Dig A Pony

Pure self-indulgence; John was trying to see how far they could make things up as they went along, without preparation. Somewhere inside all the pony, road hog, moon dog nonsense (which John admitted was garbage), and forced rhymes like penetrate, radiate, imitate, indicate, syndicate, there is a half-decent song trying to get out. It surfaces briefly in the two-line chorus where John movingly sings about Yoko: ‘All I want is you / Everything has just got to be like you want it to.’ This suggests that he saw Yoko forever organizing him and their life together–which was roughly true. Paul’s Linda, by comparison, was laidback, let it all hang out, play it by ear, let’s go off and get lost, see what happens–which was also roughly true. This aspect of the character of each of their respective new loves greatly appealed to each of them. John had felt lost and wanted to be led. Paul was fed up with the constraints of being engaged to Jane, and caught up in Apple and the legal problems, being forced to be the leader and boss, as he saw it, in order to get anything done.

The original working title of ‘Dig A Pony’–which doesn’t mean anything–was ‘Con a Lowry’, thought to have been a reference to a make of organ lying around in the studio. I have always wondered if instead it could have anything to do with Brian Epstein’s collection of Lowry paintings (which Brian had bought with the money the Beatles had made for him).

Across The Universe

John’s most poetic lyrics for some time. They appear slightly stream-of-consciousness but are all worked out and make sense, with excellent imagery. Certainly not garbage. ‘Words are flying out like endless rain into a paper cup… pools of sorrow, waves of joy are drifting through my open mind.’

This was a song I heard him struggling with some time early in 1968, perhaps even late 1967, when he was still living at Kenwood with Cynthia, but at the time he only had a few bars and a few lines. In the Playboy interview he said he had been lying in bed next to Cynthia and she had been reproaching him for something. ‘I went downstairs and turned it into a sort of cosmic song rather than an irritated song.’ He had certainly worked hard on it by the time he came to record it in February 1968, then it was later remixed by Phil Spector for the Let It Be album

It was being recorded on a Sunday, when it was difficult to suddenly order up any backing singers, so two of the so-called Apple Scruffs–girl fans who hung around every day outside Paul’s house or the Abbey Road Studios–were called into the studio to help out, a fantasy come true. All they had to do was sing ‘Nothing’s gonna change my world’ over and over again for two hours. One of them was Lizzie Bravo, a sixteen-year-old Brazilian who had been given a trip to London by her parents as a birthday present, then had stayed on, getting a job as an au pair. (She went on to work in Brazil as a singer and publisher, and is now a grandmother, living in Rio–and about to release her memoirs of her time in London.)

I Me Mine

George in his book of the same name tried to tell us what he was saying in this song, but alas I was little wiser. ‘There are two “I’s”: the little “i” and the big “I” i.e. OM, the complete whole, universal consciousness that is void of duality and ego.’ Hmm.

So I went back to the song itself and decided that what he is saying is that there is too much ego in the world–everyone is saying something is mine, it’s I and me all the time. Which is all perfectly true. But how does he know that out there in the void things aren’t much the same–or worse?

If you didn’t have the words written down, it would be hard to work out what George is actually singing. He rolls the three words together, so it comes out as someone’s name–Hymie Mine.

The manuscript in George’s hand is much neater than his normal writing, as if determined to make things really clear to use in his book.

All through the day I me mine, I me mine, I me mine,

All through the night I me mine, I me mine, I me mine,

Now they’re frightened of leaving it,

Everyone’s weaving it,

Coming on strong all the time,

All through the day I me mine.

(Chorus)

All I can hear I me mine, I me mine, I me mine,

Even those tears I me mine, I me mine, I me mine,

No-one’s frightened of playing it,

Everyone’s saying it,

Flowing more freely than wine,

All through your life I me mine.

(Chorus)

‘I Me Mine’, from Let It Be, in George’s ever so nice handwriting.

Dig It

Really silly and pointless lyrics, with made-up words and lists of names out of their heads or out of the newspapers–such as FBI, BBC, Doris Day. All the names and initials are understandable by most people today, except perhaps for Matt Busby, unless you happen to be a British football fan. He was the manager of Manchester United Football Club.

The song, mercifully, is very short, just fifty seconds, and with only six lines, carved out of a much longer jam session. On the album, you can hear them mucking around, as they did in the film, playing up to the cameras, knowing they were being filmed. At the end of this track, John is heard doing stupid voices at Paul’s expense. ‘Now we’d like to do “ ’Ark the Angels Come”,’ he says in a high-pitched Lancashire Wee Georgie Wood voice–introducing the next song, Paul’s serious and heartfelt song about his mother. Not very kind.

Let It Be

In the midst of all the angst and anger, rows and recriminations during this awful year, while Paul was trying to organize them, sort out the problems and frictions–and getting no thanks for it–he was lying awake one night, feeling paranoid, when he imagined that his mother Mary, who died when he was fourteen, was saying to him, Don’t worry, it will turn out OK. ‘I’m not sure if she actually said “Let it be”, but that was the gist. I felt blessed to have that dream.’

Released as a single in March 1970, before the album itself came out, it is far and away the most commercial number on the album.

While it is almost a pastiche of a choral hymn, with lots of biblical overtones and allusions such as ‘hour of darkness’, ‘a light that shines on me’ and of course the image of Mother Mary, it is nonetheless sincere and moving. When Paul has played it over recent years, the hall lights go down and the audience often light candles, cigarette lighters or hold up their mobile phones to shed light. It does then begin to feel almost like a prayer meeting.

You Know My Name (Look Up The Number)

This was the B side of the ‘Let It Be’ single (though not used on the LP), first recorded in 1967 after completing Sgt. Pepper. Again, they were just larking around, stoned a lot of the time, hence its delayed release. It’s a joke song, a comedy number, a Goon Show pop song. The general public will be hard pressed to remember it now, but its origins are interesting, and amusing. The inspiration was typical of many of John’s songs, some of which turned out to be excellent, whose words were taken from other sources, in this case a telephone directory.

The London 1967 phone book with the slogan ‘You have their name? Look up their number’, which inspired John.

John was in Paul’s house, waiting for him to arrive, when he noticed a copy of the London phone book for 1967 lying on the piano. On the front cover was the slogan: ‘You have their name? Look up the number’.

John started playing with the words, and soon came up with a rhythm. Later, in Abbey Road Studios, he told Paul he had a new song, the title of which was ‘You Know My Name, Look Up the Number’. When Paul asked to hear the lyrics–John told him that was it, there were no other words.

In recording it, repeating it over and over like a mad mantra, they ad-libbed some jokey remarks, introducing Paul by saying ‘Welcome to staggers’ and ‘Let’s hear it for Denis O’Bell’. The initial recordings were abandoned, and it was not worked on again until Let It Be–but nobody bothered to tell Denis O’Dell, a producer friend of theirs who had worked at Apple and on A Hard Day’s Night.

When the single came out, O’Dell suddenly received a torrent of late-night phone calls from drugged-up hippies in California. Then groups of people, sometimes as many as ten, started arriving at his door, having tracked down his address, saying they were coming to live with him. He was forced to go ex-directory.

I’ve Got A Feeling

The first side of Let It Be finishes on a burst of ‘Maggie May’, a traditional Liverpool song which they used to perform in their early years. John’s heavy Scouse accent is supposed to be funny but is a bit embarrassing.

Side two begins on ‘I’ve Got A Feeling’, which was originally two songs, one by Paul the other by John, knocked into one–just like in the good old days. They are both in fact good songs.

Paul begins it with the feeling he’s got deep inside; obviously about Linda. John eventually comes in, telling us that everybody had a hard year. Which was true. Apart from all the long-running Apple rows, he had got himself arrested for drug possession and Yoko had a miscarriage. But he tries to keep his chin up, mocking himself in clichés like ‘pull your socks up’, ‘let your hair down’.

After their individual bits, Paul returns with his song while John counterpoints in the background. It ends on a sort of ‘Day In The Life’ crescendo, although not as intense. The lyrics do have some sexual references–such as ‘wet dreams’, and at the end you can hear John saying ‘it’s so hard’–which were not in their early love songs.

One surviving manuscript, in Paul’s hand, is only a scrap, but it gives a snippet of each song. The other is longer, but does not have John’s contribution about their hard year.

‘I’ve Got A Feeling’, from Let It Be, the verses Paul wrote, in Paul’s handwriting.

I’ve got a feeling, a feeling deep inside

Oh yeah, Oh yeah. (that’s right.)

I’ve got a feeling, a feeling I can’t hide

Oh no. no. Oh no! Oh no.

Yeah! Yeah! I’ve got a feeling. Yeah!

Oh please believe me, I’d hate to miss the train

Oh yeah, yeah, oh yeah.

And if you leave me I won’t be late again

Oh no, oh no, oh no.

Yeah Yeah I’ve got a feeling, yeah.

I got a feeling.

All these years I’ve been wandering around,

Wondering how come nobody told me

All that I was looking for was somebody

Who looked like you.

I’ve got a feeling that keeps me on my toes

I’ve got a feeling, I think that everybody knows.

Oh yeah, Oh yeah.

Oh yeah, Oh yeah, Oh yeah.

Yeah! Yeah! I’ve got a feeling. Yeah!

Ev’rybody had a hard year.

Ev’rybody had a good time.

Ev’rybody had a wet dream.

Ev’rybody saw the sunshine.

Oh yeah, Oh yeah. Oh Yeah.

Ev’rybody had a good year.

Ev’rybody let their hair down.

Ev’rybody pulled their socks up. (yeah.)

Ev’rybody put their foot down.

Oh yeah. Yeah!

Oh my soul

Oh it’s so hard

One After 909

Probably the oldest known Lennon–McCartney number, written by John not long after they first met back in 1957, in their Quarrymen days when they would bunk off school and go to Paul’s house. They were trying to do a skiffle railway song, like the ones that were very popular at the time, such as ‘Rock Island Line’ and ‘Cumberland Gap’. They had recorded it in 1963, but George Martin–who in those days was still in charge of such decisions–thought it wasn’t good enough. Which it wasn’t. Lines like ‘Come on baby, don’t be cold as ice’ were not exactly poetic. Now, looking to fill up the Let It Be album, they decided they could get away with it. But even Paul admitted ‘we hated the words’.

The Long And Winding Road

The road itself has been named by Beatles analysts as the B842, a long and winding road from Paul’s cottage in Scotland with sixteen miles of twists and turns before it reaches anywhere–though Paul himself has never confirmed this was the road he had in mind. In his authorized biography, Many Years from Now, he says simply that he wrote it as a sad song, during some stormy recording sessions.

The lyrics are in fact very good, verging only marginally on the maudlin (‘pools of tears’); rhyming ‘cried’ with ‘tried’ is a bit feeble, but as a love song, about the long and winding road that leads to your front door, i.e. to love, it is moving and poignant.

Its worth has rather been obscured by the fact that it was this song that led to so many rows and scenes. In the Beatles history books, the experts tend to concentrate on the dramas of the recording sessions, rather than on the content.

The song had been recorded quickly, and not very well. John, who had done a poor job himself, therefore decided to call in Phil Spector to knock it into shape–without telling Paul, who was busy with his own solo album. Paul was naturally furious.

Spector turned it into a lush, mushy, orchestral smoochy number, like a corny Hollywood film score, with an over-the-top female choir in the background.

John’s defence was that if Paul had been allowed to work on it again, they would never have got Let It Be finished.

For You Blue

A George number, but unusually for him it’s a happy-go-lucky, catchy blues song, with no Indian influences or mystical, magical, mysterious lyrics. He also manages a very convincing falsetto, the sort of stuff usually left to Paul. John can be heard chattering in the background, but it doesn’t distract, nor mock the song. It’s a love song, presumably for Pattie; he loves her because she’s sweet and lovely. What could be nicer?

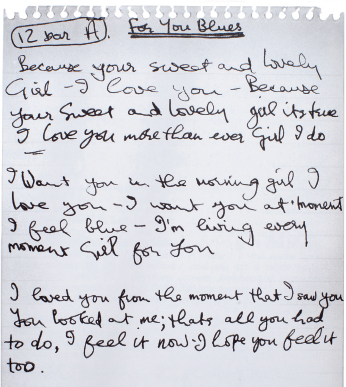

‘For You Blue’, from Let It Be, in George’s hand, with the title given a plural.

Because you’re sweet and lovely girl I love you,

Because you’re sweet and lovely girl it’s true,

I love you more than ever girl I do.

I want you in the morning girl I love you,

I want you at the moment I feel blue,

I’m living every moment girl for you.

I loved you from the moment I saw you,

You looked at me; that’s all you had to do,

I feel it now I hope you feel it too.

The Let It Be album finishes with ‘Get Back’, which had already been released as a single.

When the delayed album finally came out in May 1970, there was alas no chance of them getting back.