6. AS TEARS GO BY

1963-1965

Mick and Keith were incredibly close and very seldom argued as far as I could tell. Andrew was intense, jumpy, nervous, neurotic—“Let’s do it, let’s be, let’s run, let’s do it!” Keith liked Andrew and the three of them, Andrew, Keith, and Mick, had a good time.

LINDA KEITH, from an interview with VictorBockris, 1989

Just as Richards and Jagger had taken everything they could from Jones, since moving to Mapesbury Road they had concentrated on learning everything they could from Oldham. One day in the summer of 1963 Andrew informed the astonished duo that they had to start writing their own songs. “If you take your favorite parts from three hit songs and combine them you’re bound to get a hit,” Oldham kept saying.

RICHARDS: “For me, definitely the greatest contribution Andrew made was locking me and Mick in the kitchen for a day and a night and saying, ‘I’m not letting you out until you got a song ....’ He put it to us: ‘You’re gonna be dependent upon other songwriters, other people, for all the material you need! From now on you’re gonna be more and more dependent. If you get used to that, you’ll never get any original material, so come on, let’s get it all together. Anybody can write a pop song. I’ll lock you in the kitchen!’ It was a shock to us. We’d never even thought about it. Andrew literally forced Mick and I to start writing songs. My first reaction was ‘Who do you think I am, John Lennon?’ At that time, for me, songwriting was somebody else’s job. My job was to play guitar and that’s what I wanted to do. I didn’t think I’d be a songwriter any more than I’d be a nuclear physicist on the side. It was a different area of operation. But Andrew showed me, and what I firmly believe is if you can play an instrument you can write a song. Andrew presented the idea to us, not on any artistic level, but more money. That was the pressure of business. That was a very astute observation of Andrew’s. It was very obvious once he put it to us.”

It was a year before Richards and Jagger wrote anything stamped by their dual character, but they found success almost immediately in marketing their original songs. Another Decca artist, George Bean, recorded a Jagger-Richards single in 1963. Gene Pitney’s version of an early effort, “That Girl Belongs to Yesterday,” went to number seven on the U.K. charts. “Tell Me” was on their first album and was their second single in the U.S., where it went to number twenty-four.

That Richards and Jagger could write together soon became a given. After they tried it a couple of times, it was obvious to both of them that this was something they could do together, and they quickly staked out their positions. “Keith always had a lot of talent for melody from the beginning,” Mick said. “Everything, including the riffs, came from Keith.”

The transition was hard at first. “We were making the same mistake as most white kids who get hung up on the blues,” Keith said. “We’d become elitist, although we used to despise the so-called purists. So we needed to reconcile all this with our own past and where audiences were at. And everything we’ve done since then has been a reconciliation.”

They found their voice with two Stones classics written in the summer and fall of 1964. “As Tears Go By” and “The Last Time” revealed the soft and hard sides of Richards and Jagger and staked out the territory of teen angst they would make their own. While Keith and Mick had been desperately failing to come up with some Rolling Stones music, a directive from Oldham to do something opposite finally ignited their creative chemistry. In an attempt to branch out à la Phil Spector, Oldham planned to launch onto the pop scene an angeliclooking convent-school girl named Marianne Faithfull. He asked Jagger and Richards to write a song for her that would conjure up brick walls, high windows, and no sex, and was credited as cocomposer. “It was,” noted one critic, “their first real song in the sense that it sprang wholly from within themselves, stamped unmistakably with a shared character.”

Marianne Faithfull, who would become a powerful influence on the Richards-Jagger collaboration, had a keen perception of the Stones when she recorded the song in the summer of 1964. On the one hand she found them “horrible people—dirty, smelly, spotty.” The recording itself, she said, was “all done in half an hour ... it was very strange because they wouldn’t speak to me. There was Andrew and Mick and Keith and friends and I just went in and did it. I was quite staggered that they wouldn’t even give me a lift to the station.”

On the other hand, she soon found herself drawn to Keith. “I was too scared to go up and talk to Keith, of course. And he was much too shy to talk to me. But I liked him. Very much. Keith was a sort of insecure person with a very reflective, intuitive side, which is a very important part of being an artist, and that’s what you have to have, that ability to sort of just go in. And that’s what I saw. What I felt was just a sort of natural respect. And then when I knew him I could see that side to him in knowing him and seeing him work and the songs he would write, and the way he had a much more sensitive understanding of music. And I think that’s why he liked Brian Jones—they had that sort of thing in common.”

In August their second U.K. extended-play 45 went to number seven on the singles charts. By September, Faithfull’s recording of “As Tears Go By” was in the British top ten and Richards and Jagger were being heralded as the next Lennon and McCartney. Lest there be any doubt of the value of Oldham’s contribution, one critic who used the pseudonym Jimmy Phelge wrote: “Had it not been for Andrew Loog Oldham’s imagination, perspicacity, and sheer bloody-mindedness, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards would not, in all probability, have ever gotten around to writing together. In which case the Rolling Stones would never have made the quantum leap from snotty South London blues combo to the Greatest Rock & Roll Band Who Ever Drew Breath. By becoming the catalyst (or was it midwife) at the birth of the Glimmer Twins (as they would later become known) he’d radically and irrevocably re-shaped the Stones’ destiny—having effectively and irretrievably banished Brian Jones to a supporting role and restructured the power base and the rhythmic dynamics of the band in the process.”

Both men were surprised by their success. “Something clicked,” Richards recalled. “We didn’t shout about it much in the early days. It was a good partnership. We never seemed to be short of ideas. We both happened to like the feeling of actually creating something.”

“We never dreamed of doing that ourselves when we wrote,” said Jagger. “It’s fun as long as you can work with someone to bounce off. You can’t bounce off your old lady like you can your songwriter.”

Actually, the Stones had two writing arms. Apart from the JaggerRichards credits there were also group compositions registered under the pseudonym Nanker Phelge, a name that combined Brian’s term for the disgusting faces he and Keith used to make and the surname of their old Edith Grove catalyst.

Songwriting was also one of the more lucrative pursuits in the music business. Not only does the songwriter earn more royalties than the other members of the band, but selling the publishing rights to the song is the only way to earn any real money in the early days of a career. According to Bill Stephen in Musician magazine, “The publishing deal can be more important than the record deal and, should you have a hit tune, far more lucrative over the long run, particularly if your song gets covered by a famous artist.” By now Richards was banking more money than he had time to spend.

On returning to England from a second U.S. tour in November 1964, the Stones released the follow-up single to “It’s All Over Now.” Almost as if they knew they were about to take off into an altogether different realm and wanted to pay one last homage to their roots in Chicago, they chose an obscure, unassailably noncommercial Willie Dixon number, “Little Red Rooster,” characterized by Keith as a “pure barnyard blues,” rather than plunging ahead with the most commercial sound they could find. Much to the surprise and delight of all concerned, it leapt onto the U.K. charts at number one (a feat previously performed only by Elvis, and Cliff Richard).

RICHARDS: “Singles were all-important then. You put yourself on the line every three months and therefore it had to be distinctive or else. At that time, releasing ‘Little Red Rooster’ was our distinction, the only way we could set ourselves apart from everything else that was going on.

By that time their career was going global. “Tell Me” was number one in Sweden and Denmark. “Not Fade Away” was number one in Greece. “It’s All Over Now” was a top-ten hit in Denmark and also reached number one in Germany, Holland, and Sweden. All their records were selling rapidly in most European countries and the Commonwealth, and the American market was opening up.

As “Little Red Rooster” held the number-one spot, Keith and Mick hashed out “The Last Time” at Mapesbury Road, their first song that felt good enough to produce as a Rolling Stones single in Britain. “In retrospect, Mick and I learned really quickly,” Keith said. “It seemed a long time at the time—sort of, ‘Do we have the balls to give this to the rest of the boys to play?’ Until we came up with ‘The Last Time.’ Then we said, ‘Yeah, this one we won’t be ashamed of giving to the rest of the Stones, so let’s try this for a single.’ ”

“My vision of Keith is that he was constantly strumming the guitar, but it wasn’t to find the music that was within himself—in a way, almost, it was to find the music that was out there,” said Linda Keith. “It evolved all the time, it was moving ahead.” Meanwhile, they continued to produce successful albums of mostly R&B covers with a few Jagger-Richards and Nanker Phelge compositions shoehorned in. In December 1964 their second U.S. album, 12 x 5, went to number three.

Keith was living at full throttle, rocking around the clock, playing music, attending parties, looning about with Andrew, running amok. The first indication that he had started staying up for days at a time without sleep came on November 19 when he collapsed after performing on the British television show Ready, Steady, Go! According to Wyman, “He hadn’t slept for five days and was thoroughly exhausted.” But most of the time he had real stamina, at least real enough to allow for continuing musical growth in a time of intense activity. In 1964 the Stones had done five British tours, two American tours, and two European tours. In mid-December 1964, “Heart of Stone,” composed by Jagger and Richards, became the group’s fifth U.S. single. It went into the top twenty. Richards had never imagined that his music could be popular in America. When it was, he found it ironic that rather than buying the rock and roll songs, the fans preferred the slow ballads.

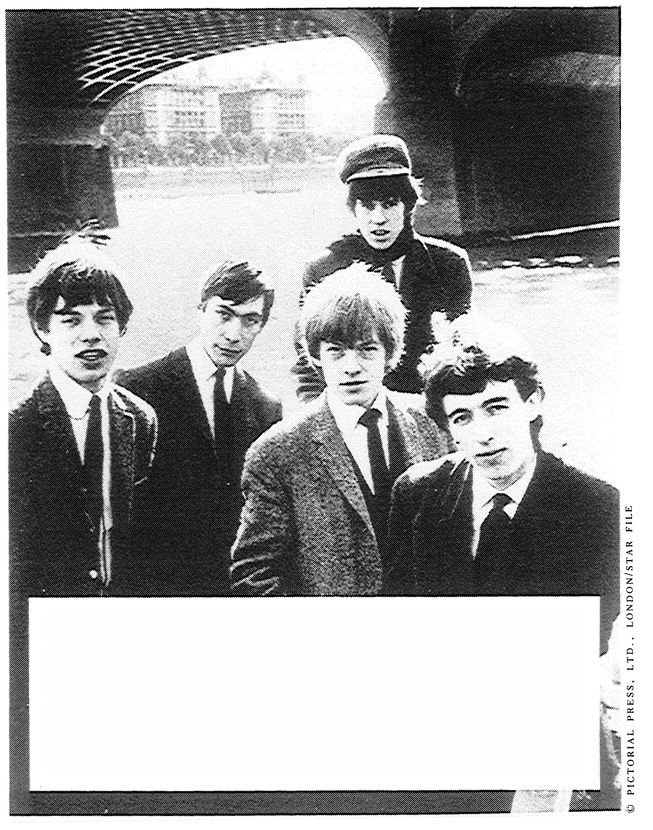

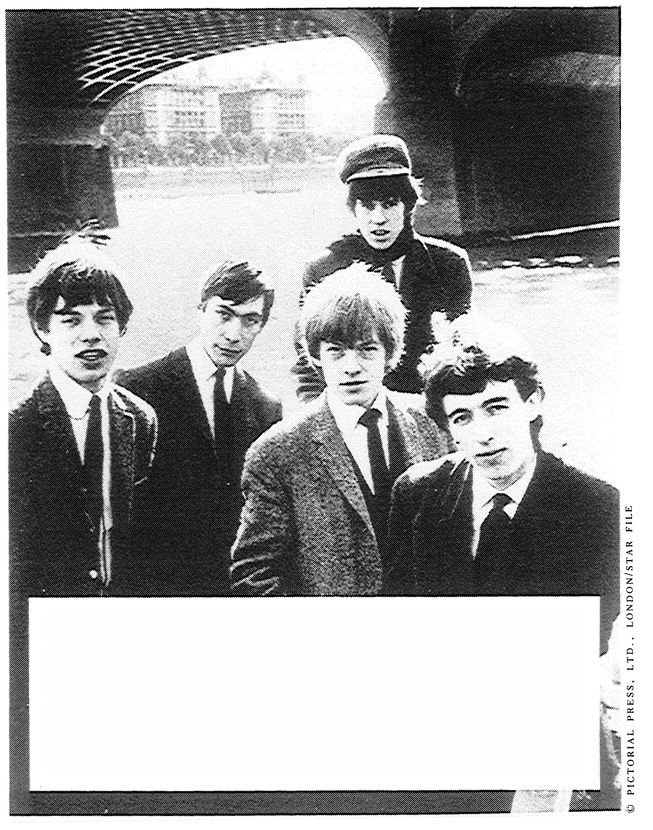

In January 1965 their second U.K. album, The Rolling Stones No. 2, went to number one. Keith’s acne-scarred face, which was featured front and center surrounded by the brooding amphetamine glares of the group, was seen as a purposeful Oldham stroke that only made the fans more empathetic. “I’m glad I’m not the only person in the world with pimples,” wrote one. “Just goes to show I guess even stars get spots. So you’re human after all!”

They recorded “The Last Time” on February 17 and 18, 1965, at RCA Studios in L.A. “I’d say ... maybe sixty to seventy percent of our output was recorded in the States during 1964, and by 1965 just about everything was done there—either in L.A. or Chicago,” said Keith. Dave Hassinger, who engineered the sessions, noted that Jagger and Richards made all the decisions in the studio—the other three were only peripherally involved. Oldham, too, deferred to them.

The hierarchy in the studio had reached its final form. Keith and Mick were in charge. By now Keith’s position as the band’s producer had become an unspoken rule. As Hassinger described it, after a playback everybody looked at Keith, and if he was smiling they knew they had a good take. There was never any discussion. Behind the scenes, however, everything was not so copacetic. Wyman complained that Jagger and Richards had a monopoly on songwriting credits and, in turn, the lucrative royalties.

“The Last Time,” released in early March, was the first Jagger-Richards composition to appear on the A-side of a single in Britain. As one critic described it, “What lifted ‘The Last Time’ out of the ordinary was the four-note phrase by Keith Richards that slithered through the lyric with a malign, unignorable persistence, like migraine rendered into sound.” The night of its release, the Stones played on the TV show Ready, Steady, Go! Frenzied fans stormed the stage. On March 18, “The Last Time” went to number one in the U.K. In the U.S. it reached number nine. In April, their third U.S. album, The Rolling Stones , Now!, went to number five. Richards and Jagger had perfected a formula and pinned an audience. “They had a terrific aim on the junior high mentality which pervaded rock from the start,” said Albert Goldman. “But the Stones took that kind of juvenile orientation and turned it around on its nasty side, particularly among the boys of that age group, with one finger up their nose and one up their ass wanking it. That seemed to me pretty much the center of gravity for the Stones.”

For years Jagger was credited in the media as the Stones’ main songwriter. It was little known that the early Stones originals were primarily Richards compositions. When he was at school Keith appeared to have a bad memory, but he discovered that he kept bits of songs in his head and could produce them at will. Occasionally he taped his riffs, but for the most part he just relied upon the tape recorder in his brain. Clearly Richards needed Jagger to pull these songs out of him. Sitting knee to knee in vans, planes, trains, dressing and hotel rooms, Jagger and Richards would play old blues numbers and then take off into their own compositions. Keith played his riffs slowly over and over again and made sounds that only Mick, who would translate them into lyrics and often speed up the beat, appeared to understand. It was, Keith said, like making love.