Ch. 26

SEALS

For not only are whalemen as a body unexempt from that ignorance and superstitiousness hereditary to all sailors, but of all sailors, they are by all odds the most directly brought into contact with whatever is appallingly astonishing in the sea.

Ishmael, “Moby Dick”

In late June 1794, Captain James Colnett’s ship Rattler sailed southbound off the coast of Chile, bound for home. They hadn’t caught that many whales, but at least no one had died of scurvy. At around eight o’clock at night the men on watch heard something over the side. Colnett described the scene later: “An animal rose along-side the ship, and uttered such shrieks and tones of lamentation so like those produced by the female human voice, when expressing the deepest distress as to occasion no small degree of alarm among those who first heard it.”1

Colnett explained that the cries of the animal were the closest thing he’d ever heard to “the organs of utterance in the human species.” The wails lasted for three hours and seemed to get louder as the ship sailed away. Colnett believed that it was a female seal that lost her “cub.” Or maybe a seal pup had lost its mother. For his men, however, the wailing of the animal “awakened their superstitious apprehensions.”

Nothing terrible happened directly after they heard the crying animal, but after rounding Cape Horn an enormous wave crashed over the back of the ship, filled the quarterdeck with water, smashed in some of the stern, and ruined the captain’s charts. By the time they neared St. Helena in the South Atlantic, not only was the Rattler “almost a wreck,” but a couple of their men were ill from scurvy and apparently still traumatized by the wailing sea creature. “We had one man indeed, who was literally panic-struck by the appearance and cries of the seal in the Pacific Ocean,” Colnett wrote. As they approached St. Helena, Colnett said that if they had spent another day at sea, the man would have died.2

For Moby-Dick Melville appears to have scooped up Colnett’s scene with the screaming seal, dipped the yarn in a little dark Gothic sauce, and plopped it right into his chapter “The Life-Buoy.” Ishmael explains that as they sail past a clump of small rock islands approaching the equatorial Pacific to hunt for the White Whale, the men hear “wild and unearthly . . . half-articulated wailings . . . crying and sobbing.” Some of the crew of the Pequod think the cries are from mermaids. The oldest sailor declares that the wails are the souls of drowned men. When Ahab clops up on deck with his peg leg, he, like Colnett, explains to his crew that the sound is only from seals.3

Ishmael then delivers an astounding perspective when read today: “Most mariners cherish a very superstitious feeling about seals,” Ishmael says, “arising not only from their peculiar tones when in distress, but also from the human look of their round heads and semi-intelligent faces, seen peeringly uprising from the water alongside.” The sailors in Moby-Dick find their superstitious fears about the cries to be confirmed. It was a bad omen—because a few hours later one of their shipmates falls from aloft and drowns. And when the men learn the next day that the crewmen of the Rachel are lost, the old Manxman attributes the seals’ cries to be those same departed spirits.4

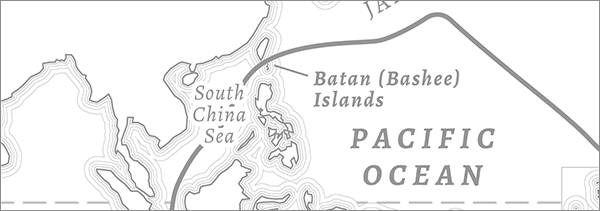

From a marine biology perspective, Melville squished his geography to help his fiction. Unless you imagine the final meeting with the White Whale on the far eastern side of the Pacific, near the Galápagos, there are no regular rocky island rookeries or haul-outs for marine mammals anywhere near the implied cruise track of the Pequod as it approached the equatorial Pacific. Along the cold-water coastline of Chile, Colnett and his crew perhaps heard the cries of a South American fur seal (Arctocephalus australis), but the safer guess is that they heard the larger, more common, South American sea lion (Otaria flavescens), another species of eared-seal. Both are found in that part of the world, feeding on fish and squid and hauling out on islands and coasts to mate and give birth. Biologist Claudio Campagna, who was part of a recent study of the vocalizations made by South American sea lions, read Colnett’s account for me and explains: “It could have been a sea lion female. Sea lion females call their pups with sounds that really may be described as a human female in distress.”5

From an environmental studies angle, Ishmael’s comments that most sailors have a superstitious sympathy for seals is surprising for the time period, even with Colnett’s narrative in mind. Bashing and hunting seals, sea lions, walrus, and sea elephant for oil and furs was big business and a sort of little brother industry to whaling. Hundreds of vessels in the 1800s did both. At some point during his travels at sea, Melville surely saw and heard seals beside his ship, especially near the Galápagos, even though by then large-scale hunting of pinnipeds at any and all accessible rookeries in the Southern Ocean and South Pacific had been exploited for decades. The whalemen would often eat the meat of the pinnipeds they captured. Nineteenth-century mariners’ accounts seem more disgusted and afraid of pinnipeds, rather than seeing any of the human identity or intelligence in their big eyes and whiskers that Ishmael describes, or even his comparison in an earlier scene in Moby-Dick in which Ahab is like a proud, bull sea lion presiding over the cabin table. For example, author George W. Peck sailed along the same coast of Peru and wrote in 1845 that he believed the South American sea lions to be “unnaturally hideous” and “the compelled agents of some diabolical spell or inevitable doom.” Peck described the sea lions regularly swimming out to ships: “their breathing is always like sobbing; their cries are wails.” Especially in the Arctic, whalemen were often forced to kill these marine mammals to supplement their oil stores or to feed themselves. A few did sympathize with these pinnipeds, as Ishmael implies. For example, Mary Brewster aboard the whaleship Tiger explained that a sailor stopped short of killing a walrus alongside the ship because “it looked so innocent.” But the whalemen still regularly harpooned and clubbed them to death. Adeline Heppingstone, the captain’s daughter aboard the New Bedford whaleship Fleetwing, once wrote of a seal she watched over the rail: “One dear little fellow came close alongside of us and looked up into my face.” Heppingstone didn’t seem to mind the killing, though, because “the skins make warm clothing for them.” In Moby-Dick the harpooners Queequeg, Tashtego, and Daggoo barely consider the pinnipeds at all: “the pagan harpooners remained unappalled” by the screaming seals. In the same way they were unmoved by the giant squid, experienced at sea like Ahab, these men do not make any anthropomorphic connections to the sound of these animals.6

So Ishmael’s story about the superstitions that Yankee mariners had about seals, because of their human-like faces, suggests that there actually has not been, as is often theorized, an entire cultural shift in the way Americans thought about smaller marine mammals—the idea that everyone hated all marine mammals until the mid-twentieth century. Perhaps there really is something hardwired in some of our affection for animals that look or act like humans, as Ishmael spoke of his huzzah porpoises—or maybe there is something unique to seals and their long history in selkie stories. That is, if we don’t need seals and sea lions for our livelihood or have not been taught to eat them. To jump-start advocacy and attention to the oceans and coasts, environmental activists in the 1950s chose animals such as baby seals and penguins and dolphins, which each had identifiable human-like behaviors or expressions. The 1964 film footage of the clubbing of fluffy, white, baby harp seals on the ice of the Gulf of St. Lawrence made international news with profound, immediate impacts. Activists for environmental and animal-rights movements found an ideal symbol in these baby seals. Meanwhile, the movie Flipper (1963) and then the television show of the same name had been portraying a clever dolphin version of Lassie, the dog.7

Ishmael recognizes a century and a half earlier that you’d have to have a stone heart to dislike dolphin play. The perception jump that had to come, which Moby-Dick advanced in 1851, although often toward other ends, was that large whales, without overt human features or human-like behaviors, deserved empathy and attention, too. After the popularization of seals and dolphins, it was not old age or sentience, but the vocalizations, ironically, that next built sympathy for the large whales in American popular culture. These were not the human-like moanings of sea lions, but the first underwater, exceptionally otherly, organized “songs” of humpback whales, reproduced by Roger Payne (a big fan of Moby-Dick), who distributed the little records into every single copy of the January 1979 issue of National Geographic magazine.8