The striking Illustrated London News depiction of the Princess Alice disaster is reproduced in colour on a W. H. Wills’s (Celebrated Ships No. 50) cigarette card, 1911

Leaflet advertising the refurbished Crossness Sewerage Treatment Works. Due to its magnificent Victorian ironwork the engine house has been dubbed ‘the Crossness Cathedral’

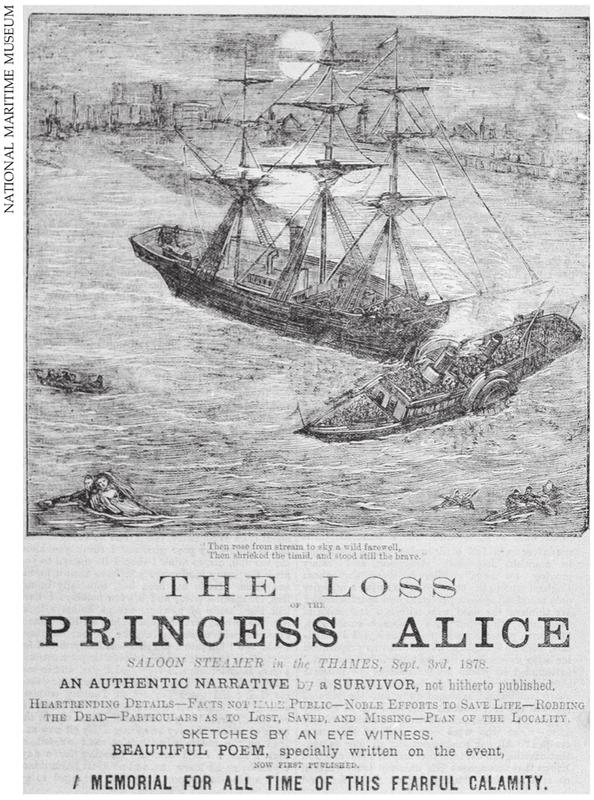

Typical contemporary broadsheet describing and illustrating the Princess Alice disaster

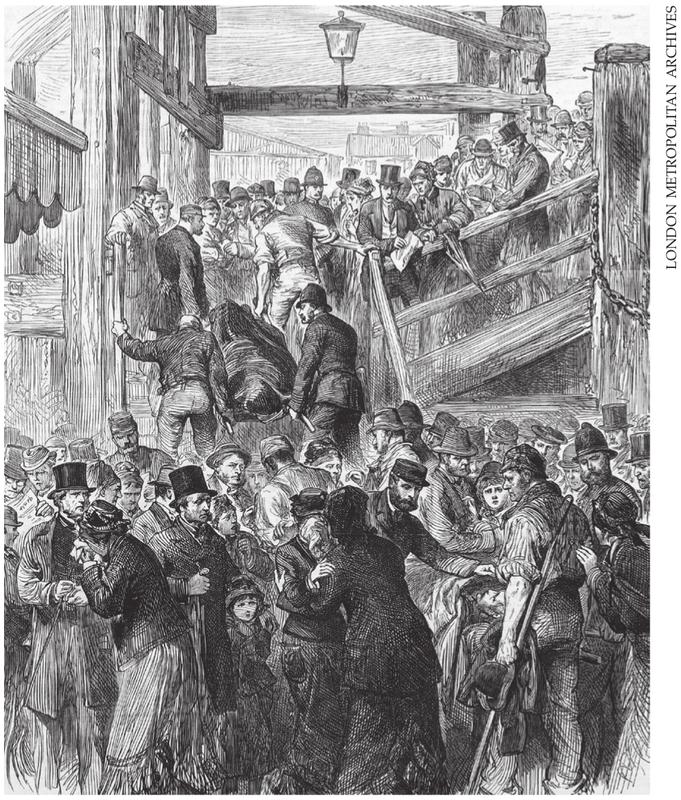

Frantic crowds gather and overwhelm the police on duty at Woolwich Pier where many of the bodies of Princess Alice passengers were brought ashore

There is fierce competition among the swarms of watermen probing the river to encourage the drowned to rise so that they may claim a fee for each body

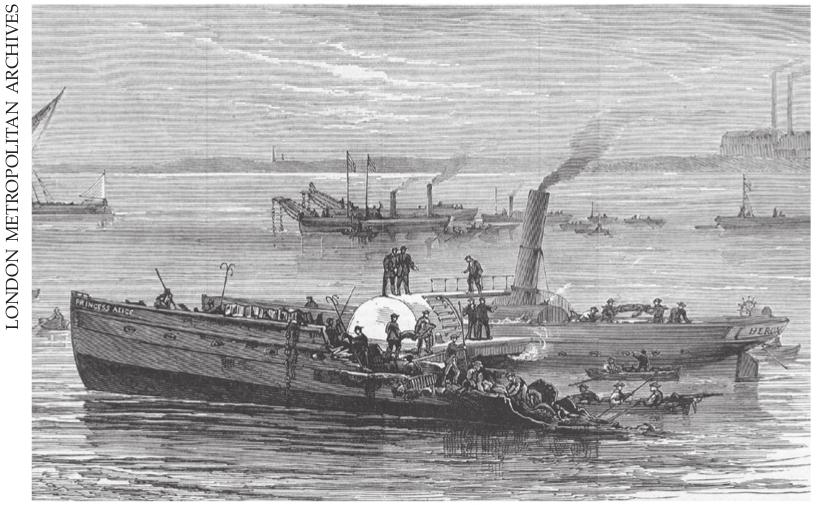

With the aid of divers and heavy lifting chains, three days after the sinking, the forward part of the Princess Alice is brought to the surface and towed to the south shore

Relatives identifying the bodies of the victims at Woolwich dockyard. Initially, bodies found on the northern (Essex) banks of the river could not be held at Woolwich since it was unlawful law to move them to another jurisdiction

Just prior to the collision the huge hull of the Tyne collier, Bywell Castle, looms over the much more fragile pleasure steamer the Princess Alice, while the ships’ warning whistles continue to shriek and the passengers scream

Burying the unknown dead. Eventually, due to increasing decomposition, it became imperative to bury even those who remained unidentified. Their dramatic mass funeral took place on ‘Burial Monday’, 9 September 1878, at Woolwich Cemetery

For almost two weeks, at Woolwich Town Hall, the coroner and his nineteen-man inquest jury listened to a constant flow of relatives and friends identifying the bodies of their loved ones. Only then began the prolonged process of investigating the cause of the accident

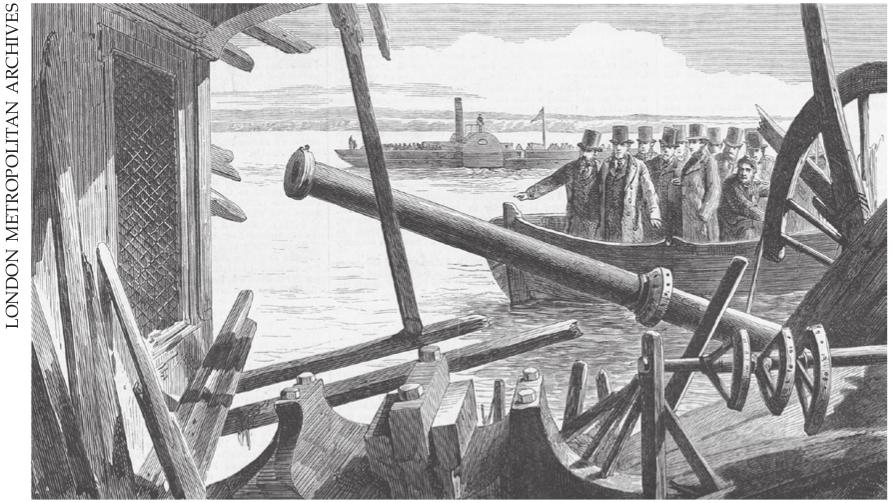

At the start of each day the coroner took his jury to view the latest bodies retrieved and they were also taken to examine parts of the newly-raised wreck

The heavier back-end of the Princess Alice proved more difficult to raise. More bodies were released from the wreck as it finally surfaced on the fifth day after the collision

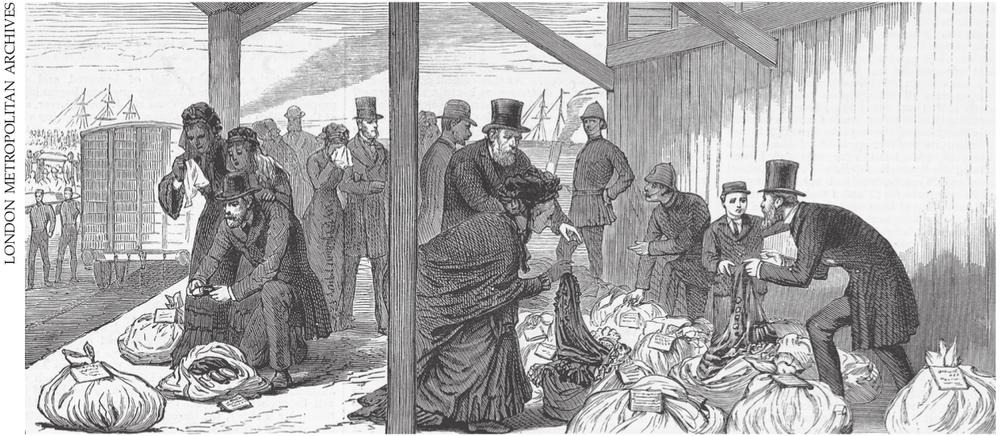

Relatives identifying the belongings of the dead. The number attached to each object corresponded with that placed on the victim’s body: a process designed to make identification easier

The Bywell Castle was a powerful, iron-built, 890-ton Tyne collier. The ship’s most regular coal run took it to the Eastern Mediterranean

The Princess Alice pleasure steamer, built at Greenock in 1865, was only 219 feet long, 20 feet wide and weighed a mere 250 tons

Thames police officers searching for bodies in the drained interior of the forward part of the Princess Alice wreck. None were found among the debris of hats, umbrellas, souvenirs and stewards’ money bags

Identifying the clothes of the dead at Woolwich dockyard. Even when a victim was ‘buried unknown’ their clothing was boiled and retained to aid possible identification later

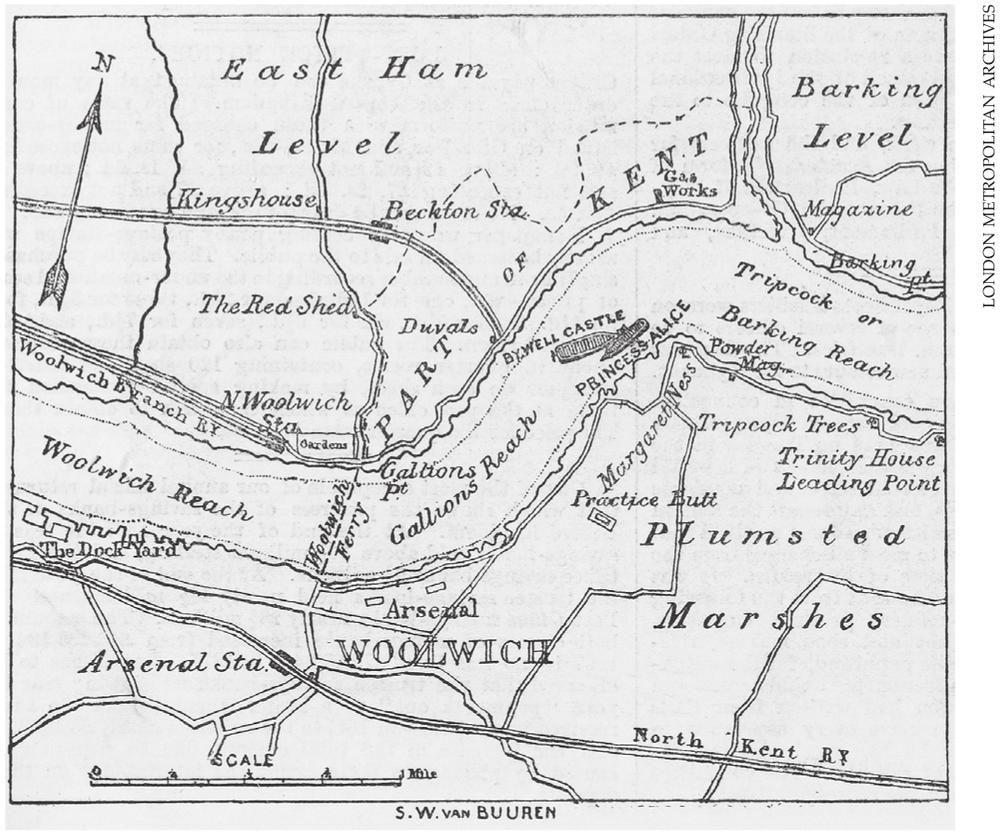

An Illustrated London News map indicating the presumed site of the collision – close by Tripcock Point. Subsequently, there was to be much dispute amongst the witnesses and ship owners about the exact site of the accident

William Grinstead, the 47-year-old captain of the Princess Alice, was considered to be one of the London Steamboat Company’s most experienced and careful employees and also a very nice man

Princess Alice and her family in 1876. Her ill-fated daughter, May, is seen here in her father’s arms

Postcard of the Victorian panel of the Greenwich Millennium Embroideries. The Princess Alice disaster is shown top right