10

MAGICAL MYSTERY TOUR

1967–1968

After the exertions and excitements and success of Sgt. Pepper, they didn’t release another full-length new album for a whole year. Nevertheless they were highly productive when they did get together, working on two film projects (Magical Mystery Tour and then Yellow Submarine) that needed new songs and also a handful of singles.

Magical Mystery Tour was the first and most interesting project, in that it had some good songs and it also looked as if it would take them in a totally new direction. It didn’t quite go to plan, but I remember all the enthusiasm and ideas that went into it and the anticipation and excitement when we were shown it for the first time.

The Beatles decided to throw a private Magical Mystery Tour party for friends and family, which was held at the Royal Lancaster Hotel on 21 December 1967. We had been told to come in costumes, which had me moaning about having to spend money renting clothes. My wife and I went as a Girl Guide and Boy Scout, wearing ill-fitting stuff borrowed from some kids in our street. Everyone else wore really expensive costumes. Paul and Jane Asher came as a Pearly King and Queen and looked ever so loving and sweet. Four days later, on Christmas Day 1967, they announced their engagement. John was dressed as a Teddy Boy and looked menacing in his leather jacket, drainpipe trousers, brothel-creepers with his hair greased back in a duck’s arse (DA, in polite circles). At the same time, he seemed rather distant, switched off, not much interested–which was how he had been during most of the filming. Later he tried to disown the film, saying it was all Paul’s doing, he was just dragged along, which was more or less true.

For a year, they had been putting off doing a third Beatles film, then on a flight back from the USA with Jane, Paul came up with the idea of doing an hour-long TV film in which they would all get on a bus, shoot stuff, see what happens. It would be mysterious in as much as no one would know where they were going. And magical, in that they could do whatever they wanted.

The ‘Mystery Tour’ notion harked back to their childhood; in the fifties, few working-class families had a car, so bus and train companies would run excursions to popular destinations, sometimes keeping the destination secret to add to the excitement. Growing up in Carlisle, as I did, you always ended up in the Lake District, so it was never much of a mystery. It was still a good day out though; the dads would take a crate of beer on board and everyone would sing on the way home.

The other element in Paul’s mind, which sparked off the idea, was hearing about a group of West Coast hippies, led by author Ken Kesey, who toured in a psychedelically painted coach.

Having come up with the idea, another six months went by before Paul began to flesh it out, by which time Brian Epstein was dead. With no manager to calm them down or provide back-up, they set off on the jaunt with little planning, no real script, taking along some character actors whom they admired (there were no auditions; they simply invited them to come along).

Paul, in his naïvety, thought they could just turn up at Shepperton Studios to shoot the big scenes–not realizing such places have to be booked months if not years in advance. In the end, they had to mock it up in an old airfield in Kent.

When it came to the editing, Paul set aside two weeks–but in the event it took eleven, hacking ten hours of film down to sixty minutes.

I used to visit him in an editing studio in Old Compton Street, Soho, up some stairs above a dodgy club. Outside there was often a drunken old tramp with carnations behind his ears who did a funny dance on the pavement. Paul was amused and would invite him upstairs–which led to more delays as they couldn’t get rid of him. His party piece was ‘Bless ’Em All’, with obscene words substituted.

At the time, watching Paul directing the film–which in essence he did–and then editing it, I thought it amazing that this young lad, with no training in film technique, was working it all out for himself, doing it his way. They’d done the same thing with music: composing songs without being able to read or write a note of music, and making records before they had any studio experience. This was their philosophy: you could do these things, if you really wanted. There was no need to follow the rules or be bossed around. A very modern concept. Of course, it helped that by this time they were multimillionaires who had already made their mark in the music business.

The film was sold to the BBC for £10,000 and broadcast on Boxing Day, shoe-horned between a Petula Clark show and a Norman Wisdom film. It was well and truly slaughtered by the critics. The Daily Express declared it ‘blatant rubbish’. Paul went on The David Frost Show next day to apologize, saying he had goofed, which I thought was slightly craven.

I think one reason for the criticism was that, after five years of Beatlemania, worldwide adulation, being hailed as the best-known people on the planet, bla-bla, many in the media were looking for a chance to take them down a peg or two, especially when they appeared to be condoning drugs.

They should have worked harder on the script beforehand, planned all the scenes in advance, but the idea was to make it spontaneous, provide family amusement over the festive season. As a Beatles fan, then and now, I enjoyed it. It was a modest, short film, done on a budget. I couldn’t see why the clever-clogs critics were so beastly.

The BBC’s internal Audience Research Report for Tuesday, 26 December 1967 reported that 25 per cent of the population of the UK had watched it–but alas the majority had not enjoyed it. Comments from viewers included: ‘The biggest waste of public money since the Ground Nut Scheme’, ‘A load of RUBBISH. We have made better home movies ourselves’, ‘I found it unspeakably tiresome and not the least bit funny–but perhaps this is “sick” humour in which case I am emphatically not “with it”.’ However, the songs were said to be the only redeeming feature.

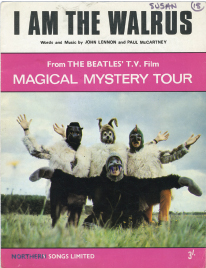

The songs, such as ‘I Am The Walrus’, have survived the test of time (despite Russell Brand mucking it up at the 2012 London Olympics). The way the songs were shot as self-contained little rock videos was ahead of its time. Over the decades, the film has acquired a bit of a cult following. It has improved with age, as we all do, tra la…

Magical Mystery Tour

Six of the numbers from the film came out in the UK as a double EP, which was accompanied by a twenty-eight-page booklet with stills from the film, the lyrics of five* of the songs and a synopsis of the plot, written and drawn as a children’s comic. It was a neat little production.

‘Magical Mystery Tour’, the introductory number, didn’t really have much in the way of lyrics. More a list of clichés and exhortations, inviting punters to join the tour. And that was how the lyrics were first written, with Paul asking anyone around to shout out likely lines. They had tried to buy some mystery tour posters, so they could get the genuine words, but when Mal Evans was sent out on an expedition to find some, he came back empty-handed. It seemed there weren’t any mystery bus tours any more, at least in London and the South. So this first track is really just a list, telling you to roll up, make a reservation, satisfaction guaranteed, with Sergeant Pepper-type brass band music. I described the recording of the song in the biography.

Your Mother Should Know

Having recorded the introductory song, they then took a break for about four months, before recording the second track. This one doesn’t have much in the way of lyrics either, apart from inviting everyone to get up and dance to a song your mother should know. Musically, there is no middle eight, the whole thing consists of a chorus–and very nice it is too, a pastiche of the sort of songs Paul’s family used to sing and dance to around the piano at Christmas time. It looked good in the accompanying film with the four Beatles in white suits descending a staircase to be joined by a team of dancers. Even John seemed to be enjoying himself.

Paul wrote it in Cavendish Avenue at a time when some of his relations were staying with him, playing it on a harmonium while they listened in the next room. It’s Paul having one foot in real life, able to be psychedelic and multi-layered and use Indian instruments, and the other foot in the past, able to commune with all generations.

I Am The Walrus

John’s contribution to Magical Mystery Tour could not be more different–another of the stream-of-consciousness nonsense he wrote in his poems and letters, stuff that he never thought, back in 1962, he would ever get away with in a pop song. And yet it is in some ways just as nostalgic as Paul’s efforts.

Many of the lines are straight pinches from his childhood, all of them still totally familiar to me, though probably not to most people under the age of fifty. In British school playgrounds in the fifties, we used to recite a poem that went ‘yellow matter custard’; another playground favourite was ‘umpa umpa, stick it up your jumpa’, which John can be heard chanting at the end of the song. Other influences are clearly Edward Lear’s nonsense and Alice in Wonderland.

I was with John when the first stirrings of the song came to him. It was the day I arrived to find he wasn’t talking, but while we were swimming in the pool the sound of a police car sparked off a rhythm in his head. He later started putting words to the rythmn: ‘Mist-er Cit-ee police-man sitting pretty’. In 1968 he told interviewer Jonathan Cott about it: ‘I had this idea of doing a song that was a police siren, but it didn’t work in the end [sings like a siren] ‘I-am-he-as-you-are-he-as…’ You couldn’t really sing the police siren.’

He ended up with three scraps of songs which were eventually put together and the lyrics completed. According to Pete Shotton, it was the arrival of a letter from Quarry Bank schoolboy Stephen Bailey telling him that the lyrics to Sgt. Pepper were now being analysed by school teachers and academics, that prompted John to include some of the dafter phrases in ‘I Am The Walrus’: ‘Let the fuckers work that one out’ so he said to Pete.

The words have indeed been heavily analysed over the years. The reference to pigs in a sty has led some to interpret it as an anti-capitalist rant, which John said was never his intention. Others have claimed it is anti-education, because he mocks the ‘expert texperts’ who made snide remarks while he was crying by asking who is the joker now, i.e. who’s having the last laugh. That was one of John’s pet themes: he always felt his teachers were against him and did not recognize his brilliance.

But even nonsense words have to come from somewhere, there must have been a thought process that threw them up. John admitted that he was thinking of Allen Ginsberg when he wrote ‘elementary penguin singing Hare Krishna’, as Ginsberg used to chant it at his performances.

While John was working on the final version, before going into the recording studio, I misheard the line ‘waiting for the man to come’. It sounded to me like ‘waiting for the van to come’, which I told him was a phrase from my school days, when someone thought to be potty or mad would be told that a van would come and take them away. John liked the image and so changed man into van.

Some words are made up, such as crabalocker, which sounds connected with fishwife. I like the idea ‘how they snied’; was he picturing pigs making snide comments? Semolina and pilchards were foods from the fifties that we all hated.

The walrus came from Lewis Carroll’s ‘The Walrus and the Carpenter’–though John at the time had not realized that the walrus was the bad guy, so it should have been ‘I am the carpenter’.

I only recently heard of a possible explanation for the eggmen. Eric Burdon, leader of the Animals, with whom John had shared a few wild parties, supposedly enjoyed breaking an egg on the naked body of a girl.

The music caught the surrealist feeling of the words, with a swirling crescendo of sounds, from rock to classical orchestra music, a chorus of backing singers and backdrop of people talking.

The manuscript, in John’s hand, has some changes: ‘pornographic policeman’ became’ pornographic priestess’, ‘through a dead dog’s eye’ became ‘from a dead dog’s eye’ and ‘you been a lucky girl, you let your knickers down’ became ‘you been a naughty girl’. It was not officially banned by the BBC, for they allowed the song to be included in the Magical Mystery Tour film, but on November 27th 1967, the Controller of BBC1 issued an internal memo saying it contained “a very offensive passage” and the record itself could not be played on radio or TV, which included programmes such as Top of the Pops and Juke Box Jury. ‘Other possible outlets are similarly blocked off.’

I am he

as you are he

as you are me

and we are all together.

See how they run

like pigs from a gun

see how they fly. I’m crying.

Sitting on a cornflake, waiting for the van to come.

Corporation tee-shirt, stupid bloody Tuesday,

man, you been a naughty boy, you let your face grow long.

I am the eggman, oh, they are the eggmen–

Oh, I am the walrus GOO GOO G’JOOB.

Mr City, policeman sitting pretty little policemen in a row,

see how they fly

like Lucy in the sky

see how they run. I’m crying–I’m crying.

I’m crying–I’m crying.

Yellow matter custard dripping from a dead dog’s eye.

Crabalocker fishwife, pornographic priestess,

Boy, you been a naughty girl you let your knickers down.

I am the eggman, oh, they are the eggmen–

Oh, I am the walrus, GOO GOO G’JOOB.

Sitting in an English garden waiting for the sun,

if the sun don’t come, you get a tan from

standing in the English rain.

I am the eggman, oh, they are the eggmen–

Oh, I am the walrus, G’JOOB, G’GOO, G’JOOB…

Expert texpert choking smokers,

Don’t you think the joker laughs at you? Ha ha ha!

See how they smile

like pigs in a sty,

see how they snied. I’m crying.

Semolina pilchard, climbing up the Eiffel Tower.

Elementary penguin singing Hare Krishna

man, you should have seen them

kicking Edgar Allan Poe.

I am the eggman, oh, they are the eggmen.–

Oh, I am the walrus GOO GOO GOO JOOB

GOO GOO GOO JOOB GOO GOO

GOOOOOOOOOJOOOOOOOOOB.