28. THROUGH AND THROUGH

1993—1995

“To me the delight of making a record is putting people together and seeing what comes out, and not telling anybody, ‘It goes like this or that.’ I like the spark. Mick always goes, ‘Where’s A? ... Where’s Z?’ and I’m like, ‘I don’t know until we get there.’”

Keith Richards, to Sylvie Simmons, Mojo, January 2002

Back in 1989 when I started work on Keith Richards’ biography I made two basic decisions which defined the book. First, I decided to interview all the major women in his life, in the belief that they had had the profoundest influence upon him as a creative artist. Second, I decided to rely upon Keith for an accurate emotional history of The Rolling Stones. These choices ended up producing a successful book. And nowhere were they more richly developed, or do they more accurately reveal the history of Keith Richards and The Rolling Stones, than in the Nineties.

To remind you of where we came in: in 1989, after spending the majority of the Eighties in a stalemate, which brought the band to its nadir with Undercover (1983) and the aptly named Dirty Work (1985), Richards was forced by Jagger to develop his own solo career. After making a fine album and movie with Chuck Berry Hail! Hail! Rock ‘n’ Roll (1986) and his own solo debut Talk Is Cheap (1988), Richards pulled the Stones back together at the end of the decade, and took them into the Nineties with the groundbreaking Steel Wheels world tour. Having amazed everyone by this incredible comeback, however, the Stones had continued to confound all expectations by falling once again upon fractious times. Instead of capitalizing on the new markets opened up by Steel Wheels and taking advantage of their spanking new 1991 record deal with Richard Branson’s Virgin, ($28,000,000 for six new albums and the back catalogue from 1970) they careened to a halt. This was largely due to the endless personal problems within the band.

In 1993, after thirty years of being ostracized by Jagger and Richards, Bill Wyman quit The Rolling Stones. He walked away a healthy and wealthy man, his sense of humor still intact and showing, at least in public, no bitterness toward the group. He had long been a far more vital musical ingredient than was generally recognized, except perhaps by Richards, who revealed the rivers of emotion running through him when he later said that, as a result of this, he wanted to kill his erstwhile bassist. Perhaps what really got to him was that Wyman was not carried out on a stretcher in the manner of Brian Jones, Mick Taylor, Jimmy Miller, Keith Harwood, Michael Cooper and Gram Parsons, to name but a few who have fallen on the Stones’ killing floor. In the world according to Keith, you weren’t supposed to survive The Rolling Stones the way Bill did.

In defense of Bill Wyman, in 1964, when I was 13, I was not alone in seeing him as the coolest member of the Stones, not least because of the signature manner in which he held his guitar, at an almost 90 degree angle from the waist up, and for his great chiseled stone face. I remember how proud he was—in interviews—of his bass playing on the group’s second album. (You have to remember circa ’64 McCartney also carried his bass at a 75 per cent angle.) If you take a journey through the Stones’ catalogue and focus on Wyman’s contributions you will discover that, apart from making numerous contributions in the studio—including the opening chords for “Jumping Jack Flash,” for which he received no credit—the way Wyman walks through changes on the band’s first 20 studio albums has at times the inexplicable beauty of genius.

Bill also best verbalized how one of the vital distinctions in the Stones’ sound was created by the tiny extra pulse of time they took to make those changes, by following the lead guitar player rather than the drummer. A good deal has been written about Charlie Watts’ appropriation of jazz techniques in the lovely light drumming that has always given the Stones a slightly more R&B than R&R feel. Wyman deserves as much credit.

Meanwhile “the new boy” Ronnie Wood, who replaced the runningfor-his-life-with-a-monkey-on-his-back Mick Taylor back in 1974, was still teetering on the edge of destruction. This was perhaps best exemplified by the occasion in 1991 on which the gormless Ronnie broke his leg in a car crash and then, while flagging down help, broke the other one. When I interviewed Mick Jagger at the Pierre Hotel in New York in 1974, the day before he flew to Munich to start work on It’s Only Rock ‘n’ Roll (the first album Wood appeared on), I asked him what the Stones would talk about after travelling all over the world but not seeing each other for several months. Jagger fondly described his friends as “men of few words.”

This now appears to be something of an understatement. Sifting through interviews with all of the Stones over the decades they share only one leitmotif: Bill and Keith “never talked” about the fact that Bill thought Keith hated him until 1978 (15 years into their run). Mick did not know what Keith really thought about his drug problems because “we never talked about it.” Keith said he “never talked” to Mick about his problems with women. And poor Ronnie Wood “never talked” to Keith or Mick about being denied partnership in their firm for 19 years, despite having sacrificed his talent and a large part of his heart to playing the thankless catalytic role between Richards and Jagger that had killed Jones and all but finished off Taylor.

Ever since he had joined the Stones as a hired hand on their 1975 tour of America, Ronnie had been on a salary. Compared to Keith, with whom he had attempted at times to keep in stride, he was a pauper. Ronnie stayed because he believed in the music, and understood his at times vital influence on the delicate Jagger—Richards chemistry. He received no such recognition from Jagger. As far as Mick was concerned, Ronnie’s days had been numbered for a long time.

To add irony to irony, while Wyman and Wood dealt with their conditions as best they could, the other members of the band appeared to be in the best shape they’d been in for many years. For each of them Jagger’s insistence on their solo outings had paid off in spades. For Charlie Watts, forming his jazz band, making a well-received record and undertaking a world tour had been sheer joy. It had also made him much more appreciative of the work Mick and Keith had done to keep the Stones together. Keith had never seen Charlie happier than he was in 1993. Mick had suffered the most from attempting to make it on his own, because he had tried to do just that rather than learn from stretching out like the others. He had badly miscalculated what it took to make a great record, or do a successful tour. However in 1993 he had his one successful solo album, Wandering Spirit. Consequently he too felt a certain satisfaction combined with a new appreciation of what he could do inside the Stones.

As for Keith, he had undoubtedly gained the most by going solo. With the Winos he had been able to develop several skills. He finally succeeded at singing lead vocal on more than one number live. He had in fact carried the entire Winos show night after night around the world. Now his tender, romantic, bluesy voice would become tantamount to a newly discovered instrument. Even more importantly Keith had always seen himself primarily as a record maker. For the past 15 years he had had to fight Mick every step of the way through the making of Stones albums. With the Winos he had been able to call all the shots. Having done that twice it was highly unlikely that he was going to play second fiddle to Mick in the studio again. Lastly, although he wouldn’t be able to sustain the Winos past ’93 (they had by then fulfilled their purpose), while working with them, he had formed a small commando-like unit with whom he could go into any studio in any situation and control the final mix. “We came back with a lot more experience and a lot more air between us,” Richards recalled. “We all learned a few things about being out there on our own, including Charlie, which is probably one of the most important things. I learned what it means to be a frontman. Charlie had a lot more appreciation for what Mick and I had been doing, running the Stones between us. Positive lessons got learned.”

Thus is was that when Keith and Mick met in London in February 1993 they eagerly agreed to pull the Stones back together. This decision, of making another album and going on a vast world tour that would have to outdo what they had done on Steel Wheels, set up the kind of ballsy challenge that had always brought the best out in Keith, and he threw himself up against it. When it came to making albums, his two greatest catalysts had traditionally been Mick Jagger and a crisis. Now he proved true to form. Indeed, Keith Richards had few better innings than during the April to December 1993 period, in which he put all his talents to work at welding all these disparate elements once more into a great rock ‘n’ roll band.

Unleashed by Jagger in an April—May songwriting binge in Barbados, Richards came up with bits and pieces of around 150 songs. In fact, in his favorite phrase of the period, they were “incoming!” so thick and fast, he later recalled he feared being buried in an avalanche. His theory of how he wrote them bore an uncanny resemblance to the explication of the Navajo Indians, who talk not of writing but “catching” a song.

RICHARDS: “Writing songs is a peculiar practice ... I am convinced that—being an artist—you pick up things for which you have acquired a sensitivity. You develop a sense for it, you grow antennae. That’s all there is to it. I feel I’m just an antenna. The songs are already zooming through the room and I receive and transmit. I sit and play my favorite Buddy Holly or Otis Redding songs, no matter whether on the guitar or the piano, and, with a bit of luck, something suddenly happens and it emerges. You’re only the transmission, but you’re off on your own track. In fact the best songs often come from accidents.

“There are musicians who make faces when they miss a note. I am glad when it happens and I think: ‘Hang on, that may be the birth of a new song.’ Analyze your mistakes, learn from your mistakes. The songs are babies, whom you nurture—as well as you can—and you see them grow up.”

Charlie, Mick and Keith were so enthusiastic about the crop of new Stones babies born that spring that by the time they flew out of Barbados on May 18 they felt as if they were riding the beginning of a potential tidal wave. While the others flew to London, Keith returned to New York. On June 4, hot off the Barbados binge and with the kind of timing that had become a hallmark of his career, Richards represented himself and Jagger at their induction into the Songwriters Hall of Fame. It was, he would later say, the only award that really meant anything to him.

RICHARDS: “The trophy was signed by Sammy Kahn, one of the best songwriters of the twentieth century. On his deathbed he said, ‘I want to include Keith in the Hall of Fame.’ I found that really touching, and I am in good company there—Irving Berlin, George Gershwin and many more.”

In his acceptance speech Richards said, “There was really just one song ever written. That was by Adam and Eve. We just do variations.” He was equally succinct about his ambitions.

RICHARDS : “I just don’t want to see the Stones grasping hungrily to be up to date and have hit records, I just want the Stones to do the best they can. They’re the only ones who can do it. I want to make really good stuff. If we get hits out of it fantastic, but if not they’ll be damn good records, and they’ll still last, and they’ll be around a long time.”

Having dispatched with this pivotal moment of 1993, Richards next turned his attention towards putting together what he dubbed The Rolling Stones Mach IV and “the best band you’ve ever had.” The first order of business was to take care of Ronnie. The long Jagger—Richards struggle for control of The Rolling Stones had always pivoted around loyalty. Whereas Jagger took the economist’s view of personnel, discarding them like used handkerchiefs once they had satisfied his needs, Richards rewarded long time loyalty with long time employment. In the week of June 21—25 when Charlie, Mick and Keith met in New York to audition bass players, Richards and Watts presented Jagger with an ultimatum : Ronnie Wood was finally voted into The Rolling Stones Inc. as a junior partner. Now he would earn a share of their profits and have a vote in band decisions. A much relieved Wood, who had remained conspicuously absent for the first half of the year, spending in fact more time with Rod Stewart than Keith, responded by offering his house in Kildare, Ireland as a base for the band to rehearse for the upcoming recording sessions.

In an unprecedented move, before going into the studio to record the album, Keith put the band through eight weeks of rehearsals and preliminary recordings at Ron Wood’s house between July 9—August 6 and September 4—30. There were several reasons for this. First and foremost was the need to work whoever would replace Wyman into the band. Secondly, the five-year lay-off between Steel Wheels (1989) and the new album Voodoo Lounge (1994), was the longest the band had ever taken. Furthermore they were determined to try extra hard to develop what they had started with Steel Wheels. Each man wanted to stretch his abilities. “This album was different because we spent a lot of time writing the songs and playing them before we went into the studio, much more than we had done for many years,” Richards pointed out. “But it was also like starting again. Especially with Bill leaving. And I knew it had to be a special one. The whole point of going through Steel Wheels and getting back together was that we had to build on that.”

This was the first time since their fabled 1971 Exile sessions in the cavernous basements of Keith and Anita’s chateau, Nellcôte, on the French Riviera, that The Rolling Stones had spent months working in one of their member’s homes. To make matters even more familial, Keith moved into the flat Ronnie had built for his mother above the garage. Within hours the place had been converted into Keith Richardsville by his commando road crew. Classic reggae poured its healing sounds from state of the art sound equipment that traveled with Keith wherever he went. Purple, mauve and violet scarves wound around antique lamps, candles illuminated the room, burning joss sticks and joints struggled for room in crowded ashtrays. Bottles of vodka, orange squash, ice buckets and glasses nestled among stacks of magazines, books about Nazis (they made him laugh), newspapers and notebooks on every available surface. Elegant stage clothes, in particular a full-length tiger skin overcoat costume, hung next to tasteful designer jackets in the closet. Keith’s guitar tech, a highend rock equivalent of Bertie Wooster’s Jeeves, with the unlikely name, considering Richards’ opinion of the French, of Pierre de Beauport, saw to it that Richards’ extremely valuable collection of rare and beautiful antique guitars, which oft moved Keith to composition mode, alongside street fighting models ready for action, were well oiled and near at hand. De Beauport guarded them with his life.

During the Barbados sessions Keith had rescued an abandoned kitten from a rainstorm and promptly dubbed him Voodoo. Ever since, wherever he set up camp, in the studio, the rehearsal hall, on an airplane, train, bus, or in a hotel suite, Keith’s domain became known as the Voodoo Lounge. When he tacked up the Voodoo Lounge sign in the window of Ronnie’s spare flat that early July evening and Rolling Stones music began to drift out into the Irish night, the album’s soul began to take root. “The atmosphere,” Richards recalled, “was very much like Exile On Main St. And I think it paid off.”

At the start of rehearsals Keith turned his attention to Mick, perceiving accurately that after the critical and commercial beatings he had taken on his solo efforts his lead singer needed to regain some confidence. “I am going to give you the best band you’ve ever had,” Keith promised Mick, “but you’re going to have to rise to the occasion, and you’re going to have to play a lot of harmonica.” At the time Richards explained that, “The more Mick plays the harmonica the more differently he sings. Soon instead of thinking of it as two different entities, he starts to sing the way he’s blowing the harp, he phrases differently. Every day before he’d even come into rehearsals he was doing two hours playing harp with Charlie. And I could hear it paying off a lot in his singing too. And I think by getting him to play we’re back, because I love the way he’s singing now. I’d say, ‘Wow! The man’s back. He’s got confidence!’”

Having set Jagger on course, Keith turned to Charlie. He was immensely impressed by how much the drummer had grown.

RICHARDS: “He is such fun to play with and he is so on right now. What I’ve always admired about musicians is the way that when it’s slamming a bit you look at a guy and he’s playing effortlessly, just as if he’s having a cup of tea. Charlie’s always been elitist and arrogant, but the guy just keeps on getting better and better with less and less effort. I really admire that.”

The first new boy in the Kildare sessions was the producer Jagger had selected. Don Was would, like the great Jimmy Miller, become not only the conduit between them, but he could also jump into the fray as a musician on the floor. Was now joined them in selecting the songs from the Barbados sessions to record.

RICHARDS: “Don’s first contribution was, ‘You’ve got a hundred songs here. We have to choose! Let’s cut this down to half to start with, and then eliminate.’ It was his job to hone down the balance of those 150 songs that had almost buried us!”

Don was a terrific organizer. A local rock writer at several sessions recalled “a loose atmosphere. He seems to run a very nice program, from the meticulous sound design, through the food coming at precise times, to just creating a really good vibe.” According to Keith, “To the Stones it was a real plus to have a guy who knew how things were played. It helped to keep his mind on what he was doing. Don Was slotted in beautifully, and he also handled the personal stuff really well. I can’t think of other sessions where ideas were popping up, things were that loose and free.”

When four more weeks of auditions failed to turn up a replacement for Wyman, Keith hit on a novel solution. Buttonholing Charlie after a long night’s work, he told the astonished drummer that, on this occasion, he had been pinned to make the auspicious choice. It was, as Richards later noted, one of the best decisions he made that year. Because, despite much hot if humorous protest, Watts rapidly selected the thirty-something Daryl Jones, whose credentials included five years with Miles Davis and service in the studio and on the road with several major acts including Madonna. He might not have looked like a Rolling Stone, and he would certainly never become one, but once a few essentials, like who to follow, had been ironed out, Jones fitted into the music with piston-like precision. Keith gave thanks and praise.

RICHARDS: “That was a potential ‘make me nervous’ situation; finding the right guy was all important. You change the bass player, you’re changing your engine room. It’s been a long since I’ve had that much input from Charlie. But the way Daryl and Charlie hooked up from the beginning was a joy to me. And I’ve got to say, Daryl Jones—hey this guy makes a big difference too. Mr. Jones sounds better than I’d hoped for. In fact, by the time we went into the studio in Dublin to record, the band was really playing together.”

The Stones’ choice to rehearse in Ireland had been motivated by Woody’s offer of accommodation at his house and the use of his home studio. Recording at U2’s Windmill Lane studios in Dublin, between November 3 and December 10, 1993, was equally convenient, and there was the added bonus of benefiting from the country’s lenient attitude towards taxation of artists of all persuasions. Also, Dublin was in the south and largely unaffected by the ongoing guerrilla war violence in the north, a factor which went a long way towards explaining its growing economic and cultural renaissance. However, for the most part, wherever they set up camp the Stones, especially Keith, lived inside their own minds and world, rarely emerging except to go to the studio. And once he got into his groove, Keith dispensed with even these trips, sleeping in the studio, becoming, as he put it, “a mole.”

Richards felt that one of the Stones’ greatest strengths was that they continued to record in the manner in which they had started. “You get Duran Duran come down for a day,” he recalled of a mid-Eighties session, “and say, ‘What are you doing in that room together?’ ‘It’s called playing music, man. It’s the only way we record, you snotty little turd.’ ” That was one reason why the room was so important to him, why it too was an instrument.

DARYL JONES: “For me, most of this record was done by laying tracks down with everybody playing. Everybody played, we learned the song, and we cut it. We’d come in the next day and see if we could beat the take we did yesterday. By this time everyone is learning the song better, and different things start to happen when we play it.

“Every once in a while Keith just seems to like to stir it up a little bit, get everybody’s blood going. It works. It’s funny. He says it’s deliberate, but I think it’s more really who Keith is. Sometimes he just decides that, ‘everybody else is going that way, and I’m going this way.’ It’s part of his nature.”

DON WAS: “I don’t think the kind of sparks that fly between Charlie and Keith happens in bands that have been together for two years. It takes decades of playing together to get that kind of rapport.”

With The Rolling Stones Mach IV up and running, the focus now shifted to the dynamic between Keith and Mick that created the Stones’ chemistry, taking the music to another level. Richards appeared to have a deeper appreciation for its delicate nature than Jagger. “It’s the hanging out together that makes the band—that delicate, fragile thing, the personality, the chemistry of everybody being actually able to tolerate each other,” he explained in one of his best descriptions of the band’s emotional engine. “You never know what’s going to happen, and that’s all that’s ever happened.

“The thing is you just hang around. Everybody thinks ‘wild party,’ as if there is some sort of big design going on. But really you just go to the room and see what happens. Sometimes Mick winds me up just to get me going, because he needs a bit of fire. And then I’ll yell and he’ll get angry, I’ll make him pissed off, and then we got the blood flowing. We kind of play with it in a way. Almost as much as we play the instruments, we play each other. Mick goes through his things. But to me Mick seemed to be ten times happier than I’d seen him in years. He was comfortable within the band and with what he was doing, and really into it. On Voodoo Lounge Mick and I were still getting used to actually enjoying working together again.”

Jagger tended to deflate Richards’ interpretations of their collaboration, bringing it down to a more mundane level.

MICK JAGGER: “Keith likes to think of himself as a tyrant, but to be perfectly honest he’s really just a pussycat, half the time he just does what he’s told. Don Was would just say, ‘Play it longer,’ and Keith would do it. Sometimes he gets very frustrated and doesn’t like what’s going on, and he’s very rude and gets too carried away with it unnecessarily, as if it’s really so important. But that’s just because he’s very short tempered.”

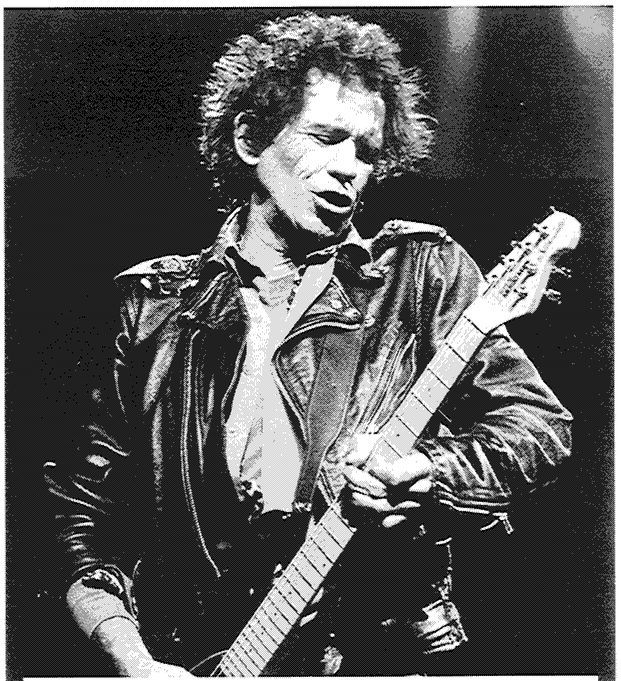

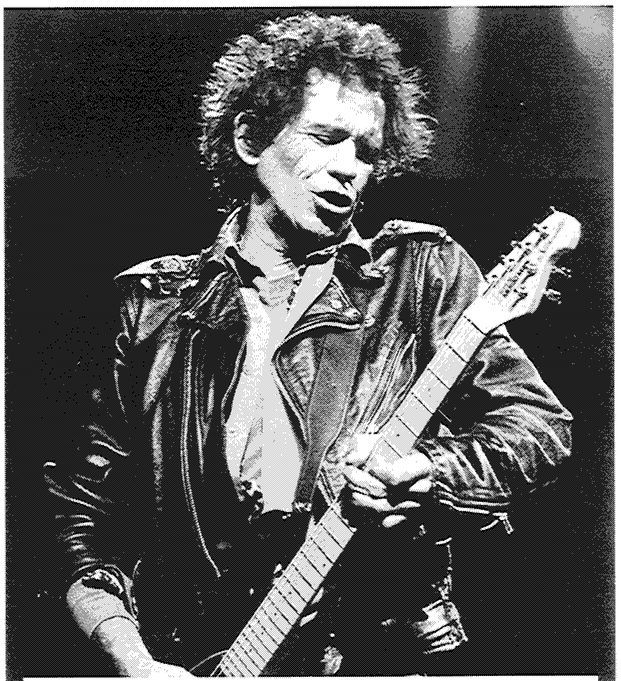

A trajectory of Richards’ lead vocals on Rolling Stones’ albums would be a good way to pin his growth as a songwriter, particularly as it currently climaxes with the trilogy (Steel Wheels, Voodoo Lounge and Bridges To Babylon). According to Don Was, “Keith’s playing is so intuitive, and it’s really generous. He processes information really quickly. Keith is at a real creative peak in his life right now. He’s writing some songs that are really different.” The pseudonymous James Hector wrote that “Baby Break It Down” “had Keith Richards stamped all over it, so much so that Jagger even sang it through the eyes of his partner.” He also commented that “Marianne Faithfull’s recent contention, (in Faithfull), that there was a definite sexual dimension to the Jagger—Richards relationship gave a new twist to the Everyly-like ballad ‘Sweethearts Together’ which found the pair face to face and celebrating their ‘two hears together as one.’” Richards’ “Slipping Away” had been voted best song on Steel Wheels by a critical majority. Now his “The Worst” would emerge as the truest romantic expression on Voodoo Lounge, and its companion “Thru And Thru” would once again be hailed as the album’s best song.

It sounds at first like nothing the Stones had recorded before. Charlie Watts’ cannonball drum shots defined the ballad’s stark, dramatic soundscape with the military precision of a quadrille. Meanwhile Keith sang lyrics stripped of the American dialect of rock in a startlingly real voice. When he grinds out: “I got those fucking blues/I got those awesome blues/Babe, I got those nothing blues,” he does not sound as if he is phrasing a traditional lament, but rather singing primarily and purely from the heart. And for Richards from here on one presumes that everything he does will be all about the heart. He may yet become our Sinatra, a blues singer whose perfect time is always 3 a.m., whose perfect place is always in a bar with a drink and a cigarette, telling stories about love and loss, stained through and through with the blood of romantic agony.

One person who found out the hard way just how important the track was to Richards was his clone in Guns N’ Roses, Slash. Keith had been lovingly developing the song with Pierre de Beauport and Charlie, not even letting Ronnie play on it. One night Slash was sitting with Wood in the studio as they both watched Keith listen to a playback. But when the song ended and Slash leaned forward, breaking into the silence eagerly, describing how he envisioned adding his blues licks to the end of the track, Don Was froze. He knew how this kind of remark could easily unleash a tirade from the outwardly tough but inwardly sensitive, some were now even saying mystical, genius of The Rolling Stones. As Keith’s eyes unbluffed, unreadable, periscoped disdainfully towards the unfortunate Slash, Was could have sworn they turned an inhuman, radiating black. But then Keith pulled back from the edge of blistering contempt and let it go, simply rasping, “I like ya kid, but don’t push your luck. You ain’t coming anywhere near my fucking track.”

After a few more muffled references to “guitar apprentices” in the room Richards turned away, pouring himself back into the work. “Keith is not a guy to hide his feelings,” Was pointed out. “He left no doubt that he didn’t appreciate the suggestion. He knew very clearly what he wanted to do on the record.”

The bottom line was that friction still produced better rock’n’roll than harmony, and the Stones were still able to stir up healthy doses of friction on demand. Perhaps the greatest compliment that can be paid these artistic collaborators is that after so many years of commercial and critical success they were still able to play each other more creatively than anyone or anything else. Someone asked Keith if they still fought over their records. “Was Sharon Tate’s living room a mess?” he shot back. “Of course we still fight, but,” he persisted, “it’s also an argument within yourself. If we had tried to cut any more tracks off the album there’d have been shooting, we’d have killed each other. None of us back down easily. We did a lot of arguing. That’s a process I’d love to film—the Stones sitting around a room arguing—with a little spy camera.”

Perhaps Richards best summed up the essence of the difference between himself and Jagger with this simple image plucked from the nexus of his childhood: “There’s Mick in there trying to be democratic: ‘Put your hand up for this song, your hand up for that song.’ I sit in the back, trusting that the album will find itself in its own way, putting all my hands up for everything.”

In January 1994, Keith flew out to LA to work with Mick and Don on the crucial mixing stage of the album. Mixing had been the battleground between Richards and Jagger throughout the Eighties. This time, however, control of the final cut eluded the Glimmer Twins. By all accounts the raw, rich blues album they had cut in Ireland, of which witnesses believe even Ian Stewart would have approved, was refitted by Was to meet the Stones new record company’s demands for a hit.

Back in 1991, when Richards persuaded the band to sign with Richard Branson’s Virgin, the label which released his solo albums, he must have been looking forward to working, for the first time in his life, with a record company executive who was a contemporary he could look in the eye, and a true fan. Imagine then his astonishment when, shortly after purchasing the Stones’ contract, Branson used it to up the price of his label, then sold it in order to finance his airline. We all move on. The Stones knew that better than anyone, but they were not usually the ones left behind, and left behind in this case to carry the burden of now being owned by a global conglomerate, Thorn EMI, whose executives made their decisions in rooms so far removed from Keith’s Voodoo Lounge they might as well have been on another planet. Meanwhile Was won a Grammy for his production of a Bonnie Raitt album that month, making him a harder man to argue with. Between January—Arpil he refitted the tracks, snipping out an African influence here, burying an Indonesian inflection there, and thereby ironing out their commitment to roots R&B and pulling them more into the mainstream.

The fate of their new album was, Jagger would later comment, a classic case of corporate rock. By attaching the making of the first album in their new contract to the mammoth preparations of a world tour, largely Jagger’s responsibility, they had by definition accepted corporate input. And in the end who is to say who was right and who was wrong, or if those terms have any relevance here. The Stones may have made a splendid piece of art in Ireland, but they also needed a hit. On its release in July 1994 Voodoo Lounge reached number one in England and number two in the US and made the Top 5, often number one, in 34 other countries. It sold 5.2 million (or more depending on whose figures your read) in its first year and won a Grammy in the US as best rock album of the year. It was a fuller, more united work than Steel Wheels. Furthermore, whatever was said after the fact, Don Was came back to make the next three records.

The Stones’ success in the middle of the Nineties had as much to do with changing trends in music as with their reputation and talent. In the US grunge, led by Kurt Cobain’s Nirvana and Eddie Vedder’s Pearl Jam, celebrated the Keith Richards image of the damned Byronic hero caught up in the coils of the romantic agony that had dominated the popular imagination in the arts since World War II. Grunge peaked in 1992, but Cobain’s suicide in 1994 made the timing of Voodoo Lounge’s release in the States, as well as its use of Haitian voodoo symbols and Keith’s immaculate sound bite, “String us up. We still won’t die!” in its press package, too perfect to be true. Meanwhile in the UK the Britpop movement, spearheaded by the Beatles—Stones like competition between Oasis and Blur, brought the celebration of English rock (but not significantly R&B), and in particular the guitar God who had been out of favor in the Eighties, back into focus. From the early Eighties onwards the band had been repeatedly ridiculed in the media for being a bunch of cartoon dinosaurs, holding onto a system of values long relegated to the refuse heap of history. Now, suddenly, in 1994, in an about-turn as rapid and all encompassing as punk, The Rolling Stones were once again celebrated as princes and deified as gods in the rock’n’roll pantheon. Once again they became the ultimate moulds for young white boys who wanted to rock.

Voodoo Lounge was a good Stones album, as good as its closest sister Goats Head Soup, but its position at number one in the UK and many other countries was in all fairness the result of team work. When Richards said they had learned over the years to play each other as much as their instruments he also meant play the game. The Rolling Stones after all no longer belonged to their hardcore fans or even to music aficionados. In the Nineties they really did mutate or metamorphose, they became champions of the spectacular, an act whose resonance—like Warhol’s—was equally due to what it produced, what it had done, and what it stood for. In the bigger picture Keith pointed in the right direction when he said that the band’s greatest success was the role it played in bringing down the Berlin Wall. Perhaps the most important thing the Stones did in the Nineties was add to their tour itinerary Central and South America, Japan and South Africa, making planet rock.

Beyond that the relevance of what happened within the band in the mixing of Voodoo Lounge was the relative harmony it created between Jagger—Richards. This was personified by the song “Sweethearts Together,” the Everyly Brothers—style duet on which Keith and Mick fulfilled Andrew Oldham’s 1963 vision of two guys singing to each other. Moreover, it was their two hearts, as opposed to their two minds together, that they celebrated, thus focusing the emphasis of their collaboration not so much on the third mind as the third heart. Lastly, in terms of military installation, Keith’s interest in the final product focused on how well disciplined its sound was, and how that was a result of his working with Don Was, the engineer Don Smith (his man), and his guitar partner from the Winos, Waddy Wachtel. Here was the first edition of Keith’s commandos. Tellingly he remarks that it had been difficult to work in the Eighties “because a lot of the material Mick wanted to do was not particularly guitar oriented. In actual fact, there’s quite a lot of guitars on those tracks, but the key is their separation. There may be six guitars on some of those tracks, but they’re not on all the time, they’ll be shifting. Two of them will be almost identical but one will just do better, try for a certain lick in one place, and we just pull it up. There were more separations between the guitars than there’s been lately I think, just more direction really.”

The real results of the mixing of Voodoo Lounge would become evident when Keith fitted himself for the battle that would ensue over Bridges To Babylon, Richards’ greatest achievement of the Nineties with The Rolling Stones.

The Voodoo Lounge world tour broke into six separate legs: the United States and Canada, August—December 1994; Central and South America, January-February 1995; South Africa, February 1995; Japan, March 1995; Australia and New Zealand, March—April 1995; and Europe, May—August 1995.

On June 20 the band gathered in Toronto, the base of their tour promoter Michael Cohl, where they set up camp and rehearsed in a boys’ private boarding academy, the Crescent School.

RICHARDS: “The germ of the idea for what would become the live album, Stripped, came from these rehearsals. We were rehearsing for six weeks, doing five or six maybe 10 or 12 hours a day in there, listening to playbacks every night, just to check the sound and do the usual night watchman bit. They started to sound good. The tracks had a certain different feel—the guys think they’re not recording, they’re working and playing and having fun. At the beginning of this tour we realized that if we didn’t watch out we’d end up with Voodoo Lounge: Live At The Stadium. Both the band and Virgin said, ‘Nah, enough already.’ OK, so now I’ve got a negative directive. I know what we don’t want. But what do we want? That’s where the germ of the idea started.”

According to Don Was, Charlie was the driving force behind these rehearsals. They started each night around 10 p.m. and finished 10 or 12 hours later, whenever Keith collapsed, but Charlie was still going strong. The addition of Daryl Jones had given him a new lease of energy.

The Rolling Stones toured the US from August 1 to December 18, 1994. As always at the start of an American tour, despite the months of rehearsals they played so poorly Jagger was reduced to apologizing to the audience. It was mostly a result of working Jones into the line-up. They had apparently not “talked about” the fact that The Rolling Stones followed their lead guitar player not their drummer. (If only they’d had Bill at rehearsals coaching Jones in some of the basics.) For the first two weeks this caused a shambles when it came to starting and stopping each song. They finally found their groove in mid-August. It was around this time, after a freak thunderstorm produced the best show of the US tour, that Keith started talking about playing with God.

RICHARDS: “God joins the band whenever we play outdoors. Suddenly there’s this other guy in the band, showing up in the form of wind and rain. And we’ve got to be ready to play with him. Who does he think he is? I can’t wait to meet him. Doesn’t he know who we are? We’re The Rolling Stones!”

From the critics’ seats the band got good reviews as they swung into the music like a hard-edged blues combo. “The show is a magnificent crosssection of big hits, rarities, new tunes and choice covers,” wrote Edna Gundersen in USA Today. “The battering ram of a show finds the Stones rock’n’rolling like hellions on wheels.” Keith said they owed their newfound commitment to the varied solo careers, and the fact that they really enjoyed playing with each other more than anybody else.

RICHARDS: “Every single one of us had his own experiences with regard to music and a life without the Stones and then incorporated them into our joint work. And despite all those years of ups and downs we liked playing together. It’s the hanging together that makes the band—because you wear yourself pretty ragged on the road. ‘I hate you forever,’ we’ll say one day, but forever lasts 24 hours.”

The major addition to the Lounge tour vis-à-vis the Steel Wheels tour was an enormous video screen behind and above them.

RICHARDS: “Every time we come back to touring they have more high-tech gizmos that you’ve got to learn how to work. Over the years we’ve had to learn how to do it bigger and bigger. It’s like some Frankenstein monster, some huge juggernaut. And you can end up working for it rather than it working for you. It can get so fucking big you can’t do what you want anymore, which means you have to deal with a whole lot of frustration. Now we’re working for the huge stadium screen. The first ten, 20 rows may be looking at the stage, but everyone else is looking at the screen, which means the band are working for the cameramen. I’ve always been suspicious of TV. I’ve always found music and video to be an unhappy marriage. MTV turned it into a money-making proposition and music suffered from it in the Eighties, when what looked good was more important than what sounded good ... Good music comes out of people playing together, knowing what they want to do and going for it. You have to sweat over it and bug it to death. You can’t do it by pushing buttons and watching a TV screen.”

On September 7, the Stones played the MTV Awards ceremony where they were presented with a Lifetime Achievement Award. The same month, while they were in Boston, they received the news that Nicky Hopkins, who played piano on many of the Stones’ best albums, had died in Nashville, aged 50. Before the month was over Jimmy Miller, who had produced many of those albums, died of liver failure at 52. These deaths did not leave the band unaffected, but overall this was probably the happiest tour they ever did.

RICHARD: “I’ve never seen Charlie Watts so happy on the road. He’s a happy guy normally, but the road can get to anybody. He’s brought his old lady with him, and I think he’s enjoying playing with Daryl, and playing with the Stones. And I have improved as a singer thanks to the Winos. They really put me under tremendous pressure and I have learned when to pause, how to play and sing at the same time.”

Keith was particularly impressed with Mick’s performances.

RICHARDS: “During Mick’s harp solo on ‘Out Of Control’ I stand over him provoking him, saying, ‘Come on motherfucker! Blow it, come on!’ He performed so well, he sang so great. There’s a hundred-odd shows in varying conditions and he hung in.

“I’m very impressed with the way the whole band dealt with this tour, because it’s seemed to go on a steep upward plane. There were no real highs and lows. Usually with a tour it’s a good show, great show, terrible, average and they sort of build up. This has gone so well from a musical point of view, from a performance point of view. I guess that’s why they’re going to continue. If you set it up and said this is the way you’d like it to be, it’s gone better. Quite honestly, it’s never been better really, it’s been amazing. The guys are just on. It’s one of those indefinable things. Maybe it’s because this hasn’t been much of a show year. All the energy is there with the audience. Now and again we just sort of step right into a perfect frame.

“It’s almost as if we had a mission. You can’t help it if it’s outside our control. As long as the others are around we’ll go on until we can’t go on any longer. Nobody ever wondered why the old blues men were on stage until their old age. We play because we can, we do what we have to do. Our motto should be, ‘We do what we do best.’”

On Halloween night, at Oakland Coliseum, Keith looked out at the audience and remarked, “You look great. I don’t have to wear a fucking costume, every night of my life is like Halloween.” The US tour ended in Vancouver on Keith’s 51st birthday, December 18. He celebrated it with the knowledge that having earned 140 million dollars, the Stones had just completed the most lucrative US tour, or for that matter any tour, in history.

January and February 1995 were spent touring Central and South America for the first time. On January 14 they commenced a four-night stand at Mexico City’s Rodriguez Stadium. Their February 4 show in Rio de Janeiro was seen across the continent on TV Globo, Brazil’s largest network, by an audience of 100 million people. Fan hysteria reminded them of the early days when they couldn’t walk down the street without attracting a passionate and hysterical mob. They were in the headlines every day. It was as if they had invaded the continent. And the shows were outstanding.

RICHARDS: “The band is getting better and better. The guys are knocking me out and that makes me happy. And if I’m happy it keeps everybody happy, because when I’m unhappy, forget about it.”

On February 9, 11, 12, 14 and 16 they played Buenos Aires River Plate Stadium, and also attended a reception in their honor with the British Ambassador given by President Carlos Menen. On the 19th they played Santiago, Chile.

In March the Stones flew to Tokyo for their second tour of Japan. The band rehearsed in Tokyo and then played the Tokyo Dome on March 6, 8, 9, 11, 14, 16 and 17. In between shows the hardest working band in rock went into EMI’s Toshiba studio, where they were joined by Don Was, to record some acoustic renditions of classic songs for a possible tour album.

RICHARDS: “The spirit of the playing was different from the other live albums, because most of the tracks were recorded in small rooms. The whole band is thrown in with no overdubs. You’re live but there’s no audience. You catch guys unaware—that’s the feel on it. You get a chance to play some of the old songs again, maybe put in a few licks you wish you’d put in the first time.

“When in doubt if something doesn’t sound right I just brush on an acoustic guitar and see what happens. What it does, if you’re recording a band, is fill the air between the cymbals and all the electric instruments. It’s like a wash in painting. Just a magic thing. If something sounds a little dry or heavy or tight, put on an acoustic or maybe just a few notes of piano—another acoustic instrument. Somehow it will just add that extra glue.”

These sessions were also filmed, although the results were scrapped. On the 22nd and 23rd they played the Fukuoka Dome in Fukuoka, Japan.

RICHARDS: “I like Japan. There is something cheerful about Japan. You don’t really know where it comes from, but the people are extremely nice. They’ve cultivated some strange formality here. All this ‘Thank you, I will find out for you Richards San.’ It takes a few days getting used to it. And when you’re in the next city the people will give you funny looks, because you still bow when asking for a drink.”

On May 1 a planned concert in Peking was cancelled when authorities refused the band visas. “I get a long letter from the Chinese Government,” Keith recalled, “saying why I can’t come. Number One on the list is ‘Cultural Pollution’ and about Number 30 is ‘Will cause traffic jams!’ And in between is a whole load of other crap.”

In May, Keith rehearsed the band in Amsterdam for the European tour. This time they returned to their blues roots, putting together a club style tour for the summer. They also recorded and filmed four nights at Amsterdam’s Paradiso club, with 700 fans attending each night. The second night was transmitted to a huge screen watched outside by 75,000 fans in the middle of Amsterdam. Keith opined that they had been the best gigs the band had ever played. These tapes would be combined with other recordings, during rehearsals in Tokyo and Madrid, for inclusion on the live Stripped album of the tour, yielding an outstanding single of “Wild Horses.”

The European tour opened in Stockholm and included stops in Helsinki, Oslo, Cologne, Paris, London, Prague, Budapest and Berlin. As the “undisputed world champions of spectacle rock” they were welcomed everywhere as conquering heroes. Even British reviews were ecstatic. It was arguably the Stones at their best ever live. The only major negative note came in September when the German magazine Der Spiegel had the gall to make the appalling suggestion that The Rolling Stones had played through the European tour to backing tracks! “Call me whatever you want—junkie, criminal, cultural pollutant, but don’t tell me I don’t play live,” Richards exploded. “That’s the biggest insult in the world. First I want an apology from them, and then, no matter how much money we get from them it will be sent to the kids of Bosnia. I don’t even want to see their money,” he concluded.

On November 14, 1995, The Rolling Stones released a supposedly outstanding live album, Stripped. Recorded by Don Was at clubs in Amsterdam and Paris and during rehearsals in Lisbon and Tokyo it was the band’s version of the unplugged vein MTV had popularized so successfully with Eric Clapton, Rod Stewart, Aerosmith et al. The same month they released a CD-Rom of Voodoo Lounge and launched the Rolling Stones World Website, placing themselves squarely in the number one position worldwide mid-decade.

Of these ventures Stripped appeared to be the gem, although appeared was unfortunately the key word. Roch Parisien wrote that the idea of “taking it back to small clubs, live, lean and pared down without succumbing to the worn unplugged treadmill, seemed an inspired move. Unfortunately, the cover photo depicting a lean, determined leather clad combo in spartan black and white proves to be misleading advertising. Within the brave packaging lies a listless, lethargic, Dorian Gray bluff. Spongy keyboards gunk many tracks.” The cover of Dylan’s “Like A Rolling Stone” “remains pointlessly devoted to the original. There are lazy, somnambulant versions of etc etc,” a lot of which I have to say is true.

After doing the requisite round of interviews, successfully pitching the album at the Christmas market (it made the Top 10 in many countries), Keith flew down to Point of View overlooking Ochos Rios in Jamaica.