INTRODUCTION

Each age, one may predict, will find its own symbols in Moby-Dick. Over that ocean the clouds will pass and change, and the ocean itself will mirror back those changes from its own depths.

Lewis Mumford, Herman Melville, 19291

On the morning that Captain Ahab is going to die, he stands aloft at the masthead for one last time. In a few hours the line attached to the harpoon that he’s going to hurl at the White Whale will snatch around his own neck and pull him overboard to drown. Suspended some ten stories above the waves, Ahab says to himself: “But let me have one more good round look aloft here at the sea; there’s time for that. An old, old sight, and yet somehow so young; aye, and not changed a wink since I first saw it, a boy, from the sand-hills of Nantucket! The same!—the same!—the same to Noah as to me.”2

Was Ahab’s ocean really the same as Noah’s? Was it the same as ours? Herman Melville (1819–1891) completed Moby-Dick; or, The Whale in 1851. He set the story about a decade earlier. His mid-nineteenth century was a period of tremendous upheaval and revelation about humanity’s place in the natural world, and his novel was by far the most profound American literary work about the ocean at the time. It would remain so for at least another century, and perhaps it still is. This natural history in front of you is the story of how Moby-Dick serves as a gauge to capture that American knowledge and perception of the ocean and its inhabitants—and how that view of the sea has changed up through today. Moby-Dick was the first novel, for example, to feature ocean animals to suggest such significant metaphorical and spiritual implications for our own behavior. Reading Moby-Dick in the twenty-first century, now well in the Anthropocene, we can read this novel as a proto-Darwinian, proto-environmentalist masterpiece of ocean nature writing that still has much to say, even when applied to our current global crises.3

Ishmael explains multiple times in Moby-Dick that two-thirds of the earth is covered by water. Geographers today estimate it at almost seventy-one percent. Melville understood or intuited, as remains true, that the sea drives our climate, our biodiversity, our economy, our international politics, and our imaginations. The ocean remains the most expansive, fascinating, complex, and sublime ecosystem on our planet. The ocean still supports—to us—some of the strangest and least known life-forms on Earth.4

When I first went to sea in 1993 out of Vancouver, British Columbia, I was twenty-two years old, a few months older than Melville when he first sailed on a whaleship from New Bedford in 1841. When I boarded my ship, a three-masted barquentine named Concordia, I too was bound for the South Pacific. A freshly minted teacher of English, I sailed out of Vancouver and spent eleven months with North American high school students, tracing an enormous figure-eight around the Pacific with the Hawaiian Islands at the center. We sailed to, among other places, Hilo, Majuro, Darwin, Papua New Guinea, Bali, Oahu, Fiji, Sydney, and Pitcairn Island, finishing in San Francisco. I read Moby-Dick for the first time sitting in a thatched chair in Moorea, French Polynesia. I read for four straight days, unaware that Melville himself had ambled around that same island, maybe even that exact beach.

One afternoon, a few weeks into teaching Moby-Dick and some nine months into that first voyage, I was rereading the novel as we sailed for Easter Island. I needed some time and space, so I climbed up the rigging to see the curvature of the horizon. I climbed aloft all the way to the royal yard, over one hundred feet above the surface. Leaning out over the starboard royal yardarm, the absolute highest and farthest place I could get from the deck, I saw far off the bow what I believed to be the forward, single puff of a sperm whale. I had been so nose deep in the novel—studying Christian symbolism, Fascist parallels, and connections to Milton’s Paradise Lost—that the sight of a living sperm whale bordered on miraculous. I didn’t shout down to the deck. The puff of mist seemed an offering to me alone. I watched the whale’s flukes as it dove.

What I realized in the days that followed was that for me Moby-Dick is first and foremost a novel about the living, breathing, awe-inspiring global ocean and its inhabitants. Most explorations of this great American novel breeze too quickly past the marine life at sea that Melville so treasured and illuminated.

This natural history aims to provide that background by moving roughly chronologically through the voyage of the Pequod, exploring topics in marine biology, oceanography, and the science of navigation as Ishmael takes them up in Moby-Dick.

Now more than twenty-five years from my first voyage, I, like so many other readers of Moby-Dick, perceive the world’s oceans to be vulnerable, fragile, and in need of our stewardship. We have overfished the water, overdeveloped coastal habitats, and rocketed the rate of the introduction of marine invasive species. We have polluted the sea with oil spills, chemical runoff, and pervasive plastics. The amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has increased by over seventy percent since Melville’s years at sea, and is still rising. Since the first records in 1895, this carbon dioxide has not only increased the average US air temperature by between 1.3˚F to 1.9˚F, it has also altered the entire chemistry and temperature of the ocean itself—a seemingly impossible conceit. We hurl harpoons at a faceless ocean, slowly killing ourselves as we drag down entire ecosystems of life along with us. Because of sea level rise and the ungraspable phantom of melting polar and glacial ice, Melville sailed over a Pacific Ocean in the 1840s that was likely at least eight inches lower than it is today.5

Yet as we watch the ice melt on television documentaries, as we try to mitigate the erosion of our coasts due to sea level rise and the effect climate change has had on island, coastal, and Arctic communities, as we prepare for the next hurricane, and as we passively, Ishmael-like, forgive ourselves for buying just one more plastic bottle of water or another bite of tuna sushi, we somehow simultaneously perceive the ocean as more than simply vulnerable and in need of our protection. Because we still, somehow simultaneously, perhaps even because of novels such as Moby-Dick, continue to revere our twenty-first-century ocean in a similar way as did Noah, Jonah, and Ahab. We still envision the sea, even with all our technological advancements and scientific knowledge, as relentless and indifferent and immortal and sublime and eager to lure us in with a trace of sympathy and kindness then kick our ass and not even look back.

For example: many years after I sailed aboard the Concordia, on the afternoon of February 17, 2010, about 300 nautical miles off the coast of Brazil, a powerful squall caught the ship. The helmsman adjusted course to run before it, but too slowly. The wind heeled the Concordia so far on her side, so quickly, that hatches, doorways, and vents—which in retrospect should’ve been closed—began to downflood with ocean as the ship was knocked down on its side. The yard on which I’d leaned so many years earlier on my first voyage now crashed and stabbed the surface of chaotic seas. Sails filled with sea water. From belowdecks students and crew scrambled up along bulkheads, now sideways, desperate to get out. Somehow every single student, teacher, and member of the professional crew made it into four inflatable life rafts. The bosun swam to recover the rescue beacon. The wind blew the rafts crammed with people to leeward. Sometime after they floated away in terror, their Concordia, my Concordia, sank to the bottom. The sixty-four castaways floated for thirty-six hours without any steerage or any knowledge whether anyone anywhere knew what had happened. Following their radio and GPS signals, and then flares, the Brazilian Navy and two merchant ships, the Crystal Pioneer and the Hokuetsu Delight, rescued all hands.6

Tragedy at sea in the twenty-first century is less of an aberration than you might think. The sea still takes our largest steel-hulled ships. Eighty-five large ships were lost around the world in 2015. That was the fewest in a decade. One of those lost that year was the nearly 800′ long US merchant vessel El Faro, which was overwhelmed in a hurricane and drowned. The ship lost power, lost steerage, and sank in waters that were about three miles deep. Mitchell Kuflik, aged twenty-six, was one of the thirty-three men who died. Mitchell grew up in my town of Mystic, Connecticut. His fiancé was my daughter’s first babysitter.7

In Moby-Dick, Herman Melville wrote of both the beauty and the cruelty of the ocean. He summed up the nineteenth-century view of the sea and foreshadowed Ahab and his crew’s death in a single spiked club of a sentence that he tucked into a brief chapter about, of all things, zooplankton. I think this sentence is the most profound summary in the English language about the human relationship with the ocean—pre-Darwin, pre-Carson, and before any introduction of the concept of the Anthropocene. Melville slipped this single sentence into the single best novel ever written about life at sea—and about sea-life:

But though, to landsmen in general, the native inhabitants of the seas have ever been regarded with emotions unspeakably unsocial and repelling; though we know the sea to be an everlasting terra incognita, so that Columbus sailed over numberless unknown worlds to discover his one superficial western one; though, by vast odds, the most terrific of all mortal disasters have immemorially and indiscriminately befallen tens and hundreds of thousands of those who have gone upon the waters; though but a moment’s consideration will teach, that however baby man may brag of his science and skill, and however much, in a flattering future, that science and skill may augment; yet for ever and for ever, to the crack of doom, the sea will insult and murder him, and pulverize the stateliest, stiffest frigate he can make; nevertheless, by the continual repetition of these very impressions, man has lost that sense of the full awfulness of the sea which aboriginally belongs to it.8

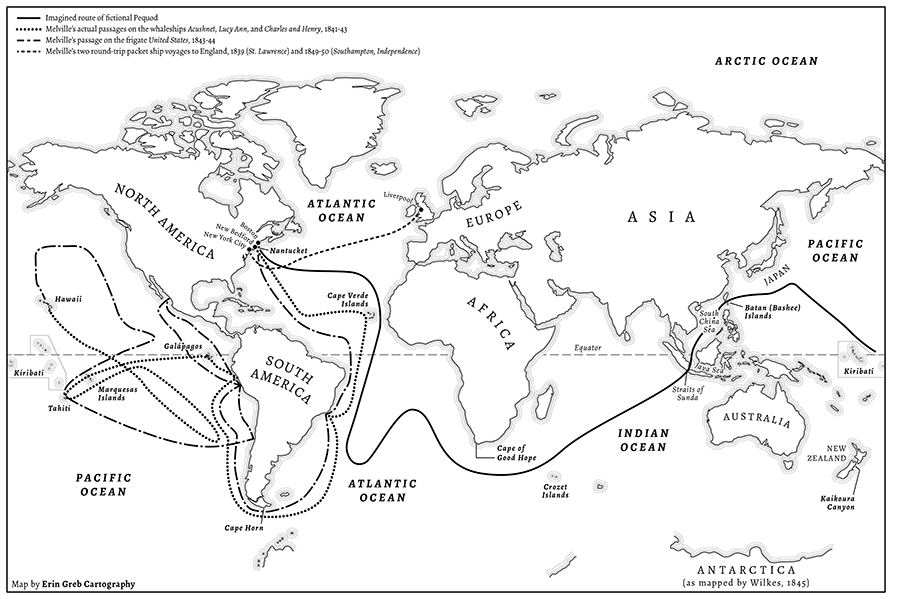

FIG. 1. Track of the fictional Pequod and Melville’s actual voyages before writing Moby-Dick.