EPILOGUE

Whispers from the Grave

By now, it should be evident that these fascinating creatures called dinosaurs played a pivotal role in Earth’s history. Perhaps your newfound knowledge of dinosaurs will enter conversation at parties or serve you in trivia contests with the youngsters in your life. Yet you might reasonably ask (as many have asked me), “What relevance do dinosaurs have today?” Do they serve any utility beyond their entertainment value? Let me try to persuade you that dinosaurs still have much to teach us, if we care to listen.

I’ll begin my case with what may seem an outlandish claim:

Dinosaurs may well be crucial to the continued existence of humanity and much of the planet’s biodiversity.

“Sure,” I can hear you saying, “spoken like a true paleontologist.” But consider this. The asteroid impact (Silver Bullet) hypothesis was put forth to account for the end-Cretaceous extinction of dinosaurs. Scientific study of this impact scenario led to a frightening realization: a future comet or asteroid strike could decimate human civilization and result in the extinction of millions of species, possibly even our own. Research has shown that such near-Earth objects (NEOs) pose a remote but very real threat; collisions with an asteroid greater than 1 kilometer (0.6 mile) in diameter (large enough to generate global havoc) occur every few hundred thousand years or so. In the wake of this insight, research programs led by NASA and other space agencies investigate technological avenues both for the detection and deflection of NEOs. In a related vein, study of the K-T “impact winter” scenario—that is, the global fallout resulting from a major asteroid strike—helped define the “nuclear winter” scenario— the global catastrophe that could follow an all-out exchange of thermonuclear weapons. The latter idea, presented to the U.S. Congress by such well-known scientists as Carl Sagan, has been a profound deterrent for those who might contemplate such military madness. Therefore, it’s entirely feasible that dinosaurs, or at least their modern-day study by geologists and paleontologists, might one day be regarded as an important element in the persistence of humanity. This conclusion underscores the diverse interconnections binding the physical and biological realms, as well as the importance of pure research, which often yields unexpected outcomes.

There’s another way in which dinosaurs just might help “save” our world. We live at arguably the most pivotal moment in human history. Overwhelming scientific consensus confirms that we’ve reached a tipping point in our relationship with the natural world, approaching (and, in some cases, exceeding) the limits of the biosphere to absorb the excesses of human existence.

To focus on a single aspect of this crisis—loss of biodiversity—Earth’s biosphere is currently home to an estimated 13 million species. Biologists have formally named and described fewer than 2 million of these, with an overwhelming emphasis on larger, conspicuous critters. Between 10 and 40 percent of all species (including one in four varieties of mammals) are now threatened, with the numbers of imperiled life-forms rising rapidly. Over the past century, the pace of species extinction has skyrocketed, with recent estimates indicating a rate approaching a thousand times greater than prehuman levels! Paleontologists see evidence in the fossil record of five previous mass extinctions, and we are now on the brink of the sixth such cataclysm—the largest extinction event since the one that killed off the dinosaurs over 65 million years ago. The present panoply of biodiversity, the product of millions of years of evolution, is being wiped out in mere decades, an undetectable blip on the radar screen of deep time. If the current extinction trend continues, about half of all species alive today may be extinguished by the close of this century, with uncertain consequences for the survivors.

A unique aspect of this particular mass extinction is its precipitation by a single species— us. This time around, humans are the asteroid on a collision course with Earth. A recent assessment of global ecosystems—sponsored by the United Nations and carried out by 170 scientists from an array of disciplines—concluded overwhelmingly that this ecological crisis is being driven by human activities. The report’s statistics are staggering: almost 60 percent of coral reefs threatened, more than half of the world’s wetlands destroyed, 80 percent of grasslands imperiled, and 20 percent of drylands in danger of becoming desert. Causes of this dramatic, widespread environmental degradation are all too familiar to most readers: deforestation, human overpopulation, spread of toxic pollutants, overexploitation of animal species, and emission of greenhouse gases leading to global warming. Nature has simply been unable to absorb the punishment delivered by ballooning human populations and increasing consumption linked to industrialization.

Yet, despite the severity of this ecocrisis, we continue to spend our environmental “capital” like some crazed gambler unable to see beyond the next hand of Texas Hold’em. Without a rapid and radical shift in global priorities, we’re headed for ecological bankruptcy, and the effects of this stunning environmental “downturn” will be felt much longer than any squandered pension, housing slump, or devalued currency. Study of previous mass extinctions makes it clear that it would take 5–10 million years to rebuild Earth’s ecosystems to current levels of diversity.

You might now be thinking, “If all species eventually go extinct anyway, why should we care about curbing the current pace of losses?” At some level, the answer comes down to a moral decision. Do you feel that humans have the right to knowingly exterminate millions of species? Put another way, should the nonhuman members of the natural world have any intrinsic rights to survival? And what of future generations of humans that may never have the opportunity to see an elephant, polar bear, or humpback whale? Even if your scope of concern does not extend to other species, it’s important to remember that human civilization, perhaps even the persistence of Homo sapiens, is also at risk.

In short, if we are to avoid a calamitous future, we need a dramatic course change in this century, and almost certainly within the next generation. Of the four thousand or so human generations that have lived and died, the present one may be unique in its capacity to determine the fate of all future generations. Yet the ecocrisis is greatly amplified by another problem— ignorance. Most people have not even begun to comprehend the depth and destructiveness of our present course, or the changes required to alter this path. Instead, as a society we tend to bury our collective heads in the sand while grasping steadfastly onto erroneous, outdated notions. Many presume, for example, that Earth is bountiful enough to supply our growing needs indefinitely and that technological innovations will bail us out of even our most egregious overindulgences. Others, overwhelmed by current environmental woes and the tempo of destruction, assume that there is little room for optimism. Yet awareness of this issue and possible solutions are accelerating rapidly, with more and more people coming to understand that their everyday decisions can have far-reaching, even global, effects. Surely there is hope and optimism to be found in recent efforts to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases and move in the direction of sustainability.

Nevertheless, any meaningful movement toward ecologically sustainable societies will require not only an outward change in technology but an inward shift in worldview. As many authors have argued, long-term sustainability will require that we expand our consciousness and redefine our relationship with nature. In essence, we must shift from a human-centered (anthropocentric) worldview to a life-centered (biocentric) one. As I see it, such a fundamental change will require no less than a transformation of our education system, from K–12 to higher education. We must equip parents and educators with the necessary tools both to communicate the science of natural systems and to foster a passion for nature. Numerous studies agree that this education must be place based and learner centered, and include a generous amount of intimate contact with the outdoors. Today, a variety of factors—from television and video games to fear of traffic and strangers—tend to keep children indoors and prevent them from forging bonds with nature. The affliction even has a name—nature deficit disorder. This indoor trend desperately needs to be reversed. Moreover, the educational curriculum must teach children—and adults—not merely how to further their careers but how to live well in the world and to embrace sustainability.

Recent interest in the importance of environmental education has spawned a movement in ecological literacy, or “ecoliteracy.” Organizations such as the Center for Ecoliteracy in Berkeley, California, promote understanding of local ecological webs and human roles within these webs.1 Proponents of ecoliteracy argue persuasively that designing entire curricula around basic ecological concepts and outdoor activities integrates children with the natural world and encourages growth of a more informed citizenry.

While I applaud the ecoliteracy approach, it seems to me that its advocates have neglected an essential element—transformation. As we’ve seen, everything changes, from the day-to-day composition of our bodies to the deep time parade of species and ecosystems. Life has undergone radical transformations, tracking unbroken lines of ancestors and descendants from humble, single-celled beginnings to astonishing explosions of plants and animals. We humans—upright apes and latecomers on the evolutionary scene—find relatives not only among primates and other mammals, but also among fishes, flowers, and fungi. If we are to survive as a species, it’s imperative that we undergo an evolution of consciousness, adopting a worldview that recognizes this common journey and embraces other organisms as family members deserving of respect. So education must incorporate not only the myriad connections that bind us in this snapshot of ecological time but also the profound transformations that embed us in deep time. Ask any fiction writer or film director—transformation lies at the heart of all compelling narratives.

Cultural historian Thomas Berry goes so far as to claim that much of our present crisis with the environment comes down to a lack of story. We currently do not have a compelling narrative that places humanity into a larger context, so our lives tend to lack a sense of meaning or greater purpose. No longer do we feel the awe, wonder, or sense of sacredness about nature typical of many preindustrial (and present indigenous) cultures. But what should the new story be? Berry’s solution, supported by growing numbers of scientists, theologians, and educators, is the Great Story—sometimes called the Universe Story, the New Story or the epic of evolution—that begins with the big bang and traces our sinuous path to the present day. I gave an abbreviated, dinocentric version of this epic tale in chapter 2, which shares a great deal in common with the human-centered version. Some people view this narrative as the greatest triumph of the scientific revolution, as well as an opportunity to help heal the rift between science and religion and provide that much-needed sense of meaning and purpose. I am one of those people.

Interwoven throughout the Great Story are the ideas of transformation and flow, high-lighting the many ways in which we are not merely connected to but literally immersed in the current of life. Never before has it been so important to see ourselves as temporary, swirling concentrations of energy that arise from the background flow, persist briefly, and then return to that same flow. That flow is a single unfolding whole that stretches back through deep time to the origin of the universe. Humans are not separate from nature; we are nature. Yet science education today remains overwhelmingly stuck in the machine-based perspective of Descartes and Galileo (chapter 1), regarding the nonhuman world merely as a collection of objects rather than, to quote Berry, “a communion of subjects.” In the end, if nature is regarded merely as natural resources, we deny ourselves a meaningful home.

The year 2009, in which I am now writing, is the 200th anniversary of Charles Darwin’s birthday and the 150th anniversary of the publication of his famous tome, On the Origin of Species. Yet Darwinian evolution remains steeped in controversy within the American general public (and in a number of other countries) despite the fact that its core message—the common ancestry of all life on Earth—is accepted as the central tenet of biology by virtually the entire scientific community. I believe that this profound disconnect is due as much to a failure of education as to the antievolution efforts of religious fundamentalists. Universities have not made evolution relevant to their students, particularly to fledgling teachers. Elementary and high school educators not only lack confidence in communicating the nuts and bolts of evolution (mutation, natural selection, speciation, etc.); they are also missing the larger context. All but absent from evolution teaching are the numerous links with ecology and the moment-to-moment flow of matter and energy. Most critically, also missing is the Great Story, that grand epic that encompasses the unified history of life, the universe, and every-thing. As a result, even for those of us who accept its veracity, biological evolution is little more than an intellectual factoid, with virtually no meaning for our lives. To my mind, a bodily, internalized understanding of evolution in the grandest sense will be a key element in defining a sustainable future.

In short, we need more evolution in America’s classrooms, not less. And it must be made explicitly relevant. Evolution isn’t something limited to the distant past. It happens every day and will continue to happen on Earth as long as life persists. Recent research on human development shows that we are all “natural born creationists,” spending most of our child-hood with the firmly held belief that all varieties of plants and animals are distinct entities. In general, it is only from the age of 10 or 11 that children are capable of conceptualizing the kind of transformation inherent in evolutionary change. The Great Story, presented at various age-appropriate levels, has the potential to help us grasp the essence of both transformation and unity. If our education system is to move us toward sustainability, it must foster not only ecoliteracy but evolution literacy, or “evoliteracy.” The combination of these two, perhaps best thought of as “nature literacy,” should embrace both connections (ecology) and transformation (evolution). Bridging the current evoliteracy gap will require that we foster transformative thinking, which brings us back to those “long-dead” dinosaurs.

For several reasons, dinosaurs offer a superb vehicle for teaching science through a combined ecoevolutionary approach. First, unlike many topics in science, dinosaurs inspire rather than intimidate our imaginations. Second, as the primary exemplars of prehistoric Earth, dinosaurs serve as able, even ideal, guides to an exploration of the deep past. Third, the living descendants of dinosaurs, birds, are much beloved and keenly observed, forging a robust link between past and present. It’s not as large a leap as you might think from your Thanksgiving turkey to an ancient tyrant named Rex. Fourth, as demonstrated in the preceding pages, the interdisciplinary nature of paleontology means that dinosaurs provide excellent access points to topics as diverse as genetic cloning and plate tectonics. To give two timely examples, the hothouse world of the Mesozoic is a surprising and informative way to begin discussing contemporary climate change, and the abrupt demise of dinosaurs is a natural starting place for addressing today’s imminent extinctions. Finally, dinosaurs possess tremendous potential to help convey the transformational Great Story and, in doing so, foster evoliteracy.

Never before have humans needed to comprehend the vastness of time—until now. How will we ever promote ecologically sustainable societies unless we first reinsert ourselves into the fabric of time, deriving meaning from our past and contemplating our responsibility to future generations? In direct opposition to this need, our present experience of time tends to be ever accelerating. As adults, our lives revolve around endless series of tasks and pressing deadlines, completely obscuring the larger context of existence. Strangely enough, dinosaurs can offer an excellent means to help anchor us back into deep time. Homo sapiens has existed for a mere nanosecond on the scale of Earth history, and humans and dinosaurs (with the exception of birds) never lived together, separated in time by tens of millions of years. Yet, geologically speaking, dinosaurs disappeared quite recently. Gazing further back into deep time, Earth has persisted for billions of years, with dinosaurs inhabiting the planet for only a tiny (and relatively recent) fraction of that inconceivable duration. For us, a thousand years seems like an eternity, and it is virtually impossible to conceive the billions of years of Earth history. Placed within the context of the Great Story, the Mesozoic world of dinosaurs encourages us to imagine time differently, and thus to experience our present reality in new ways.

Another essential element of the Great Story is deep connections, including those forged through common ancestry (evolution) and the continuous flow of matter and energy (ecology). All life-forms at any given time are connected in vast webs of relationships that together encompass the biosphere; all of these webs are interwoven with those of earlier times and those of the future. Life in a contingent world means that whatever comes before affects everything that follows. Interconnections run so deep that change in one aspect can have cascading (and sometimes dramatic and unanticipated) impacts on many others. Dinosaurs can help us grasp this notion.

Teaching about dinosaurs is typically conducted as if they have no connection to our modern world, almost as if we are talking about strange creatures from another planet. At most, we inform students that the extinction of dinosaurs 65.5 million years ago cleared the way for mammals and, ultimately, the origin of humans. Had the asteroid missed and dinosaurs not gone extinct, so the argument goes, there would have been no diversification of large mammals—no whales, no elephants, no antelope, no primates, and no humans. I regard this contention as accurate but grossly insufficient, because it completely ignores life’s interconnectedness. By implication, the paths of dinosaurs and mammals are unrelated; one group exits the stage and another enters the scene to continue the drama.

Yet dinosaurs persisted for 160 million years prior to the K-T extinction, coevolving in intricate organic webs with plants, bacteria, fungi, and algae, as well as other animals, including mammals. Together these Mesozoic life-forms influenced the origins and fates of one another and all species that followed. Flowering plants first evolved in the Early Cretaceous and underwent their initial florescence alongside a variety of dinosaurian herbivores. The key issue, then, is not simply the dinosaur extinction but the intertwining of global ecosystems through time. Had the disappearance of dinosaurs occurred earlier or later, or had dinosaurs never evolved, subsequent life-forms would have been wholly different, and we almost certainly wouldn’t be here. In short, we owe as much to the dinosaurs’ lives as we do to their deaths. Much the same could be said for almost any major group of life-forms.

How, then, might the dinosaur odyssey help us communicate the Great Story and achieve the lofty goals of sustainability education? There are many possibilities, and I will highlight just one here.

Birds are common, diverse, and a joy to watch. Their recently revealed status as feathered dinosaurs also prompts an entirely new perspective. I’m picturing an Audubon Society-sponsored “Christmas dinosaur count.” Or better yet, imagine a nationwide “Backyard Dinosaurs” initiative, with the goal of getting kids outside to observe local birds. The tools necessary for this effort—for example, binoculars, bird feeders, and birdhouses—are relatively inexpensive and easily accessible. Kids (and parents) would learn to identify many birds that live around their schools and homes year-round, as well as migratory winged visitors. For youngsters, Tyrannosaurus rex and other ancient monsters would become intertwined with various modern “dinosaurs” like Turdus migratorius (American robin), Corvus corax (common raven), and Buteo jamaicensis (red-tailed hawk). Curriculum surrounding Backyard Dinosaurs might span a range of topics, but should be built on the duo of evolution and ecology. With regard to evolution, emphasis would be placed on the ancestor-descendant relationship with dinosaurs, including the place of birds within the larger epic of evolution. As for ecology, kids would learn about the roles birds play in local ecosystems— from plant eaters and pollinators to predators and prey—as well as their links to other animal and plant species.

In most areas, teachers and parents interested in backyard dinosaurs could find local support through national history museums, zoos, aviaries, and/or birdwatching groups. There might even be opportunities to team up with regional or national “citizen science” programs, designed to get laypeople participating in actual, hands-on scientific research. For example, parents and teachers could have children collect data on species identifications and counts of individual birds, which would then be added to a national, online database. The resulting information might then be used, for example, to track the effects of global warming on bird populations. Believe it or not, research programs like this are already well underway.2 Bird-watching could also be a catalyst for service-learning efforts such as reclaiming watersheds, planting trees that attract birds and other animals, and raising awareness of endangered species and habitats. A vibrant Backyard Dinosaurs initiative, in addition to fostering nature literacy, would help build lasting human-nature connections and a stronger sense of place.

So how about it? Ready to start a backyard dinosaur revolution?

In wrapping up this epilogue, I return to the place where this journey began—the island of Madagascar. Here we will find an even more concrete example of how dinosaurs and paleontology can serve people living today.

Chapter 1 detailed some of the amazing discoveries of Late Cretaceous dinosaurs and other vertebrates made on the Red Island during the past 15 years—from predators like tinyarmed Majungasaurus and buck-toothed Masiakasaurus to herbivores such as the long-necked giant Rapetosaurus and the pug-faced crocodile Simosuchus. These finds and many more are the result of nine field expeditions (so far) led by David Krause of Stony Brook University to a tiny pocket of grassy badlands in northwestern Madagascar. I had the honor of participating in five of those expeditions. The project forever changed the course of my career and those of many others, students and professionals alike.

When working in Madagascar, we camp at the same site on the edge of tiny Berivotra village, a mere stone’s throw from some of the one-room huts, with their mud or thatched-grass walls and palm-leaf roofs. We interact daily with the villagers, some of whom visit camp regularly and have become our friends. We’ve watched some children in this remote community grow from toddlers to adulthood, and we’ve been saddened by the premature deaths of others. We have shared in celebrations, deliberations, times of grief, and makeshift games of soccer (football). Berivotra villagers have guided us to promising fossil localities and helped carry the huge, fossil-filled plaster jackets across kilometers of rugged terrain to the nearest road. Always the community has welcomed us warmly, showering our mixed Malagasy–North American crew with broad smiles as we pass by each day on the way to and from our dig sites.

Back in 1995, while digging in some of our first dinosaur quarries, we noticed that village children were coming by regularly to watch us work, obviously curious about the strange vazaha (foreigners) who insanely chose to sit out in the midday sun picking at the chunks of rocklike bone strewn about the landscape and buried just beneath the surface. These bright-eyed, inquisitive youngsters were invariably rail-thin, although many had distended bellies from protein deficiencies, as well as liver- and spleen-enlarging parasites. We would later learn that diarrheal, dental, and respiratory infections are widespread in this and many surrounding communities. Lacking access to clean water, basic hygiene, and antibiotics, these diseases and others—with malaria topping the list—all too often prove fatal. Working with Malagasy interpreters from our crew, we spoke with village adults and found out that the children did not go to school because, well, there was no school.

The situation we found in Berivotra is mimicked over much of Madagascar, one of the poorest nations on Earth. About one-third of the country’s population of 19 million cannot read or write, and literacy rates tend to be lowest in remote areas. Many rural Malagasy grow up without ever visiting a doctor or dentist, exacerbating abysmal health conditions and limiting both life expectancy and quality of life.

When we asked the Berivotra villagers how we might help and repay them for their many kindnesses, they were nearly unanimous in their request for a school. How much would that cost? They humbly requested U.S.$500, enough to cover the cost of a teacher for a full year! We readily agreed and took up a collection, making sure that sufficient funds were also available for books and supplies. It was decided that the nearby tin-walled church, the only sizeable structure in the community, would be used as the classroom. This simple act was the beginning of what would become the Madagascar Ankizy Fund, a nonprofit organization based out of Stony Brook University with the mission of providing education and health care to children (ankizy in the Malagasy language) in remote areas of the island.3 The Ankizy Fund would eventually build a new school building in Berivotra, dig eight wells for fresh water, provide health care in the form of medical and dental teams, and initiate an arts and crafts “paleo-tourist” industry (with dinosaurs as a main theme). The latter was critical because many villagers were nearing starvation; the economics of the village revolved around the sale of charcoal, based on cutting down trees. But, though the village was literally inside the forest only 50 years ago, the trees have been cut back so far that it is now a 2-day walk to get there.

Today, all the children of Berivotra attend school, and, with assistance from the Ankizy Fund, many have gone on to a secondary school in the nearby city of Marovoay. It is a joy to see them learning and in better health, so proud to be able to read and write. The Ankizy Fund has also expanded its efforts to target other rural communities in Madagascar, thus far funding four new schools, renovating an orphanage, initiating large-scale parasite disinfection programs, and bringing dental and health care to a number of remote areas. Funds have also been acquired to build a medical clinic in a remote village. Community-wide education programs have addressed key issues surrounding nutrition, hygiene, and sexual health.

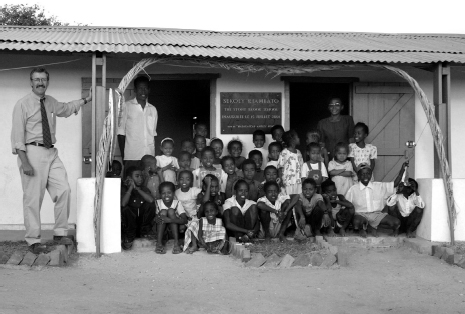

FIGURE EP.1 David Krause (left) stands with the first group of students to attend the newly built Sikoly Riambato (Stony Brook) school, in the village of Berivotra, northwestern Madagascar.

Numerous people in North America and Madagascar have been involved in these efforts—scientists, dentists, doctors, students, and volunteers among them. Funding has come from a variety of sources; most inspiring are the American grade school children who have conducted school fund-raisers, learning in the process about their counterparts on a Third World island and also that they can make a meaningful difference. As with many philanthropic efforts, however, one person has spearheaded the organization, serving as its heart, soul, and brains. In this case, that person is David Krause, the lead paleontologist on the Madagascar project. Krause has made Madagascar the core of his professional life, attempting to split his time between paleontological research and the Ankizy Fund (with the latter usually coming out ahead). As with any humanitarian effort in a developing country, the Ankizy Fund has encountered a number of unexpected pitfalls, but it has persevered through these challenges to make a tremendous difference in the lives of thousands of people in rural Madagascar.

Paleontologists regularly travel to underdeveloped countries like Madagascar in search of fossils. And many other academic disciplines include work in developing countries. Yet all too rarely do these international projects include a meaningful humanitarian component. Indeed, the Ankizy Fund is one of the only examples I am aware of—science with a social conscience. Here, then, is another way that paleontology has the potential to benefit people, in this case directly and immediately. I hope that many other scientists working internationally elect to make the same commitment that David Krause has in Madagascar.