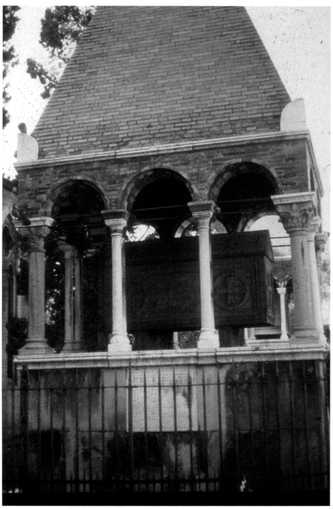

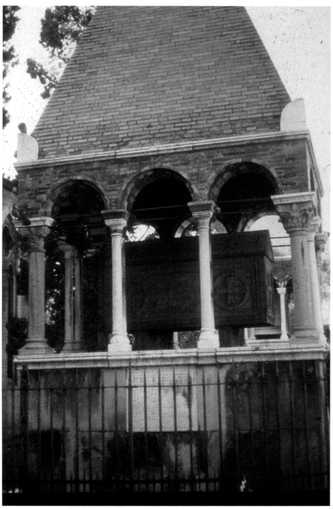

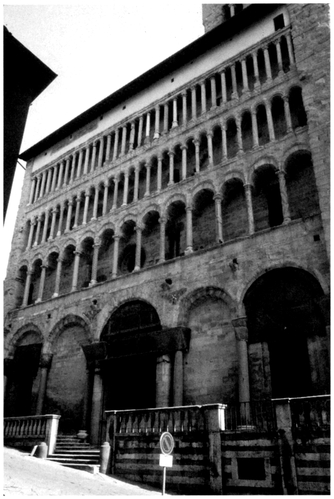

Tomb of Accursius, Bologna. Photograph courtesy of John W. Barker.

The Acciaiuoii, a great Florentine banking family, originated in Bergamo. They migrated to the Borgo Santi Apostoli, in the Florentine quarter of Santa Maria Novella, in the early twelfth century and obtained property in the Val di Pesa. The Acciaiuoii were popolani ("of the common people") and Guelf by political tradition, and they joined the Black Guelfs after the schism. Leone di Riccomanno, a doctor of law and one of Florence's fourteen buoniuomini of 1282, founded the bank and international commercial enterprise that soon ranked among the city's greatest. These businesses had branches throughout the Mediterranean and in England, France, and Germany. The Acciaiuoii served as papal bankers, and Acciaiuolo Acciaiuoii (d. 1341) began a fiscal and political relationship with the king of Naples that led to commercial monopolies, the post of seneschal for his famous son Niccolo (or Niccola, 1310-1365), and feudal lordships in Greece that the family finally lost in 1460 to the invading Turks. Angelo Acciaiuoii (1349-1408) rose quickly in the church to become bishop of Rapallo (1375), bishop of Florence (1383), and a cardinal (1385).

The bankruptcies of Edward III of England led to financial disaster for the family in Florence in 1345, and their fortunes and prestige never fully recovered, although they remained influential in the later trecento. Before that, however, they had been very active politically. Between 1282 and 1341, the family contributed seven standard-bearers of justice and five buoniuomini to the Florentine state and three consuls to the Calimala guild. From 1310 to 1342, family members served in the Signoria twenty-five times; Dardano di Tirigo (d. 1335), for one, was elected ten times between 1302 and 1334. Angelo Acciaiuoli (b. 1298) was bishop of Florence from 1342 to 1355 and was a leader in the overthrow of Walter of Brienne.

See also Acciaiuoli, Niccola; Florence

JOSEPH P. BYRNE

Becker, Marvin. Florence in Transition, 2 vols, Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1967.

Brucker, Gene. Florentine Politics and Society, 1343-1378. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1962.

Chrystostomides, J. Monumenta peloponnesiaca. Camberley: Porphyrogenitus, 1995.

Davidsohn, Robert. Storia di Firenze, 8 vols. Florence: Sansoni, 1956-1968.

Laberge, George A. "Select Documents Relating to the History of the Acciaiuoli (1319-1364) with Special Reference to Niccolo (1310-1365)." Ph.D. dissertation, Boston University, 1952.

Schevill, Ferdinand. Medieval and Renaissance Florence. New York: Harper and Row, 1963.

Tanfani, Leopoldo. Niccola Acciaiuoli. Florence: Le Monnier, 1863,

Ugurgieri della Berardenga, Curzio. Gli Acciaiuoli di Firenze nella luce dei loro tempi (1160-1834), 2 vols. Florence: Olschki, 1962.

The Florentine Niccola Acciaiuoli (1310-1365), a friend of Boc-caccio, became grand seneschal of the kingdom of Naples. Although writers sometimes refer to him as Niccolò, he himself used the spelling Niccola. He was born in the Val di Pesa to Acciaiolo Acciaiuoli and Guglielmina de' Pazzi. Although his father was of illegitimate birth, the Acciaiuoli, a family of Black Guelfs, were one of the most prominent lineages in Florence, with thriving commercial interests throughout the Mediterranean.

At eighteen, Niccola Acciaiuoli married Margherita degli Spini, and in 1331 he was sent to represent his father's business in Naples. He entered the service of Catherine of Valois-Courtenay, princess of Taranto; became her lover; and was sent to administer her lands in Greece (1338-1341), where he won for himself the barony of Calamata. After the death of King Robert of Naples, Acciaiuoli arranged the marriage of Prince Luigi of Taranto to Queen Giovanna, possibly after assisting in the assassination of Giovanna's first husband, Andrew of Hungary. In 1348, Acciaiuoli was named grand seneschal ("grand" to distinguish him from other seneschals) and count of Terlizzi; and, after Giovanna's flight to Provence and return to Naples, he helped Luigi to establish control over the kingdom. In 1349, he traded Terlizzi for the county of Melfi and was also named captain general of the duchy of Calabria. An unsuccessful attempt on his life by followers of the queen in 1350 was followed by the liberation of Giovanna by the Marseillais. Giovanna and her husband were being taken back to Provence when Acciaiuoli engineered their return. This proved definitive, and it put an end to the resistance of the queen's partisans. With Luigi of Taranto the sole holder of power, the grand seneschal in effect ran the kingdom. In 1354, he took back most of Sicily, although Messina resisted until 1356 and Catania held out successfully. Luigi of Taranto's defeat at the battle of Arcireale (20 June 1357) was unfairly blamed on Acciaiuoli by his enemies, but in 1359 Acciaiuoli was sent on a successful embassy to defend the kingdom against the claims to papal sovereignty that were being made by Pope Innocent VI. Innocent chose Acciaiuoli to negotiate the departure of the Milanese from Bologna in 1360, when he met Petrarch in Milan. Acciaiuoli returned to Naples in 1361 to find the kingdom threatened by marauding mercenary captains. Although he showed considerable personal bravery in surmounting this crisis—at one point he gave himself, his children, and his friends as hostages to a company of Hungarian mercenaries—Acciaiuoli continued to have enemies at court. In 1364, they accused him before Pope Urban V of having taken so many gifts that there was no money to make the usual payments to the papacy. The charges prompted Acciaiuoli to write a long autobiographical letter defending his actions to Angelo Soderini (26 December 1364).

Acciaiuoli died on 8 November 1365. His body was buried in a splendid tomb (attributed to Orcagna) in the Carthusian monastery of San Lorenzo (known today simply as the Certosa) outside Florence, whose construction he had sponsored after first mentioning it in an early autograph testament of 1338.

See also Acciaiuoli Family; Naples

WILLIAM J. CONNELL

Hoshino, Hidetoshi. "Nuovi documenti sulla Compagnia degli Acciaiuoli di Firenze nel Trecento." Annuario dell'Istituto Giapponese di Cultura, 18, 1982-1983.

Léonard, Émile G. "Niccolò Acciaiuoli victime de Boccace." In Mélanges de philologie, d'histoire, et littérature offerts à Henri Hauvette. Paris: Presses Françises, 1934, pp. 139-148.

—. "Acciaiuoli, Niccolò." In Dizionario biografico degli italiani, Vol. 1. Rome: Istituto delPEnciclopedia Italiana, 1960, pp. 87-90.

Palmieri, Matteo. Vita Nicolai Acciaioli, ed. Gino Scaramella. In Rerum italicarum scriptores, 2nd ed., Vol. 13, pt. 2. Bologna: Zanichelli, 1934, (Includes editions of the testaments of 1338 and 1359 and the letter to Angelo Soderini.)

Tanfani, Leopoldo. Niccola Acciaiuoli: Studi storici, fatti principalmente sui documenti dell'Archivio fiorentino. Florence: Le Monnier, 1863.

Ugurgieri della Berardenga, Curzio. Gli Acciaiuoli di Firenze nella luce dei loro tempi, 2 vols. Florence: Olschki, 1962.

Villani, Filippo. Liber de civitatis Florentine famosis civibus, ed. Gustavo Carnillo Galletti. Florence: Mazzoni, 1847, pp. 39-40.

See Banks and Banking; Bookkeeping, Double-Entry

Many biographical details are in dispute regarding the greatest medieval glossator of Roman law. Accursius (also Acursius, Accurxius, or Acurxius; c. 1182-c. 1263) was born at Bagnoio near Montebuoni in the contado (district) of Florence to a family in modest social circumstances, perhaps even of recent peasant origin, that was nevertheless economically secure enough to pay for his legal education at the university in Bologna. Two brothers are mentioned in the sources: Bonus (or Donus, a notary) and Bonajutus. Accursius was also known as A. Fiorentino or A. da Bagnoio, but the sometimes alleged forename Francesco is without historical foundation. In a Digesta gloss he later jestingly explained "that it is an apposite name, because he [Accursius] hurries forward and assists against the darkness of civil law" (quod est honestum nomen, dictum quia accurrit et succurrit contra tenebras iuris civilis).

In Bologna, he studied mainly under the great jurist Azo; Jacobus Balduini was perhaps another of his chief teachers, a supposition that would place some of Accursius's studies in the years after 1213. Tradition places Accursius's promotion and the beginning of his teaching career c. 1215, and more specifically before 1221, when he was identified as doctor legum and a colleague of Azo and Hugolinus in a legal consultation. The dating of this collaboration has recently, however, been questioned, for it could have occurred as late as 1230. Considering Accursius's contemporary eminence among law professors, the number of his distinguished students was small: his own son Francesco; the canonists Vincentius Hispanus and—perhaps—Sinnibaldo Fieschi (later Pope Innocent IV); and probably his younger contemporary Odofredus, also a Romanist. During a teaching career that spanned forty years, Accursius also found time to be a practicing advocate who gave his clients expert legal opinions. There is some dispute regarding whether or when he became a citizen of Bologna; one later historian identifies him in 1252 as an associate of the podestà (podesta), a post held only by noncitizens. But Accursius's attested membership in 1248 in the Societas Tuscorum, a club comprising Bolognese citizens born in Tuscany, more plausibly indicates his possession of this status at least as of that date. His descendants certainly had Bolognese citizenship. Reports of Accursius's hostile rivalry with contemporary colleagues (e.g., Hugolinus and Odofredus) are fictions created later.

Accursius married twice; his first wife bore his eldest son Francesco (1225-1293), his second his remaining sons Cervotto (c. 1240-1287 at latest), Guglielmo (1246-1314 at latest), and Corsino (b, 1254), The disparaging rumors regarding Corsino's paternity were probably due only to the fact that Accursius was about seventy years old at the time. All the sons but Corsino became doctors of law, and two of them (Francesco and Guglielmo) also taught at Bologna. Accursius himself once expressed the opinion that sons of university doctors should receive preference in the filling of vacant chairs, a view that was sometimes put into effect at Bologna after the mid-thirteenth century.

During his career Accursius became quite prosperous. Part of his wealth certainly derived from his professorial stipend and the income from his legal practice. His town house in Bologna was eventually acquired by the city government and later integrated into the Palazzo Comunale. His country villa, "La Riccar dina," was near Budrio; it was the center of an estate so large (271 hectares, or 670 acres) as to permit his sons and grandsons to receive portions of it upon his death. It later became a Franciscan convent. In later times, Accursius's great wealth earned him a bad reputation as a usurer and receiver of bribes from aspiring academic examinees, a charge also made against his son Francesco. Some modern observers remain unconvinced of these charges, citing a lack of trustworthy evidence especially as regards Accursius himself.

Accursius retired from his university post after four decades, that is, c. 1255 or thereafter. One tradition, noting that a ruined house at Bagnolo was subsequently known as the studium Accursii, holds that he returned to the vicinity of his native city. Other historians more plausibly suggest that he retired to his property at Riccardina. Although portions of his masterpiece, the Ordinary Gloss (Glossa ordinaria) on the Corpus iuris civilis, had already been published decades before, it is almost certain that he continued to revise this work throughout his lifetime. As for his other pursuits during these years, one historian (Kantorowicz 1929) has suggested that Accursius now embarked on another monumental, albeit never completed, project: the preparation of a great encyclopedia of both laws, a speculum iuris predating that ultimately written by Guillelmus (William) Durandus. This suggestion rests, however, on an unconvincing reconstruction of the contents of Accursius's library, and at this point must remain an interesting conjecture.

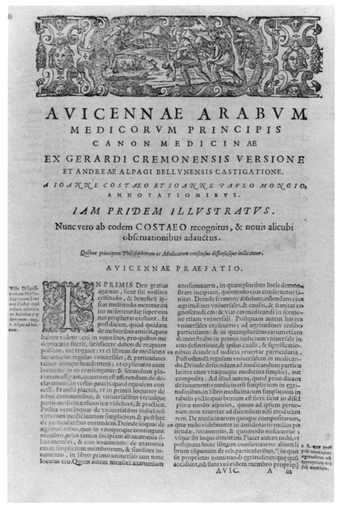

Tomb of Accursius, Bologna. Photograph courtesy of John W. Barker.

Accursius's final years gave rise to another story—that in early 1263 he served in Florence as a resident "judge and assessor" subordinate to the podesta, dying there later that same year during his term in office. This account is inherently implausible, for why would an already rich and very famous man accept such a modest and modestly paid job? A simple confusion of names lies at the bottom of the problem—the Florentine judge and assessor was another jurisconsult, Accursius Reginus (of Reggio Emilia). The date 1263 does, however, provide a terminus ad quern for Accursius's death, for in May of that year a document referred to his son Francesco as condam Domini Accursi. In documents, Accursius was last listed as alive in 1259; a Bolognese chronicle placed his death in 1260, but a document of 1262 listed Cervotto's name in a manner suggesting that his father was still alive. The early fourteenth-century historian Villani wrote that Accursius lived to be seventy-eight. Taken together with reports regarding his birth date, the time frame 1259-1263 for his death is the best available. It is presumed that Accursius died in or near Bologna; he was first interred near San Domenico, but his remains were later moved—at his son Francesco's request—to a monumental sepulcher at the apse ofSan Francesco, where this son was also ultimately interred. The gravestone there is probably from the original grave with the later addition (1293) of Francesco's name: Sepulchrum Accursii Glossatoris legum [et] Francisci eius filii.

Descriptions of Accursius's personal appearance and habits note his tall powerful build, pensive and serious facial expression, affability, modest lifestyle, fine manners, and taste for good but not ostentatious dress. He was a heartfelt Ghibelline, but his posthumous fame was such as to release his entire family, eventually, from the penalties enacted in 1274 by Bologna's triumphant Guelf government for adherents of that defeated party. The amnesty statute of 1306 identified him and Francesco as men "who have conferred such great honor of the city of Bologna, fathers and teachers of all scholars and students of civil law throughout the entire world" (patrum et dominorum omnium scolarium et studentium in iure civili per universum mundum, qui tantum honorem fecerunt civitati Bononie).

Accursius's fame as a scholar rests squarely on his Ordinary Gloss on the constituent parts of Justinian's Corpus iuris emits. His other works are of far less consequence. The Summa authen-tici and Summa feudorum attributed to him by some scholars are considered by others to be the work of, respectively, Johannes Bassianus and Hugolinus. Also, the Tractatus de arbitris attributed to him is a work of his teacher Azo. Accursius edited several extravagant texts to the Librifeudorum, and (at least) eight expert legal opinions (cortsilia) of which he was the author or a coauthor are extant from the period 1230-1258. A letter written to Piero della Vigna is of doubtful authenticity, and various quaestiones are reported secondhand.

See abo Azo; Francesco d'Accorso; Glossa Ordinaria: Roman Law; Innocent IV, Pope

ROBERT C. FIGUEIRA

"Accursius (Ital. Accorso), Franciscus." In Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th ed., 1911, Vol. 1, p. 134.

"Accursius, Franciscus." In New Encyclopedia Britannica, Micropaedia, 15th ed. 1994, Vol. 1, p. 57.

Balon, Joseph. "Accurse." In Grand dictionnaire de droit du Moyen Age (Ius medii aevi, 5). Namur, 1972-, fascicule 1, pp. 143—144.

Clarence Smith, J. A. Medieval Law Teachers and Writers: Civilian and Canonist. Ottawa, 1975. (See pp. 42-44.)

Colliva, Paolo. "Documenti per la biografia di Accursio." In Atti del Convegno Internazionale di Studi Accursiani, ed. Guido Rossi. Milan, 1968, Vol. 2, pp. 381-458.

de Zuleta, Francis. Notice in Law Quarterly Review, 46, 1930, pp. 148-150.

Dilcher, Hermann. "Accursius." In Handwörterbuch zur deutschen Rechtsgeschichte, ed. A. Erler and E. Kaufmann. Berlin, 1971-1998, Vol. 1, pp. 24-25.

Fiorelli, Piero. "Minima de Accursiis." Annali di Storia del Diritto, 2, 1958, pp. 345-359.

—. "Accorso." In Dizionario degli Italiani. Rome, 1960, Vol. 1, pp. 116-121.

Genzmer, Erich. "Zur Lebensgeschichte de Accursius." In Festschrift ftir Leopold Wenger. Munich, 1945, Vol. 2, pp. 223-241.

Kantorowicz, Hermann. "Accursio e la sua biblioteca." Rivista di Storia del Diritto Italiano, 2, 1929, pp. 35-62, 193-212.

Kay, Richard. "Francesco d'Accorso the Unnatural Lawyer." In Dante's Swift and Strong: Essays on Inferno XV. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1978, pp. 39-66, 319-332.

Kisch, Guido. "Accursius' Grabschrift." Atti del Convegno Internazionale di Studi Accursiani, 3, pp. 1239-1244.

—. "Accursius-Studien." Gestalten und Probleme aus Humanismus und Jurisprudenz. Berlin, 1969, pp. 17-97.

Lange, Hermann. Römisches Recht im Mittelalter, Munich, 1997-, Vol. 1, pp. 335-385.

Magnin, E. "Accurse, Francois." In Dictionnaire de droit canonique, ed. R. Naz. Paris, 1935-1965, Vol. 1, pp. 150-151.

Savigny, Friedrich Carl von. Geschichte des romischen Rechts im Mittelalter, 5, 1850, pp. 262-305.

Weimar, Peter. "Accursius." In Lexikon des Mittelalters. Munich and Zurich, 1980-1998, Vol. 1, pp. 75-76.

—. "Accursius." In Juristen: Ein biographisches Lexikon—Von der Antike bis zurn 20. Jahrhundert, ed. Michael Stolleis. Munich, 1995, pp. 18-19.

Adelaide (931-998) was the daughter of Rudolf II of Burgundy. Her intelligence and beauty—in addition to a tenuous Carolingian connection through descent from Welf (Wulf, Wolf)» the brother of Judith, wife of Louis the Pious—made her a desirable marriage prospect. When Rudolf died in 937, Hugh of Provence, who dominated northern Italy and had earlier clashed with Rudolf, obliged Adelaide to marry Lothar, Hugh's son. By 945, Hugh's power declined and Berengar of Ivrea, another warlord, forced him from Italy. Berengar tried to marry Adelaide to his son, Adalbert, when Lothar died in 950. Otto of Saxony rescued and married her (951). This match was successful, and Adelaide was crowned empress with Otto in 962. She accompanied her husband during his six years in Italy (966—972). She was regent for her son, Otto II, and despite some friction when he became emperor, was his viceroy in Italy. When Otto Ill's mother, The-ophano, died, Adelaide assumed the regency for her grandson. She spent her last years in Germany.

See also Otto I

MARTIN ARBAGI

Liudprand (or Liutprand), Bishop of Cremona. Antapodosis and Liber de rebus gestis Ononis. In Die Werke Liudprands von Cremona, ed. J. Becker. Scriptorum Rerum Germanicarum in Usum Scholarum ex Monumentis Germaniae Historicis Separatim Editi, 3rd ed. Hannover and Leipzig: Hahnische Buchhandlung, 1915.

Odilo. Epitaphium Adalheidae imperatricis auctore Odihne, ed. G. Pertz. Monumentis Germaniae Historica, Scriptorum, 4. Hannover and Leipzig: Hahnische Buchhandlung, 1841.

Regino of Priim. Chronicon, ed. F. Kurze. Scriptorum Rerum Germanicarum in Usum Scholarum ex Monumentis Germaniae Historicis Separatim Editi. Hannover and Leipzig: Hahnische Buchhandlung, 1890.

Liudprand of Cremona. Antapodosis, or, Tit-for-Tat and Liber de rebus gestis Ottonis, or, A Chronicle of Otto's Reign. In The Works of Liudprand of Cremona, trans. F. A. Wright. London: Routledge, 1930.

Halphen, Louis, "The Kingdom or Burgundy. In The Cambridge Medieval History, Vol. 3, Germany and the Western Empire, ch. 6. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1922.

Hiestand, Rudolf. Byzanz und das Regnum italicum im 10. Jahrhundert. Zurich: Fretz and Wasmuth, 1964.

Kreutz, Barbara M. Before the Normans: Southern Italy in the Ninth and Tenth Centuries. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1991.

Leyser, Karl. "The Women of the Saxon Aristocracy." In Rule and Conflict in an Early Medieval Society. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1980, pp. 49-73.

Previte-Orton, Charles. "Italy in the Tenth Century." In The Cambridge Medieval History, Vol. 3, Germany and the Western Empire, ch. 7. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1922.

The Adimari were one of the noblest and most powerful of Tuscany's great medieval families. Originally Franks who took over Lombard land around Florence, the family stemmed directly from Count Adimaro (mid-tenth century), son of Marquis Bonifazio and brother of Tedaldo, founder of the Alberti clan. From their castle of Gangalandi and other strongholds, they controlled traffic on the Arno River, and Florence battled them to submission. By 1178, Bernardo Adimari was serving as communal consul in Florence. The Adimari had become leading urban nobles as well, with a group of towers and houses centered on Via Calzaiuoli, near the Baptistery; one tower, Guardamorto, reached a height of 70 meters (230 feet). They were active in commerce and banking, with offices in Genoa by the 1260s and in Treviso somewhat later.

By the thirteenth century, the Adimari were powerful politically, as Ghibelline-hating Guelfs, and members of the family served as podestas (a podestà is a mayor or peacekeeper) in Tuscan towns such as Arezzo, Pistoia, and San Gimignano, as well as captains of the parte Guelfa (Guelf party) in Florence. Their continual feuding brought about their denunciation as magnates under the Ordinances of Justice in 1293.

Branches of the family included the Aldobrandini, Argenti, and Cavicciuli, who, in the later thirteenth century, were usually among the White Guelfs. A rare Black Cavicciuli took over the property of the exiled Florentine poet Dante Alighieri and opposed his return. Dante placed Tegghiaio Aldobrandi among the sodomites (Inferno, 6.79-81, 16.40-42) and, likewise, placed Filippo Argenti, of the "arrogant race," oltracotata schiatta (Paradiso, 17.115), in hell (8.32-63).

Despite their decline in political power, the family remained large and rather wealthy (with thirty-three taxable households in 1378) through the fourteenth century.

See also Florence

JOSEPH P. BYRNE

Brucker, Gene. Florentine Politics and Society, 1343-1378. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1962.

Davidsohn, Robert. Storia di Firenze. Florence: Sansoni, 1956-1968.

Flavius Aëtius (d. 454), sometimes called the "last of the Romans," was born at the end of the fourth century in the Roman province of Lower Moesia on the Danube River. He was the son of the master of soldiers Gaudentius and an Italian noblewoman. He pursued a military career, and in his youth he served as a hostage first to the Visigoths and then to the Huns. Under the western usurper Johannes (423—425) he held the office of overseer of the palace. He was sent to recruit a large army of Huns, but he did not return to Italy with them until after the fall of Johannes, at which time he was able to make his peace with the new emperor, Valentinian III. Aetius then served as master of soldiers, primarily in Gaul, during which time he became involved in a quarrel with another western general, Count Boniface. In 432, Aetius was defeated at Rimini by his rival, who himself was mortally wounded. Aëtius then took refuge with the Huns, and with their aid he soon was restored to power. In 433, he became supreme master of soldiers; the title "patrician" was added in 435.

Aëtius spent most of his remaining years campaigning in Gaul. In spite of the virtual disappearance of the Roman army, he was generally successful in keeping the barbarians out of Italy by masterfully playing one barbarian group off against another. In 451, he used a coalition of Romans, Visigoths, and Franks to defeat the invasion of Attila and the Huns. In 452, however, he inexplicably failed to defend the Alpine passes against Attila's return, and only after the Huns had captured Milan and destroyed Aquileia were they compelled to withdraw.

Aëtius exemplifies the powerful generalissimos who, in the fifth century, truly controlled the western empire. During most of the second quarter of that century, Aëtius was the most powerful Roman of the west, the real "power behind the throne." He held the consulate no fewer than three times, in 432, 437, and 446. Around 440, the senate in Rome honored him with a statue; its inscription is still extant. He was married twice, first to a daughter of the count of the domestics, Carpilio (her name has not survived), and second to Pelagia, the widow of Boniface. In the early 450s, his status was enhanced by the betrothal of his son Gaudentius to Valentinian's daughter, Placidia.

Eventually, however, Aëtius's preeminent position was his own undoing. In 454 Aetius was murdered in the imperial palace by the emperor Valentinian himself: a Roman aristocrat later told the emperor that he "had cut off his left hand with his right."

It may be that Aëtius's efforts delayed, for a time, the eventual fall of the western Roman empire. After his death, the western empire rapidly disintegrated and soon shriveled to an Italian core, which itself fell under barbarian control in 476.

See also Valentinian III

RALPH MATHISEN

Degrassi, Attilio. "L'iscrizione in onore di Aezio e l'Atrium Libertatis." Bollettino della Commissione Archeologica Comunale di Roma, 72, 1946-1948, pp. 33-44.

Lizerand, Georges. Aetius. Paris, 1910.

Moss, J. R. "The Effects of the Policies of Aetius on the History of the Western Empire." Historia, 22, 1973, pp. 711-731.

O'Flynn, J. M. Generalissimos of the Western Roman Empire. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 1983.

Tackholm, Ulf. "Aetius and the Battle on the Catalaunian Fields." Opuscula Romana, 7, 1969, pp. 259-276.

Twvman, Briees L. "Aetius and the Aristocracy." Historia, 19, 1970, pp. 480-503.

Zecchini, Giuseppe. Aezio: L'ultima difesa dell'occidente romano. Ricerche e Documentazione sull'Antichita Classica, 8. Rome: "L'Erma" di Bretschneider, 1983.

Agilulf (d. 616) was king of the Lombards from 590 until his death, following Authari. He had been duke of Turin before his accession and legitimized his position by marrying his predecessor's widow, Theodolinda.

During his reign, Agilulf solidified the Lombard conquest of large portions of northern Italy by making peace with the Franks and establishing a fairly stable boundary with the exarchate of Ravenna. The relative independence of the more southern duchies of Spoleto and Benevento was also confirmed. Thus the Lombard kingdom was established essentially as it was to remain until the eighth century.

Agilulf's court was increasingly influenced by Roman and Catholic forms, and a Roman historian, Secundus of Non (from the Trentino), resided there. He welcomed the Irish Columbanus and granted him land at Bobbio, where a monastery was established.

Agilulf was succeeded by his son Adaloald, whose reign inaugurated a period of dynastic strife that had both national and religious overtones.

See also Authari; Benevento; Lombards; Ravenna; Spoleto

KATHERINE FISCHER DREW

Foulke, William Dudley, trans. Paul the Deacon History of the Lombards. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1974.

Hartmann, L. M. "Italy under the Lombards." In Cambridge Medieval History, Vol. 2. New York: Macmillan, 1913.

Wickham, Chris. Early Medieval Italy. Totowa, N.J.: Barnes and Noble, 1981.

In medieval Italy, as elsewhere in Europe, farming practices were constrained by basic ecological facts that people found extremely hard to overcome. The uncultivated world of forest, marsh, and heath, although often feared as "wild," had to be exploited for all the food and building materials it could provide because the success of agriculture was very uncertain. Medieval farmers, like farmers in all premodern societies, found it difficult to cope with the almost randomly occurring "good years" and "bad years" for crops. Cultivation methods were often too rudimentary to produce much in the way of a surplus, and if any surplus could be accumulated, storage techniques were often inadequate to prevent rotting and insect damage. Climate was the most unpredictable natural element. Abnormally low winter and summer temperatures (as in the cold period between a.d. 600 and 800) could have disastrous effects on even the most carefully tended crops, but comparatively warm times (as between 1000 and 1250) helped farmers to increase yields. Obvious regional differences in climate— as between Lombardy and Apulia—determined what crops could be attempted in the first place; but it is likely that microclimatic peculiarities, which are now becoming better understood as a result of archaeological investigations involving analyses of pollen and other plant remains, helped to define the agricultural character of a given area at a much more local level. Exploiting difficult terrain was also problematic, since it was hard to drain and dig large forested, marshy, or steep areas with hoes, spades, and very simple plows. The labor required was phenomenal; this explains why the vast majority of medieval people had to be agriculturists. Consequently, agricultural life was harsh and remained so between the millennium 400 and 1400, despite the changes in farming practices, technology, and economic organization that were taking place in Italy. (Real improvements in conditions had hardly taken place before the twentieth century.)

Still, agriculture was in many ways more richly diverse in medieval Italy than it had been in Roman times. This can be seen from the very wide variety of crops, many of which had not been cultivated in Italy in the Roman period. Most descriptions of medieval Italian agriculture stress, rightly, that its basis was cereals, vines, and olives, the classics of Mediterranean farming and diet. Cereals were widely grown, the choice of grain depending on the soil quality, terrain, rainfall, and so on. Predominantly, the farmers of the early Middle Ages grew the so called poorer cereals (barley, rye, oats, millet, and sorghum); but olives were also common—in fact, they were present almost everywhere.

Cereals, vines, and olives may have been the most characteristic crops, but many other plants, edible and nonedible, were raised. Of staples, the chestnut was particularly important in hilly regions, especially in the Appennines; it was not a "wild" plant but was carefully cultivated and highly valued. Vegetables and fruits are not mentioned so commonly in the historical sources, but that may be because their presence was taken for granted. Certainly orchards were prized, and they were common near the northern lakes, in Romagna and the Marches. New citrus fruits—lemons, bitter and sweet oranges—were introduced into southern Italy from the east in the later medieval period. Other new exotics, like sugarcane, also appeared at that time. Important plants grown for textiles and dyes included flax, hemp, madder, and woad in the north, and cotton and saffron in the south.

Stock raising has received rather less attention from historians than plant cultivation, but there can be little doubt that it had a crucial place in the medieval Italian economy. Animals provided fertilizer and energy for farming, both of which were in short supply from other sources. The commonest animals raised were pigs, sheep, goats, and cattle, supplemented by horses, asses, and poultry. Fish, too, were sometimes farmed. As with plants, techniques of animal husbandry varied across Italy. How animals were raised also seems to have depended on what products they were required for. According to the archaeologist Gillian Clark, evidence from many central Italian excavations indicates that dead animals were mainly used for meat and leather (primary use); that living animals were exploited for wool, hair, eggs, and milk (secondary use); and that stock-raising techniques varied accordingly (younger animals were intended for meat, older animals for wool and other products). Many farms seem to have kept a motley mixture of animals, but in the later Middle Ages specialized production of beef cattle began to become important in some areas, notably Farfa Abbey and the Arno valley in Tuscany, Apulia, and the lower Po plain. Animals were useful because their pastures were land that was often unsuitable for other purposes, but they could also be extremely labor-intensive when transhumance was involved—that is, when animals were taken on the great annual summer movements from plains to hills and back again. Transhumance was common in the Appennines, although not in the Alps. Apart from this movement, most Italian agriculture was suited to a sedentary settled existence and was organized accordingly.

There were many variations in the organization of agricultural production across Italy. It is likely that most agriculturalists lived on small holdings, in family units, often within the framework of a nucleated village settlement to form, in Pierre Toubert's phrase, a "complete peasant exploitation." These peasant farmers produced food for themselves and their families, and sometimes a surplus that was either sold or given as rent to a powerful local lord. The relationship between peasants and lords took differing forms. Often, it is hard for historians to characterize such a relationship with any precision, because contracts between cultivators and noncultivators were usually not written down in the period before about 1200. Therefore, it is extremely hard to know to what extent the secular or monastic owners of large estates actually determined what was produced there, or if the peasants were given a free hand so long as they produced a surplus with which to pay the owner. Italy, like many other regions in medieval Europe, can be said to have had a "manorial system" (a rough translation of the Italian sistema curtense), particularly between about 800 and 1000. Nowadays, historians emphasize that such estates were organized locally in many different ways and were not self-sufficient as commonly as had previously been thought. This was because the agricultural economy—with the possible exception of some (not all) particulary isolated mountain farms—was never static and was never removed from the wider ecological and economic systems of Italian society.

Toubert proposed a helpful typology of earlier medieval Italian estate structures that has become the standard framework for analyzing the organization of agricultural practice. Toubert suggests a threefold division of widely recognizable types:

Examples of each type have been found by historians all over Italy during most periods. Toubert's discussion is valuable because it provides a reminder that a degree of specialization in production was evident in Italian practice from the early Middle Ages on. This seems to have been particularly true in two contexts: monastic estates, where abbots often demanded cash-crop production of oil and wine and caused some land to be opened up to agriculture for the first time; and farms near towns, where, increasingly in the later period, specialized market garden crops were grown for urban sale.

It is not always easy to imagine, from the surviving texts, what these estates actually looked like on the ground. However, certain general points can be made. The cultivated landscape in most places was a combination of open (terra aperta) and enclosed fields (clausurae), in close proximity to uncultivated land. The proportions at any given time and place are almost impossible to work out. However, one can generalize by saying that in the earlier period there were more open fields, which were sometimes communally owned and worked by the village, whereas from the twelfth century on more enclosed fields appeared, especially around Milan, as more owners fenced off plots from communal use. This development spread to the rest of Lombardy, Liguria, and Tuscany in the thirteenth century and a little later to Lazio and Campania. Most of these changes seem to have taken place veiy slowly, with a consequent gradual change in the appearance of the landscape. Occasionally, more obvious changes took place more rapidly. There was probably more land under cultivation in Italy during the medieval period than at any earlier time, and this was largely a result of a new combination of efforts by the peasants and pressure from the monasteries. Vito Fumagalli has found that the monasteries of Nonantola and Bobbio caused new areas of the lower Po plain to be opened up for agriculture by deforestation and drainage as early as the first half of the ninth century. Their abbots pursued this as a deliberate policy by issuing special libellus contracts to peasants requiring them to undertake clearance as part of their contractual relationship with the community. Terms such as novellae (new plots) and noviculta (newly cultivated) also appear in charters from elsewhere in the Po valley.

The farmers had little in the way of new technology to aid them in transforming the landscape. Most of their basic tools were ancient and did not change for centuries. The most important technological change was the increasingly widespread use of the water mill from about 1000 on. It made the milling of flour much more efficient, as did the later introduction of the windmill to Lombardy around 1300. New irrigation techniques borrowed from the Arabs aided the cultivation of rice and cotton in the south.

The study of medieval Italian agriculture is now entering a new phase with the increasing use of advanced archaeological techniques to analyze site data such as pollen, grain samples, animal bones, and farming implements, allowing a more precise picture of individual agricultural sites and their production in the medieval period. These new techniques are important because only through them can we determine how much of medieval practice was inherited from Rome and how much was true innovation. Perhaps even more exciting is "landscape archaeology." Landscape archaeology uses the field survey—pioneered in central Italy by teams from the British School at Rome—to analyze large areas and observe changes in land use and settlement patterns over a longer span of time than is possible with conventional historical methods. Notable among these surveys are those of south Etruria, the Biferno valley, and Farfa, which have given us more precise data than ever before about what was grown where.

See also Land Tenure and Inheritance; Peasants; Revenues; Transhumance; Viticulture

ROSS BALZARETTI

Andreolli, Bruno, and Massimo Montanari. L'azienda curtense in Italia. Bologna: Cooperativa Universitaria Editrice, 1983.

Barker, Graeme. "The Italian Landscape in the First Millennium A.D.: Some Archaeological Approaches." In The Birth of Europe, ed. Klaus Randborg. Rome: Bretschneider, 1989, pp. 62-73.

Clark, Gillian. "Animals and Animal Products in Medieval Italy: A Discussion of Archaeological and Historical Methodology." Papers of the British School at Rome, 44, 1989, pp. 152-171.

Dean, Trevor, and Christopher J. Wickham, eds. City and Countryside in Late Medieval Italy: Essays Presented to Philip Jones. London: Hambledon, 1990.

Fumagalli, Vito. Terra e societa nell'Italia padana, Vol. 1, Secoli ix e x. Turin: Einaudi, 1976.

—, ed. Le prestazione d'opera nelle campagne italiane del medioevo. Bologna: Cooperativa Universitaria Editrice, 1987.

Herlihy, David. "The History of the Rural Seigneury in Italy, 751-1200." Agricultural History, 33, 1959, pp. 58-71.

Jones, Philip J. "An Italian Estate, 900-1200." Economic History Review, Series 2, 7, 1954, pp. 18-32.

—. "A Tuscan Monastic Lordship in the Later Middle Ages: Camaldoli." Journal of Eccesiastical History, 5, 1954, pp. 168-183.

—. "Medieval Agrarian Society in Its Prime: Italy." In Cambridge Economic History of Europe, 2nd ed., Vol. 1, ed. M. Postan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1966, pp. 340-431.

Luzzatto, Gino. An Economic History of Medieval Italy, trans. Philip Jones. London, 1965.

Mazzaoui, Maureen. The Italian Cotton Industry in the Later Middle Ages, 1100-1600. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981.

Montanari, Massimo. L'alimentazione contadina nell'alto medioevo. Naples: Liguori, 1976.

Toubert, Pierre. "L'ltalie rurale aux viii-ix siècles: Essai de typologie domaniale." Settimane di Studio del Centro Italiano di Studi sullAltro Medioevo, 20. Spoleto, 1973, pp. 95-132. (Reprinted in his Études sur l'Italie médiévale, ix-xiv siècles. London: Variorum, 1976.)

—. "Il sistema curtense: La produzione e lo scambio interno in Italia nei secoli viii, ix, e x." In Storia d'Italia: Annali 6. Turin: Einaudi, 1983, pp. 5-63.

Wickham, Christopher J. Early Medieval Italy. London: Macmillan, 1981.

—. "Pastoralism and Underdevelopment in the Early Middle Ages." Settimane di Studio del Centra Italiano di Studi sull'Alto Medioevo, 31. Spoleto, 1983, pp. 401-451.

Aistulf (d. 756) became king of the Lombards in 749 by overthrowing his brother Ratchis, presumably because Ratchis was not following an expansionist policy aggressively enough. Under Aistulf, the Lombards in 751 occupied Ravenna and moved toward Rome. Pope Stephen II appealed for aid to the Franks, who were indebted to the papacy because it had legitimated the new Carolingian dynasty. In 755, the Franks under Pepin I invaded, defeated Aistulf, and obtained an agreement that the Lombards would cede to the papacy all of the exarchate they had occupied. When Aistulf failed to carry out these terms, Pepin invaded again, in 756, and forced compliance. When Aistulf died there was a brief interregnum; he was then succeeded by Desiderius.

See also Desiderius; Frankish Kingdom; Lombards; Pepin the Short; Ratchis; Ravenna; Stephen II, Pope

KATHERINE FISCHER DREW

Hallenbeck, Jan T. Pavia and Rome: The Lombard Monarchy and the Papacy in the Eighth Century. Philadelphia, Pa.: American Philosophical Society, 1982.

Noble, Thomas F. X. The Republic of Saint Peter: The Birth of the Papal State, 680-825. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1984.

Wickham, Chris. Early Medieval Italy. Totowa, N.J.: Barnes and Noble, 1981.

Alaric (c. 370-410) was one of the Visigoths who were allowed to cross the Danube River into the Roman empire by the emperor Valens in 376. The Visigoths were the first group of barbarians to be allowed into the empire en masse, and their arrival marked the beginning of the "barbarian invasions." In reality, the Visigoths were more a motley conglomeration of ruffians than a discrete ethnic entity. They were augmented by accretions of renegades, deserters, slaves, dispossessed peasants, and other barbarian tribes.

Alaric himself first appears in history in the early 390s as a Visigothic military leader. In 394, he served in Theodosius's campaign against the usurper Eugenius, but then, unhappy about not receiving a sufficient reward, he revolted. Between 395 and 397, he and his Goths devastated Thrace and Greece, sacking several famous cities and on several occasions escaping destruction by the western general Stilicho. In 398 or 399, Alaric was granted the office "master of soldiers of Illyricum." In spite of this honor he invaded Italy in 401 and besieged the emperor Honorius in Milan. In 402, he was defeated at Pollentia and again at Verona by Stilicho, who then allowed him to withdraw from Italy. In 407, Alaric was engaged by Stilicho in a plan to seize Illyricum for the west, but this scheme was frustrated by the revolt of Constantine III in Britain and Gaul (407-411).

After Stilicho was murdered in 408, many of his partisans joined Alaric, who had since moved into the province of Noricum on the northern Italian border. Then, when Honorius refused to pay Alaric for past services, the Visigoths invaded Italy once again in 408 and besieged Rome, having been promised assistance from a group of Visigoths and Huns led by Alaric's relative Athaulf. A long series of negotiations then ensued among Alaric, the senate at Rome, and Honorius, who by then was safely ensconced in Ravenna. The siege of Rome was alternately lifted and renewed several times as Honorius continued to delay, the main sticking point being Honorius's refusal to make Alaric master of soldiers. In 409, Alaric even allowed the senate to name a new emperor, Priscus Attalus, who then granted Alaric his desired rank. Finally, in 410, after being joined by Athaulf and attacked by imperial forces, Alaric returned to Rome, which he captured and sacked beginning on 24 August. As sacks go, this one was rather genteel. It lasted only three days, and the churches, at least, were generally left untouched. The damage was more psychological than material. For the first time in 800 years Rome had fallen. No longer could the city be called Roma invicta ("unconquered Rome").

After leaving Rome, Alaric and his men traveled south, hoping to cross to Sicily. Foiled in this endeavor when the Gothic fleet was wrecked, Alaric turned back north, and on this journey he became ill and died in Bruttium. He was said to have been buried in the bed of the Busento River after the stream had been diverted. His position then was taken by Athaulf, who, two years later, led the Goths into Gaul.

See also Honorius, Emperor; Stilicho; Visigoths

RALPH MATHISEN

Brion, Marcel. Alartc the Goth, trans. Frederick H. Martens. London, 1932.

Matthews, John F. Western Aristocracies and Imperial Court A.D. 364-425. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1975.

Mommsen, Theodor. "Stilicho und Aiarich." Hermes, 38, 1903, pp. 1-15.

Alberic (fl. 1065—1100) was a monk, deacon, and teacher or grammar and rhetoric at the abbey of Monte Cassino under its great abbot Desiderius. Alberic's life offers few fixed dates. He was probably born in southern Italy and was at Monte Cassino (to which he may have come as an adult) by 1065. In 1078— 1079, he successfully defended orthodox eucharistic doctrine against Berengar of Tours at a Roman synod; perhaps during the 1080s he composed a lost work, Contra Heinricum imperatorem de electione romani pontificis. He died before 1105 (when his name appears in two datable Cassinese necrologies) and was buried in Rome.

The chief primary sources for Alberic's life are the Chronicon Casinensis (3.35) and De viris illustribus (21), both by Peter the Deacon, a twelfth-century archivist and historian of Monte Cas-sino. Of Alberic's prose writings listed by Peter, those on music, astronomy, and dialectic are lost, as are De virginitate sancte Marie and his "very many" letters to Peter Damian. His rebuttal ofBerengar, De corpore domini, has recently been identified. Five saints' lives are attributable to Alberic, and a homily and verses on Saint Scholastica (with her brother, Saint Benedict, buried at Monte Cassino); other hymns and rithmi named by Peter the Deacon are not by Alberic. Alberic helped Desiderius compile four books of Dialogi recounting miracles among the monks of Monte Cassino (Chronicon Casinensis, 3.63).

Alberic is best-known, however, for his writings on rhetoric and style, all of which reflect the needs of classroom teaching and an active writing community. The Liber dictaminum et salutationum named by Peter may refer either to one part of the Breviarium de dictamine (preserved in five manuscripts, only one complete), which in its present form combines grammatical and rhetorical material from various sources, or—though this is less likely—to the Flores rhetorici (also called Dictaminum radii, known from four manuscripts). The Liber de barbarismo et soloecismo tropo et schemate draws on numerous texts, including Cassiodorus's massive Expositio psalmorum and some distinctively Cassinese sources, to define and illustrate (chiefly from the Bible) a remarkable total of nearly 130 rhetorical figures. Finally, a work on syllable length bespeaks an interest in prosody, and Alberic may also have been responsible for a Lexicon prosodaicum, a systematic, alphabetized guide to metrical quantities in classical Latin poetry.

Debate about Alberic's importance in the history of medieval rhetoric, especially the beginnings of the an dictaminis, has been handicapped, though seldom inhibited, by the fragmentary publication of his works. Dictamen means artistic composition in general, and both the Flores and the Breviarium concentrate on techniques of rhetorical ornament in prose. The term refers especially to letter-writing, however—an important literary genre throughout the Middle Ages—and these two works, as the first to contain instruction accompanied by sample salutations and model letters, presage the twelfth-century ars dictaminis with its many handbooks devoted to epistolary theory and model letters.

Alberic himself was a precocious student: in a recently discovered letter accompanying his Passio sancti Cesarii that exudes self-confidence and stylistic polish, Alberic declares that he is thirteen years old and has been engaged in liberalibus studiis for six years. Like most of his other hagiographical compositions, this one reworks an existing text (and as such represents a typical school exercise); it uses the cursus (techniques of rhythmic prose) and displays his characteristic exuberant delight in manipulating language.

See also Ars Dictaminis; Monte Cassino, Monastery

CAROL D. LANHAM

Breviarium de dictamine, ed. Ludwig Rockinger. Briersteller und Formelbiicher des Eilften bis Vierzehncen Jalirhunderts, Quellen und Erorterungen zur Bayerischen und Deutschen Geschichte, 9.1. Munich, 1863. (Extracts. Reprint, New York: Ben Franklin, 1961, pp. 29-46.)

Flores rhetorici, ed. Mauro Inguanez and Henry M. Willard. Miscellanea Cassinese, 14. Monte Cassino and Rome: Arti Grafiche Fotomeccaniche Sansaini, 1938.

"Flowers of Rhetoric," trans. Joseph M. Miller. In Readings in Medieval Rhetoric, ed. Joseph M. Miller, Michael H. Prosser, and Thomas W. Benson. Bloomington and London: Indiana University Press, 1973, pp. 131-161.

Lentini, Anselmo. "Alberico di Montecassino, Senior." Dizionario biografico degli Italiani, 1, 1960, pp. 643-645.

Repertorium fontium historiae medii aevi. Rome: Istituto Storico Italiano per il Medio Evo, 1967, Vol. 2, pp. 165-167.

Bloch, Herbert. "Monte Cassino's Teachers and Library in the High Middle Ages." In La scuola nell'Occidente latino dell'alto medioevo. Settimane di Studio del Centro Italiano di Studi sull'Alto Medioevo, 19. Spoleto, 1972, pp. 563-605. (See especially pp. 587-601.)

Gehl, Paul F. "From Monastic Rhetoric to Ars dictarninis: Traditionalism and Innovation in the Schools of Twelfth-Century Italy."American Benedictine Review, 34, 1983, pp. 33-47.

Murphy, James J. Rhetoric in the Middle Ages. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, 1974, pp. 203-211.

Albertanus (c. 1190-1251 or after), an author of legal treatises and addresses, was active in the political and professional life of the commune of Brescia in the first half of the thirteenth century. We know quite a lot about him from his appearances in official records (e.g., as a witness to a treaty or to a legal document) and from what he reveals in his own writings. A causidicus, or legal intermediary, perhaps with judicial powers (the precise function of this role is now unclear), he was regarded highly enough to be called on to serve his commune politically. On at least one occasion he was an aide to his fellow-Brescian Emmanuel de Madiis when the latter went to Genoa as podestà. In 1238, he was entrusted with the captaincy of the fortress of Gavardo, to defend it against the forces of Emperor Frederick II in the struggle of the Lombard League against the imperial campaign in northern Italy. He lost, but only after a vigorous defense against an especially vicious siege.

Albertanus was the author of three Latin didactic treatises and five "sermons"—spoken addresses delivered before his fellow causidici at meetings of their lay confraternity. These works became widely—in fact, explosively—available immediately after their creation and are to be found all across Europe; AJbertanus's works were read and copied until the eve of Reformation. His first (and longest) work is De amore et dilectione Dei et proximi et aliarum rerum et de forma vitae, completed while he was imprisoned at Cremona in 1238. Here he first set out his notion that social transformation is to be achieved through voluntary personal commitment to a "rule," an idea which would permeate all his subsequent writing. A sermon he delivered in Genoa in 1243 provides a prototype for his De doctrina dicendi et tacendi of 1245. Structured according to the rhetorical "circumstances" of classical tradition, this treatise examines the use of spoken discourse, especially among the legal profession, as a means of social empowerment, A third treatise, Liber consolationis et consilii (1246), denounces the threat to order afforded by the urban vendetta—the northern cities of Italy were frequently riven by lobbyists, and street fights between politically partisan groups were far from unknown. In this work, he sees social change as to be achieved through personal moral development. His final works comprise four more sermons, delivered to his legal confraternity in Brescia in or about 1250. In these short sermons, Albertanus develops and reiterates themes of his major works, and they may be seen as reflecting the maturity of his thought. The last sermon, with its topic of fear of the Lord (and perhaps also its lack of clear structure), suggests that these sermons were his swan song. There is no reason to believe that he wrote anything after them, and further attributions of authorship are undoubtedly false.

Albertano drew on familiar sources for his works, among them Seneca, Cicero, Justinian, Cato, Godfrey of Winchester, and the Bible. But he appears also to be the first writer to make use of the work of the Spanish convert from Judaism, Peter Alfonsi, and may well be the first scholar to have assembled ail twelve books of Cassiodorus's Variae. In this sense we can regard Albertanus as a precursor of the Renaissance book collector. The focus and synthesis of his writing, however, make it wrong to dismiss him as a mere compiler. His remedies for the social problems he met with professionally mark him as an early and insightful social theorist. His views on the consensual adoption of a secular rule (propositum) as a way of life and its potential as an engine of social change make him unique for the period. That he wrote as a layman is also remarkable. His beliefs about the role of the legal profession as a body with responsibility for social stability and development reveal an early understanding of the significance of the rise of an urban professional class. His sermons are among the earliest evidence we have of lay preaching and oratory.

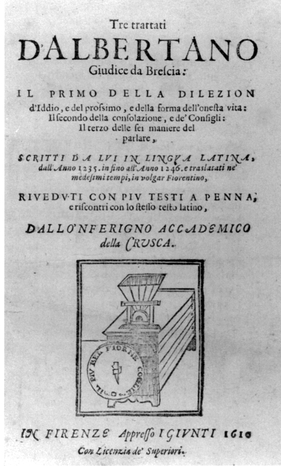

Tre trattati. Florence: Giunti, 1610. Reproduced from original held by Department of Special Collections of the University Libraries of Notre Dame.

More than 320 surviving Latin manuscripts, across Europe, indicate that Albertanus was one of the most widely read authors in the latter medieval period. De doctrina in particular is well represented in manuscript, and it also went through at least thirty-five printed editions by 1500. Among the subsequent writers who knew and utilized these works are Brunetto Latini, Chaucer, John Gower, the author of the Fiore di virtù, Christine de Pizan, and (arguably) Dante. Except for his sermons, Albertanus's work was translated into every major western European language, though sometimes at quite a distance from the original context. More than 130 manuscripts and numerous early printed editions are known of vernacular versions of his treatises; these include English, German, Italian, French, Catalan, Castilian, Czech, and Dutch versions. More research on his influence is needed.

Powell (1992) supplies a recent and authoritative discussion of Albertanus and his works and provides a starting point for contemporary scholars working in English. Some discussion, especially of vernacular versions, is added by Angus Graham (1996), who extends Powell's bibliography. Both supply further reading. Further literature in English is concerned largely with Chaucer's use of Albertanus. Details of Latin manuscripts are given by Navone (1994, 1998), though she lists only 243, and supplemented by Graham (2000a,b). The currently published Latin editions do not reflect the best critical edition, but adequate ones are provided by Sundby (1884, De doctrina, app., 475-509), Romino (1980), Fe d'Ostiani (1874), Ferrari (1955), and more recently by Navone. Ahlquist offers a welcome fresh edition of the four Brescian sermons (with English translation); and Marx has translated, from Sundby, a portion of the Liber consolationis (in Blamires et al. 1992, 237-242). All but two of the published vernacular versions are cited by Graham (1996), and there are further discussions and vernacular manuscript listings in Graham (2000a,b).

See also Brescia

ANGUS GRAHAM

Ahlquist, Gregory W. "The Four Sermons of Albertanus of Brescia: An Edition." M.A. thesis, Syracuse University, 1997.

Blamires, Alcuin, Karen Pratt, and C. W. Marx. Woman Defamed and Woman Defended: An Anthology of Medieval Texts. Oxford: Clarendon, 1992.

Fe d'Ostiani, Luigi F. Sermone inedito di Albertano, giudice di Brescia. Brescia: Pavoni, 1874.

Ferrari, Marta. Sermones quattuor: Edizione curata sui codici bresciani. Lonato: Fondazione Ugo da Como, 1955.

Graham, Angus. "Who Read Aibertanus? Insights from the Manuscript Transmission." In Albertano da Brescia: Alle origini del razionalismo economico, dell'umanesimo civile, delta grande Europa, ed. Franco Spinelli. Brescia: Grafb, 1996, pp. 69-82.

—. "Aibertanus of Brescia: A Preliminary Census of Vernacular Manuscripts." Studi Medievali, 41, 2000a, pp. 891-924,

—. "Aibertanus of Brescia: A Supplementary Census of Latin Manuscripts." Studi Medievali, 41, 2000b, pp. 429-445.

—. "The Anonymity of Albertano: A Case Study from the French "Journal of the Early Book Society, 3, 2000, pp. 198-203.

Navone, Paola. "La Doctrina loquendi et tacendi di Albertano da Brescia: Censimento dei manoscritti." Studi Medievali, 35, 1994, pp. 895-930.

—. Liber de doctrina dicendi et tacendi: La parola del cittadino nell'Italia del Duecento / Albertano da Brescia. Per Verba, Testi Mediolatini con Traduzioni, 11. Tavarnuzze: SISMEL, 1998.

Powell, James M. Albertanus of Brescia: The Pursuit of Happiness in the Early Thirteenth Century. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992.

Romino, Sharon Hiltz. "De amore et dilectione Dei et proximi et aliarum rerum et de forma vitae: An Edition." Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, 1980.

Spinelli, Franco, ed. Albertano da Brescia: Alle origini del razionalismo economico, dell'umanesimo civile, delta grande Europa. Brescia: Grafo, 1996.

Sundby, [Johannes] Thor. Albertani Brixiensis Liber Consolationis et Consilii. London: Chaucer Society and N. Trübner, 1873.

—. Della vita e delle opere di Brunetto Latini, 2nd ed. Florence: Le Monnier, 1884.

Albertino (1261-1329), the greatest Latin poet of his age, was born in Padua of lowly parentage. Orphaned at a young age, he had the responsibility of caring for three younger siblings—two brothers and a sister. (One of the brothers would eventually become the abbot of Santa Giustina, the great Benedictine monastery of Padua.) Early in his life, Albertino earned money by copying books for students at the university; later he became a notary and the son-in-law of the powerful Guglielmo Lemici, a very successful Paduan usurer. With the backing of the Lemici clan and his own natural abilities, he played a prominent role in Paduan public life, at home and abroad, in peace and war, from around 1310 to his final exile in 1325, when the Carrara family finally broke the influence of the Lemici. He died in exile in Chioggia four years later.

But it was not Albertino's successes as orator, statesman, warrior, or diplomat of Padua that make his name illustrious today. It is, rather, his remarkable achievements as a man of letters in the context of a late medieval Italian commune. Even before his emergence as a figure in Paduan political life, Albertino had become a member of a small group of scholars gathered around Lovato de' Lovati, an older Paduan judge. These men studied the Latin poets as an avocation. The existence of Carolingian manuscripts at the Capitular Library in Verona, and in the Benedictine abbey of Pomposa near Ravenna, made possible this learned diversion of the cenacolo padovano ("Paduan circle"). The members of the cenacolo were already familiar with the traditional set of Latin poets, established earlier in the thirteenth century—Virgil, Horace, Ovid, Lucan, and Statius—and Lovato was the first to take the next logical step, composing original Latin poetry himself. Indeed, Petrarch recalled his achievement.

Albertino, following in Lovato's wake, composed poems that helped to rehabilitate some forms of Latin poetry. One example is his defense of such poetry against the strictures of a Dominican, Fra Giovannino. Another is his birthday elegy, in which he reviews his life and the highlights of his career, including his laureation. This may have been the first work since antiquity in which an author focused on his own day of birth for reflection and celebration.

In the 1320s, Albertino went to Siena in his capacity as a diplomat and on the way, near Florence, fell ill. The literary result of this illness was his poem Somnium ("A Dream"), recounting his concept of the afterworld, with particular attention to the nether regions. (Dante's Inferno was already in circulation at this time.)

Albertino also left us a bountiful harvest of Latin prose works, especially contemporary histories of Italy—De gestis Henrici VII Cesaris (The Deeds of the Emperor Henry VII) and De gestis italicorum post Henricum VII Cesarem (Italian Events after the Death of Emperor Henry VII). However, for all his learning and experience, his histories were no match for his poetry, or for the historical text that was at the root of Padua's self-understanding: Ro landino's Chronicles of the Trevisan March.

Albertino also studied the tragedies of Seneca with Lovato and composed introductions to the plays, as well as an explanation of tragic meters for the younger Marsilius of Padua, the author of Defensor pads. In 1315, in imitation of Seneca and in connection with local history, Albertino wrote his finest and most lasting work, Ecerinis (The Tragedy of Ecerinus), about the tyrant Ezzelino III da Romano (1194-1259), the ruler of Verona. Like some of his contemporaries, Albertino saw an analogy between Ezzelino and the current lord of Verona, Cangrande della Scala. Albertino was familiar with the details of Ezzelino's career from Rolandino's Chronicles, which stressed the heroic, united, Catholic character of Paduan resistance. This was the story Albertino found ready to hand as he attempted to awaken his fellow citizens to the danger of renewed aggression by the Veronese. He was inspired to cast this tale in the form of a Senecan tragedy, Thyestes, and thus wrote the first tragedy since antiquity. It was for Ecerinis that Albertino was crowned with laurels, just as Rolandino had been crowned for the Chronicles. However, Albertino failed in his goal of awakening Padua, and Cangrande conquered the city in 1328. Because of his staunch political opposition to Cangrande, Albertino went into exile; he died at Chioggia on 31 May 1329.

See also Ezzelino III da Romano; Lovato dei Lovati; Padua

JOSEPH R. BERRIGAN

Albettino Mussato. Thesaurus antiquitatum et historiarum italiae, ed, Graevius. Leyden, 1722, Vol. 6(2). (Poems.)

—. Rerum italicarum scriptores, ed. L. A. Muratori. Milan, 1727, Vol. 10. (Histories.)

—. Ecerinide, ed. L. Padrin. Bologna, 1900.

—. Mussato's "Ecerinis" and Loschi's "Achilles," trans. Joseph R. Berrigan. Munich: Wilhelm Fink, 1975.

Berrigan, Joseph R. "The Ecerinis: A Prehumanist View of Tyranny." Delta Epsilon Sigma Bulletin, 12, 1967, pp. 71-86.

—. "Early Neo-Latin Tragedy in Italy." In Acta Conventus Neo-Latini Lovaniensis. Leuven: Leuven University Press, 1973, pp. 85-93.

—. "A Tale of Two Cities: Verona and Padua in the Late Middle Ages." In Art and Politics in Late Medieval and Early Renaissance Italy, 1250-1500, ed. Charles M. Rosenberg. Notre Dame, Ind.: University of Notre Dame Press, 1990, pp. 67-80.

Billanovich, Giuseppe. I primi umanisti e le tradizioni dei classici latini, Fribourg: Edizioni Universitarie, 1953.

Billanovich, Guido. " Veterum vestigia vatum nei carmi dei preumanisti padovani." Italia Medioevale e Umanistica, 1, 1958, pp. 155-243.

Cosenza, Mario. Biographical and Bibliographical Dictionary of Italian Humanists. Boston, Mass., 1962, Vol. 3, pp. 2396-2398; Vol. 5, pp. 1223-1224.

Dazzi, Manlio Torquato. Il Mussato preumanista (1261-1329): L'ambiente e l'opera. Vicenza: Neri Pozza, 1964.

Hyde, J. K. Padua in the Age of Dante. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1966.

Martellotti, Guido. "Mussato, Albertino." In Enciclopedia Dantesca. Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 1984, Vol. 3, pp. 1066-1068.

Raimondi, Ezio. "L'Ecerinis di Albertino Mussato." In Studi Ezzeliniani, Fasc. 45-47 of Studi storici. Rome: Istituto Storico Italiano per il Medio Evo, 1963, pp. 189-203.

Weiss, Roberto. The Dawn of Humanism in Italy. London: Lewis, 1947.

Albertus Magnus or Albert the Great of Ratisbon (c. 1193 or 1206-1280) has emerged as one of the great encyclopedist theologians of the late Middle Ages. He entered the Dominican order at Padua in 1223; moved north to teach at the schools of Hildesheim, Cologne, and Ratisbon and then moved to Paris; but in 1248 returned to Cologne, where he organized the Studium General. In 1260, he was appointed bishop of Ratisbon; however, he resigned so that he could concentrate on his literary efforts. H is most distinguished pupil was Thomas Aquinas, whose doctrines he later defended at Paris in 1277.

As a cleric, Albertus was interested in documenting the world around him according to the sanctity of tradition, but he departed from most of his predecessors and contemporaries by actually trying to test some of the legends he recorded in his vast works. His approach to the science of his time represented a major shift from the earlier tradition, which had been based entirely on authority. For example, he tested the story that ostriches like to eat iron by attempting to feed them some nails. To his surprise, the ostriches refused the iron, though they would, he testifies, eat small stones.

The works of Albertus are considered somewhat disorganized and are full of digressions, but they are very comprehensive: in scope, Albertus is exceeded only by Aquinas. Albertus's largest work (although incomplete) is the Summa theologiae. His other works include Commentary on the Sentences of Peter Lombard and Summa de creaturis.

In general, Albertus often avoided the fantastic, preferring direct observation and straightforward commentary on nature; for example, he describes how an herb or a fruit might affect the body, mind, or spirit rather than relating traditional allegories about it. His Book of Secrets of the Virtues of Herbs, Stones, and Certain Beasts, as its title suggests, has more to do with the benefits of herbs and stones and their therapeutic or culinary uses than with their symbolic value for moralizers. His comments are linked to the four humors, which medieval medicine inherited from Hippocrates, the chief physician of the ancient world. In his book On Falcons, Dogs, and Horses, Albertus is clearly interested in the hunt.

As a whole, Albertus's methodology, as expounded in Meta-physicorum, is based on a breakdown of knowledge into the medieval "trivium" and "quadrivium," numbers in themselves replete with symbolism. The trivium comprised the superior areas of learning (i.e., the three divine philosophical and theological subjects); the quadrivium pertained to more practical knowledge, such as music and geometry. Learned persons—in actuality, only the priesthood and the nobility—were those trained in both classes of information.

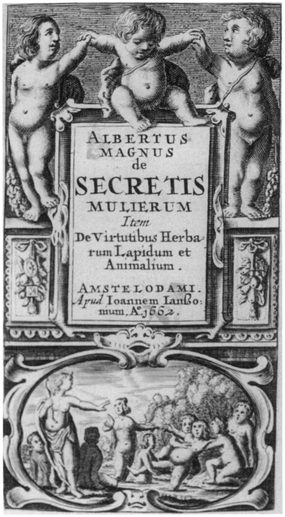

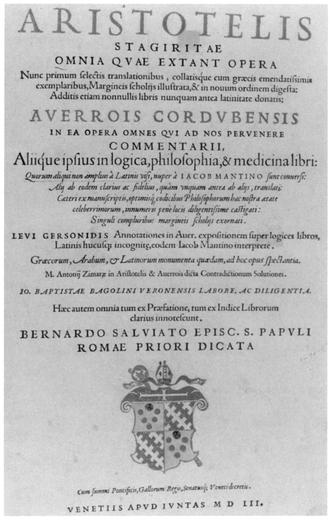

Albertus Magnus, De secretis mulierum; item De virtutibus herbarum, lapidum, et animalium. Amsterdam: Apud Ioannem Ianssonium, 1662. Reproduced from original held by Department of Special Collections of the University Libraries of Notre Dame.

Albertus also had significant influence on artistic taste, through his commentaries on the feminine figure of Mary in De laudibus beatae Mariae Virginis (In Praise of the Blessed Virgin Mary) and Mariale, sive questiones super evangelium: De eorporali puchritudine Mariae (Questions Concerning the Gospel: On the Corporeal Beauty of Mary). Albertus also wrote about the sacramental altar and about what constitutes a reliquary and a sacred site.

See also Thomas Aquinas, Saint

DARRELL D. DAVISSON

Albertus Magnus. Opera omnia, ex editione lugdunensi religiose castigata, et pro auctoritatibus ad fidem vulgatae versionis accuratiorumque patrologiae textuum revocata, auctaque B. AJberti vita ac bibliographia operum a P. P. Quétif et Echard exaratis, etiam revisa et locupletata, cura ac labore Augusti Borgnet. Parisiis, apud Ludovicum Vivès, 1890-1895.

—. Opera omnia ad fidem codicum manuscriptorum edenda /apparatu critico, notis, prolegornenis, indicibus instruenda curavit Institutum Alberti Magni Coloniense, Bernhardo Geyer praeside. Monasterii Westfalorum: In aedibus Aschendorff, 1951- .

—. De la virtu de le her be, animali, et pietre preciose; e di molte maravigliose cose del mondo: E secreti delle done e degli huomini dal medesimo authore composti. Venice, n.p., n.d. (1537).

—. De vegetabilibus libri VII: Historiae naturalis, pars XVIII, ed. Ernesto Meyero. Frankfurt: Minerva GMBH, 1982.

—. De vertus admirables des herbes et des pierres. Paris: GLM, n.d. (1957).

—. Libellus de natura animalium, A Fifteenth Century Bestiary, intro. J. I. Davis. London: Dawson's of Pall Mall, 1958. (Facsimile of 1508 edition.)

—. Le proprietà degli animali, ed. Giorgio Celli. Genoa: Costa and Nolan, 1983.

Albertus Magnus. Art and Sport of Falconry. Chicago, Ill.: Argonaut, 1969.

—. Book of Minerals, trans. Dorothy Wyckoff. Oxford: Clarendon, 1967.

—. The Book of Secrets ofAlbertus Magnus of the Virtues of Herbs, Stones, and Certain Beasts; also A Book of the Marvels of the World, ed. Michael R. Best and Frank H. Brightman. Oxford: Clarendon, 1973.

—. De secretis mulierum; or, The Mysteries of Human Generation Fully Revealed. Written in Latin . . . Faithfully rendered into Engl[t]sh, with explanatory notes, and approved by, the late John Quincy. . . . London: E. Curll, 1725.

—. Man and the Beasts (De animalibus, Books 22-26), trans. James J. Scanlan. Binghamton, N.Y.: Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies, 1987.

—. The Paradise of the Soule. Menston, Yorkshire: Scolar, 1972. (1617).

—. Women's Secrets: A Translation of Pseudo-Albertus Magnus' De secretis mulierum, trans. Helen Rodnite Lemay. Saratoga Springs: State University of New York Press, 1992.

Albertus Magnus and Thomas. Selected Writings, trans, and ed. Simon Tugwell. New York: Paulist, 1988.

Albertus Magnus and the Sciences: Commemorative Essays 1980, ed. James A. Weisheipl. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 1980.

Cross, F. L. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. London, New York and Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1963.

Esposizione e documentazione storica del culto del B. Alberto Magno. Rome, 1930-1931.

Weiss, M. Reliquiengeschichte Alberts des Grossen. Munich, 1930.

Zambelli, Paola. The "Speculum Astronomiae" and Its Enigma: Astrology, Theology, and Science in Albertus Magnus and His Contemporaries. Dordrecht and Boston: KJuwer Academic, 1992.

The Albizzi represented the most conservative element within the merchant aristocracy of republican Florence. A long-established family who were first represented in the signoria in 1283, they attained their greatest commercial and political prominence in the second half of the fourteenth century. By 1350, the Albizzi had emerged as the leaders of a political faction which sought to dominate the parte Guelfa (Guelf party) and the Florentine government by restricting the major offices of both to members of the older families. Opposed to the Albizzi was a faction led by the Ricci that favored the inclusion in politics of new men, those recently risen to wealth and membership in the major guilds.

The rivalry between the Albizzi and the Ricci was regarded by the Florentines as such a threat to the republic that in 1366 both families were banned from holding office for ten years. In 1378, Piero degli Albizzi, whose wealth and political alliances had made him the dominant political figure, was dealt a severe blow by the reform-minded balia created in the wake of the ciompi (working-class) uprising. Piero and his male descendants were declared magnates subject to the political liabilities imposed on the nobility by the Ordinances of Justice, and he was exiled from Florence.

The Albizzi again became the leaders of an oligarchical faction in Florence in the 1380s, and once again their ambition threatened the stability of the republic as they and their new opponents, the Medici, sought to gain control of the machinery of government.

See also Ciompi; Florence

E. HOWARD SHEALY

Brucker, Gene A. Florentine Politics and Society, 1343-1378. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1962.

—. The Civic World of Early Renaissance Florence. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1977.

Najemy, John M. Corporatism and Consensus in Florentine Electoral Politics, 1280-1400. Chapei Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1982.

Velluti, Donato. La cronica domestica di Messer Donato Velluti. Florence: Sansoni, 1914.

The semilegendary king Alboin (d. 572) led the Lombards over the eastern Alps into Italy in 568. He had become king some years before, succeeding his father, Audoin, who was not a member of the old Lething dynasty.

Alboin's career before the descent into Italy is known primarily from old sagas. The Lombards, in league with the Avars, made war on the Gepids (who were living in the central Danube region). The Gepids were defeated, and their king, Cunimund, was killed by Alboin, who then took Cunimund's daughter Rosamund as his captive and wife. It is said that after the invasion of Italy, Rosamund conspired to have Alboin murdered in his bed because he had forced her to drink from a cup made from her father's skull. In any event, Alboin was assassinated in 572.

The invaders that Alboin took into Italy included not only Lombards but also a number of other Germans, including a large group of Saxons. The incursion seems to have taken the Byzantines by surprise. Cividale (Friuli) fell first and became the center of a first Lombard duchy (a frontier march). A number of fare (kin groups) were left to organize the march; the remainder followed Alboin into the Po Valley, where Milan and Pavia (the latter only after a long siege) were occupied and became the center of the slowly emerging Lombard kingdom. Alboin was followed as king by Cleph.

See also Byzantine Empire; Lombards; Milan; Pavia

KATHERINE FISCHER DREW

Foulke, William Dudley. Paul the Deacon: History of the Lombards. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1974.

Wickham, Chris. Early Medieval Italy: Central Power and Local Society 400-1000. Totowa, N.J.: Barnes and Noble, 1981.

Cardinal Gil Alvarez Cabrillo (Carillo, Carrillo) de Albornoz (1302 or 1303-1367) was a soldier as well as a churchman. Albornoz's campaigns restored central Italy to the papacy in the 1350s and 1360s, after decades of control by local despots. This made possible the return of the papal court from Avignon to Rome in 1377, ending the Avignonese papacy.

Born to an aristocratic Castilian family, Albornoz was marked early for an ecclesiastical career. After studying canon law at Toulouse, he became chaplain and counselor to King Alfonso XI. In 1338, he succeeded his uncle as archbishop of Toledo. Over the next decade Albornoz took a leading role in the wars of reconquest, gaining a considerable reputation not only as a soldier but as a diplomat.

Albornoz's relations with King Alphonso's successor, Pedro I (the Cruel), were strained. Fearing disgrace, Albornoz fled to the papal court at Avignon in 1350. By December of that year, he had renounced the see of Toledo and been made a cardinal. In 1352, Pope Innocent VI named him papal delegate and vicar-general to the papal states and to central and northern Italy. His mission was to regain control of these areas from the petty lords who had seized them after the popes left Italy for Avignon.

Albornoz fought two long campaigns in Italy. The first, lasting from 1353 to 1357, secured the papal states, the Marches, and Romagna, including the city of Bologna. The second, fought between 1358 and 1364, attempted to free papal territories from the influence of the Visconti and the Ghibellines of the north by extending papal power into Emilia and the southern reaches of the Po valley.

In 1357, Albornoz promulgated a set of laws for the lands he had conquered that was later known as the Constitutiones aegidianae. This became the basic legal code of the papa! states and was not superseded until the Napoleonic era. Constitutiones attempted to regularize earlier laws of the region while reversing legislation that Albornoz considered prejudicial to ecclesiastical liberties. It also balanced strong papal government with a certain autonomy for towns, since Albornoz was concerned to avoid alienating these important allies against the troublesome nobility. Generally, Albornoz championed communal rights and the authority of communal assemblies against the privileges of the nobles.