Zane C. Barnes

CONTENTS

13.3 Different cleaning requirements

13.5.4.1 Process Mains Cleaning

13.5.4.2 Process Vessel Cleaning

13.6.1.1 Process Vessel Cleaning

13.6.1.2 Process Main Cleaning

13.1 INTRODUCTION

Hygiene control and plant cleanliness are essential. Soiled equipment will add taints to beer, and the presence of spoilage microbes will result in the development of beer turbidity and off-flavors.

Traditionally, a brewing plant was dismantled and hand-cleaned, which was time-consuming and meant that only mild detergents and low temperatures could be used. In today’s modern automated brewery, this method is not practical.

The physical size of a 10-m diameter lauter tun or a 20-m-high cylindro-conical fermenting vessel presents obvious challenges for manual cleaning. Much of modern processing equipment, such as centrifuges, filters, and plate heat exchangers, cannot be opened conventionally and quickly. Also, complex valve manifolds for automatic routing of extensive pipework networks cannot be readily dismantled.

It has become a requirement that all equipment is enclosed and that all internal surfaces in contact with the product can be deterged and disinfected by internal circulation of cleaning fluids. With no direct contact with people, it becomes possible to consider more aggressive cleaning fluids and higher temperatures provided they are compatible with all parts of the system being cleaned. Equipment is not dismantled and it is cleaned in place (CIP).

13.2 PLANT CLEANLINESS

A clean surface needs to be free from soil or scale. It must have no residual chemicals that have been used for cleaning. Normally, it must also be microbiologically clean.

The removal of microbes is difficult because they can strongly adhere to surfaces. They can find protection in microscopic holes in surfaces, and they can build up surface biofilms that can provide protection from cleaning. In practice, it is very difficult to achieve a sterile surface that is totally free from viable microbes, but disinfection can be achieved where microbiological numbers are reduced to a safe level.

A dirty surface may contain 10 × 106 bacteria/cm2, which by chemical cleaning can be reduced to 10 × 103 bacteria/cm2, and by disinfection with a sterilant can be reduced to 10 bacteria/cm2.

13.3 DIFFERENT CLEANING REQUIREMENTS

Brewhouse vessels become very heavily soiled with proteins, sugars, and hop residues. The hot process ensures wort sterility at entry into the wort cooler. The requirement is for visual and chemical cleanliness to avoid fouling taints in the wort and, importantly, to maintain the heat transfer efficiency across the heating surfaces in mash vessels, kettles, and wort coolers. After the wort cooler, the process is cold; therefore, stringent microbiological cleanliness is required as well as visual and chemical cleanliness.

The fermenting vessels are heavily soiled, particularly at the yeast ring above the beer level. If the brewing or CIP water has hardness, then there is potential for a buildup of a calcium carbonate water scale. Also, there is the possibility of beerstone buildup if calcium oxalate has not been successfully removed in the brewhouse. Water scale and beerstone will reduce the cooling efficiency of the vessel wall jackets and provide protection for microbes against cleaning. In contrast, bright beer tanks are lightly soiled, and the main issues are scale prevention and microbiological cleanliness.

13.4 THE CIP SYSTEM

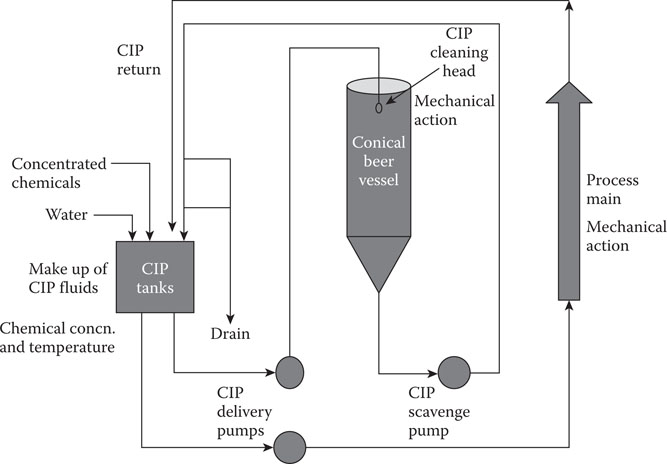

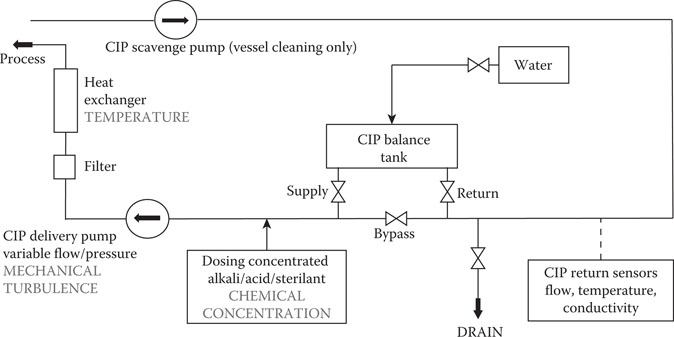

Figure 13.1 is a simplified process flow diagram of a CIP system. It is a series of tanks, pumps, heat exchangers, and chemical dosing sets to provide a supply of varying cleaning fluids at controlled concentrations and temperatures. When a process main is being cleaned, it forms part of a continuous circuit from the CIP set supply to the CIP set return, and the required mechanical turbulence within the pipework is regulated by the fluid velocity generated by the CIP delivery pump (1.5 to 2.0 m/sec).

Figure 13.1 Simplified overview of a CIP system.

When a process vessel is being cleaned, the physical turbulence is provided by the action of the cleaning head inside the vessel. If the vessel cleaning device is a sprayball, it needs to evenly “wet out” all the upper areas of the vessel with a turbulent flow of cleaning fluid in order to create a continuous falling film of liquid down the vessel walls. The CIP delivery pump will need to provide high flow (30 L/min/m of vessel circumference) at low pressure (1 to 2 bar).

If the vessel cleaning device is a rotary jetting head, the CIP delivery pump will need to supply a low flow at high pressure (5 to 7 bar). The high-pressure jets provide a strong mechanical action where each jet impacts at the vessel surface, but this is a confined area. To achieve full coverage of high-impact jets, the cleaning head rotates in two dimensions to a specified pattern.

With either vessel cleaning device, there will be a second CIP scavenge pump connected to the vessel outlet. This is designed to return the cleaning fluid back to the CIP set faster than it is being delivered. The lower part of the vessel relies on falling film turbulent liquid flow for successful cleaning, and this is prevented if the vessel bottom is flooded with cleaning fluid. The complexity of a series of vessel outlets connected to several common process mains as well as the CIP return main are covered in a later section on the design of valve manifolds and hygienic mix proof valves.

13.5 CLEANING EFFECTIVENESS

The four main factors that the CIP set can use to influence cleaning effectiveness are: time, temperature, chemical concentration, and physical turbulence.

13.5.1 Time

The longer the cleaning fluids have to flow over surfaces, the more effective the clean will be; but there will normally be a limit on the time available for cleaning, and also pumping energy is being consumed for the duration. Time can be reduced by increasing one of the other three cleaning factors of temperature, chemical concentration, or physical turbulence.

13.5.2 Temperature

Cleaning action is enhanced by temperature. A 10°C increase in temperature will increase cleaning efficiency by 50%. If a clean at 30°C takes 30 minutes, then at 50°C it can be achieved in 7.5 minutes. However, higher temperatures increase corrosion, and some plant equipment and seals cannot tolerate these higher temperatures. This generally means that hot process vessels (brewhouse) are cleaned hot and cold process vessels are cleaned cold. Process mains are physically sturdier than vessels and are generally designed to be cleaned hot. The hotter the clean, the more disinfection occurs.

13.5.3 Chemical Concentration

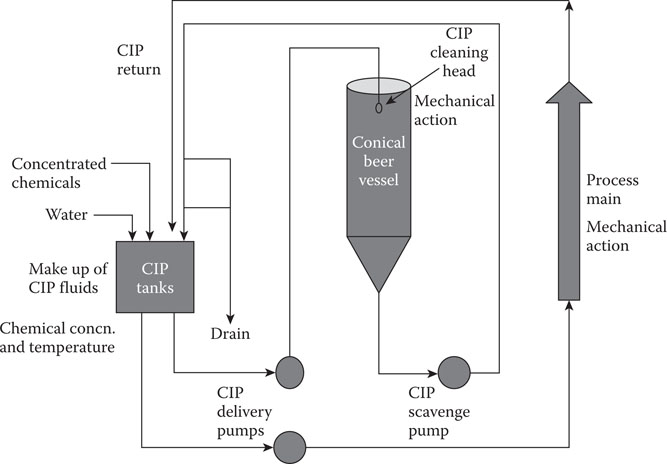

A detergent is required to penetrate and solubilize the soil to remove it from the surface and not to allow its redeposition on the cleaned surface. As might be expected, increased detergent concentration will increase cleaning effectiveness. However, as Figure 13.2 demonstrates, for caustic, this is only true up to a point. Increasing the caustic concentration beyond 2.5% (w/w) will raise chemical costs but with little improvement in cleaning effectiveness.

Figure 13.2 Detergency effectiveness increases with strength up to a point.

Various detergents are used for different soil types. Generally, an alkaline detergent will be used for organic soils and an acid detergent will be used for scale and beerstone. However, careful consideration is also needed for the compatibility of the detergent with the materials that constitute the plant and the process conditions.

13.5.3.1 Alkaline Detergents

An alkaline detergent such as caustic is excellent for removing organic soils, and its high alkalinity provides some disinfection. It is relatively inexpensive. However, alkali will corrode aluminum. It will also rapidly react with the residual carbon dioxide (CO2) atmosphere in vessels to form sodium carbonate, and great care is required to ensure that the resulting vacuum can be adequately relieved to prevent a disastrous implosion of the vessel!

Table 13.1 shows that the resultant increasing levels of sodium carbonate in the caustic solution reduce its powers of detergency and disinfection. Sodium carbonate only has 15% of the cleaning effectiveness of caustic solution. The caustic strength in a CIP set will normally be controlled by measuring its conductivity, and a 2% (w/w) caustic solution will have a conductivity of 93 ms/cm at 25°C. However, sodium carbonate also registers as conductivity and therefore, when present, means that the measured conductivity is giving a false high indication of the causticity and hence a false high indication of detergency capability. Conductivity values also increase with higher temperatures, and this needs to be taken into account when calculating the strength of the caustic.

Table 13.1 Sodium Carbonate only has 15% of the Cleaning Effectiveness of Sodium Hydroxide

% Caustic |

% Carbonate |

Detergency Effect |

Germicidal Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

2 |

0 |

7.5 |

4 |

1 |

1 |

6.3 |

3.7 |

0.5 |

1.5 |

3.3 |

2.9 |

0.25 |

1.75 |

1 |

1 |

Alkali conditions and increasing temperature promotes the precipitation of calcium hardness water salts to form a scale buildup. If soft water is not available for the CIP, then the caustic solution will require either a chelating agent (e.g., gluconate) to bind the calcium and keep it in solution or a sequestrant (e.g., phosphonate), which will prevent calcium carbonate crystal growth and its deposition onto surfaces. These additives will also improve detergent effectiveness by promoting dissolution of soils containing calcium and help prevent the redeposition of solubilized soils. A wetting agent (surfactant) will generally be used to reduce surface tension and improve contact with the surface being cleaned. This also improves soil penetration, soil dispersion, rinsability, and faster drying of the cleaned surface.

13.5.3.2 Acid Detergents

Acid detergents are less effective at removing heavy soil and therefore tend to be used for cleaning vessels downstream of the brewhouse. Acids in a carbon dioxide atmosphere do not have the problems associated with using caustic (loss of CO2, loss of detergency, influence on conductivity control, and vacuum risks). Acids prevent water scale and beerstone formation and remove moderate soiling. They are easier to remove by rinsing after detergent use and are used cold. Phosphoric acid is the more user-friendly acid and is widely used for low organic soil removal and scale prevention. If beerstone has formed, then sulfuric acid is a more effective descaler. If water scale has formed, then nitric acid is a more effective descaler. Organic acids such as citric or lactic are good at soil removal and less challenging for waste water treatment plants. However, organic acids will not descale.

13.5.3.3 Sterilants

If cold cleaning is used, it is common practice to carry out a sterilant rinse after the detergent clean to kill any residual microbes. Many of these sterilants leave residues that are harmful to the beer. For example, halogenated acids give flavor taints, and quaternary ammonium compounds are detrimental to beer foam. In this instance, the sterilant after its contact time is rinsed with microbe-free water.

It is possible, particularly with acid detergents, to have a sterilant within its formulation, which is then rinsed with the detergent and obviates the extra sterilant/rinse step in the cleaning program. Some sterilants have breakdown residues considered not to be harmful to beer and therefore can be used without a postwater rinse. An example is peracetic acid at (0.5% w/w), which is also known as peroxyacetic acid (PAA).

13.5.4 Mechanical Action

It has been discussed previously that there are limitations to increasing temperature and chemical concentration to improve cleaning effectiveness. Increasing mechanical (scouring) action can be used to great affect by the CIP set to improve cleaning effectiveness and therefore to reduce cleaning time, temperature, and chemical concentration.

13.5.4.1 Process Mains Cleaning

The mechanical cleaning action for pipework is defined by the cleaning fluid velocity. Faster flows provide greater turbulence to help dislodge surface residues from internal surfaces. Turbulence is defined as a Reynolds number (RE) greater than 3,000. This equates to a minimum fluid velocity of 1.5 m/sec. Design is usually at 2 m/sec. Higher velocities will produce greater turbulence, but this does not increase the cleaning effectiveness and does increase the likelihood of severe vibration water hammer shocks during stop/start conditions. Table 13.2 shows the CIP flow requirements for different pipework diameters.

Table 13.2 CIP Flowrates for Turbulent Flow in Pipework

Pipe Size |

Pipe Internal Diameter, mm |

Velocity |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

1.5 m/s |

2.0 m/s |

|||

Flow |

||||

Imperial |

DN |

hL/h |

hL/h |

|

2″ |

50 |

47 |

94 |

126 |

3″ |

80 |

77 |

215 |

335 |

4″ |

100 |

97 |

400 |

533 |

6″ |

150 |

147 |

918 |

1,220 |

Process mains are generally cleaned with hot caustic at 70°C to 80°C at a concentration of 1% to 2% (w/w) caustic. This has the added advantage of significant disinfection. Careful pipework design is needed to ensure successful cleaning of a process main. If there is varying pipework diameter in the circuit, the minimum velocity must be referenced to the largest pipework diameter where the lowest velocity will occur. Unions and fittings should be kept to a minimum. There should be no elaborate pipework creating dead-legs and pockets of nonturbulent flow.

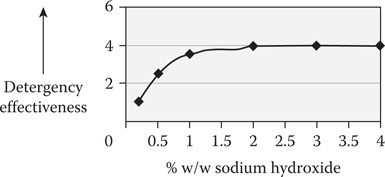

Figure 13.3 shows that pipework bends should be smooth and curved because sharp corners are difficult to clean. There should be no pipework dead-legs, where it is possible to have stagnant nonturbulent pockets. Any dead-leg must not be greater the 1.5 times the pipework diameter, and its orientation to the CIP fluid flow must be correct. Pipe runs should be level or downward sloping with no changes in vertical direction where air can be trapped and create pockets that will not be effectively cleaned.

Figure 13.3 Ineffective CIP due to dead legs and sharp bends.

13.5.4.2 Process Vessel Cleaning

In this case, the CIP mechanical action is defined by the fluid flow and pressure delivered by the cleaning head within the vessel, which in turn is provided by the CIP set delivery pump. The options are for either low-pressure, high-flow cleaning heads or high-pressure, low-flow cleaning heads.

13.5.4.2.1 Low-Pressure, High-Flow Cleaning Heads

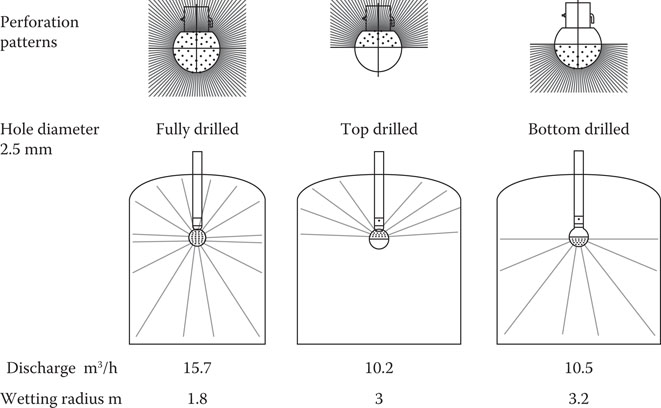

These spray heads need to completely wet the vessel surfaces and create a continuous falling film of CIP liquid under turbulent flow conditions. This film is around 0.5-mm deep and runs down the tank in waves. The flow factor to achieve this, depending on the degree of soiling, is typically 30 l/min/m of tank circumference (diameter times pi). For a 2.75-m diameter tank, the spray head discharge flow rate will need to be 2.75 × 3.142 × 30 = 255 l/min = 15,553 l/h = 15.55 m3/h. Figure 13.4 shows that this can be achieved using a 65-mm diameter fixed sprayball having 2.5-mm perforations in pattern A (360°). At 1 bar of pressure, this would have a wetting radius of 1.8 m, more than adequate for the 1.375-m tank radius. The static sprayball is generally not used for vessel diameters above 3 m. There are no moving parts that require maintenance, but regular inspection is essential to confirm that the perforations are not blocked by debris or water scale.

Figure 13.4 Typical static sprayball design—Ball diameter 65 mm, pressure at head 1 bar.

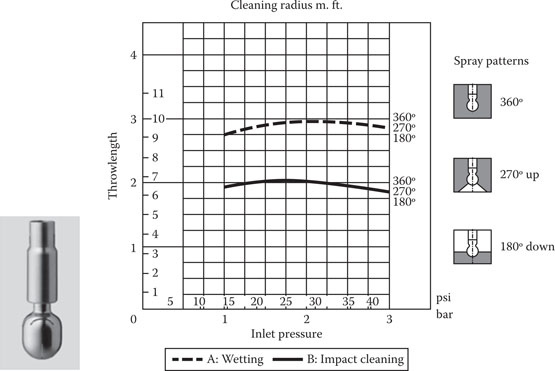

The low-pressure spray from each perforation of the static cleaning head directly impinges at the same localized spot on the surface, and the areas between these impingement spots rely on cascading fluids for cleaning effect. For more challenging soiling, some improvement in cleaning efficiency can be achieved by using a spinning spray head, as shown in Figure 13.5.

Figure 13.5 Typical rotary slotted sprayball. Wetting throwlength is circa 50% greater than impact cleaning throwlength.

Instead of a large number of perforations, this cleaning head has a small number of slots and it spins. The slots in the cleaning head create rotating liquid fans that provide a more complete impingement over the surface. The spinning fan sprays rely on impact to create more mechanical action, and there is now a distinction between the fan spray cleaning throwlength, the distance at which the head effectively cleans, and the fan spray wetting throwlength (i.e., the distance at which the head only provides wetting). The effective cleaning throwlength will be approximately half that of the wetting throwlength. Spinning spray heads are generally limited to an effective cleaning throwlength of 2 m (and a wetting throwlength of 4 m) and therefore will generally not be used for vessel diameters above 4 m. Regular inspection is required to ensure the correct spinning action is being achieved. The flow from a spinning sprayhead will be about 75% of the static sprayball, and the pressure requirement will be 2 to 3 bar.

13.5.4.2.2 High-Pressure, Low-Volume Cleaning Heads

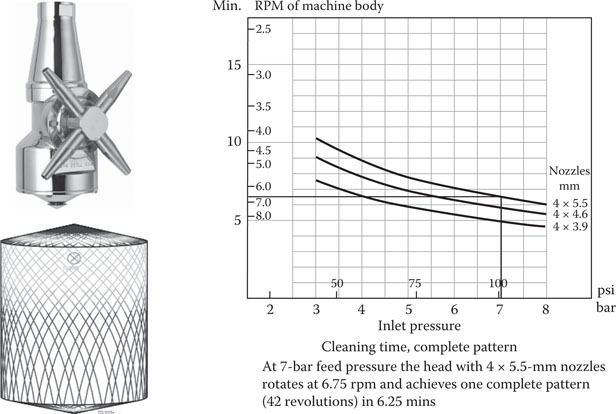

Vessels with more difficult soiling (brewhouse and fermentation vessel yeast rings) require a higher degree of mechanical action, and any large-diameter vessels with a required cleaning throwlength greater than 2.0 m will require the use of a rotary jet cleaning head as shown in Figure 13.6. This provides a small number of high-pressure jets powerfully impinging at a small footprint at the vessel surface. To provide this high-impact effect over the entire vessel surface, the jets are biaxially rotated. The pattern is affected by the number and size of nozzles and the speed of rotation.

Figure 13.6 Rotary jet sprayhead—cleaning pattern after two cycles—eight cycles for complete pattern.

The cleaning head speed of rotation depends on the CIP delivery pressure. If a cleaning head has four 6-mm nozzles and is supplied with CIP fluid at 7 bar, then the head will rotate at 3.7 rpm, and each complete coverage pattern will take 12 minutes. (At 4-bar delivery pressure, the rotation will be 2.8 rpm, and each complete coverage pattern will take 16 minutes.) The flow from a rotary jetting head will be about 50% of that of a fixed static sprayball.

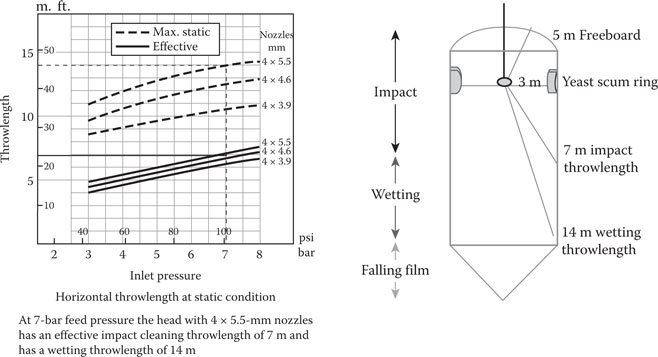

For this 4 × 6-mm nozzle cleaning head, at 7-bar delivery pressure, the cleaning throwlength is 7 m and the wetting throwlength 14 m. How this interacts with a tall cylindro-conical vessel is shown in Figure 13.7. This 6-m diameter vessel operates with a freeboard of 5 m above the liquid level. If the rotary jet is positioned at the working liquid level, then it will effectively clean the 5-m headspace above the liquid level and also the 7-m of wall section immediately below the liquid level. It will effectively wet the next 7 m of lowest section wall, but the cone area will only be cleaned by falling film turbulence. The nature of the soiling in the lower areas may require more mechanical effort, in which case a rotary jet with two 10-mm nozzles at 7-bar pressure could achieve an effective cleaning throwlength of 11 m and a wetting throwlength of 22 m.

Figure 13.7 Rotary jet cleaning head cleaning throwlength.

13.6 CIP PROGRAMS

CIP cleaning programs follow similar principles to that outlined in Table 13.3. The first step will be to water rinse (prerinse) the equipment for a specified time in order to remove the loose fouling debris to the drain. The next step will be a chemical wash to deterge the equipment for a specified time. The recirculating cleaning fluid, depending on the equipment to be cleaned, will be alkali, acid, or it might be alkali followed by acid. The detergent will be controlled for the appropriate strength and temperature required for effective removal of each soil type.

Table 13.3 A Fermentation Vessel CIP Program

CIP Phase |

Duration, min |

|---|---|

Prerinse |

10 |

Alkali wash |

30 |

Alkali postrinse |

10 |

Acid wash |

30 |

Acid postrinse |

10 |

Sterilant wash |

20 |

Sterilant postrinse |

10 |

Total |

120 |

After the chemical wash, and between the alkali followed by acid washes, the equipment will be water rinsed (postrinse) for a specified time to remove all traces of detergent that would otherwise taint the beer. The rinse water needs to be microbe-free. The deterged and rinsed equipment, if not cleaned by a hot alkali wash, may then be disinfected with a recirculating cold sterilant wash to reduce microbes to a safe level. If the sterilant used is detrimental to beer quality, then it will be rinsed (final rinse) with microbe clean water to remove all traces of sterilant. The cleaning program is controlled by the CIP set. This will either be a single-use CIP or a recovery CIP set.

13.6.1 Single-Use CIP Set

Figure 13.8 shows a single-use CIP set. The cleaning solutions are freshly made up for each cleaning cycle, and after a single use are disposed to the drain. The CIP delivery pump has variable speed control and a back pressuring valve that responds to the flow and pressure sensors. This allows delivery of the different requirements for process main cleaning (high velocity), process vessel cleaning with static sprayball (high flow/low pressure), or process vessel cleaning with rotary jetting head (low flow/high pressure). The in-line filter is designed to remove particles that could cause blockages in the vessel cleaning devices. The in-line heat exchanger regulates the detergent temperature when hot CIP is required. The CIP return line sensors confirm that the specified requirements for flow, detergent strength, and temperature have been achieved. The CIP scavenge pump will be used for process vessel cleaning and is not required for process main cleaning.

Figure 13.8 Single-use CIP set.

The mode of operation is different between process vessel cleaning and process main cleaning.

13.6.1.1 Process Vessel Cleaning

Vessel Prerinse. The balance tank is supplied with fresh water to feed the CIP delivery pump to the cleaning head in the vessel. The returning soiled water from the process vessel CIP scavenge pump is directed to drain close to the balance tank return.

Vessel Alkali Wash. The CIP scavenge pump is stopped while the CIP delivery pump continues until it has built up a specified volume of fresh water in the process vessel. The process vessel being cleaned now replaces the balance tank as a reservoir of cleaning fluid, and a circuit is established from the vessel outlet to the CIP scavenge pump, along the CIP return line, bypassing the balance tank to feed the CIP delivery pump, back to the cleaning head in the vessel.

Having established this recirculation route, the chemical dosing commences using a positive displacement metering pump from a bulk supply of concentrated detergent. Dosing will be based on an intermittent timed basis until the required conductivity is sensed in the CIP return line sensor. If hot alkali is required, then the steam heat exchanger will be brought into use. Confirmation of the required temperature, conductivity, and flow by the CIP return line sensors is needed before the detergent cycle timer is started.

Vessel Alkali Postrinse. When the required deterging time is complete, the CIP delivery pump is stopped, but the CIP scavenge pump continues to empty detergent from the process vessel, and the return line is directed to drain. When lack of flow to drain is detected, the CIP delivery pump is restarted but is now supplied with fresh water from the balance tank. This continues for a minimum time and until the conductivity of the returning fluid to drain is sufficiently low enough to indicate that rinsing is complete.

Vessel Acid Wash and Postrinse. If required, an acid wash and acid postrinse is now completed in the same manner as for the alkali wash and postrinse—but using a concentrated acid supply.

Vessel Sterilant Wash. Upon completion of the detergent postrinse(s), the system makes up a working strength solution of sterilant from a concentrate in the same way as detergents. The fresh water volume is built up in the vessel being cleaned, and the water is then recirculated from the process vessel outlet, to the CIP set, and back to the cleaning head at the vessel. Sterilant is then dosed using a positive displacement metering pump from a bulk supply of the concentrated sterilant. This is on a timed intermittent basis to create the desired strength. The required metering of concentrated sterilant will be established empirically by the titration of return line samples (conductivity of the working strength sterilant may be too low for the instrumentation to be able to distinguish it from the fresh water).

Vessel Sterilant Postrinse. When the required sterilant recirculation time is achieved, the CIP delivery pump is stopped, but the CIP scavenge pump continues and is now directed to drain to empty the process vessel of sterilant. When lack of flow is detected on the CIP return line, the CIP delivery pump will restart, using fresh water from the balance tank. This final rinsing to drain will continue for a specified time. The CIP delivery pump will then stop, and the CIP scavenge pump will continue until there is a lack of flow in the return line. Finally, the balance tank will be emptied by gravity to the drain.

13.6.1.2 Process Main Cleaning

The principles are similar to vessel cleaning. However, the process main completes a continuous circuit between the CIP delivery pump and the return to the CIP set; therefore, there is no CIP scavenge pump required. Also, there is no process vessel in which the holding volume of working strength cleaning solutions can be made up. Instead the CIP set balance tank is used for this.

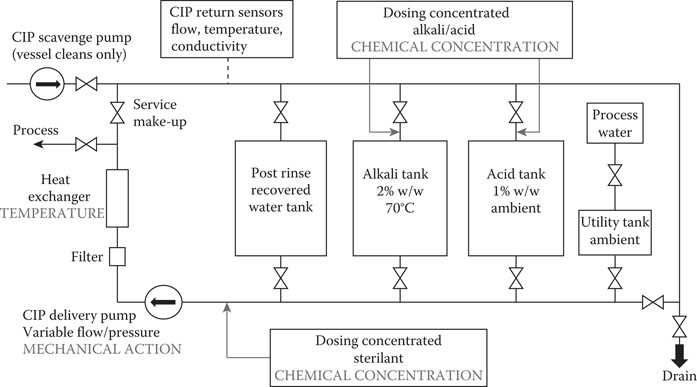

13.6.2 Recovery CIP Set

Figure 13.9 shows a recovery CIP set. This consists of multiple tanks with separate cleaning fluids maintained in operational readiness. Generally, sterilants at working strength are not stable and are made up fresh on-line using the utility tank as a balance tank as per the single-use CIP set. The CIP delivery pump has variable speed control and a back pressuring valve that responds to the flow and pressure sensors. This allows delivery of the different requirements for process main cleaning (high velocity), process vessel cleaning with sprayball (high flow/low pressure) or process vessel cleaning with rotary jetting head (low flow/high pressure). The in-line heat exchanger will regulate the detergent temperature when hot CIP is required. The CIP return line sensors confirm that the specified requirements for flow, detergent strength, and temperature have been achieved. The CIP scavenge pump will be used for process vessel cleaning and is not required for process mains cleaning.

Figure 13.9 Recovery CIP set.

Each tank is continuously controlled as appropriate for level, chemical concentration, and temperature. This obviates the need to make up a full fresh batch of chemicals as part of the cleaning program and reduces the CIP cycle time compared to a single-use CIP set. Also, there is significant reduction in chemical usage as most of it is recovered after each clean. Compared to the single-use CIP set, there is a major reduction in water usage as the prerinse water can be recovered water from the postrinse after the alkali wash. The capital cost and space requirement for a recovery set is higher than a single-use CIP set, but the running cost is much lower. The recovery CIP set will control its tanks to a fixed chemical concentration and temperature and therefore does not offer the full flexibility of the single-use CIP set to provide different cleaning solutions for each different CIP program.

13.7 VALVE MANIFOLDS

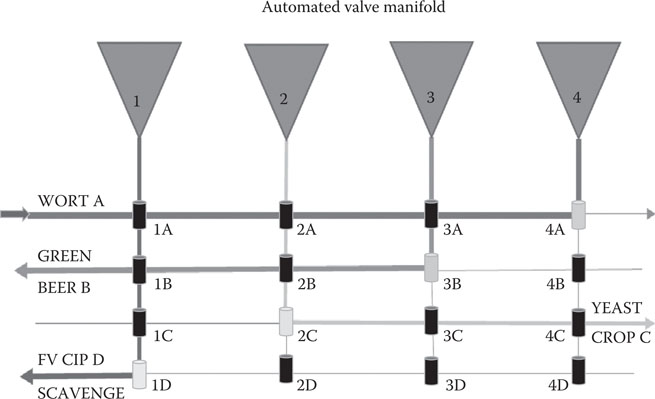

Automated routing around groups of vessels with common services and common outlets has required the development of complex valve manifolds using hygienic mix-proof routing valves.

Figure 13.10 shows a very simplified configuration of a group of four cylindro-conical fermenting vessels (FVs). These are serviced by a common wort main (A) and three common discharge mains for green beer (B), yeast cropping (C), and vessel CIP return (D). (Common top entry mains for pressure control and vessel CIP are not shown.)

Figure 13.10 The risk of cross-contamination between different process liquids and CIP fluids.

The outlet pipework of each FV creates a manifold across the top of the four process mains by use of four mix-proof valves. The FV outlet pipe extends from the bottom of the FV cone to the furthest point on the manifold, normally the vessel CIP scavenge. This may be several meters in length, and if there is no isolation valve at the bottom of the FV, then the whole of the outlet pipe and its manifold connections are always open to the FV and it remains outside the envelope of the vessel temperature control.

If we consider wort filling into FV4, the wort passes straight through the other FV wort connect valves 1A, 2A, and 3A, before it is connected to FV4 by wort connect Valve 4A. This then fills the FV4 with wort and pitched yeast until the wort main is finally purged with hot brewing water to the wort connect Valve 4A, which is then closed to isolate FV4 from the wort line. However, the FV outlet pipe and its manifold are full of wort/yeast and are outside the temperature control of the FV. With additional isolation valves and the use of tank outlet valves, it would be possible to purge the outlet pipework and manifold clear of product, but this would be a major increase in complexity and cost. Generally, this connecting outlet pipework is insulated from the ambient temperature.

If we consider FV2 carrying out yeast cropping, the manifold yeast crop connect Valve 2C opens to the yeast cropping line, and yeast passes straight through yeast crop connect valves 3C and 4C to a yeast cropping pump. However yeast is also free to backfill the line via yeast crop connect Valve 1C. This can be dealt with by a clean of the cropping line when cropping is complete, but the outlet pipework from FV2 and its manifold remain full of yeast/green beer, which again is outside the envelope of the vessel temperature control.

If we consider green beer transfer from FV3, the manifold connect green beer Valve 3B opens to the green beer transfer line, which allows beer to pass straight through the green beer connect valves 2B and 1B to a green beer pump. However, the green beer transfer line can also backfill the main through manifold green beer connect Valve 4B. Isolation valves will determine the length of this dead-leg, and the water flushing design with deaerated water needs to minimize process losses.

The CIP fluid of FV1 will flow the length of the outlet pipework and to the farthest point of the manifold to the manifold CIP return connect Valve 1D to ensure the whole manifold is cleaned. Generally an FV will be cleaned with a low-flow, high-pressure rotary jetting head, and this may result in a partial full pipework manifolds and fluid velocity less than 1.5 m/s, resulting in incomplete cleaning. This can be partly overcome by allowing an intermittent buildup of cleaning fluid in the bottom of the vessel and then intermittently pumping full pipework and manifold at the correct velocity. However, the better solution is for an intermittent backflush of cleaning fluids through the manifold and vessel outlet back into the vessel and back again, both at the required minimum velocity.

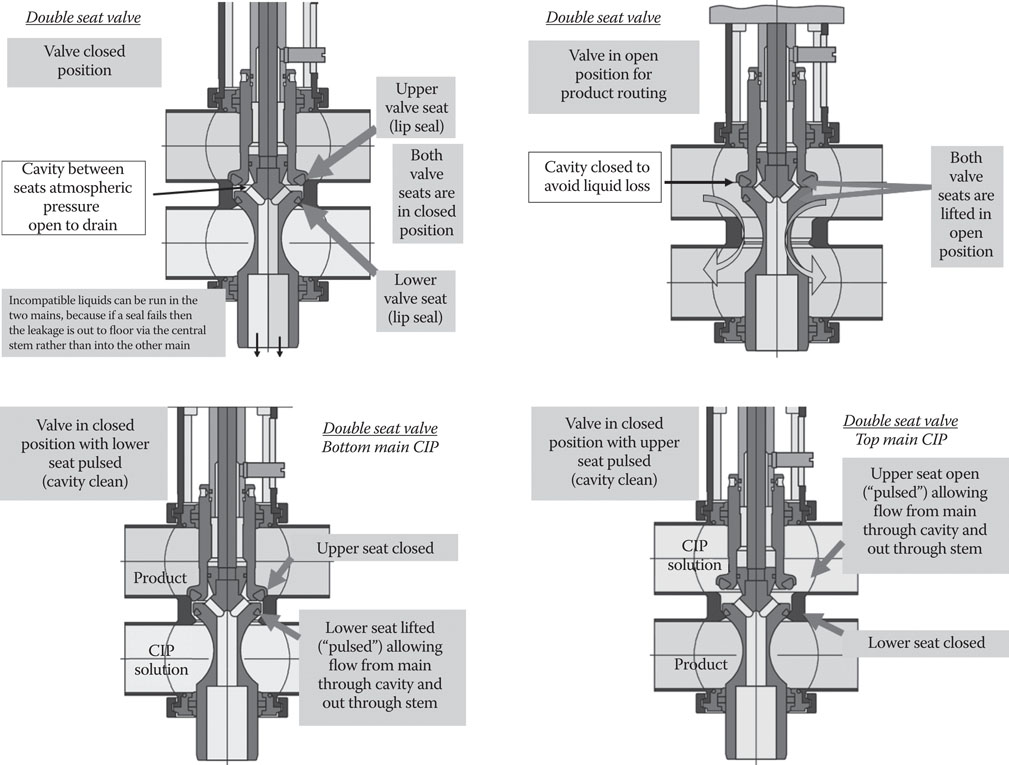

13.8 MIX-PROOF VALVES

As well as the potential process dead-legs due to pipework valve configuration, there is also the constant risk of product crossover, beer loss, and CIP contamination at each of the manifold connect valves. To avoid this, these valves need to be of the mix-proof design similar to that shown in Figure 13.11. The seals between the two process lines are separated by a cavity at atmospheric pressure so that any seal leakage cannot be forced into the other process line. Any such seal failure will be observed as a telltale leakage at the bottom of the valve, and the capture drain trays underneath need to be located so as to be easily visible by operational staff. During CIP of a main, the associated valves either have cleaning fluids intermittently pulsed into the cavity, or the valve seats involved in the clean (upper or lower) can be intermittently pulsed open, which subsequently cleans the face of the seal as well as the cavity.

Figure 13.11 Hygienic mix-proof valves.

13.9 CLEANING VALIDATION

Wherever possible, regular visual inspection should be carried out to confirm the physical cleanliness of the vessel (absence of soil and scale). Regular maintenance inspection of cleaning heads is needed to confirm that sprayball apertures are not blocked and that rotation devices are turning correctly. If a rotary jetting head is in use, a rotation sensor (pressure sensor) can be fitted in the top of the vessel. This pressure sensor provides a frequency pattern of pressure spikes due to the turning impacting jets, and this confirms the correct rotation of the jetting head.

The modern CIP set provides indirect assurance of adequate cleaning by confirming the successful completion of the programed CIP parameters of temperature, conductivity (cleaning fluid strengths), and time. It can confirm the correct velocity for main cleaning or the correct CIP flow/pressure for the vessel cleaning device.

A more direct assurance is provided by sampling the final rinse water from the cleaned vessel and testing for absence of residual cleaning fluids (caustic/acid/sterilant) and for the absence of microbes. The latter can be confirmed by laboratory microbiological plating techniques, but it is likely that the equipment will have been put back into use before these results are known. A better approach is for positive release of the vessel using an adenosine triphosphate (ATP) bioluminescence rapid test confirming an acceptable clean.

13.10 RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

Heavy soiling requires a caustic detergent. As discussed earlier, when caustic is used with hard water it precipitates water scale, and in a CO2 environment it rapidly reacts to form sodium carbonate (15% of the cleaning effectiveness of caustic), which risks vessel implosion by the consequent vacuum.

A method that appears promising for cleaning heavily soiled fermenting vessels is to not start with a long prerinse to drain but instead with a short burst of caustic onto the soil, then allowing it to soak. This caustic penetrated soil then readily rinses into the drain. The vessel is then deterged with cold acid (and, if required, a combined sterilant) and is finally rinsed with microbe-free water. This offers a large savings in water and chemicals, reduces scaling, and avoids the risk of vessel implosion due to vacuum.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This chapter is intended to reflect current knowledge and best practice for a brewery CIP. The author has drawn upon past working collaborations with technical representatives of chemical suppliers, particularly Sopura and Ecolab. This chapter would not have been possible without the author’s experience during his employment with Briggs of Burton, where he was actively involved in the design, construction, and commissioning of breweries and their CIP sets worldwide. However, any errors or omissions are entirely those of the author.