3:

BETA, OR SPEAK TO ME SOFTLY IN ALGEBRA

THERE is no System in the market, and there are many approaches that work. The generation now in command has had just time enough to learn that at some point any of them can fail. It is a bright generation, so that discovery was damaging to its self-confidence. This generation entered the sixties full of beans. The generation ahead of them on Wall Street had clearly been paralyzed by the memory of the Great Depression. The new generation had moved in with the appropriate lack of inhibitions. The older generation had lacked real, serious security analysis. Now there were ten thousand security analysts. The older generation had relied on country-club information and a few statisticians with green sleeve garters. Now there were computers to screen and filter, to assemble a stunning variety of comparisons and ratios, to do charts and measure relative strength. The financial rewards for the new generation were great, but that was only right and proper for gentlemen and ladies of business-school education, rational intelligence, daring and perception.

Then along came a severe test and took away not only some of the profits, but some of the scientific and self-confident aura of the whole business. The security analysts turned out to be just as wrong as they were right.

Writing in the January-February, 1972, issue of the Financial Analysts Journal, the director of research of a large institution assessed statistically the research which went to institutions. That is research presumably painstaking and not horseback, aimed at a sophisticated audience. The results weren’t much different from the Standard & Poor’s averages, and were summarized as “consistently mediocre.” Some were good, some were bad, and taken all together they weren’t so handsome. (The article may have been a bit unfair in that it was based on published material. The best work of the best security analysts goes unpublished. Analysts are paid indirectly with the commissions of clients, and those clients are quite likely to make up a list—a short list, at that—of the analysts and the firms they want to reward. If an analyst has a bright idea, it is going to go first to his biggest client, and then to his next biggest, and so on. By the time it gets to the nth client, or into print, it has lost much of its value, but it is only from print that surveys and evaluations in the Analysts Journal can be made.)

Not only did the work of the security analysts follow the price of the stock more than the course of reality, but much of the technical apparatus also blew its tubes. The performance of the funds has already been discussed, and in aggregate, the performance of the managers left something to be desired.

The more sensitive and alert money managers were the ones to engage in some self-questioning. Notes from portfolio-manager seminars reveal a change in the tenor of the meetings over a course of four or five years. As the jackets came off and the drinks were poured in the earlier meetings, the questions ran to: All right, what’s hot? What do we buy now? How long have we got? By recent times, the questions had taken on a Kierkegaardian tone—at least so far as this field is concerned—full of doubt and musings. What is a portfolio, as opposed to a list of stocks? Can portfolios be managed as portfolios? Does anyone do it? What is a buy? What is a sale? Which one do you concentrate on? Can anyone outperform anyone else? What is risk?

The last question got asked a lot after some of the portfolios went down 40 percent. After all, why pay a professional to lose 40 percent of your money? Maybe something was wrong with the whole process: assessing where the economy was going, making some sort of market judgment, letting the security analysts scout their stocks, and building the portfolio, with the portfolio manager using his experience, judgment, rational intelligence, intuition, and Fingerspitzgefühl. Maybe that was the wrong way; maybe there was something missing from the process. Maybe that something was risk, the opportunity for loss.

A headlong race to include the risk factor in all the calculations began, even though the professionals for years were accustomed to speak of the downside risk. But maybe you could quantify the risk, so that you wouldn’t have to depend on the portfolio manager’s judgment. Thus was born what came to be called the beta cult, after the Greek letter beta, β. Beta stood for the measurement of market risk through the variability of the rate of return, and thus could be considered a component in capital asset pricing theory. The beta cult gave Wall Street a new jargon to toss around. A dozen Wall Street houses offered beta measurement services, some taking full-page ads in The Wall Street Journal and the New York Times to announce their discoveries. The math and computer people had a quick resurgence, and some senior people growled, as did Lemont Richardson of Booz Allen, “These people with math and computer backgrounds who think they can assign precise degrees of risk to five or six decimal places are nothing but charlatans.”

You have to start somewhere with beta theory, and the usual starting place is with The Theory of Games and Economic Behavior, by John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern of Princeton, published in 1944, which said (among other precepts) that in a game situation, you had to calculate the risk accompanying the course to a particular reward, and to determine the “utility” of that course. In 1952 Harry Markowitz published a seminal article in the Journal of Finance, a version of his doctoral thesis at the University of Chicago. Markowitz showed that diversification could reduce risk, that you could measure the risk by measuring the variability in the rate of return, and that an efficient portfolio was one which provided the highest return for the amount of risk which the portfolio owner was willing to assume. (For this, Markowitz was called “the father of the beta.” He now runs a small arbitrage fund that uses computer techniques but not much beta. At one beta seminar, Markowitz said that he was not the father of the beta but the grandfather, that William Sharp of Stanford was the father.)

The beta enthusiasm had one mildly amusing sidelight. All this statistical work—and the implication that some formula, however sophisticated, can in some way replace the manager—is naturally threatening to the manager. At a seminar five years ago, the Markowitz model, as it is called, was discussed for a whole morning. It was roundly denounced. Markowitz had missed the whole point of diversification; one participant even suggested—and this remains in the mimeographed abstract—that “Markowitz’s books be assembled and burned.” But within five years, brokers—one of them represented at the seminar above—were offering beta studies to their clients as a merchandising come-on.

Beta theory is based on two simple ideas: one, that most stocks and groups of stocks bear a fairly close relationship to the market as a whole, and two, that to get higher rewards, you have to take greater risks. The portfolio’s riskiness is determined by plotting its rate of return—capital gains plus dividends—against the rate of return on a convenient market index, say, Standard & Poor’s 500. The beta coefficient is the measure of volatility, the sensitivity of that rate of return to the market. By definition, the market has a beta of 1.0. So a portfolio of 2.0 would be twice as volatile, on the average; it would go down or up as much as the market. (If you are wondering what happened to alpha, that is the residual influence not related to the market, the vertical axis against which the beta slope is plotted.)

Beta theory has provided a happy hunting ground for the type who love punching computer keyboards and desktop calculators, especially in Academia. When the Financial Analysts Journal did a bibliography on risk and return, it listed—and this in 1968—253 articles and 89 books. Those totals have now gone much higher.

The big push for beta came from the banks, and specifically from the Bank Administration Institute. In the late sixties the money was flowing out of bank trust departments and bank-managed assets and into performance funds and other forms of go-go. The people taking the money away were saying that the swingers were already up 50 and 100 percent, and that the bank-managed money hadn’t moved in ten years. The banks wanted some form of statistic that would say, Sure, the gains are big, but look at the risks.

The Bank Administration Institute put out a report, Measuring the Investment Performance of Pension Funds, which had a considerable impact. Further reports came out of the University of Chicago’s Business School, long a fortress of stock market statistical work, shortly to be renamed Beta U. And beta got a nod in the SEC’s Institutional Investor Study.

All of this work was directed simply at refining comparisons, so that you didn’t take Fund A and compare its record with Fund B without also taking into consideration the volatility—and hence the risks—in each. If the so-called beta revolution is real and not just another statistical fad, then all comparisons in the future will have to contain beta adjustments, mutual funds will disclose their beta assumptions, and incentive fees will be determined by incentive results adjusted by beta.

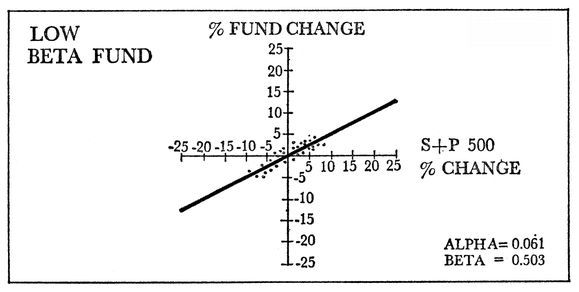

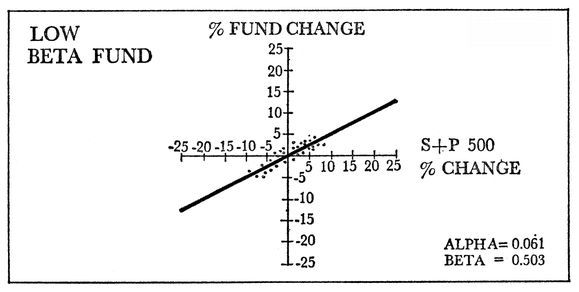

Just so you know what they look like, here are medium, high and low beta funds:

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Source: Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner and Smith, Inc.

Nice and easy, right out of the geometry books, y = a + bx.

There are, as you might have thought, still a lot of disagreements about beta. Does the variability of the rate of return really equal risk? Maybe that is only part of risk. Even if you can describe past portfolios with beta, does that help you build future portfolios? “Price behavior may be people behavior, but people do not behave according to thermodynamic laws,” said a Penn beta researcher, whose paper reported that beta worked on the New York Stock Exchange in wide swings of the market, but seemed to be useless on the American Stock Exchange—back to the drawing board. (Beta proponents say, Sure, there are statistical biases, but they will be worked out imminently). There is no universal time series for beta. Beta might not work in portfolios with a short history. And could not some manager innocent of beta consider downswings as opportunity?

One of the beta theoreticians, after a lot of calculator time, suggested that maybe risk and the opportunity for gain didn’t come out quite as congruent as the first run-throughs suggested. Maybe the opportunities for greatest gain came in emphasizing the moderate-risk course exclusively, and borrowing, if you could, to buy the moderate-risk stocks. That, he suggested, was the most aggressive course possible. Thus did the statisticians arrive at what superachieving children do instinctively, for this is the statistical curve of the ring-toss game charted by David McClelland, the Harvard psychology professor who has pioneered in measuring achievement. In The Achieving Society, McClelland noted that children with low-achievement drives tossed the ring randomly, from any distance, but the high-achievement children tossed from exactly that point that maximized not only their chances of success but their satisfaction from it.

It is a clean, dustless, fluorescently lit world, the beta world, full of the humming of computers. When the beta revolution arrives, you simply decide on the degree of risk you want, and dial that. If you accept the idea, you dial a beta of 1.8 for high risk, or 0.5 for low risk, and go home. So do all the security analysts. “The first step,” said Professor James Lorie of the University of Chicago, “is to give up conventional security analysis. Its occasional triumphs are offset by its occasional disasters and on the average nothing valuable is produced.”

The beta proponents are, by and large, those who believe the stock market is a random walk—touched on in

The Money Game, the freshman course, and earlier here. The random walkers believed that charts were a lot of nonsense because, in my own postulate,

prices have no memory and yesterday has nothing to do with tomorrow. Yet so far, the triumph of beta has been to correlate all the yesterdays. And, according to Chris Welles, author of a notable beta article:

Unlike chemical formulas, investment formulas, if they become widely accepted, tend to self destruct by distorting the very environment from which they are derived . . . Underpinning the asserted need for and utility of such a system is the asserted futility of trying to outperform the market which is itself based on the asserted “efficiency” of the securities market. The market is presumed to be efficient in the sense that, in general, the price of any security at any given time accurately reflects the best available information on that security . . .

Such a degree of efficiency, however, would seem to presuppose a large number of very industrious security analysts. If all security analysts were sent off to school to become metalworkers . . . the efficiency of the stock market would very swiftly decline.

Then there would be a lot of information that wasn’t being used, and the few remaining portfolio managers who signed up for beta could outclass the computers with their specific information.

A couple of years ago there was a flurry in the computer world about relative strength as a technique. All you had to do, by definition, was to stay in the strongest stocks, on the grounds that a stock is going up as long as it’s going up. One of these was George Chestnutt, who sold a service based on momentum, and whose American Investors Fund had risen 398.77 percent from 1959 to 1968. “The machine does all the work,” George said, raising both hands—look, no hands. American Investors Fund went down 40 percent from December 1967 to June 1970. It had momentum, but it had too much beta, not enough alpha, and no soul.

Conscientious fellow that I am, I have been to a number of beta seminars. Here are my notes from one of them:

Any one security can have a substantial positive or negative Alpha, and can have a fairly low Rho. (Rho is the correlation coefficient between the return on the stock and the return on the market.)

At this point I drew a ducky flying through the air.

As we diversify, the portfolio’s Rho tends toward 100% and Alpha tends toward zero.

I went up afterward to talk to our chief instructor. A colleague of mine passed me a note. Simulation does not prove that out, said the note. I drew a little ship on the water.

With Rho near 100% and Alpha near zero, the portfolio’s risk factors depend on its Beta and on the overall market’s average return and standard deviation of returns.

I drew two more duckies, and wondered idly if I could get Teddy Kennedy to take the exam for me.

A questioner in the audience had a question.

Questioner: What happens if in the estimating equation for the Beta, you have misspecified so that you have serial correlation in the residuals?

Moderator: What?

Questioner: What happens if in the estimating equation for the Beta, you have misspecified so that you have serial correlation in the residuals?

Panelist: I think I can handle that. It is not a serious problem.

Questioner: But what if you do?

Panelist: I have written a very complex paper, which I am not sure I understand myself, and I can tell you it is not a serious problem.

Moderator: Does that answer your question?

Questioner: No.

“Whaddya think of the market?” I said.

He looked at me like I was crazy. I had been reading a lot of the literature, so I may have looked a little addled. But I was longing for the good old simple days at Scarsdale Fats’s luncheons, with Scarsdale saying, “What three stocks do you like best?” and the money managers all hustling each other. So I repeated the question. He saw I meant it.

“I have all my money in a savings account,” he said.

Beta theory is going to be a useful tool. At least it is a handy way to describe some of the characteristics of a portfolio. Maybe it is going to be more than that; some people take it very seriously. Maybe all the security analysts and portfolio managers will indeed go off to become metalworkers. If not, beta will be integrated into the existing system, and you will get phone calls like this:

“This stock is selling at thirty-six, and we think it could earn three dollars easy. Keystone is looking at it very hard. The other stocks in the group all sell at multiples of twenty plus. And, oh, yes, it’s got a beta of 1.6. That’s pretty high, but this is a high beta market; everybody’s looking to juice up their betas.”

And before we know it, the accountants will get into the act, and decide that according to generally accepted accounting principles, the stock has either a beta of 0.3 or 1.9, depending on which way you want to look at it, and we will all be back on safe, familiar ground.

Even an elaborate quantification such as beta assumes that Monday will be pretty much like Friday, that the power will still be there for the computers and the stock exchange will be humming along, its thoughts of moving to Dubrovnik merely a passing nightmare. But as that great social philosopher Satchel Paige once said, “Never look behind you, somethin’ might be gainin’ on you.” What could that be?

Well, Watchman, What of the Night? Arthur Burns’s angst; Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird; Prince Valiant and the Protestant Ethic; Work and Its Discontents; Will General Motors Believe in Harmony? Will General Electric Believe in Beauty and Truth? Of the Greening and Blueing, and Cotton Mather and Vince Lombardi and the Growth of Magic; and What Is to Be Done on Monday Morning.

I think it was about five o’clock in the afternoon and the snow was getting worse and I began to ask myself what I was doing in the Pink Elephant Bar in Lordstown, Ohio. The Pink Elephant is on the highway, Route 45, and so is the Seven Mile Inn, and Rod’s Tavern is just off the highway, and the highway is the one that goes by the new $250 million General Motors plant that makes Vegas on the world’s most automated assembly line. My friend Bill and I go up, cold, to these various characters, some of them indeed with mustaches and long hair and sideburns, and there we are: boy social scientists, amateur pollsters. Can we talk to you? Can we buy you a beer? Rolling Rock or Genesee? Do you work in the Vega plant? Is that a good place to work? I mean, would you tell your brother or your son to get a job there? What do you do there? Does your wife work? Do you want another beer? When you get your paycheck, what do you spend it on? Do you spend it in stores, for things, or do you pay it to people—doctors, barbers, plumbers? What do you think of the kids in the plant? The old guys? The blacks? The foremen? The management? Do you want another beer? What do you want to do with your life?

At one point this character in a leather jacket comes up behind us who looks like an old pro football player gone a bit soft—not a tackle; a guard or a linebacker, maybe six-three, two forty-five—and he says, “I heard you talkin’.”

We wait. Some tension in the air, momentarily.

“Air you fum West Vihginyuh?”

We are not from West Virginia. Bill is from Detroit and I am flown from the canyons of Gotham.

“I knew you wasn’t fum here. You talk lahk you’re fum another country.”

Well, yes, I say, it is another country.

“Good, lemme buy you a beer, I lahk to talk to people fum other countries.”

What do you make per hour? Would you rather have overtime or the time off? Is there a generation gap? Would you buy one of the cars you make? What does the union do for you? Why do you work there? What would you rather do? Do you think things are working properly in the country?

You can see all the contemporary social science bits going on: Attitude/Authority? Agree/Disagree Sick Society? Attitude/Work?

Our ambitions are very modest. Bill is doing a story. Maybe he can get another Pulitzer, why not have two? And as for me—why, I am just looking for clues, see, The Future of American Capitalism. I am going through the money-management macro bit in an untraditional way. The man running the money comes into his office, puts on his green eyeshade and his sleeve garters, and says: How goes the world today? And how will it go in six months? A year? But what does he know then? He reads reports and numbers, but what do they tell?

I have just told you about some events in our recent history, in which the system survived and some bright people failed. Are we really then back to normal, a big sigh of relief and business as usual? Or is there Something Else Going On? Maybe the system is changing, maybe our view of reality was distorted all the time. The very bright people were in charge of the government, and making the world safe for democracy, and not only is the world not safe for democracy, it is not even safe in Central Park and downtown Detroit and nobody wants to go out after dark. We put the money into public housing and it turns into disasters such as Pruitt-Igoe in St. Louis, and twenty-two down-towns look like Berlin in 1945. We did put men on the moon, but do we really know how to manage, and how to perform?

The estimable white-haired and pipe-smoking chairman of the Fed, Arthur Burns, comes to report to the Joint Economic Committee of Congress. Clutched in his hand is the Fed’s report for the year, and its promises for the future. The report is all about the Fed’s business, which is money and credit, and the estimable white-haired and pipe-smoking chairman says that the Fed is going to do everything just right: it is not going to let the recovery falter for lack of credit, nor is it going to put out so much credit that we will have another inflationary spiral. But before Burns delivers the report, he has to make some remarks that are not in the report. Maybe “old-fashioned remedies”—that is, those available to Arthur Burns: the levers of credit—can’t do the job. Businessmen aren’t responding in the usual ways. Consumers aren’t responding in the usual ways. “Something has happened to our system of responses. Troubled times have left a psychological mark on people. Americans are living in a troubled world, and they themselves are disturbed.”

What can the matter be? Well, “a long and most unhappy war,” and busing, and the youth vote, and campus disorders, and urban race riots, and the fact that “women also are marching in the streets.” Oh my God, women are marching in the streets.

“If only life would quiet down for a while,” said the chairman of the Fed. The classic economic policies would have a better chance of working if only life would quiet down for a while.

So said the chairman of the Fed, hardly one of your bomb-throwing radicals.

Something has happened to our system of responses. If only life would quiet down for a while.

Poor Arthur Burns, you press the levers and the right things don’t happen, and the problem is life itself. But maybe that is life; maybe that is the way things are going to be from now on. Good God, women marching in the streets, nobody responding in the usual ways. Mindboggling.

So that is one of the reasons I am getting a bit bloated on Rolling Rock beer in the Pink Elephant Bar on Route 45 in Lordstown, Ohio. The economists have made their usual cheery predictions—ah, for the days when Keynes hoped that someday economists would be accorded the status of good dentists—and the analysts are off chasing the new nubile lovelies in a new game of après nous le déluge. But I do not have to show performance weekly or even quarterly, so I can take the time to worry these metaphysical questions that all the money folk will worry about some other time, that have Arthur Burns fingering his Gelusil.

If you simply read the financial pages, you would find no hint of anything different. The type face is the same, the language is the same, and the reports are all of prices: bonds are up, the dollar is down, retail sales are up—sheer minutiae. So everything is back to normal, we had a bad turn there at the end of the sixties, we had to hold our breath a little, but now we can go back to the old stand, Eisenhower is on the throne, the pound is worth a pound and the bells ring out over the land on the Fourth of July. From

Time magazine on the Fourth of July, 1955:

From Franconia Notch, New Hampshire, to San Francisco, California, this week, there was clear and convincing evidence of patience, determination, optimism and faith among the people of the U.S. In the 29 months since Dwight D. Eisenhower moved into the White House, a remarkable change had come over the nation... The national blood pressure and temperature had gone down, the nerve endings had healed . . . In and around the cities, bulldozers and pneumatic drills and rivet guns played an unending symphony of progress . . . at the office coffee breaks, talk was easy and calm, not about the coming war or the coming depression.

Has the symphony of progress come back? Or does Arthur Burns really have something to worry about?

They say, for example, that the good old Protestant Ethic has died away. Whatever happened to work? Doesn’t anybody want to? And growth: the whole system is geared to growth, that is its justification, it works better. What is all this about no-growth, zero population growth, zero economic growth? There is only so much stuff in and on the planet, and at the rate we are using it up in x years there will be no planet. Apocalyptic literature arrives not only on the ecological side but on the cultural side. “The revolution of the twentieth century will take place in the United States,” writes a French critic, Jean-François Revel, “and it has already begun.” “There is a revolution coming,” writes Charles Reich. “It will not be like revolutions of the past. It will originate with the individual and with culture, and it will change the political structure only as its final act . . . this is the revolution of the new generation.”

If any of this is true, we cannot simply go back to where we were. Radical change is very hard for most people to contemplate, and money managers are no different. Their attitude is: Sure, changes, we sell something and we buy something else to fit the changes. You say work is going out of style? We’ll buy play. Here are my six Leisure Time stocks, and let me tell you how long I’ve owned Disney. Money managers operate on the theory of displacement: the framework will be the same, but inside you move things around. My favorite is a gentleman I ran into after I got back from the Vega plant. I told him that one problem among others in certain localities was dope addiction, and at one plant—though the number sounded very high to me—the rate was reported to be 14 percent.

“Well,” he said, “I haven’t owned an auto stock for years. But fourteen percent! Geez, who makes the needles?”

The Chairman was pleased to report sharply higher profits for the year, due to increased sales of the entire line of hospital supply equipment. The reasons for the record profitability, said the Chairman, were Medicare, Medicaid, and the sharply increased use of the company’s new handy throwaway needle by the burgeoning heroin addiction market.

Now it may be that displacement is all we have to consider. Ah, things are out, quality of life is in, back to the countryside; there is a waiting list for ten-speed bicycles, who makes the ten-speed bicycles? Ah, the ecologists are gaining strength, where is our list of water-pollution companies?

That is probably good thinking on the tactical level, but there is also a strategic level, and the strategic level has to consider what the more profound changes are, and in fact it ought to even without the rather parochial justification of buying and selling.

So this is why I am in Lordstown, just as one stop, looking for the sources of Arthur Burns’s angst: Will life quiet down?

In the automobile industry, to consider the parochial side for a moment, rewards and punishments are very tangible, and since the automobile industry is such a fantastic part of America, that would affect us all. General Motors—my God, nobody can comprehend the size of General Motors; it makes one out of every seven manufacturing dollars in the country; its sales are bigger than the budget of any of the fifty states, and of any country in the world except the United States and the Soviet Union. But even General Motors has problems. As Henry Ford II said, the Japanese are waiting in the wings. Someday, he said, they might build all the cars in America. The problem, or one of them, is that imports keep rising, in spite of the theology of Detroit, which always maintained: little cars, fah! Americans won’t buy them; Americans want power, a sex symbol, racing stripes, air scoops for nonexistent air, portholes for nonexistent water; they want to leave two big black tire marks going away from the stoplight, rubber on the road. And the names went with the technology: Firebirds and Thunderbirds, Cougars and Barracudas and Impalas, growrrrr, nothing about driving a handy little car there—so the handy little cars sold were foreign.

Eventually enough handy little cars were sold that the balance of payments continued in its sickening ways and even Washington began to lean on Detroit, and Detroit figured Okay, we’ll build a handy little car. General Motors was not about to have any more of the problems of urban Detroit; it put its $250 million Vega plant in the middle of an Ohio cornfield. And then this work force showed up, the youngest work force around, and look at them—hair down to the shoulder blades, mustaches, bell bottoms, the whole bit; it looks like Berkeley or Harvard Square.

It was a Ford official who wrote the following paragraph, but the same thing applies not only everywhere in the automobile industry but probably in much of factory work. The memo is from an industrial relations man to his superiors, and he is talking about the present and the future. This gentleman is nobody’s fool, and his memo should be in the sociology texts, not in the filing cabinets. (The memo was xeroxed, and a friend of mine got a xerox and xeroxed it again, so I have one, and I guess the UAW has one, because its vice-president Ken Bannon used some of the same phrases word for word in an interview. Communication by samizdat: think what Xerox will do in Russia when it gets going.) The rate of disciplinary cases was going up; turnover was up two and a half times; absenteeism was alarming on Mondays and Fridays. (Hence the useless advice never to buy a car built on a Monday or a Friday. But your dealer will tell you his cars are built only on Tuesdays and Thursdays.) Furthermore, the workers weren’t listening to the foremen and the supervisors. And why?

For many, the traditional motivations of job security, money rewards, and opportunity for personal advancement are proving insufficient. Large numbers of those we hire find factory life so distasteful they quit after only brief exposure to it. The general increase in real wage levels in our economy has afforded more alternatives for satisfying economic needs. Because they are unfamiliar with the harsh economic facts of earlier years, [new workers] have little regard for the consequences if they take a day or two off . . . the traditional work ethic—the concept that hard work is a virtue and a duty—will undergo additional erosion.

General Motors was going to outflank that stuff with the newest, most automated plant; machines would take over a lot of the repetitive jobs; the plant would be in that cornfield in Ohio, near Youngstown, away from all those problems of the, uh, you know, core city. Everything at Lordstown would be made in America, no imported parts, the apogee of American industrialism. The head of Chevrolet buzzed in for a Knute Rockne pep talk. America was going to make the small car, by golly, and that was the end of the elves in the Black Forest and the industrious Yellow Peril in Toyota City, who thought they had been in the small-car business. Planeloads of newsmen were flown in. The line is going to do a hundred cars an hour, lots of it without any people; kachunk goes the machine that pops the wheel rim into the tire, pffft goes the machine that blows up the tire.

So what is all this about trouble in Lordstown? The line is not going at a hundred cars an hour—at least not much of the time—and there are all these characters, all good UAW Local 1112, average age twenty-five, the youngest work force practically anywhere, peace medals, bellbottoms, and hair like Prince Valiant, and the union president is twenty-nine and has a Fu Manchu mustache like the one Joe Namath shaved off, and GM is going up the wall. Where is the productivity? Curtis Cox, the supervisor of standards and methods, is getting apoplectic. “I see foreign cars in the parking lot,” he says. “The owners say they are cheaper. How is this country going to compete?” The GM people practically weep when they think about Japan: all those nice, industrious workers, singing the alma mater in the morning (“Hail to Thee, O Mitsubishi”); whistling on their way to work like the Seven Dwarfs, for God’s sake—never a strike, never a cross word; playing on the company teams; asking the foreman if it is okay to get engaged to this very nice girl as soon as the foreman meets her.

So I ask General Motors quite routinely if I can go see this apogee of American industrialism, say, Tuesday, and General Motors says no, never.

I admit to being a bit stunned. Do they not fly planeloads of people there all the time? Did they not fly alleged same planeloads at the end of the GM strike, together with appropriate refreshment, to watch the first Vega come off the line, with a handout about how the Vega was going to Mrs. Sadie Applepie, library assistant of Huckleberry Finn, Illinois, with a quote all ready from Mrs. Applepie: “Oh, I have been waiting so long for my Vega, I can’t believe it’s finally here, I’m so excited,” did they not? What do they mean, No, not that guy? Who the hell do they think I am, Ralph Nader? I begin thumbing my other notebook that has the number of the pay phone in the hallway of Nader’s boarding house, and it’s off to Lordstown. Because even with plant guards, General Motors is not Russia, and anybody who has graduated from the good ol’ U.S. Army knows how to deal with the lower levels of great bureaucracies. (Where you going with that rake? What rake, sir? That rake. Oh, this rake, the captain, sir, he said take it over there. What captain? The other captain. What other captain? Beats me, lieutenant, they just told me take the rake.)

So we are walking around the plant at Lordstown, all $250 million of it very visible, like an iron-and-steel tropical rain forest with the electric drills screaming like parakeets and the Unimate robot welders bending over the Vegas like big mother birds and the Prince Valiants of Local 1112 zanking away with their new expensive electrical equipment. Vegas grow before your eyes. Beautiful. I recommend it, next time you are taking the Howard Johnson tour across the land of the free.

But what are these cars waiting for repair, marked no high beam signal, dome lite inoperative, no brakes . . . no brakes? no brakes. But what is this on the bulletin board?

Management has experienced serious losses of production due to poor quality workmanship, deliberate restriction of output, failure or refusal to perform job assignments and sabotage.

Efforts to discourage such actions through the normal application of corrective discipline have not been successful. Accordingly, any further misconduct of this type will be considered cause for severe disciplinary measures, including dismissal.

“Corrective discipline”? My God, you can get courtmartialed in this place. They should have an industrial psychologist read the language on the bulletin board. I can hear the Glee Club louder, “Hail to Thee, O Fair Toyota.”

Hi there.

Hi.

What is that?

That’s the window trim.

Is this a good place to work?

Well, it will be, as soon as we get it shaped up.

Would you buy one of these cars?

Sure, if it wasn’t so expensive; it’s a well-engineered little car.

Wouldn’t you rather be out on your own, say, a garage?

Naw, a garage don’t have no benefits.

Say, I don’t want to bother you, two of those Vegas just went by without window trim.

Well, they all go by without somethin’, this line is moving too fast.

That’s productivity, man.

Oh, is that what they call it?

I can give you a few notes of our brilliantly unscientific survey of Lordstown, but they are just that. Our people would rather have had the time off than the overtime. But their wives worked because they needed the extra income. They would tell their brothers to get a job there, and in fact some of them did. Supervisors bugged everybody. Sabotage ? Beer cans welded to the inside of a fender? Well, there might be a few hotheads, but that’s silly, man, the Vega is our bread and butter—the more Vegas they sell, the better for us. If the foremen bugged our people too much, they would get another job somewhere else; they took for granted there would be such a job.

We asked the older types if the young bucks were any different. They said, “Yes. They’re smarter. They don’t put up with what we did.”

Our favorite Prince Valiant haircut said: “I am not going to bust my ass for anybody. I don’t even bust my ass for myself, you know, working around the house.”

But beware. One has to be an epistemological agnostic considering any such report, whether done by journalists or social scientists. How do we know people who talked to us are representative of a work force of ten thousand? Further: journalists and social scientists are verbal, conceptual people. They would probably score very low in electrical repairs around the house; unconsciously they feel: How do they stand it? I wouldn’t like to work here. They did not sleep through senior year in high school with Sister Maria Theresa droning on about Wordsworth and look at the plant as a relief from that. My companion Bill once did a piece about labor for The New York Times Magazine, and some paragraphs were picked up by a social scientist writing a paper. When he subsequently went to do research for a book, properly in awe of all the academic sources, he found the sources quoting him: a second social scientist quoted the first, with appropriate footnotes, and a third quoted the second, with footnotes and notes, and so on—the old beagle pack in cry. This doesn’t mean the job can’t be done, but it takes a large, thorough, well-funded effort, with the appropriate discipline of statistics and all the modes and variants in place.

So all right, it makes sense to have a demurrer for the statistical discipline, but the feeling is there, Something Else Is Going On: the world is not necessarily going to settle back to the Fourth of July, Eisenhower Regency, with life all quieted down. The key phrases are from the xerox of the xerox of the xerox of the confidential memo at Ford; the next key phrases are from the banks of the Charles River. Lordstown is the biggest and bestest example from industrial America, and the Harvard Business School is the West Point of capitalism, or at least so its denizens tell each other, and certainly the place has provided one of the great Old Boy networks of modern times. Let a Business-School-type foul up out there in the world and he need not fear: another Business-School-type will come to his rescue and they will call it merger, or recapitalization, or synergy, or something. I have two straws in the wind to submit from the West Point of capitalism.

Admittedly, these come from an unusual time. Two years before, the greedy little bastids in Investment Management could hardly wait to get going on their first five million, as I said before. Now there is a new crop of greedy little bastids; naturally, the course is still wildly popular, but outside, the Cambodian invasion has been timed neatly with my spring visit. The feeling that all is not well in the world has even penetrated the clouds of greed in my three sections. Around Harvard Square the graffiti was getting political; nobody had written Heloise Loves Abelard in quite a while; instead this flowed in large letters for a third of a block: JOHN HANCOCK WAS A REVOLUTIONARY, NOT AN OBSCENE LIFE INSURANCE SALESMAN. But that, of course, was on the College side of the Charles River, where the life style is different—beards and mustaches and poor-boy clothes, almost as much a uniform as the gray flannel jackets and khaki pants of a generation before. But across the river at the Business School, the budding apparatchiks are coming to class in Brooks Brothers suits and buttondown white shirts, looking like sub-assistant secretaries in the Nixon Administration.

There is no revolutionary chatter in the course catalog at the B School. You find one of the major preoccupations of the catalog is control: “The field of Control deals with the collection, processing, analysis, and use of quantitative information in a business.” In a previous year, when an SDS faction took over University Hall in the College and there was a big bust, the College as an institution seemed very confused, but the Business School had a Contingency Plan in a fat binder with colored index tabs. I had the classes at that time, too, and one B-School faculty member, fearing some Dickensian carmagnole in the streets, Paris, 1789, said of the dissenters: “They’ll never make it to this side of the river. We’ll blow the bridges first.”

So: this is not the Last Bastion, it is not Bob Jones University or even Utah State; it is where they grow the apparatchiks, the technicians who sop up the top spots a generation hence, and if Something Else Is Going On, these types will either lead it or fight it or try to take it over after it gets going.

First straw. Notes from A Class.

The Guest Lecturer has posed a Case. You are running a portfolio of a hundred million dollars. (Baby Stuff.) You are in a competition not unlike the one the Chase Manhattan runs among competing money managers. The worst-performing portfolio managers at the end of a certain time get fired. The best get more money to run, and presumably appropriate rewards.

Company A is a notorious polluter, but its profits are unimpaired. Company B is buying antipollution equipment that will depress its profits for years. Other things being equal, which do you buy, A or B? The Case was not too far from reality. Ralph Nader’s Project on Corporate Responsibility was trying to put some people on the General Motors board, and Harvard owns 305,000 shares of General Motors. Harvard’s treasurer reportedly said he was going to vote for management “because they are our kind of people,” after which both faculty and students generated a furious debate. The Case is not only limited to pollution; the same principles of the social purpose of investment can be applied to defense contractors, the makers of napalm, companies with investments or branches in South Africa, and so on.

All right, you want to achieve performance in your portfolio, and this performance is being measured competitively. It may affect your career. Do you buy Company A, the profitable polluter, or Company B, the unprofitable antipolluter?

Student One: I would try to evaluate the long-term effect . . . because in the long run Company B is going to have a better image.

Student Two: But in the long run you would have lost the account. I think you have to know the wishes of the constituency. If it’s a fund, how do the fundholders feel? What do they want?

(Scattered boos. The class begins to chant, “A or B, A or B”)

Several other students offer comments, all trying to hedge, to keep both the profit and the social purpose.

Student Three: I buy the polluter. (Cheers, then scattered boos) It isn’t the business of a fund manager to make a social decision, or to discriminate between companies on his own ideas of some social purpose. That could be dangerous. If we want to combat pollution, let society vote for it, and have a consensus. I doubt that consumers really want to pay the price. You can’t ask profit-making organizations to subsidize society.

The Radical Student (The Radical Student is only radical by standards of this side of the river, which is to say that he is neatly shaven but is wearing a colored shirt and a tie that is a bit wider than the 1955 width.): Maybe that’s the problem. Everything in this school is geared to the purpose of the corporation, and that purpose is maximized profit.

We ask the Radical Student: “What are the goals of a corporation, if not to maximize profit?”

Silence in the classroom, a rustling of papers. The idea is very confusing.

What are the goals of a corporation, if not to maximize profit?

Not a hand goes up. It is just too hairy a question. We ask it once more. More shuffling, an occasional left wrist shoots out from the cuff with the wrist watch exposed.

The Radical Student: You know the trouble? It’s the way we look at it. We’re concerned with property rights.

At the Law School, say, they talk about civil rights. We’re objective, but maybe objectivity has been overdone. Is our one purpose to measure things?

My second straw is the Resolution. This was, as I said, an emotional time. The Business School voted and passed this, then bought an ad in

The Wall Street Journal to publicize it. The Resolution called for American withdrawal from Southeast Asia, not startling for a student resolution at that time. But this was the Business School, normally heavily Republican, heavily Republican in 1968, and it was the

language juxtaposed to the source that was startling:

We condemn the administration of President Nixon for its view of mankind [its view of mankind?] and the American community which:

1. Perceives the anxiety and turmoil in our midst as the work of “bums” and “effete snobs”;

2. Fails to acknowledge that legitimate doubt exists about the ability of black Americans and other depressed groups to obtain justice;

3. Is unwilling to move for a transformation of American society in accordance with the goals of maximum fulfillment for each human being and harmony between mankind and nature.

Harmony between mankind and nature?

I asked the former dean of admissions what was this about harmony between mankind and nature; when had that crept into the Business School?

“I don’t know,” he said. “I guess it means they’re not going to work for Procter and Gamble and make those dishwasher soaps that don’t dissolve and smother the lakes. They don’t want to work for big companies anyway, or so they say; I’d like to see what they say a couple of years out. The big companies treat them as objects, they say. In the fifties, the guys here all wanted to get to the top of Procter & Gamble. In the sixties it was finance.”

“Last year,” I said, “my classes all wanted to go right to work for a hedge fund. You couldn’t even offer them twenty thousand a year, because they were going to run five million into ten in a year and take twenty percent of the gain. I used to say, ‘Good morning, greedy little bastards.’ ”

“The guys in the fifties,” said the ex-dean, “wanted to run the Big Company, and the guys in the sixties wanted to be Danny Lufkin, make a big bundle by the time you’re forty and run for something.”

“And now?”

“And now, they’re just confused. I’ve never seen such malaise. I don’t think the big companies have gotten the message yet, and maybe the Fortune 500 can run without the Harvard Business School, but I have the feeling something will give on one side or the other.”

More recently, I talked to the same ex-dean, who now teaches a popular course, and asked him what changes there had been. Popular journalism had said that things were “back to normal,” whatever that was. Nader’s Raiders had been swamped with applicants in the emotional summers, and now the young law students were scuffling in the line when the man from Sullivan and Cromwell came to interview. It was said pro bono was over. The law students didn’t even want the social courses any more; they wanted Taxation and Trusts and Corporations. Were the current B-School classes still holding out on the big corporations? Were the big corporations bending at all?

“They’re bending to the extent that they don’t come and interview the wives and tell them they have to fit to corporate life, and move fourteen times in fifteen years,” he said. “But other than that, all you can say is that they’re conscious of some change. As for my students, I think they have an acceptance of corporate life and they’re looking for something inner. I hear a lot about life styles, how they want a non-anxious working life. They don’t want to have what one of them called a dumbbell life, which is to say a blob of work at one end, a blob of home life at the other, and a conduit between, a railroad or a freeway. There’s a lot of stuff about walking on the beach, that the worthy cause is themselves, and that work should fit life, not the other way around, and they talk a lot about intimate relationships, wives, children, and so on.

“So if I had to divide the decades again, I would still say that the fifties produced the corporate man who would rise to the top and die seventeen months after retirement, leaving a beautiful estate; the sixties students wanted a piece of the action; and currently the fantasy is a balanced life—just enough success to include it all; they want to run things but not at any cost; they still want power but now they want love, too.”

Maximum fulfillment for each human being? Harmony between man and nature? That’s not the old Business School. How do you put those things into a balance sheet? Can we operate a corporate society without objectivity, or at least what has passed for objectivity?

I wrote in my notes: Will General Motors believe in the harmony between man and nature? Will General Electric believe in beauty and truth?

It is not, of course, a revolutionary idea in the limited history of capitalism in this country to make something for less than a maximum profit. First of all, profit was not necessarily something that could be controlled; it came like the rain on the crops, between the costs and the market. Moreover, when the bulk of business was family-owned, its purpose was to take care of the family—sons, nephews, and so on—and of the product’s reputation, if it had a reputation of value. So a wagonmaker could simply make a good wagon, and a book publisher could publish an author simply because he wanted to. What we have come to call social purpose was a matter of individual integrity, randomly and haphazardly applied.

But these businesses sold out to bigger ones, and those in turn to bigger ones. Supercurrency! That New York Stock Exchange listing, that broad market with the stock selling at a fancy multiple, the sons of the Founders with Caribbean estates, and the grandsons in their pads all secure to blow their minds with 3K electronic guitar apparatus and not worry about work because the Supercurrency has been salted and peppered into hundreds of trusts so the tax man cannot get it. Only the Supercurrency has to stay Super, the profits have to keep growing, the multiple has to go up, and the accountants can’t do it all.

Multimillion-dollar businesses can’t be run by intuition or seat-of-the-pants engineering. There has to be objectivity, whatever that is, and the continuous quantification of results; we have to have what the course catalog at the school calls “a rigorous and systematic approach,” that is, the collection, processing, analysis, reporting and use of quantitative information. But there is competition, maybe, and the judgment of those crazy crapshooters up in New York; if the earnings go down they will bomb the stock, and then what will our report card as a manager look like?

For our man in the green eyeshade asking how goes the world, how will it go, the harmony between man and nature becomes an important question, and not just a spiritual one.

Nobody is against such harmony. When ecology first crept into the scene, industry seized it as an advertising opportunity; not a filter was bought that the buyer didn’t take an ad about cleaning up the rivers and waters. In fact, at one point someone figured out that more was spent drum-beating about cleanup than on the equipment. Industry began to sense that the public belief that more was better was beginning to fall away. Union Carbide dropped its slogan, There’s a Little Bit of Union Carbide in Everybody’s Home. They wanted you to think of the plastics and the sandwich bags, and instead a Little Bit of Union Carbide meant: the wind’s shifted, here it comes again, shut the doors, close the windows, you know what it cost to have the curtains cleaned last time. President Nixon gave an Ecology Speech, and somebody slipped him a real good quote from T. S. Eliot. “Clean the air! clean the sky! wash the wind!”—that’s what we were going to do, said the President, not realizing that the very same quote went on, “Take stone from stone and wash them ... Wash the stone, wash the bone, wash the brain, wash the soul, wash them, wash them!” Not ecology at all, but the blood of murder in the cathedral.

But while everybody agrees that mankind and nature should live in harmony, few agree on what that means, or how the cost shall be borne. They have not changed the consciousness of the way they think. To paraphrase University of Colorado economist Kenneth Boulding, man has lived through history in a “cowboy economy” with “illimitable plains” and “reckless, exploitative, romantic, and violent behavior.” Consumption was “linear”—that is, materials were extracted from supposed infinite resources, and waste was tossed into infinite dumps. But we are shifting to a “spaceman economy.” The earth is becoming finite, like a closed spaceship; consumption must become “circular”—that is, to conserve what we have, resources must be continuously recycled through the system. Air and water have always been free, and few realize that we are approaching the point in our cowboy ways where we will wrench the earth’s ecology out of shape. In The Closing Circle, biologist-ecologist Barry Commoner writes that we have to reconsider the true value of the conventional capital accumulated by the operation of the economic system: we have not considered the true cost.

The effect of the operation of the system on the value of its biological capital needs to be taken into account in order to obtain a true estimate of the overall wealth-producing capability of the system. The course of environmental deterioration shows that as conventional capital has accumulated, for example in the United States since 1946, the value of the biological capital has declined. Indeed, if the process continues, the biological capital may eventually be driven to the point of total destruction. Since the usefulness of conventional capital in turn depends on the existence of the biological capital—the ecosystem—when the latter is destroyed, the usefulness of the former is also destroyed. Thus despite its apparent prosperity, in reality the system is being driven into bankruptcy. Environmental degradation represents a crucial, potentially fatal, hidden factor in the operation of the economic system.

So we do not even have a true picture of how well we have done. This parallels the arguments of the British economist Ezra Mishan. If a wage earner dies sooner because of exposure to mercury, radiation and DDT, but doesn’t have extra medical bills, is there not still the cost of the lost earnings from the extra years? They have to be assigned a value, even if the human anguish of the missing years is ignored.

According to Commoner, intense environmental pollution in the United States has come with the technological transformation of the productive system since World War II. Production based on the new technologies has been more profitable than the older technologies they replaced; that is, the newer, more polluting techniques yield higher profits. We could, of course, survive with new technologies, new systems to return sewage and garbage to the soil, retire land from cultivation, replace synthetic pesticides with biological ones, recycle usable materials, and cut down the uses of power. That would cost about six hundred billion, or a quarter of our current capital plant.

Placed in the kind of terms used in the analysts’ societies, this debt-to-nature means there is suddenly a liability on the balance sheet we didn’t know was there. It must have been in the footnotes, in fine print. We have been very profitable, but the plant is falling down. We can build a new plant, but we are going to have to amortize the charges against earnings for a long time.

Ah, but then we have a spanking new plant. Isn’t that good? Not in the terms, necessarily, that we have been used to considering as good. Of course, if we survive, that’s good. And perhaps even prevent life from getting more noxious, that’s good. But we have been measuring good as profitable. New capital expenditures are—at some point—supposed to increase the profits. That is why the class is so confused when asked what the purpose of the corporation is. Good is profitable; profitable is new technology; new technology has been pollutive, and profitable. Killing whales is very profitable until the day when there are no more whales, because we have only been amortizing the ships and the radar and the depth charges and harpoons. We haven’t amortized the whales, and anyway, how do you replace whales?

But the debt to nature, paid, does not increase either productivity or profitability. Thus, probably the corporation is not going to pay up unless the society compels it, induces it, inveigles it, or brings it about in some other way. The vision of good is simply too far removed from the vision of what has been perfectly good in the hundreds of years of cowboy economics.

This is going to be true not just for the United States and not just for capitalism. The Cellulose, Paper and Carton Administration of the Ministry of Timber, Paper, and Woodworking in the U.S.S.R. is going to have its problems, too. It has its quotas, and the boys at the Ministry get their satisfactions from churning out the stuff, and ecology freaks are everywhere. This is from Professor Marshall Goldman’s account of the pollution of Lake Baikal, the world’s oldest lake and largest body of fresh water by volume. The manager of the plant at Bratsk is asked why a new waste filter has not been installed. Says he: “It’s expensive. The Ministry of Timber, Paper and Woodworking is trying to invest as few funds as possible in the construction of paper and timber enterprises in order to make possible the attainment of good indices per ruble of capital investment. These indices are being achieved by the refusal to build purification installations.”

The finite-earth argument leads almost inexorably to a call for an end to growth, both in population and industrial output. Growth in industrial output is one of the justifications for both capitalism and socialism, each to each. When Khrushchev talked about burying us, he was bragging about increases in industrial production. Increases in our Gross National Product have been hailed as the triumph of our system. (Leave aside for a moment what GNP measures. It does measure only quantity; so if everybody goes and buys triple locks for their doors because crime has increased so much, the GNP goes up, though the quality of life may have gone down. There are those who believe we should attempt to measure such quality.)

The most dramatic assault on growth came from a group at MIT headed by Dennis Meadows, which built a mathematical model of the world system with the interrelationships of population, food supply, natural resources, pollution, and industrial production. The Meadows group produced a doomsday equation: the world is out of business in less than a century, unless the “will” is generated to begin “a controlled, orderly transition from growth to global equilibrium.” Even new technologies, such as nuclear power sources, said the group, wouldn’t help much. The team doubled the resources and assumed that recycling cut the demand to one-fourth; even optimistic estimates didn’t put the day of doom off longer than 2100. We are going to stop growing one way or the other, said the group, the other being the collapse of the industrial base through depleted resources, and then lack of food and medical services.

This report did not lack for critics. One economist said it was “Malthus, with lights and a computer”; others said the base was too skimpy for the assumptions, and that future science and future technology were unknown. If you had assumed our population growth in 1880 without the automobile, you could have assumed asphyxiation by horse manure. If materials were going to become visibly scarce, would not the prices begin to anticipate scarcity? And would not new materials and new power sources be developed? The representatives of less developed countries who considered the report at a Smithsonian symposium were particularly alarmed, because freezing growth without some sort of worldly distribution of income would keep them at their current levels. The poorer nations, said the Indian ambassador, would “slide down to starvation.” At another international conference, the Malaysians said: “Some of us would rather see smoke coming out of a factory and men employed than no factory,” and “We are not concerned with pollution but with existence.”

At the laissez-faire end of the spectrum, economists like the University of Chicago’s Milton Friedman think that in arguments over social issues “there is a strong tendency for people to substitute their own values for the values of others.” The current pollution concern is “an upper-income demand—the high-income people want to get the low-income people to pay for something that the high-income people value ... people move from the clear, clean countryside to the polluted cities—not the other way around—because the advantages of the city outweigh the disadvantages.” Left alone, “people are more likely to act in their own interests, to evaluate the costs and benefits of their own activities.”

It is, of course, hard to legislate changes in consciousness. But most economists are unwilling to give up growth as a goal. World population is certain to grow for many years to come, an extra billion between 1960 and 1975, three more billion in the next quarter-century. Even if that rate of increase is slowed, you need growth just to keep pace. In a world of no growth but more people, you only accomplish one person’s well-being, or one nation’s, at the expense of another. That is the kind of redistribution of wealth we had before there was any surplus wealth to compound, when people in skins hit each other over the head with mastodon thighbones to accomplish the redistribution. Presumably we have only recently outgrown such activity, and the record of social maturity is not a record anybody would trust to the application of economic problems. So the doomsday equations have at least the virtue of getting people to think about the problems of a finite earth; it will take long enough to do something about it anyway.

It is from the increments that poverty is alleviated and the goals of the society met. If there are social problems—such as pollution—that can’t be met by the market mechanism, they can be met by a pricing system: penalizing the polluter, let us say, or giving a tax incentive to achieve the desired end. This is not a net gain to growth in the traditional ways we have measured growth, because the stimulus from investments in pollution control is outweighed by the price rise in the end product, hence a damper on total demand. A study prepared for the Council on Environmental Quality, a government office, indicated this could be done for a small percentage of annual GNP, less than 1 percent, for air and water.

What is the impact of all of this on the man in the green eyeshade considering how goes the world? In the short run—and the short run is all that is considered by many of the men in green eyeshades—he can continue to play the game of displacement: who makes the needles. (If the Meadows model were to be true, and we were to be closer to doomsday, and the pricing mechanism were left alone, the man in the green eyeshade could make incredible killings by buying up commodities on the eve of their disappearance.) But in the longer run, the demand for social purposes, whether in pollution control or health, education and welfare, is going to come out of the savings flow. (Institutional Investor magazine polled forty-one of the nation’s leading academic, governmental, and business economists, and two-thirds of them believed that (a) growth should continue, with a change in priorities, and (b) that additional “income-wealth redistribution is required.”) If the government borrows in the capital markets to deliver, it tips the balance we discussed in an earlier chapter. If it raises taxes to deliver, that comes at least partially out of profits. And if it, in effect, prints the money to deliver, then inflation also will cut into profits. As is often said in this sort of discussion, there ain’t no such thing as a free lunch.

There are some items to be balanced against this. One is the value of the compound in a trillion-dollar economy. One is the growing role of services in the economy; by 1980 the Department of Labor says more will be employed in services than in manufacturing. Services are nonpollutive, but the productivity curve also begins to flatten because there are no economies of scale from doctors, teachers, barbers and string quartets.

The man in the green eyeshade is a capitalist and a manager : “The capitalist and managerial classes may see,” writes Robert Heilbroner in Between Capitalism and Socialism, “the nature and nearness of the ecological crisis . . . and may come to accept a smaller share of the national surplus simply because they recognize that there is no alternative.”

Some conclusions are inescapable. Even if the ecological crisis is overstated and far away, even if social problems can be solved with the existing mechanism—both of those points arguable—the consensus is moving away from the market as decision-maker and from the business society. As soon as you get all the articulation of “goals” and “priorities,” you are moving from decision-making by market to decision-making by political philosophy. (This is an idea developed by Daniel Bell both in The End of Ideology and in The Post-Industrial State, and by others.) “What’s good for General Motors is good for the country,” said Charley Wilson, one of Eisenhower’s businessmen Cabinet members. It would be interesting to see, year by year, what percentage of the people agree with that, and to watch the change.

So the money manager in the metaphorical green eyeshade will no longer be operating in a world where the market determines totally what is produced (and induced), nor in a society run by business decisions. Capital is scarcer and profits are thinner. He is still looking for three stocks that will double, but the range of his options is less. He has always looked not just at profits, E, but at the rate of change in estimated profits, E + ΔE, and in the long run—the broad run, the macro scene, whatever—his expectations are diminished.

Open-ended expectations are an integral part of the markets we have grown up to know. Without them, the calculators can calculate the rates of return, and everybody can be on their way home at 10:05 A.M. to work on their Leisure Time, or more likely, to attend some committee meeting that will be devised to take up the remaining hours. The expectations are what Keynes called “animal spirits”:

A large proportion of our positive activities depend on spontaneous optimism rather than on a mathematical expectation, whether moral or hedonistic or economic. Most, probably, of our decisions to do something positive, the full consequences of which will be drawn out over many days to come, can only be taken as a result of animal spirits—of a spontaneous urge to action rather than inaction, and not as the outcome of a weighted average of quantitative benefits multipled by quantitative probabilities ... thus if the animal spirits are dimmed and the spontaneous optimism falters, leaving us to depend on nothing but a mathematical expectation, enterprise will fade and die—though fears of loss may have a basis no more reasonable than hopes of profit had before . . . individual initiative will only be adequate when reasonable calculation is supplemented and supported by animal spirits, so that the thought of ultimate loss which often overtakes pioneers, as experience undoubtedly tells us and them, is put aside as a healthy man puts aside the expectation of death.

None of this will happen tomorrow, and it was also Keynes who said that “in the long run we are all dead” and that the conventions by which we operated were a succession of short terms—those looking at the long run did so at their own peril. We have a marketplace in which it is possible to float all the services as well as the manufactures, and so probably many happy hours of playing with the displacements await our men. But if we are to give up the “illimitable plains” of the “cowboy economy,” the new and smaller horizon is going to affect our ability to believe that we can compound and extrapolate with impunity, that the three hot ones we heard about at lunch today can go from 5 to 100. We have already lost our gunslingers, a phrase I once applied to some of our citizens, and if our Big Sky goes we will have to give up some of our fantasies. But they always were fantasies anyway, and maybe there are other energies to make our wheels spin.

Having thus dispatched the spirit of capitalism, let us see what we can do with the Protestant Ethic. That phrase describes a devotion to thrift and industry, postponed pleasure and hard work, the hustle as approved by the Lord. It accompanied the Puritan temper, a rather forbidding and pleasure-shy view of life, and is aptly described in the confidential Ford memo together with the complaint that it is disappearing: “the traditional work ethic—the concept that hard work is a virtue and a duty—will undergo additional erosion.” (You have already seen the seeds of conflict, because if Prince Valiant at the Pink Elephant says, “I am not going to bust my ass for anybody, I don’t even bust my ass for myself,” it is safe to say he does not believe that “hard work is a virtue and a duty.”)

We may keep using the phrase Protestant Ethic—everybody does—but for the record we should now split Protestant from Ethic. We call it that because Max Weber called it that in one of the classic works of political economics, and the sociologists and political economists are still sending students to the paperback stores for Max Weber, and not just for the Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. The textile families of northern France—Catholics all—sent letters to their sons, and to each other, that could have gone right into Die protestantische Ethik. Weber did not say, of course, that Protestantism was the sole cause of capitalism. In his commentary on Weber, Julien Freund says that the Protestant Ethic was at least in part a reaction against Marx’s solely economic motive. Embryo capitalism had existed in other societies—Babylonian, Indian, Chinese, and Roman—but the “spirit” of capitalism only developed with the mystery-less, magic-free character of Protestantism, with its rationality and rationalization. (This will come up again in a moment in the counter-culture’s objections.) The accompanying asceticism of Protestantism said that you worked hard in your calling to succeed—a sign of election by God—but did not spend the wealth created, because only sobriety pleased God. “Thus the Puritan came to accumulate capital without cease.” Even Keynes’s assumptions in Essays in Persuasion seem to be based on a kind of Protestant society, where wealth increases because the margin between production and consumption increases.

Talk about industry, thrift and the way to salvation, the Protestant Ethic has found its happiest current home in a very non-Protestant country—at least in name—Japan. A while back, on a visit, I would ask people in Japan: How much vacation do you take a year? And the answers would come back: two days, one day, three days. Why so little? Well, if you work on your vacation you get paid more, and the beaches are too crowded anyway. And I remember sitting with the translator of my own book, himself a distinguished director of the Bank of Japan, everybody cross-legged, a sliver of raw fish poised between his chopsticks, a garden scene framed perfectly by the door.

“In the 1960’s,” said the honorable director, “our total output passed Italy, France, Germany, and England; at this rate we will pass the U.S.S.R. in 1979. How? Our people save twenty percent of their wages. No other country saves so much. In the U.S. it is closer to six percent.”

It is indeed, and when sour years come and the people clutch a little and the savings rate goes up to 8 percent, the President gathers his economic advisers to Camp David and wants to know what the hell is wrong with the Consumer, how do we get him to loosen up?

“Of course,” said the director’s research assistant, “we will not pass the United States until ...” and everybody stopped talking because that was not courteous.

“Sometime in the 1990’s,” said the director, “and many things could happen by then: we have social overhead building up.”

“But we have done this without resources, without oil, without surplus food,” said the assistant, “with industry and thrift, industry and thrift.”

(The voices in Osaka rise to haunt the finite-earth model builders, in the morning alma mater:

“For the building of a new Japan

Let’s put our strength and minds together

Doing our best to promote production

Sending our goods to the people of the world,

Endlessly and continuously,

Like water gushing from a fountain.

Grow, industry, grow, grow, grow!

Harmony and Sincerity!

Matsushita Electric! Matsushita Electric!”)

Industry and thrift, dedication and devotion; you could imagine the United States without them, but not without the mythology and ethic behind them. What is at stake is the happiness of Arthur Burns, whether we will always have a cost-push inflation, whether we stay Nation Number One like President Nixon wanted, and what happened to our dreams of becoming rich. Nothing unambitious about that, either.

Once again, the Ford memo:

For many, the traditional motivations of job security, money reward, and opportunity for personal advancement are proving insufficient.

Insufficient! Security, money, and personal advancement? Do you know what we have to throw off to get to this point?

I give you the honorable Cotton Mather:

There are Two Callings to be minded by All Christians. Every Christian hath a GENERAL CALLING which is to Serve the Lord Jesus Christ and Save his own Soul . . . and every Christian hath also a PERSONAL CALLING or a certain Particular Employment by which his Usefulness in his Neighborhood is Distinguished . . . a Christian at his Two Callings is a man in a Boat, Rowing for Heaven; if he mind but one of his Callings, be it which it will, he pulls the Oar but on one side of the Boat, and will make but a poor dispatch to the Shoar of Eternal Blessedness . . . every Christian should have some Special Business . . . so he may Glorify God, by doing Good for others, and getting of Good for himself... to be without a Calling, as tis against the Fourth Commandment, so tis against the Eighth, which bids men seek for themselves a comfortable Subsistence . . . [if he follow no calling] . . . a man is Impious toward God, Unrighteous toward his family, toward his Neighborhood, toward the Commonwealth . . . it is not enough that a Christian have an Occupation; but he must mind it, and give a Good Account, with Diligence . . .

and so on to

Poor Richard’s Almanac: A sleeping fox catches no poultry; one day is worth two tomorrows; diligence is the mother of good luck; early to bed and early to rise provides a man with job security, money reward and opportunity for personal advancement.

The extension of this ethic into industrial America was a real triumph. The Ford vice-president has a distinct problem: it is very hard to think of working on the line as a Calling. Cotton Mather’s listeners did not take this lightly, nor did he: “Man and his Posterity will Gain but little, by a Calling whereto God hath not Called him”; a Calling was to be

Agreeable as well as

Allowable. It does make work seem softer and more important to have been prayed for:

It is a wonderful Inconvenience for a man to have a Calling that won’t Agree with him. See to it, O Parents, that when you chuse Callings for your Children, you wisely consult their Capacities and their Inclinations; lest you Ruine them. And, Oh! cry mightily to God, by Prayer, yea with Fasting and Prayer, for His Direction when you are to resolve upon a matter of such considerable consequence. But, O Children, you should also be Thoughtful and Prayerful, when you are going to fix upon your Callings; and above all propose deliberately Right Ends unto your selves in what you do.

It is a bit hard to imagine, then: “Ma, I have fasted and prayed and sought the wisdom of God. I know my Calling, and I am going to work on the line at Ford, $4.57 an hour, as an assembler.”

It seems almost simplistic to suggest, but you are more likely to bust your ass when everybody has been fasting and praying for you and what you are doing and your oar of the boat on the way to the Shoar of Eternal Blessedness than if none of those things are true, and if you are Ford, you have an extra problem if that spirit has departed.