11

Commas

This chapter covers the varied uses of commas—and the errors associated with this punctuation mark. In fact, commas seem to account for a huge proportion of most people’s questions and concerns regarding correct grammar, punctuation, and usage.

1. Commas with and, but, and or (and other coordinating conjunctions): A coordinating conjunction is a word used to connect other words. The most common coordinating conjunctions are and, but, and or.

A coordinating conjunction can combine various words and groups of words. One of the most common problems involves using a comma right before a coordinating conjunction in what is—or what only appears to be—a compound sentence. A compound sentence is a single sentence that is composed of what could be two separate sentences. Here is an example that is correctly punctuated, with the coordinating conjunction underlined:

I want to read the classics, but I have a short attention span.

In this section, we discuss two related problems. The first involves failing to put a comma before the coordinating conjunction in a compound sentence. The second involves mistakenly putting a comma before a coordinating conjunction because the sentence appears to be (but is not) a compound sentence. We also provide one tip for avoiding both errors.

2. Commas with introductory elements: An introductory element is a general term used to refer to a word or group of words placed at the front of the sentence—before the subject and verb. Following are two examples:

According to some sources, Benjamin Franklin roasted a turkey on a rotating electric spit in 1749.

In the 1950s, a Texas town named Lolita almost changed its name to avoid being associated with a controversial novel with the same name.

People often have strong preferences as to whether some introductory elements can, must, or must not have a comma afterward. Most general handbooks indicate a comma should be used, but some professions and organizations indicate otherwise.

As we discuss in this section, certain types of introductory elements are less debatable in terms of punctuation. We also explain why we suggest putting a comma after every type of introductory element, unless the writer knows the readers expect otherwise.

3. Commas with adjective clauses: An adjective clause is a group of words that together describe a person, place, or thing. Adjective clauses often begin with who, whom, whose, which, or that. Sometimes an adjective clause is separated from the rest of a sentence by a comma. At other times, it would be an error to set off the clause with commas. Following are correct examples (adjective clauses underlined):

Outdoor scenes in the movie Oklahoma, which was a huge hit in 1955, were actually filmed in Arizona.

I know a mechanic who can help you.

The decision regarding using a comma is a complex one. As we describe in this section, the matter rests on whether the word being described by the adjective clause is sufficiently clear and specific without the clause. If so, the clause is nonessential, and commas are required, as seen in the example about the movie Oklahoma.

4. Commas with adverb clauses: An adverb clause is a group of words that act together. As its name suggests, the adverb clause functions as an adverb. In this section, we focus on commas used when the adverb clause functions to modify a verb.

Some adverb clauses must have commas separating them from the rest of a sentence. With other adverb clauses, there should not be any such commas. And still in other situations, using commas is optional. Following are examples of correctly punctuated adverb clauses (underlined):

While I was in England visiting friends, I was told that the game of darts started in the Middle Ages as a way to train archers.

The numbering system on a dartboard is a bit of a mystery because nobody knows its origins.

This section discusses the rules that most grammar experts agree on in terms of punctuating adverb clauses. This section also offers suggestions on how to deal with some of the situations when there is not such widespread agreement.

5. Commas with appositives: An appositive is a word (or group of words) with no other function except to rename a previous noun or pronoun. Contrary to what many people assume, appositives are not necessarily set off with commas. If an appositive is not really necessary, it is set off with commas, but appositives that readers need in order to understand the sentence are not set off with commas.

Here are two examples of appositives (underlined), the first of which requires commas because the appositive is not necessary:

A month before being shot in his car by law officers, Clyde Barrow, a notorious criminal, wrote a letter to Henry Ford praising him for the “dandy” automobile he made.

In 1885 the Apache chief Geronimo was outnumbered by 150 to 1 yet managed to hold off the U.S. Army for half a year.

In this section, we discuss when you should and should not use commas with appositives.

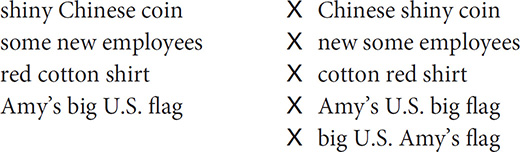

6. Commas with adjectives: Adjectives are words that modify nouns, and it is common for writers to have two or more adjectives in a row before the noun they modify. Some people mistakenly assume all such adjectives are separated by commas from one another. Sometimes commas are required, but sometimes not, as seen here (adjectives underlined):

We bought a large, expensive computer.

Terrie is wearing a red cotton skirt.

Commas are needed when adjectives are “coordinate”—when they belong to the same basic class of adjectives. When the adjectives belong to different classes, commas should not be used. This matter might seem confusing because few people are aware of the different categories of adjectives. We offer two commonsense tips for helping people see the distinctions and punctuate adjectives correctly.

Commas with and, but, and or (and Other Coordinating Conjunctions)

A coordinating conjunction is a word used to combine words, phrases, or entire sentences. When combining sentences, use a comma immediately before the coordinating conjunction. Coordinating conjunctions are words that have little meaning by themselves; their primary purpose is to connect other words that do have important meaning. In this section, we focus on coordinating conjunctions used to combine entire sentences. To a lesser extent, this section covers guidelines for combining verbs that share the same subject.

The most common coordinating conjunctions are and, but, and or. As noted earlier, a good way to remember all the coordinating conjunctions is using the acronym FANBOYS:

For

And

Nor

But

Or

Yet

So

These three sentences correctly use a comma along with a coordinating conjunction (underlined) to combine sentences:

Guion Bluford was the first African American to fly in space, and he was a decorated Air Force veteran.

I asked for cream in my coffee, but the waiter did not give me any.

You can submit the report on time, or we can all work until midnight to get the work done.

Commas have many functions, and many errors occur simply because people cannot keep up with the varied ways in which a comma should be used—or not used. One of the most common uses (and misuses) is when a comma is used to combine entire sentences. Actually, there are two types of errors connected with this use of a comma. Although both types are relatively common, neither is particularly serious in the eyes of most readers—certainly not as serious or annoying as a fragment or a comma splice. In fact, neither type of error has a name that people agree on (which is why the title of this section is unusually long). Before considering these two types of errors, remember the following rule to avoid the problem altogether:

Think of it this way: the comma in this situation is like a weak period. The comma is taking the place of what could be a period, as shown here:

Somebody ordered ten filing cabinets, but they have not arrived.

or

Somebody ordered ten filing cabinets. But they have not arrived.

Many readers regard starting a sentence with but or another coordinating conjunction to be too informal. However, technically you can do so. The important point is that you should combine two sentences by using a comma plus a coordinating conjunction.

Let’s discuss the first type of error connected with this sort of sentence. A common mistake people make is that they leave out the comma, as illustrated in these two incorrect sentences:

X We will reimburse you for expenses but you should be careful about how much you spend.

X Ants might not seem very intelligent yet their brains are larger than those of most other insects their size.

The problem is that the comma is supposed to be a subtle clue. It indicates that what comes afterward is an idea that, even if related to the first part of the sentence, is going in a new direction. Grammatically speaking, the comma prepares readers for a new subject and a new verb. This creates a compound sentence—a sentence composed of what could be two sentences (see Chapter 6). Another way of putting it is that a compound sentence is made of at least two independent clauses. By far, the most common means of connecting the two parts of a compound sentence is a comma, although using a semicolon is another option (see Chapter 13).

Applying the rule easily corrects these problems. Place a comma where you could place a period (immediately before the coordinating conjunction):

We will reimburse you for expenses, but you should be careful about how much you spend.

Ants might not seem very intelligent, yet their brains are larger than those of most other insects their size.

There is a second type of error connected with a coordinating conjunction and what appears to be a compound sentence: some people mistakenly use a comma before a coordinating conjunction. That is, sometimes a person will take the aforementioned rule too far and unnecessarily use a comma, as in these two examples:

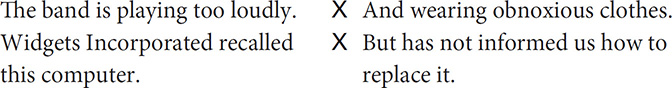

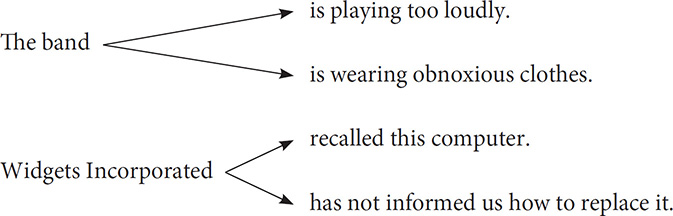

X The band is playing too loudly, and wearing obnoxious clothes.

X Widgets Incorporated recalled this computer, but has not informed us how to replace it.

What comes after each comma cannot stand on its own as a complete sentence. Put another way, you cannot replace these two commas with periods:

Because the second halves cannot stand alone, the original sentences were not true compound sentences. Thus, a comma is not needed before the conjunction.

Again, consider the rule: Use a comma before a coordinating conjunction used to combine what could be two sentences. This rule also means that you should not use a comma when what comes afterward relies on the first part of the sentence. Grammatically speaking, these last two sentences are not compound sentences. Rather, they involve compound verbs. In each sentence, the subject is doing two actions:

In each of these examples, putting a comma between the two actions interrupts the way in which the two verbs go back to a single subject. To fix the problem, leave out the commas:

The band is playing too loudly and is wearing obnoxious clothes.

Widgets Incorporated recalled this computer but has not informed us how to replace it.

As noted earlier, neither of these errors (leaving out the comma or putting it in needlessly) is considered to be very serious by most readers. In fact, this is one of those gray areas of punctuation. Many grammar handbooks state that you have the option of omitting the comma in a compound sentence if the first part of the sentence is fewer than five words, as in I drove home but nobody was there. Also, some people—especially if they are trying to be emphatic or simulate the way people pause when speaking—will use a comma to separate two verbs, as in I want you to leave, and never return. These are the exceptions, and the prudent approach is to not break the rules lightly.

Summary

To figure out if you need a comma before a coordinating conjunction (such as and, but, or or), you should determine if what comes after the coordinating conjunction could potentially be a complete sentence. If yes, the comma is needed before the conjunction. If no, no comma is needed before the conjunction.

Commas with Introductory Elements

Sentences normally begin with a subject followed by a verb. An introductory element refers to other types of words that are not part of the subject but are still placed at the beginning of a sentence, as shown in these two examples (introductory elements underlined):

When I was sixteen, my father gave me a sailboat.

However, the boat sank after I had it only a week.

A comma is useful because it is a marker indicating where the “real” sentence begins—with the subject and its verb. In fact, a handy way to detect an introductory element is to see if it can be moved around so that the sentence can begin another way.

Applying this tip reveals that the two examples just given indeed have introductory elements:

My father gave me a sailboat when I was sixteen.

The boat, however, sank after I had it only a week.

As you can see, commas might or might not be needed if you move an introductory element to some other place in a sentence, but this issue is not important because you are just toying with the original sentence. The point is that you can move when I was sixteen and however around, indicating that indeed they are introductory elements.

What’s the Problem?

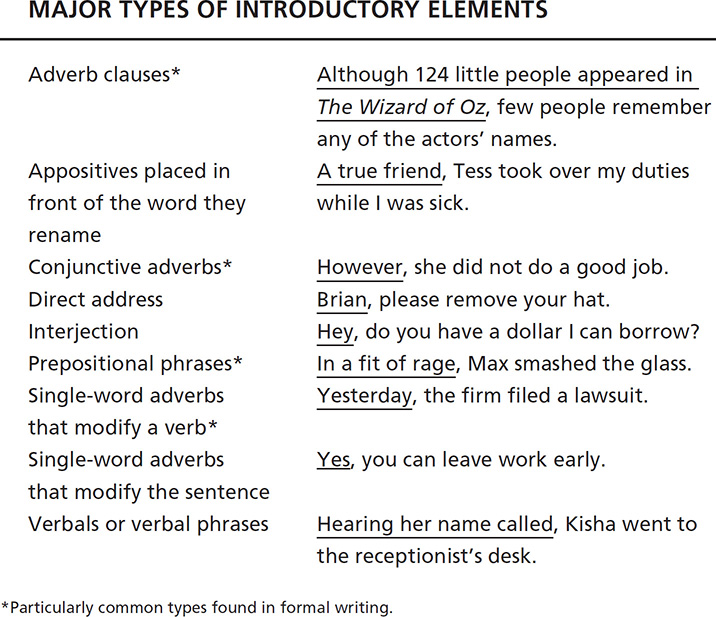

The problem is that writers must decide if a comma is needed after an introductory element once they know a sentence has such an introductory element. The bigger problem, though, is that not all readers or grammar handbooks are in agreement about using a comma after an introductory element, largely because the term introductory element is a catchall term that covers several types of structures. See the table that follows for additional information, though it is not necessary to remember all of these structures. (Introductory elements are underlined.)

Almost every handbook agrees that some types of elements (such as direct address) must have commas. Most handbooks also agree that there are times when the comma is optional, especially if the element is short (as with short prepositional phrases). However, there are different definitions about what is short or long (most handbooks define a long introductory element as one that is five words or more). To compound the problem, there are certain readers, businesses, or professions that—no matter what the handbooks or English teachers say—have strong preferences about requiring or banning the use of commas after introductory elements.

Most handbooks that—like this one—are written for people in diverse situations state that commas are required for certain types of introductory elements. These handbooks also indicate there are some instances when commas are optional. However, almost no general-use handbook states that it is wrong to put a comma after an introductory element. Thus, the safe approach seems to be that, if in doubt, you should use a comma after an introductory element because doing so is almost never wrong according to the great majority of grammar handbooks aimed at a general audience.

Keep in mind, though, the following exceptions to our suggestion of using a comma after all introductory elements:

• One informal type of introductory element is the coordinating conjunction (see Chapter 1) and normally a comma should not be used in this situation, as shown here (coordinating conjunctions underlined):

Paulette was asked to call us immediately. But she must have decided otherwise.

You can leave now. Or we will have to call the authorities.

• In certain professions (such as journalism), commas are usually left out after introductory elements, unless doing so would clearly make the sentence difficult to understand.

• Although preferences in this matter are difficult to measure, there seems to be an increasing number of organizations and businesses that prefer commas to be omitted after short introductory elements. In time, the safe approach we have described might not be so safe!

Other Areas of Agreement

Again, it is unlikely that you would break a widely accepted rule if you put a comma after every introductory element. Here are other guidelines that are widely accepted:

1. You must use a comma if leaving it out could cause serious misreading of a sentence. If you leave out the comma, there are times when the reader cannot tell if a word is the last part of the introductory element or if it is the subject of the whole sentence:

X When eating the cat purrs loudly.

X While Ann was bathing the telephone rang.

In the first sentence, you might think somebody ate the cat, and in the second, it might seem that Ann gave her phone a bath. Although both of the elements are short, commas are needed to prevent misreading:

When eating, the cat purrs loudly.

While Ann was bathing, the telephone rang.

2. Even people who prefer that commas be used sparingly tend to agree that long introductory elements require commas. As noted earlier, there is no standard definition of what is long, but clearly sentences such as the following need a comma to let readers know where the main part of the sentence begins:

Although Mark Twain wrote several lengthy novels during his distinguished career, he was granted a patent for a book that contained no words at all (entitled Self-Pasting Scrapbook).

Having been taught to use a comma after most introductory elements in a sentence, Jerome rarely had to consult a grammar book on the issue.

Summary

When deciding if you should use a comma after an introductory element, consider the following:

• An introductory element can be easily recognized because they can almost always be moved to another position in the sentence.

• Most grammar handbooks written for general purposes state that it is never wrong to use a comma after an introductory element. Nonetheless, some people assume otherwise, so it is wise to determine the preferences of your readers, business, or organization.

• If in doubt, use commas after introductory elements of all types.

• Definitely use a comma when it is needed to prevent confusion or when the element is long (five words or more).

• It is optional to use a comma after short introductory clauses and prepositional phrases, but again it is simpler and more consistent to use commas after every introductory element.

Commas with Adjective Clauses

An adjective clause is a group of words used together to describe a person, place, or thing. Adjective clauses often begin with who, whom, whose, which, or that. As seen in the fourth example that follows, sometimes these words can be deleted, though they are understood to be there.

We need a photocopier that will not break down twice a week.

Edwin Booth, who was the brother of the man who shot Abraham Lincoln, once saved one of Lincoln’s sons from being run over by a train.

I saw a woman whom I once dated.

I saw a woman I once dated.

In each of the four sentences above, the underlined clause describes a noun (a photocopier, Edwin Booth, or a woman). Thus, each clause is a single unit that functions as an adjective. (Adjective clauses are sometimes called relative clauses; the two terms mean exactly the same thing.)

What’s the Problem?

As illustrated in the preceding examples, some adjective clauses are separated from the rest of a sentence with commas, while others are not. This is a complicated issue because it rests on the specific nature of each sentence and what the writer assumes is essential in order for readers to understand the sentence. The punctuation decision seems particularly subjective because ultimately it comes down to what the writer and reader consider to be essential information.

Using Commas with Adjective Clauses

Normally, the punctuation decision is not difficult if you keep the preceding tip in mind. Just look at the noun or pronoun being described by the clause. (This noun or pronoun will usually appear immediately before the adjective clause.) If this noun or pronoun has already been made specific for readers, then the clause is merely giving a little additional information. Adjective clauses are underlined in the following:

My mother, who lives in Seattle, calls me every day.

I drove to Ralph’s Hardware Store, which is open on Sundays.

In the first sentence, the word mother is already made specific because of the adjective my, so you do not need the underlined clause. You know whose mother is involved, and the fact that she lives in Seattle is some additional tidbit. If we can assume that there is only one Ralph’s Hardware Store, then similarly the adjective clause in the second example is not needed in order to know which store the writer has in mind. In short, a nonessential adjective clause is set off from the “meat” of the sentence. It is nonessential if the reader does not need it to determine which person, place, or thing the writer has in mind.

An error would occur if commas were not used to set off a nonessential adjective clause, as in this example:

X Dr. Dolittle who has been my physician for years has asked me not to come back.

The clause modifies a term (Dr. Dolittle) that is already specific and clear. Such an error can be easily corrected by inserting commas:

Dr. Dolittle, who has been my physician for years, has asked me not to come back.

This example, noted already, might seem more difficult to punctuate:

Edwin Booth, who was the brother of the man who shot Abraham Lincoln, once saved one of Lincoln’s sons from being run over by a train.

The adjective clause is describing Edwin Booth and does include important information in the sense that most people do not know who Edwin Booth is. Even though the clause seems vital, the noun Edwin Booth is still so specific that the adjective clause is not essential. An adjective clause might contain important facts or details, but the key is usually whether the noun or pronoun is already specific. Such is the case with this sentence, so the writer must use commas.

Adjective Clauses That Do Not Need Commas

As stated earlier, do not use a comma when the clause is essential for helping readers identify the noun or pronoun being described. Again, consider whether the person, place, or thing being modified has already been sufficiently identified. Is the noun or pronoun general enough to require additional identifying information? If so, the adjective clause is too important to separate from the word it describes.

We hired a lawyer whose firm specializes in mass litigation. (Which lawyer?)

I have something that I need to discuss with you. (What something?)

Errors occur when the writer uses commas with adjective clauses that are essential for identifying the noun or pronoun being modified:

X The person, who has borrowed the company van, needs to return the vehicle at once.

The term person is much too vague without the clause. It’s not just any person who must return the vehicle but the one who borrowed it. Use commas to set off adjective clauses only if the word being described is sufficiently specific and clear. As you can see, correcting this error is simple—just leave out the commas:

The person who has borrowed the company van needs to return the vehicle at once.

Sometimes It Just Depends

Every now and then, the word being modified by the adjective clause could be sufficiently specific by itself—or not. The matter depends on the larger situation beyond the sentence.

Consider this sentence:

My son who is a stamp collector is at a convention in Tulsa.

Are commas needed? It depends on how many sons the writer has. If there is only one, the term my son is already specific, for it could only mean one thing. Accordingly, the sentence would need commas to separate the nonessential adjective clause from the rest of the sentence:

My son, who is a stamp collector, is at a convention in Tulsa. (If there is only one son.)

But if the writer has more than one son, then my son is not clear. Thus, the adjective clause is now essential for us to understand which son the writer has in mind. Leave out commas when a clause is this essential:

My son who is a stamp collector is at a convention in Tulsa. (If there are two or more sons.)

The tip discussed earlier tells you whether to use commas or not: use a comma with an adjective clause only if the clause is not essential for identifying the person, place, or thing being described. With some sentences, though, you must consider the larger context and intention to determine how clear the noun or pronoun is.

Summary

• An adjective clause is a group of words the act together to describe a previous noun or pronoun.

• Use commas with adjective clauses only when the noun or pronoun is sufficiently specific and clear.

Commas with Adverb Clauses

It might be easier to consider a few examples of adverb clauses before reading the complex definition (adverb clauses underlined):

I must leave before the party ends.

When Nora wants to sing, we hide.

The movie E.T. was banned in Sweden because it showed parents acting hostilely toward their children.

We decided to travel by car to Idaho, even though it will be a ten-hour drive.

As the above examples show, an adverb clause has the following characteristics:

1. It is a group of words that must include a subject and verb, even though the adverb clause cannot stand by itself as a complete sentence.

2. An adverb clause begins with a subordinating conjunction, such as before, when, because, even though, although, or since.

3. The group of words work together as a single adverb that modifies a verb, an adjective, or another adverb.

The best-known function of an adverb clause is modifying a verb, and it is this type of adverb clause that is sometimes confusing in terms of punctuation. Thus, we focus on this function of an adverb clause.

What’s the Problem?

Adverb clauses by themselves pose few problems; they come easily to most people and frequently appear in speech and writing. The problem is whether to use a comma to separate the adverb clause from the rest of the sentence. Two of the preceding examples use commas in this way, while the other two do not.

This hint will serve you well most of the time, but read the following sections to understand the exceptions, which do occur fairly often.

Adverb Clauses at the Beginning of a Sentence

Most adverb clauses can be placed in different positions in a sentence, and putting an adverb clause at the beginning of a sentence is common. Indeed, the resulting structure is simply one type of an introductory element. The same concept applies again: in general, use a comma to set off the introductory element, whether it is an adverb clause or some other type of introductory element.

While I was reading a fascinating book on grammar, the electricity went out.

Since our company was founded in 1902, the president has held an annual picnic for all employees.

At one time, most grammar handbooks urged putting a comma after all adverb clauses that come at the beginning of a sentence. However, the trend now is that a writer can leave out a comma after a short adverb clause (fewer than five words, or so most handbooks suggest).

When Jane arrived Tarzan was in the backyard.

If Neil calls we should not talk to him.

In fact, you might find that some readers, especially in the business sector, prefer that you not use a comma after an introductory adverb clause unless the clause is long. This trend is growing, but most handbooks still indicate a preference for using a comma after introductory adverb clauses. Thus, we suggest you keep it simple whenever possible and put a comma after all introductory adverb clauses (short or long)—unless you encounter readers who insist on leaving commas out.

Adverb Clauses at the End of a Sentence

In general, do not use a comma before an adverb clause. Some people mistakenly use a comma in such situations simply because they “feel” a pause. This is especially the case with adverb clauses that begin with because.

X I incorrectly want to use a comma, because I sense a pause in the sentence.

X Beefalo is what you get, when you cross buffalo with cattle.

X Aluminum is cheap, since it is the most common metal in the earth’s crust.

To correct these errors, you merely need to omit the commas:

I incorrectly want to use a comma because I sense a pause in the sentence.

Beefalo is what you get when you cross buffalo with cattle.

Aluminum is cheap since it is the most common metal in the earth’s crust.

Why do we set off adverb clauses that appear at the beginning but not at the end of a sentence? A comma is used to set off an introductory clause so readers will have a clear sign as to where the “real” sentence begins. There is usually no other reason to set off an adverb clause, so avoid using a comma with adverb clauses that appear anywhere else.

But the hint noted earlier indicates that there is an exception, and here it is: Use a comma before the sentence-ending adverb clause when it deals with a strong sense of contrast. Such clauses usually begin with even though, while, although, or though.

She was ready to leave the party immediately, while her husband wanted to stay all night.

I remember that the Lone Ranger’s horse is named Silver, though I keep forgetting that Tonto’s horse is named Scout.

It is not altogether clear why the rule evolved this way. Most likely, the comma helps readers see that the last part of the sentence will involve a strong contradiction or contrast with what came before. This structure is not rare in speech or writing, and overgeneralizing this situation causes many people to err by putting a comma before other types of adverb clauses. Again, the norm is that a comma should not set off a sentence-ending adverb clause. As with any rule, it can be broken when writers feel they want to emphasize an idea or achieve some other effect, but you should avoid intentionally breaking the rule in formal writing unless you are certain of a positive effect.

Summary

• Use a comma after an adverb clause that comes at the beginning of a sentence.

• You have the option of omitting the comma if the introductory clause is fewer than five words.

• Rarely should you use a comma before an adverb clause that comes at the end of a sentence.

• However, use a comma before the adverb clause if it involves a strong sense of contrast and begins with words such as even though or although.

Commas with Appositives

An appositive is a noun or pronoun that renames another noun or pronoun. Most commonly, the appositive is a noun appearing almost immediately after another noun. Notice how the appositive seems to bend back to rename a previous noun (appositives underlined):

My dog, Pearl, is a husky.

Shari talked to her lawyer, Perry Mason.

An appositive phrase includes not only a noun but words describing it. In this next example, president is the appositive, but it is described by the twenty-ninth and of the United States. All these words together are bending back to rename Woodrow Wilson.

Woodrow Wilson, the twenty-ninth president of the United States, said that automobiles symbolized “the arrogance of wealth.”

What’s the Problem?

As you have seen, appositives are frequently set off by commas. However, this is not always the case, as evidenced in these examples:

My friend Nicole helped write this report.

Shakespeare’s play The Tempest was the inspiration for a 1956 movie called Forbidden Planet.

Appositives with Commas

Nonessential information is often set off by commas. This basic guideline applies to other types of grammatical structures as well (for instance, see “Commas with Adjective Clauses” in this chapter). Although all appositives add clarity and detail, most are not crucial. Here, for example, the appositive (underlined) clarifies exactly who the doctor is:

I contacted our family physician, Dr. Stout.

Assuming the writer has only one family physician, you could leave out the appositive and not confuse readers. Sure, they would not know the name of the doctor, but the appositive is not essential because the writer has only one family physician.

The safest approach is to assume that an appositive needs commas, for usually the rest of whatever you are writing makes the appositive nonessential.

Appositives Without Commas

In general, do not use commas to set off words that are essential to the overall meaning of a sentence. The problem is sometimes it seems every word is important. However, as discussed earlier, the key with appositives is to look at the words they rename and consider how confused readers would be without the appositive. An appositive is essential when readers must have it to understand which person, place, or thing you have in mind. In such cases, you must leave out the commas.

X My friend, Jewel, needs a ride. (Confusion: Which friend? We assume you have more than one.)

My friend Jewel needs a ride.

X You need to read the book, The Color Purple. (Confusion: Which book? There must be millions of books available.)

You need to read the book The Color Purple.

Here are more examples of appositives that correctly omit the commas. Note how each appositive eliminates confusion by reducing the various ways readers could interpret each sentence.

The children’s song “Ring Around the Rosie” originated during the bubonic plague.

The country Denmark has had the same national flag longer than any other nation in history.

The French ruler Napoleon Bonaparte knowingly financed his Russian invasion with counterfeit money.

Sometimes It Can Go Either Way

On a few occasions, an appositive might be essential or not depending on what readers already know about the word being renamed. Consider again this sentence. It is fine as written if it could only be referring to one dog.

My dog, Pearl, is a husky. (OK if the writer has only one dog.)

But what if the writer has more than one dog? The appositive is essential because we are not sure which dog the writer has in mind. In this case, the appositive should not be set off by commas.

My dog Pearl is a husky. (OK if the writer has more than one dog.)

As you can see, the matter is usually settled by what the writer stated in previous sentences or by what the reader knew even earlier.

Summary

• An appositive is a noun or pronoun that renames a previous noun or pronoun.

• In general, use commas to set off appositives.

• Leave out the commas, however, when the appositive is needed in order to prevent confusion.

Commas with Adjectives

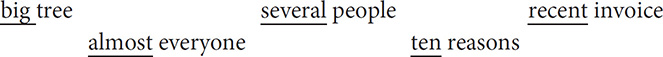

An adjective is a word that describes a noun or a pronoun. That is, an adjective describes the characteristics of a person, place, or thing. As seen in these examples, most words that are adjectives appear immediately before the word being described (adjectives underlined):

As will be explained, there are different types or categories of adjectives. The term coordinate adjective refers to adjectives that are in the same category.

What’s the Problem?

Most people know that adjectives can be strung together before a noun, as in a big, lazy, ugly cat. However, many people mistakenly believe that such adjectives must be separated by commas. The truth is that not all adjectives are separated by commas. Compounding the problem is that, even though most of us know what an adjective is, the punctuation decision depends on the lesser-known fact that there are different categories of adjectives.

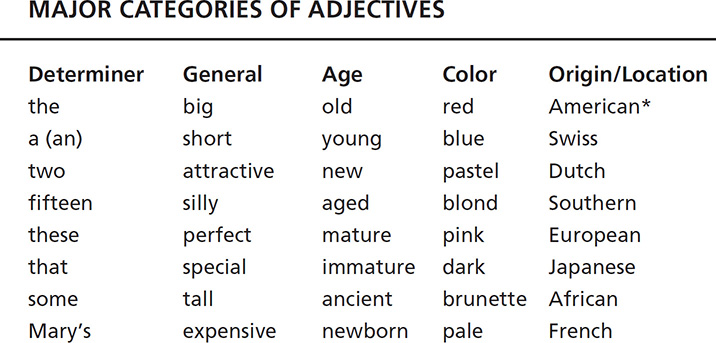

As seen in the table that follows, there are different categories of adjectives depending on the type of description they give. For example, some adjectives deal with amounts, while others deal with age. Again, only adjectives that fall within the same category are set off by commas. Coordinate adjectives are adjectives that fall into the same basic category.

Fortunately, it is not necessary for you to memorize all these categories, although knowing the rule can help you explain the truth to people who mistakenly believe all adjectives are separated by commas. The following tip will make it easier to punctuate consecutive adjectives:

Using Commas Between Adjectives

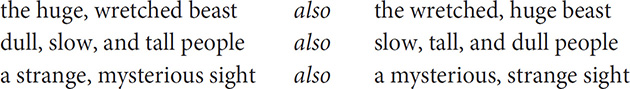

All of the following examples are correctly punctuated because the adjectives can be put in a different order:

Your intuition—though not always the best basis for punctuation—should tell you that each of these versions sounds natural. Thus, use a comma between the coordinate adjectives.

Think of it this way. The word coordinate basically means “equal in status.” Things that are truly equal can be switched around, as with coordinate adjectives. Or you can simply not think about the term coordinate adjective at all, and just remember that adjectives that can trade places with one another must be separated by commas.

If in doubt and all else fails, we suggest putting a comma between adjectives. Most adjectives fall into one category (general), so chances are that the adjectives you might string together are in this class, meaning they are coordinate and require commas. Again, play the odds only if you cannot make a better determination.

Omitting Commas Between Adjectives

Do not use a comma between adjectives from different categories. Or put more simply, if the adjectives cannot be switched around, do not use a comma. Keeping the nots in mind can help you remember this rule: Cannot switch, do not use a comma.

Notice how awkward these adjectives sound when they change places; meaning they should not be separated by commas:

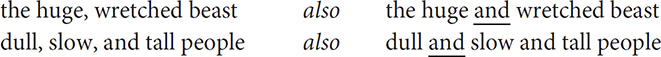

A Quick Look at the and Tip

Notice how you can also use and between the coordinate adjectives covered earlier:

However, trying to put and between other adjectives proves that you should use commas:

Summary

• Commas sometimes go between adjectives in a series, and sometimes they do not.

• Use a comma between coordinate adjectives (adjectives that can be switched with one another).

• Do not use a comma between adjectives that fall into different categories (adjectives that cannot trade places with one another).

* It is unlikely you would string together so many noncoordinate adjectives, but notice how they would sound best in the order presented here: determiner, general, age, color, origin/location. The scheme is reliable, but there are exceptions because it is a matter of intuition, not science. For instance, dark might refer to a color or to a mood (in the latter case, it would be a general adjective).