In October 1966 a group of Old Order Amish bishops began a process to create a new structure that would either ultimately protect the Old Order or fundamentally change the internal structure of the group beyond recognition. They did not necessarily think of the long-term ramifications, because they did not know the path they were to take. They simply gathered at the Graber schoolhouse in Allen County, Indiana, to discuss the proposed changes in the draft laws. These Amish bishops were not arguing for political opposition to the Vietnam War specifically or even to war in general. And although they would have preferred not to have to participate in alternative service, their objection was to the structure of the I-W system, a new system of alternative service for conscientious objectors begun during the Korean War.1 This system emphasized individual service and placed Amish men into positions where they did not have community support and could be enticed by worldly entrapments or seduced by women of other faiths. The bishops found this “unsatisfactory and harmful to our Amish Churches” and felt they could “hardly continue with the present setup.”2

The bishops formed a delegation, composed of one man from each Old Order Amish district, that would go to Washington, D.C., to explain the Amish position and negotiate for change. They later succeeded in their negotiations, but their very success instituted a fundamental change in the Amish cultural fencing. Until this point the Amish relied extensively on local Mennonites to speak on their behalf; the new committee would now function in that position. The bishops considered this split purposeful: “[T]he feeling is that the Old Order Amish are following too closely in the steps of the Mennonites which is undermining our Amish way of life.”3 They all realized that protection of cultural boundaries might be necessary, but they had to be mindful of the consequences of their actions. They would not allow this new committee “to infringe upon or dispute or consul [sic] differences of ordnung or home rule from the various communities.” The Old Order Amish structure had to remain congregational.4

What led to the meetings in 1966 can best be understood through a consideration of events following World War II. The Vietnam War and its threat to the community through the draft was only a small part of a growing need to selectively negotiate cultural fencing with outsiders. Crisis in school attendance, economic employment, Social Security, and health regulations created an atmosphere of frustration within the community that only the community could address.

At the end of World War II the Amish were in a far healthier position with their neighbors than they had been at the end of the previous war. Their neighbors had grown to know and accept the Amish, but they still did not understand them. The non-Amish citizens of LaGrange jumped from viewing the Amish as totally different to being just like them, and when the Amish proved to still be different, the atmosphere of tolerance began to disintegrate.5 Local misunderstanding appeared first in 1948, when the Goshen New Democrat reported the pending arrest of a farmer (and Amish bishop) for keeping his demented daughter chained to a bed. The paper continued in that vein by referring to Bishop Samuel Hochstetler as a religious tyrant.6

In truth, Lucy Hochstetler was the middle-aged daughter of Samuel and Magdelena Hochstetler. She had developed severe mental problems many years earlier. Her parents had scraped together the money in 1926 to take her to a specialist in Chicago, with whom they continued to consult for some years thereafter. After Magdelena’s death in 1947, Samuel resorted to copper chains to keep the stout, violent Lucy from hurting herself when he could not be there to watch after her. Apparently Samuel was doing the best he could and trying to avoid having to put Lucy in a hospital, but his own health was failing. Someone reported him to the sheriff’s office, and the officer who came out to investigate found Lucy chained. Samuel was arrested. He put up no defense and was sentenced to six months in jail. His daughter was institutionalized, and even though she underwent a lobotomy, she remained violent and locked up in a Goshen nursing home. Samuel became a model prisoner and, through continued efforts of influential Mennonites in the area, was eventually pardoned by the governor.7

The local reaction to this event is remarkable. The Goshen newspaper fabricated a story that Lucy had wanted to marry someone outside their faith and her parents had restrained her to keep that from happening. Over the years, the newspaper continued, her mental health had slowly broken down. Although the story was exposed as untrue, the paper never printed a retraction.8

During this same period LaGrange County citizens became increasingly irritated over the behavior of some Amish teenagers, who were getting into local difficulties after imbibing too much alcohol.9 Apparent leniency on the part of Amish parents galled the “good citizens” of LaGrange. Actually, Amish parents were also worried, but they saw public schools as a growing area of concern.

After years of a holding pattern created by the Great Depression and the World Wars, Indiana began aggressively consolidating its schools, a practice started in the 1920s. A study of the Indiana Public Schools, published in 1949, emphasized that “small schools must be recognized as ineffective and inappropriate to an adequate system of secondary education.”10 It also recommended, to the continued dismay of the Amish, that the school-leaving age be set at eighteen or the completion of the twelfth grade; this recommendation was not approved, and the school-leaving age remained at sixteen.11

The Elkhart County school system closed its last one-room schoolhouse in 1948, leaving only consolidated schools that required busing. The Old Order Amish in Middlebury banded together to purchase the schoolhouse when it came up for auction in August. Although there was initial concern that the community would have problems bearing the heavy financial burden of paying public school taxes and supporting an Amish school, they managed. For the first school year, they hired a retired Mennonite schoolteacher, whom they knew because he had worked as a thresher in the summer months. He could teach but was hard of hearing. Although parents were relieved, they soon realized they had to do something about a teacher who could not hear his students.

Eli Gingerich, an Old Order Amish man from Plain City, Ohio, came to the rescue of the school. He moved to Middlebury the year before the parochial schoolhouse opened so that his family could be near his wife’s parents. Having completed some years of high school education in Ohio, where it was required in the 1930s, he thought seriously, but privately, about offering his services. He was therefore startled one Sunday when a deacon, who was also on the Amish school board, suggested that he teach at the school. Gingerich agreed, completed his high school equivalency exam (GED), and taught for two years.12 After that time, the board hired a Mennonite minister’s wife from Goshen. Although she was supposed to teach only temporarily, she stayed for six years. When the local superintendent investigated the school, he was impressed with the discipline and the children’s interest in learning.13

The Amish in LaGrange and Elkhart Counties came late to the parochial school movement. Such schools already existed in Ohio, Pennsylvania, Iowa, and other parts of Indiana where there were small Amish outposts. For several years after the Middlebury school opened, it was the only one in the area. Eventually, as one-room schoolhouses closed in LaGrange, the use of parochial schools grew, but nine years elapsed before a second school was built in 1957.14

If it had not been for the closing of the public one-room schoolhouses throughout the nation, the original compromise of the 1920s might have lasted in Indiana. The center of difficulty was not in LaGrange, an Amish settlement far larger than elsewhere in the state, but in areas mostly untouched by the education difficulties of the 1920s. Real trouble over compulsory school attendance first erupted in Adams and Allen Counties, not in LaGrange or Elkhart.15 Although trouble would eventually find its way to Shipshewana, there is no record that anyone suffered the same problems found in Allen or Adams Counties in the 1950s or, even worse, in Hazleton, Iowa, in the 1960s. In Hazleton the strong-arm tactics of truant officers frightened Amish schoolchildren, who ran into neighboring cornfields on one occasion and on another met authorities with passive resistance, singing “Jesus Loves Me.” These events made national headlines and the evening news.16

In the 1950s the Budget was filled with accounts of problems in Adams and Allen Counties.17 Ironically, some of the problems in Adams County stemmed from the building of parochial schools rather than absence of Amish teenagers in the high schools. Just as in LaGrange County in the 1920s, Adams County officials worried about the loss of state allocations and about the quality of education that these children were receiving.18 In July 1959 the Budget reported that the Amish in Allen County were building their own school. Previously, an Amish group in Adams County had asked permission to build a school, but the group was turned down; they simply built one without bothering to secure permission.19 The new school, near Berne, opened in September of that year.20 By the next week the Budget reported that the state planned to take action against the Amish in Allen and Adams Counties. The article added that ten people were under court order to send their children to school.21 In December the story reemerged when an appeals court upheld the Amish stance and overturned their convictions.22

Although Allen and Adams Counties remained the most interesting to the LaGrange Amish, the Budget continued to report difficulties over schools in other states.23 At the same time, the Ohio Board of Education was trying to close down the Ohio Amish schools, because they were worried about the lack of certified teachers.24 And in Pennsylvania, formerly a hotbed of problems, the state attorney general reached a compromise with the Amish, allowing Amish children to attend vocational schools in lieu of completing the regular high school curriculum.25

As the next decade progressed, the issue reached fever pitch in states such as Maryland, Kansas, Iowa, Ohio, and Wisconsin.26 Rev. William Lindholm, a Lutheran pastor from Iowa who was serving in Michigan, was horrified at what he saw. He firmly believed that various state agencies were infringing upon the religious rights of the Amish. He organized the National Committee for Amish Religious Freedom and was joined by people of many religious faiths. In 1972 the group sued the state of Wisconsin on behalf of the Amish; the Supreme Court eventually heard the case.27

Little evidence remains concerning the school issue in LaGrange. A letter to the Budget in 1959 discussed the issue in detail and pointed to the consolidation of the schools as the source of the problem. The writer conceded that state officials were aware of the issues and were building a four-room school in LaGrange that would have two grades to a room, specifically with the needs of the Amish in mind. This school “would require electricity, which we could do without. However, in a recent meeting it was agreed upon to build as near to our standards as possible.” Although he acknowledges that there were some local Amish pushing for a parochial school, the writer viewed that position with suspicion. In his opinion, the school system (“the big boys”) had compromised, and so should they. Finally, he reminded readers that Amish in other areas were serving time in prison, which was “no place for no Christians,” over their stance on education.28

In January 1967 Eli Gingerich wrote to the Budget about the school situation. He stated flatly, “We have been having some school problems in LaGrange County, especially over vocational schools.”29 Richard Wells, the new state superintendent, had called a meeting of Amish leaders, state representatives of their districts, and school officials, both public and parochial. They met on 30 December 1966 at an Amish school in Allen County. Gingerich reported that the Amish gave Wells an account of their beliefs and objectives and presented their idea for a vocational school. Wells promised to try to work out a reasonable and fair compromise, and, indicating how much the news coverage of events in Iowa had affected everyone, “He assured [us] there would be no chasing of children in corn fields, but hoped rather that the state of Indiana might take the lead and set a standard of sound government.”30

The state of Indiana compromised with the Amish before the Yoder case even reached the United States Supreme Court. These articles of agreement, published in 1967, granted the Amish permission to operate parochial schools based on several stipulations: The Amish were required to form a local school board that would work with the State Executive Committee; build and maintain schoolhouses according to approved plans and standards; abide by a school calendar; faithfully keep records of enrollment, attendance, and grades; provide appropriate instruction at each grade level, primarily in English; and employ teachers educated through the eighth grade who had passed the GED. Once they were past the eighth grade, the agreement required Amish students to enroll in a vocational training course until age sixteen. State superintendent Richard Wells, committee chairman David Schwartz, and the six members of the Amish State Executive Committee signed the final page of the agreement.31 The National Committee for Amish Religious Freedom hailed the Indiana Plan as a great success.

The Indiana Plan appears to have worked well. By 1998 Gingerich reported seventy to eighty Amish parochial schools in Indiana. He added that most schools now have two teachers, with the more experienced teacher acting as a mentor for the other.32 Notably, the number of Amish schools remains a smaller percentage relative to the Amish population than found in other states. About half of Indiana’s Amish children attend the local schools, a testament to the flexibility of the local school systems.33

At the end of World War II, in the eyes of the government and their neighbors, the Amish temporarily shifted from being desirable, frugal citizens to being backward, uneducated farmers who were resistant to change. Resistance to technology, continued reliance on small farms, and emphasis on family labor profoundly disturbed the local agricultural representatives. Yet this stereotype of a group of farmers who would not adapt and change is incorrect. Just as they had shifted to growing mint before World War II, so too did they seek new ways of farming following the war, when mint was no longer profitable. While the Amish had always been quietly tied to the market economy, they had been and continued to be constrained by a limited number of choices. They could not jeopardize the well-being of the community and its Ordnung.

During the 1950s LaGrange Amish farmers began experimenting with poultry farms in large compounds. The Lambright family appears to have been the largest holder; they hired other Amish people to work with them. A letter from Emmanuel Miller to the Budget on 29 May 1958 refers to “Hatchery #1” as being under his care. The hatchery included 2,300 layers, which he hoped would go up to 5,000. Indeed, another letter from Miller in July 1958 refers to 4,000 newborn baby chicks, with 6,000 more on the way. The same letter mentions another henhouse with 12,000 hens, which was cared for by another Amish family. Miller got his wish for more layers when he received another 8,000 hens on the day he wrote a third letter to the Budget, which was printed on 7 August 1958.

The shift from farming to agricultural enterprises picked up momentum during the 1950s, yet some small side businesses, both endemic and essential to a farming community, had always been there. There had been, and continue to be, blacksmiths in the area, as well as mechanics (on approved machinery), carpenters, buggy shop owners, and day laborers.34 Women had always tended the gardens, sold some vegetables, and raised a few chickens. After World War II, however, these microenterprises exploded and changed the shape of the community.

Most of the changes arose out of a combination of unfilled community needs and marketable skills of individuals.35 As the Amish found themselves unable to purchase items they had long taken for granted, they began to make some of these items themselves. Certainly that was the case with blacksmith shops that expanded into making simple household and farming equipment that was no longer available. Women took the next step by selling goods outside the immediate community; from marketing eggs or vegetables, they expanded into dried and fresh flowers, dry goods, and quilts.36 And, as the world shifted its perception of the Amish from old-fashioned, out-of-step farmers to quaint relics of a gentler, simpler age, Amish men took advantage of their carpentry skills to sell simple items to tourists.

Certainly by 1995 Amish enterprises made up a large segment of the Old Order economy in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.37 A few years later this was true in LaGrange as well.38 These enterprises, however, did not emerge fully grown. Early ventures into the local economy are very hard to document other than by word-of-mouth, but the corporate memory is one of early movements into a wider economy in LaGrange in the 1960s and 1970s. It is impossible to document how much of their economy depended on these enterprises.

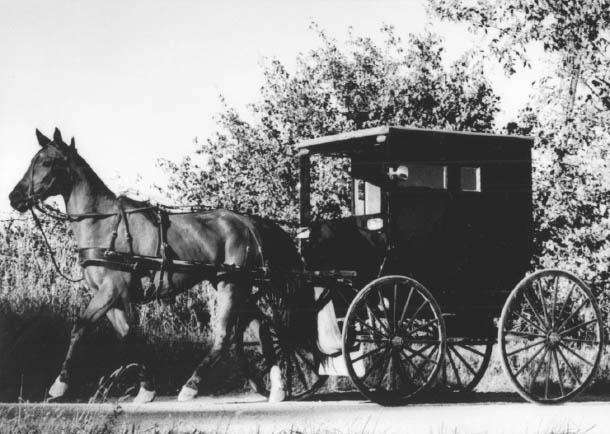

Amish Buggy. Photograph courtesy the South Bend Tribune.

Amish teenagers had long worked outside their own homes, especially those trying to raise money to purchase their own farms. LaGrange is a small, rural area, and opportunities have always been limited. People in LaGrange, however, remember Amish youth working in restaurants or in small businesses, where they picked up some business practices and financial acumen. Amish youth began working in a Mennonite-owned recreational vehicle factory in Elkhart in the early 1960s. Since the business was owned by Mennonites, the Amish community was willing to try this avenue of employment, despite a certain amount of trepidation.39 At the factory, the young men could wear their own clothes, could work in an environment they understood (carpentry), and would have a workday calendar geared toward their culture. The reputation of these workers spread, and soon other local manufacturers courted workers from the community. To employ the Amish, company representatives were required to meet with local bishops and ensure them that their factory was a safe haven for these young men. Eventually some of the factories began to send small buses to pick up their workers and take them home again at night. Other factories installed buggy stands in their parking lots.

Within this new environment, the Amish struggled to maintain an order they knew and understood. In the beginning most only worked until they had the money to purchase a farm or to marry, but some eventually found factory work compelling. They were good at it, and it paid well. Historians have argued that this newfound wealth and capitalist impulse created a fundamental shift in Amish culture: New social strata arose, childrearing practices changed when one or both parents were frequently gone, gender roles were pressured, and entrepreneurs began to rationalize the use of forbidden technology.40 Yet sociologist Thomas J. Meyers saw the growth of factory work as another facet of the carefully negotiated and delicately maintained Amish boundaries; his examination of the LaGrange and Elkhart move to the factory concluded with a cautious, yet optimistic, view.41

Whatever the long-term effects, these forays into a new market economy began in the first few decades after World War II. Just as with telephones, tractors, and automobiles, the Amish in LaGrange had the luxury of observing the struggles of other Amish settlements and picking and choosing whether or not to accommodate these new opportunities. Just as before, church districts in close proximity disagreed. Yet the safety valves of the past continued to function, and for the most part the area remained firmly Old Order.42

Schism, however, did not negate cooperation in times of severe need. In 1965 the area of Elkhart and LaGrange Counties experienced a devastating tornado. Although the damage was extensive and loss of life stunning, the Amish fared better than most; they attributed this to the fact that they watched the skies rather than listening to the radio for weather forecasting.43 The death toll did not include any Amish, and the damage to houses and farms, although extensive, was quickly repaired, because Amish from across the country arrived to help raise barns, rebuild homes, and plant fields. One Amish writer noted that since the Amish did not depend on commercial insurance, rebuilding could and did begin at once.44

There were, however, two government programs that the LaGrange Amish did not have a chance to evaluate before they had to react: Social Security and Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) regulations. The Amish objected to the Social Security system from the start. Relying on the government would undermine community and family responsibility toward their members when in need. When the government extended the program to include even self-employed people in 1956, the Amish directly confronted governmental regulations. At first the Amish offered passive resistance. They tried to simply ignore the law or even close bank accounts, but the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) has never allowed citizens to ignore their tax obligations.45

In 1958 the IRS began to seize and sell farm animals to recover the lost Social Security tax.46 One of the most famous cases of this was Valentine Byler, a farmer in New Wilmington, Pennsylvania. In 1961 IRS agents marched onto Byler’s field, unhitched and confiscated his plow horses, and then sold them to recoup Byler’s unpaid Social Security taxes. When they sold for more than was owed, the IRS returned the difference to Byler. Just as with the Iowa school disaster later in the decade, this event catapulted onto the front pages of newspapers across the country and garnered sympathy for the Amish.47

Like Byler, LaGrange farmers also faced difficulties with the IRS. The extent of the problem is unknown, but on 30 October 1958 the Budget told of Amish repurchasing at auction the very horses seized by the government for nonpayment of Social Security taxes.48 By 1960 Amish representatives, eschewing trials, opted for lobbying Congress. Five years earlier a bill had been presented to exempt Amish and others with religious objections to participation in Social Security. Amish representatives from Pennsylvania continued to lobby Congress through the late 1950s, but there was not a concerted effort on the part of several districts until 1960.49 The Byler case the following year simply made it easier to get an audience. By 1962 the effort was organized in the vein of Noah’s Ark; lobbyists visited each congressional office two by two. The effort brought a bill to the Senate, which was passed there but could not even reach the floor in the House. The official government position remained that Social Security could be mandatory and still workable. After all, what would happen to those people who left the Amish later in life, never having paid into the system?50

The Social Security exemption for the Amish finally passed in 1965, but it only excused self-employed workers who had a religious objection to participation. These objectors had to prove that they were members of a recognized historic peace church that had been in existence continually since 1950. Each worker had to file individually to claim this exemption and waive all future benefits. The Budget of 11 August 1966 explained the procedure to the Amish, admonishing them to carefully fill out the forms to avoid duplication in the issuing of exemption numbers.51

Problems with OSHA regulations came a bit later, but by then Congress was familiar with the Old Order Amish. OSHA regulations of 1978 exempted both the Old Order Amish and Sikhs from having to wear hard hats.52 Most of the problems with hard hats surfaced in other states, but there are local statements concerning a growing difficulty over safety regulations with the recreational vehicle industry in Elkhart. The 1978 regulation relieved the problem, which had never exploded. Likewise, difficulties over the state regulation requiring Amish buggies to carry reflective hazard emblems appeared to have only sporadic episodes of civil disobedience.53

With the advent of the Cold War, only months after the release of the last Civilian Public Service participant, President Harry S Truman proposed a return to the draft. Whether by plan or simple oversight, religious conscientious objectors received automatic deferments. As would be expected, however, the law changed at the height of the Korean War to mandate their service.

Evaluating the CPS program in World War II as a success, the government reinstituted the hospital service portion of the program. Although there were other service possibilities, nearly all I-Ws, as they were called, held hospital jobs in 1954. The more vocal of the historic peace churches thought this a good program at first, but there were difficulties, including the lack of connection to a nonresistant community. This was especially threatening to the Amish, who feared the lack of connectedness, individual autonomy, and the lure of the big city.54

These fears appeared justified as more Amish men found themselves tempted by materialism, attracted to non-Amish women, and lured away from home and their faith. Even those who remained Amish found their memories of the temptations disturbing. William Henry Yoder, an Old Order Amish man from Shipshewana, served in a community hospital in Wooster, Ohio, in 1956. He readily admitted that he “was not proud of some things [he did] in those two years. . . . There were many temptations.” In his estimation, one of the largest problems was working in an environment with women. Some men married non-Amish women whom they met in the hospitals.55 Apparently those who were married and took their wives with them had a better chance of surviving within the Amish faith.56

Unlike the circumstances of World War II, the men were paid, worked forty-hour weeks, rented apartments, and built friendships with both men and women. They experienced city living, electrical appliances, travel by car, television, and extra money in their pockets.57 Since the men were widely dispersed, support groups were few and of a makeshift nature.58 Their naïveté sometimes led them into threatening situations: One Amish man, accepting a ride from a stranger, was subsequently propositioned. Terrified, he negotiated his own release and return to the bus station by promising not to report the stranger to the police. With great relief the man wrote, “Prayers of home folks and ministers were answered that night concerning [God’s] protecting hand.”59

As these accounts reached home, the community reacted. A number of Amish youths refused their assignments to hospitals in cities, and in 1955 three received courts-martial for their intransigence. They were convicted, sentenced to five years in prison, and fined two thousand dollars. In a haunting replay of the World War I experiences, the Amish refused to wear prison uniforms. The warden took away their food until they were compliant. When the Amish remained uncooperative and went on what was essentially a hunger strike, the warden found a suitable compromise.60 The numbers of these complete resisters remained low, but there were enough problems that by 1960 the need for a meeting seemed evident.

On 23 September 1960, approximately one thousand Amish met at the farm of Levi Yoder, an Old Order Amish man who lived near Shipshewana. John Lapp, a member of the Mennonite I-W Coordinating Board, and John D. Troyer, the local Old Order bishop, arranged the gathering. Lapp arrived a half-hour before the scheduled seven o’clock meeting to find a number of horses and buggies, and even a few automobiles, already assembled. People came from Nappanee, Goshen, Allen County, and as far away as Arthur, Illinois. After a brief devotional, members of the Coordinating Board gave a history of the I-W program and explained the results of the evaluation of the program conducted the previous spring. One of its members, Paul Gross, had visited several of the hospitals in Indiana; he recommended some as appropriate for service. The meeting then turned to the central issue: the dangers represented by participating in the program and possible solutions.61

Lapp suggested that the local community needed to do more to prepare the men before they left for I-W duties. He said that if the young men failed, it was not their failure but rather the failure of their parents to properly prepare them. He also suggested an orientation program for the men before they left, which would include warnings of dangers and temptations, some explanation of hospital work, training in how to use the Bible, and grounding in peace issues. From a practical standpoint, Lapp recommended Amish representation on the Coordinating Board, Amish placement counselors, and planned ministerial visits to the I-W participants. The group then followed with a demonstration of an “FBI investigation” (questioning session).62

These adaptive remedies were surprisingly inappropriate for the Amish. They were practical for Mennonites, but not for a culture that eschewed individual agency and permanent connection with outsiders. Yet for the moment, having nothing better to offer, the Amish acquiesced and continued within the I-W program, while trying to make slight adjustments. In 1966 an Amish woman from Ohio helped create and organize a periodical, the Ambassador of Peace, for the conscientious objector. The magazine was designed to create a connection with the people back home and certainly helped to support conscientious objectors during their time of service. Yet a periodical alone could not solve the problems posed by the I-W program.63

That same year Amish bishops met at the Graber schoolhouse in Allen County, as documented in the beginning of this chapter. This meeting was strictly Old Order Amish and did not include representatives from any other Anabaptist or historic peace churches. The bishops planned a delegation to travel to Washington, D.C., to find out if something could be done about the I-W program.64

On 16 November 1966 eighteen Amish bishops met with Harold Sherk, then executive director of the National Service Board for Religious Objectors. Of particular concern was the new draft law, the old one having expired in June 1966. According to the meeting minutes, “the Bishops explained that the present hospital plan is not proving satisfactory for many of our boys as there is too big a percent not returning to the Amish Church.” Sherk suggested that the Amish develop their own alternative, such as “forestry or reclaiming of land,” and they agreed to meet again to review the proposed alternative.65

That night fourteen of the eighteen bishops met at the hotel in which they were staying. After a lengthy discussion, they proposed that “there should be a committee to represent the Old Order Amish from all states as a group to Washington in matters that concern or hinder our Old Order way of life, to counsel with the various groups or states and see if a unified plan could be found that would be acceptable to Amish as well as Washington.” They elected three in their midst to start the committee and recommended that each Amish district elect a representative to serve on it.66

On 2 December 1966, at a meeting held halfway between the major settlements in Pennsylvania and Indiana, the bishops read, discussed, and eventually approved an alternative service plan for Amish in I-W, which would consist of agricultural deferment on the farm or somewhere else in their community. Perhaps more important than the proposal itself, the committee was moving into uncharted territory by creating a structure independent from any other peace church. The bishops named it the Old Order Amish Steering Committee and specifically stated that following the Mennonites too closely was “undermining our Amish way of life.”67

Afterward, “over 100 bishops from various states and communities” met on a farm in Holmes County, Ohio, to discuss the I-W proposal and evaluate the Amish Steering Committee. The minutes of this meeting were extremely brief, but they reported that those in attendance considered whether they “could work as a group” and concluded, “This proved to be a very serious meeting with full approval and many encouraging words.”68

A series of meetings followed over the next year between the Amish Steering Committee and the National Service Board for Religious Objectors and between the Steering Committee and the respective church districts. Eventually all parties involved were able to agree on a mechanism for I-W service using Amish farms. When an Amish farmer hired a conscientious objector, he relinquished the legal rights to his farm to the Steering Committee for the length of the conscientious objector’s service. The conscientious objector was then paid from the proceeds from the farm.69 During this same period Mennonites began shifting from a passivist to an activist stance over peace issues.70 In contrast, the Amish continued to see military deferment as a precious privilege. They fought hard to present this attitude to the Selective Service Board and cautioned their members to remain humble, not boast about deferment, and in particular be sensitive toward their non-Amish neighbors.71

The draft had pushed the Amish into creating a committee that for the first time was in a position to represent all the Amish on several fronts. In its early stages the committee concentrated only on the draft issue and was extremely careful to portray itself as representing, but not speaking for, the Amish. Yet in October 1971 the minutes of the committee’s fifth annual meeting noted a growing realization that it offered an acceptable alternative to handling difficulties, rather than resorting to less Amish ways like the courts: “It was not the custom of our forefathers to take issues to court. Would it not be more scriptural to, in a united way, stand up for our religion even if it would bring prosecution. . . . If we work in a sincere, peaceful and united way then in faith we will receive the blessing if we are worthy and if not let us take it for a worning [sic] and for our betterment.”72

Although many recognized the potential for good in this new group, increasing reliance on the Amish Steering Committee provoked concern. In response, the committee produced a governance statement defining the limits of power: “[W]e will need a good set of rules and guidelines as the church needs rules or a ordnung [sic].”73 The statement began by outlining the growing need for committee involvement in areas beyond Selective Service: specifically, concerns over parochial schools and Social Security that both predated the committee.74 The minutes acknowledged, “[S]ome people may think that the Committee is trying to run the churches but this should not be so. The Committee is only the voice of the Churches combined and the Churches are the backbone.”75 After listing the procedures for incorporating new members and redefining the role of the committee, the minutes again emphasize that the committee “should not commit itself further to the officials then [sic] what they can reasonably feel sure that the Churches will back them up as they are only the voice of the church.”76 The rules went further to state, “Let no group however feel that differences of home rule or ordnung [sic] may enter in as no Committee man or State Director shall infringe upon or dispute or consul [sic] differences of ordnung [sic] or home rule from the various communities.”77 In conclusion, they reminded everyone of the seriousness of the responsibility, that decisions made by the Steering Committee affected not only those present but generations to come.78

At first glance, this change in the internal structure of the Amish culture is stunning. As discussed in the introduction, the Amish are a congregationally structured church without an overarching hierarchy. As early as the end of World War I, the Amish hoped just to be left alone, but outside incursions continued to come, whether by the government, the military, or their non-Amish neighbors. If these incursions were left unchecked, the Amish culture was at risk. During the years following World War II, Amish across the country relied heavily on Mennonite help and protection. When Mennonite goals began to diverge from their own, the Old Order Amish realized that they needed to create some way to retain control of their own lives.

Fully understanding that the Amish Steering Committee posed threats to old ways, the Amish tried to create an organized approach to check the threats to individual church districts. Through the traditional use of a mechanism similar to the Ordnung, the Amish have managed to limit the inevitable reverberations of the Steering Committee. The committee is supposed to function as a gatekeeper by negotiating threats from outsiders; it has allowed the Amish to be in control of this function themselves rather than leaving it in the hands of others, no matter how well-meaning they might be. To that extent, the Steering Committee has been worth the inevitable risks.

Those who study the Amish have carefully expressed concern over the long-term effects of the Steering Committee. The typical word choice to describe the committee tends to be “paradoxical,” which, indeed, it is. There is a fine line between speaking as the “voice” of the church and controlling that voice.79 At present it is impossible to define the short- and long-term consequences of the committee for the Amish. Certainly there are and will be consequences within Old Order Society, but it is also certain that they really had no choice. The emphasis through the committee remains on community rather than individual action. If this intent remains reality, then the benefits should outweigh the difficulties. The final word on the issue belongs to the members of the Steering Committee itself:

The Committee nor its Directors shall work as a mission group but shall work to uphold the principles, religion and customs of the Old Order Amish as they were handed down to us and in a way that the Oldest of the Old Order can cooperate and benefit as much as possible. Let us remember that it takes the support of all old order Amish communities and Directors and districts to make a strong chain and that a chain can be no stronger, regardless of how heavy, than its weakest link. Let us avoid any weak links and most and above all operate and co-operate in a way that the sega [blessing] can be with us and let us work together and stand up for our religion in a way that the world can respect us and see the light shine and not be disappointed.80