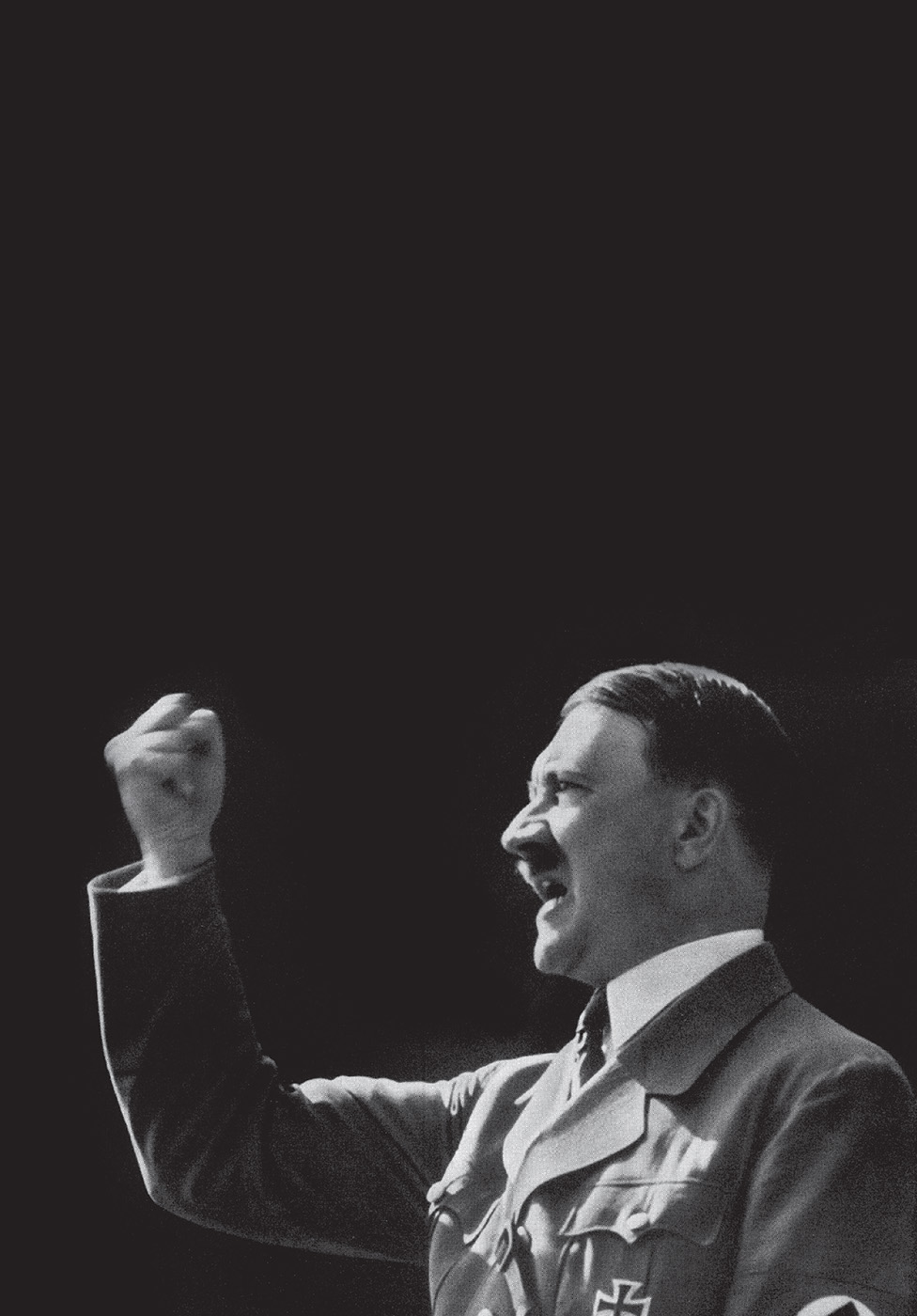

Speech demanding the Sudetenland from Czechoslovakia, 26 September 1938

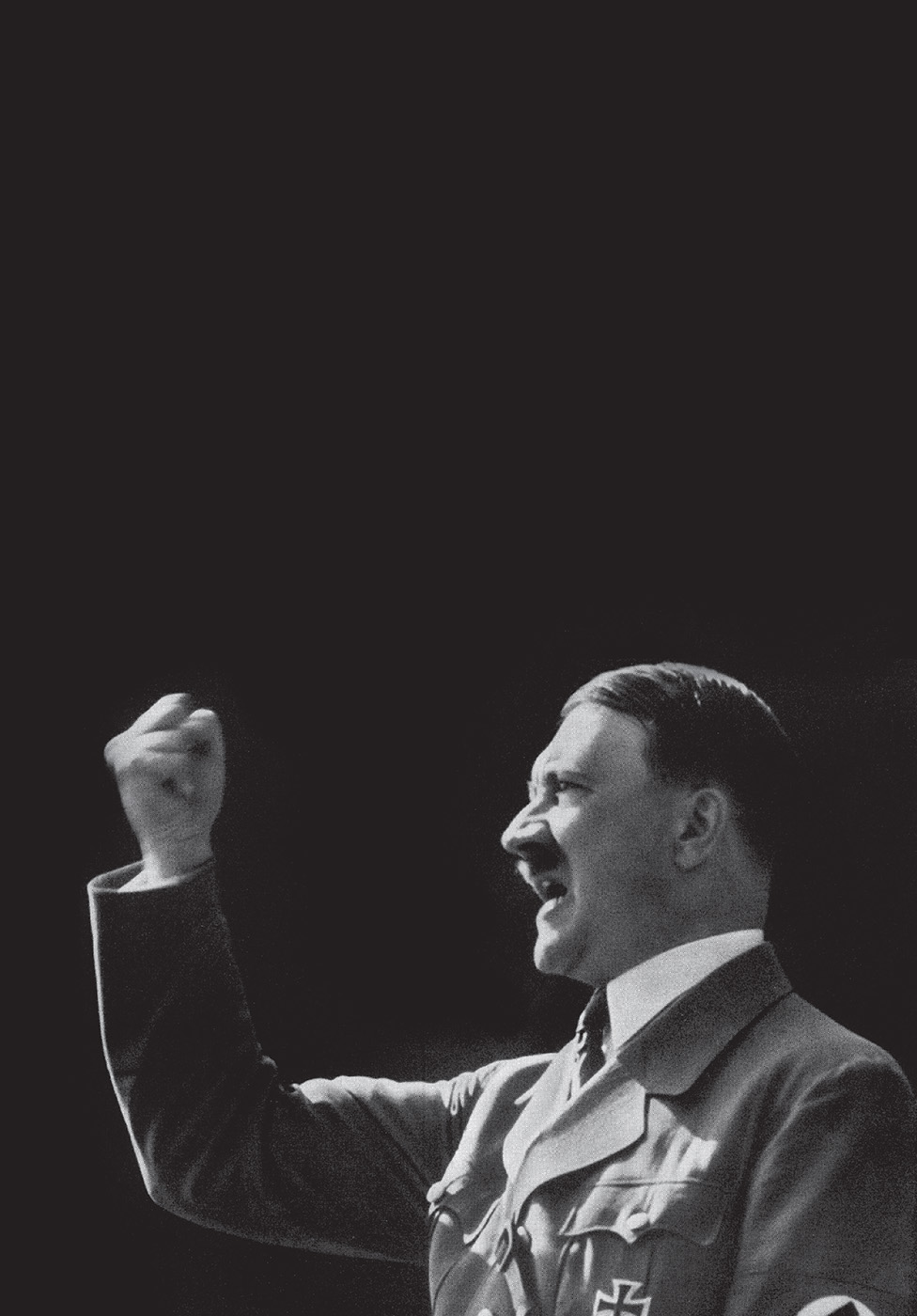

Speech announcing war with Poland, 1 September 1939

ADOLF HITLER

ADOLF HITLER

Born 20 April 1889 in Braunau, Austria. His artistic ambitions were limited by his failure to gain a place at the Vienna Academy.

He combined casual work with occasional sales of his watercolours and postcards, 1909–13. In 1914 he joined a Bavarian regiment on the Western Front: acted as runner, rose to rank of corporal and was wounded, earning the Iron Cross for bravery. In 1920 he joined the tiny National Socialist German Workers Party (abbreviated to Nazi Party), and was soon leading it. An unsuccessful coup in Munich (1923), against the Bavarian state government, landed him in prison for nine months, where he dictated his political and racial philosophy in Mein Kampf (My Struggle). In elections of 1930, the Nazis emerged as the second largest party in Germany’s Weimar Republic. Hitler became chancellor in 1933, initially leading a coalition. Within a year, the parliament building (the Reichstag) was burned down, opposition parties silenced, and the Enabling Acts gave Hitler absolute control. He took the presidency too, on the death of President Hindenburg in 1934, creating the personality cult of the Führer (leader). The years 1935–8 saw German rearmament, the (illegal) remilitarization of the Rhineland, and the annexation of Austria and the Sudetenland. In September 1939, the German invasion of Poland triggered the Franco-British declarations of war, initiating the Second World War. Hitler’s wartime leadership exhibited increasing distrust of his generals and overconfidence in his own instincts; and Nazi-occupied zones and client regimes perpetrated atrocities on a massive scale, notably the attempted genocide of European Jews in the Holocaust. With Germany facing defeat, Hitler narrowly survived assassination by German officers (July 1944). The Führer was reduced to commanding his shattered armies and people from the chancellory bunker in Berlin.

He married his long-term mistress Eva Braun before they committed suicide on the same day, 30 April 1945.

In the early 1930s, among the issues propelling Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party to power in Germany was a widespread resentment at the conditions imposed after the First World War. By the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, the Germany that had existed before 1918 found itself divided in two. The newly independent but landlocked Poland received the so-called ‘Polish Corridor’ of former German land, giving Poland a route to the North Sea. However, that meant that Germany’s easternmost territory – East Prussia – was now disconnected from the rest of Germany.

For Hitler, such territorial loss was both a symbol of German humiliation and a denial of Germany’s true greatness. Having rapidly ‘Nazified’ Germany itself after 1933, imposing party control over the nation’s institutions and dispensing with democracy, Hitler and his entourage turned to the larger project of delivering to the German Volk (people) their rightful due in terms of Lebensraum – the innocuous-sounding ‘living space’.

Hitler worked by diplomatic duplicity, brinksmanship and raising the stakes. The German Volk did not just mean citizens of the German state – Hitler’s term had a much larger sense, implying all those people who might be regarded as culturally, ethnically and linguistically German – and this gave Hitler and the Nazi regime pretexts for their demands and actions. On 12 March 1938, after considerable pressure on the Austrian government, German troops crossed the Austro-German border, and the next day Hitler declared the Anschluss (annexation) of the country. It was, though, a move widely welcomed among Austrians, and to which other powers acquiesced.

For now, the situation with Poland was, at least superficially, stabilized through a Polish–German non-aggression pact of 1934. Quite different, though, was the situation of Czechoslovakia and its ‘Sudeten Germans’ – the German minority in the northwest of the country, who comprised almost a quarter of its population. Czechoslovakia had emerged as an independent republic from the ruins of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1918, and Hitler made plain his contempt for the country’s ‘illegal’ existence, and its leader Edvard Bene (1884–1948), in his speech at the Berlin Sportpalast on 26 September 1938. Having whipped up the grievances of the Sudetenland’s Germans, Hitler used the speech for some unabashed sabre-rattling. His declaration that ‘my patience is now at an end’ could mean nothing less than the threat of war.

(1884–1948), in his speech at the Berlin Sportpalast on 26 September 1938. Having whipped up the grievances of the Sudetenland’s Germans, Hitler used the speech for some unabashed sabre-rattling. His declaration that ‘my patience is now at an end’ could mean nothing less than the threat of war.

The British had already informed Bene that they would not guarantee Czech security – indeed, France and Britain urged him to accommodate Hitler. By 30 September Hitler had got his way, as Italy, Britain and France gave the green light in the Munich Agreement for German absorption of the Sudetenland. (The Czech government was presented with a fait accompli, and had to evacuate the area.) For Britain and France, it was supposed to be an honourable price for a wider European peace. For Hitler, it proved another cost-free success.

that they would not guarantee Czech security – indeed, France and Britain urged him to accommodate Hitler. By 30 September Hitler had got his way, as Italy, Britain and France gave the green light in the Munich Agreement for German absorption of the Sudetenland. (The Czech government was presented with a fait accompli, and had to evacuate the area.) For Britain and France, it was supposed to be an honourable price for a wider European peace. For Hitler, it proved another cost-free success.

. . . I HAVE REALLY IN THESE YEARS pursued a practical peace policy. I have approached all apparently impossible problems with the firm resolve to solve them peacefully even when there was the danger of making more or less serious renunciations on Germany’s part. I myself am a front-line soldier and I know how grave a thing war is. I wanted to spare the German people such an evil. Problem after problem I have tackled with the set purpose to make every effort to render possible a peaceful solution.

The most difficult problem which faced me was the relation between Germany and Poland. There was a danger that the conception of a ‘heredity enmity’ might take possession of our people and of the Polish people. That I wanted to prevent. I know quite well that I should not have succeeded if Poland at that time had had a democratic constitution. For these democracies which are overflowing with phrases about peace are the most bloodthirsty instigators of war. But Poland at that time was governed by no democracy but by a man [General Pilsudski, who staged a military coup in 1926]. In the course of barely a year it was possible to conclude an agreement which, in the first instance for a period of ten years, on principle removed the danger of a conflict. We are all convinced that this agreement will bring with it a permanent pacification. We realize that here are two peoples which must live side by side and that neither of them can destroy the other. A state with a population of thirty-three millions will always strive for an access to the sea. A way to an understanding had therefore to be found.

. . . And now before us stands the last problem that must be solved and will be solved. It is the last territorial claim which I have to make in Europe, but it is the claim from which I will not recede and which, God willing, I will make good.

. . . I have only a few statements still to make. I am grateful to Mr Chamberlain for all his efforts. I have assured him that the German people desires nothing else than peace, but I have also told him that I cannot go back behind the limits set to our patience. I have further assured him, and I repeat it here, that when this problem is solved there is for Germany no further territorial problem in Europe. And I have further assured him that at the moment when Czechoslovakia solves her problems, that means when the Czechs have come to terms with their other minorities, and that peaceably and not through oppression, then I have no further interest in the Czech state. And that is guaranteed to him! We want no Czechs!

But in the same way I desire to state before the German people that with regard to the problem of the Sudeten Germans my patience is now at an end! I have made Mr Beneš an offer which is nothing but the carrying into effect of what he himself has promised. The decision now lies in his hands: peace or war. He will either accept this offer and now at last give to the Germans their freedom or we will go and fetch this freedom for ourselves.

By March 1939, Czechoslovakia as an independent republic was no more. Hitler had shown his disregard for the 1938 Munich Agreement by swallowing up the regions of Bohemia and Moravia, while his ally Hungary had taken its own portion of the country, and Slovakia had adopted its own fascist government.

The lesson for Hitler seemed to be that concerted pressure paid off, and in 1939 that pressure was applied to Poland. Germany demanded land access to East Prussia and threatened the neutral status of the disputed Free City of Danzig (now Gdansk, in Poland), where Nazi influence was strong. Additionally, Hitler’s racial theories regarded Slav peoples as ‘sub-human’, so Poland held the prospect of justifiable additional Lebensraum for German expansion. Poland refused to concede, and as with Czechoslovakia Nazi propaganda fuelled patriotic German resentment. In August, the path for action was cleared when Nazi Germany and the communist Soviet Union – bitter ideological foes – concluded a non-aggression pact of convenience, enabling the mutual division of Poland. By 1 September, German Nazis in Danzig were rebelling, and German soldiers had manufactured a counterfeit Polish border clash, giving Hitler the pretexts he needed for full-scale invasion. His speech on that day gave empty reassurance to Britain and France, announced the cynical rapprochement with the Soviet Union, menaced Poland, promised retribution to traitors at home, and demanded ‘every sacrifice’ from the German people.

Historians debate how far Hitler understood the implications of his actions. On the one hand, his vivid phraseology clearly anticipates a life-or-death struggle ahead. However, his foreign minister, Von Ribbentrop, assured him that Britain and France would appease him yet again over Poland, to avoid a wider war. He was wrong, and by 3 September Britain and France had declared war. But it was too late to save Poland.

I HAVE DECLARED THAT THE FRONTIER between France and Germany is a final one. I have repeatedly offered friendship and, if necessary, the closest cooperation to Britain, but this cannot be offered from one side only. It must find response on the other side. Germany has no interests in the west, and our western wall is for all time the frontier of the Reich on the west. Moreover, we have no aims of any kind there for the future. With this assurance we are in solemn earnest, and as long as others do not violate their neutrality we will likewise take every care to respect it.

I am happy particularly to be able to tell you of one event. You know that Russia and Germany are governed by two different doctrines. There was only one question that had to be cleared up. Germany has no intention of exporting its doctrine. Given the fact that Soviet Russia has no intention of exporting its doctrine to Germany, I no longer see any reason why we should still oppose one another. On both sides we are clear on that. Any struggle between our people would only be of advantage to others. We have, therefore, resolved to conclude a pact which rules out for ever any use of violence between us. It imposes the obligation on us to consult together in certain European questions. It makes possible for us economic cooperation, and above all it assures that the powers of both these powerful states are not wasted against one another. Every attempt of the West to bring about any change in this will fail.

At the same time I should like here to declare that this political decision means a tremendous departure for the future, and that it is a final one. Russia and Germany fought against one another in the World War. That shall and will not happen a second time. In Moscow, too, this pact was greeted exactly as you greet it. I can only endorse word for word the speech of the Russian Foreign Commissar, [Vyacheslav] Molotov.

I am determined to solve the Danzig question; the question of the Corridor and to see to it that a change is made in the relationship between Germany and Poland that shall ensure a peaceful co-existence. In this I am resolved to continue to fight until either the present Polish government is willing to bring about this change or until another Polish government is ready to do so. I am resolved to remove from the German frontiers the element of uncertainty, the everlasting atmosphere of conditions resembling civil war. I will see to it that in the East there is, on the frontier, a peace precisely similar to that on our other frontiers.

In this I will take the necessary measures to see that they do not contradict the proposals I have already made known in the Reichstag itself to the rest of the world, that is to say, I will not war against women and children. I have ordered my air force to restrict itself to attacks on military objectives. If, however, the enemy thinks he can from that draw carte blanche on his side to fight by the other methods he will receive an answer that will deprive him of hearing and sight.

This night for the first time Polish regular soldiers fired on our own territory. Since 5.45 a.m. we have been returning the fire, and from now on bombs will be met with bombs. Whoever fights with poison gas will be fought with poison gas. Whoever departs from the rules of humane warfare can only expect that we shall do the same. I will continue this struggle, no matter against whom, until the safety of the Reich and its rights are secured.

For six years now I have been working on the building up of the German defences. Over 90 milliards have in that time been spent on the building up of these defence forces. They are now the best equipped and are above all comparison with what they were in 1914. My trust in them is unshakeable. When I called up these forces and when I now ask sacrifices of the German people and if necessary every sacrifice, then I have a right to do so, for I also am today absolutely ready, just as we were formerly, to make every personal sacrifice.

I am asking of no German man more than I myself was ready throughout four years at any time to do. There will be no hardships for Germans to which I myself will not submit. My whole life henceforth belongs more than ever to my people. I am from now on just first soldier of the German Reich. I have once more put on that coat that was the most sacred and dear to me. I will not take it off again until victory is secured, or I will not survive the outcome.

As a National Socialist and as a German soldier I enter upon this struggle with a stout heart. My whole life has been nothing but one long struggle for my people, for its restoration, and for Germany. There was only one watchword for that struggle: faith in this people. One word I have never learned: that is, surrender.

If, however, anyone thinks that we are facing a hard time, I should ask him to remember that once a Prussian king, with a ridiculously small state, opposed a stronger coalition, and in three wars finally came out successful because that state had that stout heart that we need in these times. I would, therefore, like to assure all the world that a November 1918 will never be repeated in German history. Just as I myself am ready at any time to stake my life – anyone can take it for my people and for Germany – so I ask the same of all others.

Whoever, however, thinks he can oppose this national command, whether directly or indirectly, shall fall. We have nothing to do with traitors. We are all faithful to our old principle. It is quite unimportant whether we ourselves live, but it is essential that our people shall live, that Germany shall live. The sacrifice that is demanded of us is not greater than the sacrifice that many generations have made. If we form a community closely bound together by vows, ready for anything, resolved never to surrender, then our will will master every hardship and difficulty. And I would like to close with the declaration that I once made when I began the struggle for power in the Reich. I then said: ‘If our will is so strong that no hardship and suffering can subdue it, then our will and our German might shall prevail.’