Observations about animals and the emotions they inspire punctuate Delacroix’s journal. Once, when walking in the forest near his country house in Champrosay, he chanced upon a fight between “a fly of a peculiar species and a spider.” Victorious, the fly sucked the spider dry and dragged him away “with an unbelievable liveliness and fury.” Delacroix’s commentary continues: “I watched the little Homeric duel with an odd emotion. I was Jupiter contemplating the battle of Achilles and Hector. What’s more, there was distributive justice in the victory of the fly over the spider. For so long we have only seen the opposite happen. This fly was black, very long, with red marks on its body” (510).

Delacroix’s desire to read a human narrative into a fight between an insect and an arachnid—and nothing less than a key episode from the Trojan War—suggests much about his fascination with nature. He reveled in nature’s variegated details, observing the form and behavior of the animals like a zoologist, but he was also inclined to find very human allegories in the struggles of animals, in this instance an example of distributive justice! There was something primal about nature that took him back to Homer, who for him, as noted earlier, represented a primitive, elemental world free of the triviality and banality of modern life. The spider and the fly fought with a passion and purpose worthy of Greek heroes. But as much as they were like Achilles and Hector, they were also puny, making Delacroix feel like Jupiter. As he gazed upon the battle, he was at the same moment a boy amusing himself in the outdoors, a naturalist, a humanist, a political philosopher, and a god.

Animals held a central place in Delacroix’s art and thought throughout his career.1 Approximately one-fifth of Delacroix’s paintings devote substantial attention to them. Study sessions in stables, zoos, traveling menageries, and natural history museums were a lifelong practice. Horses fascinated him, as they did so many artists of his generation, and he frequently drew birds, reptiles, crustaceans, and domesticated animals of all kinds. Within this very diverse menagerie, however, ferocious beasts stand out, lions in particular. This chapter argues that pictures of lions, especially in hunts, provided Delacroix an opportunity to explore emotions he felt toward modern civilization. I suggest that the great Lion Hunt now in Bordeaux took aim at the ideals of industrial and technological progress celebrated in the Exposition universelle de 1855, where it was first shown. More generally, his hunt paintings give loose metaphorical form to ideas and intuitions Delacroix had about civilization. They picture a world of maximal conflict and competition, things that Delacroix felt in his more misanthropic moments were just as present in human society as in the animal kingdom and that characterized modernity as much as any other period. And yet they also conjure up a world filled with passion, spontaneity, simplicity, and directness—qualities he valued in art and felt were disappearing from the world. In this sense they constitute another sort of primitivism.

Delacroix was capable of depicting lions and tigers with excruciating naturalism. One of his first major paintings of felines, Young Tiger Playing with Its Mother (fig. 48), received deserved praise for its lifelikeness when it appeared in the Salon of 1830. Throughout his career, however, he associated lions and tigers with the expressive possibilities of rapid execution and abstracted form. For example, in a drawing from 1851 (fig. 49) of a lion attacking a boar, the violence of the subject is conveyed especially by the quality of the line. Rapid, gestural, heavily drawn lines emanate out from the point where the lion bites into his prey. They describe his mane, but their function is just as much to mark the center of the violence and suggest its energy through their vigorous forms. The marks are especially dense around the jaw and claws of the lion, where, instead of clearly recording details, they communicate the emotional charge of the carnage through their urgency, spontaneity, and insistent reworking. The swift calligraphic strokes, the simplified composition of two parallel bodies together forming a simple lozenge, the scribbled, loose definition of form—all these things provide graphic equivalents for the speed and immediacy of the visceral action. Animals, and particularly animal violence, often seemed to demand an abstracted technique.

FIG. 48 Eugène Delacroix, Young Tiger Playing with Its Mother, 1830. Oil on canvas, 131 × 194.5 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris. RF 1943.

FIG. 49 Eugène Delacroix, Lion Attacking a Boar, 1851. Red chalk on paper, 19.9 × 30.8 cm. Kunsthalle Bremen—Der Kunstverein in Bremen, Department of Prints and Drawings. Inv. Nr. 1974/627.

During the last fifteen years of his career, Delacroix pursued his interest in lions, tigers, and other ferocious beasts in numerous paintings of the hunt, and these too elicited from him a high degree of formal experimentation. For example, his Lion Hunt in Boston (fig. 50) creates a gap in the center of the composition, between the lion, horses, and men in the foreground, that extends back to the distant lioness, whose unusual body—seen as if from above—extends along the vertical axis. The lioness’s body establishes a flattened, decorative pattern down the center of the canvas, reminiscent of the effects found in Ukiyo-e prints. On either side the curving shapes of men and horses form two roughly symmetrical groups, with the weapons of two horsemen creating a V in conjunction with the central lioness. Below, a lion and man form a centralized pyramid that is framed by the horsemen. The spatial effect is bizarre, as the distant lioness is pulled forward into the overall surface design. There are numerous similar paintings of hunts from the final decade of the artist’s life. Ultimately this chapter attempts to explain the connections between the theme of the hunt and the daring formal experimentation to which it gave rise in Delacroix’s art.

FIG. 50 Eugène Delacroix, Lion Hunt, 1858. Oil on canvas, 917 × 1,175 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. S. A. Denio Collection—Sylvanus Adams Denio Fund and General Income. 95.179.

I begin by considering the general significance of ferocious beasts for Delacroix—the range of their meanings and their ubiquity in his work—before singling out two meanings that are of special significance to his thoughts on civilization: lions, tigers, wolves, and their like embodied the barbaric aspect of man that for Delacroix always existed under the veneer of civilization, and they simultaneously stood in positive ways for an existence outside the constraints of civilization. The animal and the human were closely connected for Delacroix. Hundreds and hundreds of drawings, from his earliest childhood sketchbooks to his dying days, explore seemingly every possible interaction between humans and animals, from peaceful coexistence and domesticity to erotic relations and fatal combat. He often used his drawings to imagine fantastic creatures with both human and animal features, sometimes in childlike doodles, sometimes in physiognomic studies, and sometimes in drawings begun from nature or the work of other artists. In a drawing from around 1828 (fig. 51), meandering lines of wash form the heads of humans in some places and those of a horse and a lion in others, as if in a daydream he moved from one to the other. In some of his major paintings Delacroix depicted his protagonists with the features of animals.2 On the border of the first state of a lithograph depicting an episode from Goethe’s Faust in which Mephistopheles introduces himself to Martha, he drew felines that seem to embody the malevolent intentions of Mephistopheles.3 All these images suggest that Delacroix saw the human in the animal, the animal in the human.

FIG. 51 Eugène Delacroix, Sheet of Studies, possibly late 1820s. Ink on paper, 22.6 × 18.1 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris. RF 10606.

In the late 1820s and 1830s, Delacroix developed this interest in close collaboration with Antoine Barye, who was establishing himself at the head of a new school of zoological sculpture. The two artists shared a great deal, but Delacroix’s peculiarly anthropomorphic view of animals separated him from Barye. In contrast to most artists specializing in natural history, both Delacroix and Barye were attracted to ferocious predators seen in moments of extreme violence, both used animals to create compositions filled with curvilinear, intertwining forms, both sometimes pictured battles between species that in nature would never confront one another, and both dissimulated the circumstances in which they actually observed animals—in captivity, where they were often in ill health or dead—in order to suggest a completely untamed world. But Barye kept naturalism as a prime concern, remaining true to his hard-won understanding of the anatomy of animals, and he portrayed a whole range of exotic predators. Indeed, animal painters in France of the 1830s and 1840s pursued primarily a detailed naturalism concerned very much with the distinctive features of individual species. Delacroix developed in a very different direction.4

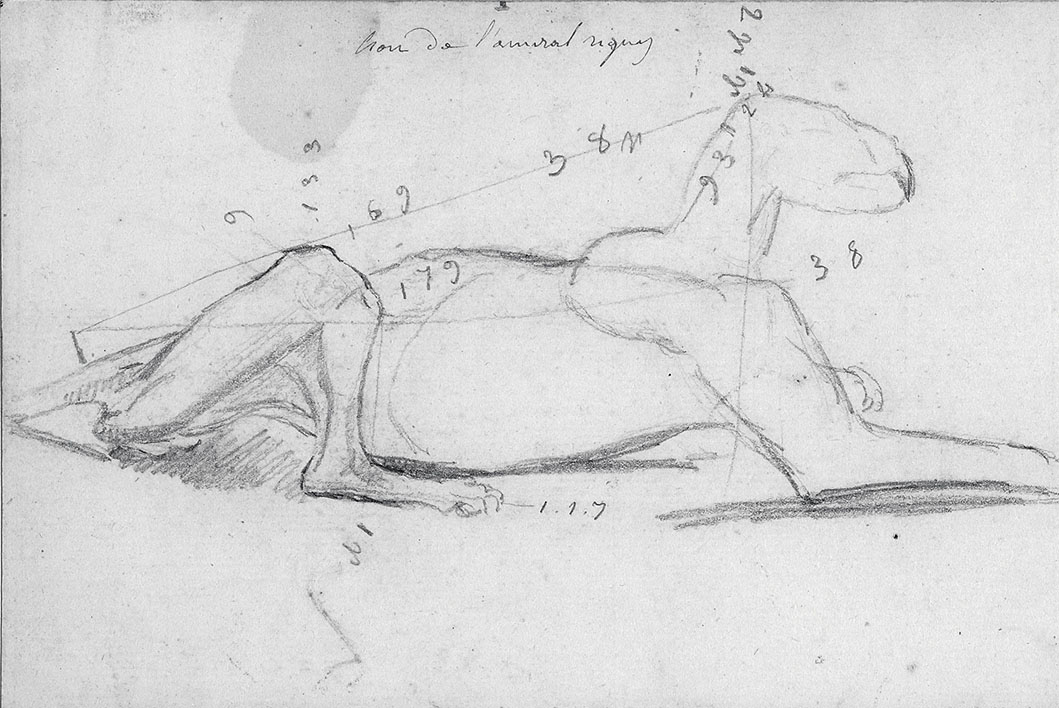

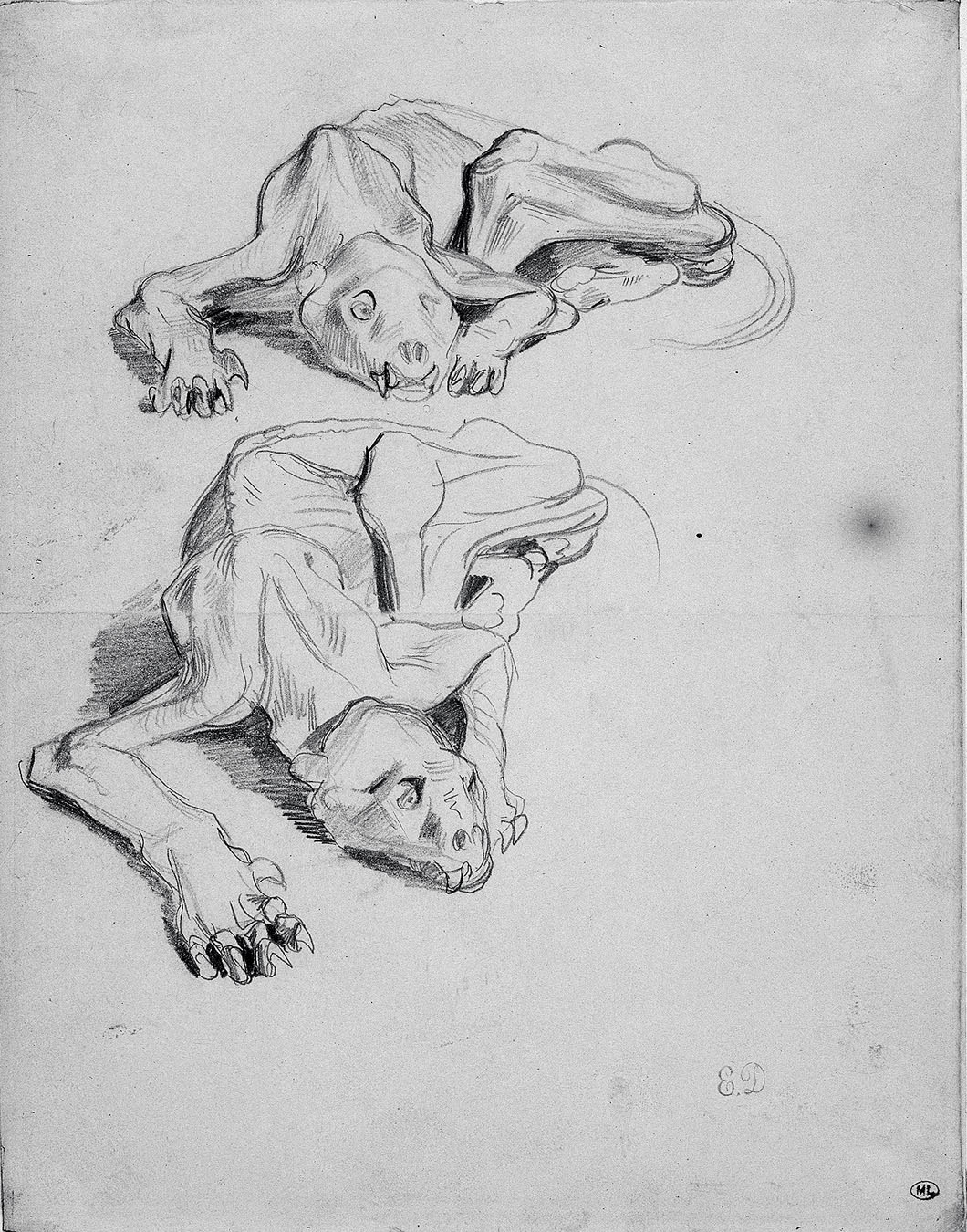

Delacroix’s difference from Barye can be seen in drawings of a dead lion that each did in 1829 at the Museum of Natural History. Delacroix had gotten word that the lion was headed for the dissecting table, and wrote excitedly to Barye to come with him to draw it.5 Barye used the opportunity to execute a number of careful anatomical studies, complete with measurements of angles and distances (figs. 52 and 53). Such precise drawing was typical of écorchés, or studies of skinned animals, because the exercise permitted a more exact understanding of muscles and bones under the skin. Delacroix, in contrast, worked with dramatic, varied contour lines and deep shading, making the lion seem almost human and alive.6 For one drawing he depicted the corpse in a pose analogous to that of a bandit in an earlier painting (figs. 54 and 55).7 Many years later Delacroix described this drawing session to Hippolyte Taine, who summarized the conversation as follows: “What struck him most was that the back paw of the lion was a monstrous human arm, but twisted around and reversed. According to him, there are thus, in all human forms, more or less perceptible animal forms to be disentangled, and he added that in pursuing the study of these analogies between animals and man, one discovers in the latter more or less perceptible instincts that link his intimate nature to one animal or another.”8 In her study of Delacroix’s images of lions and tigers, Eva Kliman has noted how Delacroix again and again likened the forelegs of lions to the arms and hands of men in pictures from the 1830s to the 1860s.9

FIG. 52 Antoine Barye, The Lion of Admiral Rigny, 1828. Pencil on paper, 13 × 25.2 cm. École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts, Paris. EBA509-062.

FIG. 53 Antoine Barye, The Lion of Admiral Rigny, 1828. Pencil on paper, 13 × 24.7 cm. École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts, Paris. EBA509-063.

FIG. 54 Eugène Delacroix, Two Studies of a Dead Lion, 1829. Pencil on paper, 24.9 × 19.2 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris. RF 9690.

FIG. 55 Eugène Delacroix, Wounded Brigand, 1825. Oil on canvas, 32.7 × 40.8 cm. Kunstmuseum Basel. Inv. 1726.

Around 1847 Delacroix’s animal paintings began to focus primarily on violence between wild predators or on men hunting or fighting with lions and tigers. He used animals to picture a world of generalized aggression, a kind of “war of nature” or “battle of life” in the parlance of the period. In this regard he shared his period’s growing tendency to view nature as a world of all-out competition—a view that, beginning in the late eighteenth century, would crystallize in phrases such as “the struggle for existence” and “the survival of the fittest.”10 It is important to remember that such ideas were very much under discussion long before they were given their most compelling and famous form in Darwin’s On the Origin of Species in 1859 and explicitly connected to human society in the 1860s by Darwin, Herbert Spencer, and others.11 In particular, Thomas Malthus’s Essay on the Principles of Population, first published in 1798, likened competition between humans to the struggle of plants and animals for survival. Such analogies became common in studies of both nature and human society.12

Delacroix lived in a golden age of natural history—in many ways one that has continued right down to our own time—when understandings of the relationships between humans and animals were changing rapidly. As Diana Donald notes, “Thinking about the implications of affinity and difference became more interrogative and open-ended.”13 Already in the eighteenth century Linnaeus had classified men among the animals; Lamarck and others proposed that humans “evolved” or “descended” from other species. Such theories prompted intellectuals to debate with renewed vigor the ways in which animals were like and unlike man in terms of reason, language, learning, emotion, and social evolution. Humans appeared to dominate nature as never before, but on the other hand, new scientific theories questioned the notion that humans were fundamentally different from or superior to animals. Natural history suggested that the appearance and disappearance of species bore no relation to divine or human purposes, that human dominance was of recent origin, and that nature operated with indifference to humans. The very existence—amoral, self-interested, and cruel—of vicious animal predators seemed to indicate that competition and destruction were natural conditions of life.14

As noted in chapter 1, Delacroix pursued similar ideas in his journal: “The world was not made for man”; “Man dominates nature and is dominated by it” (839). He insisted once at a dinner party that man was part of the animal kingdom and governed by instincts not unlike those of beasts (780). The field of natural history fascinated Delacroix. He devoted two of the twenty pendentives in the Bourbon Palace Library to naturalists, and six of the other paintings depict animals. In his journal one sees him emulating the procedures of naturalists in the field, noting down possibly unknown species or recording the detail and diversity of the natural world.15 The journal reveals a deep familiarity with the writings of Buffon, and he was personally acquainted with the two leading French naturalists of his day, Georges Cuvier and Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire.16 Delacroix’s interest in natural history was not, however, technical or scholarly. In his writings on the subject he expressed no opinion, for example, about the famous controversy between Cuvier and Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire before the Académie des sciences in 1830 on the possibility of organic transformation and the relation of zoological forms, key questions that preceded that of the origin of species.17 He maintained this silence although he knew Cuvier and Geoffroy personally and although major writers in his circle, including Balzac and Sand, engaged in the debate.18 Rather than scientific issues, it was the affective qualities of animals and the metaphysical issues they raised that dominated his thought.

Images of vicious predatory animals fighting in nature or with men gained much greater currency in the nineteenth century. The phenomenon appears precociously in the second half of the eighteenth century in English art, which served as an important source for Delacroix’s own ideas. He copied or closely reworked images by George Stubbs (fig. 56) and James Ward (fig. 57) and may well have known the work of James Northcote (fig. 58).19 Writing about such images, Alex Potts has suggested that the nineteenth century’s “preoccupation with representations of wild animals . . . testifies to a growing preoccupation with [the violence of social being in bourgeois society]. The new imagery of a wild nature provided a vivid symbolic language in which to conjure up and dramatize the idea of a world governed by elemental conflict and raw instinct.”20 Similarly, Donald comments, “Many thinkers were becoming aware, not only of the extensive parallels between the behavior and social organization of men and animals, but of the degree to which this commonality was made evident in a condition of perpetual struggle between competing interests, in which the weakest went to the wall. Artists of the time provided an imaginative embodiment of these institutions, which may well have influenced scientists.”21 This was true in France as well, though such analogies became common at a later date. Balzac’s Comédie humaine was conceived explicitly in these terms: the series of novels was, according to the author himself, a “natural history” that likened social classes to zoological species and used animal metaphors to describe both individual and group conflicts in contemporary society.22 Moreover, Nancy Finlay has shown that it was common in the 1840s to compare human violence and social conflict to struggles between animals.23 Competition between humans was increasingly likened to competition in the animal world.24

FIG. 56 George Stubbs, Horse Attacked by a Lion, 1768–69. Oil on panel, 25.7 × 29.5 cm. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, New Haven. B1977.14.71.

FIG. 57 James Ward, Lion and Tiger Fighting, 1797. Oil on canvas, 101.6 × 136.2 cm. Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

FIG. 58 James Northcote, Tiger Hunt, 1806. Mezzotint with etching (proof impression) by W. T. Annis, from the painting exhibited in 1804, 58 × 65 cm. Royal Academy of the Arts, London. 07/1663.

Whether or not the rise of this subject matter in Romanticism is attributable to the emergence of sociological and economic models that emphasized competition, self-interest, and fitness, there can be no question that Delacroix sometimes saw in animal violence a metaphor or allegory for struggle in human society. One entry in his journal begins by describing a peaceful village at night: “I saw the moon floating tranquilly over dwellings apparently plunged in silence and calm. The stars seemed to hang in the sky over peaceful abodes.” Suddenly, however, the tone changes: “The passions that inhabit them, the vices and crimes, are only sleeping or staying up in the shadow and preparing arms. Instead of uniting against the horrible evils of mortal life in a communal and fraternal peace, men are tigers and wolves pitted against one another in a battle of mutual destruction” (625). There follows an extended description of various types of maleficent men who surround the few “noble and generous” ones.

At another moment he meditates on the proposition that “man is a sociable animal who detests his own kind.” After defending the idea, he concludes, “The crimes one sees committed by a crowd of unfortunate people living in the state of society are more horrible than those committed by savages. A Hottentot, an Iroquois, chops off the head of the person he wants to skin; with cannibals, they cut someone’s throat in order to eat him, like our butchers do with a sheep or a pig. But these perfidious, carefully planned plots, which hide behind all kinds of veils, of friendship, of tenderness, of little kindnesses, are only seen in civilized people” (613). Delacroix apparently found his imagined savage preferable to civilized man because he was supposedly less dissembling and more frank in his motives. The Iroquois and Hottentots would find better defenders than Delacroix, whose anthropology was deeply misanthropic, but the point is that Delacroix saw a ruthless animal existing under a veil of civility.

In still another of his maudlin ruminations, Delacroix contemplates “the many degrees of what we agree to call civilization.” After the passage cited in chapter 1 in which he asserts that “barbarians are not found only among savages” but also in Europe, and goes on to criticize the “new barbarism” of modernity, he compares men to animals: “If man is [God’s] work of predilection, why abandon him to hunger, to the filth, to massacres, to the terrors of an uncertain life next to which that of animals is incomparably preferable, despite the anxiety, the fear, of having to hunt for prey, analogous torments but made lighter by the absence of this intelligent spark that still shines through the most horrible human muck” (1204). In this instance the state of animals was preferable to that of men because they could at least not reflect on their miserable state.

The foregoing suggests a second, very different way in which ferocious animals appealed to Delacroix: in addition to offering a metaphor for social conflict, animals allowed him to envision an existence outside the constraints of social life. In particular, they allowed him to imagine a world free of that great bane of modernity, ennui (as noted in chapter 1): “Animals don’t feel the weight of time. They have no other worries than material life. The savage himself doesn’t know what ennui is; he barely senses a distant danger. Repose is for him the supreme good; he does little if he isn’t pressed by need, and doesn’t look for entertainment to fill the moments that he is not sleeping or hunting his prey. This carefree life is the true life of nature. It is civilization, on the other hand, that created all the arts destined to console man or delight him” (1809). This passage ends in paradox, as civilization simultaneously robs man of his carefree state and consoles him for this loss, but civilization nonetheless brings with it ennui. Closely related is a common image in Delacroix’s writing, and indeed in Romantic artistic theory generally: inspiration was like a wild animal that allowed the genius to escape from convention.25

Animals not only helped Delacroix to imagine a life lived free of social constraint and ennui, they also provided a cure for his own ennui. There are numerous places in his journal where the sight of animals, or simply the experience of nature, provides Delacroix with a kind of release from his everyday cares that leads directly to a heightened state of awareness. Here he is, for example, after seeing a flock of sheep awaiting the butcher: “What sympathy I feel for animals! How these innocent creatures touch me! What variety nature has put in their instincts, their forms that I am constantly studying, and how much she has let man become the tyrant of all this creation of animated beings living the same physical life as him” (755). Again and again Delacroix reveled in the escape nature provided him from the triviality of his everyday life.

It was exactly this sort of experience that inspired Delacroix, after a visit to the Museum of Natural History on 17 January 1847, to buy a notebook and recommence his journal after a fifteen-year hiatus.26 That day he was bowled over by emotion as he walked through the galleries: “Entering into this collection, I was struck by a feeling of happiness. As I advanced, this feeling grew; it seemed to me that my being lifted itself up above the vulgarities and petty anxieties of the moment. What prodigious variety of animals and what variety of species, of forms, of purpose” (326). Clearly the sight of animals provided a source of happiness, but it also negated “the vulgarities and petty anxieties of the moment.” After reviewing all the various exotic stuffed animals on display, Delacroix made a similar point about the overall effect of the museum:

________

Where does the emotion that the sight of all that produced in me come from? So that I left behind my everyday thoughts that are my entire world, and my street that is my universe. How it is necessary to shake oneself from time to time, to get outside, to try to read into creation, which has nothing in common with our cities and the works of man! Such a sight definitely leaves one better off and tranquil. Leaving there, the trees received their share of admiration, and they played a part in the feeling of pleasure that this day gave me. (327)

________

The shift from stuffed animals to living landscape seals the effect of liberation through nature. The sight of animals allowed him to leave behind the humdrum of everyday life and “the street” that was “his universe.” This last image juxtaposes his life in the modern city with his experience of the natural history museum. Various types of experience elicited similar sensations of release from Delacroix: great art and music, his voyage to Morocco, and increasingly moments in nature, especially during walks near his country house in Champrosay. But the sight of animals produced intense sensations of pleasure that rivaled any of these.

It was at approximately this time that Delacroix began to paint pictures of predatory animals—boars, serpents, crocodiles, and especially lions and tigers—with increased regularity. He painted no more than seven or eight pictures of this type before 1847, but some fifty afterward. The animals appear either alone or in combat, never in peaceful coexistence. Besides depicting lions in pictures of the hunt, he occasionally depicted them attacking their natural prey, but more often he staged battles between lions and other predators (e.g., fig. 59). These curious paintings are apparently attempts to imagine a world given over completely to aggression, violence, and survival.27

FIG. 59 Eugène Delacroix, Lion Attacking a Tiger, 1860–63. Oil on canvas, 49.5 × 56 cm. Oskar-Reinhart Collection “Am Römerholz,” Winterthur.

It has been suggested that Delacroix may have produced many of these paintings at the behest of his dealers, but the evidence points to a simpler explanation: Delacroix was obsessed with the subject matter.28 Many are small in size and painted with broad, loosely hatched strokes: they are intimate works that do not always seem entirely finished. Their private nature is also suggested by the fact that he gave many of them to close friends and fellow artists as gifts, perhaps because he had them on hand, and by the fact that he kept many for himself.29 He used drawings, watercolors, and pastels of felines for similar purposes.30 Thus, while his dealers were more than happy to sell his pictures of hunts and wild animals, sometimes asking for such pictures explicitly, the subject matter seems to have grown primarily out of his personal artistic interests. He turned to this subject matter in moments of self-amusement in which the physical act of creation joined up with his meditations on animals, when his fascination with savage beasts and his passion for painting became one and the same thing.

In 1854 Delacroix had the opportunity to take his interest in lion hunts in a new, far more public direction. The French government, seeking to show off the national genius for painting, decided to honor four painters by displaying work surveying their entire careers in the exhibitions at the exposition universelle planned for Paris in 1855. The privileged artists were Decamps, Vernet, Ingres, and Delacroix.31 The honor came with a generously paid commission for a new painting whose size and subject were left entirely to the artist’s discretion. One might have expected Delacroix to choose a classical, religious, or literary subject for such a prestigious picture; instead, he made the unusual decision to paint a lion hunt on a grand scale, over two and a half meters tall and three and a half meters wide.

His journal reveals that he threw himself entirely into the project, going to work on it the day after receiving the commission on 20 March 1854. Numerous preparatory drawings record his experiments with individual figures and groups. There appears to have been a period of discouragement in August, but on 21 November 1854, when he went back to the painting, he noted, “I am going to put it, I think, on the right path” (864); and on 7 February 1855, after observing that he had been working hard for fifteen days, he wrote, “I had already given the Lions the turn that I think, finally, is the good one, and I only have to finish it, changing as little as possible” (884). He was still working on the painting just weeks before his retrospective opened, because on 14 March 1855 he noted, “I took a break from my relentless work on the Lions to go at one o’clock to see the exhibition gallery” (886). The painting had been a major effort, and he was deeply invested in it.32

Tragically, a fire destroyed the upper third of the painting in 1870, and a subsequent restoration left it in its sorry present state. Only the bottom third is from Delacroix’s hand (fig. 60). The work’s overall appearance, however, is evident from a magnificent sketch (fig. 61) and a painting that may have served as a modello (fig. 62). In a turbulent but tightly organized composition, five men in fanciful oriental dress—three on horseback and two on foot—fight with a lion and a lioness. One of the men has already succumbed, while the lion mauls another. As the lioness sinks her teeth and claws into the hindquarter of a horse, the riders above are about to pierce her and the lion with spears. The action occurs in the very foreground of the picture, behind which a rugged verdant landscape extends into the distance.

FIG. 60 Eugène Delacroix, Lion Hunt, 1855. Oil on canvas, 175 × 359 cm. Musée des beaux-arts, Bordeaux.

FIG. 61 Eugène Delacroix, Lion Hunt, 1854. Oil on canvas, 86 × 115 cm. Musée d’Orsay, Paris. RF 1984-33.

FIG. 62 Eugène Delacroix, Lion Hunt, 1855. Oil on canvas, 54 × 74 cm. Nationalmuseum, Stockholm.

The painting’s horrific subject and exuberant style met mostly with incomprehension in 1855. While some of Delacroix’s most loyal supporters in the press defended him, the painting’s brilliant color, churning composition, and pronounced facture confounded most critics, and they rejected the painting in no uncertain terms, referring to it, for example, as clumsy, incomprehensible, confused, affected, unreal, and garish.33 Maxime Du Camp said that it “defied criticism. . . . This is almost raving madness, even harmony is neglected, for all the tones have similar values.”34 Perhaps because of its badly damaged state, it has received only modest attention from art historians since. Perhaps, too, because we see the painting in retrospect, after the daring formal innovations of avant-garde painting of the later nineteenth century, we tend to view its stylistic eccentricities as relatively tame. It was, however, a major statement of the artist’s aesthetic ambitions as he approached the age of sixty, a public manifestation of ideas that Delacroix had been developing privately for some time. At the Exposition universelle de 1855, the painting offered an implicit critique of the exhibition’s celebration of civilization, progress, and modernity.

A full understanding of this critique, however, must recognize the extent to which the painting adopted an archaizing, historicist rhetoric. It was obviously a tribute to Rubens. Delacroix had seen the Rubens hunt in Bordeaux (now destroyed) and possibly the one in Rennes (Musée des beaux-arts), but he knew Rubens’s hunt pictures especially through prints (fig. 63). His painting drew directly on the Flemish painter’s looming compositions, fanciful costumes, exaggerated grimaces, and gory detail. Many individual motifs are inspired directly by Rubens: the gestures for thrusting a lance or stabbing with a sword, the dramatic poses of fallen men, the rearing horse, the frightful ways in which the lions sink in their teeth and claws. Delacroix’s nervous, broken facture in the modello, which he translated into thick unblended strokes in the final picture, offered his own equivalent of Rubens’s exuberant handling.

FIG. 63 Schelte Bolswert and Peter Paul Rubens, Lion Hunt, late sixteenth to early seventeenth centuries. Print on paper, 26 × 36 cm. Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Bequeathed by Rev. Alexander Dyce. DYCE.2271.

Rubens had held a prominent place in Delacroix’s personal pantheon since the early days of his career; Delacroix formed his mature style as much in response to Rubens as anyone else. His journal reveals that he was constantly thinking of the Flemish master in the late 1840s and early 1850s. He had done numerous copies after Rubens in the 1820s, and he seems to have returned to the practice with some regularity in the 1850s, an unusual decision for an established artist in his full maturity.35 His drawings after Rubens are legion and come from throughout his career. In 1841 he painted a large copy of Rubens’s Miracles of Saint Benedict, which is astoundingly faithful to the original, even with Delacroix’s more fractured, agitated application of paint. In August of 1850 he had made a sort of pilgrimage to Mechelen, Antwerp, and Brussels in order to study the Baroque artist’s paintings firsthand, taking copious notes that focused in particular on technical procedures such as the way in which Rubens built his painting up from halftones. The voyage was marked by moments of ecstatic appreciation—much like the sort of enrapturing experience familiar from his accounts of animals, Morocco, nature, and great art and music. Hortense de Querelles once saw one of Delacroix’s Moroccan paintings at a gilder’s shop and later told the painter that it “transported her like music, made her heart race.” Delacroix took this as the highest compliment and said he experienced the same thing “before sublime [paintings by] Rubens” (448). His admiration for the Old Master—for his stunningly sensual handling, brilliant colors, and dramatic muscular forms—went hand in hand with his desire to escape through art from what he perceived as the banality of modern life. This was all part of the broader turn in his career toward tradition—the same impulse that transformed his ceiling in the Apollo Gallery into a homage to decorative mural paintings of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. His paintings in the modes of past masters were in part efforts to capture and reproduce the effect that great art of the past produced in him, and in that sense they were an implicit protest of the condition of modern art.

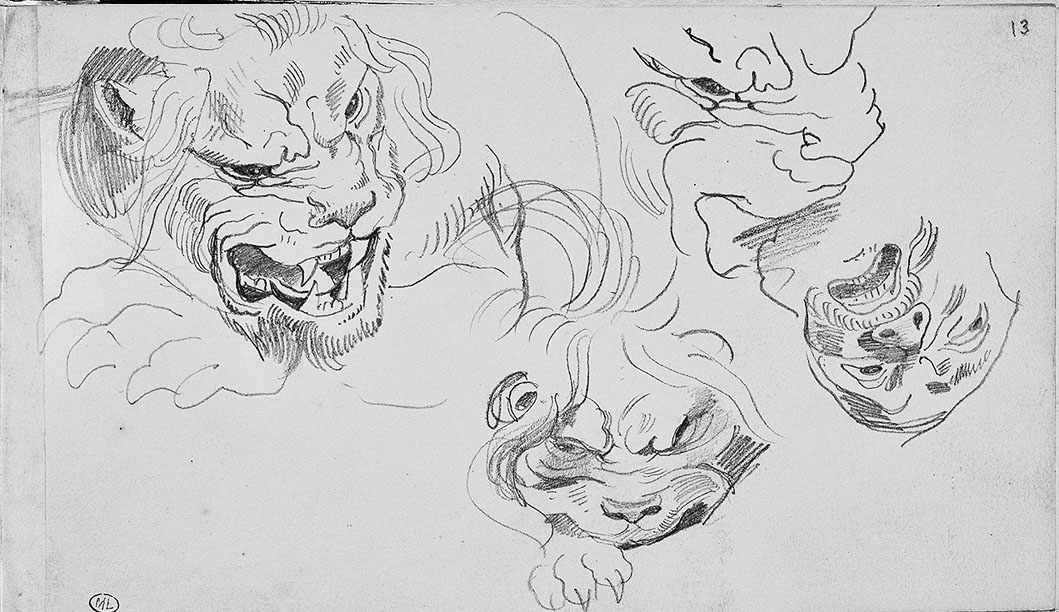

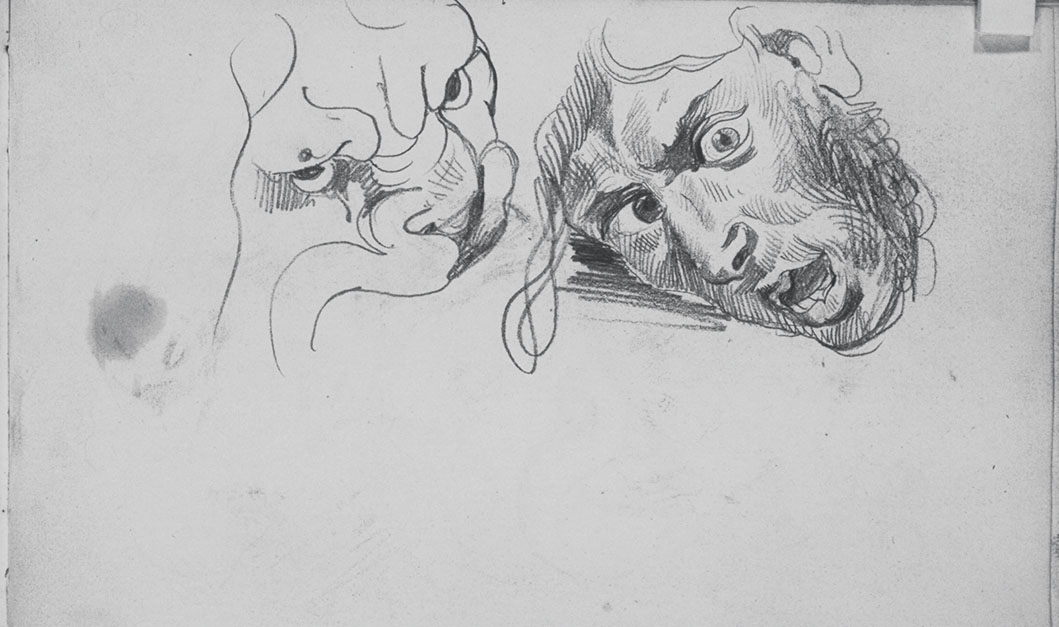

Delacroix admired Rubens’s hunts partly for the connections they made between men and predatory animals. In several drawings after engravings of Rubens’s hunts (e.g., figs. 64 and 65), Delacroix zeroed in on the enraged physiognomies of the men and animals, using firm curving contour lines to capture the curl of lips, baring of teeth, and furrowing of brows. Curiously, he isolated and juxtaposed the faces of the men and animals, and he made the human faces resemble those of the lions, far more so than in the original engravings. These are extraordinary documents because they suggest the extent to which Delacroix used drawing to explore and make concrete his ideas about the affinities between ferocious beasts and men.36 But Delacroix also felt that Rubens revealed how to use form to communicate something about animals and the hunt. In 1847, when Delacroix was contemplating the strange “feeling of happiness” that the gallery of stuffed animals in the Museum of Natural History had produced in him, he thought in particular of a hippopotamus he had seen and wrote, “Strange animals. Rubens rendered it marvelously” (326). Six days later he wrote an extended passage on two engravings after Rubens (figs. 66 and 67), one of a hippo and crocodile hunt and the other of a lion hunt, that reveals a great deal about his own interest in the subject. On the face of it, Delacroix noted, one would expect the lion hunt to be the more electrifying image because its iconography was far more horrific. He pointed to the lance bending “as it drives into the chest of the furious beast” and to the lion turning “with a horrible grimace toward another combatant laid out on the ground, who, in a final effort, sticks a frightful dagger into the body of the monster” (333). Delacroix enumerated many other hair-raising details. This was in direct contrast to the hippo hunt. The imagery in this etching benefited from the presence of a crocodile, “but its action could have been more interesting.” The featured creature—the hippopotamus—was “a shapeless beast that no execution could make tolerable.” The action of the dogs was “very energetic,” but Rubens, Delacroix noted, had repeated this idea many times before (333).

FIG. 64 Eugène Delacroix, Studies After Rubens’s Lion Hunt, ca. 1854. Pencil on paper. Musée du Louvre, Paris. RF 9144, 22 (fol. 13r).

FIG. 65 Eugène Delacroix, Study After Rubens’s Lion Hunt, ca. 1854. Pencil on paper. Musée du Louvre, Paris. RF 9150, 15 (fol. 8v).

FIG. 66 Pieter Claesz. Soutman after Peter Paul Rubens, Hippopotamus and Crocodile Hunt, ca. 1640. Print on paper, 47.3 × 64 cm. Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Bequeathed by Rev. Alexander Dyce. DYCE.1989.

FIG. 67 Pieter Claesz. Soutman after Peter Paul Rubens, Lion Hunt, ca. 1640. Print on paper, 48.2 × 65.5 cm. Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Bequeathed by Rev. Alexander Dyce. DYCE.1988.

And yet, paradoxically, and much to his surprise, the picture of the lowly mud-dwelling hippo affected him much more. The compositional design of the lion hunt lacked sufficient clarity, and there were too many details: “the view is confusing, the eye doesn’t know where to engage. It has the feeling of an awful disorder.” In the hippo hunt, on the other hand, “the manner in which the groups are disposed, or rather the one and only group, which forms the entire painting, shocks the imagination, and shocks it again every time one puts eyes on the painting, while in the Lion Hunt [the imagination] is always thrown into the same confusion of lines” (333). Delacroix’s discussion ends with a formal analysis of the hippo hunt, noting that its components are clearly organized into an X with the hippo at its center, that the prostrate man below the crocodile extends and anchors the composition at its base, and that the ample framing sky “gives the whole, through the simplicity of this contrast, an unrivaled movement, variety, and unity” (334).

Delacroix drew a clear lesson from this for his own art: the passion of the hunt was communicated as much by form as by subject or iconography. From the start he aligned elements within his hunt paintings to stress abstract geometric structure. Various elements—swords, limbs, bodies, even the contours of the landscape—line up on an axis or run parallel to one another to draw attention to surface design. Judging from the modello (fig. 62), the Bordeaux hunt displayed a rough symmetry in the overall grouping, thrown off only by the rider at the top right. Without him, the painting offers a neat pyramid with three men at its base, two lions in the middle, and a rider at the top. The undulating forms of the animals and men link them together into a single writhing mass, within which certain symmetries stand out. The curving form of the uppermost horse rhymes with the lioness on the right, and less so, though symmetrically, with the lion on the left. The weapons of the top two combatants run parallel to one another. The knife and musket at the bottom of the composition also run in parallel, and each is placed in roughly the same relation to the weapons at the top of the composition. Once noticed, the geometry of the composition is striking.

Composition was just one of many formal aspects of the picture in which Delacroix invested his energy. What remains of the final canvas reveals that he worked the surface richly, in places employing enormous hatched strokes, as for the bellies of the lions, and emphasized the dramatic contours of the figures. He amplified color contrasts and interwove colors, as in the marvelously painted blue, yellow, and brown rump of the horse on the right, or the yellow, blue, green, and white sleeve of the Arab in the center. He worked up the details of the costumes to further animate the surface. Notes that he made to himself in July reveal that he considered the various browns of the horses and lions to be key to the overall coloristic effects of the canvas (792). When he took up the canvas in November of 1854, he wrote, “Avoid black; produce obscure tones with fresh, transparent tones: either lake, or cobalt, or yellow lake, or raw or burnt sienna. After lightening the coffee-colored horse too much, I found that I improved it by reworking the shadows, particularly the pronounced greens. Keep this example in mind” (864). The shadows are in places indeed exceptionally luminous, as in the forearm of the fallen man in the lower left.

The Bordeaux hunt brought together various aspects of his art that he associated with release or escape from everyday life. The wild animals, the Orient, the impulsive violence, the transporting formal effects, and Rubens—by 1855 these all stood in Delacroix’s mind for richly sensual, immediate, all-encompassing, uncogitated experience. Perhaps this dense overlapping of themes and sources that Delacroix associated with emancipatory sensations explains the amazing sketch, the most energetic Delacroix ever painted and among the most stunning pieces of painting in his entire oeuvre. The fluidity of the painting is astounding, from the loose, exaggeratedly sinuous contours in brown that describe the figures to the curving gestural strokes that add color, sometimes from a heavily loaded brush, to the abrupt broad hatchings, like those beneath the lion or on the hind leg of the lioness or below the neck of the rearing horse, to the irregular scumbling that covers much of the background. The exuberant brushwork reinforces the turbulent movement and violence of the subject matter and amplifies the roiling forms of the composition. The colors are equally dazzling. For the shirt of the Arab in the lower center Delacroix used an unusual lilac hue and applied it generously and without hesitation. The same man’s wrapping is developed out of forest green and blue. Contrasting colors of red and green are used for the horsemen on the right and left. The rein of the fallen horse is little more than a squiggle of red and white strokes across the bottom center of the painting. Thick white highlights further animate the sketch. It was inconceivable at the time to exhibit such a sketch as a finished work, and something of its passion had necessarily to be lost in the painting exhibited at the Salon. Still, it suggests Delacroix’s desire to convey visceral emotions through the visual effects of painting, to connect painting to the raw, uncivilized, immediate emotions and actions of the hunt, to link the sensual pleasure of painting to primal, untamed experience.

The most immediate inspiration for the Exposition universelle de 1855 was the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, with its impressively massive and modern Crystal Palace.37 The Great Exhibition was first and foremost a celebration of commercialism and modern industry. “With this exhibition,” wrote Karl Marx in 1850, “the bourgeoisie of the world has erected in the modern Rome its Pantheon, where, with self-satisfied pride, it exhibits the gods which it has made for itself.”38 The fair’s promotional literature celebrated above all else civilization and progress in their most modern guise, and it inaugurated a tradition at such events of juxtaposing the marvels of industry with the material culture of the so-called primitive world.39 Traditional forms of high culture that resisted mass commoditization were neglected, sometimes completely: there was, for example, no category for painting, and sculpture and the plastic arts were integrated into the larger display. Pictorial representations figured only insofar as they decorated other objects or demonstrated technical processes. The exhibition blurred distinctions between the fine, decorative, and industrial arts and was devoted primarily to the promotion of the latter two.

The initial plan for the Exposition universelle, announced on 8 March 1853, also omitted painting and sculpture, but three months later officials added a fine-arts exhibition. After this initial oversight, the fine arts received their own impressive building, a Palais des Beaux-Arts that would stand adjacent to the Palais de l’Industrie. The government deemed that France led the world in the fine arts and sought in particular to vaunt the national genius for painting. But the fine arts nonetheless fit awkwardly into the exposition. While the rest of the fair celebrated a commercial, industrial, and technological future for the world, painting and sculpture often implicitly or explicitly paid tribute to the great artistic achievements of the European past. The fine arts also occupied a subordinate role in the fair. There were 2,175 exhibitors in the fine arts, 1,630 in agriculture and horticulture, and 21,779 in industry. Some of the largest official publications excluded the fine-arts exhibition, such as the Panthéon de l’industrie. Written by “men devoted to the progress of Civilization,” the guide characterized itself as “an archive” where future generations “will study the marvelous inventions of our epoch of progress.”40

As might be expected, the arts had to weather many unfavorable, even humiliating, comparisons to science and technology during the run of the fair. Listen to one Gustave Claudin: “The Aeneid and the paintings of Raphael are beautiful and sublime things that have rightly immortalized the names of those who conceived them; but if we had to make comparisons, we would place the electric telegraph above them. It seems to us that the inventor of this apparatus is, of all mortals, the one who has produced the most miraculous and surprising work. . . . The truth is that at present poetry and the arts are perhaps eclipsed by the discoveries of science and industry.”41 Following the lead of Maxime Du Camp, who had accused artists of “living in the past” in his review of the exhibition,42 Claudin ends with a call to poets to celebrate the modern and take on realist subject matter. He suggests they go to the Gallery of Machines in the Palais de l’Industrie for inspiration. Similarly, Édouard Gorges suggests,

________

Before the end of the century, industry will have—it is our profound conviction—realized the dream of the impotent papacy: universal domination.

Steam, electric communications, and free trade will produce, we have no doubt, universal peace and the fraternity of peoples.

In a word, industry is in our eyes the highest, the most complete, expression of modern civilization.43

________

Gorges goes on to observe that artists had fallen in the world since the disappearance of “grands seigneurs” and now found themselves condescended to by tailors, cobblers, and grocers. “To survive,” he suggests, “art will have to put its palette or inkwell in the service of industry.”44

“Civilization” and “progress” were the exposition’s watchwords, mentioned in virtually every guide and review. One, for example, called the exhibition “the most eloquent manifestation of progress” and suggested that it “plunged observers into a feeling that is much more like stupor than admiration.”45 Prizes were awarded for “outstanding contributions to civilization.”46 Inclusion in the exposition was itself a sign of membership in the civilized world. At the banquet for members of the international jury, a toast was made “to the prosperity of all the civilized peoples.”47 The exhibition promoted, according to one account, “the confederation of civilized countries.” While “each people applies progress with its own political and social forms,” the important point was that they “all walked down the path of progress toward the moral and material well-being of the masses.”48

Delacroix, as already noted, in his journal routinely ridiculed similar ideas about civilization, progress, and modernity. He was surely aware of the extent to which such ideas informed the exposition, because he was intimately involved in its planning. After the decision to include the fine arts, he was made a member of the Imperial Commission, which oversaw programming and procedures. He belonged to the international committee responsible for planning the fine-arts exhibition and to the admissions and awards juries. As a member of the Municipal Council of Paris, he participated in discussions concerning credits allocated to the project, its locale and building, and the organization of festivities, and he was honored with a retrospective within the fine-arts exhibition itself.49

In his journal he showed some impatience with the populist rhetoric of progress and commercialism surrounding the exposition. When in June he was “bothered” with a request to travel to London with the Imperial Commission to see the Crystal Palace, which had been dismantled and rebuilt in Sydenham, he scoffed:

________

These English have rebuilt one of their marvels, which they accomplish with a facility that astonishes us, thanks to the money that they find at just the right moment and to their commercial sangfroid, which we think we can imitate. They triumph over our inferiority, which will stop only when we change our character. Our exposition and our locale are pitiful, but, still another blow, our minds will never be transported by these sorts of things, where the Americans already surpass the English themselves, endowed as they are with the same tranquility and the same verve in practical things. (779)

________

Unlike the Exposition universelle, the Great Exhibition had been organized without government subsidies or loans, and this clearly rankled Delacroix. He was even more disturbed by the vanity and populism occasioned by the event. At a meeting of the municipal council he listened to members debate the guest list for an official ball welcoming Queen Victoria to the exposition. He mocked the pretensions of some of the shopkeepers and tradesmen on the council—to whom he referred as “all these grocers, all these housepainters, all these paper sellers, and all these well-heeled people”—as they worried about whom to include and whom to exclude. At the meeting Delacroix told them that “the French society of our days is made up only of these bootmakers and grocers, and you should not look at it too closely” (902). He grumpily disapproved of the “caprice” of the council in approving Baron Haussmann’s plan to cover the celebrated courtyard of Louis XIV at the Hôtel de Ville with a glass-and-iron structure and to add an entranceway for the visit of Victoria to the exposition (900). When the queen’s visit finally took place, Delacroix complained about the lack of coaches and the crowds. He went on: “You only run into trade associations, market women, girls dressed in white, all that with a banner in front and surging forward to offer a good reception. In fact no one saw anything, the queen having arrived at night. I felt sorry for all these good people who were going there with all their heart.” At the ball, Delacroix had to circle the Hôtel de Ville “two or three times to score a glass of punch.” He complained of “the terrible heat” and concluded, “What insipid gatherings!” (933–34).

The exposition itself did not fare much better. He described a meal he had on the grounds with bemusement, noting all that was vulgar, modern, and foreign about it:

________

I ate lunch like a real bourgeois, under a sort of trellis in a little café recently built in expectation of this public that comes so little to this glacial exposition, whose effect is spoiled, thanks to these disproportionate prices of five francs and even one franc, to which we are not accustomed. Contrary to my routine, I lunched very well on a piece of ham and a pitcher of Bavarian beer. I felt all happy, all free, all radiant, in this vulgar bouchon [Lyonnais restaurant], seated in the open air and watching the occasional gawker [badaud] going to the exposition.

________

Delacroix was bemusedly playing the part of the mindless consumer enjoying the sensual gratification on offer at an event that was patently organized to produce political complacency. He had various thoughts about the exhibition in the Palais des Beaux-Arts, but at the Palais de l’Industrie he was primarily scornful: “The sight of all these machines saddens me profoundly. I don’t like this stuff that seems, all on its own and abandoned to itself, as if it is [supposed to be] something worthy of admiration” (929). Afterward he visited Gustave Courbet’s “Pavilion of Realism,” which garnered a far lengthier and more enthusiastic, if somewhat confused, reaction.

One might have expected Delacroix to criticize the Palais de l’Industrie in stronger terms, given his deep loathing for all that it stood for, but perhaps his involvement in the planning of the exposition moderated his response. If he repressed his emotions in 1855, however, they came gushing forth the following year when he visited the gigantic Concours agricole universel, held in the Palais de l’Industrie. This exhibition unleashed an invective as harsh as anything else in the journal. Delacroix mocked the exhibition’s rhetoric of universal peace and the class of people he imagined that it most impressed:

________

All heads are turned; everyone admires all these beautiful imaginations: machines for exploiting the earth, beasts of all countries brought to a brotherly competition of all peoples: not one petit bourgeois who, leaving there, doesn’t think himself infinitely fortunate to have been born in such a precious century. For my part, I felt the greatest sadness in the middle of the bizarre meeting; these poor animals don’t know what this stupid crowd wants from them, they don’t recognize the random guardians assigned to them. As for the peasants who have accompanied their cherished beasts, they are lying down near their students, casting nervous glances at the idle strollers, careful to forestall the insults or the impertinent annoyances that they are not spared. (1020–21)

________

Delacroix was just warming to his subject. He asserted that modern breeding techniques were unnatural, compared modern farm machinery to “war machines” (“These are the engines of Mars and not of the blonde Ceres”), and expressed horror at the sight of new types of produce. In an extended aside, he lamented the rapidity of modern transportation, which he felt was destroying regional differences and rendering travel banal. Even Ottomans were now dressing like Frenchmen and attending French entertainments. These were exactly the observations that Karl Marx had made, from a very different perspective, when he critiqued the Great Exhibition.50

After several wildly sarcastic jabs at modern means of transportation, he segued into a critique of a future dominated by commercialism:

________

business will claim everyone when there are no more harvests to gather by hand or fields to watch over and improve by intelligent care. This thirst to acquire riches that will give so little enjoyment will have made of this world a world of courtiers. They say it is a fever that is as necessary to the life of societies as true fever is to the human body for certain illnesses, according to what doctors say. What is, then, this new illness that so many vanished societies did not know, societies that astonished the world with great and truly useful enterprises, with conquests in the domain of great ideas, with true riches employed to augment the greatness of states and to give more value to their subjects [à relever à leurs yeux les sujets de ces États]? (1023)

________

Delacroix finished by comparing modern civilization unfavorably to the ancient civilizations of Rome and Egypt. Just as the latter societies built dikes and canals against floods, Delacroix felt the modern world should have built dikes against “vile passions,” “cupidity,” “envy,” and “calumny,” and he finished with a rant against the press (1023).

I have quoted Delacroix’s jeremiad on the Concours agricole universel at length because it shows just how deeply he loathed modern celebrations of technology and commercialism. When these were juxtaposed with the worlds of animals, peasants, and traditional societies, as they had to be at an agricultural fair, he could barely contain his disgust. The spectacle of bewildered animals and peasants packaged into a diversion for the vulgar crowd infuriated him. But Delacroix went further: such celebrations neglected “great ideas,” contributed to the destruction of local, premodern cultures, and appealed most to a new class of people, the petite bourgeoisie, who were easily duped by its promises. He had articulated similar, if less vitriolic, thoughts at the Exposition universelle, where the celebration of progress, commerce, technology, and modern civilization had been equally intense. His most passionate expression of opposition in 1855 was, however, in his Lion Hunt: there he pictured wild animals and exotic Orientals engaged in a completely outmoded form of hunting that brought out their most unrestrained behavior. And he did it in a form that hearkened back to Rubens and the grand tradition of European painting—to the rich heritage that he felt modernity was displacing. Delacroix’s painting detached itself from the official ideals of the exhibition: if the latter celebrated progress, civilization, and peace, he chose tradition, archaism, the primitive, and violence. While the exposition claimed that modern society was characterized by every increasing harmony and well-being, Delacroix pictured a bestial aggression that he saw as ever present in humanity and just as characteristic of modernity as any other period. In opposition to the banal mass-cultural spectacle of the exposition, he provided a fantasy world of passion and spontaneity. In contrast to the celebration of a mastered nature and a society given over to the rhythms of commerce and industry, Delacroix imagined the excitement of an animalistic world filled with unpredictable, uncogitated action. His Lion Hunt could be considered a silent protest at the very center of the Exposition universelle, though one that went largely misunderstood. And yet, in his quest to provide a release from the exposition, he invested ever more attention to the formal possibilities of painting, pointing the way toward a new type of aesthetic experience.

Delacroix’s Lion Hunt pictured a world and offered a type of experience that contradicted the dominant rhetoric of civilization and progress surrounding the exposition of 1855. Like the artist’s Orientalism generally, it gave form to his negative reaction to modernity. But also like Orientalism—indeed, even more so—his desire to find, through immersion in the subject, a release from the banality and triviality of modern life—to imagine through them a more primal, vital mode of existence—had to contend with the fact that such fantasies were themselves the stuff of many new popular modes of representation. Ferocious beasts were present in Paris as never before, in zoos, traveling menageries, and animal shows, and accounts of frightening encounters with them proliferated in images, newspapers, books, and popular media of all sorts.51 The prevalence of his subject matter in the most pedestrian popular culture meant that Delacroix had to establish a difference between it and his own work if the latter were successfully to suggest an escape from the here and now. In this final section I argue that his sophisticated formal innovations and engagement with art history offered him two ways of doing so.

Delacroix studied lions, tigers, and other ferocious beasts primarily at the zoos, traveling menageries, and animal shows proliferating in nineteenth-century Paris.52 Such spectacles traded on a fascination with rapacious animals, but they did so in conditions that ultimately emphasized human dominance and sometimes even compassion. As Éric Baratay and Élisabeth Hardouin-Fugier note, “Big cats were . . . the focus of great interest, because they symbolized wildness and cruelty (they were always suspected of being man-eaters) and encapsulated both the fear of nature and the satisfaction of having overcome it.”53 Leading animal painters, especially in England, sometimes made animal shows and similar events the stuff of their art (e.g., fig. 68), but for Delacroix to achieve his image of violent combat outside the bounds of civilization, he necessarily had to erase his reliance on these spectacles.54 In contrast to the domination or domestication of wild animals emphasized in most popular spectacles, Delacroix used wild animals to imagine an existence completely outside the bounds of civilization.

FIG. 68 Sir Edwin Henry Landseer, Isaac Van Amburgh and His Animals, 1839. Oil on canvas, 44.5 × 68.5 cm. Royal Collection, Windsor Castle, London.

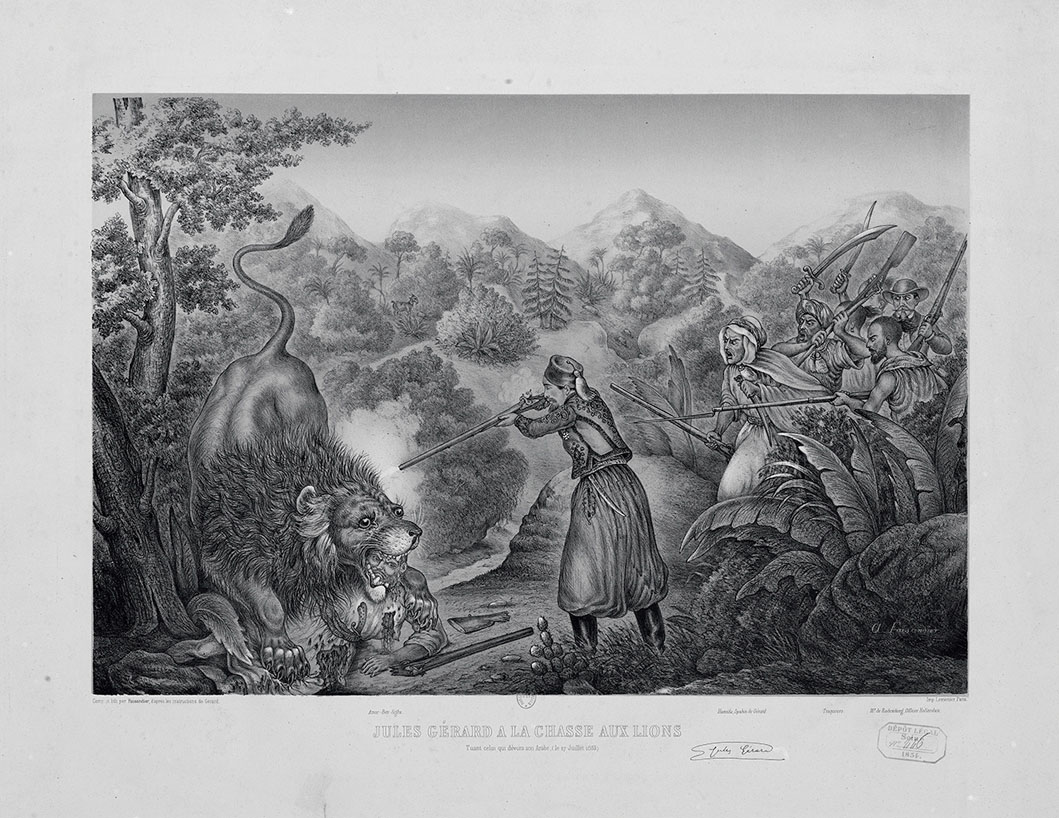

Similarly, Delacroix’s hunts coexisted with a burgeoning adventure literature featuring the hunt. The best-known chronicler of the hunt was far and away Jules Gérard, a big-game hunter also known as “the Lion Killer” (fig. 69). In 1854 he published his astonishingly successful book Lion Hunting, whose fifteenth edition appeared in 1901.55 Gérard was a plainspoken man of action with little time for literary ambition. As he says in his book, “I don’t pretend to be a stylish man: I warn those who will read these few chapters that they won’t find sentences, but observations based on experience, anecdotes, and facts told simply and just as they happened.”56 He was a man’s man who, as one early biographer claimed, had to be convinced to take up the pen between cigars.57 His account makes the colonial circumstances of his adventures explicit: the French rendered a service to Algeria by ridding it of lions, and in return they gained the respect of the colonized. At one point Gérard enumerates the rewards of lion hunting: the successful lion hunter acquires a “perfect indifference to death . . . , then the esteem, the affection, the recognition, and more from a multitude of people who will remain hostile to your country and your religion, and finally memories that will make you feel young in your old age.”58 One of the chief qualities possessed by a successful hunter, according to Gérard, was his rugged masculinity. As he puts it, “The lazy one, the sybarite, the effeminate hunter, can glean close to the cities and campsites; the disciple of Saint Hubert will take the rich harvest far away, very far away, in the mountains and in the plains.”59 Gérard often represented the Arabs he met as infantile, ignorant, and badly in need of his aid, but when he singled out some for praise, it was usually for their manliness.

FIG. 69 Auguste Faisandier, following instructions from Jules Gérard, Jules Gérard Hunting Lions, Killing the One That Ate His Arab (27 July 1853), 1854. Lithograph. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

Something of Gérard’s attitude toward both the hunt and indigenous Algerians is captured in advice he offers to prospective lion hunters on how to introduce themselves to Arabs:

________

The man that you might describe as talkative is thought poorly of by Arabs. You can be foolish, stupid, it’s respectable to be a thief or an assassin, but it is shameful to run at the mouth. . . .

Answer few questions, and always with modesty.

They will say: —Is it during the day or at night that you hunt lions?

You will reply: —Day and night.

—Alone, or accompanied?

—Alone.

Then you will tell them:

—I come from France to hunt the lion, because he does you much harm, and because to kill him is to do good, and also because, in the lion hunt, there is always the danger of death, and we French love to confront death in order to do good.60

________

The condescension and machismo hardly need to be pointed out, but evidently they only increased Gérard’s popularity.

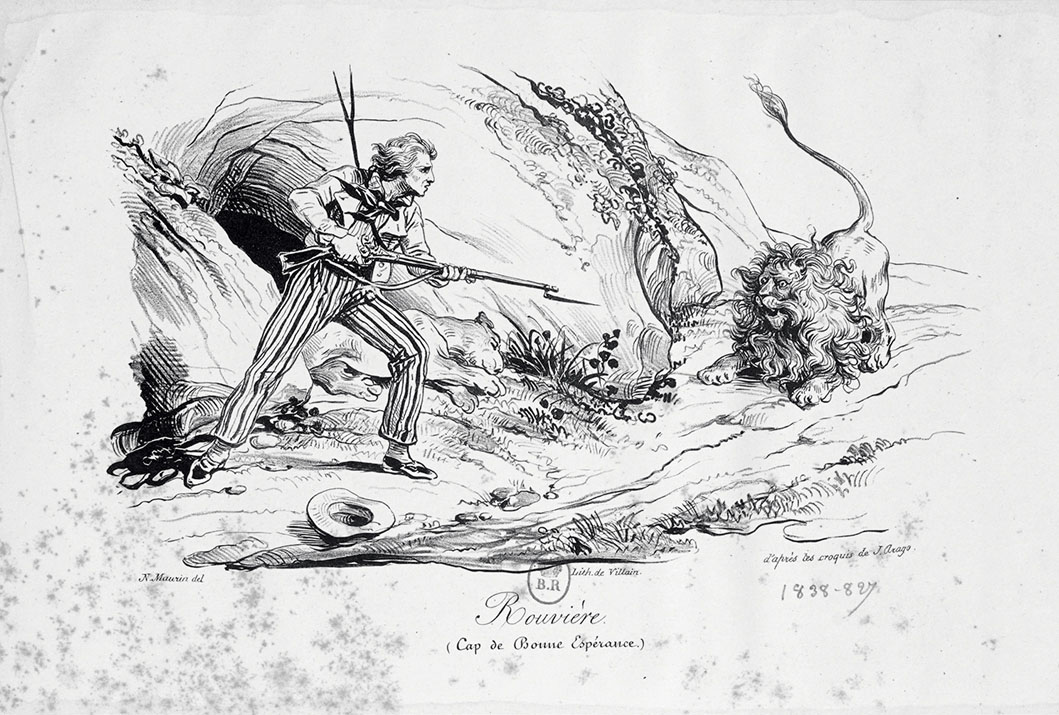

Delacroix noted the appearance of one of Gérard’s articles in his diary in 1854 but said nothing about it.61 An unkind appraisal of Delacroix’s hunts might emphasize all they share with Gérard’s: both men depicted the hunt as a harrowing, especially masculine affair set in the Orient. Yet the comparison should also highlight the efforts Delacroix made to cordon off his work from popular culture and the contemporary world. Gérard located his narrative in a specifically colonial context and constantly asserted French national superiority. His anecdotal style emphasized the banalities of his particular time and place and drew attention to his own personality, with its marked sexism, jingoism, and almost absurd virility. Delacroix increasingly removed his hunts not only from the colonial world but also from any realistic world. In one of Delacroix’s earliest hunt paintings, he offered a view of man stalking a lion with a gun, and he returned to a similar subject in 1854 (fig. 70).62 These pictures set the lion deep within the pictorial space and place viewers just behind the hunters, allowing the viewers to engage in the unfolding narrative of the hunt much as they would if reading Gérard’s stories. Such an arrangement was common in popular depictions of the colonial lion hunt (e.g., fig. 71). But these are exceptional paintings within Delacroix’s oeuvre, and he moved away from this imagery permanently in 1855. His hunters wear a fanciful oriental dress that defies precise ethnographic placement, and they pursue such ill-advised tactics as attacking lions at close quarters with swords or knives, thus often ending up in frightening wrestling matches with their prey. The overt, exaggerated references to Rubens located Delacroix’s late hunts as much in art history as anywhere else. Gautier went straight to the point when he said of Delacroix’s 1855 Lion Hunt, “We don’t know what Jules Gérard would say about this method of attacking lions.”63 Delacroix’s hunts took their distance not only from zoos, animal shows, and natural history museums but also from representations of hunts in the contemporary colonial world.

FIG. 70 Eugène Delacroix, Arabs Hunting a Lion, 1854. Oil on canvas, 74 × 92 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg. GE-3853.

FIG. 71 N. Maurin after a sketch by J. Arago, Rouvière, 1838. Lithograph. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

As with Orientalism generally, the lion hunt would soon find itself the subject of mockery within advanced art. In 1863 the vastly underappreciated novelist Alphonse Daudet began to lampoon the outmoded masculine and exoticist ideals embodied in the lion hunt in a series of short stories that culminated in Tartarin de Tarascon, first published in 1872. The novel follows the exploits of a small-town hero obsessed with Orientalist tales of adventure, including those of Jules Gérard. He travels to Algeria to hunt lions but finds instead an odd, hybrid society of North Africans and Europeans dominated by rogues and swindlers. After many misadventures—for example, on his first night of hunting he kills a much-beloved donkey in the suburbs of Algiers—he finally succeeds in bagging a lion, only to discover that the poor blind tame beast had recently been retired from the circus and was venerated by the local inhabitants. Daudet began publishing his spoofs of lion hunting in the same year that Delacroix died, but surely similar derision greeted Gérard’s accounts among some intelligent people from the moment they first appeared. Delacroix found himself in a representational field dominated by the most idiotic mass culture, even more so than other stock Orientalist subject matter.

The same problem existed with many of the central themes of Romanticism—for example, individualistic stories of adventure, episodes of excessive sexuality and violence, lurid tales of spectacular falls from social grace. Such narratives were taken up by artists of the grandest aesthetic ambitions at the very moment they were popularized by the most dimwitted hacks, but in the case of the lion hunt the contrast was particularly sharp: Delacroix turned to the subject exactly when a vulgar version of it had seized the nation’s attention. The eccentricities of Delacroix’s hunts—the absurd tactics, the exaggerated, staged violence, the abandonment of ethnography, the conspicuous reliance on Rubens—helped to separate them from popular versions of the same subject, but the separation was at best partial. Delacroix was in the end painting essentially the same subject as Gérard. However much his 1855 hunt may have been conceived in opposition to the ideals of progress and modernity on display at the Exposition universelle, Gérard’s version of the hunt demonstrated how easily the subject could be enlisted to serve those ideals.

Delacroix’s awkward position explains something, I think, of the increasingly eccentric formal qualities of his hunts after 1855, as in, for example, the one now in the Art Institute of Chicago (fig. 72). But while the Chicago painting draws attention to its own artifice, it nonetheless also offers a deep, illusionistic view of the subject. At a distance the illusion coheres marvelously: the combatants are arranged in a circle that winds back from the enormous lion in the foreground, through the groups on either side, to the foreshortened horseman in the rear. Joel Isaacson once likened the group to a merry-go-round, noting how it is inscribed in a circle (seen in perspective: an ellipse on the flat plane of the canvas) defined by the arcing area of dark in the extreme lower right corner, the dark, slightly curving ridge or shadow behind the central brown horse’s legs, and the prominent arc formed by, at left, the horse’s head and white-turbaned man’s head, arm, and curved sword, which almost complete the pattern.64 Delacroix even offers a sort of repoussoir in the form of a shoe in the immediate foreground that sets the rest of the composition in depth. Within this space one has no difficulty reading the illusion: claws tearing into flesh, weighty bodies leaping, falling, or energetically wielding swords and spears. The feeling of dreadful violence is amplified by the weightiness and corporeality of the bodies.

FIG. 72 Eugène Delacroix, Lion Hunt, 1863. Oil on canvas, 72 × 98 cm. Art Institute of Chicago, Potter Palmer Collection. 1922.404.

At the same time, many elements flatten the composition, which is most easily conceptualized as a lozenge, a shape reiterated by numerous subsidiary elements. Note, for example, the spear of the man on the left, which appears to run roughly parallel to the picture plane. It also aligns with the lower edge of the lioness and with the heads and bodies of the men in the lower group, drawing all these motifs into a single plane. The two adjacent sides of the lozenge are more loosely indicated by the spear of the topmost cavalier and the swords of the men at the bottom and on the right. Each corner of the lozenge is punctuated by an area of red that plays off the complementary color of green. The odd fleshy color of the fallen horse is echoed across the composition by the garment of the man on the right. The flamboyant forms in the clouds, the ridges of the mountains, the crests of the waves, and the edges of the windblown garments further emphasize surface design. All share undulating, irregular contours and highlighted edges emphasized with thick flourishes of impasto. There is a landscape in the picture, but its details are none too clear, nor is the relationship of the circular area where the hunt takes place to the surrounding environment established. Note the curious ridge that cuts down from the horizon in the upper right toward the foreleg of the uppermost horse: is it curling over like a wave, or should we appreciate it and the surrounding forms more for how their agitated shapes and handling animate the picture?

There are places in the Chicago Lion Hunt where formal and thematic concerns displace illusionistic procedures, particularly when the painting is examined at close quarters. The body of the fallen horse on the left suggests the animal’s anatomy well enough, but it is equally conceived as an undulating surface of sensuous contours that take on an interest in their own right (fig. 73). It is built up from carefully hatched strokes arranged into rows of color of varying values. Other passages, such as the saddle and blankets of the fallen horse on the left, are used as an opportunity to contrast a wide variety of hues (fig. 74). The visual interest of this area of the canvas is as much in the gestural notations and contoured surface as it is in the overall illusion. In other places correct anatomy is sacrificed for expressive effect (fig. 75). Thus the anatomy of the lowermost figure defies all sense of proportion. His left arm is impossibly large and connects in no clear fashion to his torso. His right leg is simply massive. Delacroix wanted to emphasize the comparison of the man’s hand to the lion’s paw: there are even touches of red around the man’s hand, as if it tears into the lion’s flesh in the same manner that the lion’s claws tear into his calf. A similar juxtaposition of hand and paw occurs just above, in the left forearm of the kneeling man and the right foreleg of the lion.

FIG. 73–75 Eugène Delacroix, Lion Hunt, 1863 (fig. 72), details. Art Institute of Chicago, Potter Palmer Collection. 1922.404.

Similar distortions, juxtapositions of color, and flattening effects can be found in any number of Delacroix’s late paintings and are again part of a general tendency in the late work to play illusion off of such things as brushwork, two-dimensional design, brilliant color, and other decorative effects. For instance, in a series of mythological paintings representing the four seasons, on which he was still working at the time of his death, Delacroix experimented similarly with sharply rising landscape motifs such as rocks, cliffs, clouds, and trees. These broad areas painted in somber tones loosely frame the figures, whose garments, in prismatic colors, animate the painting. In two of the paintings, Spring (fig. 76) and Winter (fig. 77), the negative spaces between the rising landscape elements stand out as shapes in their own right, each a band of pigments that cuts down through the center of the composition. The result is strikingly abstract. Many other examples might be provided. Delacroix was pursuing similar effects throughout his art, but in the hunt paintings they relate to his subject in unique ways.

FIG. 76 Eugène Delacroix, Spring: Orpheus and Eurydice, 1856–63. Oil on canvas, 198 × 166 cm. Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand.

FIG. 77 Eugène Delacroix, Winter: Juno and Aeolus, 1856–63. Oil on canvas, 198 × 167 cm. Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand.

On the one hand, they serve a variety of positive expressive purposes. Animals generated deep, immediate, nameless emotions in Delacroix, as well as extended metaphysical meditations on nature, humans, and society. Many of the idiosyncratic aspects of his animal paintings—distortions of anatomy and physiognomy, exceptionally loose, unconstrained technique, stunning color juxtapositions, rhyming, simplified compositional elements—are efforts to give form to feelings inspired in him by animals. But Delacroix’s formal innovations were also a negative response to the world in which he found himself working. As I have argued here, Delacroix’s choice of a lion hunt as the subject for the Exposition universelle was implicitly a negation of the ideals of progress and modernity that the fair promoted. The hunt he depicted was an outmoded social practice, and to portray it he turned back to an equally outmoded type of picture. The world he imagined was passionate and unconstrained, the very opposite of all he criticized in modernity. It was on the level of form, however, that Delacroix most clearly distanced his own production from competing representations of the hunt, especially those that situated it as a living practice in the colonial world. Delacroix’s hunts shared much with popular versions of the subject—their extreme violence, exoticism, and over-inflated masculinity—but Delacroix’s style disrupted the notion that the paintings depicted an actual hunt. The subject is there, it has a degree of depth and solidity, but it exists in an odd space between illusion and abstraction, a curious never-never land where art-historical reference and painterly effects count for as much as the illusion they create, where spontaneity, sensual emancipation, spiritual release are embodied as much in the achievement of the artist—the way he moves the viewer with his art—as by the illusion or subject.

The overall trajectory that Delacroix followed in the hunt paintings might be summarized as a series of renunciations and repudiations. From the start the subject had been a departure from the literary and historical themes expected in large-scale Salon painting—it was an overtly archaistic gesture that conjured up Rubens and a form of heroic, violent, hypermasculine imagery that had long since fallen into desuetude. In 1855 these ideals flew in the face of those celebrated at the Exposition universelle: progress, utility, civilization, modernity. It was, in short, a flight into the past. Animals and hunts were common motifs in a whole array of contemporary spectacles and representations with which Delacroix was extremely familiar, but he was at pains to distance his own paintings from them. He located his hunts in a largely imaginary setting separated off from actual hunting practices and from the colonial world where they took place—a flight into fantasy. Most strikingly, the hunt paintings became a site for formal experimentation—a flight into form—where expressive qualities of composition, color, and brushwork become superior signs for conveying spontaneity, passion, and rich, engulfing experience, in part because they separated his work from everyday experience and from representations of similar subject matter that Delacroix deemed inartistic. To be sure, Delacroix never envisioned a painting where the expressive aspects of the medium itself could be freed from illusionistic representation, and unlike later painters, he never renounced his connection to the grand tradition of illusionistic painting that for him began especially in the Renaissance. But his distance from other modern representations of the hunt had to be made clear, and establishing his distance from realistic representation proved to be an important means for doing so.