8

STRAWBERRY FIELDS FOREVER

February 1967

I went to see Brian Epstein on 26 January 1967, at his Belgravia home, to discuss my plan for a biography of the Beatles, an idea I had first put to Paul the previous month. Paul said I would have to see Brian, but he would help me write a suitable letter. Brian cancelled several times, for reasons I never knew until later.

I remember how elegant and sophisticated he was; so well-dressed, well-spoken, a man of the world. Yet at the time he was just thirty-two–two years older than me. I remember noticing two oil paintings on the wall by L.S. Lowry. But what I remember most about that meeting was ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’.

He had an acetate recording of it–a sort of proof–as the record was not officially released till 17 February. Sitting back in an armchair, arms folded with fatherly pride, he waited as I listened to it.

I was stunned. Could this be the Beatles? My first thought was Stockhausen–not that I knew much about him or his music. The sounds were so avant-garde, futuristic, experimental, multi-layered that it was impossible to take in at one go, least of all the words, so I got him to play it again.

When it finished, I asked what the title meant–and he didn’t know. I asked what the lyrics meant–and he didn’t know that either. He had clearly not been involved in its production, and seemed slightly embarrassed by his ignorance; after all, he was their personal manager, responsible for expertly organizing their career since 1961.

He then played the other side: ‘Penny Lane’. That was much easier to understand and enjoy, and as a Liverpudlian he was familiar with most places.

Afterwards he put the acetate away, saying he could not be too careful. One had already been stolen, for the recording would be worth lot of money to the pirate radio stations. I didn’t believe him–it seemed far-fetched that a pirate station would pay big money, just to get the record a few days ahead of their rivals. I later discovered that one theft of an acetate had been his fault. He had brought home some young man, a sailor–butch not gay–given him drinks and pills and tried to get him into bed. The sailor had then beaten Brian up and left–taking the acetate with him. Overwhelmed by humiliation and guilt, Brian then took more pills and went into a deep depression, cancelling everything for a few days–including two appointments with me–until he could face the world. The Beatles were aware that he was gay, but they knew none of the details of his personal life.

During that first meeting, Brian suggested a clause in the contract neither I nor my agent had mentioned. He said he would give no access to the Beatles to any other writer for two years after my book came out. It came out in October 1968; two years later, in 1970, the Beatles had disbanded. So mine was to be the one and only authorized biography of the Beatles, though I had no idea of it at the time. How lucky was that?

Although I was astounded by ‘Strawberry Fields’, I rather wondered what some of the fans would make of it. It was yet another tremendous leap forward for the Beatles, when they’d already made so many in the last two years. How fortunate I would be–if the book came to pass, if we didn’t all fall out, if the project didn’t get cancelled–to witness firsthand the Beatles at home and in the studio, making more music like this, making yet further progress.

Strawberry Fields Forever

John wrote the song in Spain in September 1966, while filming How I Won the War. Once the touring had stopped, and the public performances were coming to an end, each of them was free to do their own thing until they assembled together in the studio for the next record.

They had been thinking of a concept album about their childhood and Liverpool, as the unused verses of ‘In My Life’ indicated, but it was never completed.

Now, far from home, stuck out in Almeria, John began thinking back to his childhood when he used to visit the nearby Salvation Army home, Strawberry Field (without the s), a gothic mansion with a large overgrown garden. He loved going to the annual fête or breaking in and playing there with his friends Pete Shotton and Ivan Vaughan, climbing the trees, imagining he was in an Alice in Wonderland magic world. ‘As soon as we could hear the Salvation Army band playing,’ so his Aunt Mimi told me, ‘John would jump up and down shouting, “Mimi, come on, we’re going to be late.” ’

His random childhood memories got mixed up and fused with drug-related images and influences–tune in, take you down, nothing is real. John was always conscious of the feelings of displacement and disorientation he had experienced as a child–or told himself he had. He was also aware of his own habit of thinking or saying one thing, then the next moment the opposite, believing it each time. It’s getting hard, but it all works out, it doesn’t matter much, it’s all wrong, I think I know, yes, I think I disagree. Two of the best lines are: ‘Nothing is real and nothing to get hung about’ and ‘Living is easy with eyes closed, misunderstanding all you see.’

The earliest known demo of the sung, done by John on a tape recorder in Almeria, had no chorus and only one verse which began, ‘There’s no one on my wavelength, I mean it’s either too high or too low.’ Wavelength was later changed to tree.

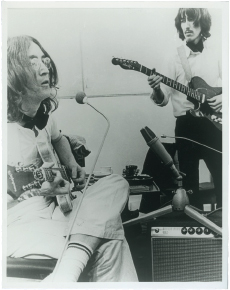

John and George in the Apple studio, 1969.

In 1980, he explained that he had felt different all his life, which is what he was saying with the phrase ‘No one I think is in my tree’. At the same time he felt he was too shy and self-doubting–or a genius. ‘I mean it must be high or low.’ The phrase ‘nothing to get hung about’ suggests not having any hang-ups, but also hanging from a tree possibly, remembering Aunt Mimi telling him not to climb over the wall and play there, and John replying, ‘They can’t hang you for it.’

The song sums up everything about the Beatles at this stage: introspection, disorientation, self-doubt, all wrapped up in beautiful, original, multi-layered, disturbing music. Even if you take away the musical sounds and trimmings, it is still a fine song.

John always considered it one of his best–along with ‘I Am The Walrus’, ‘Help!’, ‘In My Life’ and ‘Across The Universe’. He reckoned the lyrics to all of those were pretty good. ‘The best lyrics stand alone. They don’t have to have a melody.’ John always thought he was a poet. ‘Except I am not educated.’

‘Strawberry Fields’ became the most analysed of all the Beatles songs they had done so far, with the experts attempting to unravel how every sound was made–identifying the trumpets and cellos, maracas and slide guitar, explaining the electronic wizardry and background sounds. It took the Beatles an unprecedented amount of time–fifty-five recording hours in all, spread over five weeks–to get it to their satisfaction: a sign of their power but also their perseverance.

The music press were a bit confused by it. In the New Musical Express on 11 February 1967, Derek Johnson wrote that it was ‘certainly the most unusual and way out single the Beatles have yet produced–both in lyrical content and scoring. I don’t really know what to make of it.’ But he did find it ‘completely fascinating’ and more spellbinding every time he played it.

‘Strawberry Fields’ was their first single since ‘Please Please Me’ in January 1963 not to go straight to number 1 in the UK. It got stuck at number 2–kept out of the top spot by Engelbert Humperdinck’s ‘Release Me’. Ringo said he was relieved–it took away the pressure.

The manuscript, which I believe is the only copy that has ever turned up, given to me by John, has only twelve lines, several of them slightly different from the final version, but you can see his thought process, writing one thing, then commenting on it in his mind, as if thinking, er, I disagree.

I can’t quite make out what that scribbled-out first line was originally, before he inserts ‘I think in my tree’. But it does look like that line he had sung on the tape–‘There’s no one on my wavelength’. At this stage, in these lines, ‘Strawberry Fields’ is not mentioned.