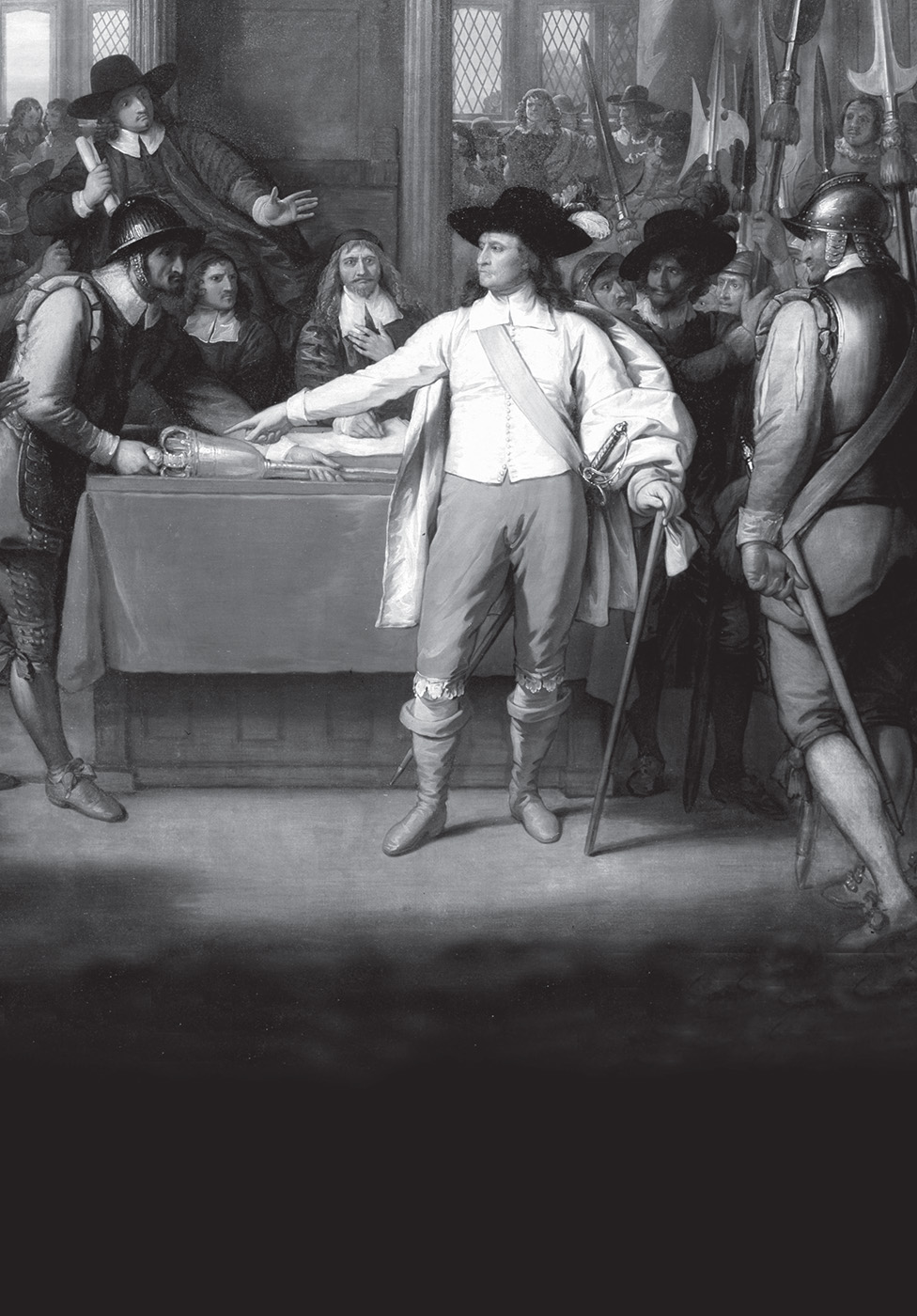

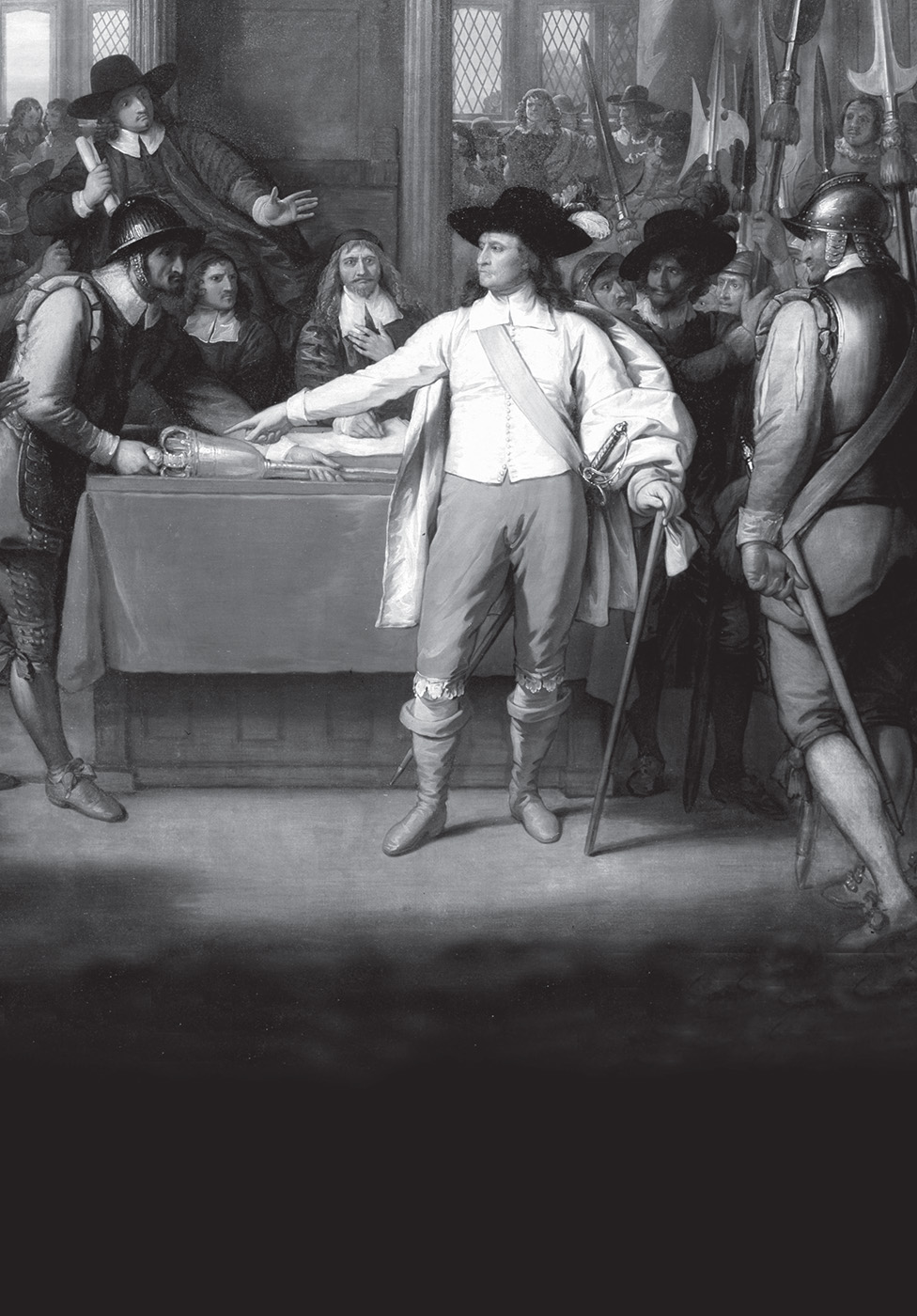

OLIVER CROMWELL

Speech dismissing the Rump Parliament, 20 April 1653

OLIVER CROMWELL

Born 25 April 1599 in Huntingdon, England.

Cromwell became a Member of Parliament in 1628 and on the outbreak of civil war he emerged as a highly competent cavalry commander. He was largely responsible for the victory at Marston Moor (1644). With Sir Thomas Fairfax, he reorganized Parliamentary forces into the New Model Army and won the important Battle of Naseby (1645). He was one of the first signatories of Charles I’s death warrant in 1649, and by now the most powerful figure in the country. He spent much of 1649–51 suppressing rebellion in Ireland, Scotland and at the Battle of Worcester (1651). The next seven years of his ‘commonwealth’ regime saw war at sea with the Dutch and Spanish, reforms to improve Irish and Scottish political representation (though parliaments were intermittent), the readmittance of Jews to England, and attempts at religious toleration. In 1657 he refused the crown, preferring his title ‘Lord Protector of England, Scotland and Ireland’.

Died 3 September 1658 in London. In 1661 his body was exhumed after the restoration of Charles II, and strung up.

In 1653, Britain was four years into its experiment with a military-republican government, following the years of civil war in the 1640s and the trial and execution of the Stuart king, Charles I. Since the later 1640s, the pivotal figure in the country’s politics had been Oliver Cromwell. An East Anglian gentleman-farmer and Puritan convert, Cromwell emerged as the Parliamentary cause’s military leader of distinction. His skill had proved decisive in defeating the Royalists, and his political arm-twisting helped ensure the ‘cruel necessity’ (as he put it) of executing Charles I in January 1649.

Despite the king’s death, the new ‘commonwealth’ remained vulnerable. In 1649 Cromwell led his troops to victory over pro-Stuart Catholics in Ireland, but not without earning an enduring reputation for unnecessary ferocity. In 1650, he defeated Scottish rebels. Most significantly, he vanquished the combined Scottish-English Royalists supporting Prince Charles’s attempt to claim his father’s throne, at the Battle of Worcester in 1651.

In the absence of traditional hierarchies of church and state, it now fell to Cromwell to impose order but also to balance the interests of a fragmenting country. The position of Parliament remained difficult. Ostensibly, the civil wars had been fought to protect the rights of Parliament. But Parliament itself was beset by disagreements, and the emergence of the New Model Army as the most powerful entity in the land complicated matters. Already, in December 1649, soldiers under Colonel Pride had purged the Long Parliament (sitting since 1640) of members not deemed radical enough, leaving a Rump Parliament of about 60 members more conducive to the army’s agenda. But tensions remained, and in 1653 Cromwell’s patience gave way in spectacular style.

On 20 April, Cromwell attended Westminster Hall as members of the Rump Parliament commenced a third reading of bill about rights for particular categories of electors, contravening an agreement with the army that this would not happen. His patience snapped, as he harangued the ‘factious’ members as ‘a pack of mercenary wretches’ and ‘sordid prostitutes’, who, in his view, had grown ‘intolerably odious to the whole nation’. Summoning soldiers to remove the mace (the ‘shining bauble’) from the chamber – the symbol of Parliament’s authority – Cromwell concluded his lambasting by ordering the MPs: ‘In the name of God, go!’ It was a phrase that would echo down the ages. It was used again, devastatingly, against Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain in May 1940 just before his resignation.

A new Parliament, the so-called Barebones Parliament of 140 appointees, was called but soon dismissed. Cromwell’s chief instrument of authority became his council of state, and later he accepted the title of ‘lord protector’, a quasi-royal status. The Cromwellian years remained paradoxical, for although the methods of governing were experimental and often authoritarian, the reforms and goals were sometimes relatively liberal, for example in readmitting Jews into the country and striving for religious toleration. But the centre could not hold in the absence of its figurehead. When Cromwell died in 1657, his designated successor – his son Richard – failed to exert authority. In 1660 it was another military commander, General Monk, who engineered the return of the monarchy in the shape of Charles II.

IT IS HIGH TIME FOR ME to put an end to your sitting in this place, which you have dishonoured by your contempt of all virtue, and defiled by your practice of every vice; ye are a factious crew, and enemies to all good government; ye are a pack of mercenary wretches, and would like Esau sell your country for a mess of potage, and like Judas betray your God for a few pieces of money; is there a single virtue now remaining amongst you? Is there one vice you do not possess? Ye have no more religion than my horse; gold is your God; which of you have not barter’d your conscience for bribes? Is there a man amongst you that has the least care for the good of the Commonwealth? Ye sordid prostitutes have you not defil’d this sacred place, and turn’d the Lord’s temple into a den of thieves, by your immoral principles and wicked practices? Ye are grown intolerably odious to the whole nation; you were deputed here by the people to get grievances redress’d, are yourselves become the greatest grievance. Your country therefore calls upon me to cleanse this Augean stable,* by putting a final period to your iniquitous proceedings in this House; and which by God’s help, and the strength he has given me, I am now come to do; I command ye therefore, upon the peril of your lives, to depart immediately out of this place; go, get you out! Make haste! Ye venal slaves be gone! Go! Take away that shining bauble there, and lock up the doors. In the name of God, go!

*In Greek mythology, cleaning out the stables of King Augeas of Elis was Hercules’ sixth labour.