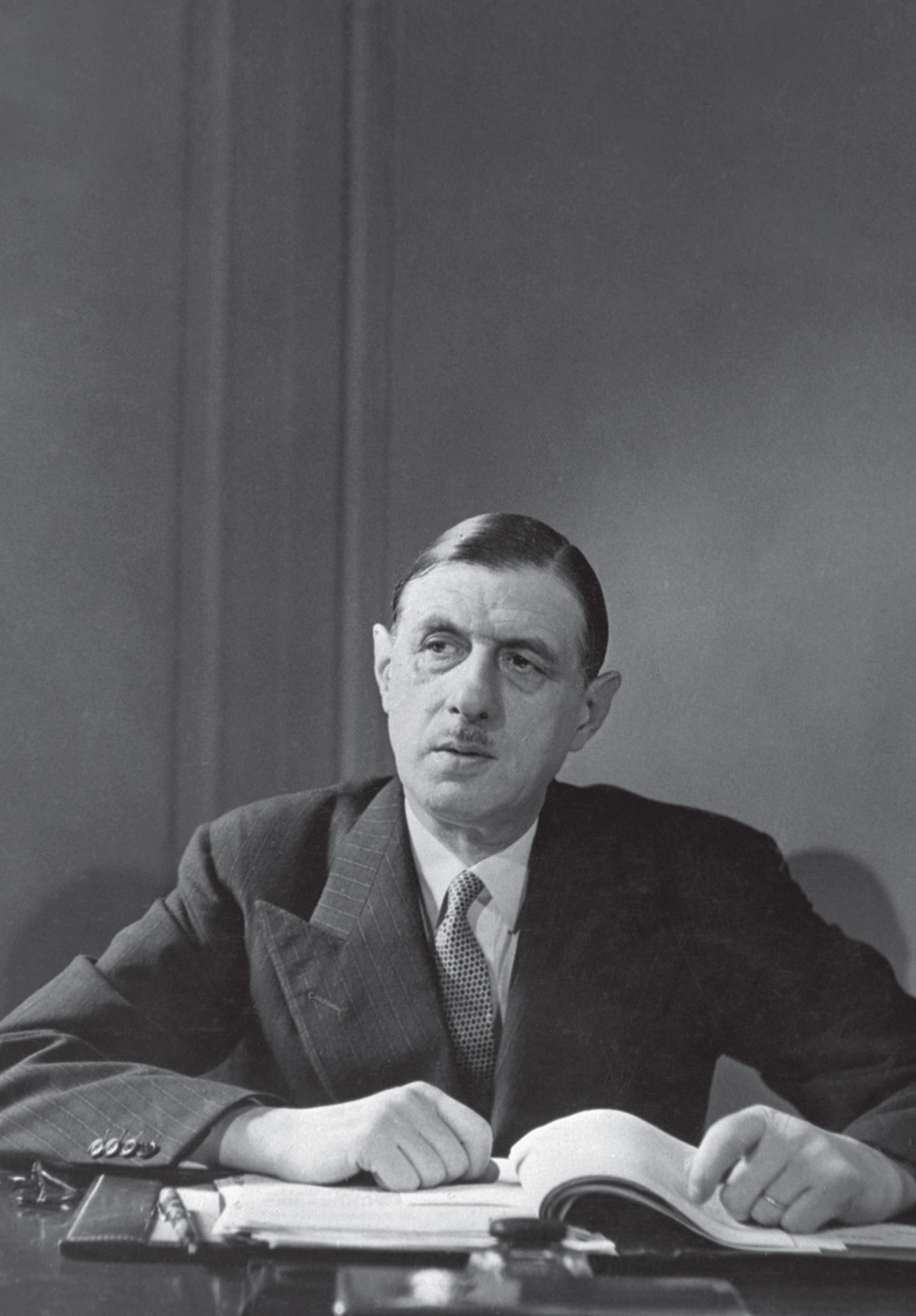

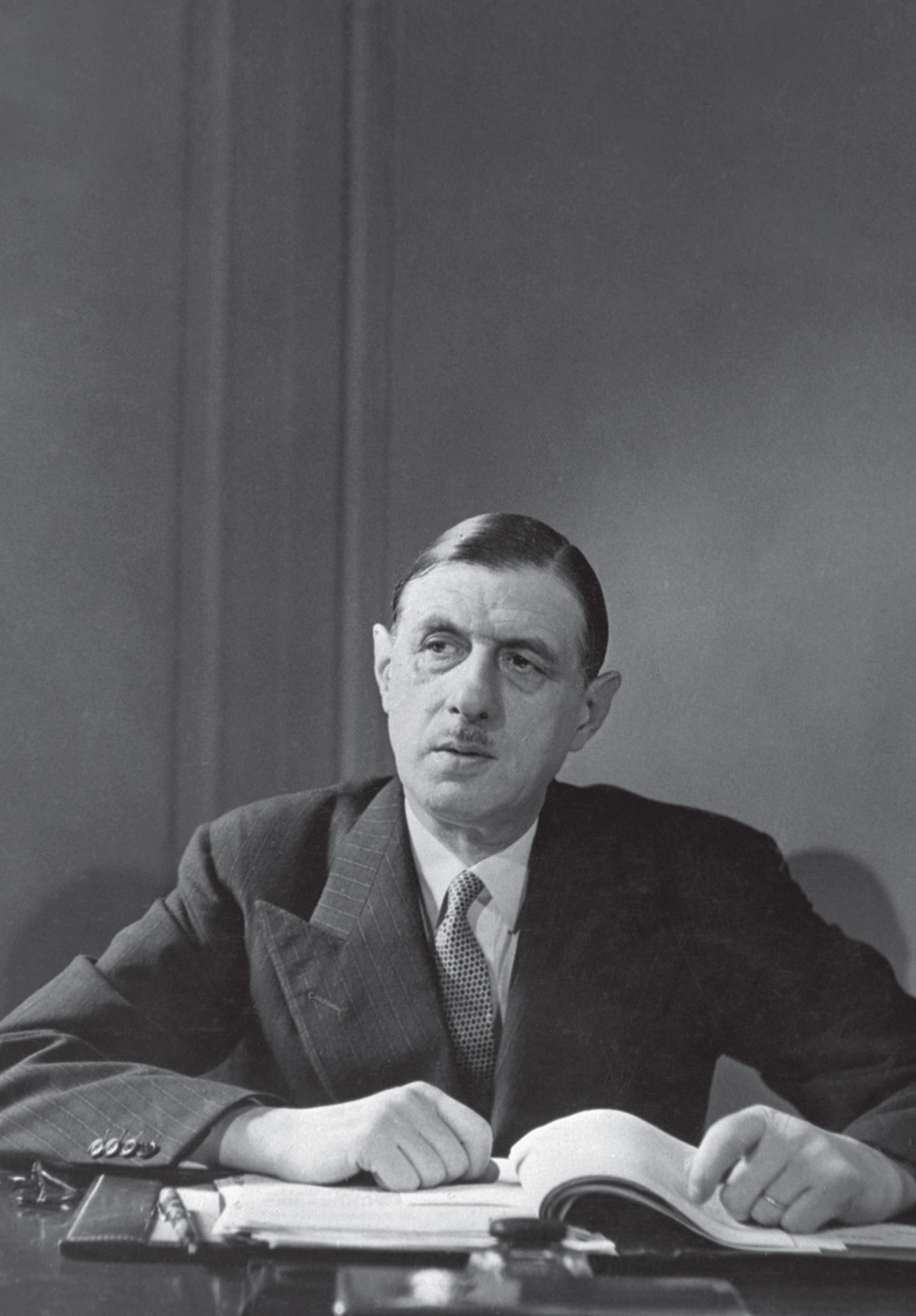

CHARLES DE GAULLE

Radio appeal to create the Free French forces, 18 June 1940

CHARLES DE GAULLE

Born 22 November 1890 in Lille, France. A career soldier, he graduated from the Military Academy St Cyr in 1912 and joined an infantry regiment.

He served as a lieutenant in the First World War, during which he was wounded several times and captured at Verdun. He served in Poland as a major and military adviser during the Russo-Polish War (1919–21), and then studied and lectured at war college. His book The Army of the Future (1934), advocating a mechanization of the infantry and the widespread use of tanks, made him unpopular with the military establishment. His talents belatedly recognized, he was promoted to general and hoisted into the French government as France fell to Nazi Germany, in June 1940. He fled to England and appealed for the French to continue fighting. By 1944 de Gaulle had gained supreme control of the French war effort outside France and was increasingly recognized as the legitimate leader of a French government in exile. During 1944–6, he led provisional French governments but resigned over new constitutional arrangements. When France faced a crisis over war in Algeria (1958), he became prime minister and later that year, after constitutional changes, the first President of the Fifth Republic. He pursued a nationalistic foreign policy, making France a nuclear power and stressing independence from Britain and the United States while developing close relations with West Germany. After what he took to be a no-confidence vote in him, following a referendum, he resigned in 1969.

He survived a number of assassination plots, and died 9 November 1970 in Colombey-les-Deux-Eglises, France.

The rapid collapse of the French military in June 1940, in the face of the Nazi offensive, sent shock and panic throughout France. Winston Churchill pressed the French to continue fighting, and even proposed a formal union of the two countries, but it was grabbing at straws. On 14 June German soldiers entered Paris, which was undefended, and on 16 June the French Prime Minister Paul Reynaud resigned, to be replaced by a hero from a previous war – Marshal Philippe Pétain. His new government immediately set about negotiating surrender.

Despite the generally lacklustre performance of the French army, one commander of a tank division had distinguished himself: General Charles de Gaulle. In early May he was a colonel whose opinionated stance on the necessity for mechanized-warfare tactics (as the German used) had stunted his career path. But sudden, rapid promotion took him into the French Cabinet in early June as under-secretary of defence. Refusing to accept the defeatism of Pétain, he escaped to Britain, where thousands of French troops had landed after evacuation from Dunkirk in early June. With Churchill’s backing, he set himself up as an alternative French leader to Pétain. On 18 June, the same day as Churchill proclaimed the approach of the ‘Battle of Britain’, de Gaulle made a broadcast to rally those French men and women in a position to continue the fight. Perhaps the most famous phrase associated with his appeal – ‘France has lost a battle. But France has not lost the war!’ – was never actually broadcast.

Marshal Pétain became head of the technically neutral (but increasingly collaborationist) Vichy French regime, in the south of France, an ignoble role that resulted in his standing trial for treason after the war. By contrast, de Gaulle became a symbol of French defiance and worked hard to persuade the British, the Americans and French Resistance groups to accept him as the head of the Free French forces. The prickly de Gaulle had a difficult relationship with Churchill, and an even more problematic one with US President Roosevelt, and he often felt (and was) sidelined by the Anglo-American axis. Nevertheless, in the end it was General de Gaulle who entered a liberated Paris in triumph on 26 August 1944, and who went on to become the country’s president in 1958.

THE LEADERS WHO, FOR MANY YEARS PAST, have been at the head of the French armed forces, have set up a government. Alleging the defeat of our armies, this government has entered into negotiations with the enemy with a view to bringing about a cessation of hostilities. It is quite true that we were, and still are, overwhelmed by enemy mechanized forces, both on the ground and in the air. It was the tanks, the planes and the tactics of the Germans, far more than the fact that we were outnumbered, that forced our armies to retreat. It was the German tanks, planes and tactics that provided the element of surprise which brought our leaders to their present plight.

But has the last word been said? Must we abandon all hope? Is our defeat final and irremediable? To these questions I answer – No!

Speaking in full knowledge of the facts, I ask you to believe me when I say that the cause of France is not lost. The very factors that brought about our defeat may one day lead us to victory. For, remember this, France does not stand alone. She is not isolated. Behind her is a vast empire, and she can make common cause with the British Empire, which commands the seas and is continuing the struggle. Like England, she can draw unreservedly on the immense industrial resources of the United States.

This war is not limited to our unfortunate country. The outcome of the struggle has not been decided by the Battle of France. This is a world war. Mistakes have been made, there have been delays and untold suffering, but the fact remains that there still exists in the world everything we need to crush our enemies some day. Today we are crushed by the sheer weight of mechanized force hurled against us, but we can still look to a future in which even greater mechanized force will bring us victory. The destiny of the world is at stake.

I, General de Gaulle, now in London, call on all French officers and men who are at present on British soil, or may be in the future, with or without their arms. I call on all engineers and skilled workmen from the armaments factories who are at present on British soil, or may be in the future, to get in touch with me.

Whatever happens, the flame of French resistance must not and shall not die.