7

Subject-Verb Agreement

In order for a sentence to be a sentence, and for a clause to be a clause, the first verb in the sentence and clause must agree in number with the subject. By agree we mean that the number of the verb must match the number of the subject. For example, a singular subject must be paired with the corresponding singular form of the verb, and a plural subject must be paired with the corresponding plural form of the verb, as in the following (subjects in bold, verbs in italics):

The sections in this chapter deal with the three main situations in which writers are most likely to make subject-verb agreement errors:

1. Agreement with lost subjects: This section shows you how to monitor for subject-verb agreement when the subject phrase is so long or complicated that the actual subject can get lost and the verb mistakenly agrees with a word that is not the actual subject, for example:

X The cost of all the repairs we needed to make were more than we could afford.

In this example, the writer has lost track of the subject and has made the verb were agree with the plural noun repairs. The actual subject is the singular noun cost:

The cost of all the repairs we needed to make was more than we could afford.

2. The mysterious case of there is and there was: A surprising number of subject-verb errors involve sentences that begin there is or there was. Part of the problem is that in sentences of this type, the subject actually follows the verb, for example:

X There is usually some leftovers in the freezer.

The verb is singular, but the actual subject is plural, so the verb also needs to be in the plural form:

There are usually some leftovers in the freezer.

3. Agreement with compound subjects: A compound subject is a subject with two noun phrases joined by a coordinating conjunction. This section deals with a number of subject-verb agreement problems posed by compound subjects. The most common problem is the failure to use a plural verb when the compound subjects are joined with and, for example:

X Good planning and careful execution is necessary for success.

The verb is singular, but a compound subject joined by and requires a plural verb:

Good planning and careful execution are necessary for success.

Agreement with Lost Subjects

The most common cause of subject-verb agreement error is when the writer has lost track of what the subject actually is and has made the verb agree with the wrong thing. To a great extent, the causes of this type of error are the length and complexity of the subject noun phrase. The longer and more grammatically complex the subject noun phrase portion of the sentence is, the more likely we are to misidentify the subject.

Part of the reason for this is the way our brain processes linguistic information. Most of us can hold five to seven words verbatim in short-term memory. If the subject noun phrase portion of the sentence is longer than five to seven words (or even fewer words if the subject noun phrase is grammatically complicated), our brains automatically recode the noun phrase in a simplified form. Here is an example:

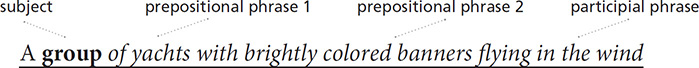

X A group of yachts with brightly colored banners flying in the wind were entering the harbor.

This sentence contains a subject-verb agreement error. The verb were agrees with yachts rather than with the actual subject group. In the research literature on grammatical errors, this type of mistake is so common that it has its own name: the nearest-noun agreement error. When we recode a long and/or complex subject noun phrase into long-term memory, we tend to remember only the semantically strongest noun that is nearest the verb. In the case of the example sentence just given, the semantically strongest noun nearest the verb is yachts.

Here is a psycholinguistic experiment that you can perform at home. Read the example sentence to someone. Then after a minute or so, ask the person what the sentence was about. The odds are very strong that the person will remember the sentence as being about yachts. Very few people will remember the sentence being about a group of yachts.

There are few subject-agreement errors in short sentences because the subject and the verb are either side by side or close together. So, one way to avoid subject-verb agreement errors is to write like third graders with short subject noun phrases. However, because we want to write sentences with adult-level complexity, we need to understand what it is about longer and/or more complex subject noun phrases that makes them hard to monitor for subject-verb agreement.

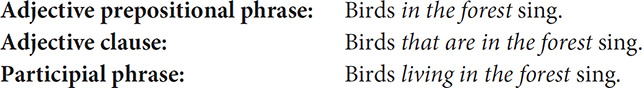

Understanding the mechanisms for expanding the subject noun phrase is the key to gaining control of the nearest-noun agreement error. Subject noun phrases (and all other noun phrases, for that matter) can be expanded in two ways. The first way is relatively trivial: we can put additional adjectives in front of the subject noun. A much more important way of expanding the subject noun phrase is to add postnoun modifiers. Basically, we make subject noun phrases longer and more complex by adding one or more of these three postnoun modifiers: adjective prepositional phrases, adjective clauses, and participial phrases. Here are examples of all three types of postnoun modifiers (in italics) applied to the basic sentence Birds sing:

As you can see, the effect of each of these postnoun modifiers is to push the subject noun birds apart from the verb sing.

When multiple postnoun modifiers are combined, the subject noun and the verb end up at a considerable distance from each other. This is what happened in our original example sentence. The subject group is separated from the verb by two prepositional phrases and a participial phrase:

Consciously checking any sentence for subject-verb agreement always begins with finding the verb and then locating the subject to see that they agree. To check for nearest-noun type subject-verb agreement errors, we need to jump backward from the verb to the actual subject, skipping over all the intervening postnoun modifiers. Our natural tendency is to look at the first noun or pronoun on the left side of the verb for a possible match. This is a mistake. We do not want to cycle back through the sentence from right to left, checking each noun or pronoun as we go for possible subject-verb agreement.

Here is a helpful test for locating the subject when there is a long and/or complex subject noun phrase:

Here is the lost subject test applied to the preceding example sentence:

X A group of yachts with brightly colored banners flying in the wind were entering the harbor.

Begin by locating the verb were. Next, jump back to the beginning of the sentence, ignoring all the intervening nouns. The first eligible noun (also, in this case, the first noun) is group. Unless something remarkable is going on in the sentence, this is going to be the actual subject. Test the verb with that first noun to see if there is valid subject-verb agreement:

X A group were entering the harbor.

In this case, we can see that there is a subject-verb agreement error, which we then correct:

A group was entering the harbor.

The full, corrected sentence reads as follows:

A group of yachts with brightly colored banners flying in the wind was entering the harbor.

Here is the lost subject test applied to a second example:

X The number of accidents caused by drunk drivers dramatically increase at night.

The first step is to identify the verb (in italics):

The number of accidents caused by drunk drivers dramatically increase at night.

The next step is to apply the lost subject test and jump to the first eligible noun or pronoun in the sentence (now also in italics):

The number of accidents caused by drunk drivers dramatically increase at night.

Next, check for subject-verb agreement:

X The number increase at night.

Clearly, there is a subject-verb agreement error that needs to be corrected:

The number of accidents caused by drunk drivers dramatically increases at night.

The lost subject test has one tricky bit. The test identifies the first eligible noun or pronoun in the clause. The reason for this qualification is that often sentences or clauses begin with introductory adverb prepositional phrases that contain nouns or pronouns. The nouns and pronouns in introductory adverb prepositional phrases are not eligible to enter into subject-verb agreement. Here is an example of such a sentence:

X In our last three games, the average margin of our losses have been two points.

The first noun in the sentence is games, the object of the preposition in. Nouns inside prepositional phrases are locked up inside the prepositional phrases and are therefore ineligible for subject-verb agreement. Accordingly, when we apply the lost subject test, we ignore the ineligible noun games and look at the next noun:

X The average margin have been two points.

We have now identified a subject-verb agreement error, which we would correct as follows:

In our last three games, the average margin of our losses has been two points.

In actual practice, introductory adverb prepositional phrases are so easy to recognize that they pose little practical problem in using the lost subject test.

One final point about the lost subject test: despite the fact that all of our examples so far have been sentences, the actual wording of the test is that it applies to clauses as well as to sentences. The term clause is broader than the term sentence. Sentences are just one type of clause—an independent clause. The lost subject test works equally well for subject-verb agreement in dependent clauses as for subject-verb agreement in independent clauses. Here is an example of the lost subject test applied to a dependent clause:

X Harold told them that his cottage in one of the new seaside developments were not damaged in the storm.

To apply the lost subject test, we must jump from the verb were to the first eligible noun or pronoun in its clause. (Remember, clauses are like Gilligan’s Island—you can’t get off.) The first eligible noun in its clause is cottage:

X His cottage were not damaged in the storm.

Clearly, there is a subject-verb agreement error, which we would correct as follows:

His cottage was not damaged in the storm.

The entire sentence would now read this way:

Harold told them that his cottage in one of the new seaside developments was not damaged in the storm.

Summary

The most common cause of subject-verb error is when the verb agrees with the nearest semantically strong noun rather than with the more distant actual subject. Anytime you have a sentence or clause with a long or complicated subject noun phrase, it is probably worth your while to check for lost subject error. Jump from the verb to the first noun in the sentence or clause. Pair that noun up with the verb to see if it makes sense as the subject. The odds are that it is the actual subject. If it does not make a valid subject, work your way across the subject noun phrase from left to right until you find the actual subject. It won’t be far.

The Mysterious Case of There Is and There Was

Nearly every language has a construction called an existential. Existential sentences are used for pointing out the existence of something. In English, existential sentences use the adverb there plus a linking verb (usually a form of be). Here are some examples (there plus linking verbs in italics):

Waiter, there is a fly in my soup.

There was an old woman who lived in a shoe.

There seems to be a problem with my bill.

Houston, there’s a problem.

The grammar of existential sentences is somewhat unusual in that the actual subject follows the verb. Here are the example sentences again, this time with the verbs in italics and the subject nouns in bold:

Waiter, there is a fly in my soup.

There was an old woman who lived in a shoe.

There seems to be a problem with my bill.

Houston, there’s a problem.

We can prove that the nouns following the verbs are actually subjects by making the nouns plural. When we do so, the verbs in italics must change to agree with the changed nouns in bold:

Waiter, there are flies in my soup.

There were some old women who lived in a shoe.

There seem to be some problems with my bill.

Houston, there’re some problems.

One of the authors of this book and his students did a study of subject-verb agreement errors found in the writing of college freshmen. Somewhat to our surprise, a substantial number of subject-verb agreement errors involved existential sentences. Even more surprising, the errors fell into a distinct pattern.

Following are two groups of subject-verb errors involving existential sentences. The first group is representative of more than 98 percent of the errors we found. The second group is representative of a kind of error that made up less than 2 percent of the errors. Look at the two groups, and see if you can figure out what the errors in each group have in common (existential verbs in italics, subjects in bold):

Group A: almost all errors were like this

X There is dozens of books piled on the carpet.

X There was some old dishes that looked usable.

X There seems to be noises coming from the backyard.

X There was still many jobs to be done.

Group B: errors like this were quite uncommon

X There are a big lake on the other side of the mountain.

X There appear to be no solution.

X There were a bright light shining in the trees.

Do you see the pattern? The common error is using a singular verb with a plural subject. The uncommon error is the reverse: using a plural verb with a singular subject. (Didn’t you find the second group to be so odd as to seem almost un-English?)

Clearly, something is going on here. All things being equal, we would expect roughly as many errors with singular subjects as with plural subjects. Some other factor must be intervening to cause the distribution of errors to be so skewed. Something makes it much more likely for us to make a subject-verb agreement error in existential sentences when the subject is plural than when the subject is singular.

The answer seems to be in English speakers’ perception of how existential sentences are built. Apparently, people increasingly think of the existential there not as an adverb but as the actual subject of the sentence. The existential there has become like the pronoun it—an invariant singular that requires a verb with a third-person singular -s. This analysis would explain why errors of plural subjects with singular verbs are so common and the reverse error of singular subjects with plural verbs is so rare. If there is perceived as a singular subject, then all verbs in existential sentences must also be singular to agree, regardless of the number of the noun following the verb.

If this analysis is correct, then we have a conflict between what sounds right in casual, spoken English and what is technically correct in formal, written English. Maybe at some point in the future, existential there will be fully accepted as the grammatical subject of its sentence. But until that happy time, we need to monitor existential sentences for subject-verb agreement.

What we have learned about existential there gives us a considerable advantage in knowing exactly what kind of error to look for:

Following are some sentences containing existential there:

X There is millions of stars in our galaxy.

The noun after the linking verb is millions. Because millions is plural, we must make the verb agree:

There are millions of stars in our galaxy.

X There was several movies that we wanted to see.

The noun after the linking verb is movies. Because movies is plural, we must make the verb agree:

There were several movies that we wanted to see.

X I didn’t like the ending because there was far too many loose ends that were not tied up.

In this sentence, the existential is in the dependent clause there was far too many loose ends. Whether the existential is in an independent clause or in a dependent clause, the rule still holds: look for the noun following the linking verb. In this case, the subject is loose ends. Because the subject is plural, we must change the verb to agree:

I didn’t like the ending because there were far too many loose ends that were not tied up.

X There is an old flashlight and some batteries in the drawer.

This sentence is a little more complicated because we have a compound subject—flashlight and some batteries. We must change the verb to make it agree with the compound subject:

There are an old flashlight and some batteries in the drawer.

Summary

Existential sentences are so prone to subject-verb error that you should monitor each one. Look at the noun following the existential verb to see if it is plural. If it is, check to make sure the verb is in agreement with that plural subject.

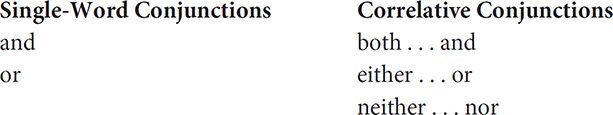

Agreement with Compound Subjects

A compound subject is formed when two (or more) subjects are joined by a coordinating conjunction. The coordinating conjunctions normally used to join subjects are the following:

Following are examples of each (coordinating conjunctions in italics, compound subjects underlined):

Larry and Holly are coming to the meeting.

A pencil or a pen is all that you will need.

Both Donner and Blitzen were really fed up with the fat guy.

Either Fred or Louise is scheduled to be there.

Unfortunately, neither I nor my husband is able to come.

The rules for subject-verb agreement with compound subjects are different, depending on the coordinating conjunction used. For the coordinating conjunction and and the correlative conjunction both . . . and, the compound subject requires a plural verb.

Compound subjects formed with any of the three remaining coordinating conjunctions (or, either . . . or, neither . . . nor) are governed by a more complicated rule: the verb agrees only with the second of the two subjects. Here are some examples (coordinating conjunction- in italics, compound subjects underlined, verbs in bold):

One truck or three cars are all that the ferry can carry at one time.

The verb are agrees with cars, the second (and closer) of the two subjects in the compound subject. Now see what happens when we reverse the two noun phrases in the compound subject:

Three cars or one truck is all that the ferry can carry at one time.

Now the verb is singular to agree with truck.

Either Aunt Sarah or the Smiths are picking you up.

The verb is plural to agree with the plural subject Smiths. Here are the two subject noun phrases reversed:

Either the Smiths or Aunt Sarah is picking you up.

Now the verb is singular to agree with Aunt Sarah.

Neither the banks nor the post office is open today.

The verb is singular to agree with the post office, the second of the two noun phrases. Here are the two subjects reversed:

Neither the post office nor the banks are open today.

Now the verb is plural to agree with banks.

Compound subjects joined with and or the correlative both . . . and would seem to be no-brainers. They always take plural verbs, don’t they? Most of the time they do, but there are three exceptions, which we have labeled “one and the same,” “each and every,” and “bacon and eggs.”

One and the Same

Occasionally, we will use a compound subject in which the two nouns refer to the same person or thing. In this situation, we use a singular verb. Here is an example (compound underlined, verb in italics):

My neighbor and good friend Sally has lived here for years.

In this sentence, my neighbor and good friend Sally are one and the same person. Because there is only one person, the verb is singular.

Here are two more examples:

His pride and joy was a restored Stanley Steamer.

His son and heir is an accountant in Burbank.

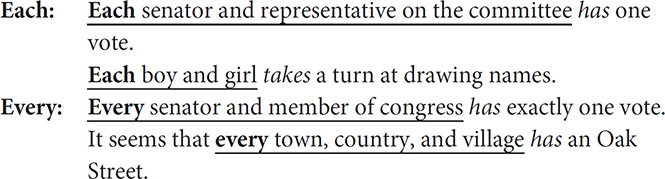

Each and Every

When the modifier each or every is used to modify a compound subject, the verb is singular. Each and every seem to have an implicit paraphrase of each one and every one that requires a singular verb. Here are two examples of each and two examples of every (compound subjects underlined, verb in italics, each and every in bold):

Bacon and Eggs

When compound subjects joined by the coordinating conjunction and form a well-recognized single unit, then they are used with a singular verb. Here are some clear-cut examples of well-recognized single units (compound subjects underlined, verb in italics):

Bacon and eggs is still the standard American breakfast.

Drinking and driving is the major cause of accidents.

The bow and arrow is found in virtually every traditional culture.

Thunder and lightning always scares my dog to death.

The most common source of error in sentences with compound subjects joined with and is writers’ overgeneralizing the bacon and eggs rule. That is, writers tend to think of all compound subjects joined with and as units and thus use a singular verb with all of them.

However, unitary compounds like bacon and eggs are the exception, not the rule. From a purely logical standpoint, one could make a case that all compounds joined with and are units of some sort. It’s too bad the conventions of English grammar are pretty insensitive to logic! The fundamental rule is that compound subjects joined with and require a plural verb. So, unless there is a compelling reason to override the fundamental rule, always use a plural verb with compound subjects joined with and. The following test will help you decide whether or not compound subjects joined with and should be used with singular or plural verbs:

Here are some example sentences, which may or may not be correct as is (compound subjects underlined, verb in italics):

The pencils and some paper is on the desk.

Would you prefer (a) or (b)?

(a) They are on the desk. (They = the pencils and some paper)

(b) It is on the desk. (It = the pencils and some paper)

Here, the choice seems quite clear. The compound subject the pencils and some paper does not seem to be enough of a well-established unit to be replaced by it. Therefore, the sentence needs to be corrected:

The pencils and some paper are on the desk.

Our genetic makeup and our personal experience makes us who we are.

Would you prefer (a) or (b)?

(a) They make us who we are. (They = our genetic makeup and our personal experience)

(b) It makes us who we are. (It = our genetic makeup and our personal experience)

Genetic makeup and personal experience together make a kind of natural unit, but because they are not any kind of a fixed or recognizable phrase, they seems a much better pronoun substitute for the phrase. Accordingly, we need to correct the original sentence:

Our genetic makeup and our personal experience make us who we are.

What we see and what we get is not always the same thing.

Would you prefer (a) or (b)?

(a) They are not always the same thing. (They = what we see and what we get)

(b) It is not always the same thing. (It = what we see and what we get)

In this example, we have a more complicated compound subject that combines two noun clauses. Despite the fact that what we see and what we get are both recognizable phrases, they are not phrases normally yoked together as a single unit. Therefore, they is preferable, so the sentence needs to be corrected:

What we see and what we get are not always the same thing.

Summary

Compound subjects cause a surprising number of subject-verb agreement errors. The single most common error is treating a compound subject joined by and or both . . . and as a single unit that takes a singular verb. Unless the compound subject is a well-established phrase like bacon and eggs, use a plural verb. There are two other main exceptions to this rule:

1. If the compound subject is modified by each or every, then the verb is singular.

2. If the noun phrases joined by the compound refer to one and the same person or thing, then the verb is singular.

If the compound is or, either . . . or, or neither . . . nor, then the verb agrees with the nearest subject.