INTRODUCTION

The Beatles, so young, so keen, in their suite at the George V Hotel in Paris in late January/early February 1964. While there, they heard the news that ‘I Want To Hold Your Hand’ had got to number 1 in the USA. It was also in the suite that Paul created ‘Can’t Buy Me Love’. Left to right: Ringo, John, Paul, George. (Photograph@Harry Benson 1964)

One of the strange things about the Beatles phenomenon is that the further we get from them, the bigger they become. Their influence and our interest in them seems to grow all the time. When their old stuff is repackaged it often becomes even more successful than it was when first released. The scruffiest scrap of paper signed by them is worth a small fortune. All round the world there are universities studying their oeuvre–something I would have dismissed as ridiculous, back in the sixties.

Apple, the Beatles organization formed in 1968, never employed more than fifty people during its early years. I reckon that across the world today there are at least five thousand people making their living out of the Beatles: writers, researchers, dealers, academics, conference organizers, tourism and museum people, souvenir manufacturers, plus members of the several hundred or so tribute bands who dress up as Beatles and play their music all around the world, all year round. It is the music that turns them on–though it is of course excellent fun to go and worship at the tourist sites, attend a Beatles fair and buy rubbishy souvenir tat or have your photie taken on the crossing at Abbey Road.

If it is the music that matters, where did it all come from? How did they create their songs when they had no musical training and could not read or write music? What were their influences and inspirations? Even more mysterious, having got started, how come they suddenly metamorphosed, discarding childish, hackneyed, borrowed forms to blossom into the most admired, most studied, most gifted songwriters of our age–or perhaps of any age? All artists develop, but in the case of the Beatles the transformation was dramatic. Who would have thought that the minds responsible for ‘Love Me Do’ and ‘Please Please Me’ would go on to produce ‘Eleanor Rigby’ and ‘Across The Universe’?

Their music–the notes and chords, tunes and rhythms–has been well studied, well analysed, well applauded, almost from the moment they received any national attention. Exceedingly clever musicologists have taken apart the quavers and crotchets, dissected the harmonies, revealed the musical tricks and instruments used, numbered and marked all parts of the musical body. We now know exactly which notes were being played and by whom and for how long in that crashing, earth-shaking crescendo at the end of ‘A Day In The Life’. But what of the words?

The lyrics have, in comparison, been neglected. (Do note, by the way, it is the lyrics that mainly concern us here, not the melodies.) Can lyrics be pinned down and pulled apart? And even if they can, will it make them any better, any more interesting? Should we presume to analyse when most artists admit they themselves don’t always know where those words came from; or should we hold back, just let them be? After all, these are only pop lyrics not Shakespearean sonnets, so why do we need explanations or primers?

Because the creative process is always fascinating. Explanations are not necessary to our enjoyment of the piece, but information that helps to illuminate the process only adds to that enjoyment. So I decided to examine the original versions of their songs, discover how and when those words were first written down, how lines were changed or discarded along the way to the recording studio.

This was to become my self-imposed, self-created mission: to track down as many of the original manuscripts of the Beatles’ songs as possible. To look at their lyrics, both in first drafts and finished versions, and try to explain the meaning, the references, the names and places, phrases and expressions. To unveil them, as much as I could.

Can their lyrics be described as poetry? In one sense, no. They are part of songs–an art form where words and music fuse together and are complimentary. The lyrics were not intended to be considered as separate entities, so it is perhaps unfair to judge them on their own.

Unlike some songwriters, the Beatles never began a song with a complete set of verses, all written down. Mostly, they started out with scraps of words or phrases, or only the title. This was John’s normal practice. In Paul’s case, whole tunes did sometimes come to him, but the words came later.

Words mattered to both of them, though not so much in their early years and in their early songs, when they were following the formula of the time. It was the tune that mattered most. You don’t dance to words. The hook, the arresting phrase, was often enough. John was writing real poetry from an early age, in his own fashion, but these were inscribed on different pages, a different part of his brain; he never thought he could get away with writing what he really wanted to in something aimed at the mass market–or the meat market, as he often described it.

But John and Paul did have a literary bent, read widely, appreciated good writing and knew exactly what they didn’t like. They also, along with George, passed the eleven-plus exam and went to very good grammar schools and had a grounding in Eng literature, even if at the time they rubbished a lot of it, and the teachers.

The other day, in a moment of boredom, I studied the faces on the famous Sgt. Pepper cover–all people they admired or had been influenced by–and was surprised to find there were nine writers: Lewis Carroll, Edgar Allan Poe, Dylan Thomas, Aldous Huxley, Terry Southern, William Burroughs, H.G. Wells, George Bernard Shaw, Stephen Crane. The musical total came to only three: Bob Dylan, Stockhausen and Bobby Breen, a Canadian singer, born 1927, whom I must admit I had never heard of.

When John was gowing up, and was asked what he would like to do if he ever properly grew up, he would often answer: journalist. This was not the truth. He really wanted to be a poet, but thought it would sound unreal and pretentious to say so. In a 1975 interview with Rolling Stone magazine, asked what he thought he’d be doing in his sixties, John pictured himself writing children’s books. He wanted to write the sort of books that had given him such pleasure and inspiration as a boy–The Wind in the Willows, Alice in Wonderland, Treasure Island.

The fact that someone has literary interests does not mean they have literary talent. I personally think John and Paul did. And it was the main reason I wanted to meet them and why in 1966 I first went to interview Paul. ‘Eleanor Rigby’ had just been released and I was amazed not just by the tune but by the words. In The Sunday Times, I described the lyrics as the best of any contemporary pop song. As if I was qualified to pronounce on anything to do with English Lit.

I still can’t claim qualifications to examine literary text, no more than I have the knowledge and expertise to examine the music–though I can read music, having gone to violin lessons for five years as a child, which is five years longer than John or Paul ever managed. But I felt and still feel sufficiently emboldened to write about what I personally like and think about their songs, what I enjoy. This is partly because I am of their generation and background, growing up in the same sort of houses, attending the same sort of Northern grammar school, and also being around them for a short spell (as their biographer 1966–68). I therefore like to think–though it may possibly be my own fantasy–that I have some idea about what might have been in their minds, where the words might have come from.

The danger in writing about their songs, be it the words or the music, is to over-analyse and over-intellectualize. I find so many of the Beatles musicology books unreadable–not just because of the jargon, but because they are writing for specialists, often to impress and score points. The same has happened, to a much lesser extent, with the words. And it’s been mainly the more fanatical fans who have got carried away, finding hidden meanings and messages, drug references where none was intended. Quite often, as they progressed, John did throw in meaningless phrases, just to baffle and confuse listeners, and to amuse himself.

One of the attractions of popular music is that you don’t really have to know or understand or even like the words. They insinuate themselves into your skull and never leave. I remember as a child learning the words of a really rubbish wartime song called ‘Mairzy Doats’–just as John and Paul did, for I recall discussing it with them. It was only years later I discovered the words were ‘mares eat oats and does eat oats and little lambs eat ivy’. All nonsense, but no more so than many nursery rhymes that we all have lodged in our heads.

John thought most analysis of music was pretty much nonsense. In his letters, he rarely wrote about his music-making. There were no descriptions of the agonies of composition, the struggles he was going through to create–which is a common preoccupation in the correspondence of poets and the more literary of novelists. Only after the event did he occasionally give clues as to how and when a song got written, and even then only if asked.

No one really, truly knows where words come from. ‘Songs are like rabbits: they like to come out of their holes when you’re not looking,’ according to Canadian singer-songwriter Neil Young. T.S. Eliot said that the words in a poem were there to ‘divert’ the mind. This is even more the case with lyrics, which often get chosen for their sound, to fit the musical mood, rather than to convey precise meanings, which tends to make analysing them rather a challenge.

However, this has not put off the academics. One of the earliest and most comprehensive studies of Beatles lyrics was published by Colin Campbell and Allan Murphy: Things We Said Today: The Complete Lyrics and a Concordance to the Beatles’ Songs 1962–1970. Campbell, later to become Professor of Sociology at York University, was teaching at a university in Vancouver at the time. They transcribed all the lyrics on to a computer–which in the seventies must have been a massive task in itself, as computers were about the size of Wembley Stadium–and then analysed them. The results allowed them to reveal to the world the most frequently mentioned colour in the Beatles’ lyrics: blue, with 35 mentions, followed by yellow, 32. This does not take into account the fact that half of the ‘blues’ refer to the mood rather than the colour, and most of the yellows feature in a single song. As with all statistics, the answers often lead to further questions.

Campbell and Murphy’s book did, however, feature an excellent introduction in which they traced the development of the lyrics, highlighted the use of homophones (such as, should it be ‘I say high, you say low’ or ‘I say “Hi”, you say “ ’Lo” ’?) Listening to the songs, it’s hard to know which meaning they intend–and in many cases it might not occur to the listener that there could be an alternative meaning–but I am sure the Beatles did it consciously, loving double meanings.

The academic musicologists, almost from the beginning, were so intent on comparing Beatles tunes with Schubert and Schuman that they gave little thought to the words and whether they might be up there with any of our great poets. Campbell and Murphy in their study started by making a case for Robert Burns as a rough literary equivalent–a songwriter with a lyrical gift, who wrote love ballads, often in the vernacular. They then went on to declare that the most fitting comparison would be Wordsworth–which I think is pushing it, as the traditions of his times were so different.

It’s true that Wordsworth wrote about his own life in The Prelude, and as a Romantic he advocated letting Nature be our teacher–just as Lennon, particularly in his later songs, asked us to look around and let Love be our teacher; it’s also true that Wordsworth came up with some fairly banal lines, such as his description of a pond: ‘I measured it from side to side/’tis three feet long and two foot wide.’ While working on a Wordsworth biography I raised this with the Dove Cottage experts; their response was defensive, asserting that since Wordsworth was a genius all his compositions, even that one, must be subjected to serious study and consideration and not mocked.

I suppose the same defence can be used when studying the Beatles’ lyrics. The lyrics of ‘Love Me Do’ might seem banal, but should not be dismissed. It is part of their oeuvre–and more importantly, it was how they began.

But of course we must avoid too much analysing. It will only annoy John, sitting up there.

‘Listen, writing about music is like talking about fucking,’ as he told Playboy magazine in 1980. ‘Who wants to talk about it?’

The reasons why a book using the original manuscripts of their lyrics has not appeared before is primarily because of the dreaded laws of copyright. When I edited The John Lennon Letters it was relatively simple: all I had to secure was the permission and agreement of Yoko Ono, owner of the Lennon copyright, which she gladly gave. Then find the letters.

When I first embarked on this project, I thought the copyright of any original manuscripts must still belong to Paul McCartney and the Lennon estate, and some to the Harrison estate. I contacted Paul and Yoko and each seemed interested in the project, and appeared willing to help.

Then, after legal soundings, and a lot of casting about, I was informed by Sony/ATV that the publishing copyright of almost every Beatles’ song is owned by them and it covers all versions of their songs, even ones they do not know exist.

Before mechanical recording of songs came in, a music publisher was someone who physically published the music and words of a song in the form of sheet music. That’s how people in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries would learn the latest songs, playing them on an instrument or singing them. From around 1900 onwards, the publisher–who of course was spending money and taking all the risks–owned the copyright and took 50 per cent of all proceeds. When gramophone records came in, the system continued and until 1952 it was sales of sheet music which determined the UK’s weekly hit parade. After that, the sales and influence of sheet music declined, but the power of the music publisher remained.

The Beatles’ music publisher from almost the beginning of their career was Dick James, under the banner of Northern Songs. He owned 50 per cent, the traditional split, while the other half was divided between John and Paul and Brian Epstein, their manager, with minor shares belonging to George Harrison and Ringo Starr.

In 1969, Dick James sold his share to Lew Grade of ATV–and the Beatles were persuaded to do the same. At the time, they were paying income tax at around 90 per cent in the pound and this was a way of making a quick tax-free gain.

In 1985, the rights came up for sale again. Paul and Yoko had not been on the best of terms, but they were interested and tried to get the price down. While they hesitated, in stepped Michael Jackson–and bought the lot for a reported sum of £24 million. In 2005, Jackson had money problems and did a deal with Sony, receiving around £60 million for half the ownership. Since his death, Sony/ATV has been controlling all the rights.

Throughout this period, ever since Northern Songs sold out, every time Paul has performed ‘Yesterday’ in public he has been required to pay a copyright fee–even though he is singing his own song, one he composed. Though as a performer, like all performers, he still gets a performance fee, administered by the Performing Rights Society.

The next major hurdle was locating the manuscripts. I happen to have acquired nine of them, back in the sixties, which is how my interest in them first began. While I was in the studio at Abbey Road, late at night, there would often be scraps of paper lying around. Many of these were just left at the end of the night for the cleaners to burn. Now and again, if I had been following a particular song from the beginning and knew I was going to write about it in the book, I would ask if I could have them. And they would say yes, of course, otherwise they will only be binned.

The Beatles, at that stage, had no interest in where they had come from or what they had done so far, only in the next thing. They were very young, still in their mid-twenties, an age when you rarely think of keeping stuff. Anyway, the point of being in the recording studio was to record; once the new song was captured on tape, why keep the scribbled words? It was just scrap paper to them.

Whenever I visited their homes, I would ask if they had lyrics of any earlier songs that I wanted to write about, and they would rummage around and give me the odd scrap. All of these I kept, long after the book was published, just as I kept the memorabilia and ephemera–from football programmes to guide books of the forts on Hadrian’s Wall–picked up while doing my other forty or so non-fiction books. None of the latter has turned out to be at all valuable. But the Beatles memorabilia? Towards the end of 1981, I woke up one day to discover that Sotheby’s had had their first auction of Beatles bits–and that my nine lyrics were worth more than my house.

The first major auction of Beatles material was held at Sotheby’s in London in December 1981.

I rang the British Museum, offering the collection to them on permanent loan, thinking they might say, Nah, we don’t do pop music, but they were pleased to accept it. When the new British Library building opened in 1997 in Euston Road, my collection was transferred to their Manuscript Room, where it remains to this day, next to Magna Carta and the works of Shakespeare, Beethoven, Wordsworth and a host of other creative greats. In my will, they will go permanently to the British Library–as some of them already have done. If I were to sell them on the open market, I know they would end up in the USA or Japan. I want them kept together, as a collection, here in the UK, available to be seen and studied.

It was not until I began this project that I learned mine is the largest known collection of Beatles lyrics in a public archive. (We don’t know precisely what Paul and Yoko themselves own–but both have private archives.) I have discovered, though, another equally important and almost as extensive collection in the USA, at Northwestern University in Illinois, gathered together by John Cage (1912–92), the American composer whose most famous piece was called ‘4'33"’–because it lasted exactly 4 minutes and 33 seconds. The piece, which had to be performed in silence, still receives regular performances around the world. It was the sort of avant-garde music and art that by 1966 Paul and John, now they had become London arty types, were interested in.

Back in 1966 Cage was collecting original musical scores and lyrics to benefit the Foundation of Contemporary Performance Arts. Yoko Ono, a friend of Cage’s, managed to persuade John (whom she had recently met although they were not as yet together) to hand over six lyrics. The Beatles were by then in the middle of Revolver, and the manuscripts were from that album. Then Yoko turned up at Paul’s one day and got from him the coloured manuscript of ‘The Word’ from Rubber Soul (here).

Cage’s seven Beatles lyrics were acquired by Northwestern University in 1973–74. ‘Today they are some of the most valuable items we hold,’ says D.J. Hoek, the present head of the Music Library. ‘They are the initial expression of a musical idea on paper.’

Aside from Northwestern, I have been unable to find any other proper collections of Beatles lyrics, at least not in known or public hands, but there could be some billionaire with a stash of them in his den. I doubt it, somehow; these days, they very rarely come up and prices start at around $250,000–and on two occasions they have reached the $1,000,000 mark. But there must be individual collectors who bought a lyric relatively cheaply when they first started appearing for sale in the 1980s. And also people like me, who were given them by John, Paul and George many years earlier. Those people who went on to sell them, often did so privately, through dealers rather than in the public auction rooms, so no records are available. I do know of one person, a friend of Paul’s, who was trying to sell seven lyrics back in the 1970s, offering them to various institutions (including Northwestern); in the end he sold them at a London auction house. They are now dispersed around the world, owned by various individuals.

The Quarrymen in November 1957. Paul and John are at the microphones, in white jackets, indicating that they are the joint leaders.

In trying to track down original manuscripts of the lyrics, I did the obvious things: approached all the main auctions houses, such as Sotheby’s, Christie’s and Bonhams, and the main memorabilia dealers, such as Tracks in the UK. I also contacted collectors who might have any, even copies, and also Beatles experts, researchers and academics who have made a life study of Beatles music. Fortunately, many of those I contacted had kept good scans, which they were kind enough to let me have. (They don’t of course own the publishing copyright; that belongs to our dear friends at Sony.)

I also made contact with several private collectors who own original lyrics, but in almost every case they requested no publicity. They don’t want to run the risk of being burgled, or for people to know what they own.

Some of the manuscripts are mere scraps, some hard to read, and some almost identical to the recorded lyric, but these remain of interest, to me anyway, if only to see their handwriting. The most difficult to locate have been the lyrics from the early years, perhaps because they were rarely written down in those days. ‘Love Me Do’, for example, has very few words, so there was little need to write them down. Those early recordings were done quickly, with the band in and out of the studio in as short a time as possible, with few people around. No one thought of preserving scruffy scraps of paper.

When it came to the later albums, circa 1965 and onwards, I managed to track down more and more, till eventually–as in the case of Sgt. Pepper–I had succeeded in tracing some sort of manuscript version of every number on the entire album. So in the end I did reach my target of one hundred Beatles songs.

How many songs are there in total? It depends how you define a Beatles song. My definition is a song composed and recorded by the Beatles, during the period they were the Beatles, i.e. until the band finally split in 1970. So that precludes recordings of songs composed by other people–something they often did in their early days; songs they composed but gave to others to perform and never recorded themselves; songs created after the Beatles ceased to exist and they became solo artists; songs without lyrics, i.e. instrumentals such as ‘Flying’ on the Magical Mystery Tour album; variations of the same song, such as the reprise of the Sgt. Pepper title song or ‘Revolution’. By that reckoning, my total of Beatles songs comes to 182.

I have almost always tried to arrange them chronologically in the order in which we, the fans, heard them, which was not necessarily the order in which they were written or recorded. Roughly speaking, there was little divergence until the very end when Let It Be, the film and the album, came out chronologically last, for various complicated reasons, while the real last album, the final one they worked on and gave to us, was Abbey Road.

Where I have secured a manuscript, by which I mean an image of an original handwritten version, I have also included the final recorded and published version, so you can compare the two. With the lyrics–i.e. the final recorded version–also note that when there are endless repetitions of the chorus, or verses, or the same lines, I did not always include the repetitions, just to save space.

In considering them chronologically, I have also tried to tell the story of the band’s music-making and its development. Their music comes out of their lives, just as their lives and feelings and emotions got reflected back into their music. So in some ways it has become the story of their lives as told through their music.

Paul and John–and George: a Brief Musical Biography

Paul and John met through music–and for no other reason. They didn’t attend the same school or even live in the same area, in fact they had never even met prior to Saturday, 6 July 1957, when John’s little schoolboy group, the Quarrymen, played at a church fête in Woolton, Liverpool, and Paul was brought along by a mutual acquaintance, Ivan Vaughan, a friend of John’s who attended the same school as Paul.

Paul, just turned fifteen, brought his guitar along, and after watching the Quarrymen perform he was introduced to John, the group’s leader, and proceeded to demonstrate his expertise on the guitar, playing a number called ‘Twenty Flight Rock’. John was impressed, but of course tried not to show it, being tough, being the boss. He realized that Paul knew more chords and was probably a better guitarist than him, so for a week he pondered whether it would be a good idea to introduce a rival into the group. On reflection, he decided yes and invited Paul to join. A year later, George Harrison, who was at the same school as Paul, a year younger but already as good a guitarist as either of them, was introduced by Paul to John and he too became one of the Quarrymen.

John with the Quarrymen in 1957.

Looking back, it was remarkable that three people we now consider to have been such talented performers and composers should have grown up together at the same time, in the same place, and then joined together, and stayed together, for the next thirteen years. There was every chance they might never have met–or met very briefly and then gone their separate ways. There were thousands of youths of their age in the Liverpool area, let alone the rest of Britain, all loving the same sort of music, trying to play it, joining little groups, breaking up and moving on to other ventures. One of the original Quarrymen, the drummer Colin Hanton, went on to become an upholsterer. Another, Rod Davis, who became head boy of Quarry Bank School and later went on to Cambridge, was at the time, back in 1957, just as proficient a musician as John and the others.

So what was it in John, Paul and George that made them persevere when for a long time the world showed no interest in what they were doing–which was mainly begging for humble engagements at parties and village halls.

John always said that, but for the Beatles coming along, he would have ended up like his dad, doing nothing very much, or failing that, a tramp. Paul, who was always more calculating, more clued up, did have some paper qualifications, having sat his A levels, and could well have gone on to training college and become a teacher, which would have pleased his father. But he, along with John and George, eventually became obsessed with making music, ignoring the advice of most adults and family members who warned that they would never make a living at it.

In 1964, Paul gave an interview to an American Beatles magazine, just before their USA tour, in which he said that his ambition had always been to get into some sort of group and stay in it for a few years–hopefully till the age of twenty-five. Then he would give it up and go to art college, the one John had attended, ‘And hang out there for a few years.’

I remembered his father, Jim, telling me that as a boy Paul had been just as interested in drawing and painting as he had been in music. Similarly, John, when he was growing up, had spent most of his spare time writing stories and poems, drawing cartoons and pictures. So that subsequent total passion for music, which came about in their teenage years, had not been an all-consuming factor when they were growing up.

As youngsters, both John and Paul had been offered music lessons by devoted and caring parents, but both later admitted that they simply couldn’t be bothered, they were too lazy, moreover they hated people telling them how to do things. So where did the talent for music come from?

In the case of John–born 9 October 1940, and brought up by his Aunt Mimi after his parents split–there was a vague musical background in the family. His father, Freddie, who went off to sea, had a good singing voice (so he told me, and of course I believed him) and would entertain his friends at get-togethers with a song or two, but he never did it for a living. His own father, also called John Lennon, had for a time toured the USA as part of a group of Kentucky minstrels. It proved to be nothing more than an interlude in his early life; at the end of the tour he returned to Liverpool, where he spent the remainder of his working days as a clerk.

John’s mother, Julia, played the banjo well enough to teach John some basic chords and encourage him to continue. She also played the accordion, according to her daughter Julia Baird (John’s half-sister) and had a good singing voice, but could not read music. ‘She was forever singing,’ remembers Julia. John was fifteen when his mother died in a car accident, just as she was coming back into his life again.

John’s Aunt Mimi was so against him playing guitar that she made him practise outside in the porch. She appears to have had no interest in music, at least popular music. ‘I think the maternal side of our family,’ says David Birch, John’s cousin (son of his Aunt Harriet), ‘can fairly be described as tone deaf–apart from his mother Julia.’

Pauline Lennon, now Pauline Stone, the widow of Freddie, John’s father, says that Freddie couldn’t play an instrument or read music. ‘But he had excellent pitch and rhythm and loved to sing. In fact he was always singing. It was impossible ever to feel down with him around. Mainly it was popular ballads, like “Smile” or “Blue Moon” but also a bit of opera–I also remember him singing “Nessun Dorma”. He had a tenor voice, but I’d describe him as a “crooner”.’

John also learned to play the mouth organ as a young boy, after a fashion. His Uncle George (husband of Mimi) had given him a cheap one and he took it with him on a bus trip to Edinburgh to stay with his aunt, playing it for the entire journey. The bus driver told him to come back to the bus station next day–and presented him with a much better one.

Paul, born 18 June 1942, had a much stronger musical heritage. His father, Jim, although never a full-time professional musician (he spent his working life as a cotton salesman), did have his own little jazz band before the war: Jim Mac’s Band. Paul remembers as a boy loving all the family gatherings where his uncles and aunts would sing songs and play instruments. In this the McCartneys were fairly typical; most extended working-class families could boast at least one amateur musician able to play the piano or the fiddle–self-taught–always on call for a good old-fashioned family knees-up.

Jim played the piano and the trumpet–until his teeth went–and they had instruments in the house, but because he played by ear he felt unable to teach Paul how to play, not knowing the rules and the language. Paul did have a couple of lessons, then gave up. But his aptitude was clearly always there, encouraged by Jim, who told him that if he learned the piano he would always be invited to parties.

As for George, born 25 February 1943, neither of his parents appear to have been very musical. George’s father, a bus driver, had owned a guitar at one time, during the war, but he does not appear to have played it while George was growing up. George’s mother Louise enjoyed a sing-song and, unlike John’s Aunt Mimi, she actively encouraged George when he joined the Quarrymen, going along to watch them play.

Both Paul and George grew up in homes where the radio was blaring out all the time, usually popular music, whereas John’s Aunt Mimi preferred silence. It was one of the reasons John was rather impressed by their musical knowledge in the early days.

In 1963, the Record Mirror submitted seventy-eight questions to each of the Beatles. (The results were never published, presumably because only Paul and Ringo filled them in properly, while the other two mucked about and didn’t answer them all.) One of the questions asked them to name their biggest musical influence; Paul’s answer–in John’s handwriting–is ‘John’. Why? ‘Because he’s great’. Paul has then scored this out and written ‘My Dad’.

Asked what his Dad thought of his music, Paul responded: ‘My Dad likes it, but he thinks we are away a bit too much.’ Did he encourage your music? ‘Not half. He suffered my practising for years.’ Asked what else his parents would have liked him to be, ‘Clever,’ replies Paul.

Paul’s mother Mary died in 1956 from breast cancer. Paul was fourteen at the time and his younger brother Michael recalls it was around then that Paul’s obsession with the guitar began, throwing himself into learning to play it. Was it a compensation mechanism? Would it have happened otherwise? The first song Paul remembers writing was ‘I Lost My Little Girl’ which he thinks he wrote when he was about fourteen. He played it to John, not long after they first met.

Mary McCartney, like George’s mother, was Roman Catholic, but neither Paul nor George were sent to Catholic schools. In fact, they attended Church of England Sunday schools, as did John. Paul was a keen choirboy, and he had a good clear singing voice, as did his younger brother Michael. Though none of the Beatles’ parents was overtly religious or even regular church-goers, the boys followed working-class conventions of forties and fifties Britain whereby children were sent to church or Sunday school on a Sunday, giving their parents a break and perhaps the opportunity for a bit of a Sunday-morning cuddle.

The Beatles in 1960, then called the Silver Beetles, auditioning before Larry Parnes, which led to their first tour, two weeks as a backing group to the north of Scotland. Far left is Stu Sutcliffe, who had just joined the group. The drummer, looking pretty bored, was a stand-in. Left to right: John, Paul and George.

Did their Catholic mothers–in the case of Paul and George–and regular Church of England attendance have any influence on their musical tastes and knowledge? A case has been made out for the effect of religion on their music. But I think it is fairly minimal.

And what of their Irish ancestry? Paul and John both had Irish roots, as did George, through his mother. The Irish, so we are always told, are very musical. But then so, traditionally, are Merseysiders. In fact we all are, if we go back far enough. The folk tradition of stories and songs passed on orally from one generation to the next exists in every culture.

There is another minor element in their inherited make-up, which did come out in their music, and that is humour. Merseyside humour is built on mockery, irony, sarcasm, satire, not taking yourself too seriously, or others. According to the late Ian MacDonald, author of an excellent book on the Beatles records, mainly about their music, ‘Liverpool is a designated area of outstanding natural sarcasm’. As their lyrics progressed, there is a lot of humour, as we shall see, jokes, puns, word-play, pastiche. Even when being terribly serious and preachy–which they could be at times, delivering morals and messages–they usually ended with a laugh, mocking themselves.

Even if we agree that John and Paul inherited some musical talent from one or other of their parents, and that their family life and upbringing in Liverpool did have an influence on their music, we all know that that is not quite enough to account for their genius, otherwise loads of us would have written ‘Yesterday’. One of the common clichés about genius is that it is 10 per cent inspiration to 90 per cent perspiration.

The Beatles certainly worked extremely hard. When they first appeared, in London and later in New York, they were assumed to be overnight sensations who had come from nowhere. In fact they spent the six years leading up to 1963 unknown and mostly unpaid, struggling to be the Beatles, which equals the six years they spent as the world-famous Fab Four until the band broke up in 1969.

Paul might later have exaggerated how many songs they wrote in those early years, but they did write loads. And the songwriting didn’t fall off when they became famous. Far from sitting back on their laurels, idly counting their money and gold discs, or lazily repeating a tried-and-trusted formula, they continued onwards and upwards–and occasionally sideways and backwards. The important thing was to evolve, move on, try something new. Their output from 1963–1965 was prodigious. While travelling hundreds of thousands of miles, performing hundreds of live concerts, recording films, TV shows and interviews, they still managed to bring out album after album of new and wonderful songs.

Their musical talent may have been something they were born with, but arguably the most important elements in the creation of the Beatles’ music were hard work and dedication. Without those ingredients, their legacy would have been puny.

The spark that first brought the band to life, that drew out what was lurking inside, was skiffle. This was home-made, do-it-yourself music, the kind anyone could have a go at, even if they couldn’t play an instrument, or didn’t even have an instrument. Lonnie Donegan’s ‘Rock Island Line’, which was a hit in 1956, was a huge influence, encouraging the untrained and the unmusical to have a go, even if all they did was scrape a washboard with a thimble or twang a tea-chest bass. That same year, Elvis Presley’s ‘Heartbreak Hotel’ went to the top of the charts in fourteen countries. Then there was Bill Haley with his ‘Rock Around The Clock’, the theme tune for the film Blackboard Jungle, which had British teenage audiences ripping up cinema seats. Suddenly, the young John, Paul and George had new musical idols whose records they rushed out to buy or borrow, to listen to and work out how it was done.

Their first instinct was to copy. How could it not be? They wanted to reproduce the noises they liked and the words being sung. As they progressed, and they got a bit better on their guitars, their tastes progressed. They became desperate for the latest American rock and roll records.

What was unusual about the coming together of Paul and John was that they moved on almost at once from copying to creating their own versions. But they still followed the format of the day when it came to what constituted a pop song. It had to be just under four minutes long and preferably about boy–girl love. The words didn’t really matter as long as it had a hook, a catchy title or phrase, and an exciting beat or infectious melody. Happy, hopeful, romantic love was the preferred subject matter, though you could also write about the opposite side of the coin–unhappy, miserable love, tears and pain–but not too often or your audience would get fed up and go elsewhere. Regardless of what the song was about, it was vital that you could dance to the tune. Even the unhappy, slow ones. That was about it, really.

John and Paul began writing songs when Paul was still only fifteen, not long after they first met. He would bunk off school and go home to their empty council house at 20 Forthlin Road while his father was at work. John would join him. It became easier for John to spend time there after he started art college in 1958. Nobody, least of all Mimi, knew where he was most of the time.

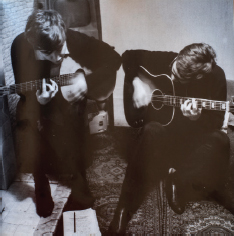

They would play their guitars, head to head, watching each other, learning new chords, trying out different fingering, copying and criticizing each other. As they made up songs they wrote the titles down in a school exercise book, sometimes with an attempt at trying to list the chord sequence so they would remember it, using their own made-up notation. Each song was marked as ‘another Lennon and McCartney original’. Within a year or so, Paul was boasting that they had already written between seventy and one hundred songs–the number varied, and was usually greatly exaggerated.

There is an early photograph, taken by Paul’s brother Michael, that shows them in the front parlour at Forthlin Road, which was where the piano was, though that can’t be seen in the photograph. They are sitting side by side in front of the fireplace, both in black, like mirror reflections–Paul, being left-handed, holds the guitar under his left arm, while John has his under his right. They seem joined together, one body with two heads. Both are leaning forward, looking down at the notes for a song written in an exercise book lying on the floor in front of them. According to Michael, the song they were playing that day was ‘I Saw Her Standing There’. He says that he once blew the photo up and could see that the first words were in fact ‘He’ and then ‘She’, but these were both crossed out before they settled on ‘I’ saw her standing there.

At one time, John and Paul decided to write a play. ‘It was a serious play,’ so John recalled in a New Musical Express interview in 1963. ‘It was about Jesus coming back to earth today and living in the slums. We called the character Pilchard. It fell through in the end.’

They also wrote short stories together, which indicates that their creative urges were not solely directed towards pop songs. John of course was writing nonsense verse, joke and cartoons from an early age–many of which later emerged in his two books of poems.

Paul and John, left- and right-handers, like mirror reflections, caught composing together by Paul’s brother Michael in 1962. On the floor is an exercise book with their earliest songs.

Their joint song writing continued and it led to them making their first primitive record. One day, some time in the summer of 1958, they walked into the little DIY recording studio of an elderly gentleman called Percy Phillips in the Kensington area of Liverpool. On one side they recorded ‘That’ll Be The Day’, Buddy Holly’s 1957 classic, and on the other their own composition, ‘In Spite Of All The Danger’.

It cost them seventeen shillings and sixpence, which worked out at three shillings and sixpence each for the five Quarrymen who took part that day. It was the most they could afford, and they ended up with only one copy of their record. They took turns to have it, a week or so at a time, to show it off to friends and family. The last one to have it was John Duff Lowe, a member of the Quarrymen at the time, a school pal of Paul’s, who played the piano. He kept it for the next two decades, by which time it had been as good as forgotten. When I was interviewing John, Paul and George in 1966–68 for the biography, not one of them mentioned it.

John Duff Lowe, now a retired businessman living in the West Country, remembers it well:

I can clearly recall rehearsing ‘In Spite of All the Danger’ at Paul’s house during our Sunday afternoon rehearsals, and Paul showing me how he wanted me to play bluesy accents–playing a black key with an adjacent white one–which you can clearly hear on the recording.

It ran for four minutes, which we were not supposed to do. This had Percy Phillips pulling his finger across his throat, indicating we had to stop at three minutes fifty seconds. When the original is played, the needle rises a millisecond after George’s last chord, a single strum. He probably did it in the heat of the moment, knowing we had run out of time.

The first recorded song, ‘In Spite Of All The Danger’, by the Beatles, then the Quarrymen, in 1958. Only one copy was ever made.

When the record reappeared in the 1980s it was obvious that, as a unique part of early Beatles history, it was a worth a fortune. It was all set to go to auction but Paul stepped in and bought it privately. Today it is often described as the single most valuable record in history and would be worth a small fortune if it ever came on the market again. In 1995 it was heard for the first time on the Beatles’ Anthology album.

The interesting thing about the record is the fact that they included a self-composed number. The home-made disc label credits the composers as ‘McCartney, Harrison’. In reality, it was all Paul, trying to do an Elvis-type ballad, but George got a credit for helping with the arrangement. John is the lead vocalist on both songs with Paul and George backing up on harmonies.

The lyrics are fairly unmemorable: ‘In spite of all the danger / In spite of all that may be / I’ll do anything for you / Anything you want me to / If you’ll be true to me.’

I have always been intrigued by the precise meaning. If it is just a boy–girl love song, as it appears, then why would there be any danger? It’s almost as if an illicit affair was going on, perhaps with a married woman, but how could that be, for a teenage boy in 1958, when sex had not yet been invented?*

Paul might well have been subconsciously thinking of his first sexual experience, which he later told me about, and which I used in my 1968 biography: ‘I got it first at fifteen. She was older and bigger than me. She was supposed to be babysitting while her mother was out.’ So that could have been the danger.

In August 1960 they made their first of five trips to play in Hamburg, a stage in their life seen as vital for their development as performers, helping them to create their own distinctive sound. It is interesting to wonder whether that would have come about if Paul’s mother had lived? As a trained nurse and midwife, she was keen on her sons’ education and on their economic and social improvement. She might well have insisted that he stayed on at grammar school to complete his studies. John’s Aunt Mimi had less influence in his life after he became an art student, while George, who had already left school and started a fairly pointless apprenticeship, was encouraged by his mother in all his musical activities. Mary McCartney, however, might well have put her foot down. And Paul, being a dutiful son, might well have given in. Then what would have happened? Would John and George have gone to Hamburg without Paul, splitting the Lennon–McCartney partnership before it had even begun?

In Hamburg they got their second experience of a recording studio, but only as the backing group for a singer called Tony Sheridan. I have a copy of the contract they signed with Bert Kaempfert Produktion dated 1 July 1961. Clause 7 states that John is ‘authorized as the Group’s representative to receive the payments’. John was the leader, as he had started the group. Whereas Paul’s full name, James Paul McCartney, is given, John Winston Lennon is listed as John W. Lennon. Pete Best was their drummer at the time, before the change to Ringo.

German contract for the Beatles, 1961, as a backing group, giving their home addresses.