17

Parallelism

When we use a coordinating conjunction to join two or more elements of the same type, those elements are said to be parallel with each other. The elements that are made parallel by the coordinating conjunction can be nearly anything: words, phrases, or clauses. But there is a huge catch: the parallel elements must all be of exactly the same grammatical category.

When we join two or more elements together with a coordinating conjunction but the elements are not of the same grammatical category, then we made an error called faulty parallelism. Here is an example of a sentence with faulty parallelism:

X Donald loves eating pizza and to watch reruns of Baywatch.

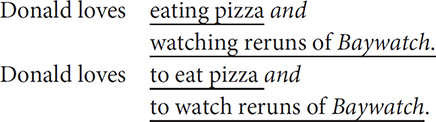

The problem with this sentence is that the coordinating conjunction and is used to join phrases that are not the same type: eating pizza is a gerund phrase, while to watch reruns of Baywatch is an infinitive phrase. What is tricky is that they are both noun phrases being used as the object of loves. That is not enough; they have to be the same type of noun phrase. To eliminate the faulty parallelism, we can do either of two things:

1. We can use parallel gerund phrases:

Donald loves eating pizza and watching reruns of Baywatch.

2. We can use parallel infinitive phrases:

Donald loves to eat pizza and to watch reruns of Baywatch.

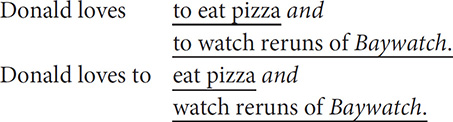

The best way to monitor for faulty parallelism is to make sure that the grammatical structure on the right-hand side of the coordinating conjunction is matched by an identical structure (or structures) on the left-hand side of the coordinating conjunction. A good way to ensure that the elements joined by the coordinating conjunction are actually the same is to arrange the elements in what we might call a “parallelism stack.” In a parallelism stack, the parallel elements are placed in a column so that it is easy to see whether or not the elements have exactly the same form. Here are parallelism stacks for the two legitimate examples just given:

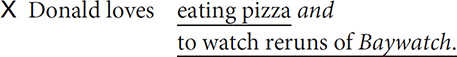

When we use a parallelism stack with elements that are not actually parallel, the error is easy for our eyes to spot:

Another important feature of a parallelism stack is that it helps us determine what is actually being made parallel. Compare the following sentences:

Donald loves to eat pizza and to watch reruns of Baywatch.

Donald loves to eat pizza and watch reruns of Baywatch.

When we compare the parallelism stacks for these two sentences, we can see at a glance what is parallel to what:

In the first example, the parallel elements are infinitive phrases beginning with to. In the second example, the parallel elements are verb phrases without the to. Either way is perfectly grammatical.

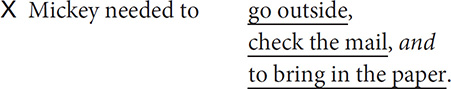

Probably the single most common situation in which faulty parallelism occurs is when there are supposedly three (or more) parallel infinitives, for example:

X Mickey needed to go outside, check the mail, and to bring in the paper.

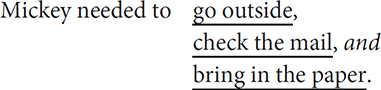

The parallelism stack shows that the three elements are not actually parallel:

In this sentence, the writer was not consistent about what was being made parallel. The first two elements are parallel verb phrases (go and check), but the third is an infinitive (to bring). We can have a set of three parallel verb phrases or a set of three parallel infinitives, but we cannot have a mixture. Here are the two correct ways of handling the parallelism:

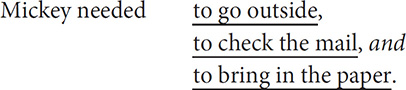

1. Make three parallel verb phrases:

2. Make three parallel infinitives:

Predicate adjectives and predicate nominatives are a common source of faulty parallelism, for example:

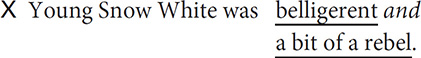

X Young Snow White was belligerent and a bit of a rebel.

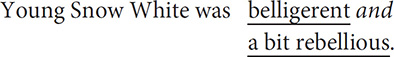

Here, the writer has made an adjective (belligerent) parallel to a noun phrase (a bit of a rebel):

The easiest solution would be to make them both predicate adjectives:

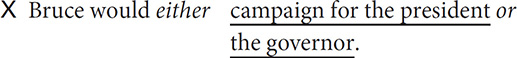

A common source of faulty parallelism involves correlative conjunctions in which the first element is misplaced so that the intended parallelism is derailed, for example:

X Bruce would either campaign for the president or the governor.

The parallelism stack shows the problem:

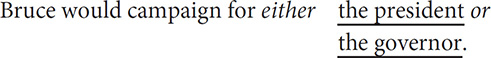

The writer has inadvertently tried to make a verb phrase (campaign for the president) parallel to a noun phrase (the governor). The solution is to move either so that it is adjacent to the element that the writer wants to make parallel:

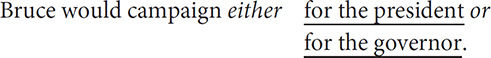

The writer could also have repeated the for to make parallel prepositional phrases:

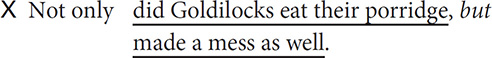

When a writer begins a sentence with a correlative conjunction, the writer is then committed to comparing two whole clauses, not a clause with just a piece of a clause, for example:

X Not only did Goldilocks eat their porridge, but made a mess as well.

The parallelism stack shows us the problem:

The first element is a whole clause, but the second element is only a verb phrase—a piece of a clause. The simplest solution is to make both elements complete clauses:

Sometimes what counts as faulty parallelism is surprising. When we use a string of three or more noun phrases, the first two noun phrases establish a pattern of modification. If the pattern is then broken, it is faulty parallelism, for example:

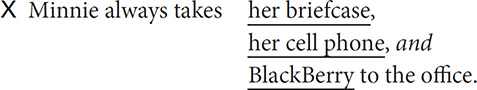

X Minnie always takes her briefcase, her cell phone, and BlackBerry to the office.

Here is the parallelism stack for this sentence:

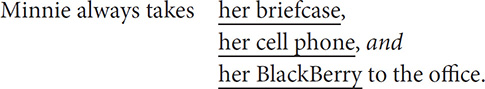

We need to make the third noun phrase follow the same pattern of modification as the first two noun phrases:

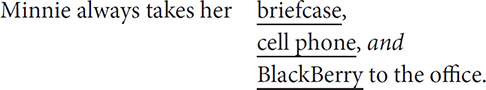

The other possibility would be to strip the modifiers so that the parallel items are all bare nouns:

Summary

Parallelism is surprisingly finicky. Anytime you use a coordinating conjunction, you should look at the element after the coordinating conjunction and then work backward through the sentence, making sure that any other parallel elements have exactly the same form. The parallelism stack is a handy way of working through more complicated examples of parallelism.