Organisations regularly fail to take into consideration that their culture must be aligned to their business strategy. This may seem obvious as even simply reading the words ‘align to the company strategy’ immediately awakens our awareness to the importance of this point.

The relationship between culture and strategy

Occasionally I find myself working with a leadership team that, despite its combined efforts, still struggles to grasp the link between culture and strategy. This usually occurs because the leaders have little or no ability to see the wheelbarrow. There comes a point where there is no point continuing to describe the attributes and influence of culture if people do not have any direct experience of culture. In other words, discussing something they have no experience of often reinforces any existing cynicism or scepticism already existing in the minds of the leaders.

In these situations I find it useful to switch from discussing the direct link between the culture and strategy, as the leaders cannot see the connection, and instead use a simple metaphor that captures the mutually dependent relationship between the two. Over years of consulting on culture to organisations, I have tried numerous metaphors to help people to make the link between culture and strategy. The most effective metaphor is one I invented which I refer to as the opposable thumb of culture. As we all know, an opposable thumb allows the digit fingers to grasp and handle objects. It is this ability to grasp objects in this manner that is a distinguishing characteristic of all primates, including, of course, humans. If we imagine that our index finger represents the organisation’s strategy, and our thumb is the equivalent of the company culture, we can begin to explore the relationship between the two in a very simple and practical manner. The index finger (strategy) points the way (see figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1 the index finger points the way

The index finger, representing strategy and the business-operation model, isolates a specific and desirable outcome or destination for the organisation. In doing so, the index finger symbolically represents the separation of one objective from the many optional goals an organisation could choose from. The thumb in this metaphor represents culture and the position of the thumb indicates whether the culture will provide its approval and willingness — thumbs up — to align to the strategic direction and outcome, or not — thumbs down (see figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2 thumbs up when culture aligns to strategy, thumbs down when it doesn’t

Interestingly, the thumb is the only digit on the hand that has two phalanges (bone hinges or knuckles) rather than the three found on the fingers. The two hinges can be thought of as representing either for or against. When they are for, we get a cultural thumbs up regarding the strategy, and the culture’s full capability can be brought to connect with the strategy.

When the culture approves of the chosen strategy, then, and only then, can the opposable thumb (the culture) be drawn upon to close with the index finger (strategy) and grasp the opportunity to generate results (see figure 3.3). Typically, even the most evasive manager or leader finds the opposable thumb metaphor an undeniably useful means for them to grasp the connection between culture and strategy and, more importantly, use it to explain the connection to others. It is important to ensure leaders are provided with every opportunity to enable them to see the wheelbarrow. For, as we shall see in the next chapter, although leaders do not own the organisation’s culture, they do have a significant influence in terms of inspiring the culture to engage with the business in a positive and supportive relationship. The more leaders can see the power and influence of culture in shaping the organisation’s performance, the more likely they will be to put the time and effort into influencing culture to align with strategy. If you have leaders in your organisation who do not understand culture or still perceive it as a soft topic, one that is best delegated to the human resource team, I strongly recommend you take the time to support them to begin to see the wheelbarrow and its ongoing and indispensable role in driving business performance. An unrecognised or ignored wheelbarrow can, as demonstrated in the Soviet factory story I shared earlier, have a real and potentially costly impact on business performance.

Figure 3.3 thumb pinched with finger creates a grasp ability

Culture and performance

At this point it might be useful to pose a question for you to consider. If you look at your organisation’s current business strategy and performance, and consider this in relation to the ideal performance and results you want or need your organisation to achieve, does culture play in supporting you on this journey? Does your workplace culture have a significant role? A minor role? A moderately important role?

If you are not sure, it might be worth your while considering what you are trying to achieve strategically and then come back to the question, ‘How important is our workplace culture in supporting our business to deliver on its strategic objectives?’ This is an important question to consider for a number of reasons, including the following:

- The question enables you to determine why your organisation should, or should not, invest time, money, energy and effort to improve your culture. If culture has no value-contribution to make in terms of delivering a better performance or attracting good people to join your organisation to increase performance and deliver better results, then there is no need to begin culture work.

- Posing this question to your senior leadership or employees, or both, can highlight the varying perspectives held by people across your organisation as to the relative value they perceive culture can contribute to the organisation’s performance and results. This can lead to important dialogue that can help you take into consideration perspectives that might otherwise have been overlooked regarding the role of culture.

- Posing this question will often highlight the extent to which people in your organisation even understand or are aware of what results are being, or need to be, generated.

- Finally, this question can also highlight how informed or aware people are of the role of culture in a business.

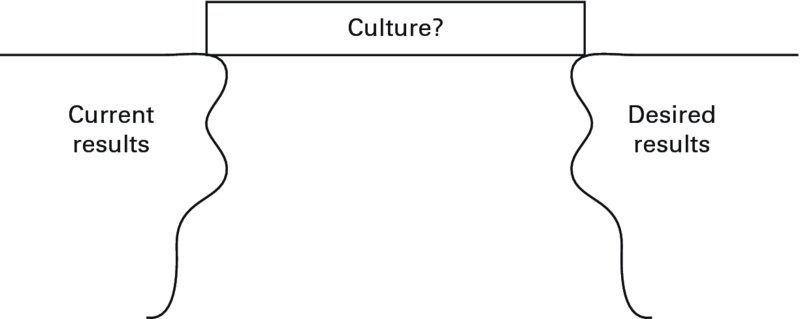

All four of these opportunities can provide useful insights to better inform your organisation of how to tap into further opportunities for growth and development. These are important discussions to have, as the relationship between culture and strategy is far more influential than most businesspeople give credit to. In simple terms the key question to consider can be summarised in figure 3.4: ‘Does culture play a role in supporting our results to move from where they currently are to where we would prefer them to be?’

Figure 3.4 does culture play a role in supporting your results to move from where they currently are to where you would prefer them to be?

Having considered the relationship between culture and strategy, the next step is to understand how to go about aligning the two. A number of considerations have to be taken into account here. The first of which, and the focus of the next section, is to understand the importance of culture and strategy in terms of the organisation’s operating models. Later in the book, we will explore other considerations such as the power of your culture, leadership, purpose and other factors.

Aligning culture and company strategy

Organisations repeatedly work on their cultures and fail to take into consideration the importance of aligning culture and strategy in creating a successful company culture. We have already discussed posing the question ‘To what extent does culture play a role in supporting our organisation to move from where we are to where we want to be — from achieving our current results to achieving better results?’

Although you might readily arrive at the conclusion that your culture has a major or minor role to play in supporting you achieving your desired business results, many leaders struggle to understand or articulate anything beyond a few simple adjectives to support their argument. I have heard many leaders say things like: ‘Yes we need a positive, energised culture to deliver the strategy’ or ‘A creative, driven culture is crucial to our success’. These two descriptions are too vague to be of any use in terms of isolating a culture that can add value to your business. Really aligning your organisation’s culture to your business strategy requires you to first have absolute clarity and agreement on the strategy itself. A simple test of this is to ask your leadership team next time they gather to quickly write out a description of the current business strategy. When everyone has done so, ask them to each read out their description one by one and listen for the degree of unity the descriptions highlight. If they are aligned, great. If not? This book can help you explore how to become more aligned on your view of the culture.

Misaligned on strategy

Whenever I discover I am working with a senior leadership team that is unaligned or even confused or at odds regarding the organisation’s strategy, I go back to a tried and tested strategic model that I was first introduced to when I was researching my book Leading Through Values: Linking Company Culture to Business Strategy. I was discussing with a client how we might link their culture more closely to their chosen strategy. To explain their chosen strategy the client referred me to the work of US business consultants Fred Wiersema and Michael Treacy, as captured in their best-selling book, The Discipline of Market Leaders: Choose Your Customers, Narrow Your Focus, Dominate Your Market. The book outlines some fundamental truths about the modern marketplace and customer behaviours, and how organisations can best respond to their customers’ differing needs in regards to their perceptions of value. Because not every customer in the market is the same, different customers are looking for different kinds of value. As US President Abraham Lincoln said: ‘You can please some of the people some of the time.’ Organisations need to develop strategies to ensure they can please some of the customers all of the time. Meaning any given company can never expect to have all of the customers within a given market. However, they can work towards pleasing some of those customers repeatedly. The authors suggest that the key to success lies in narrowing the company’s focus on just one key element of value. Because trying to cover all aspects of value often ends up with contradictory results. Let me explain.

Customers tend to fall into three groups, categorised by the value element they are most attracted by. The three categories of value that most businesses can tap into in order to provide for their customers are:

- Best product. In this case, customers are aware of the price of your competitors’ products, but are prepared to pay a premium for cutting edge design, performance and features. For example, Apple would fit into this value offering category. There are other products available at cheaper prices, but Apple’s products are so elegant and easy to use that they don’t even need instruction manuals.

- Best service. This relates to customers who prefer to have their individual requirements understood and met through an ongoing relationship with your company. Your local family restaurant would fall into this category. Over a period of visits the waiters, chefs or owners will come to know your tastes in food and wine along with your preferred seating.

- Best price. Customers who are just interested in the lowest-price reliable products that come with no-hassle delivery favour organisations delivering into this category.

Most organisations offer a mixture of all three of these value categories. They will, for example, have a product at a set price and serve customers who want to purchase the product. However, what Wiersema and Treacy are suggesting is that to excel, and in fact lead, your market in any one of these categories requires your organisation to have the discipline to choose and focus on just one of them. To try to deliver on all three becomes counterproductive, for several reasons. First, the levels of value are constantly rising. Prices become cheaper; products improve; customer service standards lift. To excel and compete on all three fronts is too demanding, especially as customer expectations in relation to all three categories are constantly rising, too. An organisation can only stay ahead of the competition if it consistently delivers more added value. Second, to invest in product development costs money, which, when invested, is a cost that at some stage will have to be covered within the pricing of the product. Aiming for top products, therefore, contradicts the cost-saving business discipline required of a price-centred value category. Likewise offering a high level of customer service requires higher skill levels, the cost of which also needs to be covered in the price, again contradicting the cost-saving business model. Each value category your organisation chooses to take on as its competitive advantage to differentiate itself in the marketplace requires a dedicated and disciplined focus and must be placed ahead of the other two disciplines in terms of investment decisions, structure and relevant culture.

Price, service or product? Pick one!

Many of my clients’ leadership teams struggle to determine which of these three disciplines is or should be their priority. Many cannot even cope with the idea of prioritising one over the other two. The habit of thinking in traditional business is heavily dependent on the ability to think in strictly binary terms. Yes or no. Profitable or unprofitable. Invest or not. Retain or sack people. Buy or sell, and so on. When asked to rank the three optional value propositions, it is as if their minds cannot grasp the idea and they regularly protest, ‘But they are all important.’

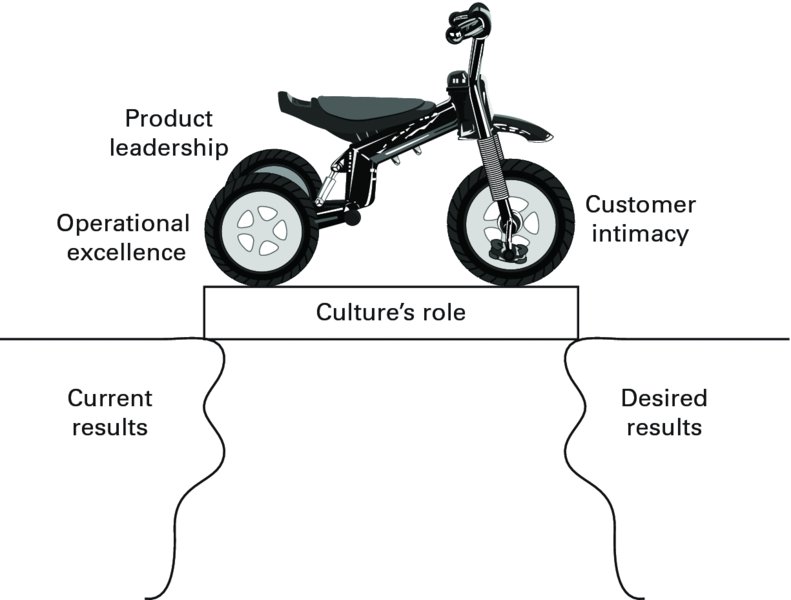

To help leaders come to grips with this idea, I have devised a simple yet effective model. I ask leaders to consider the three strategic disciplines as being represented by the three wheels of a tricycle (see figure 3.5). The front wheel of your tricycle? As we all know, the front wheel is the largest and is the wheel that is connected to the handlebars and, therefore, the steering column. So the primary value discipline can be considered to be the tricycle’s front wheel. As it is the largest, we also want the majority of people in the organisation to dedicate their focus and energy to it. It also, as the front wheel guides the very direction of the organisation as a whole, ensures that all decisions made within the organisation contribute in some way to ensuring the front wheel’s direction is maintained.

Figure 3.5 the tricycle model

The benefit of using the tricycle model is that even those leaders from departments associated with one of the back two wheels instantly recognise that, without their contribution, the front wheel could not be projected forward to achieve its objective of delivering value to the customer. The smaller, back two wheels are seen by all as both the stabilisers for performance and the supporting energy drive.

The ability to deliver sustained value to customers requires this understanding of a separate yet ultimately supportive mixture of disciplines, with one chosen as the front runner or front wheel.

From customer value to operating model

Having chosen its front wheel of customer-adding value, the organisation must then align its operating model with this objective in a variety of ways. The organisation’s operating model will be a mixture of the structure, management system, operating systems, finance model and culture, which are all focused on delivering customer value. Each of the value categories of price, service and product requires a different operating model. Again, Wiersema and Treacy’s research insists that, in order to deliver outstanding levels of value in one area, organisations must commit to one of the following operating models. Failure to do so leads to split attention and focus and contradictory operational functions and objectives leading to mediocre performance and customer experiences.

The following discussion provides brief outlines of these operating models and I strongly recommend you read Wiersema and Treacy’s book, The Discipline of Market Leaders.

Customer intimacy

Organisations that deliver value through customer intimacy are committed to building long and deep relationships with their customers. In this model, the organisation’s focus is to always deliver exactly what the individual customer wants. Think of a waitress at a breakfast asking you how you would like your eggs, and no matter what you say, the waitress will instruct the chef to deliver exactly that. You know you have walked into an organisation that doesn’t do customer intimacy when you ask for a boiled egg and the waitress tells you they only do poached or scrambled. Responding to such individual customer needs is called ‘tailoring’ in Wiersema and Treacy’s book. The main features of this type of organisational operating model are:

- a company culture that encourages always going the extra mile for clients

- business systems that focus on and reward a small number of select clients

- an organisation that ensures all service offerings encourage a long-term relationship with the client

- a company that empowers employees (within reason) to make any decisions on the spot that will delight the customer.

Operational excellence

An organisation attempting to deliver the mix of value offered through quality, price and ease of purchase better than anyone else will focus on operational excellence, in other words, execution. The main features of this type of organisational operating model are:

- streamlined processes standardised to minimise costs and problems

- usually a low tolerance for mistakes: failure is not an option

- tight control of all procedures and logistics: significant decisions are made by leadership and management, never staff

- management systems focused on efficiency and consistency

- a company culture that rewards efficiency and consistency.

Product leadership

An organisation committed to excelling at adding value through their products will continually add new features and benefits to the products or update the product with a 2.0 offering. Being the first to launch a new product range is another key focus of this operating model. The main features of this type of organisational operating model are:

- a company culture that encourages ideation and the ongoing advancement of counterintuitive or evolutionary thinking

- failure is an option as it is seen as a learning experience; however, failing fast and early is preferred

- invention and innovation are ongoing — research and development budgets in these organisations are always substantial

- less reliance on functional roles and more on a matrix model or project teams that dissolve when the project’s objectives are achieved.

Having considered the three customer value options and their correlating operational models, let’s just pause for a moment and review what we have learnt so far. Figure 3.6 highlights the key components.

Figure 3.6 does culture influence your strategy?

We have now added to the original concept of an organisation determining what results are desired for the future, and to what extent the company culture will play a role in advancing towards these objectives, by adding the idea that one of the three strategies and supportive operating models should be chosen in order to ensure maximum alignment of the organisation’s processes and systems.

Just clarifying this one strategic discipline alone can significantly enhance an organisation’s ability to perform and transition from its current results to its desired results. In other words we can now see we are deliberately moving from the current results to the desired results by disciplining our decisions, investments and activities through our chosen front-wheel operating model to achieve our desired results, delivered through achieving everything we possibly can relating to our chosen customer value proposition.

Values alignment to strategy

As we saw in each of the three brief explorations of the operating models, culture has a role to play in supporting the delivery of every customer value proposition. We will now go one step further and identify the cultural values groups that enable an organisational culture to best align to support the delivery of the customer value proposition. To support your understanding of how a culture can possibly influence an organisation’s operating model we must first understand a little more about culture. Author and professor of management emeritus at MIT Sloan School of Management Edgar Schein, in his book The Corporate Culture Survival Guide, provides a beautiful, simple and, in my experience, accurate model for understanding how cultures form and operate.

Schein suggests there are three distinct layers to culture worth considering. On the first, or surface, level culture consists of the observable and audible elements, such as:

- artefacts

- icons

- people’s behaviours

- furnishing

- language and conversations

- jingles, music, anthems

- symbols and icons.

The second layer of culture consists of the underlying and unseen motivational aspects known as the layer of human values. The third and deepest layer relates to the underlying assumptions and transparent belief systems, often referred to as the unwritten ground rules of a culture.

The second layer of values in this three-tier conception of culture is an area I have specialised in for many years.

I used a comprehensive values inventory, administered and developed by Paul Chippendale, of the Minessence Values Education Centre, which includes the 128 known human values. I worked with Paul to identify three groups of values that I suspected each of the three operating models would be reliant upon if they wanted to have the people delivering, overseeing and managing the systems to stay focused and diligently dedicated to the systems. If you are interested in the somewhat logical leap that led to the consideration that the 128 human values might relate to the delivery of the three strategic disciplines of operational excellence, product leadership and customer intimacy, you might refer to the book I wrote with my practice partners on the subject called Leading Through Values.

The work Paul and I undertook led to the discovery that the 128 human values fall into three distinct categories. First, we identified a group of values that were to do with having a motivation to experience control in life. The second group were values to do with people’s motivation for relating to other people. The last group was a set of values that motivated people to grow and develop themselves or the systems and processes humans use to engage in the world. Not surprisingly, we named these three categories of values control, relating and development. Since discovering these three sets of values I have reviewed all my work and field notes as an anthropologist and also observed that at every organisation I come into contact with (as a consultant or as a customer), I have consistently found these three groups of values to be present in all cultures. A simple and useful exercise you can conduct is next time you are at work, pay attention to what people are doing and then consider what are the underlying motivations for the action, behaviour or conversation you are witnessing. I suspect you will that find all human activity you witness will be an attempt to control something, relate to somebody or develop a pathway, insight, knowledge, solution or answer.

I have provided a sample of some of the 128 values from each group here to help you gain a sense of the type of values that motivate people in terms of controlling, relating and developing. If you are not that interested in the specific values just jump ahead a few pages to the continuing dialogue. The following are the sample human values in the three categories.

1. The relational values examples: relating

- Accountability/ethics — to hold yourself and others accountable to a code of ethics derived from your values. To address the appropriateness of your behaviour in relation to your values.

- Accountability/rule — to be held accountable to established rules, codes of conduct, procedures, standards, and so on.

- Collaboration — to work cooperatively with a common purpose, sharing responsibility and accountability.

- Communal discernment — to elicit communal wisdom in order to determine appropriate actions through careful reflection, and honest, open dialogue.

- Congruence — to align one’s words, actions and deeds with espoused beliefs. (Walk the talk. Practice what you preach.)

- Empathy — to deeply relate with others in such a way that they feel understood.

- Family/belonging — to have a place or sense of home; to be devoted to people you consider family and to experience belonging and acceptance.

- Generosity — to unconditionally share your resources, talents and skills as a way of serving others.

- Hospitality/courtesy — to treat others, and be treated by them, in a polite, respectful, friendly and hospitable manner.

- Human dignity — to observe the basic right of every human being to have respect and to have their basic needs met in a way that will allow them the opportunity to develop their potential.

- Loyalty — to strictly observe promises and duties to those in authority and to those in close personal relationships.

- Presence/being — to be there for another person in such a way that increases their self-knowledge and awareness.

- Sharing/listening/trust — to actively and accurately hear and sense another’s thoughts and feelings. To express your own thoughts and feelings in a climate of mutual trust.

2. The control values examples: controlling

- Administration/control — to exercise administrative and/or management functions and tasks.

- Communication/information — to ensure the effective and efficient flow of ideas and factual information.

- Control/order/discipline — to maintain control and order through rules and discipline.

- Duty — to follow customs, regulations and institutional codes out of a sense of duty.

- Efficiency/planning — to plan systems and activities that will maximise the use of available resources.

- Financial security — to accumulate financial wealth in order to be secure.

- Financial success — to achieve financial success through the effective and efficient control and management of resources.

- Hierarchy/protocol — to have a methodical arrangement of persons and things, ranked above one another, in conformity with established standards of what is good and proper within an organisation.

- Law/rule — to live life by the rules — to govern your conduct, action and procedures by the established legal system.

- Management — to control and direct people in order to achieve optimal productivity and efficiency.

- Membership/organisation — to take pride in belonging to and having a role in any form of organisation.

- Obedience — dutiful compliance with moral and legal obligations established by authorities.

- Productivity — to be energised by generating and completing tasks and activities, and be keen to meet or exceed set goals and expectations.

- Rationality — to think formally, logically and analytically, preferring reason to emotion.

- Unity/control — establishing and maintaining efficiency, order, loyalty and conformity to established norms.

- Work — to have the skills, confidence and desire to engage in productive work.

3. Development values examples: developing

- Achievement — to accomplish something noteworthy and admirable in your work, education or your life in general.

- Adaptability/flexibility — to be flexible and adaptable in response to changing circumstances.

- Construction/new order — to initiate and develop a new form of organisation.

- Convivial technology — to apply technology for the benefit of humanity and the planet.

- Creative ideation — to transform ideas and images into concrete form.

- Decision/initiation — to take personal responsibility for setting direction and initiating action.

- Discovery and insight — to be motivated by moments of discovery and insight.

- Education/knowledge — to engage in ongoing learning to gain new facts, principles and insights.

- Faith/risk/vision — to commit to a venture, or cause, even if it means personal risk.

- Fantasy/play — to seek personal worth through unrestrained imagination and personal amusement.

- Human rights — to create the means for every person in the world to experience their basic right to life-giving resources, such as food, habitat, employment, health and a minimal practical education.

- Independence — to be free to think and act for yourself, unrestricted by external constraint.

- Leadership/new order — leading/developing a new organisation or transforming an existing one.

- Minessence — to miniaturise and simplify complex ideas or technology into concrete and practical applications for the purpose of creatively enhancing society.

- Organisational growth — to creatively enable an organisation to change and grow.

- Organisational mission — to define and pursue an organisation’s mission.

- Pioneerism/progress — to pioneer new ideas (including technology) for societal change and providing the framework for realising them.

- Research/original knowledge — to systematically investigate and contemplate truths and principles that lie behind our experience of reality to create and communicate original insights.

These three values sets provide the underlying motivation and meaning of a culture. Cultures usually combine all three values sets in their view of the world. However, because of the surrounding context in which a culture finds itself, usually one of these sets of values tends to dominate the other two. This occurs for two reasons. First, because one of the values sets has more values that are shared by people. The second reason can be that the shared values from one particular set are also held as being of more importance or of higher priority than values from other sets.

Cultures with an emphasis on the control values tend to do better at aligning and executing with the operational excellence operating model. Cultures with a emphasis on the relational values tend to do better at aligning and executing with the customer intimacy operating model. Cultures with an emphasis on the development values tend to do better at aligning and executing with the product leadership operating model. This makes sense, as all the things that need to be attended to in each of these distinct operating models require a different set of motivating and directional influences. In other words, they are dependent on a unique set of aligned values to guide people’s behaviours, actions and decisions. Because these values are organic and therefore naturally embodied in the culture, the effort required to deliver on the values is minimal, because the effort will always feel natural to the people in this culture. It is their preferred way of operating. Their own personal values demand and guide them to behave in a way that fits perfectly into the operating model, which in turn feeds into the delivery of the customer value proposition. We can see the relationship of this natural fit in table 3.1.

Table 3.1 the relationship between values and operating models

| Values set | Operating model | Customer value |

| Control | Operational excellence | Price |

| Relating | Customer intimacy | Service |

| Developing | Product leadership | Product |

As you might expect, whenever I have come across a culture whose values preference is misaligned with their intended operating model and therefore their delivery of the desired customer value, the organisation’s performance is affected. As this occurs quite regularly, I have reached the conclusion that many organisations are losing productivity and suffering lower performance simply because they have never made the link between these cultural values and their operating models.

Whenever I help organisations clarify their controlling, relating and developing values in this manner, the people in the organisation find the process incredibly illuminating, as it provides explanations of why people are behaving the way they do.

When I provide the same process focused on just clarifying the dominant values held by the leadership team, the results can be very telling. Over the years I have seen a leadership group’s highest-priority shared values be so strongly drawn from one set of values that they always favoured the operating model that best aligned with their own values. For example, when I worked with a strategic planning team in a food and manufacturing plant that had dominant development values and consequently favoured the product leadership strategy. However, after sharing this bias with the team and revisiting the organisation’s need for growth into new markets, they quickly realised that better and newer products were not what they needed; in fact, cheaper, faster delivery was. They were then able to use their values preference of developing to consider how they could create cheaper, faster delivery to gain access into lucrative overseas markets.

In another case, I worked with a broadcasting organisation that favoured operational excellence operating models. At the time they were trying to work out how to gain more advertising from specific clients. Because of their values bias, they constantly came up with ways to offer cheaper packages of advertising to attract additional business from clients. But whatever they offered to clients didn’t seem to work. When I made them aware of their strategic bias and showed them they favoured operational excellence, it suddenly dawned on the team that maybe the customer didn’t want cheaper prices at all. Maybe they wanted a closer working relationship with greater input and expertise from the broadcaster. Or maybe the clients wanted innovative advertising packages to break into new markets and not cheaper packages to continue to advertise to their established markets. Both options turned out to be popular with clients and sales boomed.

In a final example, I worked with a leadership team in an insurance organisation that was dominant in the relational values and naturally leaned towards favouring a customer intimacy strategy. Having pursued this strategic focus, they had in fact made good ground in attracting new clients and maintaining established ones too. The problem was sales had begun to plateau. On highlighting the bias they had for customer intimacy, I was able to facilitate their consideration of the other two strategic approaches to explore new opportunities. As a result of their efforts, the company developed a series of new insurance offerings and increased sales from both new and existing customers.

The point is that, just because the leadership teams combined personal and highest-priority shared values and so favoured a particular operating model did not mean that this was the best choice for the business or its customers. This type of strategic bias inevitably ends up leading to a decrease in performance and productivity.

As we learned in an earlier chapter, culture on average has eight times more impact on an organisation’s performance than the chosen strategy. Which means that if the existing operating model, instead of being aligned with the leadership’s personal values, was misaligned, the leadership team’s culture is likely to constantly be sabotaging the strategy.

To better understand how the cultural values can have such a dramatic impact on the organisation’s performance we need to understand a little more about the role and impact of human values.

Understanding values

What are values? How do they differ from morals and ethics? How do values function and what is their role in an organisation? Are they as important as many organisations say they are? How do values contribute to an organisation’s performance? Each of these questions deserves some exploration to really understand the power of values and their influence inside a culture, especially in an above the line culture. Let’s begin our investigation of values with the obvious question.

What are values?

There are many ways of defining values, ranging from motivation descriptions through to academic ones. After 20 years of working with and studying values, I made my definition of values short, accurate and functional. I define a human value as your ‘preferences multiplied by priority, which highlights your meaning and motivation!’ I recognise that this description looks a little cryptic, so let’s break it down.

Values are preferences

Values can be thought of as a preference because a value is a concept. A value is not a material object or a person or a place; rather it is what these various things represent to us. What they mean to us, and not the things themselves. For example, a house is not a value, but what the house represents to us — a home, security, an investment, a status symbol — is. So a value is a preference because a value helps us identify what we would prefer to experience in our lives, by means of owning physical possessions — house, car, mobile phone, guitar; or relating to specific people, for example through friendship, romance, family, learning, support, healing, business; or engaging in specific activities such as dance, surfing, cooking, gardening, travelling, listening to music or riding a motor bike. For an organisation the preferences might be to grow, survive, compete, deliver, service, return, share or lead.

As you can imagine it doesn’t take long for the preferences to become numerous. Because both individuals and organisations usually have multiple preferences it becomes important to prioritise these preferences in order to understand which are the most important, or at least important, to us.

Values as priorities

In a previous book, Finding True North: Live Your Values, Enhance Your Life, I wrote on personal values. I explained that in order to experience happiness and fulfilment in life, ‘the most important thing is to know what is the most important thing’. The same applies to values. The most important thing to know about your values, personal or organisational, is which are the most important values. The reason is that until we have put our values into a hierarchy of importance we may find ourselves torn between conflicting values. The only way to resolve a values conflict is to understand which values are more important to you and then act accordingly! When you have a values hierarchy, you can make a clear distinction about the appropriate decision to make and then act on this with no other values in friction or resistance.

So if we work with values as our preferences multiplied by the priority we place on the individual preferences, we end up with clarity. Let me show you an example of how this might work. Imagine an individual has a preference to experience the following in their life:

- health

- family

- security

- employment

- fun

- adventure

- learning.

If they were to simply start living these values without prioritising them, they are likely to quickly find some of the values in conflict with one another. For example, being employed may reduce the amount of time they get to spend with their family and, due to the stress they might experience at work, jeopardise their health. Or they may find that pursuing their desire for adventure puts their value of health, family and security at risk. However if the person is able to do the necessary deeper contemplation and understand their prioritisation of these values, suddenly the most important things are clearly understood as the most important things and so the individual can think, plan and act accordingly without feeling guilty or stressed about their choices, as they already know what is most important to them. So let’s say the person prioritises their values in the following manner:

- family

- health

- security

- fun

- learning

- employment

- adventure.

Now the individual has a clear sense of where to put their attention, time, money, energy and quality. With family defined as the value that is most important, then even having less time for adventure becomes an acceptable trade-off as the individual has made a clear decision and commitment to invest themselves in family first. Does this mean they never get to indulge their passion for adventure? No, of course not. What it does mean is that they will happily scale the quest for adventure to fit into their higher priority for family. It also means they look for different ways of experiencing adventure, perhaps in ways that include rather than exclude family participation, or in ways that only take a few hours at the weekend rather than a whole weekend away from family.

An organisation’s official values may be set by the same process. Let’s imagine an organisation has this set of values:

- integrity

- respect

- customer service

- growth

- innovation.

Without having a sense of hierarchy applied to the values, we can again immediately see how some of these values could end up in conflict with one another. For example, if the organisation puts time, money, people and energy into growth and innovation, it might reduce the necessary dedication and focus required to deliver on customer service, which would mean the organisation was out of integrity, claiming to be committed to service but then taking its eye off the service ball. That’s not to say any organisation investing in growth and or innovation will therefore drop its standards in service, but it could, and organisations often do! However if the values are prioritised, we might end up with the values listed like this:

- customer service

- integrity

- respect

- innovation

- growth.

Suddenly we have a clear mandate for prioritisation of decision making across the organisation. Growth and innovation, for example, will still be applicable and executed, as long as these priorities have no detrimental impact on customer service.

All of this exploration and explanation of preferences multiplied by priority bring us to the final part of the equation, which is meaning and motivation. In short, once values are placed in a hierarchical order and understood, then people can grasp the meaning embodied in the values — for example always put family, or customer service first — and will be motivated to act accordingly.

Having defined values, let’s now move onto the next question in our list.

How do values differ from morals and ethics?

Values are about preferences and priorities. Morals are a perspective of what is right or wrong, good or evil. Ethics are a group’s agreed-upon code of behaviour.

Values, morals and ethics can be interlinked. For example, considering our previous hierarchy of values in a company, if we value customer service as our highest-priority value, then we would consider it to be wrong to treat a customer badly, or rudely. In order to ensure no employee did so, the organisation might draw up a list of behavioural guidelines that they ask everyone to abide by. Things such as always be polite in your tone, words and behaviour; always listen and ask questions before responding to the customer’s needs; and be empathetic, and try to put yourself in the customer’s shoes.

Although values, morals and ethics do often interlink, they also have significantly different definitions and roles.

How do values function?

Values are incredibly influential on people’s performance and behaviours. By exploring some of the ways that values influence us we can begin to see how they play such a large role in determining our behaviours and performance. Our values can influence us in many ways.

Values direct our attention

Our personal values operate in very much the same way that an internet search word does. Values enable the brain to focus our attention onto a singular topic. Imagine you wanted to hire a speaker for your next conference to come and talk to the leadership team or staff about the importance of culture to organisational performance and staff fulfilment. You might open an internet search window and type in the words ‘company culture expert’. The moment you hit the enter button on your keyboard you will be presented with a list of sources and options regarding speakers for your conference. The search word you typed in enables the internet search engine to isolate from the whole of the world wide web the options that are most closely aligned with your search interest.

Your personal values act in exactly the same way: they inform the reticular activated system in your brain, which maintains consciousness and acts as a filter, which in turn enables us to concentrate on what is most important to us and ignore everything else. Knowing which are your highest-priority values enables you to focus effectively on accessing and experiencing what you want, without being led astray or distracted by less important ideas, activities or topics. It is very important for people to know their personal values to ensure they are aligned with the type of work they are engaged in. People with values that are aligned with the work they do are more focused and productive, and more emotionally and mentally rewarded by their work. People who have minimal alignment between their values and the work they are engaged in have the following common symptoms. They are:

- less focused

- less productive

- more prone to mistakes

- more prone to absenteeism

- more likely to quit their jobs

- more inclined to suffer from boredom

- more likely to badmouth the work environment when talking with colleagues.

Values generate motivation

As we discovered earlier in this book, all human values fall into three broad categories of motivation: controlling, relating or developing. This means that an individual’s personal values, regardless of their position in the organisation, influence the way in which they choose to relate to other people in the organisation, colleagues and customers alike; how they pay attention to ensuring and maintaining an element of control around such topics as productivity, safety, management, quality and the like; and to what extent and in what manner they see the need for their own or the organisation’s growth, learning, development or improvement. The combination of focus, attention and importance on controlling, relating and developing is unique to each individual and influences directly why and how they do anything!

Values generate energy

If you have ever found yourself so involved in a piece of work, conversation, task, book, movie or song that you felt energised just by being attentive, you have felt your values at work. When you are engaged in an activity that is closely aligned with your values, you will have felt no sense of time, no need for sustaining food or drink — or if you did it felt like an interruption, something to be achieved as quickly as possible so you could get back to what you were doing. Alternatively, you will have noticed that when an activity was not aligned with your values, time dragged, your energy levels dropped, you needed all sorts of sustenance or energy-providing resources to keep you going. Why the difference? Values that are aligned to an activity generate energy. Values misaligned to an activity drain energy.

Values define what to say yes and no to

Given our values are as we discovered earlier in the discussion of our preferences and priorities, they lead to us voicing our opinion in terms of yes or no, depending on whether the question being considered aligns with our highest priority values or not. If something aligns with our values we will say yes.

Values define what is worth striving for

Our personal values define if we will embrace the company values, and if we are willing to strive for our goals or the organisation’s objectives. I constantly remind people in organisations that the real power of the company culture comes from their personal values. Organisational values only become effective when people in the organisation can align their personal values with them. Otherwise the personal values will remain the dominant factor in determining people’s behaviours.

The role of values in an organisation

All values have one of two distinct roles. They are either a goal value or a means value. A goal value is a value that is an end objective — the end result or outcome we are aiming for. A means value is any value that provides a way of achieving the goal value. A means value is the means to achieving the goal. If a goal value is profit, a means value for profit would be productivity, efficiency or management. Most goal values have multiple means values.

Within an organisation we can also look at the company values as goal values. The employees’ personal values, when aligned with their work and the organisation, are the means values. In other words, through people delivering on and through their own personal values that are aligned with the work they are engaged in, they deliver a performance that takes the organisation towards the company goals. This is an aspect of values alignment that is little understood by organisations, and yet it directly affects performance. Organisations that clarify and define their company values, but do no work on supporting employees to identify and align their personal values to their work and the company values, are probably wasting their time. Personal values have significantly more impact on employees’ levels of commitment and motivation to excel through and with their work than the organisation’s values.

Research by Kouz and Pousner, two academics from Santa Clara University in the United States and authors of the book The Leadership Challenge, has shown that people’s understanding of the organisational values makes little difference to their levels of commitment to their work compared with people clarifying their own personal values and the degree of alignment these values have to the work they do. It is only when people’s personal values align with and do not contradict company values that the latter will be embodied in people’s decisions and behaviour. In this manner we can begin to see how people’s personal values are the means to the organisation’s goal values being delivered. Finally, people who share similar or even the same values and give them similar priorities are likely to get on well. So well, that they will form and build a culture around and upon those shared high-priority values.

Are values as important as organisations think they are?

Having reviewed the role of values, we can see that they are very important to organisational culture and performance. People who believe that values are soft or touchy-feely do so out of naivety. Any half-sensible businessperson who understands even half of what values do and how they function will see the power and influence they have over performance. Without values, nothing happens. Values are the invisible threads behind so much of what organisations take for granted or are interested in achieving. Here is a short list of some of the most common ways in which values contribute to an organisation’s results and performance:

- Values determine why customers choose you and your products and services.

- Values determine why people choose to join and leave your organisation.

- Values determine how much discretionary effort people will put into their work.

- Values determine whether people enjoy working with their colleagues or respect their superiors.

- Values determine whether shareholders will buy your shares.

- Values are at play in determining whether the merger or acquisition of your organisation with another, or theirs with yours, will be effective.

- Values are the underlying influence on every one of the thousands of decisions and behaviours that are made across your organisation every day.

- Values determine people’s buy-in to the company culture, vision, mission and strategy.

- Values even influence which strategy the leadership team selects.

- Values determine whether your people will get along with each other.

- Values are people’s means to living their organisation’s goal values.

- Values are the evaluation filters that every goal and objective is subconsciously tested against by everyone. If the goals and objectives are not aligned with the values, the values win. Every time. No exception.

Having had an in-depth look at the roles of values in organisations, we are now ready to extend our focus and thinking to the wider context in which all human values function. That context is of course culture, which can occur in two dominant forms, which I refer to as above and below the line.