18

Grammar Etiquette for Digital Communication

This chapter offers guidance regarding the increasingly complex and varied world of online communication. This chapter covers digital formats such as cellphone texting, instant messaging, e-mail, and online social media, and anticipates future modes of electronic writing that will undoubtedly offer new ways to communicate with individuals and groups. Hundreds of books, websites, and articles offer advice concerning online etiquette in general—for example, in showing appropriate respect and courtesy. Such advice typically deals with technical matters (such as refraining from sending e-mail with overly large attachments) or with avoiding rude comments and emotional outbursts (also known as flaming).

However, our chapter focuses on how language choices in digital communication affect clarity and whether the writer is perceived as polite and considerate. As far as possible, this chapter avoids technical matters and the generic ways writers may demonstrate respect and consideration for online readers. Instead, we deal with the linguistic problems that occur all too often in digital writing.

1. Two laws of grammatical tolerance in virtual writing. Writers should keep in mind two principles as they consider the role of grammar, usage, and proofreading in electronic texts: (1) the Virtual Law of Grammatical Tolerance and (2) the Virtual Law of Grammatical Intolerance. The fact that these are often in conflict does not lessen their validity. Writers need to be aware that few readers abide solely by just one of these principles.

2. Choosing to avoid textspeak in general. Most grammatical, usage, punctuation, typographical, and misspelling errors occur intentionally: writers know they exist, or they would notice them if they bothered to proofread. Thus, this chapter offers several reasons why we need to shun the excesses of textspeak.

3. Particular textspeak to avoid: abbreviations, misspellings, and emoticons. Relatively few textspeak features are both useful and clear for a diverse range of readers. While some of these features might be useful in casual situations, most textspeak should be avoided.

4. Understanding the limits of grammar and spell checkers. Despite modest gains, editing programs are limited, especially grammar checkers. An increasing number of electronic modes of writing have built-in editing software. Understand that these programs still struggle with a number of grammatical structures.

5. Neither overuse nor underuse certain keyboard choices. Many online writers use far too many exclamation points and other punctuation marks or symbols, while other writers use too few. Both extremes create unclear communication and credibility problems.

What’s the Problem?

Rules for formal English were not written with virtual discourse in mind. Grammar rules and usage conventions originated long before the advent of digital communication (or even manual typewriters). The proliferation of usage and grammatical errors in electronic texts, also known as e-texts, shows that this evolving medium of communication is gradually developing its own rules and conventions. To compound the problem, the term digital communication is misleading, for it implies that all electronic writing is the same. In truth, the writer’s unique situation and audience are what primarily determines his or her best linguistic choices. The setting does matter somewhat; for instance, readers are generally more tolerant of misspellings in instant messaging than in e-mails. Some important generalizations regarding grammatical etiquette can assist writers in almost any mode of communication.

As people try to figure out how to behave linguistically in diverse online situations, they should realize that two rules are already so widely accepted that we submit them here as the two laws of grammatical tolerance in virtual writing.

On one hand, readers tend to forgive grammatical errors in text messages, e-mails, posts on social networking websites, and other e-texts. This tolerance is largely due to the casual nature of much of our virtual discourse. What people refer to as textspeak is a digital hybrid of writing and everyday speech, although some textspeak features (such as “smiley faces” and other emoticons) are associated with neither casual speech nor ordinary writing. Given the informal nature of e-texts, people normally try to expend the least effort and time; they treat electronic writing as everyday conversation rather than formal writing. This tendency results in textspeak, an informal dialect innocuously used in countless instances of digital communication.

On the other hand, a plethora of online reactions in forums and chat rooms offers solid proof that there is a danger in assuming that digital writers have a grammar pass. Indeed, online responses to grammatical errors often become so heated that they turn a pleasant forum discussion into a divisive squabble replete with name calling and outright rudeness. One side takes the aforementioned Law 1 as its unassailable defense and Constitutional Right, while self-appointed grammar police try to uphold only Law 2. These interactions rarely end well.

Choose to Avoid Textspeak Errors

In light of the semi-conflicting laws of grammatical tolerance in virtual writing, how do we approach grammar in e-texts? The dilemma will persist as online social networking and the writing it entails become increasingly popular, not only with individuals, but also in businesses and organizations that conduct their internal and external communication through networking texts and websites. Even though the rules for these emerging forms of writing have yet to be worked out completely, there are commonsense guidelines you can follow, starting with the following all-important approach.

Textspeak errors are usually the result of a choice made by the writer: either they facilitate typing, or they are mistakes the writer assumed were not worth checking or correcting. These errors include: not capitalizing even the first word of a sentence, omitting sentence-ending periods, “shorthand misspellings” (such as r for are), keyboarding mistakes the writer decides to overlook, “cute” abbreviations (such as B4N, that is, “bye for now”), or even multiple punctuation marks (as in ?????). Because almost all such textspeak features are a matter of choice, we can eliminate many errors by avoiding textspeak and proofreading our e-texts after writing. Too many people believe the rules for formal English are not worth applying.

Even the most rule-resistant adult, however, will admit that grammatical errors can confuse readers, as well as create a credibility problem for the writer. Therefore, why not abide by the rules and conventions that literate readers expect in both electronic and hardcopy text? Remember that hardly anyone is bothered, or even notices, when an e-text avoids misspellings, uses apostrophes to show possession, or shuns obscure symbols such as ,!!!! (representing “talk to the hand”). As you know, slangy textspeak and grammatical mistakes appear in e-texts for many reasons. In particular, such writing is often highly informal, if not lax, because it is typically intended for friends, dashed off on a laptop while you’re multitasking, walking, or on public transportation—often keyed one-handed onto a tiny keyboard on a mobile phone. Still, these excuses don’t work when errors cause miscommunication or annoy readers who assume either (1) that you don’t know simple English rules, or (2) that you believe your interlocutor isn’t important enough for you to respect the rules.

Indeed, this is why people often feel personally insulted by these errors: they believe you know the rules, but you don’t think your readers are worthy of the scant time it takes to tidy up an e-text. While you might recall that you dashed off the message while cleverly hiding your texting device during a boring meeting or class, your interlocutor doesn’t know those details—and probably doesn’t care. Your reader has to deal with what you sent, not your situation.

In other words, should readers be obliged to imagine your environment or wait for you to explain what you meant to say in an error-plagued e-text? From personal experience, we can attest to multiple instances when college students e-mail their writing teachers to complain about a grade, claiming, in a text riddled with misspellings and punctuation errors, that in fact they are excellent writers, and that the poor grade on an assignment was a severe miscarriage of justice. One student, when informed how incomprehensible his e-mailed complaint was, testily replied: “Duh Im getting my hair cut right now trying to email giveme a break!!!!” As you might suspect, his poor understanding of how to persuade—let alone his linguistic choices—did not make a compelling case for rewarding him with a better grade.

In short, do not misconstrue the Virtual Law of Grammatical Tolerance to mean you know which errors will alarm or confuse your virtual readers—especially when you do not know your audience well, if your readers believe the situation is even marginally formal, or if you have any doubt as to whether they expect Standard English.

This is an issue worth considering in terms of one’s career: an increasing number of businesses and organizations allow or require online submission of résumés and job applications. Employers make decisions not only on the content of your application materials, but on your language choices. In the case of applications, you must assume that all employers abide strictly by the Virtual Law of Grammatical Intolerance.

Individuals, not only corporations, make immediate generalizations about your character and personality based on your language—even in informal online situations. This is especially true when your reader knows little or nothing about you other than how you present yourself in the e-text. Often, readers make unfair generalizations as a result of a few “minor” word choices you have made. It’s what humans do.

One matchmaking website (http://blog.okcupid.com) offers evidence of this tendency, as exhibited in casual e-texts between individuals seeking to find a compatible dating partner. The company analyzed some 500,000 “first contacts” between prospective partners. A computer program determined which keywords and phrases were associated with successful replies from one potential date to another. Their number-one finding is “Be literate.” Four of the five worst words seen on this website are textspeak misspellings: ur, r, u, ya. The fifth-worst error (cant) is also seen in casual hardcopy writing, as are other mistakes likely to annoy or put off a potential partner (spellings such as realy, luv, and wont). Whether they stem from “pure textspeak” or carelessness, these choices are unlikely to impress people who only have such messages to go on when they are sizing each other up.

Some of the most widespread errors in digital writing (not merely in courtship interactions) are misspellings and not capitalizing proper nouns or, more often, the first word in a sentence. Do not mistake frequency for acceptability. Misspellings confuse people and are likely to create a credibility problem. While readers might guess that a writer knows the first word of a sentence ought to be capitalized, they no longer assume that someone knows how to spell. If a person spells school as skool, many readers will assume the writer never learned to spell the word.

Most online misspellings of everyday words are deliberate choices, usually made to save a few precious keystrokes. This shorthand in textspeak is related to another problem: omission of apostrophes in contractions, as we saw with cant that did not impress possible dating companions. Although contractions are often acceptable even in formal writing if used judiciously (we ourselves don’t always avoid them in this book), you should at least provide the apostrophe—unless, again, you expect no criticism, as in a quick text message to a close friend (see Chapter 12 on contractions).

Capital letters obviously indicate where a new sentence begins. You might imagine that periods (or other sentence-ending punctuation) do a fine job of this already, but the concept of where a sentence begins and ends is so important that English, along with many other written languages, long ago developed a useful “redundancy.” In writing, we use both capitalization and punctuation to make sure readers detect sentence boundaries. This takes the place of intonation and body language that in spoken discourse allows listeners to know when a new sentence or idea begins. (Later in this chapter we discuss the perils of overusing capital letters.) Sadly, many e-texts leave out both periods and capitals, and this “double whammy” is especially likely to confuse and/or annoy readers.

gA corollary of the Virtual Law of Grammatical Intolerance is that you should never assume that tolerance of textspeak in your digital writing extends to hardcopy writing, except perhaps in an informal note or letter aimed at a casual reader (a friend) whom you know will enjoy cryptic abbreviations, cutesy emoticons, shorthand misspellings, unorthodox capitalization, etc. While older adults rarely let textspeak leak into formal writing, it is becoming more common for less experienced writers to forget that textspeak is not an all-purpose way of communicating.

Judiciously Using Abbreviations and Emoticons

Keeping in mind the Virtual Law of Grammatical Tolerance, we know there are times when textspeak is acceptable, even functional. In fact, research done by the matchmaking website mentioned earlier shows that the acronym LOL (laughing out loud) creates a favorable impression with a prospective dating partner (don’t overdo it, lest you seem overeager). When such language works, it is when the writer has considered the particulars of the discourse situation, such as the importance of humor.

E-texts are often brief. In texting, the writer must limit a message to a preset number of characters. Because of this brevity, even e-texts free of grammatical errors can send the wrong or an imperfect meaning. Suppose you text a friend to see if she can meet you for lunch, and her response is “Why would I do that?” You could imagine she is curious, rude, or trying to be funny. Without cues from her body language, you have to rely on the tiny message, and you might assume the worst (i.e., you have at least one ill-mannered friend).

Fortunately, people have developed distinctive ways of making e-texts both brief and less ambiguous. If your friend had included LOL at the end of her text, you would have understood she was trying to be funny. You could reply with “I thought you could repay me for treating you last week  ”. Like LOL, the smiley-face emoticon, along with other symbols that convey emotion, has provided digital communication with a unique “grammar”—an accepted set of pragmatic linguistic rules. Thus it is okay to include a reasonable number of e-text emoticons and abbreviations in a text message (including some shorthand misspellings)—as long as you follow all three of the following guidelines.

”. Like LOL, the smiley-face emoticon, along with other symbols that convey emotion, has provided digital communication with a unique “grammar”—an accepted set of pragmatic linguistic rules. Thus it is okay to include a reasonable number of e-text emoticons and abbreviations in a text message (including some shorthand misspellings)—as long as you follow all three of the following guidelines.

When to Use Textspeak

1. Avoid textspeak features such as emoticons and abbreviations when (1) the situation is formal, (2) you want to impress your audience in a professional or serious way, or (3) you do not know much about your audience.

2. Use textspeak choices that are widely known, unless your aim is to confuse your audience. You will most likely know whether they will recognize your more obscure or cryptic choices.

3. Above all, make sure you have a good reason for using textspeak features: you are aiming either to set a suitable tone or to prevent miscommunication.

The tips listed above require explanation. For example, there is no infallible way to know what is (or is not) a “formal” situation where textspeak might be useful. In fact, it’s usually not an either/or decision. Writing to co-workers, a customer or client, your teacher, or an employer is not necessarily so formal that you must avoid all emoticons and abbreviations—especially if they may prevent miscommunication. To make a sound decision regarding our three guidelines, consider two questions regarding your intent and your audience:

1. What tone do you want to establish with your readers? If you want to indicate that you are serious and professional, avoid textspeak entirely, even if it means you cannot be as brief, humorous, or clever.

2. What tone has the audience set? If your reader has adopted a tone that is serious and professional, you should forego all textspeak features and write out your thoughts using more formal and complete language. This assumes, of course, that you care about your reader’s reaction. In most cases, you ought to. This is the basis of clarity and etiquette—grammatical or other. (Being respectful also helps you reach whatever goal you had in mind when you wrote your message.)

Which abbreviations might contribute positively to e-texts? We suggest a conservative approach. Stick with widely known, inoffensive choices—although these might change as fashion changes. Keep in mind the three guidelines earlier in “When to Use Textspeak,” and always play it safe. For instance, use even your safe choices only in certain modes of digital writing, such as informal texting, instant messaging, posts on social networks, or in online forum discussions where other contributors are already using the same kind of textspeak. However, in e-mail messages, it is best to avoid textspeak in communication that is even remotely formal or that can become formal (if a supervisor is on the recipient list, for example). Consider not just the medium but your audience and your purpose. An instant message can be highly formal, say, if it is run on your company’s customer-service website.

Certain acronyms and initialisms have become infamous textspeak features; to outsiders, they are cryptic abbreviations that originated (or became popular) among online writers. They are still used most appropriately within the social groups that created them.

We list a few functional and widely acceptable abbreviations here. As with almost all e-text abbreviations, they may appear in either lower- or uppercase. Note that using capital letters makes it clear that they are abbreviations. They can be useful to both writers and readers when circumstances permit a degree of informality.

Widely Acceptable and Useful E-Text Abbreviations

BTW: By the way. This acronym shows you are introducing a topic casually. It allows you to jump to the topic without including pesky transitions.

FAQ: Frequently asked questions. Use this acronym to refer someone to a web page that covers questions people often ask about a particular product, issue, or problem (as in “Search the forum’s FAQ page if you have other questions.”).

f2f: Face to face. This reference to a nondigital, in-person meeting usually appears in lowercase. It can be an adjective (“We need a f2f meeting.”), a noun (“We need a f2f.”), or an adverb (“We need to meet f2f.”).

FYI: For your information. This can indicate you do not necessarily expect (or want) a response to something you’ve included. In speech, saying this entire phrase can make you appear irritable or testy, but it doesn’t function that way in e-texts.

IM: Instant message. This can be a verb (“IM me tonight.”) or a noun (“The IM you sent is unclear.”). Some people use it to refer to phone texts as well as IM programs on a computer.

IMO: In my opinion. This initialism is useful in several ways. It indicates you are contributing something you are merely “tossing in,” without eliciting debate or a serious response. Avoid the less-common IMHO (“In my humble opinion”), which ends up sounding meek.

LOL: Laughing out loud. To use this acronym, you do not really have to be laughing or even amused. You’re indicating that your message is not meant to be taken too seriously. Or you might be laughing politely at someone else’s attempt at humor. Avoid using the numerous LOL variants. Even the more common ones (such as ROFL [“rolling on the floor laughing”]) add little to LOL and can be unfamiliar to readers.

Caution: Do not assume, especially in professional and business settings, that your English-speaking readers in other countries understand common abbreviations used in the United States. It’s possible that even highly proficient non-native speakers of English express these ideas differently. In addition, not all English-speaking countries share the same textspeak conventions (just as they do not all use the same spellings in hardcopy writing).

Even native speakers of American English can be confused by abbreviations that are ordinarily used by you and your circle of friends. These terms are probably not familiar to enough people to warrant inclusion on any “most popular” list. Following is our “B-list” of terms that fall into this category. It might include your personal favorites; but please avoid these hunless you know your readers well, you are sure they can interpret them correctly, and that they accept them as facilitating communication.

“Common” E-Text Abbreviations That Still Confuse or Annoy

BRB: Be right back. Although useful in texting and IMs, this still mystifies many readers and is almost never useful in e-mails or other e-texts. Also avoid variants such as BFN and B4N, meaning “Bye for now.”

K: Okay. Even ok would be a better option.

NP: No problem.

OMG: Oh my god/gosh. This acronym is not functional, except in very informal e-texts where you want to express great surprise or dismay (too often followed by an excessive number of exclamation points).

SNAFU: Situation normal, all “fouled” up. Although this is one of the rare e-text acronyms that appeared before e-mails and texting, it has yet to become current or acceptable (the F can stand for a word that offends some readers’ sensibilities).

THX: Thanks. This one is usually easy to decipher, but most correspondents who are truly grateful will take time to write out the idea (or even send a quaint hardcopy thank-you card).

WTF: What the f***? Although this term has taken on a prolific life beyond e-texts (on t-shirts in particular), it has no place in formal writing—one reason we don’t spell it out here.

Y: Yes. People often interpret this lonely letter as Why?, which sends a different meaning from what the writer intended. It makes the writer appear inquisitive, and not simply in agreement.

The Only Emoticon You (Might) Need

An emoticon (emotion + icon) is a graphical “picture” that allows the writer to express certain attitudes, feelings, or sentiments. We think these are best omitted from all writing except for extremely casual communication. Emoticons began with keyboard characters that, when set in close proximity, vaguely resemble a face turned on its side and eerily having no skull. The best known and oldest is the smiley face emoticon comprised of a colon, dash, and half a parenthesis: :-)

Today most word-processing, texting, and e-mail systems automatically turn these keyboard strokes into an image (with a perfectly round skull), for example:  . Either the “old school” version or the happy-face icon can indicate, as mentioned earlier, that you are attempting to be humorous (or at least not totally serious). This emoticon is useful if you are not sure your humor will be understood by unperceptive readers, if you want to make it seem that you are “just kidding” while suggesting something they might not wish to hear, or to express simple pleasure. We believe the smiley face emoticon is the only one that generally has value in e-texts. Other variants are used, of course, in informal messages to friends and family, such as the sad :-(or the winking ;-) face.

. Either the “old school” version or the happy-face icon can indicate, as mentioned earlier, that you are attempting to be humorous (or at least not totally serious). This emoticon is useful if you are not sure your humor will be understood by unperceptive readers, if you want to make it seem that you are “just kidding” while suggesting something they might not wish to hear, or to express simple pleasure. We believe the smiley face emoticon is the only one that generally has value in e-texts. Other variants are used, of course, in informal messages to friends and family, such as the sad :-(or the winking ;-) face.

The variant emoticons have a problem: like a wink on a real face, a nuance in a smiley face can imply different things—an inside joke, a secret, or even a romantic flirtation. Add to this that emoticons, like textspeak acronyms, tend to be interpreted differently in different parts of the world. Thus in most e-texts, the traditionally and almost-universally understood smiley face is the only emoticon worth including—and even then, only when it is functional and appropriate for your intention and audience.

Using Grammar and Spelling Checkers

Increasingly, all modes of digital communication—from smartphones to desktop PCs—have built-in programs that automatically try to find or fix misspellings, typographical errors, and assorted grammatical problems. Websites for social media often have grammar and spelling checkers built in so that any message or post a person might contribute will be automatically flagged or edited for correctness. These programs can be helpful, but be aware of their limitations.

Editing programs catch errors a writer might not detect, sometimes “correcting” them without bothering to ask permission. However, language checkers have too many shortcomings for you to be able to rely on them. They are poor decision-makers for grammar. One problem is that no computer program can effectively decipher meaning, even though language and punctuation choices depend almost entirely on the meaning the writer intended. Checkers also have difficulty with long sentences: they contain too many words, which, depending on the writer’s intention, could be grammatically connected in different ways.

Even though they are essentially handheld computers, cell phones and smartphones have built-in editing programs that are not as robust as those on most desktop computers or tablets. Keep in mind that mobile-phone texting is particularly apt to include errors that editing programs will miss or fail to correct. Another limitation is related to economics: There are relatively few companies producing the most popular editing programs. Without serious competition, these programs have not improved as much as one would hope, especially considering the great technological advances in other areas. Readers, however, will naturally blame the writer for errors, not the editing program.

Given the real limitations of all editing programs, here are three problems to monitor:

Limitation 1: Checkers Frequently Overlook Homophone Misspellings

Homophones are words that sound alike but have different spellings (such as to, two, and too). Spelling checkers, although far more reliable than grammar checkers, do not have even a young child’s understanding of meaning. As a result, these programs rarely notice that a writer has used the wrong homophone. You might inadvertently type to, instead of two, but the spelling checker would disregard this error, since both are legitimate spellings.

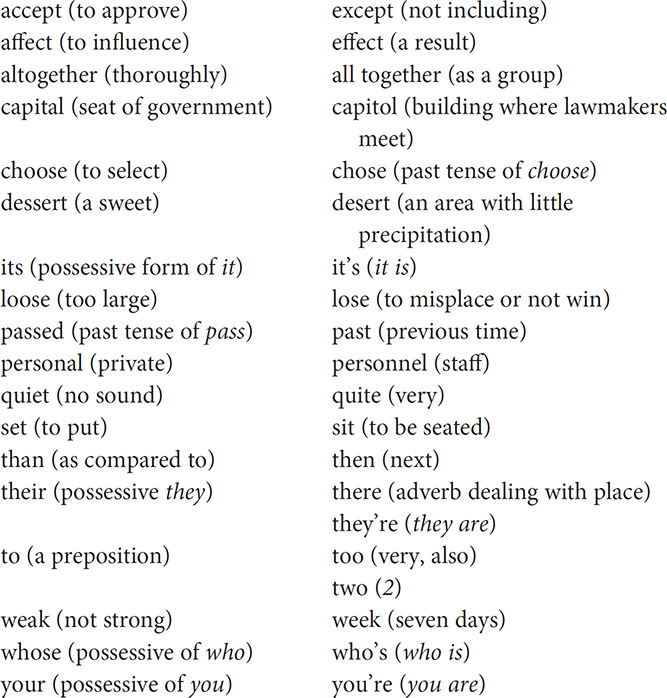

Here are some frequent homophones and near homophones you should never trust to a spelling checker (even those that claim to check words “in context”).

See Appendix A for a more complete list of homophones and other commonly confused words that spelling checkers usually overlook. Appendix B provides three different groups of words that checkers do tend to correct when misspelled. However, as noted previously, spelling checkers are not always available to you.

Appendix C is a list of incorrect phrases that, like homophones, will rarely be detected by a spelling or grammar checker. These “eggcorns,” as they are called, use the wrong words in common expressions, such as saying “a new leash on life” when the correct wording should be “new lease on life.”

Limitation 2: Grammar Checkers Are Easily Confused, Especially with Certain Structures

These programs cannot be trusted for punctuation and sentence structure. They often flag items as errors when they are not, and their “solutions” can worsen the problem. As we’ve pointed out, they can’t cope with long or complex sentences. They are also flawed in other areas. Inaccuracies occur with complicated syntax and with language choices that depend on meaning, which editing programs are not built to understand.

Below we list eight specific problems that grammar checkers often skip and structures that make them flag something as an error when it is, in fact, grammatically acceptable. In parenthesis, we refer to page numbers of this book where you can find more information on the structure in question.

• Certain sentence fragments: Incomplete sentences are difficult for grammar checkers to mark properly, except for the most glaring errors. In particular, sentence fragments beginning with which, because, and especially are difficult for a software program to catch. Sometimes complete sentences starting with these words are flagged as errors when they are actually correct. Both because and especially can legitimately start off an introductory element of a full sentence. At other times, these words are used at the beginning of an incorrect fragment that is missing a main clause. The word which is often accepted as correct, both in hardcopy and online, when it actually means this or that. However, some grammar checkers either always flag which as the first word of a fragment, while others do not detect it even when it begins a fragment (see pp. 112–116).

• Certain types of subject/verb agreement: The limits of grammar checkers are often obvious when a noun is separated from its verb by more than four or five words (text messages rarely have such a structure, but e-mails and other longer texts do). A grammar checker might not detect the subject/verb error in this sentence:

X The criticisms involving the last person who held this position is a problem we should not repeat.

Or it might mark an error in agreement when there is none, as in:

The criticisms involving the last person who held this position are problems we should not repeat.

In both instances, the modifying phrase between the underlined subject and the verb not only is long but has its own nouns and a verb. The grammar checker is confused because it does not know that the main verb of each sentence (is and are) is unaffected by intervening words (see pp. 124–130).

• Comma splices: These occur when you incorrectly use a comma (instead of a semicolon or a period) to separate two sentences, as in:

X I went home, I was hungry.

The problem, especially with longer sentences, is that a comma can play many different roles. The grammar checker assumes this instance is just one of its many functions (see pp. 119–122). Comma splices are common in texting and casual e-mails, but otherwise they can confuse and distract.

• Dangling modifiers: Noticing this error depends on our seeing that an introductory element has led to the wrong meaning, as in:

X Running down the road, my breathing became difficult (your breath ran down a road?).

Because your editing program does not understand meaning, it ignores this error (see pp. 200–204).

• Passive voice: Grammar checkers are almost universally programmed to reinforce the incorrect belief that use of the passive voice is an error, as in:

The ball was hit out of the park.

Too much use of the passive voice can lead to dull writing, but used in moderation, it is perfectly fine and is not a true error (see pp. 90–92).

• Commas and adjective clauses: A comma is needed to set off an adjective clause that is of little importance, as in

I saw Sarah, who was wearing a red coat.

Do not use a comma if the clause is essential, as in:

I saw someone who ignored me.

Grammar checkers do not know which clauses are important, so they don’t notice either extra commas or missing ones in adjective clauses (see pp. 60–61 and 217–221).

• Sentences with capitalized abbreviations: This can be a problem with e-texts that contain not only textspeak abbreviations (such as those discussed earlier) but also technical acronyms correctly used in workplace e-texts, as in:

BDNF and CNTF trials are available for ALS patients.

For some reason, grammar checkers sometimes mistakenly flag such correct sentences as fragments or other types of errors, or they ignore errors elsewhere in the sentence (even if you have set the grammar checker to ignore words that are wholly capitalized). Grammar checkers are especially confused by sentences that are in all caps (i.e., “shouting”).

• Vague pronouns: Many pronouns, such as it and most, usually refer to a previous noun or pronoun (the antecedent). However, computer programs rarely know if a reader is aware of the antecedents (or can determine if any are present). In particular, vague uses of this and that (without an antecedent) are almost never flagged by grammar programs, even though this error commonly occurs in writing (see pp. 140–141 and 148–158).

Limitation 3: Grammar and Spelling Checkers Often Go Awry When You Cut/Paste from E-Texts

It is common to cut and paste sections of e-mails, web pages, IMs, or even text messages into other documents. You might paste words or pictures into another e-text or a word-processing document. In doing so, you often unknowingly cut and paste the editing style from the old document along with the text; sometimes your device simply cannot incorporate the new style. This issue is not only limited to the copied material; if you continue composing, the problem often carries over to your own writing.

In short, if you cut and paste from (or into) an e-text, do not assume you have become “grammatically immaculate.” It’s more likely that your own editing program has been disabled. A technical solution is rarely simple and depends on the particulars of your word processing program and the way you cut/pasted. Try to go into editing preferences to find options that enable or disable the grammar and spelling checkers (look for the “Tools” menu). At the very least, realize you must become a better spelling and grammar editor yourself when a cut/paste involves e-texts.

Avoid Overdoing (and Underdoing) It

You also need to consider the unconventional choices you make in e-texts that merely seem sociable to you, but may often hinder communication. These include punctuation, symbols, and capitalization that mistakenly reflect a “more must be better” approach. While texting, for example, it is tempting for writers simply to press one key multiple times to convey an idea or tone, rather than choose better wording. As e-text fashions change, our list of tips will need to evolve, but the general advice will remain the same: be careful about overusing certain keyboard functions.

• Avoid repetitious exclamation points and question marks: Although multiple exclamation points and question marks might appear emphatic, just as often they seem rather adolescent, too emotional, or shockingly demanding (as in “OMG!!! Email me right now!!!”). Research studies suggest that readers of e-texts make some surprising generalizations. For instance, too many question marks in an e-mail can create an image of the writer as a confused or angry person.

• Don’t shout: Many writers persist in capitalizing their entire e-text, usually because they do not take the time to hit the shift key more than once. Not only does this make it seem that the writer is overly excited (“shouting”), a sentence in all caps is hard to read. In addition, some grammar and spelling checkers are confused by overcapitalization.

• Use ellipses sparingly: If you use multiple periods in a row (ellipses), realize that they can be interpreted in multiple ways. In hardcopy writing, they normally indicate that words have been omitted from a direct quotation. If this is what you wish to convey in an e-text, limit yourself to three periods per ellipses, or four at the end of a sentence (one of these stands in for the end period). Some writers use ellipses as all-purpose punctuation in e-mail and texting, rather than inserting commas or other punctuation that create clearer communication. Readers can mistakenly infer from ellipses that you are hesitant to give an opinion or are insinuating something, as in “I saw you at the park with your handsome new neighbor….” (If you really want to imply something here, you might as well use a smiley face.)

• Remove symbols, punctuation, or figures that clutter: People often drop in repetitious or unnecessary marks that might seem chic (such as #, also known as the “hash” or “pound” sign, frequent in certain social media). Such features tend to be distracting or indecipherable to many readers. Another source of clutter is an artifact of e-mail rather than fashion: entire walls of > (brackets) found in a series of replies. While brackets are useful in identifying older replies, they can easily take over an e-mail and, even worse, grow into a lengthy row within subject headings. Consider deleting at least some of these marks, or delete the older e-mail “stragglers” entirely.

Finally, our warnings against overdoing punctuation should not be identified with one of the most common errors in e-texts, especially on social networking sites and in texting: the avoidance of useful punctuation.

The increasing absence of punctuation is a hallmark of many e-texts—a phenomenon seen rarely in any other kind of writing. Earlier, we gave examples of how contractions in e-texts often fail to include an apostrophe, a situation that confuses both the writer and the reader. Apostrophes are also often omitted when they indicate possession, although this occurs in hardcopy writing as well. The comma and single period are not yet headed for extinction, but they have been slowly vanishing from e-texts, especially from instant messages, text messages, and posts on social networking websites.

As we mentioned earlier, keep in mind that periods are extremely useful in telling readers where ideas and sentences end. Indeed, “sentences” such as the following example are frequently seen in informal e-texts, especially phone texts:

X I want to call there are things I need to discuss

A reader will likely figure out that the writer does not mean “call there” and that this utterance is really two distinct statements. Still, effective communication should not require the reader to take the time to figure out such simple ideas.

Summary

This chapter has outlined the difficulties readers and writers face in implementing the most important communication development since the invention of the telephone: the use of electronic devices that allow us to key in and almost instantly send messages to other devices around the world. Incorporating elements of both hardcopy writing and day-to-day speech, electronic texts lack established guidelines, given their recent and evolving nature. However, general principles of communication still apply, and we all know that some grammatical and usage choices are more liable than others to hinder communication.

In particular, e-texts should use, at most, only the most common and functional features of textspeak, unless writers and readers are well known to one another and mutually accept a casual style. Textspeak abbreviations, misspellings, and emoticons, despite their popularity and occasional value, frequently create confusion and/or a poor image of the writer. In particular, conscious misspellings usually save the writer only a few keystrokes, while they often confuse or distract readers. People want to focus on the meaning of an e-text, not on its letters, icons, or syntax.

Grammar and spelling checkers have become essential tools, given the hurried way people key in and send their messages on petite keyboards. However, editing programs are, to say the least, imperfect, especially with complex or lengthy structures where the meaning of our words (not just their sequence) determines whether a sentence is grammatically clear and acceptable. We must be careful not to overuse certain punctuation and capitalization choices, while also remembering to use punctuation and capitalization that enhance clarity in e-texts as well as in hard copies.