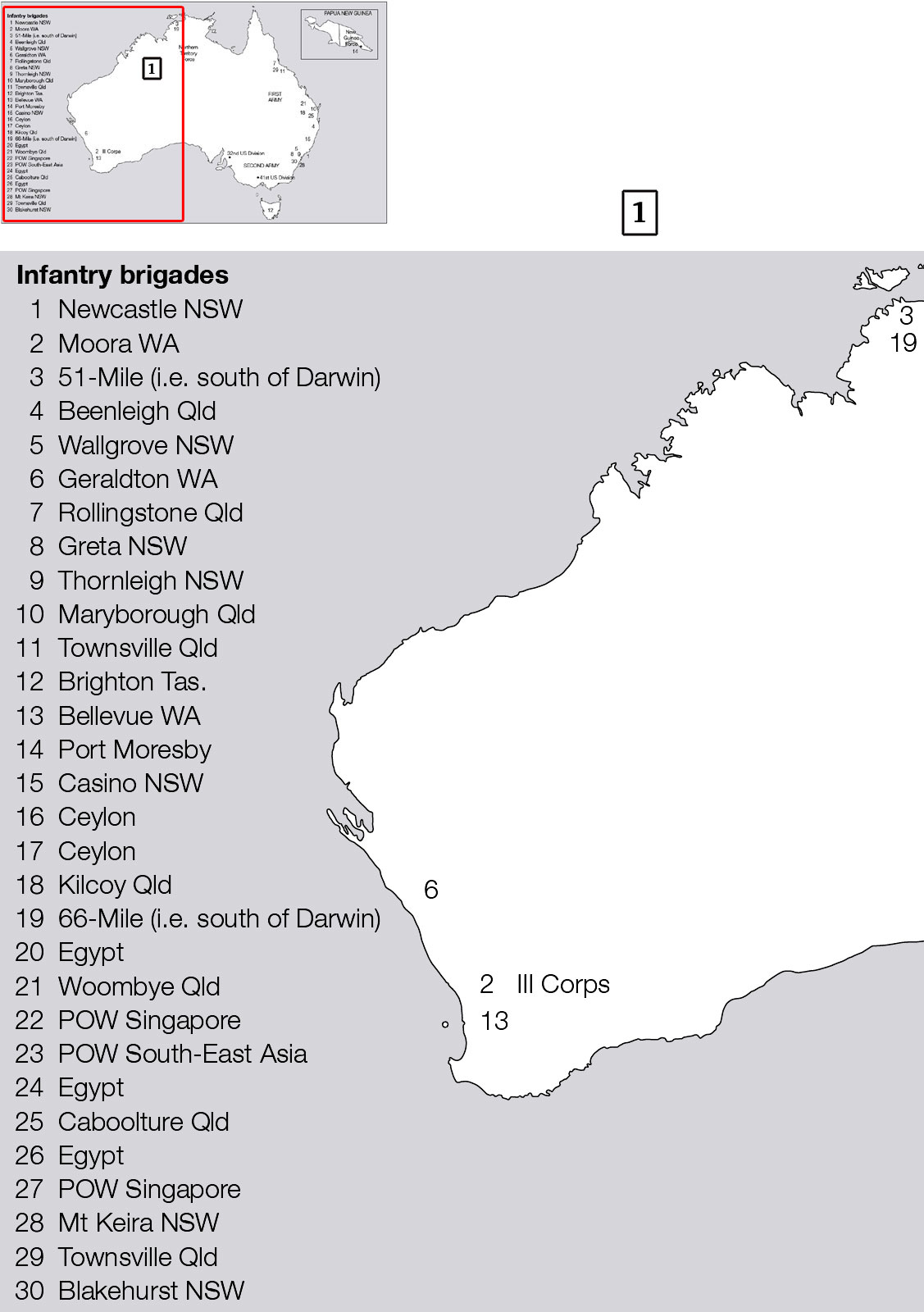

Australia, showing the distribution of major defence formations, 1 July 1942