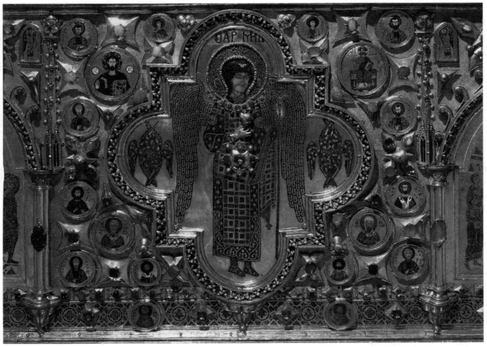

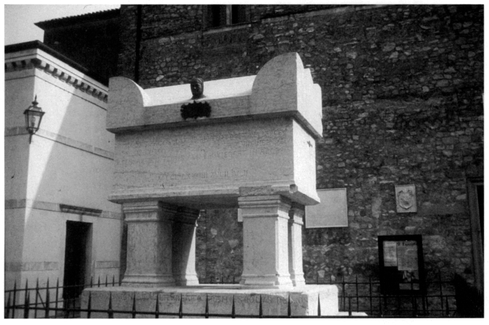

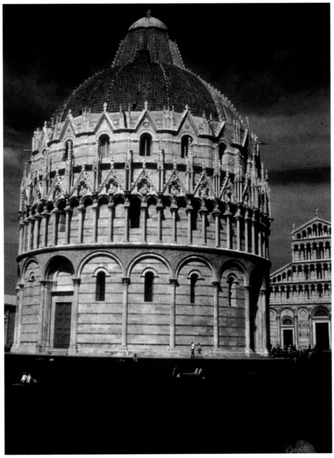

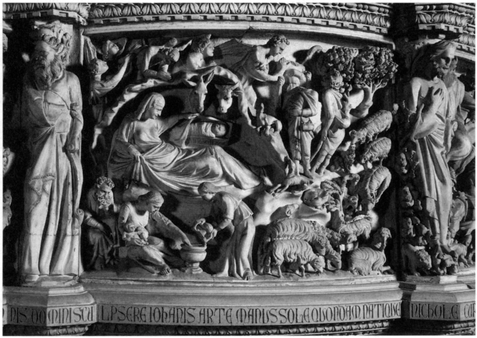

Tomb of Lovato dei Lovati, Padua. Photograph courtesy of Christopher Kleinhenz.

The Florentine painter and illuminator Pacino di Bonaguida (fl. before 1303-c. 1330s) became a leading exponent of what Offner (1923, 1987) described as a "miniaturist tendency" in Florentine painting of the early Trecento. This tendency was prevalent in small-scale panel painting rather than monumental mural art and is characterized by a spirited approach to narrative, keenly observed anecdotal detail, and a shift toward decorative abstraction. To judge from the number of works attributable to Pacino, he commanded a successful workshop, which by 1330 appears to have been the busiest and the most significant center for the execution of manuscript illumination in the city, especially for copies of the works of Dante Alighieri. Pacino's only surviving signed painting is the San Firenze Polyptych (c. 1315-1330; Florence, Accademia), which has been crucial in establishing his artistic personality as well as for building up the not inconsiderable corpus of work linked to him or his bottega. Pacino is first mentioned in 1303 in connection with the painter Tambo di Serraglio, with whom he dissolved a partnership established in the preceding year; he is documented for the last time c. 1330, when he enrolled in a Florentine guild, the Arte dei Medici e Speziali.

Among Pacino's earliest works is thought to be the Tree of Life (c. 1302-1315; Florence, Accademia), originally from the Convent at Monticelli and closely based on Saint Bonaventure's text Lignum vitae. While the solemn air of the crisply defined crucified Christ owes something to the artistic traditions of the Duecento, the episodes in the forty-eight roundels exhibit lucid narrative designs that suggest some awareness of the contemporary art of Giotto. Change is evident in Pacino's later work, however, as the style of the San Firenze Polyptych, which comprises a central Crucifixion with flanking saints, testifies. This altarpiece combines a Giottesque naturalism, conveyed in the convincing plasticity of the forms, with a sense of grace and elegance, especially in the poses and suggested movement of the figures, which are close in temperament to the art of the Saint Cecilia Master.

See also Florence; Giotto di Bondone; Saint Cecilia Master

FLAVIO BOGGI

Boskovits, Miklós. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century—The Painters of the Miniaturist Tendency. Florence: Giunti Barbèra with Istituto di Storia dell'Arte of the University of Florence, 1984.

Frosinini, Valeria. "I corali del Museo Civico di Montepulciano provenienti dalla chiesa fiórentina di Santo Stefano al Ponte." Rivista di Storia delta Miniatura, 5, 2000, pp. 81-95.

Lazzi, Giovanna. "Ancora sulla bottega di Pacino: Un 'messale' miniato della Biblioteca Nazionale di Firenze." Antichità Viva, 33(4), 1994, pp. 5-8.

Offner, Richard. "Pacino di Bonaguida: A Contemporary of Giotto." Art in America, 11, 1923, pp. 3-27.

—. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century, Sec. 3(2), Elder Contemporaries of Bernardo Daddi, new ed. Florence: Giunti Barbèra with Istituto di Storia dell'Arte of the University of Florence, 1987. (New edition with additional material, notes, and bibliography by Miklos Boskovits.)

Offner, Richard, and Klara Steinweg. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting, Sec. 3(2), The Fourteenth Century. New York: College of Fine Arts, New York University, 1930. (Distributed by Augustin.)

Padua (Latin Patavium, Paduensis, Padua; Italian Padova) is a city of the Veneto, situated about 22 miles (35 kilometers) west of Venice on the floodplain between the Bacchiglione and Brenta rivers. The Roman historian Livy, a native of nearby Abano, maintained that Padua was founded by the Trojan hero Antenor. On the basis of the legend, thirteenth-century Paduan chroniclers attributed Trojan ancestry to the local nobility and claimed for their city a preeminence comparable to that of Rome. In 1284, in a gesture of civic pride, the Paduan commune erected in the Piazza Antenore a sarcophagus containing the alleged relics of Antenor. The city, however, was probably founded by the Veneti, a tribe of uncertain origins who settled in the region in the tenth century B.C. Padua was an ally of Rome by the third century B.C. and a subject city from the early second century onward. It obtained Latin rights in 89 B.C. and full Roman citizenship in 49 B.C.

Tomb of Lovato dei Lovati, Padua. Photograph courtesy of Christopher Kleinhenz.

Ancient Padua flourished as a trade nexus and a center for the manufacture of woolen textiles. By the time of Augustus it ranked second only to Rome in wealth, but from the fourth century after Christ it experienced a decline, accelerated by the Germanic migrations. It was sacked by the Huns under Attila in 452, and it passed to the Ostrogoths in 476. The city was captured by Justinian's armies during the Gothic wars and remained under Byzantine control until the Lombards occupied the region at the end of the sixth century. An unsuccessful rising against the Lombard king Agilulf in 601 resulted in a long siege and the virtual destruction of the city. Until the ninth century, the center of municipal activity in the Padovano (the province of Padua) moved to Monselice, about 12 miles (20 kilometers) to the southwest. As part of the Lombard duchy of Friuli, the region passed to the Franks in 774, when Charlemagne annexed the kingdom of Italy.

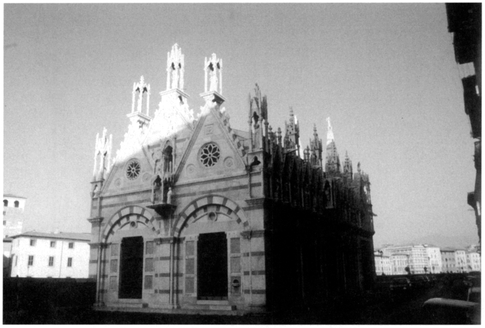

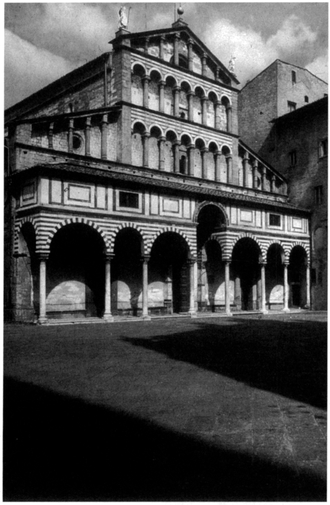

Duomo and baptistery, Padua. Photograph courtesy of Christopher Kleinhenz.

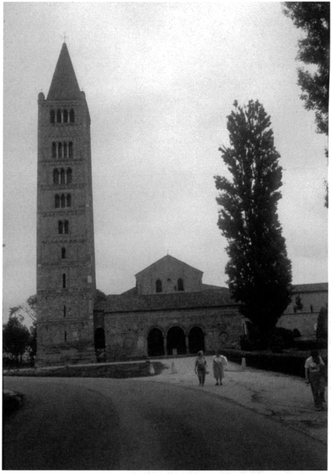

During this period, a measure of continuity was provided by the church. According to legend, the first bishop of Padua was Prosdocimus, reputedly a disciple of the apostle Peter, and an early cult of Saint Prosdocimus is attested to by a sixth-century Italo-Byzantine shrine preserved under the present basilica of Santa Giustina. The first historical evidence of a bishop in Padua dates from the mid-fourth century. The see survived the Germanic migrations, but the bishops of the seventh century suffered exile and a loss of territorial jurisdiction through their adherence to the Nestorian doctrine of the "Three Chapters," which had been condemned as heretical by Rome. To this period belongs the foundation of the Benedictine monastery of Santa Giustina. Generously endowed with rural estates and tithes, the monastery became the richest religious corporation in medieval Padua. The Carolingians restored some of Padua's former importance as an ecclesiastical and administrative center. The ninth century saw the construction of the church of Santa Sophia, a cathedral, and new walls enclosing the Roman city. Little survives of the original cathedral, which was renovated in the twelfth century and entirely rebuilt in the Renaissance after designs by Michelangelo. Santa Sophia, the oldest extant church in Padua, was reconstructed in the twelfth century in a Lombard Romanesque style but retains its original apse, modeled on the Byzantine churches of the Ravenna exarchate. With the disintegration of the Carolingian empire, accumulated feudal and jurisdictional privileges, which after 897 included comital powers, left the bishop virtually the sole public authority in the city and the immediate district. In the tenth century, Bishop Peter (r. 897-904) defended Padua against the Hungarians; early in the eleventh century, Ursus (r. 992-1015) sponsored an extensive reconstruction of the city. Later, Uldericus (r. 1064-1083), a partisan of Pope Gregory VII in a region that was generally pro-imperial, played a role in the investiture controversy as an intermediary between the pope and Emperor Henry IV.

For administrative purposes, the Carolingians divided the Lombard duchy of Friuli into four counties, one of which was centered at Padua. At the end of the tenth century, the Ottonian emperors renewed the jurisdiction of the counts of Padua, with the exception of the city, where the bishop retained comital privileges. But within a century, the Germanic custom of partible inheritance had caused the title of count and the powers associated with it to become dispersed among several branches of the Conti family, some of which merged into the urban citizen body. Other lines, such as the Da Carturo, the Schinelli, and the Maltraversi, remained powerful feudal landowners, with estates in the northwestern Padovano and palazzi in Padua; but by the mid-twelfth century they were overshadowed by the Estensi, the Da Romano, and the Camposanpiero. Descended from noble clans that came to Italy with the Ottonians in the tenth century, these families exploited their wealth and grants of imperial privileges to divide the Padovano among themselves. The Camposanpiero and Da Romano possessed extensive estates and castles northeast of Padua; the Estensi, the leading aristocratic family, took their title from the castle of Este in the southern Padovano. The Estensi acquired the title of marchesi (margraves) of Ancona from Pope Innocent III in 1208 and a permanent urban base as signori (lords) of Ferrara in 1264. Padua shared in the demographic and economic growth of Italy between 1100 and 1300. Although the statistics are necessarily conjectural, it appears that the population of the city more than doubled in this period, from about 15,000 in the late twelfth century to at least 35,000 at the beginning of the fourteenth, putting it in the middle rank of contemporary Italian cities, comparable to Verona, Perugia, and Pavia. In contrast to its neighbor Venice, Padua did not greatly benefit from long-distance trade, with the result that unlike Venice, Genoa, and Florence, it never developed a substantial merchant-banker class. Instead, the wealth of medieval Padua derived from the shrewd exploitation of the contado, its rural hinterland and subject territories, an area of about 260,000 hectares (640,000 acres) that corresponded roughly to the modern civil province of Padua. The rich volcanic soils of the Pedevenda, the Euganean hill country southwest of the city, were intensively cultivated for wine and olive oil; and the plain, once drained, was devoted mainly to arable land and pasturage. Linked to the contado and to export markets in Venice and Chioggia by a system of canals built between 1189 and 1212, Padua served as a market and conduit for the distribution of the region's produce. By the thirteenth century, the city's monopoly of regional trade and the lucrative duties it generated were guaranteed by its political control of the contado and by statutes forbidding competition against the Paduan market.

The nature of the Paduan economy dictated the structure of urban society. Victualers (butchers, taverners, bakers, salt merchants, greengrocers), transport workers (wagoners, bargees), and leather workers (tanners, cobblers, saddlers, shoemakers), all of whom dealt directly in the produce of the contend, made up a majority of the guilds recognized in the statute of 1287. In contrast to the situation in the ancient city, linen workers and merchants dominated the textile sector: the production of woolen textiles did not become a significant factor in the Paduan economy until the fourteenth century. Millers and their sponsors, both private and public, benefited from the water power provided by the Bacchiglione, and Paduan grain and fulling mills attracted business from the surrounding district and from as far away as Venice. The dependence of the city on the resources of the contado created a vigorous market in land, since most Paduans who made their fortunes in trade, usury, or the professions invested their profits in the purchase or leasing of land in the contado. The land market also encouraged the development of a large class of notaries—some 500 by the late thirteenth century—who monopolized the business of drafting and authenticating legal acts; and judges, who dominated the administration of the city and the subject communities of the contado.

Economic growth and feeble imperial control in northern Italy allowed Padua to make the transition to communal government before the mid-twelfth century. The origins of the commune are obscure, but documentary evidence indicates that by 1138 the city was governed by seventeen consuls. In 1164, the commune formed an alliance with Verona, Vicenza, Treviso, and Venice to resist an attempt by Frederick I Barbarossa to enforce imperial judicial and fiscal rights. Three years later, an expanded coalition including Brescia, Mantua, Cremona, and Milan became the first Lombard League, which inflicted a humiliating defeat on Frederick in 1176. Under the peace of Constance (1183), the emperor was forced to recognize the effective autonomy of the communes in matters of internal government, lawmaking, and control of their contadi. Padua joined a revival of the Lombard League in 1226 in opposition to Frederick II's renewal of imperial claims, and a coalition against Frederick II's son Conradin in 1267.

As in other cities where communes evolved, Padua was dominated by established landowning families with a small admixture of the richer urban elements that had begun to emerge by the twelfth century. The appointment of a podestà (chief magistrate) in 1174 may reflect tensions and conflicts within the original ruling class. As a foreigner invested for a limited term with executive and judicial authority, the podestà was supposed to transcend local factions. Nevertheless, according to the chronicler Rolandino, by the end of the twelfth century the city and the region were split by feuds that pitted the Da Romano against the Camposanpiero and the Estensi, and the rural nobility against the urban bourgeoisie. During the first half of the thirteenth century, these rivalries were translated into a struggle for domination of Padua itself. Briefly under the control of Azzo VII d'Este, the city was captured in 1237 and held for twenty years by Ezzelino III Da Romano in the name of Frederick II. The turbulence of the period was reflected in the reconstruction of the old walls enclosing the administrative center of the city (1195-1210)—of which the Porta Altinate and the Porta di Ponte Molino survive—and a castle (La Torlonga) built by Ezzelino in 1237. Opposition to Ezzelino's increasingly arbitrary regime united the rural nobility and the urban communal classes, particularly in the confusion that followed the death of the emperor in 1250. In 1256, a crusade of political exiles sponsored by Pope Alexander IV and led by the Estensi toppled the Da Romano and restored the independence of the commune. Until the death of the free commune in 1318, Padua would usually align itself with the Guelf cause in its relations with other cities.

In Padua, the society of the popolo (the people) was called the comunanza. It originated as a coalition of rich urban citizens and guildsmen who lacked a rural power base and were consequently excluded from the commune. Members organized militia units based on the city's four quarters and bound themselves by an annual oath to defend their common interests, by force if necessary, against the nobles who dominated the commune. Although the early history of the comunanza is obscure, it appears to have been the leading political force in the city by the time Ezzelino seized power, and probably as early as 1200. It returned to a position of control soon after the expulsion of the Da Romano in 1256. The victorious comunanza refrained from abolishing the commune: as the statutory code compiled between 1276 and 1285 shows, the comunanza subordinated the commune by making adherence to the popular coalition a condition of participation in government. The consiglio maggiore ("great council"), the communal legislative assembly, was retained and even expanded in 1277 from 400 to 1,000 members, but participation was restricted to members of the comunanza. The podestà, along with his judicial and administrative staff, continued to be recruited from foreign cities at fixed intervals, but the comunanza ensured its monopoly of power through an armed force of cavalry and infantry and a twelve-man council of anziani (elders). Selected every two months by an assembly of the comunanza, the anziani represented the administrative quarters of the city and eight of the thirty-six guilds recognized by the city statutes. Electors chosen by lot designated the district anziani, and councillors nominated by the outgoing magistrates determined which guilds would elect anziani to speak for the guildsmen. Once appointed, the anziani exercised considerable powers: they reviewed ail decisions of the podestà, controlled the agenda of the council, and reserved the authority to appoint a capitano del popolo ("captain of the people") to defend their interests in a crisis.

Although the regime of late thirteenth-century Padua represented a widening of the political class in response to pressure from below, as much as 90 percent of the urban population, and virtually all of the rural population, was denied access to government. Minimum property qualifications barred wageworkers, peasants, and many minor guildsmen from participation in the council and officeholding. At the other end of the social scale, about twenty noble families were formally disenfranchised by communal statute. The wealth, prestige, and potentially signorial ambitions of such magnati (magnates) were viewed as a threat to the stability of the commune. The few thousand Paduans who enjoyed political privileges represented two distinct classes: guildsmen and nonguildsmen. Despite the preponderance of guildsmen on the board of anziani, the non-guildsmen—mainly judges and representatives of nonmagnate noble families—seem to have exercised leadership by virtue of their social status and administrative expertise. The hegemony of this hybrid ruling class remained largely unchallenged until the early fourteenth century; its internal coherence may be ascribed to a community of interest between the guild and non guild elements, both of which were created and sustained by the economic exploitation of the contado.

The period from 1256 to 1318 was the golden age of medieval Padua. In the absence of external threats to its security and the internal dissensions that led to upheavals and signorial rule in most other Lombard cities, the commune consolidated its hold on the contado and even extended its influence through the annexation of Vicenza in 1266 and Rovigo in 1306. Stability and prosperity found expression in ambitious building programs and a vital cultural life. To this period belong several of the most notable churches and civic monuments of Padua, the refoundation of the university, and the flowering of a civic literary tradition.

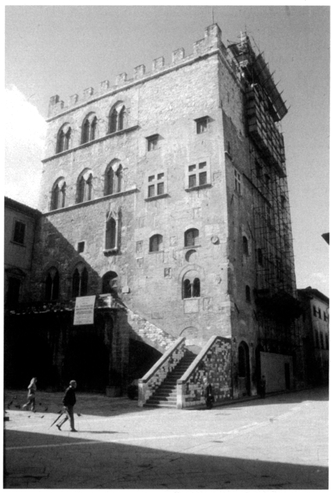

The focus of public life was the Palazzo Comunale, or Palazzo della Ragione, which stands in the city's central market square between the Piazza delle Erbe and the Piazza delle Frutta. Originally built in 1216, it was extensively reconstructed in 1306 by the native architect Fra Giovanni degli Eremitani (fl. 1295-1320), who added the vast upper hall with its ribbed timber roof inspired by Venetian ship design. Measuring about 260 feet long by 89 feet wide by 89 feet high (79 by 27 by 27 meters), the salone (chamber) is the largest and most impressive of extant medieval Italian halls. The fresco cycles illustrating the calendar, the liberal arts, and the religious history of Padua date from the fifteenth century; they replaced earlier frescoes destroyed by fire in 1420 and said to have been painted by Giotto under the direction of the scientist Pietro d'Abano (c. 1250—c. 1316). Also preserved in the hall is the pietra del vituperio ("stone of shame") where bankrupts were publicly humiliated before expulsion from the city. In the communal period, the Palazzo Comunale housed the offices of the podestà and the law courts, while the covered arcades on the ground level served as market stalls. West of the Palazzo Comunale stood the palace of the guilds; and to the east, on the site of the present municipio, there was a complex of buildings constructed or refurbished between 1281 and 1285—of which only a tower remains—that housed the residence of the podestà, the Palazzo degli Anziani, and the Palazzo del Consiglio.

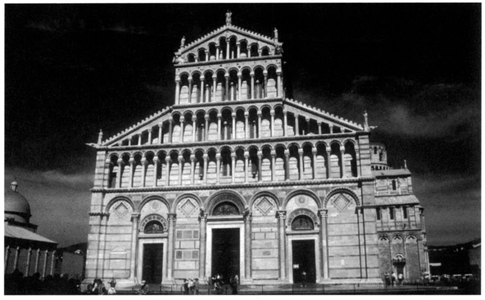

The most conspicuous monument of thirteenth-century Padua is the great pilgrimage basilica of Sant'Antonio, popularly known as the Santo. The basilica was begun in the 1230s to house the remains of the famous Franciscan preacher and theologian, who spent his last years in the vicinity of Padua; it took almost a century to complete. The external arrangement of six domes complemented by a central cupola and two campaniles blends Romanesque, Gothic, and Byzantine elements in a style that is reminiscent of San Marco in Venice. The impressive interior, measuring nearly 380 by 108 feet (115 by 32.5 meters), reflects a similar mixture of influences. The basic plan of a Latin cross with an ambulatory and radiating chapels at the east end is Gothic in inspiration, while the details of the central aisle and choir are Romanesque. With a few exceptions, however, the sculpture and decoration, including the shrine of Sant'Antonio, date from the Renaissance and Baroque periods.

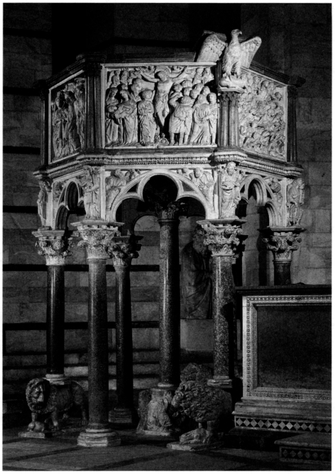

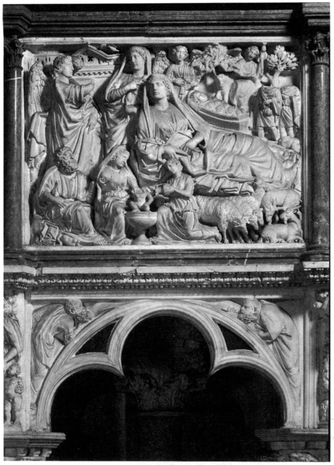

The Eremitani, the church of the Augustinian friars in the northern Ponte Altinate quarter, was built between 1276 and 1306, and the facade was added in 1360. This church was virtually destroyed by bombing in 1944 but has been restored, though most of the medieval decoration is lost, except for fragments of apse frescoes and sculptures. The nearby Cappella degli Scrovegni, or Arena Chapel, contains Giotto's most famous frescoes. The chapel was erected in 1303 in the ruins of a first century amphitheater adjacent to the palace of the Scrovegni, who were among the richest of the "new families" that flourished under the comunanza regime. The donor, Enrico Scrovegni, inherited a fortune from his father, Renaldo, a notorious usurer whom Dante consigned to hell (Inferno, 17.64-75), and the commission was probably intended as a gesture of expiation. If, as some argue, the chapel itself was designed by Giotto, it is the only intact example of a building both planned and decorated by him. The brick structure comprises a simple barrel-vault nave of about 69 by 28 feet (20.8 by 8.5 meters) terminating in a small Gothic sanctuary containing Scrovegni's tomb. Painted between 1304 and 1313, the fresco cycle tells the story of human redemption and final judgement in a series of forty wall panels framed by painted moldings and architectural details. The upper registers on the south and north walls recount the life of Mary; the middle registers recount the life of Christ; and the bottom recounts the history of the passion, the resurrection, and Pentecost. The whole scheme surmounts a painted marble wainscoting broken by monochrome allegorical figures of the seven virtues and vices. The theme of the east wall is the Annunciation, and the choir arch is dominated by a panel of God the father dispatching the angel Gabriel to Mary. The west wall depicts the Last Judgment; among the blessed, Giotto included a portrait of Enrico Scrovegni presenting the chapel to Mary. The frescoes are complemented by statues of the Virgin and two acolytes executed for the altar by the sculptor Giovanni Pisano (d. 1320).

Although there were schools of law and grammar associated with the cathedral in the twelfth century, the studium (university) of Padua traced its history to 1222, when a group of students and masters seceded from Bologna and established schools in the Rudena district in the eastern suburbs of the city. Suppressed or restricted in its activities under Ezzelino, the studium revived with the commune, and its development into an important academic center was actively fostered by the new regime. By 1264, when Pope Urban IV confirmed the statutes of the studium, universities of canon and civil law, a university of arts and medicine, and colleges of doctors of law and arts had been created or refounded. As in Bologna, the universities properly speaking were student corporations that elected their own rectors and teachers. The colleges represented doctors and professors, and controlled admission to degrees. As chancellor, the bishop of Padua exercised formal jurisdiction and conferred degrees, but in practice the university was closely regulated by the commune. In 1262, the commune assumed responsibility for paying the salaries of law professors, and by 1331 it was appointing professors directly, subject only to formal ratification by the student universities. As early as 1261, communal statutes prescribed curricular texts; and the codification of 1285 defined the legal privileges of students and guaranteed them exemptions and protection with respect to lodging, taxation, and loans.

Although Padua was later famous for its medical schools, the medieval university was dominated by law. Medicine was taught along with grammar, rhetoric, logic, and natural science in the arts university, which remained formally subordinate to the jurists' university until the mid-fourteenth century. By 1321, the commune was supporting four professors of medicine and one professor each in surgery, philosophy, logic, and grammar. The foremost arts professor in this period was the physician and astrologer Pietro d'Abano. A native of Padua, Pietro studied in Constantinople and lectured in Paris, where he came into contact with the prevailing Averroist interpretation of Aristotle. He returned to Padua in 1306 to teach medicine and philosophy. His extant writings include several influential translations of Greek medical texts and specialized treatises on poison and physiognomy. Astrology is the central topic of Pietro's two major works, a commentary on the pseudo-Aristotelian Problems and Conciliator, an attempt to reconcile medicine and philosophy. These, along with a series of astronomical treatises by Pietro, testify to the existence of a flourishing school of astrology in early fourteenth-century Padua.

With the overthrow of Ezzelino, a school of distinctly 'civic writing emerged first in the ambience of the university and then among the judges and notaries of the administrative class. Rolandino, the first figure in this tradition, was born in 1200, the son of a notary, and was trained in Bologna, where he was a pupil of the Florentine rhetorician Buoncompagno da Signa. Rolandino appears to have combined a notarial practice in Padua with teaching in the arts university from 1221 until his death in 1276. Cronica, his only surviving work, was read before the university and approved by the masters and doctors of arts in 1262. Inspired by a local tradition of civic annals and the example of Buoncompagno, who had written on Frederick I's siege of Ancona, Rolandino related the history of the Da Romano tyranny from which the city had just been liberated. Tightly written in the rhetorical style of the schools and varied by speeches and diatribes, the Rolandina, as the chronicle came to be known, is a powerful indictment of tyranny and a celebration of communal ideals; it achieved virtually canonical status as an expression of the popular regime's ideology. Despite its popularity, however, Rolandino's chronicle had no imitators: later chroniclers reverted to the spare annalistic style that had prevailed before Rolandino. An exception was the judge Giovanni da Nono, who turned to different models altogether. His Visio Egidii (Vision of Egidius, a legendary king of Padua), written between 1314 and 1318, was inspired by popular pilgrim guides to Rome and is notable as the only topographical description of Padua by a medieval writer. His De generatione aliquorum civium urbis Padue (On the Ancestry of Some Citizens of Padua) drew on noble genealogies and popular legends to construct an unconventional portrait of the city seen through the histories of more than 100 of its most prominent families, ranked according to their status.

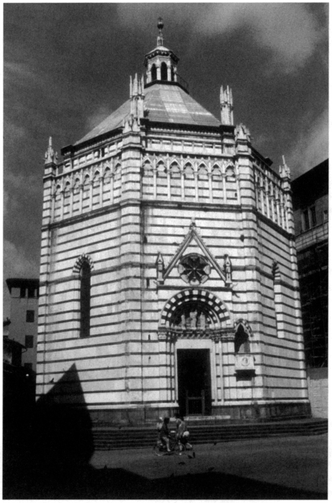

The circle of Latinists that appeared in the last decades of the thirteenth century was significant because it anticipated several characteristics of Petrarchan humanism. As lawyers and notaries, the Paduan "prehumanists" shared the social and professional background of the chroniclers. What distinguished them was their effort to reproduce the vocabulary, style, and cadences of classical Latin in their own writing. Lovato Lovati, the leading figure in the group, was born c. 1240 into a family of notaries, was a communal judge by 1267, was knighted in 1291, and died in 1309 after a successful judicial and administrative career. His literary reputation rests on a series of metrical letters that display a new awareness of classical prosody. The source of Lovato's interests is unclear, but echoes and allusions in his poetry suggest that he was familiar with manuscripts of Tibullus, Martial, Horace, Valerius Flaccus, and Seneca preserved in the libraries of Verona, Pomposa, and Bobbio. Perhaps his most significant accomplishment was deciphering the meter of Seneca's Tragedies, which he explained in a commentary written in the 1290s for the benefit of his circle.

Lovato's disciples and imitators displayed a similar dedication to the classics. Rolando da Piazzola (fl. 1300), Lovato's nephew, was among the first medieval intellectuals to take an interest in recording classical inscriptions. Geremia da Montagnone (c. 1255-1321), whose knowledge of ancient Latin writers rivaled that of Lovato himself, compiled a popular florilegium of classical tags, including extensive quotations from the newly recovered Verona Catullus. However, Lovato's most accomplished disciple, and the writer in whom the Paduan tradition culminated, was Albertino Mussato (1262-1329). The son of a court messenger, Mussato made a meager living as a copyist of university texts until 1282, when he became a notary. By 1296, he had obtained a knighthood and married the daughter of Guglielmo Lemici, one of the richest moneylenders in Padua. The Lemici connection opened the way to politics, and Mussato emerged as a leading figure in communal affairs and diplomacy between 1310 and 1325. Under the influence of Lovato, Mussato explored the contemporary potential of Senecan tragedy and immersed himself in the historical writings of Livy, Sallust, and Caesar. In his tragedy Ecerinis (1314), he resurrected the legend of Ezzelino da Romano to alert his fellow citizens to the threat posed by the territorial ambitions of the signore of Verona, Cangrande della Scala. Although the Senecan meter of Ecerinis made it virtually incomprehensible to its intended audience, the play nevertheless earned Mussato popular acclaim and the distinction of a laurel crown from the university in 1315. The gesture, with its classical overtones, created a sensation in literary circles and inspired Dante, exiled in Verona, to long (in vain) for a similar honor in Florence. Inspired by Livy and Sallust, Mussato's Historia Augusta (Imperial History) and Degestis Italicorum (On the Deeds of the Italians) attempt to explain the contemporary history of Padua by reference to the larger geopolitical realities of Italy: the theme of the Historia Augusta is Henry of Luxembourg's Italian expedition of 1310-1314; and the unfinished De gestis draws a parallel between the decline of the Roman republic and the death of the Paduan commune.

Paduan prehumanism inspired similar movements in Vicenza, Verona, and Venice, but as an indigenous school it perished with the commune. A postscript, however, was provided by Marsiglio Mainardini. Marsiglio was born between 1275 and 1280 and studied in Padua and then in Paris, where he was rector in 1312-1313. He probably studied medicine under Pietro d'Abano after returning to Padua and was associated with Mussato, who wrote a dialogue on Senecan meter at Marsiglio's request and addressed to him a verse letter on the relative merits of medicine and law. Marsiglio left Padua at the time of the first Carrara takeover (1318), but his renowned treatise on government, Defensor pacis (Defender of Peace), which he completed in 1324, reflects the republican ideals of the Paduan circle. Marsiglio was condemned as a heretic for his radical critique, in Defensor, of the temporal power of the pope; he sought refuge in 1327 with Lewis of Bavaria, whom he served as an adviser and court physician until his death in 1342.

Henry VII's expedition initiated a prolonged crisis in Paduan affairs that ended with the abolition of the commune and the establishment of a permanent signoria by the Carrara family in 1328. Before this, however, rifts had begun to appear in the ruling coalition. In 1293, internal divisions caused by the commune's decision to go to war against its traditional allies, the Estensi, provoked fears of a coup by the magnates. Guildsmen reacted by creating an armed "union of the guilds" to protect their interests, and when peace was restored, the union continued to represent a powerful bloc within the comunanza. Under pressure from the union and the council of guild provosts, the board of anziani was expanded to eighteen in order to strengthen the influence of guildsmen in government. The new guild leadership exhibited less deference to Padua's traditional alignments: conflicts with Este Ferrara, in which Padua was supported by the della Scala of Verona, and a war in 1304 against traditionally friendly Venice undermined the old network of Guelf alliances that had favored the independence of the commune.

It was against this background of unsettled regional politics that the emperor, Henry VII, arrived in Italy. Padua felt the effects of his intervention almost immediately when an insurrection erupted in the subject city of Vicenza. In 1311, Vicen tines—backed by Veronese and imperial troops—expelled the Paduan garrison and confiscated Paduan property in the Vicentine contado. When the commune's friendly overtures to Henry failed to prevent his appointment of Cangrande della Scala as imperial governor of Vicenza, Padua joined Florence and other Guelf cities in rebellion. An internal power struggle resulted in the replacement of the anziani and guilds by a twelve-man emergency commission controlled by rich nonguildsmen and professionals led by Albertino Mussato, who immediately set about repairing the commune's links with its former allies. But the early defection of magnate families, combined with the regime's Ghibelline witch-hunts and the failure of its campaign against Cangrande, provoked an uprising in 1314 and a return to the prewar forms of government.

The reestablished commune faced a powerful rival in the Carrara family, which had emerged from the upheavals of 1311-1314 at the head of an influential party in favor of peace. One of the old magnate clans of the southern Padovano, the Carraresi, had declined during the thirteenth century as the family estates were dispersed through inheritance. By the early decades of the fourteenth century, however, the main branch of the family, headed by Giacomo da Carrara, had recouped some of its fortune and influence, which were now deployed to achieve control of the city. In September 1314, Giacomo successfully negotiated a treaty with Cangrande that held until 1317, when the commune made an unsuccessful bid to retake Vicenza. In the ensuing war, Padua was badly defeated, and the terms of a second peace arranged by Giacomo ensured his election as signore in July 1318. His triumph, however, proved ephemeral: undermined by Cangrande, who was determined to incorporate Padua into his own regional empire, Giacomo was forced to barter his signoria to the imperial claimant, Frederick of Austria, in exchange for help against Verona. Submission to the empire bought Padua a brief respite from Veronese aggression, but domestic politics degenerated into bloody factional clashes in the city and magnate revolts in the contado. The death of Giacomo in 1324 unleashed new levels of violence. On the order of Giacomo's nephew Marsiglio, opponents of the Carraresi were murdered or, like Mussato, forced into exile. Unable to secure further German troops, Marsiglio reached an accommodation with Verona. In September 1328, an intimidated consiglio maggiore elected Cangrande della Scala imperial vicar and nominated Marsiglio da Carrara "captain, protector, and general defender" of Padua.

The Carraresi ruled Padua for severity-five years. After 1337, when Florence and Venice helped Marsiglio shake off the della Scala, they governed alone. Francesco I "il Vecchio" stabilized the new order. Elected to the signoria in 1350 following the assassination of his father, Giacomo II, Francesco shared power with his uncle Giacomino until the latter's deposition in 1355, after which he ruled as sole signore until 1388. Granted broad authority by the statute of election, Francesco formalized the concentration of power in the hands of the signore. Under revised statutes of 1362, the podestà became an appointee of the Carraresi, while the anziani and the consiglio maggiore, the latter now stripped of its legislative powers, were reduced to confirming the election of new signori. The guilds lost their independence through subordination to the podestà, who was put in charge of regulating economic activity. The communal administrative apparatus was left intact, but the status of the notaries and judges who had dominated government in the thirteenth century was drastically diminished. Magnate relatives and supporters of the Carraresi monopolized the most lucrative posts, advised the signore, and commanded the new military formations that replaced the communal militia. The Carrara household, which was now the real locus of power, recruited its officials, jurists, and diplomatic secretaries from the upper strata of the citizen class. Through gifts of land and tax exemptions, this privileged group of bourgeois families merged with the old nobility to produce a new, distinctly signorial ruling class.

The Carraresi maintained public sponsorship of the university. Francesco patronized legal studies by endowing a college for destitute law students and importing distinguished law professors, such as the Florentine canonist Lapo da Castiglionchio (d. 1381) in 1379, and Baldus de Ubaldis (c. 1327-1400), who lectured on civil law between 1376 and 1379. The growing distinction of the arts university fueled a dispute with the law component that led to the effective separation of arts and law under Francesco in 1360. Three years later, Pope Urban V completed the evolution of the medieval university when he sanctioned the creation of a faculty of theology from a union of the existing studia of the Dominican, Franciscan, and Augustinian friars.

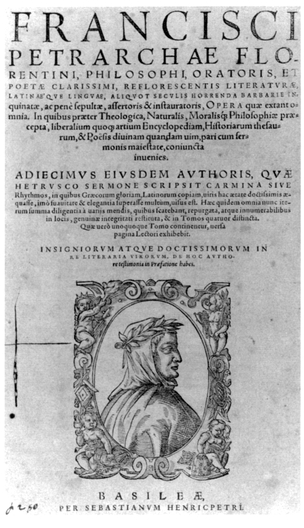

The patronage of the Carrara attracted several humanists to Padua, of whom the most famous was Petrarch (1304-1374). Petrarch was presented with a benefice by Francesco in 1349; and in 1370, near the end of his life, he settled permanently at Arqua in the Euganean hills, where he devoted himself to editing his poetry, his letters, and his incomplete epic on Scipio Africanus. A year before his death he composed, at Francesco's request, an epistolary tract on the duties of a ruler, which is included in his Letters of Old Age. Drawing on classical and patristic sources, Petrarch represented the ideal prince as a benevolent, paternal figure who stood above factional interests and surrounded himself with just advisers. Petrarch sketched an ambitious program of public works, low taxes, and cultural largesse as an alternative to the petty wars that plagued the region, many of which were instigated by his patron. Giovanni Conversini da Ravenna (1343-1408), an admirer of Petrarchan humanism, entered the service of the Carraresi in the 1380s. Under Francesco Novello, he became a professor of rhetoric in 1392 and later chancellor of the university. Conversino's commitment to the Ciceronian ideal of virtus strongly influenced his pupils, among them the founders of the first humanist schools, Vittorino da Feltre (1378-1446) and Guarino da Verona (1370-1460). Similar interests were expressed by Pier Paolo Vergerio (1370-1444), the first theorist of humanist pedagogy. Vergerio was born in Istria and studied in Padua and later in Florence. In 1399, he returned to Padua to lecture on logic in the university. His De ingenuis moribus (On Noble Customs) was written in 1402 or 1403 and addressed to the third son of Francesco il Vecchio, Ubertino, whom Vergerio had probably tutored. The tract departed from medieval precedents by emphasizing the value of the studia humanitatis—particularly history, rhetoric, and moral philosophy—as a preparation for public life. An anticipation of the educational ideals of the humanist schools that soon proliferated in northern Italian princely courts, Vergerio's treatise remained influential throughout the fifteenth century.

A local school of painters inspired by Giotto flourished under the Carraresi. Guariento di Arpo (died c. 1368) and his younger contemporaries, the Veronese Altichiero di Zevio (d. 1395) and the Florentine Giusto de' Menabuoi (d. 1393), were responsible for the most important surviving examples of late medieval painting in Padua. Guariento's earliest extant work is a series of twenty-nine ceiling panels in the former Cappella del Capitano of the Loggia Carrarese, depicting Old Testament themes and the angelic hierarchies. Frescoes of saints Philip, James, and Augustine painted in 1338 are unfortunately all that survive of his cycle in the apse of the Eremitani. On Petrarch's advice, Francesco il Vecchio commissioned portraits of famous Romans for the Sala dei Giganti, part of the original Carrara palazzo incorporated into the sixteenth-century Palazzo del Capitanio. A fragment of the original series portraying Petrarch in his study at Arquà has recently been attributed to Altichiero. In 1379, Altichiero decorated the chapel of San Felice in the south transept of the basilica of SantAntonio with frescoes of the crucifixion. The neighboring Oratorio di San Giorgio, built by the Lupi family between 1377 and 1384, contains the painter's important cycle of the lives of saints George, Lucy, and Catherine. Though much damaged, Giusto's contemporary paintings in the Belludi Chapel of the Santo illustrating episodes from the lives of the apostles Philip and James are, apart from their stylistic importance, vivid evocations of the busy street life of medieval Padua. Giusto was also commissioned by Fina, the wife of Francesco il Vecchio, to decorate the baptistery, which had been constructed in 1171 and renovated in 1260. The cycle is among the most ambitious and complex of medieval Italian fresco programs. Executed between 1376 and 1378, it depicts the Genesis narrative, episodes from the lives of John the Baptist and Christ, and the Apocalypse.

The autonomy of the Carrara lords of Padua was compromised by their early dependence on Venice and by the constant threat of neighboring Verona and Milan. From the beginning of his signoria, however, Francesco il Vecchio pursued an aggressive policy of territorial conquest, financed by heavy taxation, compulsory loans, and arbitrary confiscations, which increasingly alienated his subjects. War with the duke of Milan, Gian Galeazzo Visconti, resulted in a Milanese occupation of Padua in 1388 and the imprisonment of Francesco, who died five years later. Returned to power with Venetian support in 1390, Francesco's heir, Francesco Novello, resumed his father's policy; and when Gian Galeazzo's death in 1402 removed the Milanese threat, Francesco Novello's territorial ambitions brought him into direct conflict with Venice. Deserted by the population of the contado, which had been exhausted and impoverished by decades of conflict, Francesco and his supporters were reduced to maintaining a precarious hold on Padua itself. After a siege of eighteen months, the city fell to the Venetians in November 1405. Francesco was taken to Venice, tried, and later strangled in prison. Other members of the Carrara family were banned from Paduan territory, and their supporters were exiled. The "Golden Bull" of 30 January 1406 formally deprived Padua of its independence and incorporated it into the mainland empire of Venice, of which it would remain a province until 1797.

See also Albertino Mussato; Ezzelino III da Romano; Giotto di Bondone; Lovato dei Lovati; Marsilio of Padua; Petrarca, Francesco; Pietro Abano; Rolandino of Padua; Scrovegni Family; Scrovegni Family Chapel; Universities

LAWRIN ARMSTRONG

Mainardini, Marsiglio. Defensor Pacis, ed. Richard Scholz. Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Leges 7. Hannover: Hahnsche, 1932-1933.

Mussato, Albertino, Ecerinis, ed. Luigi Padrin, trans. Joseph R. Berrigan. Munich: W. Fink, 1975.

Rolandino. Cranial in factis et circa facta Marcbiae Trivixane, ed. A. Bonardi. Rerum Italicarum Scriptores, 8(1). Città di Castello: S. Lapi, 1906.

Statuti del comune di Padova dal secolo XII all'anno 1285, ed. Andrea Gloria. Padua, 1873.

Mainardini, Marsiglio. Defensor pacts, trans. Alan Gewirth. New York: Harper and Row, 1967. (Reprint, Toronto: University of Toronto Press and Medieval Academy of America, 1980.)

Petrarch. How a Ruler Ought to Govern His State, trans. Benjamin G. Kohl. In The Earthly Republic: Italian Humanists on Government and Society, ed. Benjamin G. Kohl and Ronald G. Witt. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1978, pp. 23-78.

Bettini, Sergio, and Lionello Puppi. La chiesa degli Eremitani di Padova. Vicenza: N. Pozza, 1970.

Billanovitch, Guido. "Il preumanesimo padovano." In Storia della Cultura Veneta, Vol. 2, Il Trecento. Vicenza: N. Pozza, 1976, pp. 19-110.

D'Arcais, Francesca. Giotto. New York, London, and Paris: Abbeville, 1995.

Grendler, Paul F. Schooling in Renaissance Italy: Literacy and Learning, 1300-1600. Baltimore, Md., and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989.

Hyde, John Kenneth. Padua in the Age of Dante. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 1966.

—. Society and Politics in Medieval Italy: The Evolution of the Civil Life, 1000-1350. London: Macmillan, 1973.

Jones, Philip. The Italian City-State: From Commune to Signoria. Oxford: Clarendon, 1997.

Kohl, Benjamin G. "Government and Society in Renaissance Padua." Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2, 1972, pp. 210-222.

—. Padua under the Carrara, 1318-1405. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

Lorenzoni, Giovanni. L'edificio del Santo di Padova. Fonti e Studi per la Storia del Santo a Padova, 7. Vicenza: N. Pozza, 1981.

Mommsen, Theodor E. "Petrarch and the Decoration of the Sala Virorum Ulustrium in Padua." In Medieval and Renaissance Studies, ed. Eugene F. Rice. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1959, pp. 130-174.

Mor, Carlo Guido, et al. Il Palazzo della Ragione di Padova. Padua: N. Pozza, 1964.

Semenzato, Camillo, ed. Le Pittura del Santo di Padova. Padua: N. Pozza, 1984.

Simioni, Attilio. Storia di Padova dalle origini alla fine del secolo 18. Padua: G. and P. Randi, 1968.

Siraisi, Nancy G. Arts and Sciences at Padua: The "Studium" of Padua before 1350. Studies and Texts, 25. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 1973.

Stubblebine, James H., ed. The Arena Chapel Frescoes. New York: Norton, 1969.

Waley, Daniel. The Italian City-Republics, 3rd ed. London and New York: Longman, 1988.

Weiss, Roberto. The Dawn of Humanism. London, 1947.

—. "Lovato Lovati." Italian Studies, 6, 1951, pp. 3-28.

—. The Renaissance Discovery of Classical Antiquity. New York: Humanities, 1969.

Wilkins, Ernest Hatch. Life of Petrarch. Chicago, Ill., and London: University of Chicago Press, 1961.

Witt, Ronald G. "Medieval Italian Culture and the Origins of Humanism as a Stylistic Ideal." In Renaissance Humanism: Foundations, Forms, and Legacy, Vol. 1, Humanism in Italy, ed. Albert Rabil. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1988, pp. 29-70.

Paganino da Serezano is an unknown poet of the Duecento; only one of his poems has survived—the canzone Contra lo meo volere. From the place he occupies in the Vatican Codex 3793, between Arrigo Testa and Pier della Vigna, we may infer that he belonged to the oldest generation of the poets of the Sicilian school, and he imitates a practice of Giacomo da Lentini by naming himself in his poem. His exact geographical extraction remains a mystery. The locality is given in the Vatican Codex as Serezano, but MS Rediano 9 (Biblioteca Laurenziana, Florence) proposes Serzana. The identification of a township bearing a name of this configuration is quite difficult. Among the many suggestions are Sarzana in the Lunigiana, Serezano in the Tortonese, and Serezzano in the Versilia region.

See also Giacomo da Lentini; Scuola Poetica Siciliana

FREDE JENSEN

Bertoni, Giulio. Il Duecento. Milan: Vallardi, 1947, pp. 146-147.

Contini, Gianfranco, ed. Poeti del Duecento, 2 vols. Milan and Naples: Ricciardi, 1960, Vol. 1, pp. 115-118.

Lazzeri, Gerolamo. Antologia del pritni secoli della letteratura italiana. Milan: Hoepli, 1954, pp. 563-567.

Monaci, Ernesto. Crestomazia italiana dei primi secoli, new ed., ed. Felice Arese. Rome: Società Editrice Dante Alighieri, 1955, pp. 98-100.

Torraca, Francesco. Studi sulla lirica italiana del Duecento. Bologna: Zanichelli, 1902, pp. 140-141.

Neri di Landoccio Pagliaresi (c. 1350-1406) was one of Catherine of Siena's secretaries and a poet who composed religious lattde, an encomiastic poem about Saint Catherine, and two cantari about spiritual conversion. Neri was born into an aristocratic family of Siena and was a prominent public figure, serving two terms in the general council in 1371 and 1375. It was during these years that he underwent a spiritual conversion and became a devout follower of Catherine. In an undated letter that was probably written in 1371 (Dupreá-Theseider 1940, 7-99) Catherine welcomes Neri to her famiglia. Along with Stefano di Corrado Maconi and Barduccio di Piero Canigiani, Neri became a leading member of Catherine's group, and he quite likely collaborated with her on Libro delta divina dottrina (Fawtier 1921-1930, 1:349). According to several letters and documents, he often accompanied Catherine on important diplomatic missions, such as a mission to Lucca in 1376, when she attempted to dissuade the Lucchesi from joining the antipapal league. As Catherine's ambassador, Neri traveled to Avignon to consult with the pope and was active in the peace negotiations between Rome and Florence in 1378. He learned of Catherine's death while he was on an embassy to the Neapolitan court of Giovanna (Joanna) II in 1380. Neri spent the remaining years of his life in Siena, where he collected Catherine's letters and translated Raimondo di Capua's Legenda maior.

According to Gardner (1907, 85), Neri is a high-strung and sensitive poet, whose laude and cantari are among the best religious poems of the trecento. The Leggenda di Santo Giosafà is a cantare in ottava rima that recounts an Indian prince's conversion to Christianity. It is based on an Iranian tale about Barlaam and josaphat, two names for Buddha. Again using the ottava form, Neri also composed the Istoria di Santa Eufrosina, which narrates the life and death of a virtuous maiden. Conversion is the climactic moment of hagiographical narratives, and it often causes distress among the convert's loved ones. In his poetry, Neri represents the psychological and social conflict caused by spiritual commitment. Because it uses a popular tone and language, his poetry is at once personal and social, as can be seen in the eulogy to Catherine, Spento eà il lume che per certo accese, and in the fifteen laude.

See also Catherine of Siena, Saint

DARIO DEL PUPPO

Dupreá-Theseider, E., ed. Epistolario di Santa Caterina da Siena, Vol. 1. Rome: Istituto Storico Italiano per il Medio Evo, 1940.

Fawtier, R. ed. Sainte Catherine de Sienne (Essais de critique des sources), 2 vols. Paris: De Boccard, 1921-1930.

Gardner, E. G. Saint Catherine of Siena. London and New York: Dent/Dutton, 1907.

Tartaro, Achille. Il Trecento: Dalla crisi dell'età comunale all'umanesimo. Bari: Laterza, 1972, pp. 496-499.

Varanini, Giorgio, ed. Cantari religiosi senesi del Trecento. Bari: Laterza, 1965.

—, ed. Rime sacre di Neri Pagliaresi. Florence: Le Monnier, 1970.

The term "fresco," derived from the Italian for "fresh," is used to denote a variety of techniques for painting wall surfaces, practiced extensively from Roman antiquity through the Middle Ages to the eighteenth century. Though fresco is found all over Europe, this mode of mural painting was best suited to the dry climate of the Mediterranean countries, and its great flourishing occurred in medieval and Renaissance Italy, where from the thirteenth century onward a tremendous proliferation of frescoed images is found.

Two varieties of fresco technique were in widespread use in medieval Italy: buon fresco and fresco secco. Buon fresco, or "true fresco," is a process in which powdered pigments, suspended in water, are applied to a wet, freshly spread lime plaster surface. The damp plaster absorbs the brushed-on pigment like a sponge, and, as it dries, the lime of the plaster forms a chemical bond that fixes the pigment in a crystalline film of calcium carbonate, insoluble in water. The resulting image is one of the most durable paint surfaces known, as the pigment is embedded in the wall itself rather than forming a superficial coating. Fresco secco, or "dry fresco," also uses a plaster ground, but in this case the plaster is allowed to dry before the pigment is applied to the surface through a tempera, oil, or lime-water binder. This technique is necessitated by some pigments, such as lapis lazuli, and it is much easier to execute; but the result is much less durable, tending to flake off over a period of weathering or abrasion.

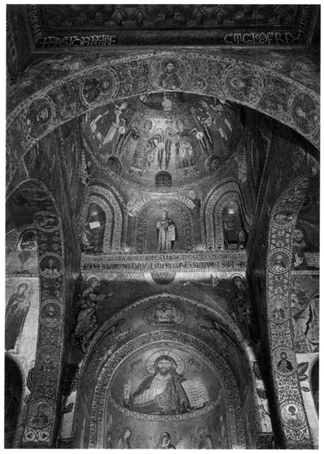

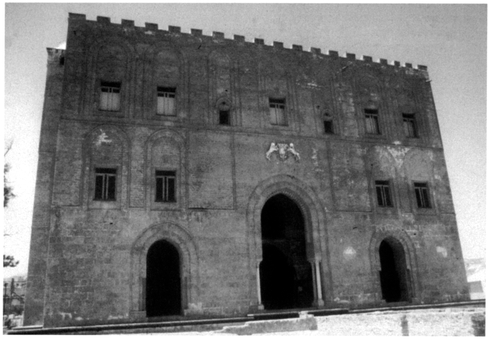

Both techniques were apparently known since antiquity; the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius describes a method of true fresco that is close to the technique spelled out in Il libro dell'arte (The Craftsman's Handbook), a late fourteenth-century shop manual set down by Cennino Cennini, a Florentine pupil of Agnolo Gaddi; and many fresco secco murals survive from Roman antiquity. It seems that fresco secco was practiced continuously from antiquity through the Middle Ages, as all painted wall decorations before the thirteenth century appear to have been executed in the dry manner. True fresco, on the other hand, is not found in Italy before the latter half of the 1200s. This surprising lapse in the use of true fresco has prompted some speculation that the proliferation of buon fresco during the thirteenth century was an independent discovery developed from the craft of mosaic; the technique of mosaic is more closely related to buon fresco than to fresco secco. A number of important mosaic cycles, such as those sponsored by King Roger in Sicily and the doges in Venice, were indeed being executed in the late twelfth century. The quicker, more economical buon fresco technique that appeared immediately following a major period of mosaic activity in Italy may be seen as an innovation spurred on by the economic incentive of making the expensive mosaic technique available to a less wealthy clientele wishing to follow the example of the elite.

The rise in popularity of fresco coincided with the great building boom of the thirteenth century, brought about by a tremendous influx of people seeking employment and security in the cities, and the throngs of worshipers attracted to the church by the popular appeal of the mendicant orders. Before this time few comprehensive mural schemes are found in Italy, with the exception of the few lavish mosaic decorations mentioned above, limited to the most exclusive levels of aristocratic patronage. But the construction of basilicas, cathedrals, town halls, hospices, and oratories in every town along the Italian peninsula occasioned a need for economical, quickly executed, yet durable programs of decoration for which the fresco technique was ideally suited. No cheaper or more effective way existed to raise civic pride through a commemoration of great heroes or events, or to communicate sacred narratives on a scale and level of drama that would thoroughly surround and captivate the viewer.

Much of this decoration was sponsored by the coffers of the church or the state, but a very large proportion was also commissioned by the newly rich and powerful merchant and banking classes, which sought to garner their share of fame and splendor by following the practices of the great ruling houses. Hence, in a form suited to their more modest means, they sought to advertise their place in local society through the commission of privately owned but highly visible chapel or oratory decorations. Entire buildings, such as the Arena Chapel in Padua and the oratory of Or San Michele in Florence, appear to have been designed expressly with mural decoration in mind. The development of large cycles of decoration seems to have received a further boost from a renewed interest, during the late thirteenth century, in the early Christian decorations surviving in many Roman basilicas. In the 1280s and 1290s, for example, the Roman painter Pietro Cavallini was called on to repaint ruined early Christian frescoes in San Paolo Fuori le Mura and old Saint Peter's in Rome; and his own frescoes in Santa Cecilia in Trastevere closely follow early Christian models. Other cycles in the tradition of early Christian models appeared in San Piero a Grado (near Pisa) and the mosaic cycle in the dome of the Baptistery in Florence.

Though buon fresco was rapidly executed, economical, and durable, the actual technique involved was one of the most difficult for a medieval artisan to master and required the mobilization of an entire workshop, if not the hiring of additional help. The first step in the execution of a fresco was the preparation of the wall surface to be painted. Scaffolds large enough to support the team of apprentices and the painting equipment were erected before the bare stone or brick masonry of the structure. Often between 20 and 60 feet (6 to 18 meters) from the ground, the wooden platforms were dismantled and rebuilt from section to section until the entire wall space to be covered was completed. A number of artists are known to have died in accidents associated with these scaffolds. Any pronounced surface irregularities in the masonry were smoothed out to provide an even surface for the fresco, and precautions were taken to ensure that the wall to be painted was protected from moisture and salts, because water seepage into a wall will eventualy crumble the plaster coating.

A layer of rough, gritty plaster, called the arricio, was next laid directly on the masonry, to further smooth out irregularities in the wall surface such as gaps between the stone or brickwork, and to provide a toothy surface which could support the next layer of plaster. Horizontal and vertical plumb lines were snapped onto this layer of arriccio by means of a level and compass. In addition, as was learned from the damage to numerous fresco cycles incurred during World War II and during the flood of the Arno River in Florence in 1966, full-scale sketches of the compositions to be painted were blocked in on the arriccio. Medieval craftsmen may have used small preparatory drawings on paper or parchment to work out a composition, but it seems that most of the designing of frescoes made before the Quattrocento took place in situ, directly on the wall to be painted. The master of the shop would first map out the position, size, and relative placement of the objects to be depicted with very rough charcoal drawings. Once the key compositional relationships were established, the charcoal marks were reinforced with a brush dipped in a solution of red ocher in water, yielding a red drawing called a sinopia, named after Sinope, a city in Asia Minor renowned for its red earth. The provisional charcoal marks were brushed off after the sinopia dried, leaving only the red outline to serve as a compositional guide. Sinopie were never meant to be seen by the general public, but they were one of the most essential steps in the preparation of a fresco, for through them the master was able to estimate and gather together the necessary amount of materials (such as the quantities of colors to be used), prevent architectural settings from being drawn out of plumb, work out the sequence for laying in the final layer of plaster, apportion out various sections to the workshop for execution, and have something to show to the patrons for approval before executing the design.

After completion of the sinopia, another, smoother, much finer layer of plaster, the intonaco, was applied to the arriccio. Before the revival of true fresco painting in the thirteenth century, the intonaco was laid down in very large patches corresponding to the height and length, which could be covered by the artisans working on the scaffold, or ponte; hence these long wide bands of intonaco are called pontate. Only after the pontate were completely dry was the pigment applied with some binder, following the fresco secco technique. In buon fresco, however, in a manner similar to mosaic technique, the fine layer of intonaco is laid in much smaller patches than are used for fresco secco. In true fresco, the pigment bonds solely with wet plaster, thus a medieval craftsman would lay down only as much intonaco over the arriccio as could be painted in a single day's work, before the plaster was dry. Each day's worth of work—called a giornata from the Italian giorno, "day"—would be quickly brushed with pigment before the eight or so hours it took for the plaster patch to dry. The general procedure was to work from the top of a wall down to the bottom, so that dripping or running pigment would not ruin finished work below it. The sizes of giornate vary. Some patches could be quite large, since a relatively open stretch of the composition with few details such as a simple backdrop or a rocky hillside could easily be plastered and painted in a day. Other, more detailed sections tended to be small; a single head with all its features and variations of color could represent an entire day's painting.

The successful coordination of all the giornate into a single coherent image was a difficult task. The pigments available for fresco painting were limited to natural earth colors, such as red and yellow ochre or green terra verde, which would dissolve in lime. Pigments applied to the wet plaster looked different from their final appearance when dry, and the value of color changed depending on how damp the plaster was when the paint was brushed on. Any color that ran across more than one patch had to be applied to the different giornate when they were at the same degree of dampness, but this was difficult to gauge because the time it took for the plaster to dry varied with humidity, temperature, ventilation, and other environmental factors that changed from day to day and season to season. The seams of the giornate were visible in the final image; to mitigate this effect, the workshop tried to hide the borders along the contours of figures or buildings. Furthermore, the plaster patch covered the sinopia of the very section the artist was about to paint, so new drawings, sometimes cut in with a stylus, were made on the intonaco as it was laid down. As time was of the essence in the completion of each giornata, pigments were generally applied with large brushes, and compositions were deliberately designed to be simple and uncluttered to avoid time-consuming detail. If a mistake was made in buon fresco, the area could not be painted over but had to be chipped away and redone. All these considerations demanded an assuredness of hand and a high degree of familiarity with the idiosyncracies of the medium and the pigments used with it. These skills could be gained only from long experience, making the fresco technique one of the most challenging modes of creation ever faced by an artist. It is also a medium which could be realized only by a cooperative, collaborative process of art production, such as that found in the medieval workshops of Italy.

Some evidence indicates that cartoons or full-sized drawings were used during the Trecento to transfer a composition to the wall, although this practice is more typically associated with Renaissance fresco painting. The repeated ornamental border design frescoed in the 1360s by Orcagna's workshop on the entrance arch over the main chapel of Santa Maria Novella in Florence shows patterns of colored dots tracing the outlines of the geometric decoration. These dots were made by holding a cartoon of the design with holes punched in it against the intonaco while charcoal dust was pounced through the holes of the cartoon. Each of the repetitions of the design was made using the same punched cartoon (called a spolvero). Once the cartoon was lifted away, the painter used the pattern of dots as a guide to fill in the colors. Simone Martini's Montefiore Chapel in the lower basilica of San Francesco in Assisi shows a similar utilization of stencils for repeated patterns; and incision marks on certain frescoes such as the Lamentation of Christ in the nave of the upper basilica possibly result from an instrument tracing along the lines of a cartoon held against the damp intonaco.

Very few murals of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries were executed solely in buon fresco. The limited range of the palette and the inhibition of detail in true fresco led to the addition of much a secco work. For example, the blue pigments known to medieval painters, such as azurite and lapis lazuli, are too coarse in grain to be absorbed by fresh plaster, so no true blue pigment was possible in buon fresco. The large expanses of sky and the many depictions of Mary's blue mantle in Giotto's frescoes in the Arena Chapel in Padua all had to be painted on with size (glutinous material) after the plaster dried. More than half of Simone Martini's Investiture of Saint Martin in the Montefiore Chapel in Assisi was painted in tempera over fresco; as a consequence, much of this highly detailed work has flaked away over the centuries. In truth, some medieval frescoes are a composite of all the painting techniques used in the medieval workshop. For example, the closely studied fresco of the Madonna del Cucito (Bologna, Pinacoteca Nazionale) by Vitale da Bologna is a complex combination of buon fresco with tempera and oil glazes overlaid by layers of varnish. Simone Martini, in such frescoes as his Maestà for the Palazzo Pubblico and his Guidoriccio da Fogliano, applied sheets of tin to the intonaco, which he then stamped with punch marks and glazed with transparent veils of color, treating the fresco like a sumptuous panel painting rendered on a monumental scale.

Fresco is unsurpassed in medieval art for its epic sweep of color and form, which graces whole interiors from floor to ceiling; and the technique of fresco painting fostered a boldness of execution and breadth of form that had much to do with the conquest of space and volume in painting by artists in the ensuing Italian Renaissance.

See also Giotto di Bondone; Painting: Panel

GUSTAV MEDICUS

Borsook, Eve. The Mural Painters of Tuscany, from Cimabue to Andrea del Sarto. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980.

Castelnuovo, Enrico, ed. La pittura in Italia: Il Duecento e il Trecento. Milan: Electa, 1986.

Cennini, Cennino d'Andrea. The Craftsman's Handbook, trans. Daniel V. Thompson, Jr. New York: Dover, 1954.

Cole, Bruce. The Renaissance Artist at Work: From Pisano to Titian. New York: Harper and Row, 1983.

The Great Age of Fresco: Giotto to Pontormo. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1968. (Exhibit catalog.)

Meiss, Millard. The Great Age of Fresco: Discoveries, Recoveries, and Survivals. New York: George Braziller, 1970.

Procacci, Ugo. Sinopie e affreschi. Milan: Electa, 1961.

Thompson, Daniel V„ Jr. The Materials and Techniques of Medieval Painting. New York: Dover, 1956.

Vasari, Giorgio. Vasari on Technique, trans. Louisa S. Maclehose. New York: Dover, 1960.

In Italy painting in manuscripts has a history that reaches back to antiquity (Weitzmann 1977). During the early Middle Ages this medium, referred to as manuscript illumination or miniature painting, was transformed by the requirements of the Christian liturgy and the shift from the roll to the codex in late antiquity, just as it was transformed by the introduction of the printed book at the end of the Middle Ages. Yet it is certainly valid to speak of "Italian" medieval miniature painting. Despite Italy's religious and political connections to the rest of Europe, the evolution of its manuscript painting follows a distinctive pattern determined in part by its location between northern Europe and the Byzantine empire. Significant, too, from the twelfth century on was the increasing understanding of the human figure and of space, fostered in part by the connections between manuscript illuminators and panel and wall painters (Alexander 1994, 121-122). These and other consistencies crossed political boundaries within a peninsula divided among different rulers, including the Lombards, the Byzantine empire, the papacy, and the Norman kings of Sicily; individual city-states such as Lucca, Pisa, Florence, Siena, Venice, Bologna, and Arezzo; and local rulers and powerful families.

These, in fact, as intersections of economic prowess and individual or group ambition, whether political or religious, were the sites of major manuscript production—for manuscript illumination was an expensive undertaking. Indeed, along with the analysis of palaeography and codicology and the identification and localization of decoration styles, the study of Italian manuscript illumination raises numerous contextual problems. For example, scholars have investigated the motivation behind the production of manuscripts. In the early Middle Ages, the primary producers of manuscripts were monasteries and court ateliers, and while some of the texts were classical and secular, the vast majority were liturgical texts and Bibles. Later, the development of cities, the emergence of the universities, and changes in the liturgy meant that new texts—such as the Missal, the one-volume Bible, and the Decretals of Gratian—were produced and new types of patrons emerged. The style of an individual painter or atelier, or even a region, might be affected by the agendas of patrons, and their political, religious, or familial alliances. And there are other questions. Who were the artists (Alexander 1994, 4-34)? Were they also the scribes? Were they monks? Were they professional artists, working alone or in highly organized ateliers? On which projects did artists copy from valued exemplars? For which did they invent new programs of illustrations based on motifs book and written instructions (Alexander 1994, 52-71, 121-149)? Were court painters and ateliers common or rare? How far did artists travel? Some painters working in Italy appear to have been from England or from Byzantium, and documents in Naples in the thirteenth century refer to Mainardo Teutonico, who might have been German (Daneu Lattanzi 1978, 150; Evans and Wixom 1997, 479-481, 486). What does it mean when Italian artists appear to imitate aspects of the style of manuscripts produced in other political centers, such as Byzantium or Paris (Toubert 1980)? The following episodes from the history of Italian medieval manuscript illumination address these issues and others.

Although it is clear that manuscripts with narrative sequences were produced in Italy in the fifth and sixth centuries, as Backhouse has noted, "comparatively few miniatures of high quality survive from Italy" in the early Middle Ages (1979, 22). Certainly, the likelihood that the Codex Grandior—a huge one volume Bible—was among the books Benedict Biscop purchased in Rome and brought back to England in the seventh century indicates that Italian manuscript production was important during this period (De Hamel 1994, 17-21). A manuscript that does remain to us is the so-called Gospel of Saint Augustine or Cambridge Gospel (Corpus Christi College, MS 286), apparently one of the many codices sent by Gregory the Great to Saint Augustine to aid in bringing Christianity to the English in 596 (De Hamel 1994, 17). And an illustrated medical anthology attributed to Monte Cassino or southern Italy (Florence, Laurentian Library MS Plut. 73,41) survives from the early ninth century (Belting 1968, 122-132; Robb 1973, 163-164).

Despite these indications that Italy played an important role in the emergence of medieval manuscript ornamentation and illustration, it is in the tenth and eleventh centuries that we begin to see impressive and distinctive groups of illuminated manuscripts there. Three of the most prominent groups are the Beneventan school, best-known for the production of exultet rolls, the manuscripts of Monte Cassino, and the so-called Atlantic Bibles usually associated with Rome. One characteristic they share is a relationship to northern European manuscript illumination, especially in their ornamented initials.

Among the earliest Italian illuminated manuscripts are some of the approximately thirty-three remaining exultet rolls produced in southern Italy, which date from the tenth century to the fourteenth (Avery 1936; Belting 1968, 144-183, 234-255; Cavallo 1973 and 1994; Evans and Wixom 1997, 469-472; Speciale 1991). These are unique Italian liturgical manuscripts which include the text of the hymn for the Easter vigil, Exultet iam angelica turba coelorum. Among the oldest are three that were originally attributed to a scriptorium at San Vincenzo al Volturno, but have more recently been attributed (Belting 1968, 154) to Benevento itself, between 985 and 987. Because of the history of the region, these manuscripts include varying degrees of Byzantine content in a figure style that is recognizably southern Italian. Some of these manuscripts are far more Byzantine in figure style and also have more elaborate ornamental repertoires, for example an exultet roll (Bari, Cathedral Archives, Exul tet 1) and a benedictional (Bari, Cathedral Archives) made in eleventh-century Bari, which was the administrative capital of a Byzantine province in Italy beginning in 969 (Belting 1974, 14-19; Mayo 1987, 386-387).

Shortly after the production of the manuscripts at Bari, another group of southern Italian manuscripts was executed at Monte Cassino, where Abbot Desiderius's new basilica was dedicated in 1071. The scriptorium produced manuscripts that combined the now familiar southern Italian or Beneventan palaeographic and ornamental styles with an increasing absorption of iconographic and stylistic elements from Byzantine painting (Cavallo 1989). These Monte Cassino manuscripts include two homiliaries (Monte Cassino 98 and 99), as well as a lectionary (Vat. Lat. 1202) in the Vatican (Adacher and Orofino 1989; Newton 1979). Their southern Italian initial and ornamental style contains foliate trellises and an interlace inhabited by birds and canines. Scholars have noted that this ornamental style must have been affected by the presence of Carolingian and Ottonian manuscripts in Italy, sent as gifts by emperors, including the Vatican's Gospel of Henry II (MS Ottob. Lat. 74), which was given to Monte Cassino by Henry c. 1022 (Ayres 1994b, 134; Robb 1973, 171).

Another cluster of important manuscripts was the so-called Atlantic Bibles, generally localized to Rome, which take their name from their colossal size (Ayres 1994a, b). These manuscripts, which have been associated with wall painting, are especially noted for their full-page Creation cycles, perhaps best seen in the twelfth-century Pantheon Bible (Vat. Lat. 12958) in the Vatican Library (Garrison 1953, 1.1, 83-89; 1955, 2.1, 21-44; 1961, 4.2, 117-178). The study of these codices involves considering Old Testament iconography, sorting attributions and localizations, and analyzing the relationships between Italian manuscripts and both transalpine and Byzantine painting (Ayres 1982 and 1994a, b). Other Roman manuscripts such as the Saint Cecilia Evangeliary (Florence, Laurentian Library, Cod. 17, 27), have been discussed by Garrison (1955, 2.1, 36-38).

A twelfth-century Umbro-Tuscan style that combined some of the elements discussed above has been studied extensively by both Garrison and Berg, who described its initials as "geometrical," a type they traced to eleventh-century Rome (Berg 1968, 19; Garrison 1953, 1.1, 19-32 and 1954, 1.4, 159-175; La pittura in Italia 1985, 2:549). Consisting of ornamented shafts derived from northern European painting, the initials combine repeated rosettes and tight foliage in their interstices. They are embellished with gold leaf and, most significantly, with white vine foliage with half leaves, a form of decoration that became a permanent element of Italian manuscript illumination. A superb group produced at Pisa includes the brilliant Calci Bible (Certosa di Calci Cod. 1). In its decoration are figures copied closely from Byzantine manuscripts (Berg 1968, 146—168, 224—227; Garrison 1955, 2.2, 97-111).

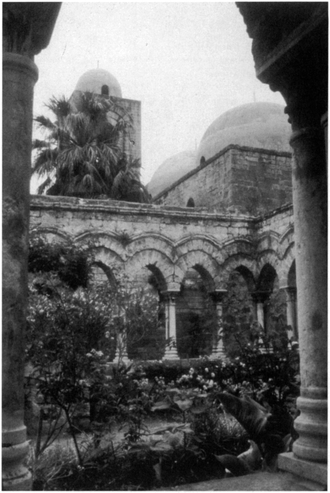

In twelfth-century Sicily, a striking group of manuscripts was produced partly in response to the patronage of a powerful churchman whose political interests promoted a combination of Byzantine and Italian painting. Many are now in the Biblioteca Nacional in Madrid, but on the basis of their provenance and litanies, these manuscripts are usually attributed to Messina, during the archbishopric of the Englishman Richard Palmer in the second half of the twelfth century (Andaloro 1995, 357—378; Buchthal 1955; Daneu Lattanzi 1968, 15-33; Owens 1977). Among the most spectacular of these codices is a sacramentary, Madrid MS 52 (Evans and Wixom 1997, 479-481; Pace 1977). The ornamental style of twelfth-century Sicilian initials combines the Italian geometrical initial with elements of Byzantine ornamental repertoire and figure style (Buchthal 1955 and 1956).