14. DEAD FLOWERS

1969—1970

All these guys running around in long hair talk about being wild and Rolling Stones. I don’t think someone abusing themselves on drugs necessarily determines how wild they are. It might determine how ignorant they are.

MERLE HAGGARD, from an interview with Ben Fong-Torres, 1990

“The day after Altamont they couldn’t get out of America quick enough,” said Ian Stewart. After a bracing breakfast of Old Charter whiskey and cocaine, Richards was the first to leave, but he found himself flying out of the fire and into the frying pan. News of Altamont had not yet reached England. At Heathrow Airport in London, Anita had told the assembled press that she was being threatened with deportation if Keith didn’t marry her. As soon as he emerged from customs, she held up Marlon and screamed, “Keith, they’re throwing me out of the country.” The reporters asked, “Keith! What are you gonna do about it?”

Weary from the tour, the horror, the flight, the sleepless nights, Richards replied, “It’s a drag that you are forced into marriage by bureaucracy. I refuse to get married because some bureaucrat says we must. Rather than do that, I would leave Britain and live abroad. But if I want to continue to live in England, and that’s the only way Anita can stay, we’ll get married. I have nothing against marriage—I’d just as soon be married as not. We’ll get it straightened out sooner or later, but first I’ve got to get some rest.” Later he confessed, “Anita and I in the sixties, we were never interested in marriage. It seemed an archaic and dumb thing to do just to have a child.” When they complained about the situation to Kenneth Anger, he suggested they have a pagan marriage ceremony. At first they were enthusiastic but Richards backed off when some of Anger’s black-magic preparations frightened him.

As the news of the disaster at Altamont hit the newspapers internationally, an avalanche of criticism came down on Keith and Mick. Their so-called friends in the rock business were quick to blame the Stones for either not consulting the right psychics or not reading the astrological charts correctly. The fact that it had been the California bands who had suggested the Angels work the show was played down. David Crosby, who was at Altamont with Stephen Stills and Graham Nash, took a typically damning stance. “I think the major mistake was taking what was essentially a party and turning it into an ego game and a star trip of the Rolling Stones, who are on a star trip and who qualify in my book as snobs,” he snorted. “I think they’re on a grotesque, negative ego trip, essentially, especially the two leaders.” The establishment viewed the violence as definitive proof of the Stones’ destructive, possibly satanic, powers.

In an interview with Ray Connolly at Cheyne Walk the day before a Stones Christmas concert in London, Keith answered the charges as directly as he could. If America was going to blame it on the Stones, he was going to blame America right back: “Do you want to just blame someone, or do you want to learn from it? I don’t really think anyone is to blame, in laying it on the Angels. Looking back, I don’t think it was a good idea to have the Hell’s Angels there. But we had them at the suggestion of the Grateful Dead, who’ve organized these shows before, and they thought they were the best people to organize the concert. The trouble is, it’s a problem for us either way. If you don’t have them come to work for you as stewards, they come anyway and cause trouble. In a way those concerts are a complete experiment in social order—everybody has to work out a completely new plan of how to get along. But at Altamont, people were just asking for it. They had those victims’ faces. Really, the difference between the open-air show we held here in Hyde Park and the one there is amazing. I think it illustrates the difference between the two countries. In Hyde Park everybody had a good time, and there was no trouble. You can put half a million young English kids together and they won’t start killing each other. That’s the difference.”

While the controversy raged, the Stones’ next album, Let It Bleed, which had been released on the day of the disastrous concert, began its rapid climb up the charts reaching number one in the U.K. and number three in the U.S. This extraordinary record, which opened with “Gimme Shelter” and closed with “You Can’t Always Get What You Want,” is considered by many to be the zenith of the Stones’ career. “They suddenly shifted from a head music of ideas about other people’s ideas to a genuine musical life flow,” wrote Albert Goldman. “The rolling, roiling moto perpetuo of ‘Sympathy’ showed that the Stones had a real musical body that answered to the rhythm of Mick Jagger’s body, shaking and soliciting from the stage. Now, in Let It Bleed, this movement toward musical and sensuous beauty reaches its culmination in a remarkable track that blazes a new trail for English rock.

“The beauty of the new record is not the expanded version of ‘You Can’t Always Get What You Want,’ featuring a sixty-voice boys’ choir, or the new country version of ‘Honky Tonk Women’—though those are good cuts for everyday consumption. The real Thanksgiving feast is offered on the first track, titled ‘Gimme Shelter.’ An obsessively lovely specimen of tribal rock, this richly textured chant is rainmaking music. It dissolves the hardness of the Stones and transforms them into spirit voices singing high above the mazey figures on the dancing ground. The music takes no course, assumes no shape, reaches no climax; it simply repeats over an endless drone until it has soaked its way through your soul.”

“‘Gimme Shelter’ is a song about fear,” read a review in Rolling Stone; “it probably serves better than anything written this year as a passageway straight into the next few years.”

By the time Keith returned to London, Anita was addicted to heroin. “After Marlon was born,” she explained, “it was a very heavy period and I suffered for about three months. There were so many creeps in the house. Then when Keith went on the American tour that was very hard for me because this is the time when the father should be with the child and I felt completely forgotten. So I just started taking drugs again, and then I smothered all my feelings with drugs. I spent most of my time with Marianne, just sitting together.” After he returned from Altamont, Keith also became, for the first time, a heroin addict, regularly purchasing pharmaceutical heroin from a man who stole it from chemists in the north of England.

Richards, who initially saw his addiction as a by-product of his profession, retreated into the toilet, the room in which he had always felt the safest since he had started playing the guitar.

RICHARDS: “It’s only the periods with nothing to do that got me into heroin. It was more of an adrenaline imbalance. You have to be an athlete out there, but when the tour stops, suddenly your body don’t know there ain’t a show the next night. The body is saying, ‘Where’s the adrenaline? What am I gonna do, leaping out in the street?’ It was a very hard readjustment. I was glad to be home but still hyper. And I found smack made it much easier for me to slow down very smoothly and gradually.”

“I felt I had to protect Keith,” Anita said. “He was flying so high in the music world. He couldn’t recognize a face or anything. He sat for hours and hours on the toilet. He used to play the guitar and write in the bathroom. And then when evening came he just got very nervous and didn’t know what to do with himself, basically, because he had this routine of being on stage. It was very hard for him.”

“I think it’s a drag,” Keith said, “when people thumping on the door go ‘Are you all right?’ ‘Yeah, I’m having a fucking crap!’ But people do it—I mean, if someone’s been in the john for hours and hours I’ll do it, and I know how annoying it is when I hear a voice coming out, ‘Yeah, I’m all right.’ ”

Marianne Faithfull had publicly cuckolded Mick during the American tour, leaving him for an old boyfriend of Anita’s, the Italian artist Mario Schifano. Dumbfounded, Jagger, who had become rock’s greatest sex symbol, summoned a backup girlfriend, the black actress Marsha Hunt, who starred in the smash hit musical Hair, to, as she saw it, “help him make the transition.”

MARSHA HUNT: “Mick was close to Keith Richards and Anita Pallenberg, who lived on the same road. After one visit to their house, I decided to keep my distance. I didn’t find their being into hard drugs cute or adventurous. Mick doted on Keith, and I didn’t voice an opinion but I avoided contact.”

Tony Sanchez, who was living at Cheyne Walk as Keith’s bodyguard and drug procurer for $250 per week plus room and board, saw how addiction was destroying Keith and Anita: Like all crafty junkies, Keith, who was paying for the drugs, began to hide his own private stash. Richards, who said he had never been a big fucker anyway, had not fucked Anita in months, and Tony often heard them fighting about it.

Ever since he had escaped the isolation of childhood, Keith had collaborated with Mick, Brian, or Anita. Now heroin became his collaborator. Keith and Anita had never had many close friends, but as Anita’s salon fell away they spent most of their time holed up at Cheyne Walk, with Tony and their drugs.

According to Dr. Joseph Gross, a New York specialist in, among other things, helping rock stars and other creative artists grapple with the tentacles of drug addiction, drugs can appear to boost creativity for a short time: “They may be used constructively and they may be used destructively, but it’s really hard to tease out a consistently clean line between them.... One would suppose that at first the heroin blotted out all interfering influences so he could be, you might say, ‘free to create.’ ” The womblike atmosphere at Cheyne Walk was also important in supporting both the addiction and the freedom to create. “One might see a real need for all these domestic supports so he could be a pure child musician,” explained Dr. Gross. “Musicians are like sheep. They must be literally guided or else they just sort of wander off a cliff. They need someone to take care of all the other business while they’re involved in doing their particular musical thing.”

Although he denies that heroin had any effect on his work, and claims that he could have written “Honky Tonk Women” or “Tumbling Dice” without heroin, Richards’s use of drugs is probably as significant to his actual creative work as it was to William Burroughs’s. The years 1970 and 1971, Keith’s honeymoon period with addiction, would be his peak as a songwriter. Even Jack Nitzsche, who had felt so uncomfortable when he’d visited Keith and Anita in 1969, agreed that Keith was still “putting reality into the Stones. And junk or no junk, it’s the only reality.”

While Richards reacted to the horrors of 1969 by withdrawing into the neutral zone of junk, Jagger began to re-create himself on a safer, more empowered plane. But as he took a firm hold on the reins of the Rolling Stones, Jagger lost his three closest friends to heroin. His relationship with Marianne, whom he had quickly won back from Schifano, fell apart again, as she too became a heroin addict. Many in the Stones’ entourage thought that his heart was broken by Marianne Faithfull and that that was why he never fell in love again without reservations. Whatever the psychological checks and balances, from 1970 on Jagger increasingly devoted himself to moving away from the satanic and hard-drug images and to attaining a power base in the worlds of glamour and influence.

As Richards commenced his long slog through “Dopesville,” Jagger, who had flown out of the ash pits of Altamont to Switzerland, where he deposited the $1.2 million in cash the tour had generated, turned his attention to financial matters. The Stones had come to the end of the tether with their record company, which had not only cut a side deal with Oldham and Easton in 1963 that gave them royalties due the band, but continued to nickel and dime the Stones despite their steady and increasing sales. In addition, by now they all realized just how grievously Allen Klein had misled them.

“There’s corruption in just about every business, but I’ve never seen it anything like the level of the record business,” noted the veteran Wall Street Journal reporter Fredric Dannen. “I’ve covered the coal business, insurance, investment banking, the chemical industry, and trucking; and although they all have their roguish elements, they’re nothing like the record business, which to my way of thinking is no business at all. I don’t know how to describe it except as some sort of cartel.”

Richards had become infuriated when he’d discovered that the money they had made from Decca had been invested in devices that aided American bombers in hitting targets in Vietnam.

RICHARDS: “How can you check up on the fucking record company when to get it together in the first place you have to be out on that stage every night? I’d rather the Mafia than Decca.”

They were determined to extricate themselves from both deals. In 1970 they decided to terminate their contracts with Decca and Klein, manage themselves, and form their own record company.

To oversee the complex transition and manage their financial affairs, Jagger hired Prince Rupert Ludwig Ferdinand zu Loewenstein-Wertheim-Freudenberg (a descendant of the Bavarian royal family whose title was a matter of debate since several of his predecessors had been mere counts). Described as a “podgy, camp, but affable, bright fellow with the lightest of accents, whose mother was rumored to have run a button factory,” Prince Rupert Loewenstein had “helped Jonathan Guinness set up the merchant bank Leopold Joseph.” By the time Jagger was introduced to him, Prince Rupert was grounded in Eurotrash aristocracy and cross-connected to what would become the international hip crowd of the 1970s. These were exactly the kind of people Keith and Anita most despised. However, Loewenstein clearly had two outstanding advantages over Klein: A deft financial manager, he was scrupulously honest; and he was able through his connections to construct for the Stones an international network of lawyers and accountants who would serve to protect both their money and them. As a result, not only would Keith Richards be able to continually elude the police of every country he entered, but between 1970 and 1990 he would move from the edge of bankruptcy to a net worth of approximately fifty million dollars.

Jagger arranged for the Stones’ records to be distributed in America by Atlantic Records, whose suave, jet-setting Ahmet Ertegun had a fine resume as a producer of blues and was well connected beyond the insular world of rock music. Like Loewenstein, Ertegun represented the new international chic that Jagger was trying to substitute for the Stones’ satanic image. “Control was what Ahmet and Prince Loewenstein had to offer the Stones,” noted George Trow in The New Yorker. “Both offered access to productive adult modes—financial and social —that could prolong a career built on non-adult principles.”

After ten years in the rock business, Keith didn’t trust anybody and was suspicious of the sophisticated, smooth international types. Trow, who spotted him at a party Ertegun gave for the band to celebrate signing the distribution deal, wrote that “Mick’s mate, the jaded weasel, wasn’t so eager to have his tail cut off, and socialized only with the other guests who still had one to wag: Keith Richards, the other essential Rolling Stone, left the party early. He was looking for his dog. ‘I have to find my dog,’ he said. ‘That’s my only friend at the party, man.’”

To run Rolling Stones Records, Jagger appointed Marshall Chess, a scion of Chicago’s Chess Records family. His interaction with Keith and Mick gave him an intimate view of them.

MARSHALL CHESS: “Mick is very smart, but to me Keith is the Rolling Stones. I always say that if the Stones finish tomorrow, Keith would still be Keith. He’ll always be the way he was; he’ll never change. He may have more money, more drugs, more drink, more whatever, but he’ll always be Keith and his favorite meal will be bacon and eggs with brown sauce; he is the constant factor.”

For the label’s logo they chose the famous lapping tongue, often incorrectly said to be based on Jagger’s. According to Richards, “It’s Kali’s tongue. Kali is the Hindu female goddess. Five arms, a row of heads around her, a saber in one hand, flames coming out the other, she stands there with her tongue out. But it’s gonna change. That symbol’s not going to stay as it is. Sometimes it will take up the whole label. Maybe slowly it will turn into a cock.”

On July 30, 1970, another new man on their team, the veteran British publicist Les Perrin, announced that the Stones had formally ended their relationship with Allen Klein and with Decca Records and its subsidiaries. However, in negotiations that were yet to be finalized, Jagger and Richards would lose to Klein the publishing rights to all their compositions from 1963 to 1969. Ironically, Richards had little to do with arrangements that were to have such an impact on him.

RICHARDS: “I’m only forced to become a businessman for short periods of time. Once a year I go through the little folder. This has come in, this has gone out, this is a projection of next year. And then I wonder why I bother to read it anyway, because it hasn’t made the slightest bit of difference to my day, or the next day. What’s important is that I keep on doing what I do, not how much money it’s making. Because all that matters really is that it generates enough money to keep going. That’s all that’s bothered any of us. Even so you can say, ‘You fucking liar, you’ve got three Rolls-Royces and huge houses all over the place,’ but I mean they’re like there, see. I might as well not have them—it wouldn’t matter that much to me. They’re there just because I’ve had surplus capital. It hasn’t affected whether I do what I do. As long as there’s enough bread to pay for guitar strings and food and a roof over the head, you can keep going and that’s all that’s important. I live on the road three or four months a year. I’d like to do more of it. And that’s probably the least luxurious way of living I can imagine. Even if the hotels are the best ones, hotel rooms are hotel rooms.

On looking into their accounts, Prince Rupert discovered that despite the fact that they had generated two hundred million dollars during their seven-year run, so much of the money had slipped through their hands that taxes would bankrupt them if they didn’t move out of England by April 1971, the start of the tax year. Consequently, in the midst of renegotiating their record contracts, launching a lawsuit against Klein for twenty-nine million dollars, putting together Rolling Stones Records, and recording their next album, Sticky Fingers , Keith had to contend with leaving his new Cheyne Walk house and Redlands and relocating to some foreign country where the people didn’t speak English or serve the English food—like shepherd’s pie—that was all he liked to eat.

The Sticky Fingers sessions inaugurated the new period in which the rest of the band would be forced to live on “Keith Richards time.” “He worked on his own emotional rhythm pattern,” said recording engineer Andy Johns, who never saw Keith stop to explain anything. “If Keith thought it was necessary to spend three hours working on a riff, he’d do it while everyone else picked their nose.”

The making of Sticky Fingers in the summer of 1970 marked a turning point in Richards’s career. With the exception of “Brown Sugar” and “I Got the Blues,” which were included on Sticky Fingers, Richards had by his own account now written all his favorite Stones songs. A list of his top-ten favorite Stones songs, compiled in 1990, read: “Jumpin’ Jack Flash,” “Street Fighting Man,” “Satisfaction,” “Honky Tonk Women,” “Gimme Shelter,” “Sympathy for the Devil,” “Midnight Rambler,” ‟Brown Sugar,” “Ruby Tuesday,” “I Got the Blues.”

Keith, who had been so angered by Brian’s habit of missing sessions or showing up too stoned to perform, started to do the same thing. By the time the Stones came to record “Moonlight Mile” (which was composed by Jagger and Taylor), Keith was so out of it that he didn’t play on the track at all. Also, he started importing session musicians who would increasingly shape the band’s sound. At first Keith’s position in the band was bolstered by the influence and playing of the like-minded musicians he imported. Gram Parsons made major contributions to “Wild Horses,” “Country Honk,” “Dead Flowers,” “Far Away Eyes,” and “Sweet Virginia.” Parsons and many others who would travel on Keith’s road over the next two decades were replicas of Jones. A second character in the mold was a twenty-seven-year-old Texan sax player Bobby Keys, who was born on the same day and in the same year as Keith, and had played with Buddy Holly. “A lot of people overlooked the fact that it wasn’t just Mick Taylor joining the band that changed our sound in ‘69—that was the whole period where the horns joined too,” Richards pointed out. “Both the horns and Mick Taylor made their debut on Let It Bleed on ‘Live with Me’ at the time.” A roly-poly, pasty-faced, rollicking lad whose brand of Southern humor contained a racist vein, Keys became Richards’s new drug sidekick as well as brilliantly complementing Keith’s guitar playing on numerous Stones classics, like “Brown Sugar.” Richards, he said, always reminded him of Buddy Holly.

Keys’s entrance into the Stones, something Jagger was always dubious about, served to further enhance Richards’s leadership. Keith, who was always trying to connect back to their roots, was fascinated by Bobby’s background.

RICHARDS: “It’s a gas not to be so insulated and play with some more people, especially people like Bobby, man, who on top of being born at the same time of day and the same everything as me has been playing on the road since ‘56, ’57.”

Watts and Wyman—who rarely took drugs, although Watts was at times a heavy drinker, and thus were dubbed the straightest rhythm section in rock and roll—remained passively in the background, going about their tasks with extraordinary efficiency, considering the extreme aggravation caused them by the new Keith. Mick Taylor, who never bonded with anybody in the band although he and Keith enjoyed a mutual admiration as players, insulated himself.

RICHARDS: “He was very reluctant to take any direction. I don’t mean from the band, because we don’t tell anyone what to play, but from the production end of it. Jimmy Miller used to go through reams of frustration, saying, ‘Tell the guy not to play there!’ Meanwhile, Mick is over there and he’s just going to do what he’s going to do. And so he did it.”

Jagger was most affected. He was particularly jealous of Keith’s relationship with Gram as they began to work on “Wild Horses” together. Mick observed that Gram flattered Keith a lot and doubted Gram’s motives, believing that Parsons was just trying to pick up some glimmer from them. “Mick’s very, very possessive,” Keith said. “His attitude was ‘You can’t have him.’ ”

ANITA PALLENBERG: “To a certain extent Mick will bitch about whoever is in Keith’s life. He always put down all of Keith’s friends. But Mick didn’t realize that because he is the one who actually writes the tunes Keith needs his own sources. Gram had an enormous influence on Keith, that’s for sure. Keith used to listen to Vivaldi and classical music for inspiration and Gram was definitely a source of inspiration.”

Despite what might have appeared to be interruptions, the Glimmer Twins operated as a unit. According to Mick Taylor, they continued to be the creative force within the band and they made all the decisions for the Stones.

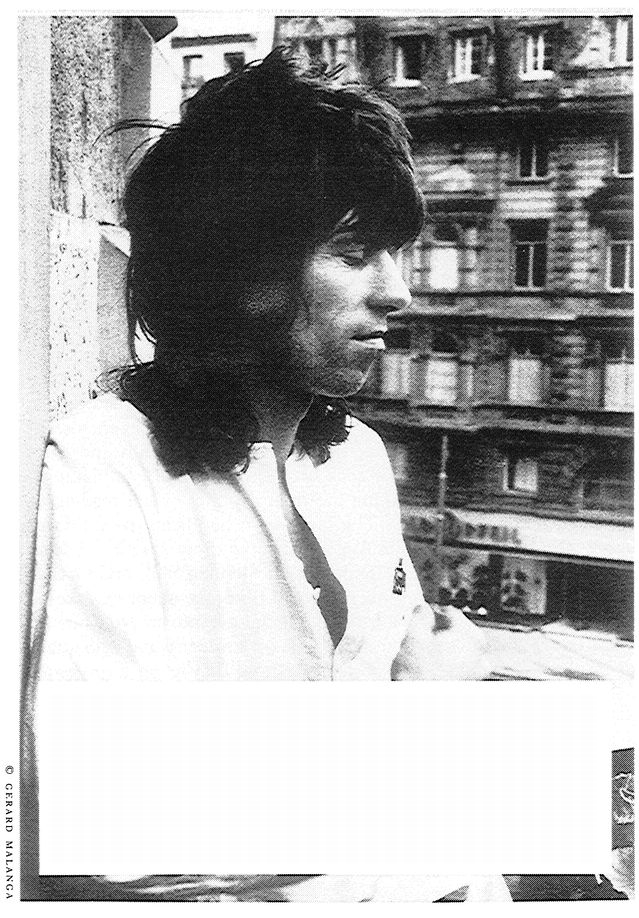

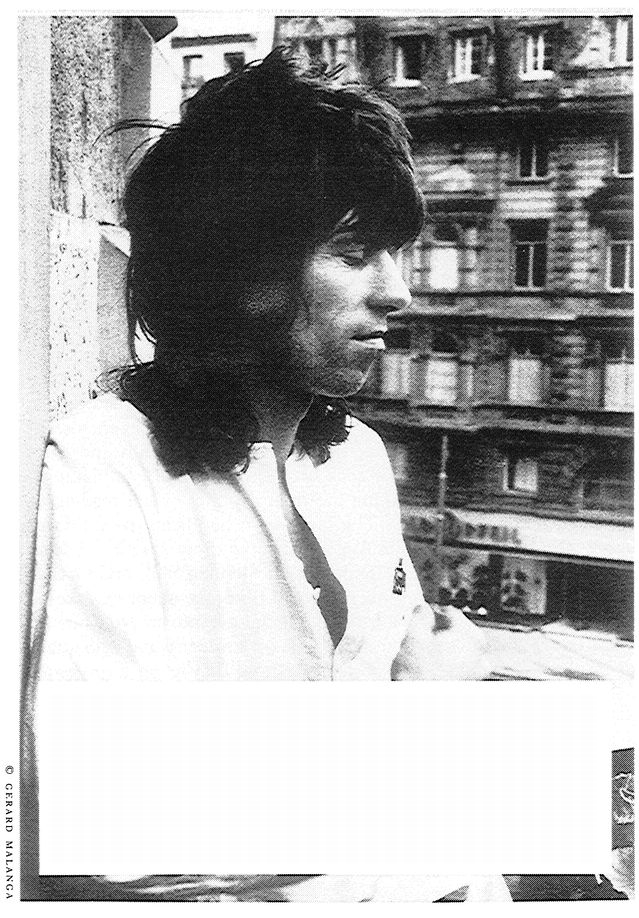

From September to October 1970, the Stones toured Europe with Bobby Keys; Jim Price, another horn player; and Nicky Hopkins on keyboards. To their fans, everything the Stones did appeared to be perfect. They particularly liked Keith’s new look, which reeked of contempt for all the sartorial symbols of the status quo, from the glittering, sequined blouses of a female fashion model, which he borrowed from Anita, to the carapace of shoulder-length black hair that set off his wolfish skull and ghoulish face painted the colors of Nosferatu and emphasized his nodding head and hooded eyes. Despite Mick’s desire to pull back from the edge of the devil’s pit, once the music started a fervor gripped the crowd. Riots, arson, arrests—entropy—accompanied every show. “They were totally freaked out,” recalled John Dunbar, who operated the lights. “They’d see Mick and they were going, ‘Mick! Mick!’ Guys weeping—it was like the fucking holy virgin. I was on stage with them. I was watching horrible shit, watching all of these people.”

Rather than travel with the band, Keith traveled with his own junkie’s entourage: Anita, Marlon, a nanny, Bobby Keys. Every time they crossed an international border they were bound to be searched. Scoring heroin in the brief, highly pressured time they had in each city was nigh impossible given their flamboyant appearance and international fame. Being a junkie is not just a way of life, it’s a job, and Richards, who believed that a professional always specialized, took a hands-on approach to the problem. First, he acquired several James Bond-type devices in which to carry his stash. There was, for example, the fountain pen that operated normally and would have drawn no suspicion unless dismantled. It could carry two grams of white powder. Then there was the shaving cream container. Keith took great pride in outsmarting customs officials because it emphasized how bad they were at their jobs and how good he was at his. Should any drugs be discovered, as they occasionally were, the increasingly tight safety net that contained the Stones would take care of the situation. So much money was at stake that Keith could demand and get what he needed to perform. It was taken for granted now that without him there would be no show. In some cases promoters found themselves saddled with the dicey task of locating the necessary narcotics at the last minute, and audiences were kept waiting for an hour or two while they scrambled around to find enough heroin or cocaine for a night’s show, but Richards never missed a gig, and for the most part he still managed to lead the band on stage night after night. As the British writer Jon Savage has pointed out, “One of the problems of heroin use is that, although the drug offers insulation from the stresses of everyday life, it does so by effectively embalming the user’s body and emotions.” For the first time on tour, instead of being the social fulcrum of the band, Keith became antisocial and was forever falling asleep or spending hours on end in the bathroom. Ian Stewart, who regarded Richards’s disintegration as “a bloody tragedy,” reflected on how ironic it was that Keith, who had always been the one most angered by Brian’s druginduced incapacity, had somehow turned into Jones.

The establishment of Keith Richards as a man not so much of wealth and taste as death and waste was completed by the release of the two works that perfectly completed the Stones’ sixties oeuvre, the live album of the 1969 U.S. tour, Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out!, that September and the tour film Gimme Shelter in December, for which the ad read, “The music that thrilled the world ... and the killing that stunned it!”

“I’m beginning to think Ya-Ya’s just might be the best album they ever made,” wrote the American rock critic Lester Bangs in Rolling Stone. “ ‘Little Queenie’ as done here is all-time classic Stones. Just strutting along leering and shuffling, the song has all the loose, lipsmacking glee its lyrics ever implied. This kind of gutty, almost offhand, seemingly effortless funk is where the Stones have traditionally left all competitors in the dust, and here they outdo themselves. I even think that this is one of those rare instances (most of the others are on their first album) where they cut Chuck Berry with one of his own songs.

“ ‘Honky Tonk Women’ is just a joy, but ‘Street Fighting Man’ takes the show out on a level of stratospheric intensity that simply rises above the rest of the album and sums it all up. Keith’s work here is a special delight, great surging riffs reminiscent of some of the best lines on the first Moby Grape album, or the golden lead on Stevie Wonder’s ‘I Was Made to Love Her.’ I don’t think there is a song on Ya-Ya’s where the Stones didn’t exceed their original studio jobs. And this one leaps perhaps farthest ahead of all.”

In Gimme Shelter, it was Richards who came across as what he really was: the quintessential, bad-ass, immovable Rolling Stone. This was particularly striking in the footage of Altamont when, as Jagger realized he was losing control and fear crept into his voice, Richards spoke his mind. “As a work of art it was exquisite, the culmination of the Stones’ oeuvre, not to mention a great movie script,” wrote Robert Christgau. “Keith Richards, the stud to Jagger’s sybarite, acknowledged its aptness in his own rough way: ‘Altamont, it could only happen to the Stones, man. Let’s face it. It wouldn’t happen to the Bee Gees and it wouldn’t happen to Crosby, Stills and Nash.’”