Civilization and Mural Painting

In his journal Delacroix explicitly mocked the idea of modernity as the culmination of civilization, positing instead that civilization and barbarism exist in an unpredictable dialectic and that contemporary notions of progress were illusory. In his mural paintings he avoided any explicit reference to modernity, focusing instead on antique subjects that could only be related allegorically to contemporary society. His first major treatment of the theme of civilization, in the Deputies’ Library of the Bourbon Palace, provided extended philosophical reflections on civilization and barbarism by exploring the narratives of his historical and literary sources. Commentary on his own society was never far away, as many of his subjects offered political and moral allegories. Subsequent murals, even though they continued to explore the idea of civilization, separated the past more completely from the present. I argue here that in the later work the function of mural painting changed for Delacroix. He focused more exclusively on the artistic problems it posed, engaging in a competition with past masters and emphasizing the decorative qualities of his art in order to provide a kind of escape or release from the modern world.

Delacroix’s cycle of twenty-two murals in the Deputies’ Library (fig. 7) is one of the supreme artistic achievements of nineteenth-century France and indeed one of the great decorative cycles in the history of art. The setting for Delacroix’s work is itself magnificent. The library is a long, relatively narrow space arranged along a main axis that runs north to south. Its plan comprises a single file of five square bays framed at each end by a hemicycle. Tall, grand arches define the individual bays and carry ceilings that loom high above visitors to the room. Each bay is surmounted by a cupola, within which four pendentives, framed by gilded stucco moldings, rise to a circular central field. In addition to the twenty pictures in the pendentives of the five bays, a single, enormous painting fills the ceiling of each hemicycle. The original design of the library provided for natural light to enter the room through skylights installed in the ceilings of the hemicycles and from the deep clerestory windows set high within the arches on the east and west sides of the bays. Later additions to the palace blocked the eastern windows, but those to the west still function. The natural lighting not only illuminates the ceiling paintings but also filters down to the lower stories, where it plays over rows of leather-bound books shelved in the oak bookcases lining the walls.

FIG. 7 Library of the Chamber of Deputies. Palais Bourbon, Paris.

The fame of the murals has been limited by their inaccessibility: since their completion the building has served as the seat of various legislative bodies (today the National Assembly) and can be visited only with difficulty. For Delacroix, however, the site could hardly have appeared more prestigious. The palace had been redesigned in the years around 1830 by Jules de Joly and housed the Chamber of Deputies under Louis-Philippe.1 Like Michelangelo, Raphael, Rubens, or Le Brun, Delacroix was decorating the halls of power, where his art would be viewed by the audience that mattered most to him: the elite society of nineteenth-century France. He surely compared the library in his own mind to the Sistine Chapel and the Stanza della Segnatura; it is no accident that the murals are filled with allusions to Raphael. Delacroix derived some of his subjects, such as Alexander and the poems of Homer, directly from the Renaissance master, while in other places he drew on individual motifs.2

The murals have a long and complex genesis that I summarize here primarily to demonstrate how greatly Delacroix’s conception of the ceiling changed as he worked on it. As part of the remodeling of the Bourbon Palace, Delacroix had successfully completed mural decorations for the new Salon of the King in 1838 and received indications that he was in line for more work in the building.3 In a letter to his childhood friend Jean-Charles Rivet he announced that he was pursuing “two or three intrigues” in order to paint “a few feet of wall.” He doubted the commission would bring him much money, but it “would satisfy the need to work on a grand scale, which becomes excessive once one has tasted it.”4 His display of ambition—offered with a slight swagger—suggests something of the prestige associated with mural painting.

Delacroix submitted to the government an extremely ambitious proposal to decorate three rooms. For the entrance hall he envisioned murals devoted to “the power of France, especially in its civilizing sense.” The room’s long, narrow ceiling necessitated, according to the artist, a battle painting, and he selected as his subject Charles Martel defeating the Moors on the fields of Poitiers “at the moment when they were in the heart of France and on the verge of toppling our nationality.” The battle “saved our Christian and Western civilization, and probably that of all of Europe, with our laws, our customs, etc.” For the spaces under the arches that supported the ceiling, Delacroix proposed to do six paintings separated by caryatids “representing the peoples subdued by our arms or civilized by our laws.” The subjects of the paintings “would tend to represent not so much feats that are glorious for our armies as actions that have spread the moral influence of France.” The subjects were:

1.Charlemagne receiving homage from the emperors of the Orient, and the sciences and arts introduced into France under his auspices.

2.The conquest of Italy by Charles VIII. Delacroix noted, “We owe to these possibly reckless conquests the renaissance of letters. The introduction of the mulberry tree into France dates from this moment.”

3.Clovis defeating the Romans [sic] at Tolbiac, which was “the first step toward a unified French nationality.”

4.Louis XIV receiving the submission of the doge of Genoa, which “expressed the apogee of the French influence in Europe.”

5.Egypt subdued: “France is the first to return to the origins of all civilization, in this ancient cradle of knowledge. Moreover, she leaves in this land, which had become once again barbarous after so many centuries, the fecund seeds of emancipation, to which all the peoples of the Orient are called.”

6.The conquest of Algeria. “Revenge for an affront to our dignity will have changed the face of North Africa and established the rule of our laws in place of a brutal despotism.”

Delacroix proposed finally that, if funds permitted, he could produce four more paintings of unspecified historical events from French history on a remaining wall.5

The patriotic, even jingoist, tone of this proposal stands out today: the confidence in French moral superiority, the celebration of military conquest as a medium of cultural exchange, the Orient and Islam as the West’s eternal foes, the suggestion that French colonial endeavors in North Africa were unambiguously justified, righteous, and beneficial to the conquered. This sort of rhetoric was anything but unusual for such commissions, but the embrace of national military conquest, both past and present, deserves emphasis. As a lifelong admirer of Bonaparte, Delacroix could be expected to see the Egyptian campaign as a success and to accept “emancipation” as its motivation, but other subjects seem hastily formulated. How much longer, in 1838, could the famous incident in which the dey of Algiers swatted the French consul to the city serve as a pretext for the full-scale war and colonization in Algeria? Delacroix himself would soon have doubts about colonialism in North Africa (see chapter 3). The older subjects also posed problems. Had Charles VIII’s campaign in Italy really been a success, and who had influenced whom in this war? Perhaps Delacroix wished to secure the commission with the same popular language of national conquest that had dominated large-scale painting since the Empire. The emphasis on battle painting and the effort to address the entire sweep of French national history echoed Louis-Philippe’s program for the new museum in Versailles. Nonetheless, notes for his proposal suggest he embraced national conquest and the civilizing mission.6 Whatever Delacroix’s motivations, a great distance separates this initial idea from those in his eventual contribution to the palace.

Delacroix proposed to paint the spaces under the arches of a second great room, the Hall of Conferences, with examples of patriotism and devotion to the law from ancient history:

1.Lycurgus facing down the furious sedition of the people of Lacedaemonia.

2.The envoys of the Senate bringing the emblems of dictatorship to Cincinnatus.

4.The senators of Rome, immobile in their ivory seats, at the moment the Gauls sack Rome.

These paintings were to be surrounded by allegorical figures in grisaille representing the ideals embodied in each subject, which Delacroix specified as “Law, Courage, Eloquence, etc.”7 This cycle relied on a more traditional, classical language to speak generally of the ideals that should guide the legislators who used the palace. Two exempla virtuti from Plutarch and two from Livy—this was history painting at the service of good government in the great tradition of civic humanism. The story of Lycurgus facing down the rebellion of the Spartans was a lesson in courage from one of the original lawgivers. Precipitated by the austerity of Lycurgus’s reforms, the rebellion petered out when Lycurgus showed his bloodied face to the crowd. The funeral of Phocion was the subject of one of Poussin’s most famous pictures. The Athenian politician embodied the virtues of honesty, principled defiance, selflessness, and frugality and was perhaps a pointed choice for the July Monarchy’s notoriously venal deputies. Cincinnatus was a common enough subject, but the emphasis here on the moment when the Roman Senate called him to be dictator has shades of Bonapartism about it and seems to point up the weaknesses of legislative assemblies. The Roman senators in their mansions, unflinchingly awaiting the attack of the Gauls, had few, if any, precedents in painting. It placed peculiar emphasis on the triumph of the barbarians, a theme that would become very important in the library murals. Overall, the program promised edifying lessons but was curiously idiosyncratic and potentially critical of legislators.

Finally, there was the Deputies’ Library, by far the most complicated space, with its two hemicycles and five cupolas. Delacroix proposed that each cupola “would be devoted to some branch of human knowledge, and the [four pendentives in each] would represent the most famous men in each specialty.” The hemicycles would depict historical episodes honoring letters or philosophy. The specific subjects for the hemicycles were to be:

1.The Senate and the Roman people, having transported Petrarch to the capitol, bestow a triumph upon him and crown him with a laurel wreath.

2.The Phaedo. Socrates, in the middle of a banquet and surrounded by Plato and other philosophers following his lessons, discourses on the immortality of the soul.

The complex program for the cupolas was as follows:

1.Theology, represented by the fathers of the church and the doctors of the Christian faith: Saint Jean Chrysostom, Saint Jerome, Saint Basil, and Saint Augustine. They were to be surrounded by various attributes and allegorical figures representing divine love, faith, penitence, and meditation.

2.History and philosophy, represented by Pythagoras, Descartes, Tacitus, and Thucydides, surrounded by allegorical figures referring to the history of philosophy.

3.The sciences, represented by Galileo, Aristotle, Archimedes, and Newton. Here Delacroix was more specific about how he would depict each:

a.Galileo, in chains, determines the various orbits of the planets.

b.Aristotle describes the different kingdoms of nature.

c.Newton, plunged deep in meditation, holds the apple that first gave him the idea of gravity.

d.Archimedes, preoccupied with the solution to a problem, does not see the barbarian [sic] about to kill him.

4.The arts, represented by Raphael, Michelangelo, Rubens, and Poussin. Delacroix elaborated on the exact way in which he would depict “these four artists, considered as the most famous representatives of art in the modern period”:

a.Raphael, holding his pencils, leans upon a divine figure representing grace.

b.Michelangelo, holding the model for the dome of St. Peter’s, surrounded by four small genii representing painting, sculpture, architecture, and poetry.

c.Rubens, holding his luminous palette, carried by a winged lion.

d.Poussin, near an antique torso and his painting of Eudamidas.

5.Poetry, represented by Homer, Virgil, Dante, and Ariosto. Again Delacroix specified the subjects more precisely:

a.Blind Homer holding his staff and lyre, with an eagle clutching a laurel branch gliding over his head.

b.Virgil seated, holding his tablet. At his feet is the wolf nursing Romulus and Remus, indicating the cradle of Rome, and near him is Rome herself, in all her power, surrounded by the spoils of the entire world.

c.Dante lifted up by the emblematic figure of Beatrice and yearning for the eternal spheres, whose brilliance dazzles his mortal eyes.

d.Ariosto, surrounded by trophies of chivalry, seizing his lute and preparing to sing.8

The focus in all the proposed murals was squarely on great men of the arts, letters, and sciences, as was customary for imagery in libraries. As Hannoosh notes, “The status of the library as the repository of civilization had motivated most library decoration since antiquity, particularly in the form of statues, busts, and medallions of civilization’s most illustrious representatives; decorating served frequently as a means of cataloguing, identifying the author or subject of the books in the vicinity.”9 The setting apparently moved Delacroix away from the patriotic and politically exemplary modes of the other rooms: only two Frenchmen were included, and few of the subjects offered lessons related to political virtue. The theme of civilization was necessarily present, in the sense of the great individual cultural achievements of the West from antiquity to the modern world, but it was not particularly explored as a social development, and barbarism was emphasized in only one subject (Archimedes), though a number of others at least implicitly thematized it.

In September of 1838 the government decided to commission only the ceiling of the library from Delacroix and to assign the other rooms to Horace Vernet, François-Joseph Heim, and Alexandre-Denis Abel de Pujol. Delacroix almost immediately had doubts about his original proposal. He wrote to a friend, “The subjects I had thought of have problems, and if I find a better idea, which I think is very possible, I will take it. . . . It would have to be a fertile idea, with not too much reality, and not too much allegory; in short, something for all tastes.”10

Over the course of the next few years Delacroix considered hundreds of possible subjects for the individual paintings in the ceiling, and numerous alternatives for organizing the ceiling as a whole. Many of his ideas attempt to organize the ceiling using Jacques-Charles Brunet’s system for cataloguing library collections—the very system used in the Deputies’ Library—but he found it difficult to make the divisions in the ceiling correspond to Brunet’s classifications.11 Anita Hopmans has established that when Delacroix received a new commission in September of 1840 to paint the dome and hemicycle of the Library of the Chamber of Peers in the Luxembourg Palace, he used some of the ideas originally conceived for the Bourbon Palace.12 When he finally began to paint the pendentives for the Deputies’ Library, in October of 1841, he started with the cupola devoted to the sciences, now separated from the arts in contradistinction to Brunet’s system. The four pendentives would illustrate subjects that had emerged over the entire course of his planning to date. Next, in 1843, he completed the cupola devoted to history and philosophy, combining two categories that Brunet had kept separate. He was still experimenting with new ideas for the remaining cupolas, but without much adherence at all to Brunet’s scheme. The various plans reveal that he moved subjects from cupola to cupola. Hopmans convincingly asserts that some of the oddities in the program, such as the presence of The Education of Achilles among subjects about poetry, or The Chaldean Shepherds among subjects about history and philosophy, are the result of his extemporaneous, unsystematic approach to the ceiling: he had become attached to certain subjects and fit them in where he could in the final scheme. In several instances, a subject initially conceived for one cupola ended up in another.13

The crucial idea of juxtaposing Orpheus and Attila in the hemicycles and thereby framing the murals with the idea of civilization and barbarism came relatively late in the gestation of the project. The artist had considered Orpheus as a subject in a number of earlier drawings and plans, some of which make it clear that he saw Orpheus as a way of making explicit the theme of civilization, but he considered using him in standard allegories of war, peace, agriculture, and industry.14 The idea of using Attila came later. In the lower left of a drawing from 1843, he quotes from a newspaper article describing James Barry’s murals for the building of the Royal Society of the Arts (which also depict Orpheus) and notes that the first two paintings in Barry’s cycle show man passing from “a state of nature” to “a state of society.”15 In the bottom right of the same drawing, Delacroix quotes from another article in which a journalist describes his first thoughts upon seeing Moscow: “these old walls had trembled at [Napoleon’s] approach, and the inhabitants of this town had fled before him as once the fields of Italy had been deserted by their inhabitants before Attila’s horse.”16 Delacroix adds, “Attila tramples Italy and the arts.”17

On 27 February 1843 Delacroix wrote to his assistant Louis de Planet to say that he had almost finished the sketches for the hemicycles.18 Between 1843 and 1846 the pendentives were glued into place and finished. The pendentives for at least two of the cupolas—those devoted to science and to history and philosophy—appear to have been largely completed before Delacroix arrived at the idea for the hemicycles; the testimony of his assistants makes clear that many of the remaining pendentives were completed afterward.19 Further evidence that Delacroix experimented with the overall program well after completing some of the first paintings is found in a preparatory drawing for the Orpheus hemicycle, which dates to 1843 at the earliest.20 Delacroix was still listing and crossing out possible subjects for the pendentives. Because of cracking in the vaults, the hemicycles were not completed until late December of 1847.21

The final arrangement of the paintings is summarized in figure 8. Only two of the twenty pendentives illustrate subjects related to the original plan, and the hemicycles are completely different. For my purposes, several points should be emphasized. Because Delacroix did not receive the commission for the entrance hall, his original idea to celebrate French civilization through foreign conquest in his mural program necessarily disappeared. Yet even in the library murals he moved away from modern and French subjects: they now all come from ancient history—Greek, Roman, or biblical—and they lack clear chronological order.22 As opposed to the initial emphasis on great men, the final ceiling has at least two scenes that lack a singular hero (The Chaldean Shepherds and the Babylonian Captivity), some that emphasize the demise of a hero (Pliny, Archimedes, and Ovid), others that revel in the barbarous death of a hero (Seneca, John the Baptist), and at least one that focuses on a barbarian (Attila). Most of his protagonists, no longer conceived as part of the minimally narrative scenes that primarily commemorated their cultural contributions, are now embedded in complex narratives that reflect in various ways upon the rise and fall of civilization, much like the subjects originally proposed for the Hall of Conferences. All these changes bring the murals closer to the understanding of civilization that emerges in Delacroix’s journal after 1847: skeptical about the possibility of progress and inclined to see both civilization and barbarism as constitutive features of mankind.

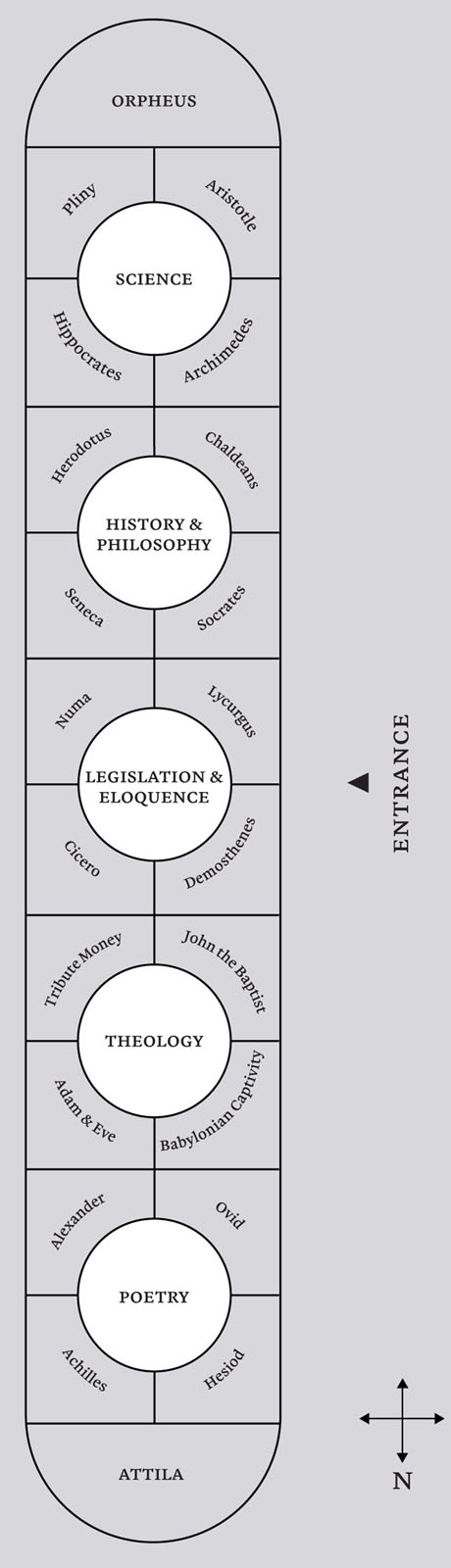

FIG. 8 Plan of Delacroix’s ceiling in the Library of the Palais Bourbon, Paris. Drawing by YooJin Hong.

The theme of each dome (Science, History and Philosophy, Legislation and Eloquence, Theology, Poetry) is indicated in the circles. The subject of each pendentive is indicated in the surrounding triangular areas. The subjects of the hemicycles are in the half circles at either end. The diagram is not to scale.

The program confused critics from the start. Louis de Ronchaud complained, “I have not been able to see very clearly the mysterious correlation that must exist between the diverse subjects.”23 He hoped that the unveiling of the hemicycles (which were still unfinished) would make the overall message more apparent. Louis Clément de Ris, who saw the murals just after the hemicycles were unveiled, drew the logical conclusion that the pendentives must depict events between the rise (Orpheus) and fall (Attila) of ancient civilization, but then noted that the pendentives did not establish a clear chronological narrative moving between these two points. Furthermore, some pendentives, such The Education of Achilles and The Expulsion of Adam and Eve, did not obviously treat the theme of civilization and barbarism.24 These critics were responding to real difficulties in the murals. The significance of the individual paintings and the ways in which they added up to a larger program was anything but self-evident.

In answer to early complaints about the indecipherability of the ceiling, Delacroix offered a “categorical explanation of [his] intentions” to the critic Théophile Thoré and asked him to print it in Le constitutionnel. His “explanation” is primarily a list of the individual subjects and says curiously little about the ceiling’s larger significance. He notes that the paintings “are related to philosophy, history and natural history, law, eloquence, literature, poetry, and even theology. They recall the divisions adopted in all libraries, without, however, following their precise classification.” In fact, these categories do not describe very well the subjects or the organization of the murals. For example, Delacroix does not mention science (only natural history), and the subjects he drew from the Bible have ambiguous theological significance. He does not explain the placement of The Education of Achilles among poetic subjects, or the presence of The Chaldean Shepherds, the inventors of astronomy, among historians and philosophers. The themes now conventionally associated with each cupola—(1) Science, (2) History and Philosophy, (3) Legislation and Eloquence, (4) Theology, and (5) Poetry—attempt to provide coherence, but they do not resolve these difficulties. Delacroix is somewhat clearer in regard to the hemicycles. In one, “Orpheus brings the Greeks, dispersed and given over to the savage life, the benefits of the arts and civilization.” In the other, “Attila, followed by his barbarian hordes, tramples under the feet of his horse Italy, fallen on ruin.” In short, Delacroix points to the obvious contrast between the birth of civilization and its eventual destruction by barbarism but offered no real overarching explanation of the program.25

Art historians have struggled to tease out of the cycle a clear meaning. Robert Hersey proposed in 1968 that the murals pictured the course of civilization according to the theories put forth in Giambattista Vico’s Scienza nuova seconda (1725).26 Hersey sought a literary source and discursive lesson behind the decorations, very much in the iconological mode of interpretation formulated by Erwin Panofsky, Edgar Wind, and others around Italian Renaissance mural painting, but his account has not held up under scrutiny. Hopmans’s subsequent demonstration that Delacroix developed the program through a gradual improvisatory process over the course of many years suggests its program does not have a single predetermined source.27 More recently scholars have sought to locate political meanings in the ceiling, particularly in light of the library’s intended purpose, to serve the Chamber of Deputies. Jonathan Ribner has pointed out that Delacroix placed the cupola devoted to legislation and oratory over the main entrance to the library. The pendentives in the cupola—devoted to Lycurgus, Numa, Demosthenes, and Cicero—extol qualities of central importance to legislators: inspiration, meditation, preparation, eloquence, and probity. Other paintings also speak directly to the business of the Chamber. The pendentive devoted to the Tribute Money, which seems anomalous in regard to civilization, makes more sense as a comparison of earthly law and divine law, and it addresses taxation, a fraught issue under the July Monarchy. One hemicycle features Orpheus, commonly identified as the first lawgiver, and the other prominently includes the allegorical figure Eloquence, a key attribute of the legislator, as one of Attila’s principal victims.28

Daniel Guernsey has gone further, arguing that the ceiling’s meditation on “the birth, rise and decline of ancient civilization functioned principally as an internal critique of the July Monarchy.” Guernsey places Delacroix’s murals in a long tradition of politically engaged humanist discourse that sought to find guidance in ancient and modern texts. He relates them to meditations by Cicero, Seneca, Plutarch, Tacitus, Montaigne, Rousseau, and others addressing issues such as good governance, the dangers of luxury, and the rise and decline of societies. For Guernsey, the ceiling served as a moral exhortation to the ruling elite of the July Monarchy, offering examples of political virtue and vice. He concludes “that when Delacroix linked legislation, civic patriotism and eloquence as a meaningful ensemble denoting civilized values he located his murals, even if unintentionally, in a discursive tradition that has been neglected in the scholarship on the Palais Bourbon Library murals, a tradition that deepens our understanding of the program’s content: civic humanism or civic republicanism.”29

There are difficulties with Ribner’s and Guernsey’s interpretations, but they raise the necessary question of Delacroix’s political or moral intentions.30 Guernsey’s account is especially worthy of attention because he develops a learned, speculative reading derived from the classics, and it is my guess that Delacroix would have delighted in its humanism, creativity, and daring. Moreover, many of the figures pictured in the ceiling—Lycurgus, Numa, Demosthenes, Cicero, Hippocrates, and Seneca—were primarily discussed in both ancient and modern texts as models of patriotism and political virtue, and this is surely how Delacroix understood them, at least in part. Even if the political significance of the ceiling as a whole is not as coherent or pointed as Guernsey would have it, some of the pendentives are unambiguously political. The condemnation of venality and corruption in the Cicero and the Hippocrates addressed real problems in the legislature of the July Monarchy, the Demosthenes spoke to the dedication and talent demanded of legislators, and the Lycurgus and the Numa proclaimed the importance of laws. In short, there clearly was political bite in some of Delacroix’s subjects.

And yet Delacroix’s political disillusionment had been growing over the course of the July Monarchy, making it unlikely that he primarily intended a political allegory. In January of 1847, after a dinner at the home of Adolphe Thiers (who was then making his bid to become the leader of the opposition in the Chamber of Deputies), he complained, “From time to time, someone speaks to me about painting, noticing that these conversations about politicians, the Chamber, etc., bore me profoundly” (334). The following month he wrote, “Moralists, philosophers, I mean the real ones like Marcus Aurelius and Christ . . . never spoke about politics. The equality of rights and twenty other chimeras never preoccupied them.” According to Delacroix, they recommended resignation to destiny. He continued, “Sickness, death, poverty, the troubles of the soul, are eternal and will torment humanity under all regimes; the form, democratic or monarchical, makes no difference” (350). These are obviously not the words of a man deeply engaged in the work of the legislature. If indeed he had intended the ceiling of the Bourbon Library as a commentary on the Chamber of Deputies under the July Monarchy in some limited way, as it seems he did, his interest in its political functions was waning. When a revolution swept away the July Monarchy just months after he completed the ceiling, he must have fully recognized the peril of joining his painting to the contingency of modern politics. In any event, his mural paintings for subsequent governments have less of the political specificity and moralizing content, such as it was, of the ceiling in the Deputies’ Library.

The interpretation I offer here draws primarily on that of Michèle Hannoosh, who has suggested that, rather than offer a linear narrative of civilization, or even a didactic cycle illustrating the accepted understandings of civilization, Delacroix interrogated the concept. In her view, the murals “explore the nature of civilization itself: its fragility, certainly—an idea appropriate to the place housing its few remains—but also its contingency, weakness, and even potential for perversion. Such was the value of the image among so many words: to convey the complexity of this essentially human phenomenon, its nuances and contradictions.”31 Rather than define civilization or chart its progress, Delacroix entered into the conundrums and contradictions that would preoccupy him especially in his journal in subsequent years. If the hemicycles promise a narrative about the rise and fall of civilization, the pendentives systematically undermine any sense of continual progress from barbarism to civilization. The theme of barbarism erupts unexpectedly and repeatedly, upsetting the notion that civilization is a stable, cumulative, or permanent achievement. It was precisely this aspect of the ceiling that confused critics.

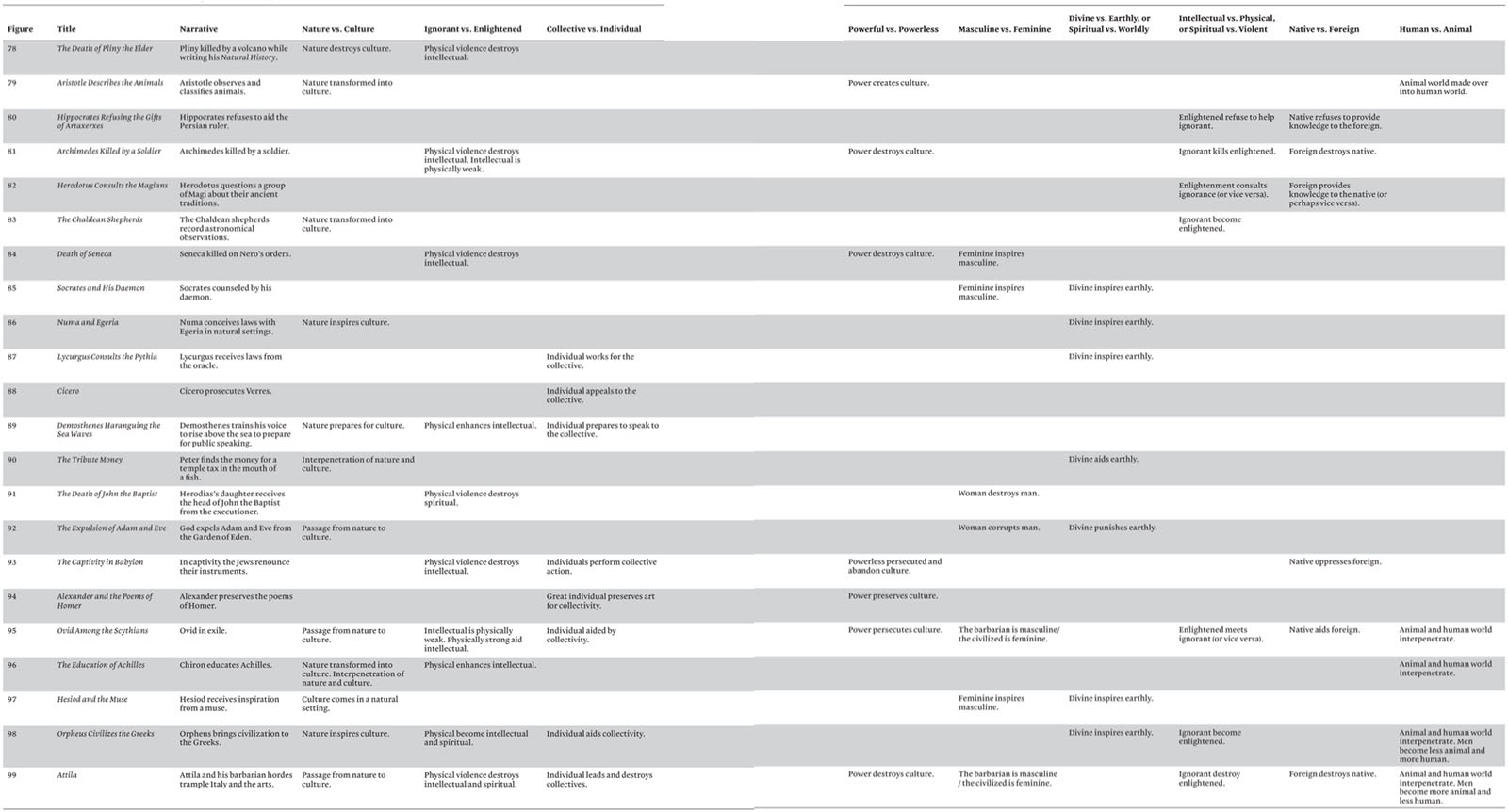

It is striking that the individual pendentives of the ceiling divide the basic antithesis of civilization and barbarism into many other binary oppositions. Figure 9 offers in schematic form some of the antitheses that run through the ceiling. Those listed along the top right of the chart could be extended, and readers may consult the appendix to see particular themes in individual paintings developed in a more nuanced manner. Taken together, they suggest the persistent use of antithesis in the ceiling and point to a logic underlying the program. Delacroix selected narratives that focused on moments when opposites meet—when, for example, the refined encounters the savage, or the animal is found in the human, or the divine touches the earthly—and these moments produce either civilization or barbarism. In this sense civilization and barbarism assert themselves as the master terms in the fundamental antithesis to which all others relate.

FIG. 9 Chart of Antitheses in the Ceiling of the Library of the Palais Bourbon, Paris

At the same time, the meeting of any particular pair of opposites will yield varied and unpredictable outcomes: the joining of nature and culture, or of the refined and the uncouth, or any other mediation between opposites, can produce either civilization or barbarism. For example, nature might inspire culture (Aristotle, Pliny, Chaldean Shepherds, Demosthenes), but can destroy it as well (Pliny). The divine both fosters human knowledge (Socrates, Numa, Lycurgus, Hesiod) and condemns it (Adam and Eve). Inspiration often comes to man through divine intervention (Socrates, Numa, Lycurgus, Hesiod), but it may come directly from nature (Aristotle, Chaldean Shepherds, Demosthenes). Political power can nurture the individual accomplishments that create civilization (Alexander, Cicero), but frequently it destroys or hinders them (Archimedes, Seneca, John the Baptist, the Babylonian Captivity, Ovid), and personal development occurs both within (Cicero) and outside (Demosthenes, Achilles) society. The human is both distinct from the animal (Aristotle) and animal-like (Achilles, Chiron, Orpheus, Attila). Interactions with the foreign have uncertain outcomes, sometimes producing new cultural achievements (Herodotus), sometimes extinguishing or stifling them (Archimedes, the Babylonian Captivity), and sometimes producing complex results (Hippocrates, Ovid). Civilization may be the result of feminine influence (Socrates, Numa, Hesiod), but it may feminize men (Ovid) or diminish their virility (Archimedes) in ways that threaten its survival. The ceiling is a record of Delacroix’s open-ended and conflicted meditations on civilization.

Delacroix employed a number of devices that encouraged the viewer to work through and compare these antitheses. This is accomplished most obviously by the repetition of motifs—spears, swords, animal hides, lyres, and especially scrolls—to link separate paintings and make apparent their points of intersection. Fundamental themes such as exile, patriotism, inspiration, and cross-cultural exchange also repeat across the ceiling. Patterns emerge in the organization of the pendentives. For example, the cupola devoted to legislation and oratory contains two divinely inspired lawgivers who were compared by Plutarch and juxtaposes them with two worldly orators who were also compared by Plutarch. The cupola devoted to religion divides neatly into two subjects from the Old Testament and two from the New Testament. Such repetitions and patterns promise an underlying order, but that promise is not kept. The viewer is encouraged to compare themes, but the results of that exploration are inconclusive. Again, no comprehensive or consistent resolution of the various antitheses emerges.

For all of its open-endedness, the ceiling is inevitably marked by some striking emphases and limitations. Civilization is not understood as the result of larger social and natural forces such as climate, geography, religion, and race—the factors that many eighteenth- and nineteenth-century theorists were fond of citing. These factors figure into individual narratives, but civilization is primarily the work of creative individuals, especially those in the arts and sciences, as in Guizot’s second definition of civilization. The ceiling emphasizes inspiration, genius, and the creator’s relationship to power, and a surprising number of paintings depict creativity as the product of a spiritual communion with a deity. Women appear in limited roles: as inspirations to the male creators of civilization and victims of male barbarians, but not as agents carrying out civilization’s work. There is perhaps a preponderance of Stoic subjects in which the hero’s achievement is marked by self-abnegation, devotion to principle, and discipline, and where luxury or women tempt, corrupt, and weaken. Perhaps, too, there is some overall sense of a general rise of civilization among Greek subjects, and a greater emphasis on decline in Roman subjects, where themes of violence, corruption, injustice, luxury, exile, and the like are more prevalent.32

What marks the ceiling most, however, is its refusal to characterize the civilizing process as one of more or less ineluctable progress leading to the present. In mid-nineteenth-century France, with its enormous and growing faith in progress, the barbarism/civilization opposition was normally mapped onto the binary pair past/future. Delacroix’s ceiling, in contrast, says very little about the chronology of civilization. His aim was neither to chart a trajectory of civilization nor to privilege the present. Civilization is not a stable achievement. On the contrary, it must be achieved again and again. At any given moment civilization might blossom or wither away. The course of history remains occult.

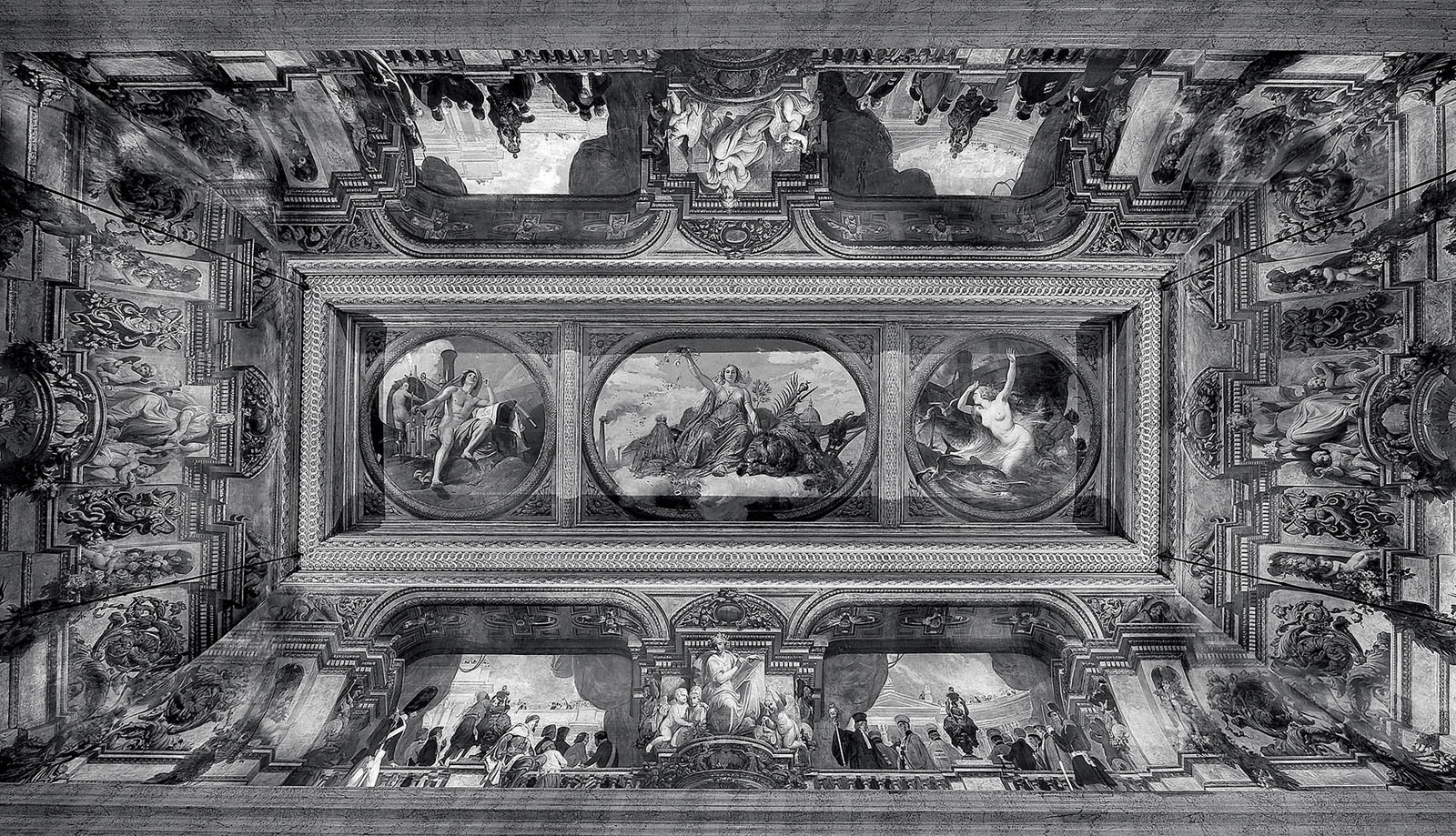

Most other contemporary mural projects devoted to civilization, of which there were many, offered reassuring narratives of progress. Delacroix’s ceiling stands in absolute contrast to Horace Vernet’s contribution to the Bourbon Palace, in the Hall of Peace (fig. 10), where he covered the center of the gigantic ceiling (eleven by twenty meters) with three paintings (fig. 11): The Genius of Steam on Earth, Peace Enthroned Before Paris, and Steam Putting to Flight the Sea Gods. The first painting shows an Apollo-like personification of “the Genius of Steam,” or “Science,” with an air pump, a telescope, an anvil, engineering plans, and a locomotive guided by a putto. In the center painting, Peace, strewing flowers, sits amid Parisian monuments, smokestacks, a beehive, a cannon, war trophies, sheaves of wheat, a sleeping lion, a plow, and grapevines. The final painting is the oddest of the three because in it industrial technology, embodied in a huge black steamship, literally puts classical deities and animals to flight: the modern almost violently displaces the traditional and the natural. Around the edges of the ceiling, on the coving, Vernet has depicted various contemporary figures—soldiers, foreign dignitaries, and public officials—behind balustrades, as well as architectural and sculptural ornaments. His murals blithely combine classical allegorical figures with a hodgepodge of new and old emblematic signs representing technology, industry, military might, peace, and agriculture.33 They are a celebration of the recent course of history under the July Monarchy, but their bizarre iconography lacks nuance and runs roughshod over rules of decorum. It is easy to appreciate Delacroix’s disgust when he saw them: “There is a volume to write about the horrible decadence of nineteenth-century art that this work reveals.”34 For Delacroix—and it is hard not to sympathize with him—Vernet’s tribute to modern civilization unwittingly shared the puerility and self-congratulatory optimism of much contemporary culture.

FIG. 10 Horace Vernet, ceiling of the Hall of Peace, 1838–47. Oil on canvas. Palais Bourbon, Paris. Courtesy of the Assemblée nationale.

FIG. 11 Horace Vernet, ceiling of the Hall of Peace (fig. 10), 1838–47, detail of the central portion, with The Genius of Steam on Earth, Peace Enthroned Before Paris, and Steam Putting to Flight the Sea Gods. Paris, Palais Bourbon. Courtesy of the Assemblée nationale.

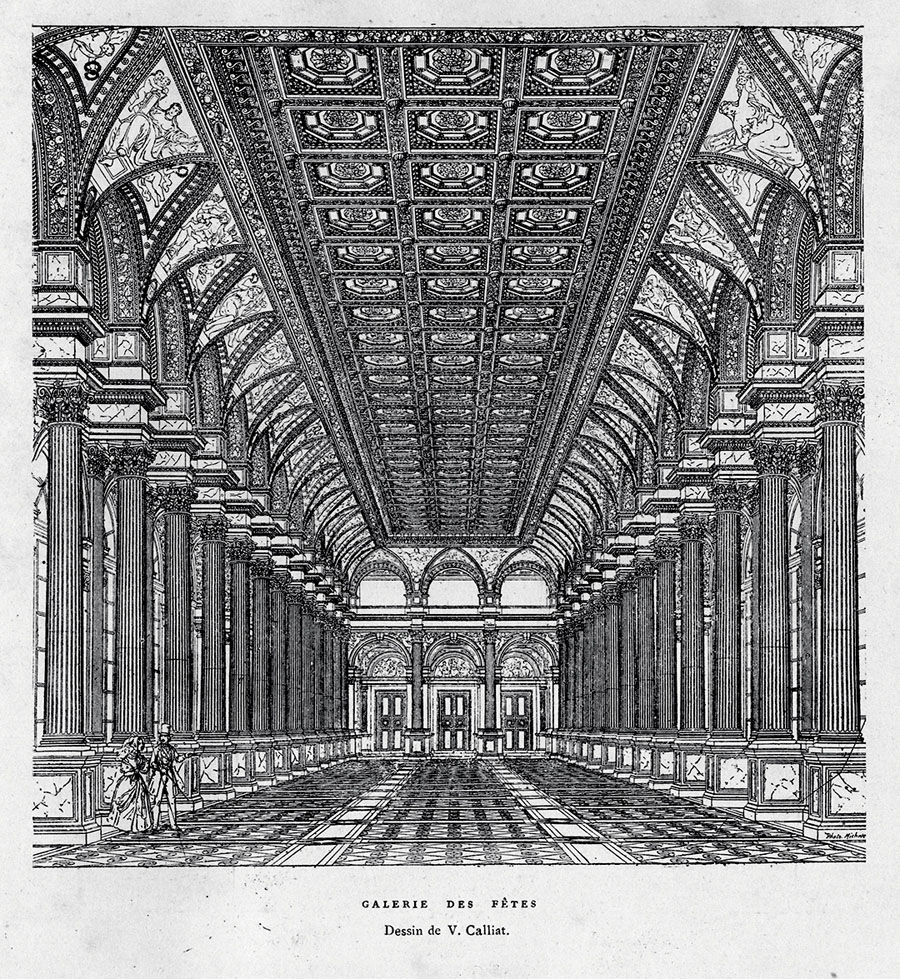

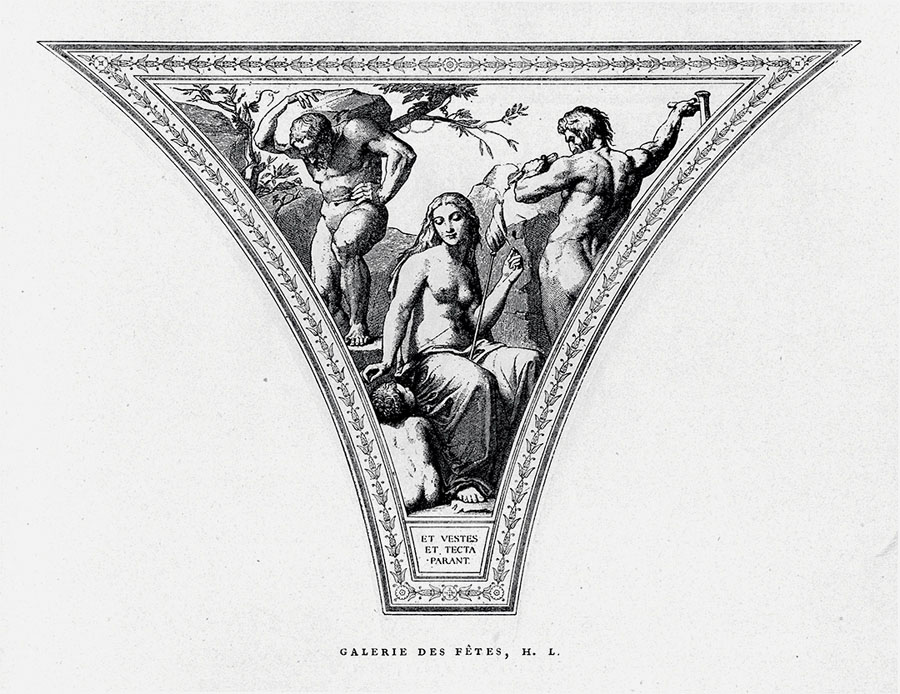

More academically conventional mural paintings devoted to civilization shared Vernet’s unshakable faith in progress. Henri Lehmann’s now-destroyed murals on the pendentives of the Galerie des Fêtes in the Hôtel de Ville (completed 1853, fig. 12) recounted, as one contemporary critic described it,

FIG. 12 Victor Calliat, The Galerie des Fêtes, from Marius Vachon, L’ancien Hôtel de Ville de Paris, 1533–1871 (Paris: A. Quantin, 1882), 69.

________

nothing less than an encyclopedic history of the world, from Adam and Eve (“humanum oritur genus”) to the most refined civilization, as it would appear, for example, to the stunned gaze of a savage brought from the center of the new Americas watching a performance of the opera. Thus, with multiple, successive allegories, we see man march in all his struggles, his efforts and his conquests, through religions, war, sciences, and arts. It is all of humanity illustrated and progressing from brutal action to fecund meditation. . . . It is a comprehensive journey through humanity, having two stages: barbarism—civilization.35

________

The reference to the dazed savage reveals just how self-confident this writer felt in front of Lehman’s version of civilization, and other commentators offered similar responses.36 Surviving reproductions of the fifty-six separate paintings—for example, one of humans procuring materials for clothing and shelter (fig. 13)—reveal that the ceiling used anodyne narratives and allegories and an academically unimpeachable style to embody various achievements on the path to modern civilization. The cycle offered a triumphant version of history characterized by gradual but continual progress, culminating in the present.37

FIG. 13 Danguin after Henri Lehmann, Et Vestus et Tecta Parant, from Marius Vachon, L’ancien Hôtel de Ville de Paris, 1533–1871 (Paris: A. Quantin, 1882), 77.

Even Delacroix’s friend Chenavard, who similarly dismissed the notion that modernity represented a pinnacle in the history of mankind, could not resist the idea of a clear pattern in history. During the Second Republic he secured the commission to decorate the interior walls and floor of the Pantheon. He proposed sixty-three enormous murals, a portrait frieze, and four decorated piers all depicting the history of civilization from Adam and Eve to Napoleon Bonaparte, and an enormous floor mosaic depicting what he termed “social palingenesis,” or the past, present, and future of mankind (fig. 14). Chenavard called his decorations “a sort of historical gallery, offering in a series of pictures placed in chronological order, the great religious, political and civil events which have marked the procession of humanity through the ages.”38 He lost the commission before completing his plans, but his surviving sketches give a clear picture of his intentions. His cycle focused on the achievements of great men of history, as was common, but it sought to include both the East and the West in order to offer a more inclusive, universal history, as opposed to a particular sectarian view. In his elaborate theory, too complex to allow for a full discussion here, and according to his own estimates, civilization began with Adam and Eve, reached a pinnacle with the appearance of Jesus Christ 4,200 years later, would be in full decline when American modernity dominated the world in circa 2100, and would end in total destruction 2,100 years after that. Though he shared Delacroix’s grim view of modernity, he still emphasized predictable periods of progress and decline.39 Delacroix’s murals undercut such certainties and saw the future as fundamentally unpredictable.40

FIG. 14 Paul Chenavard, Social Palingenesis, or The Philosophy of History, 1848–51. Oil on canvas, 303 × 380 cm. Musée des beaux-arts de Lyon.

Chenavard’s mosaic proposed that great geniuses were entirely a product of the historical moment, consistent with his belief, discussed in the previous chapter, that present-day artists had no possibility of rivaling the great art of the past. This points to a final difference between Delacroix and many of his contemporaries, one that illuminates not only his unique conception of civilization but also his success with mural painting, a format in which many of his colleagues failed spectacularly. Marc Gotlieb has examined the feelings of belatedness and inadequacy that many French painters in the middle of the nineteenth century experienced in relation to the past.41 Their sense of inferiority was felt most acutely in relation to mural painting, which was widely perceived to be the highest form of painting and the site of the greatest artistic achievements of the past. Many major nineteenth-century mural projects ended in abject failure (those of Ernest Meissonnier and Chenavard at the Pantheon) or dubious results (those of Antoine-Jean Gros at the Pantheon and Paul Baudry at the Opera), in no small part because painters felt unequal to the task of emulating the great examples of the past.

Delacroix is the greatest exception to Gotlieb’s argument. Given his reverent attitude toward the Old Masters and his belief that the art of his own day was in full decline, he might predictably have suffered especially from a feeling of inadequacy in relation to past mural painters. But, on the contrary, he was the most prolific and successful mural painter in mid-nineteenth-century France. Delacroix’s ability to surmount the burden of the past was perhaps attributable to what Harold Bloom would call his “strength” as an artist: simply put, he was capable of drawing inspiration from the Old Masters without succumbing to derivativeness or despair at coming after so much had already been accomplished.42 As noted in chapter 1, he considered himself the equal of the great painters of the Renaissance and the Baroque, and posterity has largely confirmed his own opinion of himself.

The difference between Chenavard’s and Delacroix’s understanding of civilization suggests a more specific explanation. In contrast to Chenavard’s view that individual achievements are wholly characteristic of their historical moment, Delacroix believed that they were not tightly determined by their historical context. It is not surprising, then, that in his ceiling many individuals achieve greatness sometimes with the aid of civilization but more often in its absence or in the face of barbarism. He was drawn to the primal, untamed world outside of civilization: the sublime violence of Attila and his horde; the crouching, animalistic tribe that greets Orpheus; the powerful, rustic Scythians aiding Ovid; the exotic appearance of the Persians; the Roman Empire’s decadence and corruption. At least nine of the twenty-two murals in the Deputies’ Library depict barbarians or acts of barbarism. Fifteen are set in nature. Eight feature animals or beasts prominently. The ceiling is as much about civilization’s others—the natural, the barbaric, the bestial, the ignorant, the savage, the violent—as about civilization. Delacroix envisioned the artist or intellectual in relation to the uncivilized—it was the ground against which he defined himself. Many paintings focus on the source of inspiration, repeatedly personified by a female deity but often located in nature itself. Perhaps the most common antithesis in the murals is that between nature and culture, depicted in passages from nature to culture or vice versa. Here emerges the special appeal of nature and barbarism to Delacroix: it was the untamed, precivilized raw material upon which the artist exercised his work.

Delacroix’s efforts with the ceiling bore comparison to those of his antique heroes. His conversations with Chenavard reveal that he saw himself, like the figures in his murals, as a man of talent working in an unpredictable and often barbaric world. While he shared Chenavard’s scorn for modernity and belief that contemporary art had fallen into an inferior state, this only made his own struggle as an artist more like the struggles of the heroes in his ceiling. In his essay “Des variations du beau” he asserts that great artists like Raphael, Titian, Rubens, Dante, and Shakespeare owed nothing to the past or the present:

________

Each of these men appeared all of a sudden and owed nothing to that which preceded him, or to that which surrounded him: he is like this Indian god who created himself, who is at once his own ancestor and last descendant. Dante and Shakespeare are two Homers, appearing with a whole world that is theirs, in which they move freely and without precedents.

Who can regret that, instead of imitating, they invented? That they were themselves, instead of taking up Homer and Aeschylus again? . . . The true primitives are those with original talents.43

________

The most original artists always create their work out of whole cloth, as if they worked without precedents, surrounded only by barbarism and nature. Thus Delacroix emphasized primordial moments of creation and destruction in the face of nature and barbarism. Rather than see civilization as an accumulated weight and a set of past achievements, he saw it reborn in every creative act.44

In this regard Delacroix’s approach to civilization in the Bourbon Library bears comparison with Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s Apotheosis of Homer (fig. 15). Ingres placed Homer, with personifications of the Iliad and the Odyssey at his feet, at the center of a group of the greatest representatives of the arts from classical antiquity down to the eighteenth century. The more ancient figures stand closer to Homer, while the more modern figures, depicted in more vivid detail and darker tones, stand in the corners, closer to the viewer. The painting suggests that the most exalted forms of artistic achievement exist in the distant past and that subsequent artistic achievements descend directly from them. The picture’s hierarchical rhetoric transforms tradition into a weighty, intimidating presence by suggesting that greatness is achieved by following the example of the past. Modern figures find inclusion in the picture only to the extent that their own work approaches that of their illustrious forebears. The critic Etienne Delécluze summed up this attitude when, after reviewing the great artists included in the painting, he concluded, “all that can be done now is to modify these archetypes indefinitely.”45 Ingres’s quotations and manipulations of classical sources reinforce the idea that artistic greatness can only be achieved by emulating the past. We might question how stultifying tradition actually was for Ingres and indeed the extent to which he is adequately characterized as a classicist, as he willfully distorted his sources in picture after picture and was every bit as formally innovative as Delacroix, but he nonetheless came to embody respect for tradition after midcentury.

FIG. 15 Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, The Apotheosis of Homer, 1827. Oil on canvas, 386 × 515 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris. Inv. 5417.

In a few important respects Delacroix’s work in the Deputies’ Library resembles Ingres’s Apotheosis of Homer, perhaps surprisingly so given the contrast normally drawn between them. Like The Apotheosis of Homer, the Deputies’ Library murals do not suggest a history of civilization based on progress and continual improvement. And like Ingres, Delacroix used the ceiling as an opportunity to emulate the styles of the Old Masters, including the work of Ingres’s idol Raphael. Ingres may have been more exclusive and orthodox in his choice of artistic models, whereas Delacroix showed allegiance to artists such as Rubens, Veronese, and Titian. Moreover, Delacroix was not as inclined as Ingres to draw attention to his quotations, and he often modified them or combined them with very different models. For example, the Archimedes took its soldier from a print thought to be after Raphael, but it integrated this source into a larger image whose lighting follows Rembrandt and whose handling is Rubenesque.46 But these differences should not obscure their similar respect for great art of the past and their belief in its general superiority to the art of the present.

The crucial difference between Ingres and Delacroix was that Delacroix encouraged viewers to think critically on past examples of greatness, to weigh one example against another, to reflect on their contradictions, to draw their own conclusions. To repeat Hannoosh’s thesis, Delacroix defined civilization not as a canon of great men but instead, through its opposition to barbarism, as a set of conflicts that are seemingly always present in history, as much in need of definition in the present as in the past. The Deputies’ Library ceiling reveals the extent to which Delacroix viewed history as a creative enterprise that could serve as a means of understanding human experience.47 Epistemological questions about the objectivity or accuracy of the historical narratives in individual paintings are hardly relevant—the stories need only be plausible enough to provide a springboard to thought.48 Ancient history was not the dull, irrelevant, esoteric pursuit that it was fast becoming for many of his contemporaries. On the contrary, it provided a space of relative liberty for speculative thinking, free of the ideological imperatives that drove so much thinking about the present, an escape from and even an antidote to modernity, a form of resistance to the blind faith of many of his contemporaries in progress and the new.

Delacroix had traveled a remarkable distance from the unambiguous, triumphant, and nationalistic celebration of French civilization initially proposed for the entrance hall and the tribute to great artists and intellectuals of European history originally planned for the library. The murals became a critical meditation on civilization and barbarism as the project developed, one that upset any easy ideas of progress and tradition. They still contained a measure of allegorical content providing moral and political commentary on the present, but they courted ambiguity and open-endedness. Delacroix’s subsequent murals on the theme of civilization distanced themselves still further from overt didacticism, substituting instead an emphasis on the decorative possibilities of mural painting.

Delacroix’s next two major mural projects—in the Peers’ Library of the Luxembourg Palace and in the Apollo Gallery of the Louvre—are both about civilization as much as any other subject. He began the first in 1841 and finished it in 1846, working on it essentially contemporaneously with the Deputies’ Library, and executed the second just afterward, from 1849 to 1851. Both take up themes similar to those found in the Bourbon Palace, but they depart from the latter’s varied and extended speculations on the struggle between civilization and barbarism throughout ancient history. I argue here that they rely far more on the decorative effects of mural painting, in a sense substituting these for the richly discursive content of the Deputies’ Library. In the Apollo Gallery, in particular, Delacroix was engaged in an emulative competition with past masters of mural painting. The ceiling of the Deputies’ Library had turned away from the present in favor of an intensely intellectual exploration of the narrative content of its ancient historical and literary sources. It eschewed progressive and celebratory visions of history culminating in modernity, offering instead an open-ended contemplation of the past with no clear relation to the present. The ceiling for the Apollo Gallery was far more focused on its art-historical sources and offered the viewer an aesthetic release primarily through its painterly and figural aspects.

Like the Bourbon Palace, the Luxembourg Palace was a major government building—the seat of the Chamber of Peers—and it was undergoing substantial rebuilding during the July Monarchy. The decorations for the library were just as extensive as those for the Deputies’ Library, but large parts of them—five rectangular compartments on either side of the central dome—were assigned to Léon Riesener (Delacroix’s cousin) and the equally mediocre Camille Roqueplan. Their themes somewhat resembled those in the Deputies’ Library: Philosophy, Poetry, Eloquence, Gospel, Law, History, Industry, Military Genius, Politics, and Mathematics. Civilization was still very much at issue, but Riesener and Roqueplan embodied them in the usual bland allegories executed in an undistinguished manner.49 Delacroix received the commission for the central dome, its four surrounding pendentives, and an adjacent hemicycle. Given the limited space assigned to him and lack of control over the rest of the ceiling, perhaps Delacroix could not have pursued a program with the same complexly contradictory themes as at the Bourbon Palace. Whatever the reasons, his paintings in the Luxembourg Palace posited a more celebratory view of civilization, provided far less political commentary, and offered especially ingenious formal solutions, particularly in light of the architectural constraints of the site.

For the hemicycle, Delacroix repeated the subject of Alexander and the poems of Homer, to which he now gave more elaborate and exotic form (fig. 16). Thus the fragility of civilization, the fortuitous preservation of some of civilization’s greatest achievements, the role of libraries as repositories of civilization, and the violent competition between civilizations were all still themes.50 The pendentives beneath the dome have none of the narrative intricacy of those in the Deputies’ Library. Delacroix simply personified Eloquence, Poetry, Theology, and Philosophy. Painted to resemble bronze reliefs, their imagery and execution are not particularly remarkable.51

FIG. 16 Eugène Delacroix, Alexander Preserving the Poems of Homer, 1845. Oil and wax on primed surface, diameter 680 cm. Palais du Luxembourg, Paris.

Delacroix initially considered breaking the dome into compartments and pondered various mythological and literary themes. Eventually he settled on the idea of painting Virgil presenting Dante to Homer and other great figures from antiquity (fig. 17), drawing his inspiration very loosely from canto IV of the Inferno. This allowed him to represent many of the greatest antique poets, orators, warriors, statesmen, philosophers, and artists gathered in a timeless pastoral colloquium. The painting reveals once again Delacroix’s great familiarity with the classics: scholars have demonstrated that the figures’ selection and placement, as well as the surrounding iconography, provide a richly learned commentary on their various contributions to history and their relationships to one another.52 There is also again the fluid incorporation of past iconography: many of the figures derive from antique statuary, sometimes with great cleverness. For example, the figure of Demosthenes is based on an antique statue thought in the nineteenth century to represent the orator, and the image of Sappho comes from a third-century B.C. relief of the apotheosis of Homer. The many such quotations and allusions to antique, Renaissance, and Baroque models are all seamlessly incorporated into the final image, revealing once more Delacroix’s peculiar ease with tradition.53

FIG. 17 Eugène Delacroix, Dante and the Spirits of the Great, 1841–45. Oil and wax on primed surface, height 350 cm, diameter 680 cm. Palais du Luxembourg, Paris.

Yet the ceiling now presents civilization primarily as the sum of its greatest achievements, not civilization as a social process or as an impulse in constant struggle with barbarism.54 After choosing the subject, Delacroix noted that it “departs a bit from the banality of Apollo and the Muses, etc.,”55 but he had nonetheless moved back in the direction of Ingres’s Apotheosis of Homer insofar as he represented civilization primarily through its most illustrious past representatives and traced an intellectual lineage from Dante back to Homer. Indeed, one of the subjects he considered for the dome was an apotheosis of Homer.56 If the picture has none of the rigid hierarchical organization of Ingres, it nonetheless proposes as a setting for greatness a sanctuary or paradise—Delacroix called it a “sort of Elysium,” as opposed to Dante’s Limbo—that is just as removed from the here and now. For the general organization of the picture, Delacroix looked to none other than Ingres’s idol Raphael, and more specifically to Raphael’s Parnassus. Noting that both Ingres’s Apotheosis and Delacroix’s Luxembourg ceiling descend from the Parnassus, Henri Zerner justly concludes that “the work of Delacroix seems to us today much closer to the spirit of Raphael than that of Ingres.”57

More than ever before, Delacroix depicted civilization as the product of great geniuses whose achievement had little or nothing to do with social or historical circumstances. Unlike Ingres, Delacroix viewed artistic originality as far less beholden to the past or the present, but he shared with Ingres a vision of artistic greatness as the product of individual genius. The murals in the Library of the Bourbon Palace at times depict creative individuals embedded in their societies. The Luxembourg ceiling, like Ingres’s Apotheosis, isolates them from their historical contexts and emphasizes their belonging to a single continuous tradition. Delacroix still alludes to the vicissitudes of civilization (by including warriors, political martyrs, and some morally ambiguous figures such as Hannibal and Julius Caesar) and to the power of law to impose order (by including Orpheus and various statesmen). But now he no longer characterizes civilization as a historical process in a constant struggle with barbarism. Instead, he presents civilization as a roster of individual achievements, as an imaginary meeting of great minds, an escape from the actual world into a sort of heaven populated only by great individuals. Delacroix lamented in just these years, as we saw in chapter 1, that art offered less and less, after the Renaissance, the sort of “luminous Elysium fields” that allowed the soul to soar “above the trivialities and miseries of real life.” The Luxembourg ceiling provided precisely the spiritual, supernatural escape from the present that Delacroix felt was lacking in contemporary art. It is civilization as a dreamworld.58

The ceiling has rightly been praised for how well it succeeded with a very difficult setting: Delacroix had to work with a shallow, relatively low, and poorly lit dome. Illustrations cannot do justice to the way in which he used color, tonality, the sky, the landscape, and the pose and placement of figures to create a unified, decoratively interesting surface across the dome. Lee Johnson has observed that “the singing, unifying harmony of bright and limpid color with a Veronese-like splendor” suggests a mastery of monumental painting superior to that in the Palais Bourbon.59 Hannoosh has described how artfully the arrangement of the figures moves the viewer’s attention around the dome.60 While the murals in the Deputies’ Library certainly respond to their setting, here Delacroix fully explores the decorative possibilities of the architectural support. Indeed, the phenomenological experience of the dome is so pleasurable and engulfing that it supersedes, perhaps even undercuts, an intellectual exploration of its iconography. Thoré hits the nail on the head when he notes how the ceiling makes the viewer “dream and forget”: “[A]t the sight of this simple and majestic painting, like everything that is great, [and] this calm and majestic landscape, you feel in your soul an indescribable serenity and an enthusiastic aspiration toward the ideal; you are transported above deceptive realities into the only world where the mind finds satisfaction through poetry. M. Delacroix has in this way reached the goal of his art, which is, according to us, to inspire feelings and not to formulate abstract ideas.” The painting suggests an escape from this world, but not so much into the ideas of classical humanism as into an ethereal world of pure poetry and sensuality, conveyed, for Thoré, by color as much as anything else. Thoré concludes, “M. Delacroix has the rare merit of being a painter who is a painter, and who does not go elsewhere seeking means foreign to his art.”61

Subsequent murals relied still more heavily on decorative effects. For the Apollo Gallery Delacroix turned once again to Ovid, selecting the episode from book I of the Metamorphoses in which Apollo, surrounded by his fellow gods, battles Python (fig. 18).62 This was the most general of allegories: light versus dark, good versus evil, order versus chaos. The ceiling’s open-endedness is evident in the variety of interpretations it has elicited: it has been understood as a representation of the triumph of enlightenment and knowledge over ignorance and superstition, as the victory of revolution over democracy, and as a dream of an eventual victory of Louis-Napoleon’s dictatorial politics over democracy or socialism.63 Delacroix may have considered at least some of these possible meanings at one time or another.64 It seems unlikely, however, that Delacroix intended his painting to be read primarily as a political allegory: it offers nothing to fix its meaning for the public; it lacks sufficient specificity and reference to the present to have clear political significance.

FIG. 18 Eugène Delacroix, Apollo Slaying Python, 1850–51. Oil on canvas, 800 × 750 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris. Inv. 3818.

Delacroix undoubtedly saw the ceiling in part as a return to the theme of civilization and barbarism: the opposition between light and darkness and the battle of Apollo and the serpent, a creature of the primeval slime, were common allegories for the opposition between civilization and barbarism. On one preparatory drawing, Delacroix described the swamp creatures at the bottom of the painting as “ignorance, barbarism—blind furor,” and on another as “Calibans.”65 In comparison to the Deputies’ Library, however, civilization and barbarism are here defined only in the most abstract of terms. Perhaps Delacroix’s pessimism about any ultimate victory of civilization over barbarism is signaled in the uncertainty of the outcome of the battle, as Hannoosh has emphasized.66 This was in the immediate wake of democratic revolutions, when Delacroix was particularly scornful of the notion of progress, as he indicates in his journal. But in such a vague, open-ended allegory, the characterization of civilization and barbarism could have nothing of the nuance of the Deputies’ Library.

In the Bourbon Palace, Delacroix’s aversion to modernity and the idea of progress had led him away from the present and away from narratives of national triumph, back to the intellectually rich world of humanism, but he still engaged directly with theories of civilization and the political associations of his site. In the Apollo Gallery his flight was far more complete: while he was still developing philosophical ideas out of his textual source, he was more concerned with responding to his location in the Louvre. This was less an escape into ancient literature than an escape into the history of art. The Apollo ceiling is above all else an exercise in the decorative effects of mural painting, and more specifically a response to the art of Charles Le Brun, who had painted much of the rest of the ceiling. Le Brun had intended the five compartments that run down the center of the ceiling to represent the progress of the sun (Apollo) across the sky over the course of the day. He completed three of them, and Antoine Renou executed a fourth, though one of these, Le Brun’s Aurora on Her Chariot, was in such poor condition that it had to be re-created as part of the restoration of the gallery. The enormous middle compartment, which Delacroix executed, would have shown the sun at its peak, but Le Brun’s exact plans remained unknown. Delacroix provided a reasonable substitute with his Apollo Slaying Python.67

There is no question that Delacroix saw his work in the Apollo Gallery as a sort of competition with Le Brun, who was still commonly considered, with Nicolas Poussin and Eustache Le Sueur, one of the three great painters of seventeenth-century France. He wrote to a friend, “This is a very important work, which will be set in the most beautiful place in the world, beside beautiful compositions by Le Brun. You see that the footing is slippery and you have to hold on firmly.”68 Just before its completion, he made clear what was at stake: “What I am finishing right now is a big deal for me: people are watching me to know definitively if I am a painter or a hack.”69 Another artist might have tightened up when asked to compete with one of the most revered mural painters of the seventeenth century, but for Delacroix the challenge had just the opposite effect. He worked very much in the idiom of Baroque allegories, but loosely and inventively, placing robust, classical bodies throughout the space, lending them weightless, endlessly varied poses, employing dramatic color contrasts across the composition, using dramatic shifts in scale and tonal contrasts to create deep recesses into space, and animating the surface with rich brushwork.

The ceiling relies on Delacroix’s study of the Old Masters, which was particularly intense at this moment. He took the first of his study trips to Belgium in July and August of 1850 and focused especially on Rubens. Delacroix had been building his figures up from halftones, but he noted that Rubens relied far more on rich impasto, strong tonal contrasts, and firm contours to strike the viewer. He translated these observations into practice in the Apollo ceiling, and he also drew on Rubens’s energetic poses and muscular bodies. For example, Hercules and the marvelously grotesque demon standing next to him come straight from Rubens.70 The tiger and to some extent Python draw upon the beasts in Rubens’s Reconciliation of Marie de Medicis and Her Son.71 Veronese also provided a major example, both for his use of simplified tonal contrasts to model bodies and for his facility posing the body. The figures of Juno, Vulcan, and Victory all have sources in Veronese.72 The number of sources and the ease with which they are incorporated into the final composition suggest that Delacroix was not burdened by the weight of tradition but in fact eager to use the ceiling as an opportunity to employ and play with the art of the past.

He focused on the decorative aspects of the commission. Each god strikes a distinctive pose, and each is clothed in a distinctly different color, transforming the upper half of the painting into a sort of idiosyncratic spectrum. Delacroix’s facility in freely disposing the human form in space and making it appear to float is especially evident in the putti around the center, whose varied forms are richly modeled with pinks and blues. There are many places where the imagery echoes or plays off the shapes of the surrounding frame and stucco work: compare, for example, Hercules and the winged demon in the lower right to the figures in the stuccowork below them.73 In the lower half of the painting motifs are manipulated to maximize their graphic effects. Note the fantastically coiled serpent with its scaly belly, blood pouring from its wounds and fire spewing from its maw (fig. 19); the grotesque demons in the lower right, near Hercules, and in the sky just to the left of center; the tiger seen from below as it spills over the waterfall, its body stretched across the lower left of the composition, echoing the shape of the picture frame. Significantly, the parts of the ceiling that are most visually stunning or sensually painted are located as much in the barbarous hell as in the civilized heavens, and in minor as well as major figures. The primal, untamed world below provided the same possibilities as the enlightened gods above for magnificent visual spectacle. The visual interest of the painting supersedes its narrative purpose, offering an aesthetic appeal quite apart from its moral lesson.

FIG. 19 Eugène Delacroix, Apollo Slaying Python, 1850–51 (fig. 18), detail. Paris, Musée du Louvre. Inv. 3818.

Some sense of Delacroix’s changing conception of painting is revealed in a letter he wrote to Alfred Dumesnil in 1850. Dumesnil was requesting tickets to see the ceiling of the Gallery of Apollo and praised Delacroix’s work in the Library of the Bourbon Palace. Delacroix, according to Dumesnil, was inaugurating “a new era for French art” by introducing “landscape” and “a heroic, popular instruction” into mural painting. Delacroix had remained “the great colorist that Europe admires,” as was appropriate for mural painting. Dumesnil praised in particular The Chaldean Shepherds (see fig. 83) for revealing “the new faith”; he had never imagined anything “more simple, more religious.” “It is the greatness of God, the infinite of creation, just like that which modern sciences are revealing.” Dumesnil’s interpretation, however quirky, is suggestive insofar as he imagined Delacroix providing a new public art based not on the lessons of classical humanism but on a spirituality found in color and nature. Delacroix responded in terms that were typical of the ways in which he had begun to discuss art in his journal in the 1850s: “I don’t doubt that your imagination has added more [to my work]. It is in any case one of the properties of painting to open a field to thought that is freer, or at least vaguer, than that of poetry: like music, it [painting] lets each individual contribute his own share and think in his own manner.”74 This might be read as a polite dismissal of Dumesnil’s interpretation, but Delacroix had been exploring vagueness as a particularly admirable attribute of painting, one that arose from unique attributes of the medium, such as color and facture, and that contributed to the especially uplifting imaginative experience painting could have on its audience. The ceiling of the Gallery of Apollo had in fact moved in this direction.

The ceiling was Delacroix’s greatest critical triumph, inspiring numerous commentators to label it a masterpiece and him the nineteenth century’s greatest painter. Critics were well aware that when most contemporary painters turned to ceiling painting, they were peculiarly inept at making their figures appear to float in the air—Ingres was a case in point—so they were justly surprised by Delacroix’s success in this regard. Like no other painter of his day, he embraced the grand tradition of mural painting as an arena in which he could successfully compete with past masters. As a large-scale decorative work and as a sophisticated play on the tradition of Baroque mural painting, the ceiling is unquestionably a triumph. But as a comment on civilization, it has little to say. Beyond its art-historical references, the painting offers no examples of civilizational greatness, no means for comparing the present to the past, no comment on progress or any other idea that relates civilization to modernity. The ceiling marks a definitive shift away from a critical engagement with the social aspects of civilization, foregrounding instead the historicist and formal aspects of Delacroix’s practice. The painting suggests that its achievement is something measured against a more or less autonomous history of art, and this is how critics interpreted it.75 Much of this may have been in the nature of the commission, especially its location in the Louvre and the fact that Delacroix had only one large image with which to work, but his mural painting in general was shifting away from the allegorical complexity of the 1840s.

This conclusion is borne out by Delacroix’s last major mural cycle for the government, the ceiling of the Salon de la Paix in the Hôtel de Ville. This was another enormous project, consisting of a central circular painting approximately five meters in diameter surrounded by eight paintings in oblong coffers measuring 1.05 × 2.35 meters. There were also eleven lunettes, each 2.35 meters long at the base, between the cornice and the ceiling. Unfortunately the decorations were destroyed when the building burned in 1871, but its iconography can be reconstructed from descriptions, sketches, and reproductions.76

The large central painting, entitled Peace Descends to Earth and known from a sketch (fig. 20), depicted a weeping Earth, posed much like the central figure in Greece on the Ruins of Missolonghi (Musée des beaux-arts, Bordeaux), looking to the heavens for aid. Her clothes are bloody, but the battle has passed: a soldier puts out a torch with his foot, relatives and friends separated by the fighting embrace, others gather up the bodies of the fighting’s victims. Above, Peace appears amid the Muses, Ceres pushes back Mars, Discord flees, and Jupiter threatens evil-doing divinities.

FIG. 20 Eugène Delacroix, sketch for Peace Descends to Earth, 1852. Oil on canvas, diameter 77.7 cm. Musée Carnavalet, Paris.

The exact origin of this subject remains unclear, but the government may have dictated it to the artist. One critic, Gustave Planche, with whom Delacroix had viewed the ceiling before its public unveiling, indicated that this was the case.77 Another, Louis Clément de Ris, read it as an allegory of the condition of “France, after civil conflicts, imploring Peace, who descends from the sky bringing Abundance with her.”78 He also referred to the fighting as a “civil war,” and Théophile Gautier saw “civil conflicts” in the painting as well.79 This could only mean that they saw it as an allegory for the state of the nation after the revolutions of 1848; the rise of Louis Napoleon had brought Peace and Abundance. The subject unquestionably relates to the name of the room—Salon of Peace—chosen by the government after Louis-Napoleon’s coup d’état to signal its promise to end civil strife.

A political interpretation may well have been what the government had in mind, but again, Delacroix’s use of allegory was so vague that, unsurprisingly, most critics offered no such precise reading. The subject matter of the rest of the murals was still more generic. The eight surrounding coffers represented Mars in chains and seven gods friendly to peace: Ceres, Bacchus, Venus, Mercury, Neptune, Minerva, and Clio. The lunettes portrayed eleven subjects from the life of Hercules. These were all very traditional subjects, lacking any clear reference to the historical moment. Hercules’s various feats rendered him “a tamer of monsters and protector of the oppressed,” as Gautier put it, but he may or may not have been referring to Napoleon III.80

It is still possible to see civilization and barbarism in the opposition of peace and war. Planche even saw it allegorized in the life of Hercules, but this probably says more about how closely the theme was associated with major public mural projects than it does about Delacroix’s cycle.81 Delacroix himself complained about the subject matter. In a letter to Planche, he said, “It is ridiculous to see nothing at the Hôtel de Ville that recalls the Hôtel de Ville. Mars, the Muses, Napoléon in the clouds [which Ingres had painted on a ceiling in another room] have in effect nothing in common with what goes on in a municipality, and one could devote a good part of the decorations to this subject.”82