4. UNDER ASSISTANT WEST COAST PROMO MAN

1963

If you want to make rock and roll your career, you have to have a certain equilibrium between your personality and your ego and your physical makeup—the three things you have no control over. Then you have to have a certain balance to be able to deal with anything that’s thrown at you. And anything you throw yourself into, you better get yourself out of.

KEITH RICHARDS, from an interview with Bill German, 1987

Keith and Mick couldn’t possibly have chosen anyone better as their next catalyst than Andrew Loog Oldham. A skinny nineteen-year-old mod who had worked as a madcap publicist for the dress designer Mary Quant and was a part-time PR man for the Beatles’ manager, Brian Epstein, Oldham was a twenty-four-hour-a-day bag of nerves who saw himself as a Phil Spector, the British version of the “teenage tycoon shit.” “He was calculatedly vicious and nasty, but pretty as a stoat,” wrote George Melly. “He had enormous talent totally dedicated to whim and money.” According to Richards, he was “a fantastic bullshitter and an incredible hustler.” His mind was best described by his favorite book, A Clockwork Orange, as “a nice quiet horrorshow.” Loog rhymed with droog. According to his girlfriend, Sheila Klein, “He was very entertaining, very funny in terms of performing. He would perform to an imaginary audience—or a real one—all the time. Andrew was on twenty-four hours a day.” “We just had the same basic desire to do something—a hustling instinct,” Oldham recalled. “I wasn’t coming on with a cigar and a silk suit going, ‘Listen, kids.’ I was the same age as them. We talked the same language.”

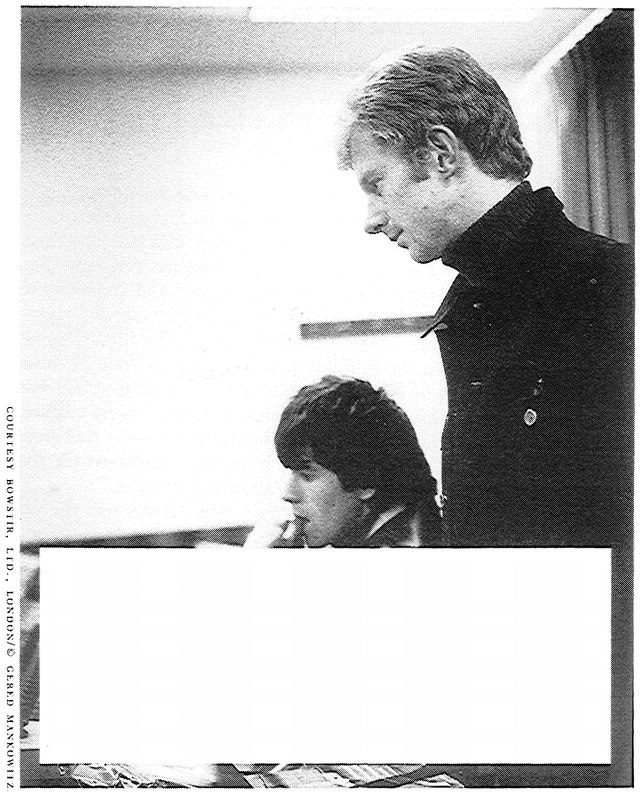

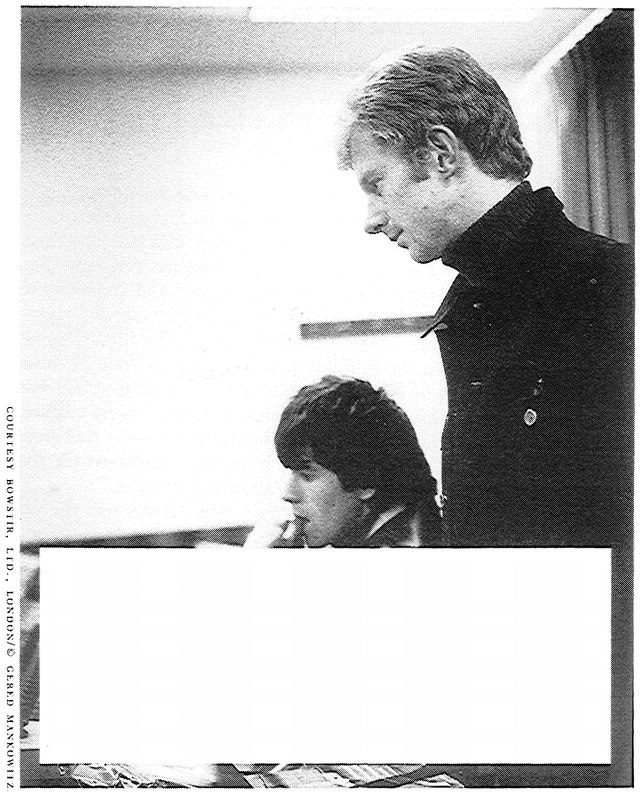

In May 1963 Oldham became their manager. The Stones had made a handshake agreement with Giorgio Gomelsky that he was their manager, but they were impatient and found his vision limited. Gomelsky was extremely upset when he found out they had screwed him. The Stones, according to Jagger, felt they were too good and important to let things like that get in their way. The photographer Gered Mankowitz, who would become friends with Oldham and the Stones’ semiofficial photographer in the midsixties, saw Andrew as “one of those people who is capable of bringing people together, a catalyst. He was very stimulating, very funny. Able to be incredibly cruel. Very cutting. He had an enormous talent for hearing the right thing—he had great ears—and understood the nature of the business, understood the nature of media as it was then. He was an extraordinary bloke.”

“I knew what I was looking for,” Oldham said. “It was sex, the sex that most people didn’t realize was there. Like the Everly Brothers. Two guys with the same kind of face, the same kind of hair. They were meant to be singing together to some girl, but they were really singing to each other.”

During the summer of 1963 Oldham cut into the band like a poker player shuffling his deck. Ian Stewart would have to be flushed out because “he didn’t look right for the part.” Jones would have to be relieved of his illusion that he was the band’s leader. Jagger would be featured as the front man and sex symbol, and Richards had to cut the s off his name because Keith Richard looked more pop. For the next fourteen years, Keith would be known by this stage name. Ian Stewart agreed to stay on as their road manager and continued to play on their records and sometimes on stage.

RICHARDS: “He was always the perfect counter for all the bullshit we had to go through. This is where Brian starts to realize that things have gotten beyond his control. Before this, everybody knows that Brian considers it his band. Now Oldham sees Mick as being a big sex symbol, and he wants to kick Stu out, and we won’t have it. And eventually, because Brian had known him for longer than we, and the band was Brian’s idea in the first place, Brian had to tell Stu how we’d signed up with these people, and how they were very image-conscious, and Stu didn’t fit in. If I’d been Stu I’d have said, ‘Fuck it, fuck you.’ But he stayed on to be our roadie, which I think is incredible, so bighearted.”

That summer Oldham fashioned the Stones into a pop-art band. Sizing them up like a bunch of storeroom dummies, he snipped here and tucked there; he pinned down one little hem while lifting up another. He insisted that they wear identical outfits, like the Liverpool groups, with jackets designed to accentuate their buttocks. The results? Within two months, Oldham had transformed six funky-looking R&B musicians into five fatuously grinning “teenagers” in bumfreezer jackets who might just as well have been called the Monkees. According to Richards, they agreed to Oldham’s changes because they had been to a Beatles concert in London that April. “By now we were star-struck, every one of us. The Beatles had seen us play, and we’d been to see them at the Albert Hall, and we’d seen all the screaming chicks, the birds down in front, and everybody couldn’t wait to hear the screams.”

In September 1963 Oldham arranged for Richards and Jagger to move out of Edith Grove and into a somewhat better flat in the Brondesbury section of North London, at 33 Mapesbury Road. The end of Edith Grove signaled the end of an era. Jones moved in with the parents of his girlfriend in nearby Windsor. Shortly thereafter Oldham, claiming that his mother had thrown him out, turned up on Richards and Jagger’s doorstep with the immortal line “Can I crash at your pad?” At nine pounds a week, the Mapesbury Road apartment consisted of two rooms overlooking the street on the second floor of the building. The bathroom in the hall was communal. The apartment had a distinctly different atmosphere from the one at Edith Grove. With Jones out of the picture there was less madness. Keith, Andrew, and Mick were intent on doing the job at hand. There was little time to sit around making faces at each other or recording bathroom performances. “It was,” recalled Oldham, “rather a quiet place. Half a bottle of wine in the flat was a big thing.” Jagger found Richards a puzzling roommate: “He was very untidy and very forgetful and I still don’t know what he was thinking about at any time, even though he was one of my closest friends. He was so awful in the morning, but the rest of the time he was so lively.”

Although the landlady at Mapesbury Road, Mrs. Yalouris, remembered them as very nice boys who never caused any trouble or made noise, Oldham’s abrasive personality was outrageous to the British music business. He might come into the office of a very proper gentleman such as the chairman of Decca Records, Sir Edward Lewis, to discuss a contract and suddenly put his feet up on the desk! On another occasion, he became so impatient in a traffic jam he leapt out of the car and ran across the roofs of all the stalled cars in front of him. Oldham’s irreverent make-it-up, fuck-everybody, let’s-just-do-it attitude electrified Richards and Jagger and summed up British rock and roll in 1963. “The resistance to the band in the music business was incredible,” Oldham said, “but we managed to turn that into a positive factor.” They did it primarily by scaring people they despised with the callous, terrifying attitudes of the teenage gangs in A Clockwork Orange. Their nasty laughter inspired hatred and fear in the old men who ran the companies.

RICHARDS: “There was a time when Mick and I got on really well with Andrew. We went through the whole Clockwork Orange thing. Brian never liked Andrew, but he knew that Andrew could help the band more than anyone else. Andrew pulled the right strokes as far as the public relations were concerned, at just the right time. And it worked like clockwork. Nothing was planned. It just fell into place and Brian was resigned to the fact that Andrew was a necessary part of the general noncommunicativeness.”

The power base in the band shifted to the Richards-Jagger-Oldham triangle. As Oldham saw it, they were bonded together as much by their work as by their need to keep themselves in the public eye. For them there was no private life. Everything they did was dedicated to the creation of the Stones.

Oldham’s financial backer, Eric Easton, inspired Keith’s affection because he had played the organ in the dying days of British music hall vaudeville in the 1950s—at the same time as his beloved Crazy Gang. As soon as he had signed them, Easton launched them on a series of one-nighters in ballrooms and clubs in the hinterlands of London that was their first step on the road that would take them out of the smoke and into the glare of the world stage.

RICHARDS: “It was difficult for the first few months. The British end of rock and roll was run by these strong-arm promoters, which meant that you played three or four ballrooms a night, forty-five minutes on stage, get off, jump into the car, you’re driven to another one, back to the other one for the second show, and you wear these shitty little suits that they advance you the money for and charge you later, plus wear and tear, and if you don’t make the gig, they break your fucking leg. [Heavy accent:] ‘Because Moe is not going to stand for any fookin’ nonsense, my boy, I’m telling you. Like, this is Lou, this is my bruvver Johnny; don’t ask this bloke’s name.’ I kind of lived in dread of having fingers broken. It’s never been a sweet business.

“We were known in the big cities, but then you got outside into the sticks, they don’t know who the fuck you are and they’re still preferring the local band. That makes you play your ass off every night, so at the end of two-hour-long sets, you’ve got them. That’s the testing ground, in those ballrooms where it’s really hard to play. The local youths in places like Wisbech had heard of the Rolling Stones but had no idea what to expect. To start out with, most of them, especially the boys, just gawked. You could sense the hostility from the guys. The chicks were just amazed. They were trying to make up their minds. By the end we always had them, by at least three or four numbers. No matter where we played we had them. They were always bopping about.”

At the end of September 1963 they embarked on their first national tour. Incredibly, the headliners were some of their greatest heroes and biggest influences: Bo Diddley, creator of the seminal “hambone” rhythm, the Everly Brothers, and Little Richard. If the Stones had wanted to go to a rock and roll graduate school, they couldn’t have hired better instructors.

For Keith, playing on the same stage as Little Richard was “the most exciting experience of my life.” Watching Bo Diddley and the Everly Brothers was a nightly education in how to build and hold an audience. Richards and Jones were particularly drawn to Diddley, literally sitting at his feet night after night talking and playing music.

BO DIDDLEY: “It was my first engagement in England. Me, Brian, and Keith became jug buddies; what we call jug buddies is that we drink out of the same jug. They were nice to me then, like brothers. I don’t mean black brothers, I mean brothers period. Togetherness. And it was really unique. These people showed me hospitality of another country.”

Touring clarified their image. Keith was particularly pissed off about having to wear the outfit Oldham had chosen for the band, which reminded him of his school uniform. He quickly destroyed his jacket by dumping chocolate pudding and whiskey on it or leaving it on the dressing room floor.

RICHARDS: “It’s funny people think Oldham made the image, but he tried to tidy us up. Andrew wasn’t ahead of us in that respect from the beginning—the press picked up on us only when we’d personally got rid of those dogtooth jackets and the Lord John shirts. It was only then that Andrew realized the full consequences of it all and got fully behind it. After that the press did all the work for us. We only needed to be refused admission into a hotel and that set the whole thing rolling. Andrew exploited our image. He wasn’t totally on the right track. He nearly fucked us up with those jackets.”

Oldham now realized that the low road was the only road. Between the fall of 1963 and summer of 1964 Oldham, aided by the times and the Stones’ talent and enthusiasm, performed nothing short of a miracle of exploitation. Seizing upon the fact that the Beatles had achieved their extraordinary success by turning themselves into acceptable teen images with neatly combed hair, suits, and ties, Oldham hit upon the idea of creating the Stones as their mirror images. It is hard to imagine how vitally important clothes were in England in the early sixties. They were in a sense the only political statement the masses could make. Thus the Rolling Stones only had to enter a restaurant with their long, unkempt-looking hair, tight pants, which accented the crotch and ass, and without ties to literally cause a sensation in the following day’s newspaper. In retrospect it was an easy game, but at the time they were inventing a new breed, and Oldham’s intuitive sense of soundbites was ahead of its time. His greatest coup was to fashion a series of sloganlike statements that alienated the old and commanded the adoration of the young. Billing the Stones as the ugliest group in Britain, he unleashed the polarizing challenge “Would You Let Your Daughter Go Out with a Rolling Stone?,” which summed up their approach. “People say I made the Stones,” Oldham recalled. “I didn’t. They were there already. They only wanted exploiting. By the time I got through planting all that negative publicity, there wasn’t a parent in Britain that wasn’t repulsed by the very sound of their name.”

Oldham hit on the axiom “The Rolling Stones are not a band so much as a way of life.” It was the line that best described the band’s existence, as well as its impact.

RICHARDS: “I reckon there are three reasons why American R&B stars don’t make it big in Britain. One, they’re old: two, they’re black; three, they’re ugly. This image bit is very important. It was the image they wanted. We were very hip to the image and how to manipulate the press. When people made these kinds of irresponsible remarks it just drew the fans more firmly to our side.”

At the center of the music and hype was the button of sex. On that first national tour Richards later recalled that he could feel the energy building night after night until it finally exploded in “a sort of hysterical wail, a weird sound that hundreds of chicks make when they’re coming.... They sounded like hundreds of orgasms at once. They couldn’t even hear the music, and we couldn’t hear the music we were playing.”

RICHARDS: “Maybe it had to do with World War II or some other social and political thing, but teenage girls needed that sort of frenzy. It was like a mating thing. Surprised as you are that chicks in Sheffield and Doncaster are like going berserk over you, you have a little bit of room to maneuver because for a while only you know that something is going down. It happened so fast that one never had time to really get into that thing, ‘Wow, I’m a Rolling Stone.’ We were still sleeping in the back of this van every night of the most hard-hearted and callous roadie I’ve ever encountered, Stu. From one end of England to the other in Stu’s Volkswagen bus. With just an engine and a rear window and all the equipment and then you fit in. The gear first, though.”

The writer Nick Kent, who would become a major figure in promoting Keithmania in the 1970s, first saw the Stones perform in Cardiff when he was twelve years old.

NICK KENT: “The Stones were second on the bill that night, but you could see the whole audience change when the Rolling Stones came on. These young girls just became wild and violent and made this weird, bestial sound. It was an electrifying experience. I had front-row seats and this girl from the third row threatened me with a stiletto so I immediately sat in the third row.

“After the show I went backstage to meet them. You have to understand the Stones looked so weird that all the girls were frightened of them and they were particularly frightened of Jagger because he had those lips and you didn’t see guys like that with long hair in early 1964. Brian Jones was the most nicely middle class, and there were like five girls backstage who were totally enchanted but also very frightened. They all went to Brian, but they were looking at Jagger, who was standing next to them with the attitude, ‘OK, talk to me. What you talkin’ to that cunt for?’ Meanwhile Keith Richards had passed out on the sofa with a bottle of beer in his hand and I went over to get his autograph and he belched in my face.”

RICHARDS: “We knew we had become successful when we did that first tour. You know a month or two in front of anyone else that it’s happening because you’re there every night watching the way the audience is reacting and suddenly there’s little girls on the street dressed in their best clothes. I was nineteen when it started to take off and just an ordinary guy—chucked out of nightclubs, birds’d poke their tongues at me, that kind of scene—and then suddenly, Adonis! And you know this is so ridiculous, so insane. It was really a bugger. It makes you very cynical. But it’s a hell of a thing to deal with. It took me years to get it under control.”

As lain Chambers pointed out in Urban Rhythms, “As the shock effect of parading a blatant male sexuality (although frequently crossed with the contradictory signs of long hair and ‘effeminate’ dressing) sank in, existing conventions were everywhere affected. Proposing music as the direct extension of a sexual body, white R&B became a potential instrument of cultural revolt. The translation of black R&B and soul into white pop thus involved—particularly in the Stones’ case—an explicit sexual strategy intent on dismantling the prevalent sentimental and romantic ties that dominated pop and Tin Pan Alley.... The contradictory musical and cultural outrage represented by the Stones was destined to transform them, first in England and subsequently in the United States, into the decade’s sonorial metaphor for white metropolitan youth rebellion.”

The rivalry for leadership that had begun with the arrival of Oldham continued. Jones felt the slow transfer of power to Jagger.

RICHARDS: “You don’t realize it on stage, but the strength of the spotlight on the singer is so much brighter than that on the rest of the musicians. The focus of attention is paid so much on the singer that no matter how much you want to upstage the singer, you can’t possibly do it. Brian really got off on the trip of being a pop star. Suddenly, from being very serious about what he wanted to do, he was willing to take the cheap trip. And it’s a very short trip. He was a contradiction in blond. He was the only guy in the world who thought he could take on Mick as the head onstage personality. ‘All the chicks liked me better than Mick.’ You know, one of those confidences. And it went on for so long.”

As Bill Wyman pointed out in his aptly titled memoir Stone Alone, “You had to be tough to be in the Stones.” Keith and Mick kept the others under submission by spritzing them with acerbic gibes. While they failed to penetrate Wyman, they began to pulverize Jones. Keith and Mick called him Mr. Shampoo because of his obsession with clean hair. Both did caustic impersonations of his defects—his short legs, which he camouflaged with high-heeled boots, his bull neck. “The faint-hearted or ultra-sensitive would not have stood the gibes that poured from Mick and Keith,” Wyman wrote. “They had to have someone to poke fun at, not always in a humorous way, often spiteful and hurtful. They had to have a scapegoat or a guinea-pig.” “Keith is the kind of guy you should leave alone,” explained Charlie Watts. “He is the classic naughty schoolboy, the sort of guy I knew at school who hated the head boy. And I loved Keith because of that.”

Oldham might have seen the boys as the droogs in A Clockwork Orange, but they would have fit better into William Golding’s Lord of the Flies. Like the Stones, the novel’s marooned English schoolboys established a dominant order and then split into competitive, lethal units. Seeing the chink in Brian’s armor, Oldham delivered a decisive blow by revealing during the tour that Jones was receiving five pounds a week more than the others. “Everybody freaked out,” Richards recalled. “We said, ‘Fuck you!’ ” As a result, Brian Jones lost his position as leader of the band.

“Brian got exactly what he was asking for,” Stewart explained. “He’d been an asshole to everyone.”

One musician who toured with Richards recalled that Keith already displayed the behind-the-scenes leadership qualities that would emerge publicly in the 1970s: “He knew the power he had, but he was quiet and reserved. They were acting out their characters in those days and their characters really became what they are. I watched him on tour a lot and he never really strayed away from being Keith Richards. Keith doesn’t ever really change. He’s the same guy all the time.”

Richards described his first year on the road as “a hard school.” When he started he told Beat International that he “used to wish I could have had a screen between me and the audience. I just wanted to play, not put on any showmanship.” Nevertheless, he soon developed a style that became a model for guitar players on both sides of the Atlantic. Grabbing his guitar and threading his way over tangled wires through backstage crowds to his position, Keith would raise his hand above his head, ready to hit the opening chord as the curtains parted. He would play with his back to the audience as he focused on Charlie, or he might crouch down to hit a particularly intense chord. Occasionally he’d break into a maniacal grin and run backward, or dart across the stage behind Mick to interact with Brian. All of the gestures were executed with an entirely appropriate dramatic flourish. In this way, Richards invented an image of the guitar player that has been imitated ever since. Pete Townshend was among the first to admit, “I pinched my arm-swinging movement from him.” “Keith really is a kind of selfcontained performer,” Albert Goldman commented. “His moves are invariably graceful, well struck, and he makes sense of the body rhetoric that is the most classic, most fitting to a guitar rocker. He’s the discus thrower of rock. He’s perfect.”