Ch. 19

CORAL INSECTS

While all between float milky-ways of coral isles, and low-lying, endless, unknown Archipelagoes.

Ishmael, “The Pacific”

In The Tempest (1611), William Shakespeare wrote of coral within some of the most famous lines of sea literature in the English language:

Full fathom five thy father lies;

Of his bones are coral made;

Those are pearls that were his eyes:

Nothing of him that doth fade,

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.

Sea-nymphs hourly ring his knell:

[Burden, ding-dong.]

Hark! now I hear them,—ding-dong, bell.1

A spirit named Ariel sings these words as he deceives a prince into imagining his father drowned after a supposed shipwreck. Ariel sings that the dead king’s bones have been formed into coral in a strange, magical transformation: the image of a dead human now a part of the living deep.2 The year before he began to compose Moby-Dick, Melville engulfed all of Shakespeare’s plays for the first time while he lounged on a couch at his in-laws. He later used coral in his novel to also evoke death, deep, and magic.3

In “The Castaway,” only a few days after Stubb tricks his way into a handful of ambergris, Ishmael spins off Ariel’s song with his story of the tragedy of Pip, the young African-American steward. After Pip leaps out of a whaleboat a second time during a hunt, Stubb leaves him floating in the water. (Melville had once witnessed a nearly exact event with a sailor aboard the Acushnet.) “Man is a money-making animal,” Ishmael says to explain the officer’s cruelty. Stubb assumes the other boats behind him will rescue Pip, but those men end up sailing in a different direction chasing other whales. So the least powerful person of the Pequod floats entirely alone in the sea, foreshadowing Ishmael’s fate.4

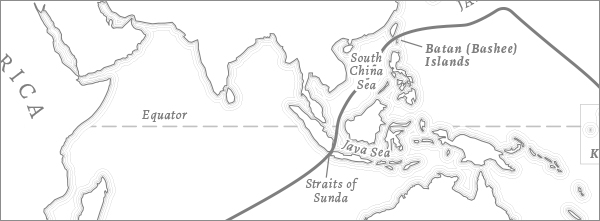

I read Pip’s submersion in the South China Sea as an imaginary sinking into his own loneliness of self and into the deepest of contemplation experienced within the outermost wilderness of the ocean, a view normally reserved for the sperm whale alone. This is the view Ahab thinks he wants to see. Pip is suddenly surrounded above, below, and in all directions by an ocean that is beyond human reach or influence. Ishmael describes:

The sea had jeeringly kept his finite body up, but drowned the infinite of his soul. Not drowned entirely, though. Rather carried down alive to wondrous depths, where strange shapes of the unwarped primal world glided to and fro before his passive eyes; and the miser-merman, Wisdom, revealed his hoarded heaps; and among the joyous, heartless, ever-juvenile eternities, Pip saw the multitudinous, God-omnipresent, coral insects, that out of the firmament of waters heaved the colossal orbs. He saw God’s foot upon the treadle of the loom, and spoke it; and therefore his shipmates called him mad.5

Pip survives. By chance, he is rescued by the lookouts of the Pequod. Yet he is rendered insane from the trauma. Just as in Ariel’s song, Pip begins to sound the death knell, “Ding, dong, ding!” He now performs as a Shakespearean wise fool, forecasting the ship’s destiny to sink and strike the rocks at the bottom, to go, as Fleece puts it, “fast to sleep on de coral.”6

As a castaway imagining his sinking into the deep, Pip does not hallucinate fish or whales or sharks, but instead “coral insects” and the colossal orbs that they spin, as if spiders, under God’s supervision. Melville’s choice of words and images here went beyond the connection to The Tempest. As early as the 1750s, the scientific community and then the general public understood that small animal-like polyps excreted skeletons to form the various shapes—fans, horns, and globes—that rose from the ocean bottom and grew on rock to form entire reefs. Naturalists also knew in Melville’s time that the brilliantly colored corals and the most enormous of these reefs were found almost exclusively in warm, relatively shallow tropical waters. Though known then to not actually be true insects, but colonial shell-building anemones, the common name of “coral-worms” or “coral insects” was in regular use, including by Dr. Bennett and Lieutenant Maury.7

Charles Darwin also used the common name of “coral insects” in his The Voyage of the Beagle. In 1836, shortly after the circumnavigation, Darwin wrote the paper that became the prevailing theory on the formation of different types of reefs. Most of Darwin’s ideas on coral reefs would prove true. He explained that atolls and other reef systems were formed by the subsidence of volcanic peaks and calderas: coral began to grow on top and on the edges of the land that was slowly sinking over millions of years. Aware of and interested in this public debate, Melville in his earlier novels alluded to the competing theories of reef formation, partly as satire, but also with seemingly genuine fascination about the “coral insect . . . this wonderful little creature” and their role in vast, geological systems that not only shaped reefs, but had implications for the formations of the Earth’s continents and notions of what we now call deep time.8

In Moby-Dick Melville crafted for Pip a vision of the deep with a coral bottom that swirled with the profound of the Divine. Two centuries after The Tempest, several works published during Melville’s time do much to reveal how mid-nineteenth-century ideas on faith and natural theology became associated with coral, and I want to tell you about three here in particular.

First, literary scholar Martina Pfeiler recently discovered the story “The Drowned Harpooner,” which appeared in the Nantucket Inquirer and was then reprinted in Graham’s Magazine in 1827. In this story a whaleman in the South Pacific, whom the author calls Jonah Coffin, is sucked under the surface by a line attached to a sperm whale and then dragged down into a sort of vacuum in the whale’s underwater wake. Jonah can breathe and see into the “bottomless profundities,” which includes “an extensive forest of coral inhabited by shapes indescribable.” Jonah is eventually rendered unconscious, then rescued alive after the sperm whale turns to come back up to the surface to die.9

Second, around the same time, a magazine article titled “Works of the Coral Insect” was a lesson in The First Class Reader, a popular book published for American schools. The anonymous author was astounded by the concept of the sheer vastness of the numbers of tiny coral organisms and the amount of time that would be necessary to create some of the islands in the Pacific and the Great Barrier Reef of Australia. This author believed, just as Emerson had lectured in “The Uses of Natural History” in Boston, that the reefs just below the surface were continuing to build upward, to provide still more land for humankind in the coming centuries. “These are among the wonders of His mighty hand,” wrote the author, “such are among the means which He uses to forward His ends of benevolence. Yet man, vain man, pretends to look down on the myriads of beings equally insignificant in appearance, because he has not yet discovered the great offices which they hold, the duties which they fulfil, in the great order of nature.”10

The third publication is a fascinating illustrated booklet published in 1847 in New York that is a compilation of the writing of contemporary scientists, titled Relics from the Wreck of a Former World, which sails along the same currents as Louis Agassiz and Lieutenant Maury, emphasizing even in its lengthy subtitle no difficulty aligning an Earth that is millions of years old with the Biblical teachings of the Christian faith, allowing for a vast range of extinct animals of “fantastic shapes” and “the most elegant colors.” Reverend Thomas Milner, a student of astronomy and a popular scientific author, was quoted at length. Milner wrote that the formations of coral reefs were perfect examples of “the power of Nature to effect her vast designs through apparently feeble and insufficient agents.” On the same page of his discussion of the “coral insects,” is the editor’s consideration of the concept that a grain of sand might hold its own ecosystem and that the distances of space and light might be unimaginable: “And when we reflect that if it were possible for us to attain to those distant spheres [stars], we should look, not on the limits, the blank wall of Creation, but only into fresh fields of Creation, Power, and Wisdom, we feel that our earth and all that it inherits is a mere speck in space, an atom amid the vast Universe.”11

Scholars don’t know whether Melville read any of these works, but if they were not a direct inspiration they reveal an aspect of the public perception of coral in an age that was still a century before underwater color photography and scuba. These publications and The Tempest show in part why Ishmael connects God and mortality with coral when pondering Pip’s philosophical plummet to the ocean’s depths. They also add to our reading of Ahab’s existential rages against that blank wall of the White Whale. For Melville and his contemporaries in the mid-nineteenth century, the coral reef was as sublime as the iceberg: stunning, unknowable, terrifically beautiful and yet fatally dangerous to the mariner. And perhaps most of all, coral was a symbol of the creative powers and brilliance of God.

Nor did Melville need any of these books or articles to feel spiritually moved by coral reefs. While in the South Pacific, he rowed and sailed over clear tropical waters that held these wonders. In French Polynesia, even right in Papeete harbor, he gazed, as he wrote in Omoo, “down in these waters, as transparent as air,” to see “coral plants of every hue and shape imaginable.” Melville had swum out to fringing reefs in the South Pacific. He described spearfishing around them by the light of torches. He might have even seen for himself specimens of the enormous Porites corals. Colonies of these corals off the South Pacific islands where he sailed and rowed can be truly “colossal orbs.” Scientists believe Porites can be some of longest living organisms on Earth. In the waters of American Samoa, for example, is “Big Momma,” also known as “Fale Bommie.” This colony is a forty-two-foot-wide globe and estimated at five hundred years old. The top of its dome is at a depth of thirty feet beneath the surface: full fathom five.12 (See plate 11.)

In 2017 researchers in the journal Nature declared that due to the effects of global warming, the entire Great Barrier Reef has died at an unprecedented rate: more than sixty percent of the coral, especially in the north, experienced extreme bleaching from the most recent high temperature event. This is more than six hundred miles of lifeless white coral that likely will not recover during my lifetime.13 My God.

Melville and his contemporaries watched and understood that invasive plants and animals were altering the Polynesian Islands, and that Americans and Europeans were corrupting and demolishing native cultures of “noble savages” in the South Pacific. Less understood then was that the Pacific Islanders themselves in their relatively recent migrations had vastly altered these islands, too, deforesting, spreading invasives, and hunting to extinction such species as the giant flightless moa (Dinornis spp.) in New Zealand. Yet I suspect that none of the nineteenth-century cultures, indigenous or colonial, could fathom that humans could ever influence the growth of coral reefs. In Omoo Melville retells part of a song from the elderly Tahitians:

“A harree ta fow,

A toro ta farraro,

A mow ta tararta.”

The palm-tree shall grow,

The coral shall spread,

But man shall cease.14

Read today, Pip floats over coral that now represents an entirely different type of bleached death. Pip is African American, but he could be an icon of a Native American or a Pacific Islander or any individual human reminder that social justice and environmental justice are inseparable. As the least powerful on the ship, a castaway, Pip is a symbol of those most vulnerable to anthropogenic climate change, depleted water resources, and the coastal pollution that is left in the wake of the hubris, the harpoons of petro-capitalism. We’re in the middle, of course, of a sea change of the very worst kind. It’s enough to make you lose your mind.