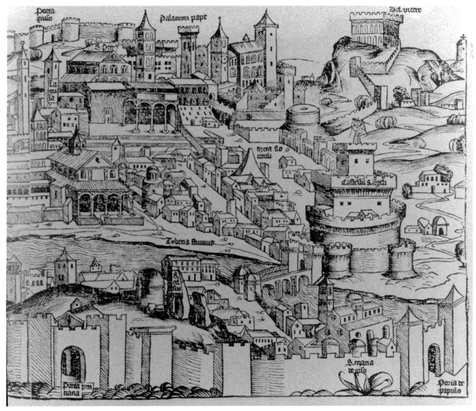

Radagaisus. Hartmann Schedel, Liber chronicarum (Nuremberg Chronicle). Nuremberg: Anton Koberger, 1493, p. 135v.

Rabanus Maurus (c. 780-856) was a teacher, scholar, writer, and active churchman whose career reflects the Carolingian renaissance. He was born at Mainz, and as a boy he became an oblate at the monastery of Fulda. In 802, he was sent briefly to Charlemagne's court and then to Tours to study with Alcuin, who was the leading figure in shaping Charlemagne's program to revive education and learning. Rabanus returned to Fulda before 804, became master of the monastic school, and then in 822 became the abbot. As abbot, he not only promoted the monastic school, library, and scriptorium but also built churches, carried on pastoral work, and managed the abbey's extensive properties. As a consequence, Fulda grew to be a major center of learning in the Frankish world and constitutes a case study of the nurture of learning in local centers remote from the Carolingian court. Rabanus was a supporter of Louis I the Pious and Louis's eldest son, Lothair (Lothar) I, as representatives of the ideal of imperial unity, a position that cost him his abbacy in 842 during the fraternal struggles following the death of Louis in 840. In 847 Rabanus was elected archbishop of Mainz, and until his death he utilized that office to promote church reform, defend doctrinal orthodoxy, and support missionary activity.

Rabanus was i he most prolific of all Carolingian writers. He produced a huge body of literary works in many forms: scriptural commentaries, basic textbooks on the liberal arts {De arte grammatica and De computo), penitentials, collections of sermons, a martyrology, poems, and letters, some of which reflected his views on current political and theological issues. Perhaps his most influential works were De institutione clericorum, a manual for priests dealing with the nature and exercise of their office and with the education required to prepare them for their duties; and De rerum naturis, an encyclopedia seeking to provide the basic knowledge required to read and interpret scripture in a spiritually fruitful way.

Rabanus's literary works are primarily compilations drawn from earlier writers, and so he has received little credit as an original thinker among modern scholars. However, this evaluation misses the inspiration that guided his intellectual, literary, and pastoral career. Deeply imbued with the fundamental concept guiding the Carolingian renaissance, Rabanus believed that the challenge facing his age was the recovery in usable form of the basic wisdom that defined the true Christian religion. This wisdom—enshrined in scripture, the vast body of Latin patristic writing, and even Latin pagan literature—needed to be sorted out and organized so that it could be learned and applied by his contemporaries. To what was essentially a pedagogical task, Rabanus brought considerable talent: extensive learning, a sense of essentials, skill as an organizer of borrowed materials into straightforward works of instruction, and an ability to adapt received knowledge to new situations. His corpus of writings indicates one of the major accomplishments of the Carolingian renaissance: the reestablishment of fruitful contact with a rich and complex tradition. For his contribution to the Carolingian revival of learning, he perhaps deserves a title given him by modern scholars, preceptor Germaniae.

See also Charlemagne; Frankish Kingdom; Louis I the Pious

RICHARD E. SULLIVAN

B. Rabani Mauri Fuldensis Abbatis et Mogunti Archiepiscopi Opera Omnia, 6 vols. In Patrologia latina, ed. J. Migne, Vols. 107-112. Paris, 1864-1878.

Hrabanus Maurus: Lehrer, Abt und Bischofi ed. Raymund Kottje and Harald Zimrnermann. Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur. Mainz: Abhandlungen der Geistes- und Sozialwissenschafdichen Klasse, Einzelveröffentlichung, 4. Mainz and Wiesbaden: Steiner, 1982.

Kottje, Raymund. "Hrabanus Maurus." In Lexikon des Mittelalters, Vol. 5. Munich and Zurich: Artemis Verlag, 1990, cols. 144-147.

Peltier, H. "Raban Maur." In Dictionnaire de théologie catholique, Vol. 13. Paris: Latouze et Ané, 1937, cols. 1601-1620.

Rissel, Marie. Rezeption antiker und patristischer Wissenschafi bei Hrabanus Maurus: Studien zur karolingischen Geistesgeschichte. Lateinische Sprache und Literatur des Mittelalters, 7. Bern: Herbert Lang; Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 1976.

Radagaisus (d. 406) was a pagan Goth who crossed the Danube and invaded Italy in 405-406. He met with little resistance there, and he had forced the city of Florence to the point of surrender when the Roman regent Stilicho arrived with relief troops. Stilicho forced Radagaisus and his army to withdraw from Florence to Fiesole and then cut off their supply line. Consequently, Radagaisus was starved into submission. When Radagaisus tried to abandon his soldiers, he was captured by the Romans and executed outside the gates of Florence on 23 August.

Radagaisus. Hartmann Schedel, Liber chronicarum (Nuremberg Chronicle). Nuremberg: Anton Koberger, 1493, p. 135v.

See also Stilicho

JENNIFER A. REA

Heather, Peter. Goths and Romans: 332-489. Oxford: Clarendon, 1991.

Martindale, John. The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire, Vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980.

The troubadour Raimbaut de Vaqueiras (c. 1155or 1160-1207) was born in Vacqueyras, near Orange in Provence, and probably died near Messinople in Thrace (northern Greece). He was of lowly origins and soon adopted the profession of jongleur. Since during this period the courts of Provence were somewhat lukewarm in their patronage of poets, he tried his luck on the other side of the Alps, where the lords of Montferrat, Malaspina, and Este were vying with each other to welcome troubadours and jongleurs. In particular, the brilliant court of Montferrat, where Raimbaut arrived in the 1180s, was very hospitable to exponents of the new poetry; and he soon formed a bond of sympathy with the marquis's third son, Boniface, who was about his age. In due course this ripened into one of the most intimate and affectionate associations ever recorded between a poet and his patron, which was not severed until Boniface's tragic death in 1207. Before reaching Montferrat, Raimbaut had been forced to wander, on foot and hungry, across the plains of Lombardy, as he recalled in a famous tenso with another troubadour, Albert of Malaspina. Afterward, as a close friend of the marquis, Raim-baut fought valiantly alongside his patron on several occasions and was instrumental in saving Boniface's life during a Sicilian campaign of 1194 for Emperor Henry VI, a feat that earned him a knighthood. In the spring of 1203, Raimbaut went on the Fourth Crusade, joined the marquis and the Venetians on their way to Constantinople, and was wounded during the ensuing siege. After the conquest of Constantinople in 1204, Raim baut accompanied Boniface on a campaign in Greece; later he participated in the activities of Boniface's court at Salonika. Raimbaut very likely died with his friend during Boniface's ill-advised incursion into the Rhodope Mountains, on 4 September 1207.

Raimbaut left twenty-six poems, of which eight are preserved with musical notation. His multilingual descort is particularly famous: one stanza is in Occitan, another in Italian, a third in French, a fourth in a kind of Gascon, a fifth in a type of Gal-lician-Portuguese, and a sixth in a combination of the five languages, each having two lines. The lyric-epic composition called Carros, which described an imaginary war of merit, beauty, and youth between his patroness—Boniface's sister Beatrice—and a band of more than twenty ladies of the Italian nobility, is no less famous and is one of the jewels of Occitan literature. Another fine composition, completed in 1205 in Greece, is his Epic Letter (its modern title). This work is unique in the Romance literatures of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries: it consists of three poems rhyming -at, -o, and -ar and contains a request to the marquis for material compensation for his services, concomitantly serving as an autobiography.

HANS-ERICH KELLER

The Extant Troubadour Melodies, ed. Hendrik van der Werf and Gerard A. Bond. Rochester, N.Y.: Van der Werf, 1984, pp. 289-298.

The Poems of the Troubadour Raimbaut de Vaqueiras, ed. Joseph Linskill. The Hague: Mouton, 1964.

Bertolucci Pizzorusso, Valeria. "Posizione e significato del canzoniere di Raimbaut di Vaqueiras nella storia della poesia provenzale." Studi Mediolatini e Volgari, 11, 1963, pp. 9-68.

Brugnolo, Furio. Plurilinguismo e lirica medievale da Raimbaut de Vaqueiras a Dante. Rome: Bulzoni, 1983.

Crescini, Vincenzo. "La Lettera Epica di Rambaldo di Vaqueiras." Atti e Memorie della R. Acc. di Scienze, Lettere, ed Arti in Padova, n.s., 18, 1901-1902, pp. 207-230.

Zingarelli, Nicola. "Bel Cavalier e Beatrice di Monferrato." In Studi letterari e linguistici dedicati a Pio Rajna nel quarantesimo anno del suo insegnamento. Florence: Tipografia E. Ariani, 1911, pp. 557-575.

Rainulf (Ranull Drengo, died c. 1045) was the leader of a band of Norman mercenaries who would establish the first permanent Norman principality at Aversa. Having landed in southern Italy with his brothers in 1016, Rainulf eventually placed himself and his followers at the service of various Lombard princes who in one way or another were determined to expand their principalities at the expense of the Byzantine empire, which maintained more than a nominal control over the south. At some point, Rainulf placed himself at the service of Pandulf IV, prince of Capua, who, taking advantage of the death of Guaimar IV of Salerno and the minority of Guaimar V, proceeded in 1027 to take over Naples and remove the ruling duke, Sergius IV (d. 1037). Later, Rainulf, having married the sister of Duke Sergius, helped Sergius to regain Naples. For this Service, in 1029, Rainulf was granted the village of Aversa; when fortified, it became a strong defensive outpost for Naples and also the base for the Normans' expansion in southern Italy, a rallying point for incoming Normans seeking employment as mercenaries.

After the death of his first wife, Rainulf married the niece of Pandulf IV of Capua and thus returned to the service of Pandulf. But when Conrad II (r. 1024-1039) moved southward to rearrange the political order there, Rainulf once again switched allegiance, giving his support to the prince of Salerno, Guaimar V. In 1038, Conrad recognized Guaimar as prince of Salerno and Capua and invested Rainulf as count of Aversa. Rainulf assisted Guaimar in the conquest of Amalfi in 1039 and Gaeta in 1040. In the campaigns against the Byzantines, the Normans fought alongside the Lombards, and although the Normans were still only allied mercenaries, they were responsible for a series of victories. The Normans would eventually assume the leadership of the Apulian revolt, but Rainulf himself died in June of 1044 or 1045.

See also Aversa; Conrad II; Normans; Sergius IV, Duke of Naples

ANTHONY P. VIA

Chalandon, Ferdinand. Histoire de la domination normande en Italie et en Sicilie, 2 vols. Paris: Libr. A. Picard et Fils, 1907.

Loud, G. A. The Age of Robert Guiscard: Southern Italy and the Norman Conquest. Essex: Pearson Education, 2000.

Rangerius (d. 1112) was bishop of Lucca from c. 1096 until his death. He was a talented literary writer in Latin and a vigorous champion of the Gregorian reform. His life before August 1097, when he first appears in the Lucchese charters, is a mystery: his nationality (perhaps French), his training, his possible monastic vocation, and even the date of his election as bishop are all controversial. Most of our evidence for Rangerius is derived from his two surviving poems, whose considerable stylistic merits have commanded far less attention than their utility as historical sources.

Vita metrica s. Anselmi lucensis episcopi (Metrical Life of Saint Anselm, Bishop of Lucca) was presumably written between 1096 and 1099. It is an elegant treatment, in 3,650 elegiac distichs, of the life and deeds of Rangerius's recent but not immediate predecessor, the reforming bishop Anselm of Lucca; and it is valuable as a document of the ecclesiastical history of Lucca and also for the light it sheds on attitudes toward the role of the church in late eleventh-century Lucchese society. De anulo et baculo {On the Ring and the Staff) was seemingly written in late 1110; it is in 530 elegiac distichs and constitutes a reply to a recent treatise upholding imperial rights in the investiture of bishops. In this work, Rangierus focuses mainly on the sacramental nature of the staff and the ring presented during the investiture ceremony and offers an eloquent affirmation of the freedom of the church from lay (and especially royal) interference. According to Donizo of Canossa, who quotes verses that are absent from the text as transmitted, the poem was dedicated to Matilda of Tuscany; but as we have it now, it is addressed to the papal chancellor John of Gaeta (the future Pope Gelasius II).

At least two prose writings have also been ascribed to Rangerius: a sermon on the translation, in 1109, of the remains of the martyrs Regulus, Jason, Maurus, and Hilaria; and a sermon on the dedication of the church of Saint Martin (Lucca's cathedral, dedicated 6 October 1070). The first sermon, whose most authoritative form has been edited only in part, is probably Rangerius's work and has been accepted as such by at least one relatively recent scholar; the other attribution, however, has found little support.

See also Latin Literature; Lucca

JOHN B. DILLON

De anulo et baculo, ed. Ernst Sackur. Monumenta Germaniae Historica Libelli de Lite Imperatorum et Pontificum, 2, pp. 505-533.

Guidi, Pietro. "Per la storia della cattedrale e del Volto Santo (note critiche)." Bollettino Storico Lucchese, 4, 1932, pp. 169-186. (Attributed sermons. See especially pp. 182-186.)

Vita metrica s. Anselmi lucensis episcopi, ed. Ernst Sackur, Gerhard Schwartz, and Bernhard Schmeidler. Monurnenta Germaniae Historica SS, 30(2), pp. 1152-1307.

Guidi, Pietro. "Delia patria di Rangerio autore della 'Vita metrica' di s. Anselmo vescovo di Lucca." Studi Gregoriani, 1, 1947, pp. 263-280.

Nobili, Mario. "Il 'Liber de anulo et baculo' del vescovo di Lucca Rangerio, Matilde, e la lotta per le investiture negli anni 111 0— 1111." In SantAnselmo vescovo di Lucca (1073—1086) nel quadro delle trasformazioni sociali e della riforma ecclesiastica, ed. Cinzio Violante. Istituto Storico Italiano per il Medio Evo, Nuovi Studi Storici, 13. Rome: Nella Sede dell'Istituto, 1992, pp. 157-206.

Savigni, Raffaele. "L'episcopato lucchese di Rangerio (1096-c. 1112) tra riforma 'gregoriana' e nuova coscienza cittadina." Ricerche Storiche, 27, 1997, pp. 5—37.

Severino, Gabriella. "La Vita metrica di Anselmo da Lucca scritta da Rangerio: Ideologia e genere letterario." In Sant'Anselmo vescovo di Lucca (1073-1086) nel quadro delle trasformazioni sociali e della riforma ecclesiastica, ed. Cinzio Violante. Istituto Storico Italiano per il Medio Evo, Nuovi Studi Storici, 13. Rome: Nella Sede dell'Istituto, 1992, pp. 223-271.

Ratchis was a king of the Lombards (r. 744-749). He had been made duke of Friuli, succeeding his father, Pemmo, by King Liutprand. In 744, Ratchis overthrew Liutprand's successor, Hildeprand. As king, Ratchis inherited the strong realm created by Liutprand, and he continued Liutprand's policy of expansion at the expense of the empire. Although Ratchis was successful in a number of projects, he faced an increasingly serious situation as the popes succeeded in breaking a long-lasting friendship and cooperation between the Lombards and the Franks, and the Lombard dukes became increasingly restive under strong royal control. Ratchis was overthrown by his brother Aistulf in 749, whereupon Ratchis retired to the monastery of Monte Cassino. He emerged briefly in 756 in an unsuccessful attempt to regain the throne.

See also Aistulf; Liutprand; Lombards

KATHERINE FISCHER DREW

Hallenbeck, Jan T. Pavia and Rome: The Lombard Monarchy and the Papacy in the Eighth Century. Philadelphia, Pa.: American Philosophical Society, 1982.

Noble, Thomas F. X. The Republic of Saint Peter: The Birth of the Papal State, 680-825. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1984.

Wickham, Chris. Early Medieval Italy: Central Power and Local Society, 400-1000. Totowa, N.J.: Barnes and Noble, 1981.

Ratherius, bishop of Verona (Rather of Luttich, c. 887 or 888-974), was born in Germany. In 926 he went to Italy, where he found favor with Hugh of Aries, who, in addition to his Provencal holdings, had just become king of Italy. Ratherius became bishop of Verona in 931. Unfortunately, he sided with Arnulf of Bavaria when Arnulf invaded Italy in 934. Hugh defeated Arnulf and imprisoned Ratherius for two and a half years.

Ratherius wrote his greatest work, Praeloqua, in prison, as a guide for those beset by suffering. His contemporary Liudprand of Cremona praised it, but some modern critics believe it is marred by self-pity.

See also Latin Literature; Verona

MARTIN ARBAGI

The Complete Works of Rather of Verona, trans., intro., and notes Peter L. D. Reid. Binghamton, N.Y.: Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies, 1991.

Ratherius Veronensis. Praeloquiorum libri VI, Phrenesis, Dialogus confessionalis, Exhortatio et preces, Pauca de vita Sancti Donatiani, fragmenta nuper reperta. Curante CETEDOC, Universitas Catholica Lovaniensis (Louvain, Belgium) Lovanii NovL Turnhout: Brepols, 1984. (Microfiche.)

Reece, Benny R. Learning in the Tenth Century. Greenville, S.C.: Furman University Press, 1968.

Reid, Peter L. D. Tenth-Century Latinity. Rather of Verona. Malibu, Calif.: Undena, 1981.

Ravenna is strategically situated along the land corridor of eastern Emilia between the Po valley and the Via Flaminia as it passes southward through the great barrier of the Apennines; thus the city commanded the historic passage between old Cisalpine Gaul and Italy proper. It could be made virtually impregnable because it was erected in the tidal marshes inward from the Adriatic shore—"built entirely on piles, and traversed by canals which you cross by ferryboats," as the Greek geographer Strabo (first century B.C.) describes it, almost anticipating Cassiodorus's depiction of the Venetian lagoon. Ravenna was the southernmost base of Julius Caesar's proconsular realm, and from it he marched south to cross the boundary of his province, the Rubicon River, to confront the senate in 49 B.C. Octavian (Augus tus)—recognizing the needs of the Roman navy, and appreciating Ravenna's location—used it as a maritime base during the civil wars and then created the new port of Classis ("Fleet"), more than 2 miles (3 kilometers) southeast of the town, as one of the empire's major naval stations. Between Classis and Ravenna proper a suburb known as Caesarea developed.

Through the early history of the empire, Ravenna apparently grew and prospered. Christianity is said to have come to it as early as the first century after Christ, and tradition holds that Saint Apollinaris, a Syrian-born disciple of the apostle Peter, became its first bishop (and possible martyr). A later bishop, Ursus (r. 370-c. 396), is credited with building the first Christian church in Ravenna (c. 385). Though Ravenna played a role in the recurrent military crises of the second and third centuries, its facilities may have already begun to decay, as its shore silted up. However, its decline, if any, would have been suddenly arrested in 402, when the young Theodosian emperor Honorius (r. 395-423) decided to transfer his court to Ravenna from Milan, which was then the imperial capital. This step has been explained as resulting from Honorius's sense of vulnerability at the time of Alaric's entry into Italy, but it also very sensibly took into account the comparative security and defensibility of Ravenna as a seat of government. Thus, in the confusion following the fall ofStilicho in 408, and despite the collapse of military organization that allowed Alaric's rampage through Italy and his symbolically devastating sack of Rome in 410, Ravenna remained the inviolate governmental center from which order could be reestablished.

Another of Ravenna's assets was its immediate access to the Adriatic as a route of possible aid from the eastern court of Constantinople. Its value was demonstrated when an eastern force was sent to depose a usurper who had seized power after Honorius died childless, and to establish as his successor his young nephew, Valentinian III (r. 425-455). Valentinian, though, was a worthless prince, whose mother, Gaila Placidia (Honorius's sister), was the actual ruler until her death in 450. She preserved Ravenna as functioning capital, adorning the city with new buildings. During her regime, and under its prelate Peter Chrysologus (from 432 to 450), the see of Ravenna replaced that of Milan in jurisdiction over neighboring bishoprics.

Galla Placidia also maintained ties with Rome, where her son held his court; indeed, it was in Rome that she died and was buried. During the tumultuous third quarter of the fifth century, which witnessed the final debasement and destruction of the empire's western court, Rome alternated with Ravenna as the focus of events, but it was in Ravenna that the last western emperor, the boy Romulus Augustulus (r. 475-476), played out his brief reign and was deposed. His nemesis, the barbarian general Odovacar, then ruled as patrician and king of Italy (476493) with Ravenna as his seat. There he made his stand when he was defeated by the invading Ostrogothic king, Theodoric: Odovacar used the city as his bargaining chip in a negotiated agreement of joint rule, before he was treacherously murdered.

The regime of Theodoric (493-526) opened a new chapter for Ravenna, in which its importance increased. Rome remained the seat of the old senate, with all the trappings of the Roman past that Theodoric so carefully maintained and respected, but Ravenna was his residence. When Ravenna was confirmed as the Ostrogothic capital, its economic life revived, it became a cultural center, and it saw renewed building projects. Several churches and Theodoric's own famous tomb still testify to his era. However, Theodoric's hope of infusing permanent Germanic leadership into Roman civilization was doomed. Various difficulties, and the murder of his daughter, Amalasuntha, provided an excuse for intervention by the Byzantine empire: its emperor, Justinian (r. 527-565), made the Ostrogothic realm the second target in his ambitious program of reconquest. As imperial commander, the brilliant general Belisarius initiated the era of the Gothic wars, which at first promised a quick victory but turned into a devastating struggle that lasted for two decades. The incompetent Gothic king Theodahad (r. 534-536) was replaced by Witigis (r. 536-540), who fought desperately until he was compelled to surrender Ravenna to Belisarius. The revival of the Goths under Totila (r. 541-553) renewed a conflict that was finally brought to an end by the victories of a new imperial commander, Narses.

Ravenna itself was spared the ruin that most of Italy experienced; largely untouched, it benefited from a campaign of adornment and beautification appropriate to its dignity, and to Justinian's propaganda. Justinian's appointee as prelate of Ravenna, Maximian (r. 546-556), was the first to use the title of archbishop. Narses and his successors maintained the city as the center of restored imperial government and as the bastion of the imperial territories remaining in northern Italy after the Lombards began their own inundation of the peninsula (568). Against their threat, the imperial regime was reorganized, by the later decades of the sixth century, as the exarchate. Ravenna became the capital directly of a province of that name, but its viceregal exarchs also became the governors-general of all of remaining imperial Italy.

Although the Lombards of Spoleto were able to seize Classe in 579 and hold it for ten years, Ravenna itself held firm. Its exarch, Smaragadus, if unable to provide aid to points farther south, at least restored imperial control of the cities along the Via Flaminia. This resecured connection between Ravenna and Rome effectively divided the Lombards' power between the northern kingdom ruled from Pavia and the separate duchies of Benevento and Spoleto. Ravenna seems to have prospered generally through the seventh century, as the economic center of its region. Nevertheless, there were recurrent periods of tumult: to the intermittent Lombard threats were added lurches in Constantinopolitan policies, episodes of local unrest, tension with the papacy in Rome over Ravenna's independence, and the rebelliousness and ambition of some of the exarchs. In 709, Emperor Justinian II (r. 685-695; 705-711), convinced of Ravenna's hostility and disloyalty, sent a force to punish the city: its leading citizens and its bishop were arrested and carried off to Constantinople (the former to be executed, the latter to be blinded), and the city itself was devastated.

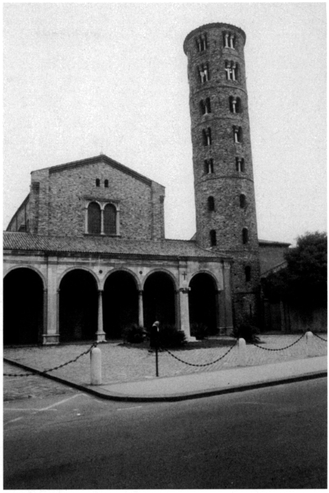

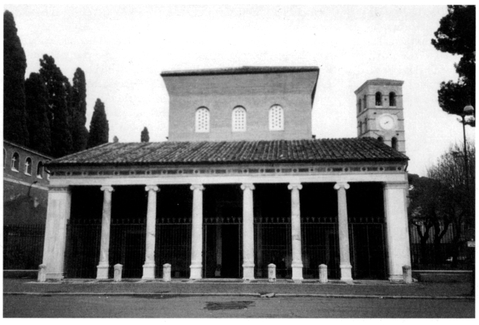

Church of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna. Photograph courtesy of Christopher Kleinhenz.

Ravenna recovered but was racked by new disturbances as the Byzantine government attempted to impose its new religious policies of Iconoclasm over the opposition of the popes in Rome. The sympathies of Ravenna's clergy and population were fully on the side of the popes, and the city only narrowly escaped disaster at the hands of another punitive expedition from Constantinople in 727. But it was the final Lombard threat that signaled Ravenna's fall from greatness. The restless Lombard king Liutprand directed his forces against the city, which received no relief from the Byzantines, and actually seized and held it for a few years (737-740). It was recovered with the help of a fleet from fledgling Venice, but the restored exarchate retained little of its former control over the strained components of Byzantine Italy: the Lombards courted the support of the papacy, against the interests of the Byzantine empire, for control of northern Italy. A new pope, Zacharias (r. 741—752)—the pope who was to initiate a momentous alliance with the Franks—was able in 743 to persuade the aging Liutprand to cease putting pressure on Ravenna. But Liutprand died the following year, and in 751 his successor, Aistulf (r. 744-757), at last achieved the Lombards' aim of seizing Ravenna and ending once and for all its role as a base for Byzantine rule in northern Italy.

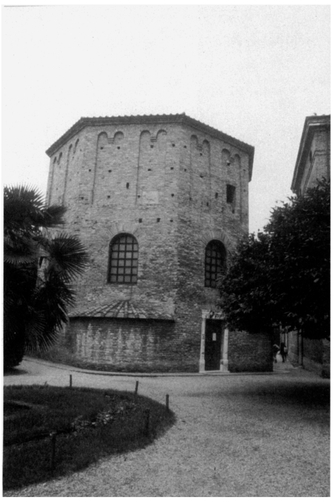

Neonian baptistery, Ravenna. Photograph courtesy of Christopher Kleinhenz.

Ravenna continued to be the administrative and ecclesiastical center for its region under new overlords, but they were not long to be Lombard. The personal appeals of Pope Stephen III (r. 752—757) to the Franks resulted in the Donation of Pepin (754) and the successive campaigns of Pepin the Short (755, 756). Aistulf was defeated, and the new territorial enclave of the papal states was created as a Frankish protectorate. Ravenna and the immediate lands of the old exarchate now became part of that regime, and in 757 the new pope, Paul I, visited Ravenna, to achieve territorial control and complete the subjection to Rome of Ravenna's long-independent archbishopric.

The quarrels of the last Lombard king, Desiderius (r. 757— 774), with Pepin's son, the great Frankish ruler Charlemagne (r. 768-814), resulted in the final destruction of the Lombard monarchy—or rather the annexation of its crown by the Frankish dynasty—and the renewal (774) of the Donation of Pepin. Though Ravenna and its district remained part of the papal patrimony, it was also under temporal control of its Frankish protectors. Charlemagne himself, visiting the city, marveled at its Byzantine splendors and dreamed of emulating them by copying Ravenna's architecture in his palace chapel at Aix-la-Chapelle and by carrying off some of Ravenna's art. In the aftermath of this tumultuous subjection, Ravenna's past glories and its continuing struggle against the papacy found their strongest literary voice in the work of Agnellus Andreas, a cleric who belonged to a prominent family. His Liber pontificalis ecclesiae Rav ennatis, written c. 830-845, though spotty and problematic, remains our most important source for the city's history and life.

Conquest by the Franks and control by the papacy reduced Ravenna, meanwhile, from a capital city to a backwater provincial town. Its decline was accelerated by the decay of its old port facilities and the waning of its commercial activity—to be replaced by the restless enterprise of Venice. Nevertheless, as the Franks' power faded and as the northern papal territories were appropriated into the neo-Lombard "kingdom of Italy" (888-962), immediate ecclesiastical control was exercised anew by Ravenna's archbishops, who were given a freer hand as a result of the papacy's period of decadence. With the reestablishment of German dominion over northern Italy by Otto I (r. 936-973) and his dynasty, the prelates of Ravenna became their enthusiastic supporters. These prelates remained agents first of the Saxon emperors and then of the Franconian successors, holding high positions at court and winning for Ravenna intermittent recognition as the administrative seat of German power in Italy, and for themselves confirmation of their own temporal power in the region.

Ravenna flourished sufficiently in this era to contribute at least three distinguished personages to the religious life of the time. Two were of the local Onesti family: Saint Romuald (born c. 956), educated in the Benedictine house of Classe, became a monastic reformer who founded (1012) the order of the Camaldoli; and Pietro degli Onesti, known as Blessed Peter of Ravenna (II Peccatore, died c. 1119), a local man of great piety, built one of the few important structures in Ravenna of the central Middle Ages, the church of Santa Maria in Porto Fuori. The third was Peter Damian (1007-1072), the great reform thinker and writer in the service of the revitalized papacy.

During the eleventh-century papal reform, Ravenna's archbishops remained staunchly pro-German; and during the investiture controversy, one of them, Archbishop Guibert, was elected as an imperialist antipope, Clement III (1080). Because of this stance, Rome briefly deprived Ravenna of power (1106-1118); and the emergence of communes around the territory permanently deprived its archbishops of temporal authority in most of the towns, though they were able to dominate the aristocratic commune of Ravenna itself and enjoy continuing wealth and prestige. Under these archbishops, Ravenna saw some revival of church building and decoration in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. When Frederick I Barbarossa (r. 1152-1190) attempted to reassert German rule in northern Italy, Ravenna again took the lead in supporting the empire. However, in 1198, with changes in circumstances (including increased regional competition from Venice), Ravenna shifted its loyalty and became a leader of the cities in Romagna and the Marches against Hohenstaufen interests; in the process it became reconciled with the papacy and once again recognized the suzerainty of Rome.

Thereafter, Ravenna's archbishops were pushed into the background as a new circle of powerful aristocratic families emerged, among them the Anastagi, Dusdei, Umbertini, Mai-nardi, and Traversari. Competing for seigneurial power, and specifically for the new office of podestà, they made Ravenna another urban battleground for the pro-imperial and pro-papal factions. At first, the Ghibellines under the Ubertini and Main-ardi were able to dominate the city, but in 1218 the Mainardi shifted their alliance to Pietro Traversari. His son, also named Pietro, became podestà in 1225, converted to the Guelf cause, and supported Pope Innocent IV against Emperor Frederick II. The emperor managed to seize Ravenna and hold it tor eight years (1240-1248), having expelled Pietro. The city was subsequently restored to papal control, and the Traversari reestablished their power. In 1276, the papacy's title to the city, along with the full regions of Romagna and the Marches, was recognized anew and definitively legalized by a decree extorted from a feeble new German emperor, Rudolf of Hapsburg.

Church of San Vitale, Ravenna. Photograph courtesy of Christopher Kleinhenz.

However, this triumph of Rome was theoretical, and reality stood in contrast to it. In 1275, one of the archetypal condottieri, the soldier-adventurer Guido (Minore) da Polenta, achieved sufficient ascendancy to drive out the Traversari and take power as capitano del popolo, a position he held until his death in 1310. In the process, he managed to create one of the first examples of a virtually independent territorial signoria in medieval Italy. His power was bolstered by a strategic alliance with his previous enemies, the Malatesta family, who controlled Rimini. The seal of this alliance was the marriage of his daughter, Francesca, to Malatesta's elder son. Francesca's tragic love affair with her handsome brother-in-law, Paolo, and their murder at her husband's hands became material for one of the most famous passages in Dante's Inferno (Canto 5).

The control of the Polenta family over Ravenna was tightened by Guido Minore's son, Lamberto (r. 1310-1316), who was followed by a nephew, Guido Novello da Polenta. A cultivated man with an appreciation for art and letters, Guido Novello attracted to his court such notables as the artist Giotto and, above all, the poet Dante Alighieri, together with Dante s daughter and two sons. Dante apparently arrived in Ravenna in 1317; he is said to have given lectures and instruction there, while putting the finishing touches on his Comedy. In 1321, Dante went to Venice as ambassador on Guido's behalf; on his way back, he was infected with fever, and he died after reaching Ravenna. The grief-stricken Guido planned a noble tomb for Dante, whose remains (repeatedly solicited by the Florentines, but in vain) rested temporarily at the Franciscan church and were then shifted to a series of sepulchres before being placed in the edifice of 1760 where they still remain.

Guido Novello was soon expelled by a rebellious kinsman and transferred his talents to Bologna, where he was elected capitano del popolo (1322); his hope of returning to Ravenna was never realized. His successor, Ostasio da Polenta, was recognized as vicar by both the German emperor and the pope and ruled with great cruelty from 1321 to 1345. The next Polenta lord, Bernardino (r. 1345-1359), was no less brutal and was briefly overthrown by his brothers. Guido Lucio (r. 1359-1389) ruled better, but he too was overthrown by relatives and was succeeded by his son, another Ostasio (r. 1389—1431). The last of the Polentani, yet another Ostasio (r. 1431-1449), had attained his position (barely) through an alliance with Filippo Maria Sforza of Milan. He was then tricked into visiting Venice, where he found himself deprived of his city and sent off to encloisterment and assassination. From 1449 to 1509, Ravenna was held by its old rival, the Serenissima; thereafter, it returned to papal control, under which it remained with only brief interruptions until its incorporation into the emerging Italian state in 1859.

By the late medieval period, Ravenna had lost all its maritime operations and based its prosperity on its operation of the salt flats at Cervia, from which it supplied this valued commodity to the entire Po valley region as its principal export. Not until the creation of the Canale Corsini in 1739 was Ravenna's access to the sea renewed. In modern times, the discovery of natural gas fields revitalized the economy of the city and its region.

Only scraps of Ravenna's Roman past can be traced. Much still remains of the basically Roman city walls, however, along with elements of the gates: the walls were maintained over the centuries, and an impressive Venetian rocca (fortress) enclave at the northeastern corner represents their continuance in the fifteenth century. A number of Ravenna's earliest churches were totally rebuilt (mainly in the Baroque period): these include, notably, the duomo, also known as the Basilica (or Ecclesia) Ursiana; its original foundation is attributed to Bishop Ursus (either 370-386 or 403-429).

Ravenna does, nevertheless, have the finest constellation of monuments and art of the early Christian era in the Byzantine style. Most of these monuments, as we now have them, date from the sixth century, but four important ones survive from the fifth century, and two are associated with one of the great figures in Ravenna's history, Empress Galla Placidia. One of these two, the church of San Giovanni Evangelista, was originally built to fulfill a vow made when the empress and her two children, the emperor Valentinian III and the princess Honoria, were caught in a terrifying storm while sailing from Constantinople to Ravenna for her restoration there. The large basilican church was ruthlessly rebuilt in Baroque style in 1747; still later, after it had been damaged by bombing in World War II, what was left of the original was extensively reconstructed, so that what is seen today preserves little of the empress's actual foundation.

However, the so-called Mausoleum of Galla Placidia is virtually intact and is Ravenna's earliest jewel. It was built originally as a chapel extending the narthex of her church of the Holy Cross: that church has been effectively eliminated by subsequent rebuildings, leaving isolated this small, cruciform chapel, apparently dedicated to Saint Lawrence. It contains three carved sarcophagi, and they have sometimes been identified with the burials of Honorius, Valentinian III, and Galla Placidia. There are stories that Galla Placidia's seated, mummified body survived here until the sixteenth century. In fact, though, it remains debatable whether the building actually functioned for burials, and it is almost certain that the empress herself was interred in Rome, not here. The giory of this little building is not burials but rather the stunning mosaic decoration (which has received some modern restoration). The central domical vault represents the starry heavens, with zoomorphic symbols of the four evangelists; in the spandrels below are figures of saints. Lunettes in the axial arms show (over the door) Christ (with features of Apollo or Orpheus) as the Good Shepherd tending his flock, and (opposite) Saint Lawrence with the fiery grill of his martyrdom and a display of the four Gospel books (though this representation has also been described as the mature Christ burning books of the heretical Arians). The lunettes of the longitudinal arms have animal scenes (doves at fountains; and souls, represented as stags, thirsting after eternal water). The four arm vaults display stars, and the borders are rich in the vegetational collages so beloved of Roman mosaicists.

Another fifth-century monument is the octagonal baptistery that is part of the latter-day cathedral complex. This baptistery is said to have been originally a chamber of the Roman baths; a few fragments of Roman sculpture are to be found in the exterior walls. It is known as the Orthodox or Neonian baptistery (the latter name from its decorator, Archbishop Neon, who served c. 449-459). Its walls are encrusted with arcading and rich marble and stucco revetments, above which are two circles of mosaics: the first showing eight shrines in separate panels, containing either enthroned crosses or altars with open Gospel books; the second showing the twelve apostles carrying their crowns. In the center is one of the earliest representations (much restored) of Christ's baptism, attended by the river-god Jordan.

The last of the monuments of this period is of uncertain date. This is a small chapel dedicated to Saint Andrew, part of the fragments of the medieval archbishops' palace incorporated within later rebuildings (and now part of the Archiepiscopal Museum). Some traditions trace its building back to the bishop and saint Peter Chrysologus (c. 432-450); others date it to Bishop Peter II at the end of the fifth century; and the mosaics are sometimes dated to the time of Archbishop Maximianus (546-556). These mosaics, much reworked, include handsome figural and symbolic elements in the vaulting over an elegant pavement. Even more impressive is the antechamber, which has vaulting with rich naturalistic decoration, framing a panel over the door showing a beardless Christ in full armor (symbolizing the church militant), treading down the lion and the adder and holding an open book revealing the motto Ego sum via Veritas et vita ("I am the way of truth and life").

Several structures survive from Theodoric's ambitious building program; most of these were recast under the imperial restoration, though at least two have come down to us with something of their original character. The great church of Santo Spirito, built for the Arian Christian rites of the Ostrogoths, has been totally lost in rebuildings of later centuries. But near it is the so-called Arian baptistery, which may have functioned earlier as a bath chamber. This small brick octagon is devoid of interior decoration—except at the crown, where there is another mosaic of the baptism of Christ (here too with the river-god Jordan), surrounded by a circle of apostles: Peter holds his keys, Paul holds a book, and the rest hold crowns.

The other original Ostrogothic building is the extraordinary Mausoleum of Theodoric, just outside the northeast corner of the city walls. It is built of finely dressed and squared stone and has two stories: the lower decagonal, the upper circular, surmounted by an enormous monolithic capstone said to weigh some 300 tons. It was presumably originally surrounded by a colonnade of some sort, now lost, which would have included stairs to the otherwise inaccessible upper chamber. Its curious design has given rise to much debate and dispute regarding derivation (Roman or Germanic?) and symbolism (a tent? a helmet? a crown?). The upper chamber still contains a porphyry receptacle, presumably the king's sarcophagus; however, Theodoric's body was desecrated and removed at some point well before the ninth century, when the building was used as a church (Santa Maria della Rotunda) by an adjacent Benedictine monastery.

A principal monument begun by Theodoric but transformed under the imperial restoration is one of Ravenna's greatest churches, known now as Sant'Apollinare Nuovo. Its Arian builder originally dedicated it to Christ; when it was converted officially to the Catholic rite by the archbishop and saint Agnellus in 560, it was rededicated to Saint Martin (though it was also known as the Caelum Aureum from its onetime golden roofing); it received its final consecration—to Ravenna's traditional first bishop, Apollinaris—in the ninth century; the word Nuovo distinguishes it from the great church of Apollinaris in Classe. The cylindrical campanile also dates from the ninth century. The present portico and facade date from the sixteenth century, when the decaying church was overhauled.

The interior of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo is in basilican form, with a wide central nave and two side aisles. Whatever decoration was made around the apse has been lost, first in an earthquake of the sixth century and then during further replacements in the eighteenth, (The interior west wall is likewise bare, though now affixed to it is a mosaic fragment showing a crowned royal portrait decorated and labeled as Justinian, but perhaps originally Theodoric.) However, what does remain—the mosaic decoration of the nave—is spectacular in size and quality. In the lowest mosaic register on either side, directly above the (rebuilt) arches of the colonnade, are processions of saints. The procession on the southern side emerges from a representation (at the west end) of Ravenna, dominated by the portico and ceremonial portal of Theodoric's palace, but with some of the city's churches visible in the background. The twenty-five saints are all male—each identified in lettering—holding palms and martyrs' crowns. The procession concludes (at the east or altar end) at a great throne, where Christ sits in majesty, surrounded by four angelic sentinels. On the northern side is a procession of female saints— twenty-one virgin martyrs; these too are identified by name labels and are holding palms and crowns. They emerge from a representation at the west end showing Classis, through the gate of its walls, behind which are ships in the harbor. At the head of this female procession we find the three Magi (with name labels), carrying their gifts before the star of Bethlehem, as they reach the common destination at the east end, showing another throne on which sits a majestic Madonna holding the baby Jesus, while another four angels stand guard. In the register above on both sides, alternating with windows, are figures of prophets and church fathers, sixteen on each side. Above them, in bands that run the full length of each side, are mosaic compartments. Those over the heads of the figures show ceremonial throne-shrines. Alternating with them, and over the windows, are scenes, thirteen on each side, showing episodes from the life of Christ. Those on the north side, over the female saints, show miracles performed by Christ; those on the south side, over the male saints, show episodes from Christ's passion and resurrection. These magnificent mosaics were begun under the Ostro gothic regime but were modified in mid-century after the Byzantine conquest. Revisions are particularly evident in the scene of Theodoric's palace, where certain figures were eliminated from the king's retinue.

Three important churches, of which two survive, were built directly by the Justinianic regime, with considerable financial contributions from a local official, Julianus Argentarius. The church that was lost was San Michele in Africisco (whose apse, greatly restored, was transferred to Berlin for display during the nineteenth century). One of the surviving churches is the remarkable San Vitale, begun under Bishop Ecclesius (522-532) and dedicated in 547 by Archbishop Maximian. It is octagonal in shape, and its dome is supported by eight piers in two stories linked by columned galleries. San Vitale has been linked to architectural experiments in Constantinople during Justinian's time, and its pattern was the model for Charlemagne's palace chape! (to which were transferred some decorations stripped from San Vitale). The original mosaic decoration survives only in the spectacular chancel. Under a richly decorated arch—focused on a medallion of the Lamb, arch medallions of Christ and the apostles, and scenes of Jerusalem and Bethlehem—the apse conch shows Christ triumphantly enthroned, with Saint Vitalis (to whom Christ offers a crown) and Bishop Ecclesius (holding a model of the church, as its donor) presented to him by attending archangels. On either side above the altar, symbols and figures of the evangelists frame Old Testament scenes prefiguring the eucharist: the sacrifices of Abel and Melchisidech, and Abraham's serving of the three angels and his sacrifice of Isaac. The most famous works are two panels on either side of the apse wall, showing Justinian and Theodora as contributors to the church. Backed by guards and retinue, Justinian appears in court regalia, as if in a procession, carrying a gold basin, to be received by Archbishop Maximian (whose name is explicitly given) and others (whom some scholars have tried to identify with Belisarius and Julianus). Theodora is shown in a side chamber with eunuchs and handmaids, near a fountain, carrying her gift, a chalice; her rich garb includes a representation of the three Magi.

The second of the surviving Justinian churches is Sant'Apollinare in Classe. This massive basilican structure—built, it is said, at the site of Saint Apollinaris's grave—was begun by Bishop Ursicinus (532-536) and consecrated by Archbishop Maximian (549). The marble decorations of the nave and aisles were removed as plunder by Sigismondo Malatesta in 1449. The surviving, glorious mosaic decorations are all in the apse. Below a medallion of Christ and the symbols of the evangelists and portrayals of the Christian flocks coming forth from Jerusalem and Bethlehem, the apse conch evokes the Transfiguration, symbolized as an enormous cross mounted within a star-studded circle; it is attended on the sides by Moses and Elijah, and it dominates a paradisiacal landscape full of vegetation and populated by a flock of twelve sheep (representing the apostles). Above, the hand of God gives a blessing; below, centrally placed, is Saint Apollinaris in prayer. Between the windows are portraits of prelates of Ravenna. On the right side wall, clearly in imitation of the Justinian panel in San Vitale, the emperor Constantine IV (r. 668-685) is shown with two of his sons and attendants awarding privilegia (a large rolled document, so labeled, authorizing the see's autocephalous or independent status) to Archbishop Repa-ratus. This mosaic, though in a debased and cruder style, is the latest of the great Byzantine masterpieces in this medium in Ravenna.

A superlative work from the Justinianic era is displayed in the Archiepiscopal Museum: this is the throne of Maximianus, made in Constantinople as a gift from Justinian to Achbishop Maximianus. Over a wooden frame are mounted a network of ivory panels, showing Christian saints, the Old Testament story of Joseph, and miracles of Christ.

The latest monument of Ravenna's early medieval era is a facade wall to be seen not far from the church of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo, It was traditionally misidentified with the palace of Theodoric, but it is apparently the front portion (later used as a church) of the palace of the Byzantine exarchs. Excavations behind it have revealed portions of the foundations.

See also Alaric the Visigoth; Belisarius; Benevento; Byzantine Empire; Camaldoli; Charlemagne; Condottieri; Dante Alighieri; Desiderius; Exarchate of Ravenna; Frederick I Barbarossa; Frederick II Hohenstaufen; Galla Placidia; Gothic Wars; Guido Novello da Polenta; Honorius, Emperor; Innocent IV, Pope; Investiture Controversy; Justinian I; Liut prand; Lombards; Milan; Mosaic; Narses; Odovacar; Pepin III the Short; Romuald of Ravenna, Saint; Spoleto; Stephen II, Pope; Stilicho; Theodora; Theodoric; Totila; Venice; Witigis; Zacharias, Pope

JOHN W. BARKER

Agnellus. Liber pontificalis ecclesiae Ravennatis, ed. O. Hodder-Egger. In Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Scriptores Rerum Langobardicarum et Icalicarum Saec. VI IX. Hannover, 1878, pp. 265-391. (See also partial version in A. Testi Rasponi, ed. Rerum Italicarum scriptores, 2(3). Bologna, 1924.)

Bovini, Giuseppe. Ravenna Mosaics: The So-Called Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, the Baptistery of the Cathedral, the Archiepiscopal Chapel, the Baptistery of the Arians, the Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo, the Church of San Vitale, the Basilica of Sant'Apollinare in Classe, trans. Giustina Scaglia. Greenwich, Conn.: New York Graphic Society, 1956.

Capeti, Sandro. Mosaici di Ravenna. Ravenna: Edizioni Salera, n.d.

Deichmann, Friedrich W, Ravenna, Hauptstadt des sp'dtantiken Abendlandes, 3 vols, (in 5). Wiesbaden: Steiner, 1969-1989.

Hodgkin, Thomas. Italy and Her Invaders, 376-814, 8 vols. Oxford: Clarendon, 1880-1889. (Reprint, New York: Russell and Russell, 1967.)

Hutton, Edward. The Story of Ravenna. London: Dent, 1926.

Martinez Pizarro, Joaquin. Writing Ravenna: A Narrative Performance in the Ninth Century. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1996.

Paolucci, Antonio. Ravenna: An Art Guide. Ravenna: Edizioni Scala, 1971.

Simson, Otto G. von. Sacred Fortress: Byzantine Art and Statecraft in Ravenna. Chicago, Ill.: University of Chicago Press, 1948. (Reprint, 1976.)

Rayniero (d. 1358) belonged to a prominent pro-imperial family in Forli and spent much of his youth in exile. He then lived in Ravenna but studied in Bologna with Bertoluccio Preti. Rayniero taught in Bologna from 1319 until 1324; he taught the Infortiatum and Digestum vetus, leaving the Digestion novum and the Code to his colleague Giacomo Bottrigari. Ricciardo Malombra was another colleague. During an interdict imposed on the city in 1338, Rayniero left for Pisa. Then he moved to Padua, where he lectured until his death. Rayniero left annotations to various passages in the Digest and the Code, plus a few brief works and legal opinions. The great Bartolo da Sassoferrato studied with Rayniero and Bottrigari.

THOMAS M. IZBICKI

Clarence Smith, J. A. Medieval Law Teachers and Writers Civilian and Canonist. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 1975.

Re Giovanni (Jean de Brienne, c. 1180-1237) was born in France and spent several years in Italy. From the end of the First Crusade until his death, he participated in numerous military ventures; the chronicler Salimbene praises him for his physical attributes and his military prowess. Re Giovanni acquired the title of king of Jerusalem through his marriage to the daughter of Corrado di Monferrato. His own daughter Isabella married Frederick II in 1225, and Re Giovanni probably spent some time at the magna curia, where he familiarized himself with the Sicilian poetic language. The Vatican Codex (Lat. 3793) attributes one poem to him, but his authorship has been called into question by some scholars. Lazzeri (1942) assumes that this poem, a rare example of the discordo genre, may have originally been written in French and then translated by Re Giovanni. Three French poems attributed to Re Giovanni were actually written by Jehan de Braine, count of Macon and Vienne, who died in the Holy Land in 1239.

See also Italian Prosody; Scuola Poetica Siciliana

FREDE JENSEN

Lazzeri, Gerolamo. Antologia dei primi secoli della letteratura italiana. Milan: Hoepli, 1942, pp. 496-501.

Monad, Ernesto. Crestomazia italiana deiprimi secoli, rev. ed., ed. Felice Arese. Rome, Naples, and Città di Castello: Società Ed. Dante Alighieri, 1955, pp. 102-104.

Torraca, Francesco. Studi su la lirica italiana del Duecento. Bologna: Zanichelli, 1902, pp. 92-93.

See Normans

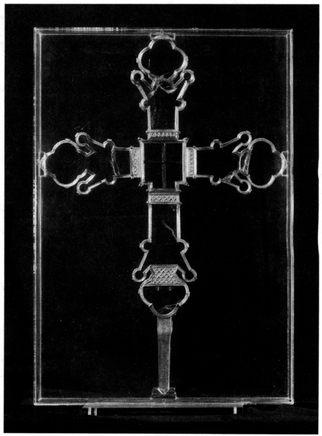

Reliquaries serve as containers of sacred Christian relics dating from the earliest cult of the martyrs. Relics are objects identified with the life of Christ or with parts of the bodies of martyrs— people who died for their religious beliefs. Reliquaries fall under a variety of types: shrines, caskets, coffers, reliquaries, tabernacles, or diptychs and triptychs.

Among the earliest containers of saints' relics, small openings were cut into the receptacle, usually a small box, for oils to be extracted for distribution among the faithful. The earliest reliquaries date from the fifth century and have decorated covers of precious metals. They include early Christian caskets (coffers), such as the ivory Lipsanotheca of Brescia; a fifth-century gold cylinder from beneath the altar of the cathedral of Puli; and another gold cylinder from the cathedral of Grado. Similar small boxes, called staurothekes, are found in the Byzantine empire and subsequently in the west and usually contain a small cross inside of which was a relic believed to come from the actual cross of the crucifixion. The cross of Urban II (1092), preserved in the reliquary chapel of Badia della Trinità della Cava (monastery of Cava dei Tirreni, Salerno), contains such a relic.

During the Romanesque period, and corresponding to the crusades to Jerusalem, there was another surge of activity, during which relics of the saints and holy sites were brought back. Reliquaries in the form of body parts of saints—such as the arm reliquary (brachium) of Saint Magnus or the leg reliquary of Saint Theodore (Venice, Treasury of San Marco)—are similar to those found throughout the rest of the European continent. During the age of pilgrimage (c. 1100-1300) pilgrims traveled long distances to visit shrines where sacred relics were preserved. Often these pilgrims were suffering from incurable illnesses, or they were criminals sentenced by episcopal courts to make penitential pilgrimages. Their travel to distant lands thus became a Journey for spiritual, if not physical, healing, or a way of repenting for their sins and crimes. There was a strong traditional inclination toward sympathetic magic; thus proximity to sacred relics was believed to increase the likelihood of a cure or spiritual cleansing. Some reliquaries were placed where they could be touched or kissed by the devout. Whereas monumental settings are found at major sites in France (e.g., Saint Foi at Conques, Saint Sernin at Toulouse) and in Spain (e.g., Santiago de Compostela), reliquaries in Italy did not take on monumental form until the Gothic era, when they followed models in France, Spain, and Germany. One example is a casket reliquary of unknown origin in the treasury of Pope Boniface VIII (c. 1305) in the cathedral of Anagni.

Relics represent a wide range of objects: clothing, ornaments, bodily remains of saints, images, oil from the lamps at holy sites, and soil from sacred places. Other relics are identified with events in the life of Christ or of a saint. Relics include the wood believed to be from the True Cross, thorns believed to be from Christ's crown of thorns, the arms of Saint Blaise and Saint Magnus (in Venice), a finger of Saint Louis (in Bologna), and the foot of the tenth-century Saint Egbert (in Cologne). A monstrance or ostensorium held relics; monstrances, unlike other reliquaries, were sometimes carried in processions. Head reliquaries, usually in the round, were made of gold or silver, or a combination of metals; although most date from the Romanesque era, they continue to be found in the late fourteenth century. Among the reliquaries of medieval saints are those of Praxede (inscribed Pope Honorius III, 1216-1227) and Agnes (Nicholas III, 1277-1280), both in the Vatican Museum; and a late thirteenth-century head reliquary of Saint Galganus in Siena (in the cathedral museum), made for the abbey of San Galgano (near Siena). The reliquary of Saint Juliana (1376) is Umbrian in origin, and the finger reliquary of Saint Louis of Toulouse in the church of San Domenico (Bologna) was made in Italy by French artists for Charles II of Anjou. A whole bust reliquary of French origin of Saint Januarius (c. 1304-1306) is preserved in the treasury of the cathedral in Naples. A reliquary bust of Saint Agata was made for the cathedral of Catania (1376) by Giovanni di Bartolo; a silver reliquary for Saint Zenobius by Andrea Arditi survives in the cathedral in Florence (it is dated 1331). A Tuscan reliquary bust of Saint Donatus (dated 1346, by "Pietro and Paolo"):an be found in the Pieve di Santa Maria (Arezzo); another bust af this saint is found in the northern Italian town of Cividale [it is in the cathedral treasury and is signed by Donandino). Reliquary busts (now lost) of saints Peter and Paul, made for [he cathedral of Catania (1376) by Giovanni di Bartolo, were donated by Pope Urban V to Saint John Lateran. These examples attest to the proliferation of both the images and the religious practices surrounding them.

Celebration of relics of saints became widespread by the mid-thirteenth century. This is indicated by the large number of altars dedicated to a large number of saints, and by the emergence of pilgrimages to these locations. At this time, the containers for the relics began to assume monumental form. By the tenth century, portable altars usually contained relics, as did later small portable altarpieces, both of which were commonplace in the late Middle Ages. The container holding the remains of a saint is, significantly, called a casket. Caskets had the form of a rectangular box with a base and a pedimented lid; and by the late eleventh century they were often covered with fine metalwork and enamel. The casket, or châsse, with a gabled roof and finials became a common form at the beginning of the Gothic period, but it was not limited to the shape of a casket. After Saint Louis purchased the "crown of thorns" from Baldwin II, the Latin emperor of Constantinople (1239), it was made into a reliquary crown (c. 1264). Saint Louis was himself canonized in 1297, after establishing the feast of Corpus Christi. His own body was then put into reliquaries, some as small as liturgical crosses and glass monstrances. As macabre as these practices may seem today, such relics were required to establish the validity and efficacy of any Christian altar. In each church, the main altar and all subaltars were required to hold the relics of a sacred event, site, or saint.

Reliquary with a splinter of the Holy Cross. Anonymous, fourteenth century. Santa Croce, Florence. Photo: © Scala/Art Resource, N.Y.

Relics were sometimes incorporated into diptychs and triptychs, because this made them more portable from altar to altar—unlike the large shrines established during the Romanesque period. Diptychs and triptychs do not appear in Italy until the fourteenth century, when smaller devotional images were more commonplace than they had been in earlier times. A notable example of this kind of monument is the beautiful enamel reliquary of the Holy Corporal by Ugolino di Vieri (1337-1338) in the cathedral of Orvieto. This tabernacle reliquary was a collaborative effort of three artists in Orvieto— Ugolino (a Sienese), Viva di Lando, and Bartolommeo di Tommè(also known as Pizzino)—to commemorate the "miracle of Bolsena." It is designed in the form of a triptych in three registers; both sides of the panels present historiated scenes (from the life of Christ), terminating with gables at the top. This design creates an image similar to that of the cathedral facade, and to the Maestà by Duccio di Buoninsegna that once graced the high altar of the cathedral in Siena.

Other reliquary monuments also celebrate sacred objects: e.g., the reliquary of the Tree of the Cross, dating from c. 1360, in Lucignano (Museo Civico) in the Val di Chiana in Tuscany; the crozier in the cathedral treasury at Citta di Castello (Umbria); the reliquary of the Holy Thorn in San Lorenzo (Florence); and the reliquary of the Precious Blood (now at Montreuil-surMer, France, but Italian in origin).

Other Gothic shrines include the reliquary of Saint Chrysogonus (1326, in the treasury of the cathedral of Zara); the reliquary bust of Saint Ermagora (in the cathedral of Gori-zia); the reliquary of San Giovanni Gualberto, at the Vallombro-san monastery of Passignano; the shrine of Saint Simeon by Francesco da Sesto of Milan (1377—1380); and a shrine at Zara in the church of Saint Simeon.

Throughout the Middle Ages, the worship of reliquary objects was widespread and was often associated with miracles and miraculous cures. The fashioning of reliquaries and their placement on altars in medieval chapels and churches responded to an ancient human quest for healing and spiritual peace.

See also Ivory

DARRELL D. DAVISSON

Arnold, Steven. Reliquaries. Pasadena, Calif.: Twelvetree, 1984.

Braun, Joseph. Der christliche Altar in seiner geschichtlichen Entwicklung. Munich: Alte Meister Guenther Koch, 1924.

—. Die Reliquiare des christlichen Kultes und ihre Entwicklung. Freiburg im Breisgau: Herder, 1940.

Durandus, William. The Symbolism of Churches and Church Ornaments: A Translation of the First Book of the Rationale divinorum officiorum, trans. John Mason Neale and Benjamin Webb. London: Gibbings, 1906. (Reprint, New York: AMS, 1973.)

Heckscher, William S. "Relics of Pagan Antiquity in Medieval Settings." Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 1, 1937-1938, pp. 204-220.

Lasko, Peter. Ars Sacra, 800-1200. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972.

McCracken, Ursula. Liturgical Objects in the Walters Art Gallery. Baltimore, Md.: Walters Art Gallery, 1967.

Os, Henk W. van. The Art of Devotion in the Late Middle Ages in Europe 1300-1500, trans. Michael Hoyle. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1994.

—. The Way to Heaven: Relic Veneration in the Middle Ages. Baarn: De Prom, 2000.

Sicari, Giovanni. Reliquie insigni e "corpi santi" a Roma. Rome: Alma Roma, 1998.

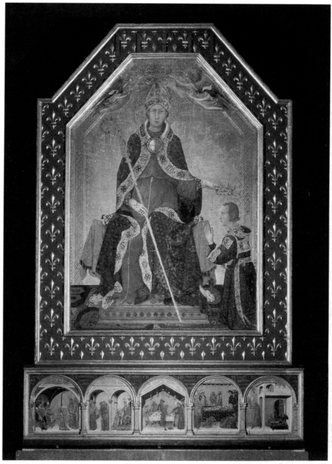

The Dominican Remigio dei Girolami (d. 1319) was a well-known teacher and preacher in Florence. He was a member of a family prominent in the wool guild and in municipal civic life. For many years, he was lector of theology in the great Dominican convent of Santa Maria Novella. In addition to his fame as a preacher, he also gained renown as a welcomer of visiting kings, cardinals, and other dignitaries; as an exhorter of civic officials to promote the common good; and as an orator at funerals and commemorative occasions for local and foreign notables. There were few types of public ceremony in Florence or in his order in which he was not at least occasionally a conspicuous participant. Although some of his closest relatives were exiled after the triumph of the Black Guelf faction in 1302, Remigio's own popularity with those in power seems to have continued. In 1313, answering a query from Sienese officials about his political soundness, the Florentine government called him "a leading father to our corporation (universitati)."

Remigio also wrote treatises on a rich variety of theological, philosophical, and political subjects, but these seem to have aroused little interest until the second half of the twentieth century, when a number of them were edited. Early in the century, G, Salvadori published some extracts from Remigio's public sermons and advanced the thesis that he must have been Dante's teacher at the time when Dante tells us he was frequenting the "schools of the religious." The theory remains unproved, but it has been widely accepted and is not improbable, for during this period Remigio was the principal lector of one of the two leading schools of the religious in Florence.

Whether he taught Dante or not, Remigics's teaching was important in the Florence of his own day, and it was most emphasized by the chronicle or necrology of his own convent. The entry about Remigio says that at the time of his death he had been a Dominican for fifty-one years and ten months, of which more than forty years had been spent as lector of Santa Maria Novella. Remigio was licensed in arts in Paris, entered the Dominican Order in the "first flower of his youth," and made such rapid progress, according to the necrology, that he became lector at Florence while still a deacon and before being ordained as a priest. He must have become a Dominican in Paris c. 1267-1268, since, as Panella (1982) has shown, he heard Saint Thomas Aquinas during Aquinas's last period of teaching there, from 1269 to 1272. Remigio served in many important positions in his order, and he was already preacher-general by 1281. He returned to Paris c. 1298 at the express wish of his convent to continue his theological studies and qualify for the magisterium. He had returned to Florence in August 1301 but soon went to Rome in the hope of receiving the magisterium from Pope Boniface VIII, but this ambition was frustrated by Boniface's sudden death. Remigio finally received the magisterium from a fellow Dominican, Pope Benedict XI, probably in 1304 at Perugia; we know that he preached and disputed there, and apparently he did not return to Florence again until 1306 or 1307. This seems to have been his last long absence from the city and the lectorate of Santa Maria Novella, though the necrology says that he gave up teaching and preaching a few years before his death (probably by 1316, when there was a new lector of theology at the convent) and devoted himself to composing and compiling religious books. This activity seems to have consisted in large part in the collecting and editing of his own works.

Remigio's works are contained in tour early fourteenth-century double-columned folio volumes and a later collection of Lenten sermons in the Conventi soppressi manuscript collection of the National Library of Florence, plus two copies of a commentary on the Song of Songs in the Laurentian Library, also in Florence. The four Conventi soppressi volumes are C.4.940, Remigio's treatises; D.1.937, sermons desanctis et festis; G.3.465, questions; and G.4.936, sermons de tempore, and those for special occasions. The last includes a section of prologues that Remigio preached at the beginning of his courses. Most are on books of Peter Lombard's Sentences or the Bible; but two deal with Aristotle, and one of these is devoted specifically to Aristotle's Ethics. Together they comprise some 2,700 folio sides. The four folio volumes, except for the first seventy-four leaves of C.4.940, are all written in the same highly abbreviated hand, with additions, annotations, and corrections by a second hand, evidently that of Remigio himself. Although a few copies of particular sermons have been found in manuscripts of non-Florentine provenance, Remigio's fame was mainly local, and knowledge of his writings was confined almost entirely to his own convent. But his writings must have been important there, for they furnished a rich repository of materials for preaching and for instruction in an important, if somewhat provincial, Dominican school. The purpose of the compilation of these volumes is confirmed by an elaborate web of cross-references, both in the text and in the margins, that connect works in the same volume and in different volumes. Many of the sermons, for example, are merely outlines but often contain references to allegorical and anecdotal material in other sermons and in treatises. As for the treatises (contained in Biblioteca Nazionale, Florence, MS Conventi Soppressi C.4.940), they do not cite the sermons, but they often cite and thereby reinforce each other.

Originality is not the most striking characteristic of Remigio's works. On the other hand, his concern with contemporary events and problems and his intense Florentine patriotism are often apparent. Although Remigio copied quantities of material from Aquinas in his treatise De peccato usure, its editor describes Remigio's analysis of the sin of usury as somewhat more flexible than Aquinas's. In a long digression in another treatise, Contra falsos ecclesie professores, Remigio tried valiantly, if with only parrial success, to find a middle ground between those who exalted and those who decried the claim of the papacy to universal temporal authority. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of Remigio's thought was his effort to fuse the Augustinian concept of peace with the Aristotelian concept of the common good and apply them to the problem of faction in his own city, identifying them with the good of the commune. Several of his treatises and a number of his sermons are devoted to this theme. He also—like his fellow Dominican Ptolemy of Lucca—tried to inspire his fellow citizens through examples of civic virtue furnished by the heroes of the Roman republic, whose willingness to sacrifice themselves for their patria he (again like Ptolemy) did not hesitate to identify with the Christian virtue of caritas. Not to be a citizen, he affirmed with Aristotle, was not to be a man; and for Remigio, citizenship required the realization that the good of the part was subordinated to and included in the good of the whole. Of course, the common good of Christendom took precedence over the common good of Florence, and its head should be obeyed whenever possible; but if a command of the pope contravened the peace and well-being of the commune, even that command should be disregarded.

See also Dante Alighieri; Ptolemy of Lucca; Thomas Aquinas, Saint

Contra falsos ecclesie professores (fols. 154v-196v), ed. Filippo Tamburini. Rome, 1981.

De bono comuni (fols. 97r-106r), ed. M. C. De Matteis. In La "teologia politica comunale" de Remigio de' Girolami. Bologna, 1977 (text: 1-51).

De bono cornuni (fols. 97r-106r), ed. Emilio Panella. In "Dal bene comune al bene del comune: I trattati politici di Remigio dei Girolami nella Firenze dei Bianchi-Neri." Memorie Domenicane, 16, 1985, 1-198. (Text, pp. 123-168.)

De bono pads (fols. 106v-109r), ed. Charles T. Davis. In "Remigio de' Girolami and Dante: A Comparison of Their Conceptions of Peace." Studi Danteschi, 36, 1959, pp. 105-136. (Text, pp. 123— 136. See also editions by M. C. De Matteis, in La teologia . . ., text, pp. 53-71; and Emilio Panella, in "Dal bene comune ....," text, pp. 169-183.)

De contrarietate peccati (fols. 124v-130v).

De iustitia (fols. 206r-207r), ed. Ovidio Capitani. In "L'incompiuto Tractatus de iuscitia' di fra Remigio de' Girolami." Bullettino dell'Istituto Storico Italiano per il Medio Evo, 11, 1960, pp. 91-134. (Text, pp. 125-128.)

De misericordia (fols. 197r-206r), ed. A. Samaritani, in "La misericordia in Remigio de' Girolami e in Dante nel passaggio tra la teologia patristico-monastica e la scolastica." Analecta Pomposiana, 2, 1966, pp. 169-207. (Text, pp. 181—207.) De mixtione elementorum inmixto (fols. llv-17r).

De modis rerum (fols. 17v—70v). (Earlier version with Remigio's corrections in MS Conventi Soppressi E.7.938.)

De mutabilitate et inmutabilitate (fols. 131r-135v).

De peccato usure (fols. 109r-124v), ed. Ovidio Capitani. In "II 'De peccato usure' di Remigio de' Girolami." Studi Medievali, 6(2), 1965, pp. 537-662. (Text, pp. 611-660.)

Determinatio de uno esse in Christo (fols. 7r-llv), ed. Martin Grabmann. In Miscellania Tomista. Estudis Franciscans, 24. Barcelona, October-December 1924, pp. 257-277.

Determinatio utrum sit licitum vendere mercationes ad terminum (fols. 130v-131r), ed. O. Capitani. In "La 'venditio ad terminum' nella valutazione morale di S. Tommaso d'Aquino e di Remigio de' Girolami." Bullettino deU'Istituto Storico Italiano per il Medio Evo, 70, 1958, pp. 299-363. (Text, pp. 343-345.)

De via paradisi (fols. 207r-352v).

Divisio scientie (fols. lr-7r), ed. Emilio Panella. In "Un'introduzione alia filosofia in uno 'studium' dei Frati Predicatori del XIII secolo. 'Divisio scientie' di Remigio dei Girolami." Memorie Domenicane, n.s., 12, 1981, pp. 27-126. (Text, pp. 81-119.)

Questio de subiecto theologie (fols. 91r-95v), ed. Emilio Panella. In Il "De subiecto theologie" (1297—1299) di Remigio dei Girolami. Rome, 1982. (Text, pp. 4-71.)

Quodlibetum primum (fols. 71r-81v) and Ouodlibetum secundum (fols. 81v-90v), ed. Emilio Panella. In "I quodlibeti di Remigio." Memorie Domenicane, 14, 1983, pp. 1-149. (Text, pp. 66-146.) Speculum (fols. 135v-154v).

Extractio ordinata per alphabetum de questionibus tractatis. Biblioteca Nazionale, Florence, MS Conventi Soppressi G 3.465. (See Questio de duratione monitionum capitubrum Generalium et Provincialium, ed. Emilio Panella. In "Dibattito sulla durata legale delle 'Admonitiones,' " pp. 85-101; text, pp. 97-101. See also table of contents at the end of the manuscript, ed. J. D. Caviglioli and R. Imbach. In "Brève notice sur Extractio ordinata per alphabetum de Remi," Archivum Fratrum Praedicatorum, 49, 1979, pp. 105-131; text, pp. 115-131.)

Postille super Cantica Canticorum. Biblioteca Laurenziana, Florence, MSS Conventi Soppressi 362 (fols. 88r-123r; 516, fols. 221r-266v). (The latter MS contains also Distinctiones for the letter A, fols. 266v-268v, ed. Emilio Panella. In "Per lo studio di fra' Remigio dei Girolami." Memorie Domenicane, n.s., 10, 1979, pp. 271-283.)

Sermones de diversis materiis. Biblioteca Nazionale, Florence, MS Conventi Soppressi G.4.936, fols. 247r-404v. (See scraps from these sermons, as well as Versus and Ritbmi placed by Remigio at the end of the codex, ed. G. Salvadori and V. Federici. "I Sermoni d'occasione, le sequenze e i ritmi di Remigio Girolami fiorentino." In Scritti pari di filologia a Ernesto Monaci, 455-508. Rome: Forzani, 1901. See also the sermons De pace, ed. Emilio Panella. In "Dal bene comune . . pp. 187-198. This section of MS Conv. Soppr. G.4.936 also contains prologues to courses on books of the Bible, Sentences, and Aristotle's Ethics, fols. 276v-345r. See Emilio Panella, ed. Prologus in fine sententiarum. In Il "De subiecto theologie," pp. 73-75. See also Emilio Panella, ed. Prologus super librum Ethicorum. In "Un'introduzione alla filosofia," pp. 122-124.)

Sermones de quadragesima. Biblioteca Nazionale, Florence, MS Conventi Soppressi G.7.939.

Sermones de sanctis et de festis. Biblioteca Nazionale, Florence, MS Conventi Soppressi D.1.937.

Sermones de tempore. Biblioteca Nazionale, Florence, MS Conventi Soppressi G.4.936, fols. lr—246v.

Davis, Charles T. "An Early Florentine Politica! T heorist: Fra Remigio de' Girolami," Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 104, 1960, pp. 662-676. (Reprinted in Dante's Italy and Other Essays. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1984, pp. 198-223.)

Egenter, R. "Gemeinnutz vor Eigennutz: Die soziale Leitidee im Tractatus de bono communi des Fr. Remigius von Florenz." Scholastik, 9, 1934, pp. 79-92.

Grabmann, Martin. "Die Wege von Thomas von Aquin zu Dante." Deutsches Dante Jahrbuch, 9, 1925, pp. 1-35.

Maccarrone, Michele. " 'Potestas directa' e 'potestas indirecta' nei teologi del XII e XIII secolo." Miscellanea historiae pontificiae, 18, 1954, pp. 27-47.

Minio-Paluello, Lorenzo. "Remigio Girolami's De bono communi."' Italian Studies, 2, 1956, pp. 56-71.

Orlandi, Stefano. Necrologio di S. Maria Novella, 2 vols. Florence: Olschki, 1955, Vol. 1, pp. 35-36, 276-307.

Panelia, Emilio. "Per lo studio di fra Remigio dei Girolami (†1319)." Memorie Domenicane, n.s., 10, 1979.

—. "Il repertorio dello Schneyer e i sermonari di Remigio dei Girolami." Memorie Domenicane, n.s., 11, 1980, pp. 632-650.

—. "Remigiana: note biografiche e filologiche." Memorie Domenicane, n.s., 13, 1982, pp. 366-421.

—. "Nuova Cronologia Remigiana." Archivum Fratrum Praedicatorum, 60, 1990, pp. 145-311.

Pugh Rupp, T. "Ordo caritatis: The Political Thought of Remigio dei Girolami." Dissertation, Cornell University, 1988. (Ann Arbor Microfilms.)

"Remigio Dei Girolami." Dictionnaire de spiritualité, 13, 1987, pp. 343-347.

Schneyer, Johannes Baptist. Repertorium der lateinischen Sermones des Mittelalters für die Zeit von 1150-1350, Vol. 5. Münster: Aschendorff, 1974, pp. 65-134.

CHARLES T. DAVIS