4

Verb Forms

Tense

Tense is one of the most confusing (and confused) terms in English grammar. Part of the confusion is that tense refers, often quite inconsistently, either to verb form or to verb meaning. We will keep the two ways of looking at verbs—form and meaning—separate. A metaphor from chemistry may (or may not) be helpful here. Think of verb forms as the six basic elements that make up the verbal system. Some of these six basic elements can stand alone as meaningful verb expressions. Others can only exist when combined with another basic element in a sort of verb molecule. For example, what traditional grammar calls the future tense is such a molecule. Here is an example of a sentence containing a future tense (in italics):

I will go to the grocery store on my way home.

The future actually consists of two elementary verb components: will, a present tense form, and go, a base form.

We begin by looking first at verb forms and then turn to how these forms are used to create meaning.

Verb Forms

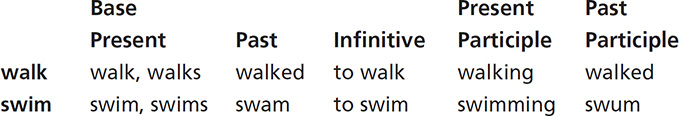

All verbs (with the exception of modal verbs, which will be discussed a little later) have six different forms. The six forms are listed here and illustrated by the regular verb walk and the irregular verb swim:

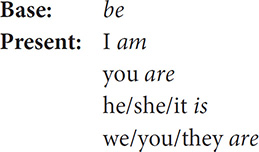

Base Form. The base form is the dictionary-entry form of the verb. For example, if you looked up the past form swam in the dictionary, the dictionary would refer you to the base form swim. At first, it may seem difficult to tell base forms from present forms because in nearly all cases, they are identical. However, there is one verb whose base form is completely different from its present form: the verb be:

We can use the fact that the base form of be is different from all its present forms to determine when base forms are used.

There are two quite common places where the base form is used: (1) in imperative sentences and (2) in the future tense.

Here are some examples of imperative sentences (verbs in italics):

Go away!

Oh, stop that!

Answer the question.

When we use the verb be in imperative sentences, we can see that the base form is used:

Be good!

Be prepared.

Be careful what you wish for.

If we attempt to use any present form of be, the results are clearly ungrammatical:

X Are good!

X Is good!

X Am good!

The future tense is formed by using the verb will followed by a verb in its base form. Here are some examples of future tenses (base forms in italics):

We will walk to the restaurant.

The kids will swim in the pool this afternoon.

We can show that the verbs following will are in the base form by again using the verb be:

Santa will be upset with Rudolph again.

Present forms of be are impossible after will:

X Santa will are upset with Rudolph again.

X Santa will is upset with Rudolph again.

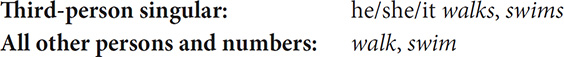

Present Form. With the exception of the verb be, the present is formed in the following manner:

third-person singular = base + s

all other persons and numbers = base

For example:

As noted, the verb be follows a completely different pattern in the present form.

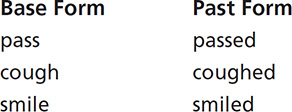

Past Form. There are two ways of forming the past: regular and irregular. The regular verbs form their past by adding -ed or -d to the base form:

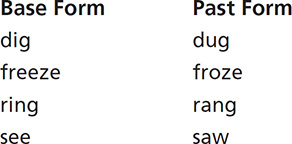

Originally, all irregular verbs formed the past by using a different vowel sound in the past form from the vowel used in the base form. A number of verbs still preserve this ancient way:

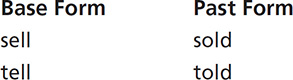

Some irregular verbs became hybrids by keeping their historic vowel changes but adding the regular verb -ed or -d ending:

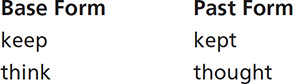

Some verbs have a vowel change but add -t rather than -ed or -d:

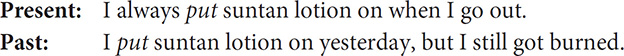

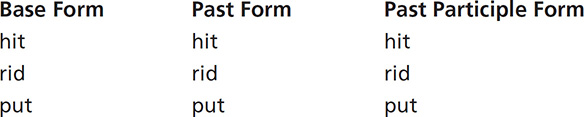

Some one-syllable verbs that end in -t or -d have a past that is exactly the same as the base (or present) form. For example, here is the verb put, first used in the present form and then in the past:

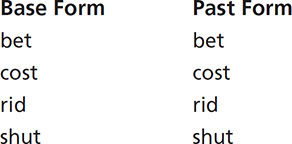

Here are more examples of verbs that follow this pattern:

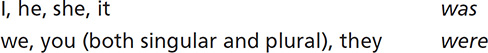

A few verbs have remarkably irregular past forms. The verbs go and be share a peculiar feature: their past forms come from completely different words than their base form comes from. The past of go is went. Went is related historically, not to the verb go, but to the verb wander and the now rare verb wend, as in to wend one’s way. Likewise, was and were, the past forms of the verb be, are from a verb historically unrelated to be. Was and were are doubly exceptional in that they are the only past forms that change to agree with the subject:

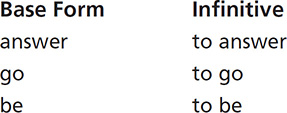

Infinitive Form. The infinitive is also completely regular. It consists of to plus the base form. Here are some examples:

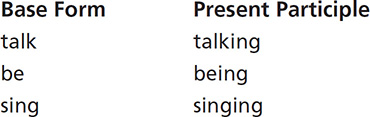

Present Participle Form. The present participle is completely regular in that all present participles are formed by adding -ing onto the base form. Here are some examples:

However, the rules of spelling sometimes cause the present participle to be spelled differently than the base form. For example, the “doubled-consonant rule” will apply to some base forms ending in a single consonant, as seen in hit, hitting; hop, hopping.

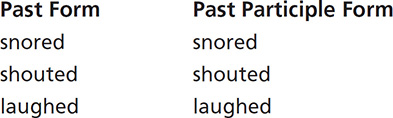

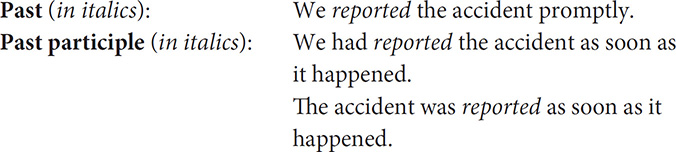

Past Participle Form. There are two kinds of past participles: regular and irregular.

Regular past participles are formed by adding -ed or -d to the base form, just the same way that regular past forms are. The past and past participles of regular verbs are thus identical:

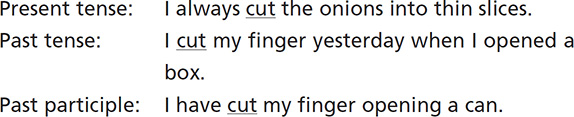

So, how can we tell past verb forms from past participles? Only by the way they are used. Past verb forms are always used by themselves. Past participles can only be used after the helping verbs have or be (in some form), for example:

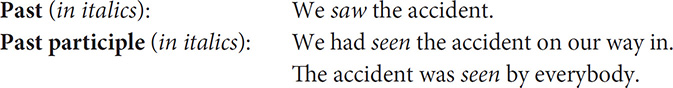

When we use irregular verbs in similar sentences, we can see overt differences between the past and the past participles:

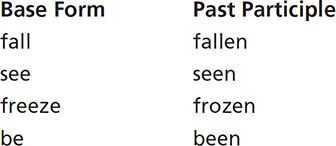

The past participle of irregular verbs historically ended in -en or -n. Many past participles preserve this old pattern, some without a vowel change, some with a vowel change:

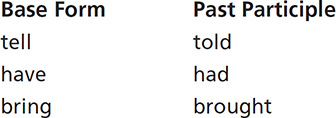

Other irregular verbs have lost the -en or -n and form the past participle in a variety of other ways:

The same group of one-syllable verbs ending in -d or -t whose past forms are identical to the base form also have past participles that do not change. That is, their past participle form is the same as their base and past forms:

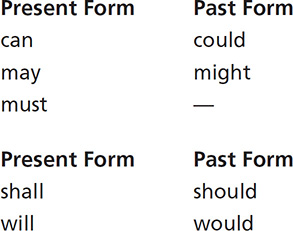

Modal Verbs. Finally, there is an exceptional group of five verbs called modals that doesn’t follow any of the patterns already discussed. For complicated historical reasons, the modals do not have the full range of verb forms. Accordingly, they are sometimes called “defective” verbs. They have both present and past forms (most of them do, anyway) but nothing else. Modals have no base forms, no infinitive forms, no present participle forms, and no past participle forms. Here are the present and past forms of the five modals:

The present forms are themselves highly unusual in that they have no third-person singular -s. For example, we can say:

He can go.

She will leave.

but not

X He cans go.

X She wills leave.

(Trivia item: Notice that must has no past form. It is the only verb in English to have a present form but no past form.)

Modals are helping verbs. They are quite limited in how they can be used. Modals can never be used alone. They can only be used in combination with a following verb in the base form, for example (modals in italics, base verbs in bold):

You can do it.

They must be careful.

You should know better.

Using Verb Forms to Create Meaning

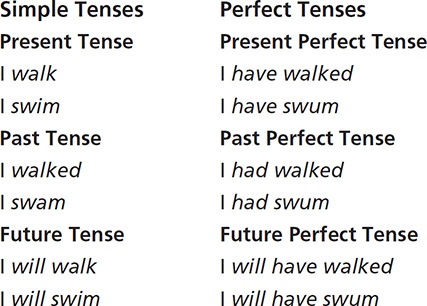

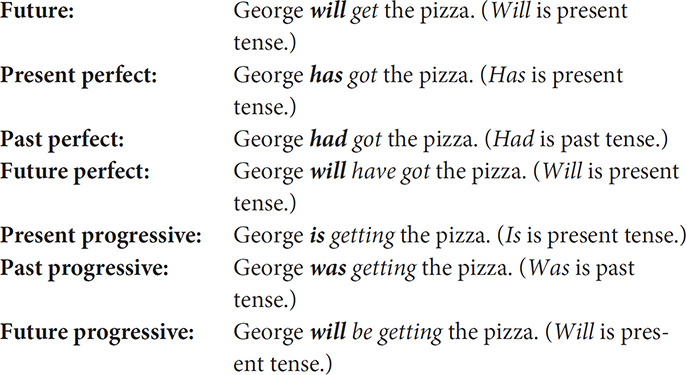

In traditional grammar, English is said to have six tenses. In traditional grammar, there are three simple tenses (present, past, and future) and three perfect tenses (present perfect, past perfect, and future perfect). Here are the six tenses with examples:

We will now discuss in a little more detail how the six tenses are built and what they mean.

Simple Tenses. The simple tenses are not called “simple” because they are easy. Historically, the term simple was used to distinguish the meaning of the three simple tenses from the three perfect tenses. The simple tenses (generally) refer to actions that take place at a single moment in time—at the present time, at a past moment in time, or at a future moment in time. The three perfect tenses, on the other hand, deal with actions that span a period of time.

Present tense. The present tense is the present form of a verb. Despite its name, the present tense form of verbs does not really mean present time. In fact, most action verbs actually sound rather odd when used in the present tense, for example:

? I walk now.

? I run now.

If we want to talk about something happening at the present moment, we do not use the present tense at all; instead, we use what is called the progressive (described in more detail later):

I am walking now.

I am running now.

There are two main uses of the present tense: (1) to make statements of fact and (2) to make generalizations. Here are some examples of statements of fact and generalizations (present tense verbs in italics):

Statement of fact

Two plus two equals four.

Gold dissolves in mercury.

Annapolis is the capital of Maryland.

Generalizations

Liver is disgusting.

The new Lexus is the best-looking car on the road.

Fast-food restaurants exploit their employees.

I shop at Safeway.

Notice the last example: I shop at Safeway. We often use the present tense for generalizations about habitual actions. When we say, “I shop at Safeway,” it does not mean that I am in the process of shopping at Safeway at this moment. It means that it is my custom to shop at Safeway. The sentence is still valid even if I have not stepped foot inside a Safeway store in weeks.

Both statements of fact and generalizations are essentially timeless. Statements of fact sound particularly odd if they are tied to a particular moment. For example, the statement

Two plus two is four now.

makes it sound as though this fact is only temporary—tomorrow, two plus two might be something else. Even statements that are not universally true are still true for an indefinite period of time. For example, the statement

I hate liver.

implies that this statement is valid for the foreseeable future.

One consequence of the fact that English reserves the use of the present tense for timeless statements of facts and generalizations is that technical and scientific writing, which is primarily concerned with statements of facts and generalizations, is normally written in the present tense.

Past tense. The past tense is the past form of the verb. The past tense, obviously, is used to describe events that took place in past time. However, there is more to the use of the past tense than this statement would imply. Because the present tense is preempted for making timeless statements of fact and generalizations, the past tense becomes the primary vehicle for all narration that deals with time-bounded events. For this reason, nearly all stories and novels are written in the past tense.

Future tense. The future tense is formed by the present form of the helping verb will, followed by a verb in its base form, for example (will in italics, base verbs in bold):

The meeting will be tomorrow at four.

I will see you there later.

I will go to Seattle tomorrow.

As you may recall, will is only one of a group of verbs called modals. All of the modals can be used to talk about the future. In this respect, will is no different than the other four modals. The only reason that traditional grammar singled out will from the other modals is that will was the best single modal for translating the Latin future tense into English. However, all of the modals can be used equally as well for talking about the future. Here are examples of the remaining four present tense modals used for the future (modals in italics):

I can go to Seattle tomorrow.

I may go to Seattle tomorrow.

I must go to Seattle tomorrow.

I shall go to Seattle tomorrow.

Modal verbs are anomalous in many ways. For historical reasons, the terms present and past have a different meaning when applied to modals. The terms present and past refer to the historical forms of the modals, not their meaning. Could, for example, is the historical past tense form of can. Might is the historical past tense form of may, and so on. However, the terms present and past do not mean time at all. Even the so-called past tense modals can be used to talk about the future:

I could go to Seattle tomorrow.

I might go to Seattle tomorrow.

I should go to Seattle tomorrow.

I would go to Seattle tomorrow if I could afford it.

In many ways, it makes sense to broaden the meaning of future tense to include all of the modals, not just will.

Perfect Tenses. The perfect tenses consist of the helping verb have in some form followed by a verb in the past participle form. Let us first look at what the term perfect means in traditional grammar. To begin with, perfect does not mean “terrific.” The term perfect comes from the Latin phrase per factus, meaning “completely done” or “completely finished.” The term perfect was used to describe three verb tenses in Latin. They were called perfect, or perfected, tenses because each of the three tenses dealt with actions that spanned a period of time. The action was begun at one time and then completed or finished (get it? perfected) at or before a second time.

The basic idea of the traditional concept of tense is that there is a fundamental division between the time relationships in the three simple tenses and the time relationships in the three perfect tenses.

The action in the simple tenses takes place at a single point or moment in time. In the present tense, it is a present moment in time. In the past tense, it was at a past moment of time. In the future tense, it will be at a future moment of time.

The perfect tenses, on the other hand, deal with actions that span a period of time. The present perfect tense deals with an action that began in the past and continues up to the present time. The past perfect deals with an action that began at a more distant point in the past and ended at a more recent point in the past. The future perfect deals with an action that begins in the present or in the near future and ends by some more distant point of time in the future.

Present perfect tense. The present perfect tense is formed by the present tense of the helping verb have followed by a second verb in the past participle form, which we can summarize as follows:

present perfect = have/has + past participle

We use the present perfect to describe actions that have occurred continuously or repeatedly from some time in the past right up to the present moment (sometimes with the implication that these actions will continue into the future). Here are some examples (present perfect in italics):

Their phone has been busy for half an hour.

The kids have watched cartoons all afternoon.

The choir has sung that hymn a hundred times.

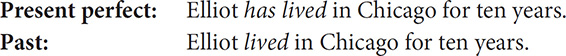

The fundamental difference between the present perfect and the past tense is that the present perfect emphasizes the continual or repeated nature of a past action across a span of time, while the past tense describes a single-event action that is now over and done with. To see the difference, compare the following sentences:

The present perfect sentence tells us two things: (1) that Elliot has lived in Chicago continuously for ten years and (2) that Elliot still lives in Chicago now. The sentence also implies that Elliot will continue to live in Chicago for the foreseeable future. The past tense sentence tells us that while Elliot lived in Chicago for ten years, he does not live in Chicago anymore. His presence in Chicago is over and done with.

A second use of the present perfect describes a recent past event that still affects the present. Here are some examples:

I’m sorry, Ms. Smith has stepped away from her desk for a moment.

Sam has lost his car keys.

In both cases, an event that was begun in the past continues in effect and very much still influences the present moment.

Past perfect tense. The past perfect tense is formed by the past tense of the helping verb have followed by a verb in the past participle form:

past perfect = had + past participle

We use the past perfect when we want to emphasize the fact that a particular event in the past was completed before a more recent past-time event took place. Here are three examples with commentary (past perfect in italics):

I had stepped into the shower just when the phone rang.

In this example, two things happened: (1) the speaker stepped into the shower and (2) the phone rang. The speaker is using the past perfect to emphasize the inconvenient order of the two past-time events.

When we bought the house last year, it had been empty for ten years.

In this example, the past perfect is used to emphasize the fact that the house had been empty for the ten-year period before it was bought.

They’d had a big fight before they broke up.

In this example, the past perfect sequences two events: (1) a big fight and (2) a breakup. Here, the past perfect implies that not only did these two events happen in this order, but there is probably a cause-and-effect connection between them. That is, their big fight may have caused their subsequent breakup.

Future perfect tense. The future perfect tense is formed by the future tense of the helping verb have followed by a verb in the past participle form:

future perfect = will have + past participle

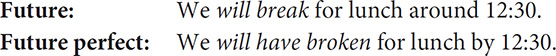

We use the future perfect tense when we want to emphasize the “no-later-than” time of the completion of a future action. Compare the meaning of the following sentences, the first in the future tense, the second in the future perfect tense:

The future tense sentence merely states when some future action will take place. The future perfect sentence puts a “no-later-than” time limit on when the action will have been completed. We could break for lunch at noon or even 11:00, but in any event, we will have broken for lunch no later than 12:30.

Here are some more examples of the future perfect tense:

The train will have left by the time we get to the station.

The paint will have dried by tomorrow morning.

The snowplows will have cleared the roads before we get to the lodge.

The Progressive

The term progressive is used to describe a set of verb constructions that stand apart from the system of six tenses that have already been described. The term aptly describes the main characteristic of the progressive constructions. We use the progressive to emphasize that the action of the verb is in progress or ongoing at a particular moment of time. There are three types of progressives: a present progressive, a past progressive, and a future progressive. All three types of progressive are built in the same way: a form of the helping verb be is followed by a verb in the present participle form. We will now examine each of them in turn.

Present Progressive

The present progressive is formed by the present tense of the verb be followed by a verb in the present participle form:

present progressive = am/are/is + present participle

Here are some examples of sentences using the present progressive (helping verbs in italics, present participles in bold):

I am working on it even as we speak.

We are waiting to hear from the boss.

It’s raining like anything.

We use the present progressive when we want to emphasize that some action is in progress at the present moment.

Past Progressive

The past progressive is formed by the past tense of the verb be followed by a verb in the present participle form:

past progressive = was/were + present participle

Here are some examples of sentences using the past progressive (helping verbs in italics, present participles in bold):

I was working on it when you called.

We were waiting to hear from the boss.

We use the past progressive when we want to emphasize that some action was in process at a moment or period of past time.

Future Progressive

The future progressive is formed by the future tense of the verb be followed by a verb in the present participle form:

future progressive = will be + present participle

Here are some examples of sentences using the future progressive (helping verbs in italics, present participles in bold):

I will be working on it all next week.

It will be raining by the time we get there.

We use the future progressive when we want to emphasize that some action will be in process at some moment or period in the future.

“Tensed” Verbs

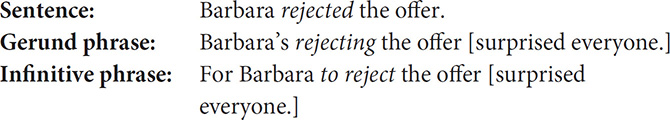

We will end this section on tense with an important generalization about how sentences and clauses are built. Sentences and clauses differ from phrases in one fundamental way: sentences and clauses have verb phrases (or predicates) that begin with a “tensed” verb. A “tensed” verb is a verb in either the present or past tense form. As we will see in Chapter 5, certain types of phrases also contain verb phrases, but their phrases do not have a “tensed” verb. Compare the following examples:

The first example is a sentence because it contains a “tensed” verb—the past tense rejected. While the two phrases contain essentially the same information as the sentence, they are clauses, not sentences, because they do not contain a “tensed” verb. The gerund phrase contains a verb in the present participle form (rejecting), and the infinitive phrase contains a verb in the infinitive form (to reject).

In any noncompounded verb phrase, there can be only one “tensed” verb. If there are multiple verbs in the verb phrase, only the first verb can be “tensed.” Here are examples of the various multiple-verb constructions in italics with the “tensed” verbs in bold:

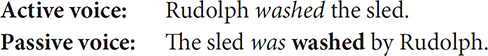

The Passive Voice

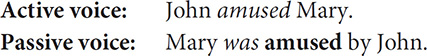

In traditional grammar, all verbs occur in one of two voices: active voice or passive voice. The active voice is the normal state of affairs. Nearly all the sentences that we have examined in this book up to this point have been in the active voice. In the active voice, the subject of a sentence is either the doer of the action (with action verbs) or the topic of the sentence (with linking verbs). In a passive voice sentence, the subject is the recipient of the action. Compare the following sentences:

In the active sentence, Rudolph (the subject) is doing the action of washing. In the corresponding passive sentence, the sled (the subject) is not doing anything. Instead, the sled is the recipient of the action of washing.

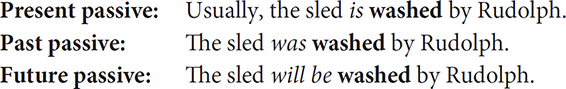

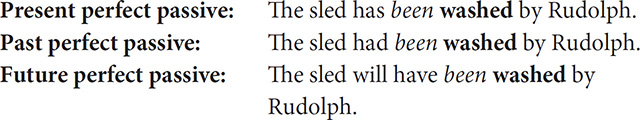

Passives have a unique structure that makes them easily recognizable (once you know what to look for). Passives must contain the helping verb be (in some form) followed by a past participle. The following is the formula for all passive voice sentences:

passive voice = be (in some form) + past participle

The form the helping verb be takes depends on the rest of the sentence. Be can appear in any of the three simple tenses (be in italics, past participles in bold):

Be can appear as the past participle been in the three perfect tenses:

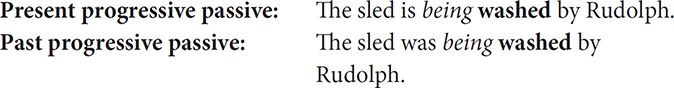

Be can appear as the present participle being in present and past progressive constructions:

The third possibility, the future progressive passive, is actually grammatical, but it is so awkward that it is rarely used:

? The sled will be being washed by Rudolph when Santa comes.

To see why we use the passive, let us take another example of corresponding active and passive voice sentences:

In the active voice sentence, the focus of the sentence is on what the subject, John, did: He amused Mary. In the passive voice sentence, the focus is shifted away from the original subject, John, and instead is refocused on what happened to the original object, Mary: She was amused.

In the passive voice sentence, the original subject can be retained as the object of the preposition by. However, because the whole point of using the passive voice is to shift emphasis onto the original object and away from the original subject, it is quite common to delete the by phrase that contains the original subject. According to one study, about 85 percent of the passive sentences in nonfiction books and articles do not retain the by phrase.

Sometimes we use the passive precisely because we do not know (or care) what the subject of the active sentence is. For example, we would certainly prefer the following passive voice sentence with the by deleted:

My cell phone was made in Taiwan.

to the corresponding active voice version:

Somebody in Taiwan made my cell phone.

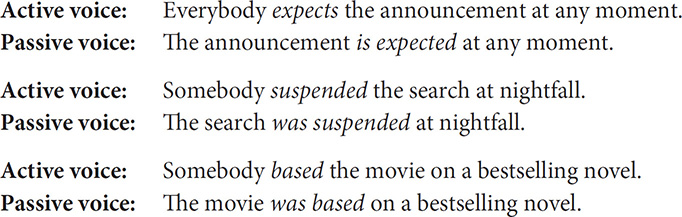

Here are some more active voice sentences with their passive voice counterpoints (verbs in italics, by phrases deleted):

The passive has a certain negative connotation for several reasons. First, the passive can be used evasively, to avoid naming the person actually responsible for an action. When a politician uses the passive sentence “Mistakes were made,” you can be sure that the choice of the passive was deliberate. Second, writers can fall into the habit of using the passive where the active voice would be more vivid and, well, less passive. One of the first lessons in any writing class is making students aware of their needless use of the passive.

Phrasal Verbs

All languages have ways of making new words. English has a rich set of mechanisms for creating new words by compounding verbs with prepositions. The oldest form of verb compounding fuses the preposition onto the beginning of the verb, creating a new verb, for example (prepositions in italics):

bypass

downplay

overthrow

understand

upset

withdraw

Beginning in the Middle Ages, English developed a second way of forming verb compounds—compounding a verb with a following preposition. We will call verb plus preposition compounds phrasal verbs. Over time, phrasal verbs have evolved to become the major source of new verbs in English. The best reference work on phrasal verbs is the Longman Dictionary of Phrasal Verbs. To give you some idea of how common phrasal verbs are, the Longman Dictionary of Phrasal Verbs has more than twelve thousand entries! Phrasal verbs are actually more numerous than nonphrasal verbs.

To get a sense of what phrasal verbs are like, here is a sentence that contains one type of phrasal verb (in italics):

Susan turned down the offer.

The key idea of phrasal verbs is that the verb plus preposition compound acts as a single semantic and grammatical unit. For example, we can paraphrase the meaning of turned down with the single verb rejected:

Susan rejected the offer.

The two sentences, Susan turned down the offer and Susan rejected the offer, mean exactly the same thing. The grammar of the two sentences is also identical. In both cases, the noun phrase the offer is the object of the verb.