Barbara Bradford (originally entitled ‘Upspeak in British English’ (1997). Reprinted from English Today 51, 13.3: 33–6)

In this extract, Barbara Bradford discusses the nature and possible origins of an intonation pattern which appears to be increasingly common in the speech of many native English speakers, especially those of the younger generation. What she terms ‘upspeak’ has attracted much comment in recent years – not all of it favourable.

An examination of a novel UK rising tone, with reference to its use in some other Anglophone countries

This article reports on a small-scale study of the use of a particular intonational feature, sometimes referred to as ‘upspeak’, by speakers of British English. The term upspeak is used here to refer to the use of a rising tone in the final tone unit of a declarative clause where in RP a falling tone would be used. Its use seems to extend across geographical areas, social classes, the gender boundary and, to some extent, chronological boundaries, although it occurs most commonly in the conversations of those in their upper teens, twenties and thirties.

The article is based on observations of the occurrence of upspeak among British speakers in the mid-1990s and refers to speech data of a group of female RP speakers in their late teens and early twenties. The article suggests that upspeak has two main communicative functions and focuses on the interpersonal and situational factors which predispose speakers to use it.

Similar phenomena to upspeak have been documented in other areas of the English-speaking world in the last 35 years: New Zealand, Australia, Canada and the USA: see Britain (1992) on the occurrence of High Rising Terminal contours in New Zealand English, and references therein to research in other geographical areas. The present study provides independent confirmation of the existence and diffusion of this intonational feature in British English.

… The use of a final rising tone where a falling tone would be expected in RP is an established and well documented prosodic1 feature not only of upspeak but also of non-standard accents in some regions of Britain, e.g. in Wales and Northern Ireland and in the English cities of Bristol, Liverpool, and Newcastle, and the county of Norfolk. It is also characteristic of regional accents in other traditional English-speaking countries, as well as Caribbean, Indian and some other varieties of English. (See Cruttenden, 1986, p. 137 ff.) What is important here is that the distribution of the rises is more systematic in regional and varietal accents of English than it is in upspeak. The upspeak rule is applied non-systematically, i.e. upspeakers do not convert all RP falling tones to rising tones, even where the structural conditions for the operation of the rule are fulfilled.

An explanation frequently offered for any change in language use is that young people are influenced in their way of speaking, particularly in interaction with their peer group, by the accents of role-model characters in films, advertisements and television programmes made in Australia, USA and dialectal areas of the UK. In the case of the appearance of upspeak, the Australian soap operas ‘Home and Away’ and ‘Neighbours’ and the Merseyside soap ‘Brookside’ are suggested as the initiators, since both Australian and Liverpool accents are perceived as demonstrating frequent rising tones. Such influences cannot be totally ruled out as it is likely that many of those in the age group now using upspeak will have watched these soaps. It is suggested here, however, that if it is the case that Australian soap operas have played a part in the initiation of upspeak in British English, it is because British youngsters have viewed characters in the programmes using the equivalent of upspeak in Australian English. What could have been spread in this way would, therefore, not be an aspect of General Australian pronunciation as such, but an international feature of the intonation of young people.

However, there are at least two counterarguments to this TV influence theory. Firstly, the fact that from the full set of phonetic features which make up any regional accent only the steep final rises in pitch have been adopted by the upspeakers is problematical. The main difference between the Australian accent and RP is the vowel sounds and so one might have expected to detect evidence of, at least, some vocalic adaptations. Secondly, I have personal experience of a 23 year old who is not a current viewer of any of the TV programmes which have been blamed for the use of upspeak but who started to use it in 1996 after returning from four months living and working abroad with a group of young British people. The key point here, though, is that she watched both of the Australian soaps avidly during her teenage years but neither she nor her peers used upspeak at that time. None of this is conclusive evidence to disprove the Australian soap influence theory, but it does suggest that an investigation of interpersonal and social factors may yield more productive findings.

A description of intonation which in sociolinguistic terms identifies and characterizes the meaning contrasts conveyed by intonation features was developed in the 1970s from original work being done in discourse analysis (Coulthard, 1977). Previous approaches had described intonation in terms of a range of attitudinal significances (O’Connor & Arnold, 1973) or in terms of grammar (Halliday, 1967). The theory of discourse intonation (Brazil, Coulthard & Johns, 1980; Brazil, 1985) describes the forms and functions of English intonation in terms of the discourse context and with reference to the social setting. It describes and explains the communicative value of intonation by focusing on the decisions a speaker makes at each point in the developing conversation. These are subconscious decisions about prominent syllables, tone and pitch levels.

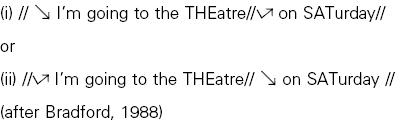

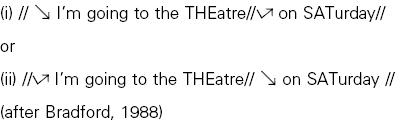

According to this model, tones (i.e., major pitch movements) can, in simple terms, be divided into two categories: those which finally fall (fall and rise-fall), classified as proclaiming, and those which finally rise (rise and fall-rise), classified as referring. The two types of tone can be seen to relate to a contrast in meaning. In general terms, the rising tone can be said to be used by a speaker for that part of an utterance which s/he perceives or presents as existing common ground between him/herself and the hearer(s) at that point in the conversation, whereas the falling tone is used for that part of an utterance which the speaker perceives or presents as new to the hearer(s). The speaker’s perspective on an idea, whether it is an idea already in play or whether it is a new contribution to the developing conversation will determine tone choice. This short sentence: ‘I’m going to the theatre on Saturday’, illustrates the meaning contrast of the finally falling and finally rising tones:

In (i) the fall-rise tone comes in the tone unit containing Saturday which signifies that Saturday is discourse-old at this point in the conversation, so this sentence would be a suitable response to ‘Would you like to go out to dinner on Saturday?’ The falling tone is used for the part of the utterance which contains ‘new’ information for the hearer, i.e. going to the theatre. In (ii) the fall-rise tone comes in the tone unit containing going to the theatre which signifies that this is information already activated at that point in the conversation so this sentence would be a suitable response to ‘Would you like to go to the theatre on Friday?’ The falling tone is used for the part of the utterance which contains the ‘new’ information for the hearer, i.e. on Saturday.

From this we can see that tone functions in discourse as a means by which participants indicate how they perceive the status of the information they are conveying in relation to the state of convergence between themselves. The finally-rising tone functions to increase the area of convergence and to lessen the conversational distance between them.

Upspeak is an intonational device used by speakers for two main communicative purposes.

First, it has an affective2 dimension, acting as a bonding technique to promote a sense of solidarity and empathy between speakers and hearers. (See also Britain, 1992, and references therein.) An upspeaker seeks to reduce the social distance between him/herself and the hearer(s) by exploiting the rising tone, conventionally reserved to convey the idea of common ground and shared experience, and uses it as an intonational strategy to present hearer-new information and simultaneously to project or expand the state of convergence between them. This exploitation of the intonation system has the psycho-social effect of making the speaker sound less assertive or authoritative.

Second, upspeak has an important referential component, acting as a means of signalling salient chunks of information, and thus encouraging the hearer’s continued involvement in the discourse. By presenting ‘new’ information as if it were part of ‘common ground’, a speaker indicates that the content of that part of the discourse is perceived to be of intrinsic or assumed mutual interest.

In this way, the speaker is able to provide cognitive stepping stones in the unfolding discourse to enable the hearer(s) to negotiate the stream of speech. This ‘directing to a focus of interest’ function may explain why upspeak occurs so frequently in narrative.

As a device for ensuring the hearer(s)’ continued involvement and interest in the narrative, the use of upspeak may be similar in effect to the use of fillers such as ‘Right?’ or ‘You know what I mean?’, which are used by speakers to check that their listeners are keeping abreast of the information flow or are sympathetic to what is being said. They are in use in many varieties of English; for example, ‘yeah?’ and ‘OK?’ are used in the USA and extensively elsewhere, Canadian English speakers often add an ‘eh?’, and there is a tendency in South African English to use ‘ya?’. Such fillers are pronounced with a steeply rising pitch movement and are located at the end of a falling-tone declarative, the declarative–filler combination producing a fall-rise contour which terminates with a steep and high rise. This leads us to conclude that the phonological form of upspeak, described earlier as a fall-rise with a steep and usually high terminating rise, is the conflation of a standard falling tone with the steep rise of a filler of the ‘Right?’ kind. In this way, the communicative force of the interrogative filler is intonationally incorporated into the declarative, making the filler itself redundant and reducing syntactic complexity.

Although upspeak in British English appears to cut across gender, the available evidence indicates that it is most prevalent among and first displayed in the speech of young females. It permeates the speech of young males only after becoming well established among females. Assuming that upspeak can in part be explained as an emotive bonding technique, this initial resistance on the part of males might be construed as an exponent of the assertive masculine psyche with its inclination to retain authority and control – in this instance by not exploiting upspeak to reduce speaker–hearer distance. In contrast, the females’ inclination to use it can be seen as a linguistic reflex of the female wish to appear approachable. It follows, then, that if a female is in a position of higher status than her interlocutor(s), or in a dominant role, but wishes her feminine identity to be taken into account, she would be inclined to use an intonational device which increased the area of convergence between them. One example of this affective function is the nurturing, non-authoritative speech of mothers to very young children, where the use of rising intonation patterns is well documented (Garnica, 1977; Ogle & Maidment, 1993). Upspeak does become a feature of the speech of some males once it is well integrated among the females in a community. Males may consciously or subconsciously choose to use this intonational device in situations where they wish to appear non-assertive and when they wish their contributions to be perceived as conciliatory rather than aggressive.

It appears that upspeakers are able to code-switch,3 using upspeak in one context but not in another, according to situational factors. Upspeak is initially a peer group activity, creating a speech community among the young. Its use is reinforced by the acceptance it brings, signalling in-group solidarity, a wish both to include and to be included. Speakers switch between their normal intonation and upspeak, according to their perception of the setting, using upspeak in situations where they sense or desire social cohesion and hearer empathy.

The fact that upspeak has an irritating impact on many people in Britain, particularly those of the older generation, may be caused, at least in part, by a misjudgement of the social situation on the part of the upspeaker and a misconstrual of the upspeaker motivations on the part of the hearer(s). If a psychological signal for social bonding is given by the speaker where a distance is required by the hearer, it can be perceived as out of place and even disrespectful. The negative reaction on the part of the hearer could also relate to confusion caused by the incompatibility of a declarative statement containing an interrogative intonational component. The fact that a young speaker may use upspeak for a length of time when living or operating in one social context and then discontinue when in another was stated earlier as a personal observation. This suggests that upspeak is transient in nature, a phase through which some young people pass.

However, just as upspeak crosses the gender boundary once it has become established in a community, it seems also to cross chronological boundaries. In the USA and the Antipodes where it is well established it has spread through the age groups and is no longer used exclusively by the young. The factors governing its use can be seen not to be exclusively age-related, then, but to be motivated by the social and interpersonal conditions of the speech situation.

Upspeak has been heralded by the British media as a recent aspect of language change possibly triggered by the influence of Australian soap operas on teenage viewers. It has been suggested here that it has been in existence in many parts of the English-speaking world, including the United Kingdom, for at least 30 years. Whether the geographically disparate occurrences of upspeak are totally independent developments or the result of contact-induced spread is an open but interesting question. Either way, the communicative functions of upspeak can be explained by reference to interpersonal factors and the convergence or divergence of conversational distance, and its expansion seems to have been conditioned in all cases by sociolinguistic determinants.

1prosodic: another term for supra-segmental, referring to phonetic features such as intonation, stress and rhythm.

2affective: relating to moods, feelings and attitudes.

3code-switch: the process of changing from one language or language variety to another.