2

WITH THE BEATLES

Second album and fifth single

November–December 1963

Programme for the Beatles’ tour of August 1963, now top of the bill, promoted by Arthur Howes.

The Beatles had hardly been to London until 1963, and then only on a handful of visits, but in the summer of 1963 Brian found them a rented flat in Mayfair where they had a bedroom each, for when they were staying in the capital–though John and Cynthia, having a baby, had a flat on their own in Kensington, directly above Robert Freeman, the photographer.

In April 1963 Paul met a seventeen-year-old actress called Jane Asher through a BBC programme and then in a photo-shoot for the Radio Times. They became friends and he started hanging around her house–eventually moving into an attic room in her family home in November 1963.

It was a huge cultural and social and artistic shock for Paul. Shock is perhaps the wrong word; ‘sensation’ would be better, as Paul was impressed, fascinated and stimulated by the middle-class, bohemian, artistic Asher household and absolutely loved being a part of it. Having been brought up on a Liverpool council estate, he had no experience of such a life and such a home. This is not to suggest that his father was rough or uncultured; Jim was well dressed, charming, socially at ease in most company–like Paul himself–but their house was small, money was short, books and amenities few.

The Ashers lived in a large, rambling Georgian terrace at 57 Wimpole Street, traditionally London’s medical area, but also with literary associations (Elizabeth Barrett Browning had lived a few doors along at number 50). Jane’s mother was a professor of music and her father an eminent doctor. They were cultured, intellectual, and encouraged their children to be creative and express themselves. Their house was filled with paintings, books and scientific journals.

Paul lived there as a lodger, very simply, for around two years, which is surprising, when he was suddenly making so much money. He could have afforded a posh house of his own, out in the suburbs, which is what John, Ringo and George all opted for. But he loved Jane and the Ashers, their lifestyle, their friends. Being in central London meant he was handy for avant-garde galleries and exhibitions–and the night clubs–with no need for a long trail back home afterwards.

The influence of this new social and cultural world in which Paul was moving soon began to have an effect on his writing. But he wasn’t the only one open to new experiences; once they moved to London, John and George began broadening their horizons too. They were not intellectually intimidated by the new circles in which they found themselves–after all, the Beatles weren’t the stereotypical overnight pop sensations who had left school at fifteen to become lorry drivers or labourers before hitting the big time. John, Paul and George had gone to excellent grammar schools, which meant they had to be clever enough to pass the entrance exams, and though they may have disliked school at the time, it had exposed them to Chaucer and Shakespeare as well as modern art and literature.

When they weren’t in London they were rushing round the UK on tours, or doing TV and radio appearances, but in the summer of 1963 they managed to find time to start work on their second album, With the Beatles, which eventually came out in November of that year, just eight months after their first album.

The recording sessions were spread over three months, as opposed to one day for Please Please Me, but this was due to their busy schedule. Double-tracking was now standard, so the sound is better and stronger, but once again only half the fourteen tracks were composed by them.

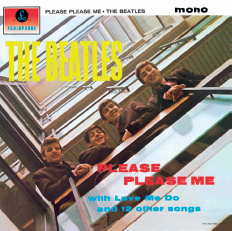

The cover of the first album had featured a snap of them standing on a staircase at EMI’s London offices in Manchester Square, wearing inane smiles, as if in a school photograph–you can almost hear the photographer* shouting, ‘Cheese!’ For their second album, they wanted a much artier photograph. They had always admired the portrait of Stu Sutcliffe that Astrid Kirchherr had taken in Hamburg, with its dramatic half-light and half-shadow, but she had not photographed all the Beatles. So Robert Freeman was commissioned to do similar shot featuring all four of them. The result, shot in a hotel in Bournemouth, makes them look serious and sombre, and it was so successful that for a while Freeman became their official photographer.

On both albums, press officer Tony Barrow wrote the sleeve notes in the breathless style that typified early sixties pop prose. ‘Pop picking is a fast n’ furious business these days’, runs his first sentence on Please Please Me. He describes Paul and John as the band’s ‘built in tunesmith team’ and quotes one radio presenter as declaring that they are ‘musically the most exciting and accomplished group to emerge since The Shadows’. By the second album, they are being hailed not only as ‘remarkably talented tunesmiths’ but also ‘cellar stompers of Liverpool… sure-fire stage show favourites… rip roarin’… fabulous foursome…’

The second album was made up of yet more love songs, happy or otherwise, still following the traditional pop format, but the interesting development was that at long last, after recording twelve of their own songs (plus twelve by other composers), young George was finally allowed to have one of his own compositions included on the album.

It Won’t Be Long

Written by John, and recorded as a single to follow ‘She Loves You’. They decided it wasn’t up to it, so used it to kick off the new LP instead. And it isn’t up to much, really, though the title leads into a nice play on words: ‘It won’t be long, yeah yeah–till I belong.’ Not belonging fits the mood of the song, but neither the tune nor the words develop or have an obvious hook to make the song lodge in your brain. Another one-dimensional song–about a one-dimensional problem: someone at home, waiting for their lover, dejected and rejected, though we don’t know why.

You could of course read into it that John’s rejection was not caused by some unknown girlfriend but by his own parents, who abandoned him at the age of five to be brought up by his aunt. When his mother did eventually reappear in his life, she was cruelly taken away from him–killed in a traffic accident. Perhaps this is why he feels that the world is against him. Seen in this light, the lyrics can be read as a genuine cry of anguish.

The characters of John and Paul are forever being contrasted, with Paul typified as the happy, cheerful, optimistic one, and John the tortured soul, thanks to his troubled background. But Paul had his own traumas, most notably the loss of his mother at a young age, so why did that not make him a misery guts? Or did the loss make him determined to overcome such a blow by putting on a cheerful front?

Despite losing his mother, Paul was brought up in a happy family, with a loving caring constant father. John, regardless of things he said later, also had a happy childhood, at least until he was about twelve, and was lovingly and well cared for. It was as a teenager that he rebelled against school and teachers and the strict, unbending Aunt Mimi, maintaining he wasn’t really loved and his genius not recognized.

Paul and John are indeed very different characters, and this difference, as the years went on, was reflected in their songs, but I find it hard to agree that it was circumstances that made them the way they were and formed their general outlook on life. I prefer to think that that was how each was born, though it took a while for their innate differences to emerge.

All I’ve Got To Do

John wrote this in 1961, at a time when he was trying to sound like Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, so he is attempting his sweetest, smoothest voice and nicest harmonies. It ends on a few bars of humming, which doesn’t sound much like him. One can imagine him laughing at himself as he did it. The words are equally unoriginal: ‘Whisper in your ear, the words you want to hear.’ There is a reference to ‘calling on the phone’, which enforces the American influence–as few people in Britain had telephones.

All My Loving

Another love song, this time by Paul, and probably the best love song they had produced to date. The words are fairly conventional, sending all his love to someone who is away, promising he will always be true, rhyming ‘kissing’ with ‘missing’, ‘you’ and ‘true’, but it rings sincere and genuine. It’s the tune that really makes it, the first four bars being especially haunting. So it’s strange that, according to Paul himself, it all began with the words and not the tune. ‘It was the first song I ever wrote where I had the words before the music.’ They came to him while shaving, and he wrote the words down as a poem.

The girl he was missing was Jane Asher, his new London girlfriend.

Paul with Jane Asher, to whom he got engaged on Christmas Day, 1967.

Don’t Bother Me

This is the first George song–though not all Beatles fans registered how unusual it was to have George singing his own song. I certainly didn’t, assuming at the time it was another Lennon–McCartney composition. This was partly because it didn’t lead to a spate of George songs–that came very much later–so it was easy to forget it had ever happened.

George wrote it in August 1963 while on tour, at the Palace Court Hotel in Bournemouth where Robert Freeman shot the cover photo. George had fallen ill, and was recovering by staying in bed, so decided to try and write a song, just to see if he could do it. It was the first song with lyrics he had ever written on his own. In 1967, when I was doing the biography, George was dismissive about it: ‘It was a fairly crappy song. I forgot about it completely once it was on the album.’ He said he gave up all thought of writing songs for another two years–he was too involved with other things.

In his memoirs I Me Mine, published in 1980, he repeated the assertion that it wasn’t much of a song, ‘It might not even be a song at all, but it showed me that all I needed to do was keep writing and then eventually I would write something good.’

Perhaps the lyrics suggested themselves because at the time he wrote the song he did not want to be bothered, by anyone, as he was feeling poorly, but he turns it into a love song. He is missing his love, who has left him all alone, so please keep away. The sex of the person bothering him is not stated–one assumes it began with one of the other Beatles knocking on his bedroom door–but in the lyrics it sounds as if it could have been a girl who was after him.

Bill Harry, editor of Mersey Beat, has another theory. Whenever they met in Liverpool, Bill would ask George if he was going to compose another instrumental like ‘Cry for a Shadow’, the tune he had co-written back in 1961. George’s response would always be, ‘Don’t bother me.’ According to Bill, George later told him that this phrase had lodged in his mind–and that he had turned it into a song. The phrase certainly sounds typical of George. He could be very serious, concentrating hard on whatever he was doing, and didn’t like being interrupted or asked idiot questions.

It’s a good song, as good as anything the Beatles had written up to that time, which was why I had assumed it was a Lennon–McCartney composition. George’s voice gets a bit low at times, till you fear he will hit the floor. It has a vaguely Latin American rhythm, with Ringo on bongo and drums, which trundles it along.

The manuscript is in George’s hand, without any changes or corrections, so it was presumably written out neatly at some stage. George’s hand looks young and hesitant, rather childlike compared with the bolder handwriting of Paul and John, as if perhaps he was not used to writing stuff down. Which was roughly the case. John had been writing reams of poems and stories as well as songs since about the age of ten; likewise Paul had written hundreds of songs. George, despite having gone to the same grammar school as Paul, had not knuckled down to his essays and schoolwork, abandoning sixth form and A levels by leaving at sixteen to take on a fairly menial job. ‘Don’t Bother Me’ was written at a time when he felt he couldn’t write lyrics, unlike the fab two.

‘Don’t Bother Me’, George’s first composition, in George’s handwriting–released on the LP With The Beatles, December 1963.

Since she’s been gone I want no one to talk to me.

It’s not the same but I’m to blame, it’s plain to see.

So–go away, leave me alone, don’t bother me.

I can’t believe that she would leave me on my own.

It’s just not right when every night I’m all alone.

I’ve got no time for you right now, don’t bother me.

I know I’ll never be the same if I don’t get her back again.

Because I know she’ll always be the only girl for me.

But ’till she’s here, please don’t come near, just stay away.

I’ll let you know when she’s come home. Until that day,

Don’t come around, leave me alone, don’t bother me.

Don’t bother me.

Little Child

A sad and lonely boy wants someone to dance with him–it sounds very much like John, but the song was a joint effort. Why though would he be asking a little child to dance with him? Did it really mean a child, as in some sort of game, or did it mean a young girl, a babe, with whom he was going to have some teenage fun? You wouldn’t get away with such a title today.

The song follows a pattern set by other Beatles songs–particularly in the repetition of ‘come, come on, come on’ and ‘feel so fine’, and of course the harmonica, with John playing quite an extensive solo. It was supposedly written with Ringo in mind, for him to sing, as it was a simple song, then John decided to sing it himself.

The manuscript would appear to be an early version, written in Paul’s hand. It varies slightly from the finished version; the line which became ‘If you want someone to make you feel so fine’ was originally ‘If you want someone to have a ravin time’ (though in writing it out he has missed out the word want). The word ‘ravin’ does rather jar, and doesn’t fit in with the notion of a little child, which probably explains why it was dropped.

The terminology Paul has used is quite interesting. He describes the first bit as the chorus (rather than writing it out, he simply puts ‘chorus’); then we have two verses, although rather than use the word ‘verse’ he numbers the two sets of five lines as 1 and 2–with the chorus in the middle and then the chorus again at the end.

Wilfrid Mellers, in his analysis of Beatles songs, described their typical song pattern as ‘Edenic’–by which he meant they began with the Verse, consisting of four or five lines, then the melody was reprised with another set of words, which Mellors termed the Repeat. This was followed by the Middle, before ending with the Da Capo, which I take to be another repeat of the Verse. It does seem to complicate a simple song, and Paul’s divisions between Chorus and Verse are perfectly adequate. As their songwriting progressed from a simple repetition of chorus, verse, chorus, they began to elaborate on the basic formula.

When the Beatles referred to the ‘middle’ or the ‘middle eight’, they meant the middle section, the development of the tune, and some new words, before they repeated the beginning. This was often the hardest part to write. Getting the beginning–the initial theme, in words and music–often came to them quite quickly, but they tended to struggle with the next bit. Particularly John, who would often leave songs unfinished, undeveloped, because he was stymied by the middle bit.

John and Paul had come to songwriting with no knowledge of how others had done it. Their approach was simply to study songs they liked, breaking them down into components, and then copy the format. Since they couldn’t read music they were incapable of transcribing the notation, but they got round that obstacle by jotting down the chords, for example G D E, to remind themselves how they had played it.

In this example, the progression of a chorus (which is actually repeated twice on the record) followed by a verse, chorus, verse, chorus, follows one of the traditional patterns of composition.