21. ALL ABOUT YOU

1979

Keith has the constitution of concrete. He’s like a cliff. The sea comes and washes up against it and it stands. But so many people who were around him would just collapse. Keith is the sort of person who can stay awake for three days without substances and all of a sudden fall alseep in midsentence sitting up and not moving for a few hours. He would just be up and up and up and up and up and all of a sudden it would be like a light switch, bing! But in certain strange positions. Then you would walk around him.

RICHARD LLOYD, from an interview with Victor Bockris, 1992

In December 1978, Keith, Anita, and Marlon flew the Concorde to London to spend Christmas and the New Year there as well as to see Keith’s mother and daughter. Anita’s appearance would have shocked anyone who had not seen her in a year. Bloated, with hairy legs, blotched green-hued skin, missing or rotting teeth, and unkempt hair, she drifted through time making half-hearted efforts to fulfill such motherly functions as pulling a meal together. When Marlon asked for dinner, he was often presented a plate of ice cream. But Keith still spoke reverentially about her. “She’s everything, man,” he told an acquaintance. “It all comes from her, the Rolling Stones.” In truth, though, instead of being the great Rolling Stones catalyst she once was, she now had an effect on Keith that was altogether negative.

Keith’s focus during the holidays was on collecting tunes for the next album. The London music scene was very hot. Punk was self-destructing in a blaze of publicity over the breakup of the Sex Pistols and Sid Vicious’s alleged drug-crazed murder of his girlfriend, but there was still a lot of energy pumping up from the underground. Groups such as Siouxsie and the Banshees, the Buzzcocks, and the Clash were hotter than ever. On top of that, there was a virtual heroin epidemic sweeping the scene, as cheap Iranian heroin poured into town. When the seventies reached their apotheosis around the world, revelers found themselves in the forefront. Instead of picking up on the action, Keith holed up in an opulent suite at the Ritz Hotel in Piccadilly, overlooking Green Park. There, he and Anita kicked back behind a wall of cocaine, marijuana, booze, and the music that still played continuously on tapes and in his mind. He was immersing himself in what would become Emotional Rescue.

Keith had discovered how to use the press as a line of communication to the rest of the band in a 1971 interview in Rolling Stone, and he now took the opportunity to mend some bridges and let everybody in England know he was alive and well.

“I’ve done my best over the years to sort of change the course of things here and there,” he once told Lisa Robinson. “Rock and roll and popular music won’t exist if it’s boring. The only thing that keeps it going is that it’s popular and people like it. I know nothing about the state of the industry. I think what helped make the music business so complacent in the last few years was that they knew that they could shlep out an Eagles album and it would sell so much. Circumstances changed and suddenly they’re running around like ‘Oh, my God, they’re going to send me back to the A&P and I’m going to be the manager of a supermarket.’ I like nothing better than to watch all these record company executives shit themselves.”

He opened a new campaign to keep the Stones together by summoning to his suite the rock critic Chris Welch, who had written extensively about the Stones for Melody Maker in the sixties, for a major interview. “Keith, who now kept life at bay with hearty draughts of vodka, was an extraordinarily charming man, possessing infinite patience,” wrote Welch. “While his speech and thoughts were sometimes held in check by the flow of soporifics and stimulants holding their own press conference inside his head, his acerbic wit and hard-bitten worldly wisdom remained intact.” While talking about the flourishing London music scene, Keith fended off the standing criticism that he dismissed punk, new wave, and other rock trends.

RICHARDS: “I think punk rock was great theater, and it wasn’t all crap. The music was all incidental, like background music. You just had to see it. It’s a little too image-conscious from my point. It’s like in the 1960s, ‘We’ll put this band in these clothes, we’ll dye his hair.’ As long as the band’s good, I don’t care what color they dye their hair. But anything other than California rock, anything but complacency, yeah, sure.

“I’m probably a little out of touch with the music scene here, but most of the stuff that’s happened has lost touch with itself anyway. It’s back to fads. One minute it’s the Bay City Rollers, then it’s punk rock, then it’s power pop or new wave, then it’s finished. People are back to sticking labels on things. Elvis Costello. I’ve ’eard his stuff. I’d sooner see him live, that’s all I care about. I don’t care about album production. I like Ian Dury, he’s down to the bone. As long as there’s something happening here, that’s all that really matters. Where they went wrong with the punk thing was they were trying to make four-track records on thirty-two-track. We were trying to do the same thing in a way. We tried to make 1964 sound like 1956, which wasn’t possible either. But we did end up with something that was our own.

Throughout the interview Anita chided him with sarcastic remarks and called him a baam claat man (a baam claat was a cloth used in Jamaica to mop up the blood of whipped slaves). Just as Linda Keith had ended up deploring Richards’s musical direction, Anita attacked his refusal to develop a solo career. To the interviewer she insisted that he had future plans to get out a solo album. Keith demurred, saying he didn’t give a shit.

RICHARDS: “I don’t have time to think about doing stuff on my own. I’d just be cutting myself off from the Stones in one way, and that’s not going to help anybody. I’m not interested. The basic thing about the Stones is that there is an understanding that there are five guys in the band, and there might be a few others involved in the making of a record, but what comes out of the speakers is basically one sound. It’s like a watch—there might be fifteen little jewels in there, and all kinds of things ticking around, but if it don’t make the hands go round it’s no bloody good.” In fact, he had released a poorly received single (“Run Rudolph Run”/“The Harder They Come”) in the States in December’78, and there were persistent rumors in the press throughout 1979 that Rolling Stones Records was going to put out a Keith Richards solo album based on the Toronto tapes called Bad Luck. The question was whether Keith would work without the Stones. He would duck the issue for the next eight years.

“For what I do and what the rest of the band does, I don’t think I could do it any better elsewhere, in a different setup,” he told Welch. “Sometimes I might do the odd song alone, and that’s the way we’ve always worked. Mick might say, ‘Your rough tape has got the best feel, why don’t you do that one?’ But we still work closely on songs.”

In 1979 Keith’s songwriting output was prodigious. Apart from the songs that later appeared on Emotional Rescue, particularly the outstanding “All About You,” on which he sang the lead vocal, and “Little T & A,” on which he also sang lead and which would wind up on Tattoo You, he wrote a number of exceptional unreleased songs that year, such as “Let’s Go Steady” and “We Had It All.”

Richards’s biggest headache in these choirboy days was the possibility of a reopening of the Toronto case. In November 1978 his worst fears had surfaced. The crown prosecutor had won an extension to appeal his sentence, and now Keith was back to attributing the whole brouhaha to political squabbles.

RICHARDS: “It’s Canada vs. the Rolling Stones. I mean, I didn’t screw Margaret Trudeau. Ah ha! But in that case—who did? Who ripped the flimsy bathrobe aside? I end up feeling like I have to pay for the rape of Canada. But I didn’t have nothin’ to do with it.”

Keith was still reveling in the international success of Some Girls when he flew into Nassau in the Bahamas on January 20, 1979, to begin work on the sessions for the album Emotional Rescue. His head was full of ideas and his pockets jammed with cassettes of outtakes and rehearsals he had collected in England. But Keith’s ideas met with opposition from the band.

RICHARDS: “You write a song, you have a certain feel, it’s supposed to go this way, or you feel it’s supposed to be very minimal lyrics, just sort of a chant, and here Jagger comes zoomin’ in to the studio with a goddamn opera! You can’t always click exactly right. Those things happen all the time. You say, ‘I just can’t see it any other way. I’m sorry.’ And you go through all of that. When you’re writing songs twenty years with a guy, you go through loads of these sorts of things. It’s part of the process.”

Richards was so determined to get the recordings just right that he would eventually delay the release of the album until he could be sure that the track “All About You” hadn’t been subconsciously taken from another artist. And yet he was critical of Jagger’s similar hands-on approach. Keith thought Mick was too involved with the businesspeople.

RICHARDS: “One of my points was that he had his hands on everything. Mick, nobody can do everything. And you’re also wasting the big gun. I remember with Allen Klein renegotiating our record contract, we sat there in front of this board of directors and did not say a word. That’s one of the greatest weapons the Stones have, the fear we inspire. If you’re dealing with these people all the time, they get to know you too well. One of the Stones’ greatest strengths in doing business was that we never said a word.”

MICK JAGGER: “I read these things always: ‘Mick’s the calculating one; Keith’s passionate.’ But, I mean, I’m really passionate about getting things right. And if I’m not passionate about the details, some slovenly person that’s employed in this organization will just let everything go.”

“There was this awful inability to lead a separate existence,” observed the British rock critic Michael Watts. “They were tied to each other creatively. They may have liked each other, but they really didn’t want to be married and I don’t think they ever really talked about the horror of it. One can imagine what a horror it must have been. It wasn’t even like being brothers—they depended on each other for their livelihood. This operated far more in their case than it did with Lennon and McCartney, who were separate individuals. They had to work out some kind of rapprochement together. As they went into the 1980s I think that was the perception that a lot of people picked up.” Punch magazine humorously likened the pair to other iconic, homoerotic duos, placing them in league with Gilbert and George, and Laurel and Hardy.

“It’s a true friendship when you can bash somebody over the head and not be told, ‘You’re not my friend anymore,’ ” said Keith. “You put up with each other’s bitching.... He’s my wife. And he’ll say the same thing about me.”

“Mick and Keith are going to have to face each other eventually,” said Anita. “They should get married. The mayor of New York should marry them.” Earl McGrath, who had replaced Marshall Chess as president of Rolling Stones Records, was of the opinion that “Keith didn’t care about anything except Mick Jagger.”

Keith particularly resented Jagger’s refusal to tour in 1979, not least because it left him not knowing what to do. He also continued to resent Jerry Hall, knowing she would keep dragging Mick into the celebritystudded disco world of Studio 54, which Keith saw as “a room full of faggots in boxing shorts waving champagne bottles in your face.” The conflict that had made for creative tension had become a power struggle that would undermine their work throughout the eighties.

Keith had found a new drug partner in the comedian John Belushi, and as soon as he hit New York from Nassau in late February, he was spending nights staying up with John. Keith was a student of comedy, John was a champion of blues, and both were dedicated users. Keith sensed the same “I won’t make it to thirty” quality in John he had in Brian Jones. Others saw Belushi as another victim of the Keith Richards life-style. When James Brown played Studio 54, Keith showed up in his dressing room with John, who had featured Brown in his film The Blues Brothers. They “sat around talking to me,” Brown recalled, “but John was well out of it that night, and I remember thinking I wish I could be with him more and talk to him and help him straighten out.”

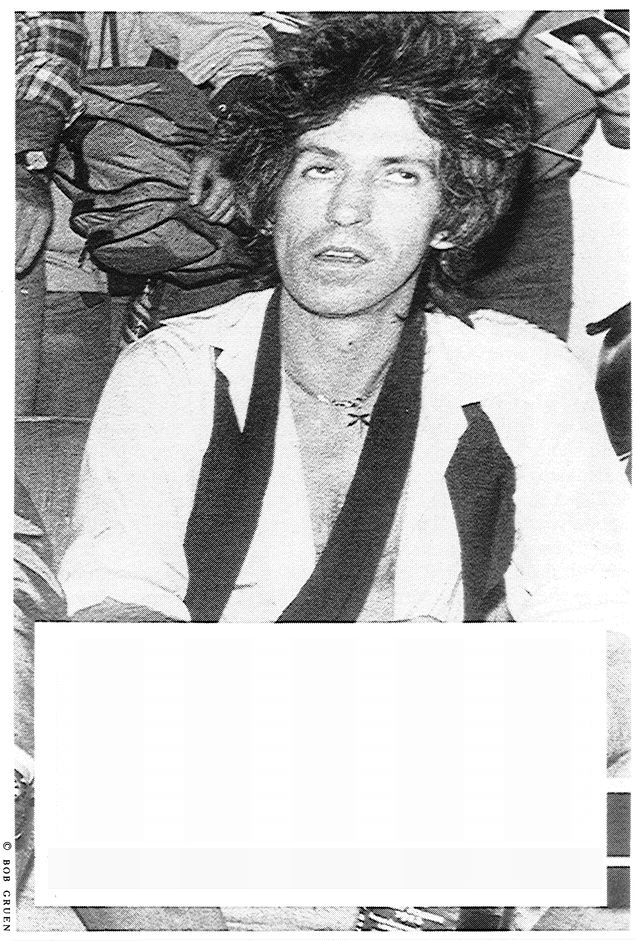

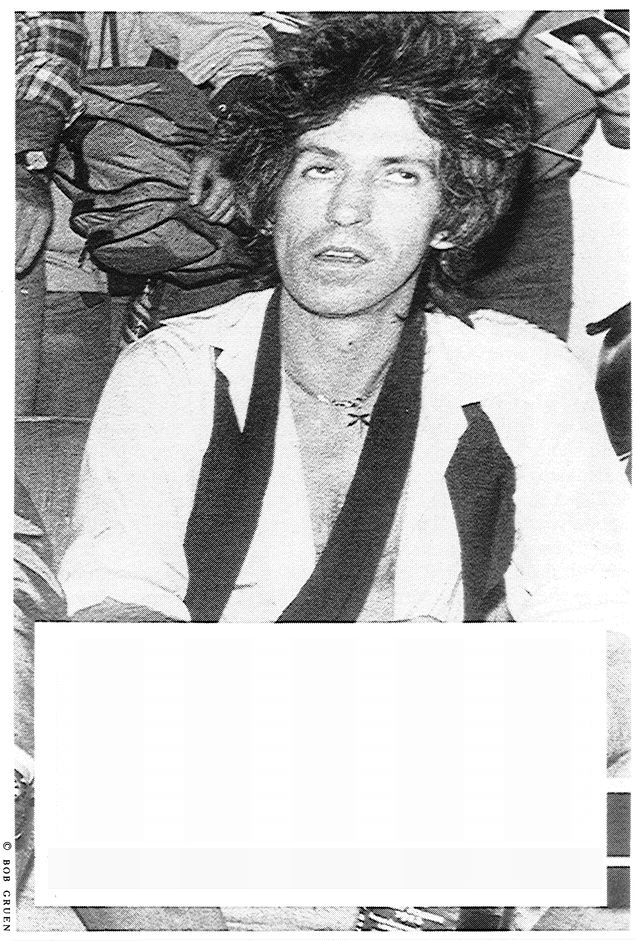

Rolling Stones Records announced plans to release a Keith Richards solo single, “Bad Luck,” in April, followed by an album of the same title but the disc was never released. In March Jonathan Cott saw Keith at Peter Tosh’s show at the Bottom Line. “He looked as if he had just been taken down from the cross,” Cott wrote. “He was incapable of getting around the room by himself and had to be virtually carried out of the club.” Richards’s survival instinct told him to get busy or die.

Richards did the previously unthinkable when he decided to tour in 1979 without the Rolling Stones. Ron Wood, who had less invested in his identity as a Stone, was putting together a band, the New Barbarians, with Ziggy Modeliste of the Meters on drums, the seminal jazz musician Stanley Clarke on bass, Ian McLagan of the Faces on keyboards, and Keith’s old buddy Bobby Keys on sax, to do a brief spring tour in support of Wood’s latest solo album, Gimme Some Neck.

RON WOOD: “It was easy to get Keith to back me up because he wasn’t doing anything else. ‘Hey, Keith.’ I rang him up. ‘You gonna sit on your ass for another few months or what?’ Keith just said, ”If you’re touring, I’m in on it.’ ”

Keith had been in a dilemma about going into Canada to play the April 1979 concerts for the blind since the Canadian authorities could serve him with a subpoena on the appeal of his sentence and confiscate his passport. However, while he was rehearsing with the New Barbarians, his lawyer worked out an arrangement so that he could go into Canada and play the concerts, if he agreed to appear in court the following day to acknowledge the appeal.

On April 22, backed up by the New Barbarians and, in a surprise appearance, the Rolling Stones, Richards played two shows for the blind at the five-thousand-seat Oshawa Hall outside Toronto. Backstage before the first show Keith was bubbling with excitement. “It’ll be a good show!” he promised Chet Flippo. “We’ll just do ‘Some Girls’ and see how it works.”

They were introduced by an ebullient John Belushi, who screamed, “I’m a sleazy actor on a late-night TV show, but I’m going to present some real musicians!” The high point of the show came when Keith and Mick sang “Prodigal Son” together on stools in front of microphones with an acoustic guitar, just as they had done when they started out together in a pub in Devon in 1961. The show raised fifty thousand dollars for the Canadian Institute for the Blind. Though still prodigal, the sinner had received full public absolution.

From April 26 through May 21, Richards went on the New Barbarians’ tour of the States, playing from Washington and New York to L.A. As they traveled across the country, Blondie’s “Heart of Glass” was topping the American charts, Bob Marley had picked up his biggest listening audience ever, and Elvis Costello was taking America’s forward-looking youth by storm. Ron Wood’s all-star band didn’t measure up to the standards set by these innovative artists. “We hit about fifteen U.S. cities in a month,” said Wood. “Unfortunately, there were all these fans yelling, ‘Mick! Rod!’ That was a bit of a blow to the ego. In fact, when we did Milwaukee, the kids literally tore up the place when no surprise guests came on. And we got slapped with a lawsuit.” But the critics, ranging from the acerbic Lester Bangs to The New York Times’s Robert Palmer and New Musical Express’s Charles Shaar Murray, were impressed with Richards’s stage presence, newfound energy, and apparent good health. There was, noticed one witness, “a new willful, jaunty bounce to his gait and an ease to his manner in general.” By some miracle, it was noted, his teeth had grown back!

For Keith it was a double pleasure all down the line. The Toronto problem was off his back for now. Instead of being in jail, he was off in his favorite place—on the road with a bunch of, in his opinion, “great musicians.” Despite drinking two fifths of vodka a night on stage, he had no trouble coming up after playing at his characteristic ankle level.

His visibility as an artist, not a junkie, had never been higher. His image was rehabilitated to the point where it was acceptable but still rough enough to be impressive. Keithmania prevailed. Bill German, editor of the Rolling Stones newsletter, Beggars Banquet, described the show at Madison Square Garden: “The handful of songs in which Keith had lead vocals had the crowd on their feet. Getting ‘a little variety,’ Woody played sax as Keith sang the old Sam Cooke song ‘Let’s Go Steady.’ Keith took up the piano for ‘Apartment No. 9,’ a sweet ballad taken from his upcoming LP. Keith also sang ‘Worried Life Blues,’ a song the Stones did at the El Mocambo. Keith of course did ‘Sure the One You Need,’ in which he had to quickly ad-lib for forgotten lyrics in the third verse. If you wanted to see 20,000 people go bananas all at once you should have been there as Keith sang ‘our rendition’ of ‘Before They Make Me Run.’ ”

“Behind Wood, nearly at the epicenter of the stage, the renewed man who has always played with the Rolling Stones is writhing in the music, backwards, forwards, almost falling to his knees as if it were his blood and not paint spilled on the stage, striking at his guitar in small, startled circular gestures as if it were too dangerous to really touch and, at the same time, as if it were irresistible—sweet pain—and showing (and showing off) that, the Rolling Stones aside, he’ll take his rock and roll where he gets it,” wrote Robert Duncan in Hit Parader. “Woody skitters back to the mike stand, which holds two mikes, and Keith writhes up next to him, directly on cue, as Zig Modeliste jams the band into overdrive and Ron and Keith and, off to the other side of the stage, Ian McLagan repeat chorus, repeat chorus, repeat chorus. Crash: ‘Sweet little rock ’n’ roller/Sweet little rock ’n’ roller.’ ”

Charles Shaar Murray saw the Dallas show and wrote: “Richards was goofing off more than any other big-time guitar player. Even when they laid down a ‘Jumpin’ Jack Flash’ encore sharp enough to perform open-heart surgery with, he still slid up to a climactic chord and missed it by a good three frets. He did everything but drop his pick, and stared down the audience as if daring someone to make something of it.”

The tour gave Keith his first taste of working outside the Stones. “The thing about being in the Stones—and baby, when you’re in the Stones, you’re in the Stones—you don’t get that much chance to go out on the road and play with other people, as a part of another band, just to keep your hand in,” he told Lisa Robinson. “It was a delicate situation, not to come on too strong. I was there to back Woody up and that’s what I tried to do. If you come on upstaging everybody, then there’s no bloody point in being there, because you might as well go out on the road on your own.”

Behind the scenes, however, the band had problems. In an unrealistic attempt to keep up his image as a Rolling Stone, Wood and his manager set up a tour that couldn’t make any money. Despite selling out their sixteen concerts (largely, some griped, on the strength of the hinted-at appearances of Jagger and Bob Dylan), the luxurious private jet, the fleet of limousines, and first-class hotels ate up the profits. Furthermore, although Wood’s album came out during the tour, it did not sell particularly well, and Keith’s much-heralded solo album, Bad Luck, was canceled. Consequently, imagined profits turned into a mirage, which particularly annoyed Richards, who was in need of money due to his enormous legal bills for Toronto. Lil, who accompanied Keith throughout the tour, said that it was different from a Rolling Stones tour in every conceivable way. “Of course he enjoyed it,” she said. “But there was also a lot of bullshit going on.”

Offstage, in the luxurious cocoon of limousines and first-class hotels, Richards showed signs of being lost. Witness after witness reported scenes of Keith, bottle in hand, spliff in the other, his puffy, lined face and graying hair showing age far beyond his years, staggering from hotel room to hotel room, barefoot and bare-chested, while a tape of the night’s performance roared out of his cassette player. “Do anything you want to do,” Keith told one visitor in his Dallas hotel room after a show, “just don’t touch me.” According to another witness, “He looked around as if he’d only just realized where he was and passed out, schlumpfed in a corner, cheeks drawn, mouth open, eyes shut, while a bunch of people he hardly knew rang room service on his tab, smoked his dope, and made free with his room.” His relationship with Woody, whom he now referred to as Squirt, was strained, as Keith’s buddy and biggest fan edged closer to becoming a casualty of the drug life-style.

On May 21 the New Barbarians finished the monthlong tour at the L.A. Forum. For a treat, in the town that seemed to be his nemesis, Keith bought some Persian Brown heroin from Cathy Smith, who would later be involved in John Belushi’s death. “I was reliving a second rock and roll childhood,” he said. “I could have gone back. Easy. It could have gone either way for me, life or death.”

“I have grimly determined to change my life and abstain from any drug use” was the opening line of a statement by Richards that was read by his lawyer in front of a panel of judges in a Toronto court on June 27. “I can truthfully say that the prospect of ever using drugs again in the future is totally alien to my thinking. My experience has also had an important effect not only on my happiness, but on the happiness at home in which my young son is brought up.”

On the basis of this statement and a positive report from the Turning Point program, the panel drew the conclusion that Richards had overcome his heroin addiction once and for all. In October it handed down a decision refusing to reopen the case. For the first time in nine years, Richards was totally free from the threat of incarceration. His ability to live beyond the law enhanced his legend and kept him in the world of make-believe. The same year Chuck Berry was sentenced to four months in prison for a minor case of tax evasion. He was one of many black R&B stars to suffer jail terms. Keith’s mojo was still working.

The extent to which Richards was protected was emphasized by two things that happened while the court was considering the appeal. Tony Sanchez published Up and Down with the Rolling Stones, a lurid account of his career as Keith’s drug procurer, which was serialized in the New York Post and syndicated across America. Sanchez portrayed Keith as a callous drug abuser, verging on evil, and Anita as a drug-crazed beauty turned hag. “She had been prey to the gross enlargement of conventional insecurities,” wrote one reviewer. Sanchez’s book was a grueling testament to the ten years of heroin addiction that had led to these tragic images.

RICHARDS: “I couldn’t plow through it all because my eyes were watering from laughter. But the basic laying out of the story—‘He did this, he did that’—is true. Tony didn’t really write it. He had some hack from Fleet Street write it; obviously, Tony can hardly write his own name. He was a great guy. I always considered him a friend of mine. I mean, not anymore. But I understand his position: He got into dope, his girlfriend OD’d, he went on the skids and ... it’s all this shit. As far as that book’s concerned, as far as, like, a particular episode, just the bare facts—yeah, they all happened.”

It was, wrote one critic, “the most nightmarish book on rock yet written. Mr. ‘Elegantly Wasted’ emerges as a self-centered skinflint, paranoid, the sort of man who toys with the idea of using his child as a smack courier. This desperate kiss and tell is a portrait of malevolence and imbecility.”

On July 20, just as the Sanchez book hit the newspapers, a seventeen-year-old boy named Scott Cantrell blew the back of his head off in Richards’s house, Frog Hollow, in South Salem, New York.

According to shocking press reports, Cantrell had killed himself in Keith and Anita’s bed with one of Keith’s stolen guns. The fact that Richards was living in his Paris flat with Lilly making Emotional Rescue notwithstanding, the negative publicity seared him like a lineup spotlight, bringing with it all the old charges about the Rolling Stones’ relationship with Satan, drugs, and death. Anita, who appeared in photographs and nightclubs around New York looking bloated and deranged, did little to quell rumors that she was involved with dispensing drugs to teenage boys and sex orgies, although she denies having sex with Cantrell. According to Anita, Keith called from Paris and was upset about the incident, but not because of the death. “He didn’t say anything about the guy, he just got annoyed with my negligence, being so sloppy and flopped out. He just said, ‘Oh, you managed to lose a piece, didn’t you?’ I thought that was very hard, because it was not a life, just the gun that had gone with the police he was concerned about.” Anita knew that this was the last straw, and that their commonlaw marriage, if not their fifteen-year relationship, was over. “That boy of seventeen who shot himself in my house really ended it for us,” she said. “And although we occasionally saw each other for the sake of the children, it was the end of our personal relationship.”

In and out of the court and the glare of the public eye for the rest of the year, Anita was finally cleared of any involvement in Cantrell’s death, pleaded guilty to possession of a stolen gun, was fined one thousand dollars, and was given a conditional discharge.

ANITA PALLENBERG: “For a while it was a nightmare. The lawyers told us we were no good for each other because of the drugs. They said we were a bad influence on each other. I always had my boyfriends on the side. It was loneliness. I didn’t think anything bad. I used to introduce them to him. He met them all. But I think the relationship was good. It wasn’t like Bianca and Mick or Angie and David [Bowie]. It was nothing like that with Keith. He’s a very understanding, a very human person and he appreciates home and he’s a really rewarding person.”

Anita was more dangerous than ever—fat, strung out, and horrified by what her life had become. She lived in hotels, apartments, and houses in New York or Long Island paid for by Keith, watched over day and night by surly “friends of Keith’s,” large, silent English bodyguards and roadies whose conversations were at times so psychotic she was thankful for their silence. She cried to friends that she really wanted just to get back together with Keith and have a family, but when they recommended that she lose weight, see a hairdresser, and go to the gym, she scoffed that she had already been a top model. To his entourage she seemed a pathetic wreck, but Anita knew Keith was still frightened of her and attracted to her. Some time after Cantrell’s suicide they met in a New York hotel room. “I was really overweight,” Anita remembered, “and I really didn’t think he liked me, but I guess he loved me because he still wanted to make love to me. But I didn’t feel worth it,” she recalled, “for him. I said, ‘You bring out the worst in me.’ ” For Keith, Anita still had the lure of the divine mother. She inspired one of the best songs on which he sang the lead vocal, the elegiacial “All About You,” which would come out on Emotional Rescue and feature the telling line “I’m so sick and tired hanging around with dogs like you.” It would mark a turning point in his songwriting career, prefiguring the more emotionally expressive style of his solo album. Keith was still as vulnerable to Anita as he was to junk. Everybody else Keith hung out with was in the drug world. He was surrounded by creeps and dealers who spent the majority of their time trying to hustle him.

Before continuing to record Emotional Rescue in Paris, Keith took a vacation in Florida with Lil, Freddie Sessler, and Sessler’s new girlfriend, Terry Hood. Having lost the anchor of his family, Richards stumbled through the second half of 1979.

TERRY HOOD: “Keith is a very sensitive person and can be very emotional. He is a very interesting character, a bunch of complexities but really a very old-fashioned person. He has a lot of very interesting perceptions and sees life from different angles from being at the same time old-fashioned and sensitive. A lot of his sensitivity used to come out when he was stoned. Sometimes he would talk about the death of Tara in a roundabout way and he would get very emotional. He was very romantic, very big on flower petals on the floor in the bedroom. One night, I remember, we got flowers for the room for him and Lil. They were like confetti on the floor and he came out and went to the refrigerator and took out a carton of chocolate milk. He had had a bath and he had a box of Oreos under his arm and he was heading out the front door. I said, ‘Where are you going?,’ because if he went outside the building there was a security lock and he wouldn’t be able to get back in. I said, ‘You don’t want to go out there, you don’t have a key.’ And he lay down on the floor and said, ‘You know, these are my stage pants.’ He’d been up for a few days. I said, ‘Don’t you want to get in bed or let me put a pillow under your head? You look like a gypsy down there.’ And he said, ‘It’s a privilege to be a gypsy and be comfortable and to lay your head wherever you are.’ He’s one of those great storybook characters. ”

On October 26 Richards and Jagger flew to New York to mix Emotional Rescue. They continued arguing over the selection of tracks and mixes. Keith wanted to stay raw and take chances. Mick wanted to play it safe, go for mainstream pop success, and make as much money as possible. In November, in between periods of working with Jagger, Richards let out frustration of playing on albums by Steve Cropper, Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, and Ian McLagan.

Keith was like a man on the run trapped in a maze of trick mirrors. Everywhere he turned he saw people he loved disintegrating or disappearing, and he couldn’t do anything to help them. Since the New Barbarians tour he had stopped spending so much time with Wood. Ronnie was freebasing cocaine and losing his grip on reality. All Keith could do was turn away from the problem. Jagger had become embroiled with Bianca in a publicized divorce and had disappeared deeper into the jet set. The Glimmer Twins rarely saw each other or talked when they weren’t working. “Keith thinks the same as when he started, but I don’t,” Jagger noted. Keith’s life-style had taken its toll on Lilly. They continued to have a great sexual relationship, but she could no longer offer him a haven. There was no home he could go to and feel grounded except Freddie Sessler’s apartment in Florida. He visited Freddie frequently during this period, but for someone struggling with drug addiction, Freddie’s world was not a particularly healthy one. Freddie Sessler was undoubtedly a father figure to Keith, but as Keith tried to straighten out he would often become annoyed by Sessler’s behavior.

Keith had always made a point of celebrating his December 18 birthday to the hilt. His thirty-sixth birthday, in 1979—despite the unsettled nature of his life at this point—would be no exception. One friend who shared Keith’s birthday commented, “Being a Sagittarius is not an easy sign. He’s got an angel on one shoulder and a devil on the other. It’s given him beautiful women and riches, but it’s also given him a lot of pain. His personality was split. Half of him wanted to take the dark path, half the light.”

A number of friends gathered in New York for the occasion. Bobby Keys was there. John Dunbar flew in from London. Keith was again on the trot for three days at a time. With a bottle of Rebel Yell in his hand and half an ounce of cocaine in his pocket he would crash out wherever he fell, then wake up several hours later and just party straight on with whoever could keep up.

David Courts, Keith’s jeweler, arrived from London with a special gift he had made: a beautiful, thick, funky silver ring in the shape of a skull. Keith became enamored of the ring and wore it from then on because, he told a friend, it reminded him of his own mortality and of the fact that we are all the same beneath the skin. He was wearing the skull ring that week when he met the one person who could fill the void left by Anita and Mick.

Patti Hansen was a feisty model with apple-pie looks. Trying to get Keith to move on with his life, several friends had urged him to call up Patti, who they thought could be the right woman and soul mate he desperately needed. They shared a forthrightness, a sense of humor, and working-class roots. “For a year before I met Patti,” Keith recounted, “every other night someone would say, ‘Oh, you should meet this Patti Hansen.’ I kept asking. ‘Why should I meet this Patti Hansen?’ I found out.” Jerry Hall invited Patti to meet Keith at his birthday party, which took place at the Roxy roller rink in New York, but Anita, who was hoping to get Keith back if he broke up with Lil, was there too. Further complicating the setup was the arrival of one of Keith’s presents, a renowned call girl who arrived naked in a limo with a big ribbon tied around her. The poet Jim Carroll, who had recently embarked on a rock and roll career and become friends with Keith, remembered the comedy: “When Anita arrived she immediately started screaming, ‘I want to see Keith now! Where the hell is he? It’s his party! I have his son here, for God’s sake! He wants to go roller-skating with his dad!’ She wasn’t looking as good as she used to, but she still had this incredible Teutonic presence and I think Keith still had the fear of God in him about Anita’s jealousies. When he finally came out of a back room where he had apparently been with his ‘present,’ Keith had to do a little shuffle himself. It was a funny night.”

But it was Hansen who won out. When Keith called in the middle of the night and asked her to meet him at a club, they finally got together. For the next five days they ran around New York in a limousine accompanied by an entourage, playing loud reggae music and stopping at clubs, record shops, restaurants, and other people’s apartments along the way. On the fifth day without sleep they wound up at a party at Mick and Jerry’s, but Patti felt like a zombie and decided to leave. Keith turned to Mick and said, “I’m outta here too, I’m going with this lady. ”

A limousine driver named Bernie Cohen who occasionally ferried the Stones around New York remembered one journey in which Keith was sandwiched between two people who spent the whole time trying to persuade him to buy drugs. Keith had fended them off but sounded more and more uncomfortable. Three days later Cohen found himself driving Keith around with Patti Hansen. He noticed that with her Keith seemed to be a whole new person, balanced and calm.

PATTI HANSEN: “When I first met Keith all I could think was: ‘This is a guy who really needs a friend.’ I gave him the keys to my apartment after only knowing him two weeks. There was no sexual thing going on. I knew he just needed a secret place where he could get far away from the madding crowd. It wasn’t love at first sight, though it feels like that now. It just sort of mutually grew. But he is the most romantic man. So romantic. I remember New Year’s Eve ’79 going into ’80. I came back from Staten Island in my brother’s Oldsmobile because I knew somehow I was going to see him. I just knew it. When I got to my apartment, there he was sitting on my stairs, waiting for me. Keith and I have never been apart on a New Year’s Eve since.”