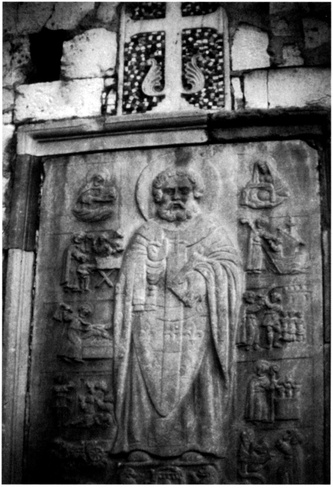

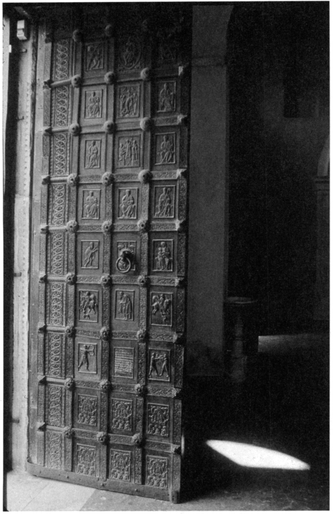

Saint Nicholas and Miracles, relief on east wall of the church of San Nicola, Bari. Photograph courtesy of John W. Barker.

See Giovanni Balbi da Genova

A ballata is a poetic arid musical form. This brief lyric consists of an initial stanza with a unique meter and rhyme scheme, called the ripresa or ritornello (refrain), followed by one or more stanzas with a common meter and rhyme scheme. These stanzas are divided into two parts: a fronte and a sirima; the sirima concludes with one or more verses that borrow meter and rhyme from the ripresa. The ripresa establishes the theme of the composition. In performance, the stanzas are associated with a solo voice and the ripresa is associated with a chorus.

The structure of the ballata (plural, ballate) resembles Provencal dance compositions of a metrical type that reached its mature form at the court of Charles of Anjou in Provence. The genre was diffused in Tuscany in the mid-thirteenth century, and the first Italian ballate were composed by the Siculo-Tuscan school of that period. In the early fourteenth century, Dante reaffirmed the link between the ballata form and dance (De vulgari eloquentia, II.3.5).

The recurring pattern of rhyme and theme in a ballata is reminiscent of the ancient rhetoric of praise, Jacopone da Todi (c. 1230-1306) established an enduring tradition of Christian hymns of praise, or laude, in the ballata form, with compositions such as O iubelo del core. The master of the secular ballata was Guido Cavalcanti (c. 1255—1300), whose extant corpus includes eleven ballate but only two canzoni. De Robertis (1961) has shown that Cavalcanti's fluid, natural amplification of ideas within the stanzas of hendecasyllabic ballate distinguishes them from contemporary canzoni, in which there is a more rigorous marshaling of arguments. This was a major contribution to the dolce stil nuovo, and an essential lesson that Dante learned from Cavalcanti, who was one of his earliest friends. Cavalcanti's most celebrated ballata, Perch'io no spero di tornar giammai, is composed in hendecasyllables and heptasyllables. The rhyme form of the ripresa is Wxxyyz and that of the stanzas is ABAB Bccddz (hendecasyllables are represented by capital letters). Cavalcanti expands the expressive potential of the recurring rhyme, engaging it in conversation with the stanzas, as Ugo Foscolo pointed out in the early nineteenth century.

The ballata form was explored by exponents of the dolce stil nuovo, including Dante and Cino da Pistoia, but Dante considered it inferior to the canzone, though superior to the sonnet. Francesco Petrarca, who included only seven mono- or distanzaic ballatas in his Canzoniere, diminished the prestige of the genre relative to the canzone and the sonnet. Boccaccio, in the Decameron, describes the singing of ballate and accompanying dances as part of each evening's entertainment, and other fourteenth- and fifteenth-century novellieri like Sacchetti and Bandello followed his lead, interpolating ballate into their prose and thus widening the breach between the ballata and more "elevated" lyric genres.

See also Ars Nova; Boccaccio, Giovanni; Canzone; Cavaicanti, Guido; Dante Alighieri; Dolce Stil Nuovo; Italian Poetry: Lyric; Italian Prosody; Jacopone da Todi; Petrarca, Francesco; Sonnet

LAURIE SHEPARD

Asperti, Stefano. Carlo d'Angiò e i trovatori. Ravenna: Longo, 1995.

Boyde, Patrick. Dante's Style in His Lyric Poetry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1971.

Cavalcanti, Guido. Rime: Con le rime di Iacopo Cavalcanti, ed, Domenico De Robertis. Turin: Einaudi, 1986.

Contini, Gianfranco, ed. Poeti del Duecento, 2 vols. Milan and Naples: Ricciardi, 1960.

Dante, De vulgari eloquentia, ed. Pier Vincenzo Mengaldo. Padua: Antenore, 1968.

De Robertis, Domenico. Il libra della vita nuova. Florence: Sansoni, 1961.

Gorni, Guglielmo. Metrica e analisi letteraria. Bologna: Il Mulino, 1993.

Banking in the modern sense, like much of modern business practice, has its roots not in the ancient world but in the economic revival of Mediterranean Europe that began in the tenth century. Nonetheless, to the extent that medieval banking practices were influenced by legal norms codified in Justinian's Digest, Roman concepts survived. Banking institutions in the western Roman empire existed to provide safekeeping for valuables, to make large- and small-scale credit available, and to perform exchange operations. As the western empire broke up, its economy regressed in comparison with the surviving eastern empire or, after the seventh century, the Islamic world. There was no longer any necessity for the more sophisticated mercantile functions of banking. Demands for credit were almost exclusively for consumption loans, to buy either luxuries for the well-to-do or essentials for those in dire straits.

The localization of minting and the consequent proliferation of coins in a bewildering variety of types, designs, fineness, and weights virtually ensured that money changers were a part of any sizable medieval community. Although evidence is scanty and often ambiguous before the thirteenth century, the great banks which appeared in Italy during that century are generally believed to have evolved from money-changing operations. In Florence, bankers in the great age of the Bardi, the Peruzzi, and the Medici were members of the Arte del Cambio, the money changers' guild. The earliest documents recording the activities of money changers are found among the twelfth-century notarial chartularies of Genoa. The term bancherius—derived from the carpet-covered table or bench (banchus) over which the exchanges were made—was already in use in the mid-twelfth century as a synonym for cambitor, although despite this terminology the money changer was not yet a "banker." By the last quarter of the twelfth century Genoese bancherii were accepting deposits and making loans, so the transition to banking had begun. Moreover, the priority of Genoa in the record may reflect simply the preservation of documents rather than any precocious development of banking there.

The nature of their business required money changers to have considerable sums on hand in coin. It would have required only a small extension of the concept of exchange for the money changer to advance a sum in anticipation of receiving coins to complete an exchange at a later date. In both Roman law and canon law a mutuum was a consumption loan that required the borrower to return only the equivalent value of what had been lent. In Roman law any agreement for a return of more than was lent had to be promised in an additional stipulatio that was not legally a part of the mutuum contract. In later Roman law, the amount of interest that could be charged was limited. Canon law, heavily influenced by the corpus iuris civilis, prohibited such interest agreements altogether. Since the mutuum was a consumption loan, the prevailing image in the agrarian society of the early Middle Ages was of someone who needed food or seed grain borrowing under the threat of destitution. To impose an additional charge in such a situation would have been contrary to the requirements of Christian charity. An advance in an exchange operation, however, might not have been conceived of as a loan at all, and any charges involved could have been thought of as having been levied on the exchange operation rather than as a return on a loan.

Furthermore, money changers must have had strong rooms, or at least strongboxes, to keep their coins safe from thieves. It is only natural, then, that anyone who had coins or other valuables might leave them with a money changer for safekeeping. Again, Roman law provided a legal framework for depositurm: one person's giving some thing (res) into the custody of another. In the simplest form of the depositum, the custodian was expected to return the same res to the depositor exactly as it had been left with him. One can imagine a sealed bag of coins, marked by a depositor, being returned exactly as it had been left. But money—unlike a horse or an heirloom—is fungible (res fungibilis): i.e., the exact equivalent value of certain things, such as coins, grain, oil, and wine, can be restored to a depositor without returning exactly the same thing that was deposited. Thus Roman law also recognized the depositum irregulare, which required returning something of equivalent value, but not necessarily the res ipsum (the very thing, the thing itself). In a contract involving depositum the custodian was obliged to return the res and any increase that might have occurred. For example, if a pregnant mare gave birth to a foal while on depositum, the custodian had to restore both mare and foal to the depositor, though the custodian had the right to recover any expenses incurred in keeping the res—in this example, the cost of feeding the mare and foal. Furthermore, the custodian had an obligation to exercise due diligence in caring for the res; and having done so, he was not liable for theft or damage outside his control. In a depositum irregulare, the ownership (dominium) of the res was transferred. After a specified period of time the custodian was required to return an equivalent value to the depositor. The custodian was responsible for any losses, even accidental losses, but was not obliged to return any increase or profit he made from the use of the res. The depositum irregulare was not considered a mutuum, because it was a contract undertaken primarily for the benefit of the depositor, even though the custodian had the right to make use of the res during the specified period. Also, in Roman law, interest could be paid, and it should be paid if the custodian was late in restoring the deposit to the depositor.

These concepts of mutuum and depositum, rooted in Roman law, continued to influence the development of banking in the Middle Ages. Canon law, which took most of its structure from Roman law, had an enormous effect. The church's teachings on usury shaped the way medieval banks did business, and the influence of Roman law ensured that the church's consideration of the matter would be in legal terms. The payment of interest, both on deposits and on loans, is at the heart of the business of banking. Yet in both civil and canon law such payment was dubious and very much dependent on circumstances. The mutuum, a loan in its simplest form, did not oblige the borrower to return anything beyond the principal. Canon law was clear on this: any return at all beyond the principal was usury, condemned in law and in the confessional. The church, however, recognized that in some circumstances the lender might suffer damages or incur expenses as a result of making a loan, and such an instance it was licit to receive compensation. It was also acceptable to receive a penalty payment if a loan was not repaid at maturity. There were loopholes, then, in the prohibition of usury, and canon lawyers and scholastics debated the fine points at length. Loans at interest were made—both overtly and covertly—but they incurred the condemnation of the church and the opprobrium of the community. Large-scale merchant bankers preferred to avoid these consequences, but in this area of economic activity the church's teaching and the community's attitudes were ambiguous.

Only if there was a mutuum could there be usury. Other kinds of transactions did not entail being condemned as usurious. Many kinds of contracts involved transferring capital temporarily from one party to another and were not considered loans, though to the modern eye the distinction might seem finespun. One of the most common contracts in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries was the commenda, in which one party in a single venture commited capital to the other party, who traveled to carry out the active role; both parties shared in the profits and losses of the venture. There were also various kinds of partnerships and other investments that accomplished similar purposes. However, necessity and the church's doctrine on usury combined to make the exchange contract—the cambium—the central business feature of medieval and early modern banking.

Manual exchange, that is, the physical exchange of coins of one kind for coins of another kind across a carpet-covered bench, remained the province of the local money changer. But by the early thirteenth century, the letter of exchange was a favorite means of transferring capital for a period of time at a profit. A charge for foreign exchange was not considered interest on a loan, because it involved cambium rather than mutuum. Exchange carried out by means of a bill of exchange involved payment in one kind of coin in one place, and collection—usually in another kind of coin—in another place. The time that elapsed was merely due to distance and so did not make the cambium a loan, though the effect could be much the same. In the end, while lawyers and scholastics debated the technical aspects of usury, laymen came to the widespread conclusion that only a guaranteed return on a loan constituted usury; an uncertain return avoided this taint, A return on a depositum irregulare could be justified as a gift or as a share of profits realized by the banker through use of deposited funds. The commenda, various partnerships, and other contracts did not guarantee a specific rate of return, or indeed any return at all, and some of these arrangments entailed a risk of loss. Exchange rates could vary between the issuance of a bill of exchange and its presentation. The doctrine concerning usury, then, did not prevent bankers from using their depositors' capital for profit; but to the extent that it discouraged consumption loans, it might have channeled capital into business investment, thus benefiting the medieval economy. It certainly pushed medieval banking in the direction of exchange banking.

By the late twelfth century, bankers were using funds deposited with them to make investments in commercial enterprises and to make credit available to third parties. In 1200, a Genoese banker promised a woman who had deposited fifty lire genovese in his bank that he would "employ them in trade in Genoa so long as it shall be your pleasure; and I promise to give you the profit according to what seems to me ought to come to you."

Such arrangements required relatively sophisticated record-keeping. Accounting, and ultimately double-entry bookkeeping, developed as banking operations became larger and more complex. Even at a relatively rudimentary level, these records made it possible for bankers to make book transfers from one client's account to another. By the early thirteenth century, merchants would routinely call at the bench where their banker did business to give an oral order for payment by debiting the payer's account and crediting the payee's. Almost as quickly, it became possible for clients of different bankers to settle debts by means of transfers between banks, because in most Italian cities the bankers commonly carried on their business in the same location, facilitating quick oral communication among them. In Genoa, the benches were set up in the Piazza Banchi near the port. In Venice, bankers gathered at the Rialto. Bankers in Lucca congregated in the Piazza San Martino in front of the cathedral. Bankers in Florence, perhaps because there were so many of them, formed several centers: the Mercato Nuovo, Mercato Vecchio, and Or San Michele were the most important. Perhaps because their activity was so dispersed, the Florentine bankers seem to have led in the development of the check, a written rather than oral order to a banker to transfer funds from one account to another.

Though banking had its origins in money changing, the largest banks of medieval Italy were merchant banking houses. Italian merchants were prominent at the fairs of Champagne and other wholesale markets in northern Europe. Records show definitely that merchants from Siena were active there in 1216, and there is evidence from the 1220s that they were engaged in both mercantile and banking activities. Italian companies engaging in trade beyond the Alps would have needed to make frequent large exchanges between the currency of their home city and that of the foreign areas where they did business. It must have been very inconvenient to transport large amounts in specie for that purpose, so large firms with a great deal of capital soon arranged to achieve the same result by making transfers in their account books. Very large companies could offer these exchange services to third parties. The bill of exchange (lettera di cambio) was developed to meet this need. A bill of exchange was initiated when one party, the deliverer or remitter (datore, remittente) in, say, Siena, gave money or something else of value to the taker (prenditore, pigliatore) in return for a bill of exchange. The remitter then sent the bill of exchange to a payee, who was usually his correspondent in a foreign city—London, for example. That payee would then complete the transaction by presenting the bill at maturity to the payer (pagatore) for collection. The original remitter finally realized his return on the transaction with a second bill of exchange from the foreign place to his home city for which he became the payee. At least two bills were involved in a complete exchange cycle for a banker, and three were not uncommon. Most bills of exchange were payable at usance (a usanza, "according to custom"), that is, after a period related to the usual time required for a journey between the city where the bill was issued and the place where it was to be presented. Thus, if exchange was used in place of a loan, the period could be determined by the distance between the cities involved. This might vary from ninety days between Florence or Venice and London to five days between Florence and Venice. Of course, it was possible to draw up a bill of exchange and reexchange that guaranteed a certain rate of return to the remitter, or even obviated any exchange by including a clause that gave the taker (for all practical purposes, the borrower) the option of repaying in local currency. This so-called "dry exchange" was, quite simply, a disguised loan at interest. It was recognized as such and condemned by the church as usurious. Still, it was a common practice.

The greatest single client for banking services of all kinds was the papacy, along with other prelates. General taxation of the clergy by the papacy began under Innocent III (1198-1216). Papal taxation in itself required the transfer and exchange of large sums from all over western Europe to Rome. Sienese merchant banking companies were well placed to fill this need. They had the necessary capital; the technical means had been worked out; and of all the burgeoning northern Italian cities, Siena was closest to Rome. Financing the papacy became a very large part of the banking business of the Tuscan companies in Florence and Lucca as well as Siena. In the second half of the thirteenth century, by serving as bankers to the popes, the Gran Tavola dei Bonsignori became the greatest of the Sienese companies. Almost as large was the Ricciardi bank of Lucca. Both were heavily involved in providing financial services to the church. The conflict between Innocent IV (1243-1254) and Emperor Frederick II rapidly increased the fiscal needs of the papacy. Although Siena's active support of the Staufen cause must have created problems for the Bonsignori, the firm successfully managed them and continued to grow for the next generation or more. By the 1290s, however, the Bonsignori began to experience difficulties. In 1298 it collapsed, and in the following decades several more Sienese banks failed. During this period, and especially during the pontificate of Boniface VIII, the papacy began to transfer much of its business to banks in Florence, a city that was firmly Guelf.

The fourteenth century was the great age of Florentine banking. The Bardi, Peruzzi, and Acciaiuoli were the great international banking houses of the first half of the century. There were also many smaller companies, some of which operated internationally, others only locally. Like their thirteenth-century predecessors, these were merchant banking companies, engaged in trade and manufacture as well as in finance, but the larger firms tended to lean more toward the financial side. The dominance of Florentine companies is graphically illustrated by the success of the florin, a gold coin first minted in 1252. The florin circulated widely throughout western Europe and the Mediterranean. It became the standard of international trade and banking to such an extent that debts which might be paid in other coins, or even in kind, were often quoted in florins. The far-flung span of the Florentine banking and trading houses is illustrated by a handbook written c. 1340 by Francesco Balducci Pegolotti, a branch manager of the Bardi company. Francesco had represented the Bardi in London and Cyprus and had accumulated a wide knowledge of trade and finance; he opens his handbook with a famous description of the "journey to Cathay" and goes on to discuss weights, measures, and business conditions from Constantinople to London.

Unfortunately, the Italian banks found that finance at the highest levels, dealing with popes and kings, could be dangerous as well as profitable. The final blow to Siena's dominance of European banking came when the French king Philip IV (1285-1314) confiscated the property of Sienese merchants in France in compensation for money that he claimed he was owed by the Bonsignori. This action, coming as it did at the same time that Boniface VIII was withdrawing papal business from Siena, sealed the fate of the Sienese bank. Florentine bankers also found Philip a dangerous client, but it was in England that the great Florentine houses became most entrapped by involvement in royal finance. Since the late thirteenth century, these houses had often made large loans to English monarchs and had, in return, received favored treatment in the lucrative wool trade. The debts, secured by future tax receipts, seemed safe enough so long as relations with the king continued to be amicable—but the English kings were perpetually in need of money, and their amity was maintained only at the price of further loans. The Florentine banks thus became more and more deeply involved with royal debt. In 1336, King Edward III decided to pursue his claim to the French throne, and he expected the Bardi and Peruzzi companies to finance this war. It is a measure of their wealth that they did so for almost a decade. When Edward ultimately defaulted on his enormous debt to the banks (estimated by the contemporary Florentine chronicler Giovanni Villani as more than 1.3 million florins), the English branch of the Bardi was bankrupted. This bankruptcy set off a run on the banks in Florence that dragged down the home offices of the Bardi and Peruzzi, starting a wave of business failures in Florence in the mid-1340s. The economic disaster was soon followed by a demographic disaster: the black death of 1348. The Florentine financial sector reeled from this double blow.

Not until the last decade of the fourteenth century did another great banking house arise in Florence and assume international prominence, that of Giovanni di Bicci de' Medici, in the fifteenth century, the Medici bank would become the leading bank, with branches all over Europe. Under Giovanni and his son Cosimo, the finances of the papacy continued to be the largest single element in the growth of the Medici bank. But because of the economic contraction during this period, only one such bank could exist where before there had been many, and by any measure—capitalization, number of employees, or number of branches—that bank was smaller than the Bardi and Peruzzi houses of the early fourteenth century.

See also Bardi Family; Bookkeeping, Double-Entry; Coins and Mints; Florence; Peruzzi Family

JOHN E. DOTSON

Banchi pubblici, banchi privati, e monti di pietà nell'Europa preindustriale: Amministrazione, tecniche operative, e ruoli economici—Aatti del convegno, Genova, 1-6 ottobre 1990. Atti della Società Ligure di Scoria Patria, n.s., Vol. 31, fasc. 1-2. Genoa: Società Ligure di Storia Patria, 1991.

Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, University of California, Los Angeles. The Dawn of Modern Banking. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1979.

De Roover, Raymond A. L'évolution de la lettre de change, XIVe-XVIIIe siècles. Paris: A. Colin, 1953

—. Business, Banking, and Economic Thought in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe, ed. Julius Kirshner. Chicago, Ill.: University of Chicago Press, 1974.

Goldthwaite, Richard A. Banks, Palaces, and Entrepreneurs in Renaissance Florence. Aldershot, Hampshire; and Brookfield, Vt.: Variorum, 1995.

Lane, Frederic C. "Investment and Usury." Explorations in Economic History, 2, 2nd ser., 1964. (Reprinted in Venice and History: The Collected Papers of Frederic C. Lane. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1966.)

Melis, Federigo. La banca pisana e le origini della banca moderna, ed. Marco Spallanzani. Florence, 1987.

Mueller, Reinhold C. The Venetian Money Market: Banks, Panics, and the Public Debt, 1200-1400. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997.

Noonan, John. The Scholastic Analysis of Usury. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1957

Renouard, Yves. Les relations des papes dAvignon et des compagnies commerciales et bancaires de 1316 à 1378. Paris: E. de Boccard, 1941.

Sapori, Armando. La crisi delle compagnie mercantili dei Bardi e dei Peruzzi. Florence: Oischki, 1926.

Usher, Abbot P. The Early History of Deposit Banking in Mediterranean Europe. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press 1943. (Reprint, New York, 1967.)

See Flags and Banners

Barbato (c. 1300-1363) is known primarily for his friendship with some of the leading intellectuals of the Trecento. He was born in Sulmona (the exact date is not recorded), and Barbato was his Christian name—not his surname, as was erroneously supposed for many years. He qualified as a notary on 4 January 1325 and then began working at the Angevin court in Naples. In the course of his life he met many notable scholars, of whom the most famous were Petrarch and Boccaccio.

Barbato and Petrarch first met when Petrarch visited Naples in the spring of 1341, and much of their correspondence has been preserved. Twenty-two of Petrarch's letters to Barbato are extant, and attached to one of them is a rare surviving example of Barbato's own writing, Romana res publica urbi Rome, probably composed in 1347. In addition, we have three letters from Barbato to Petrarch, and a fourth which was written by Barbato to Petrarch on behalf of Niccolò Acciaiuoli, Napoleone, and Nicola Orsini. Barbato also wrote a learned commentary on Petrarch's letter to Niccolò Acciaiuoli, Iantandem (Familiarum rerum libri epistole, XII.2). Barbato was instrumental in the manuscript tradition of Petrarch's writings, collecting them and diffusing them among the Neapolitan intellectual community, and Petrarch dedicated his Epistolae metricae to Barbato, perhaps in recognition of this.

Barbara's friendship with Boccaccio began in Naples in 1344. Three letters from 1362—one by Boccaccio and two by Barbara—are all that remains of their correspondence, but they demonstrate Barbara's lifelong devotion to Petrarch and are evidence of his search for further examples of Petrarch's writing. Boccacio, in his letter, promises Barbara a copy of Petrarch's Bucolicum carmen.

Barbato died of the plague during the autumn of 1363.

See also Boccaccio, Giovanni; Petrarca, Francesco

GUYDA ARMSTRONG

Campana, A. "Barbato da Sulmona." Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, 6, 130-134.

Petrarch (Francesco Petrarca). Familiarum rerum libri epistole, ed. Ugo Dotti. Turin: UTET, 1978, pp. 43-543.

Vattasso, Marco. Del Petrarca e di alcuni suoi amki. Rome, 1904, pp. 7-33.

Weiss, R. "Some New Correspondence of Petrarca and Barbato da Sulmona." Modern Language Review, 43, 1948, pp. 60-66.

A euchologium is a liturgical book containing the eucharistic formulas, sacramental rites, and other public prayers of the Greek church. For the Byzantine rite—representing the majority of that church—the oldest surviving example is the Barberini Euchologium in the Vatican Library (Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Codex Barberinianus Graecus 336, folios 1-263), written in southern Italy in the second half of the eighth century. The Barberini Euchologium predates by many centuries the eventual definitive form of the rite, from which it differs in important respects. It is also the oldest document of the Italo-Greek liturgy celebrated in various forms throughout the Middle Ages and into the early modern period; thus it occupies a special place among the manuscript remains of Greek culture in medieval Italy. The Barberini Euchologium has long been known to scholars but has only recently received a modern critical edition.

See also Greek Language and Literature; Greek Orthodoxy in Italy

JOHN B. DILLON

Parenti, Stefano, and Elena Velkovska, eds. L'eucologio Barberini gr, 336 (ff. 1-263), 2nd rev. ed. Bibliotheca Ephemerides Liturgicae, Subsidia, 80. Rome: C.L.V.-Edizioni Liturgiche, 2000. (With Italian translation.)

Cacciotti, Alvaro, ed. "L'eucologio Barberini gr. 336: Il più antico testo liturgico delle chiese bizantine." Antonianum, 71, 1996, pp. 590-604.

Taft, Robert F. The Byzantine Rite: A Short History. Collegeville, Minn.: Liturgical Press, 1992.

The Bardi, a Florentine family, ran one of the premier European banking houses in the late Middle Ages. In the twelfth century, members of the family moved from the vicinity of Antella to Florence and established houses near the Arno River along what is now Via dei Bardi. They were vigorous traders in wool and leaders in the Florentine Calimala guild, and they had an office in England perhaps as early as 1183. After 1234, their fortunes soared, and in 1263 four brothers, the sons of Buonaguida Bardi, established the family bank sn Florence. Two years later they were lending to the pope.

The Bardi family was large, with many branches, and several members became prominent in politics during the thirteenth century. For example, Bartolo di messer Iacopo served in Florence's first priorate in 1282 and subsequently in 1283, 1285, 1286, and 1290. The Bardi's fortunes dipped after King Edward I of England sequestered their English wool stocks in 1290. However, in the 1290s, the Bardi established branches of their bank in Naples, Friuli, Udine, Cividale, Cremona, and Aquileia. They were declared magnates under the Florentine ordinances of justice (1293), and they feuded with a rival banking family, the Mozzi (1290-1295). Beginning in 1303, they served as mercanti di camera for the pope.

During the first third of the fourteenth century, the Bardi continually expanded their commercial and banking interests. In 1299, six brothers, sons of Iacopo di Riccio, and five other Bardi controlled the enterprises; and in 1310 there were fifteen partners, ten from the same family. In a good year, interest and dividends for investors would reach 13 percent. Along with their giant contemporaries the Acciaiuoli, the Frescobaldi, and the Peruzzi, the Bardi supplanted earlier families as bankers to the monarchs of Europe. The rulers needed cash, and in exchange for it they would often grant monopoly rights to state export revenues. The Bardi controlled many such monopoly revenues—for example, wheat in Naples—and, along with the Peruzzi, they had a virtual lock on English wool exports under Edward III. Nonetheless, kings could be troublesome clients, and disaster struck in May 1339. Edward III had borrowed nearly 1,365,000 gold florins to finance a war against France, and he owed payments on 800,000 florins to the bankers. When the fortunes of war forced him to suspend payments, other debts were called in, there was a run on all the Florentine bankers, and the economy of Florence nearly collapsed. The banks were ruined, but thanks to state-imposed moratoriums and its own diverse resources the Bardi bank survived until its creditors seized its assets in 1346.

In November 1340, in the immediate aftermath of this disaster, the Bardi led other magnates in a rebellion against the popular government. They were defeated, and sixteen members of the Bardi family were banished from Florence. Because they gave support to Walter of Brienne, they were able to return to the city two years later; but when Walter refused to abrogate the Ordinances of Justice, the Bardi participated first in his overthrow and then in the oligarchical "fourteen" who ruled in his wake.

The Bardi had been the strongest political and economic force in Florence in the 1330s, and they retained much of their power even after the bankruptcy. In 1364, they numbered fifty-two households, and in 1377 they were denounced as a "great and arrogant family." Members of the Bardi family continued to serve in political and diplomatic offices, and several were professional podestas. Others—-such as Roberto, a theologian at Paris (d. 1349); and Bartolomeo, bishop of Spoleto (from 1320)—served the church. The family also patronized several Florentine churches; the famous Bardi Chapel in Santa Croce was decorated by Giotto.

See also Banks and Banking; Florence; Guilds; Walter of Brienne

JOSEPH P. BYRNE

Becker, Marvin. Florence in Transition, 2 vols. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1967.

Davidsohn, Robert. Storia di Firenze, 8 vols. Florence: Sansoni, 1956-1968.

Holmes, George. Florence, Rome, and the Origins of the Renaissance. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986.

Long, Jane Collins. "Bardi Patronage at Santa Croce, 1320-1339." Ph.D. dissertation, Columbia University, 1988.

Prestwich, M. "Italian Merchants in Late Thirteenth and Early Fourteenth Century England." In The Dawn of Modern Banking. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1979.

Russell, Ephraim. "The Societies of the Bardi and the Peruzzi and Their Dealings with Edward III, 1327-1345." In Finance and Trade under Edward III, ed. George Unwin. London: Cass, 1962, pp. 93-135. (Reprint of 1918 ed.)

Sapori, Armando. La crisi della compagnie mercantili dei Bardi e dei Peruzzi. Florence: Olschki, 1926.

Bari is today the second largest city of southern Italy, the major city of modern Puglia (Apulia), and the most important port on Italy's Adriatic coast. Its origins have been traced back to the Bronze Age, and its foundation has been attributed to Illyrian settlers. It was inhabited by a people called the Peucezi, who occupied the Adriatic coastal regions of Apulia by the time the Greeks penetrated the area. It came into Roman hands during the third century B.C., and because it was situated at a junction of major roads, it became an important municipality and commercial center during the Roman era, though it was subordinate to Brindisi as a port and as a focus for shipping directed to the eastern Mediterranean. Christianity was well established in Bari by 347, when the first mention is made of its bishop.

With the disruption of Roman rule in the fifth century, Bari became first a part of the realm of the Ostrogoths and then, after Justinian's reconquest, part of the Roman-Byzantine regime. The Lombards under Authari seized Bari, but it was still strongly contested by the Byzantines, and it was sacked by Emperor Constans II in 669. Duke Romuald of Benevento (d. 687) held it briefly, only to lose it again to the Byzantines. Their rule over Bari was soon shaken, however. The Baresi opposed the new Iconoclastic policies of Emperor Leo III (c. 680-741) and rebelled against him; they then maintained their independence under a series of leaders (Theodore, Angelbert, and others). At this time Bari became the seat of the primate of Apulia, surpassing its rivals Brindisi and Taranto as an urban and ecclesiastical center. In early ninth century it was under the rule of its own duke, Pandone, who recognized a loose Byzantine suzerainty but then fell under the control of Duke Radelchis of Benevento. In the course of local struggles, African Saracens were drawn into the region, and in 847 Bari was stormed and was made the capital of an emirate—the only Islamic regime ever established on the Italian mainland, and a hint of what could have become a larger Saracen, or Arab, conquest.

In fact, however, the Saracen emirate, and whatever prospects it represented, lasted barely twenty-five years: in 871 it was besieged and taken by the Frankish emperor Louis II. When Louis died in 875, Bari again submitted itself to Constantinople, becoming the center of the restored Byzantine rule in southern Italy as the residence (from 893) of the strategos of the theme (military district) of Langobardia. During the Ottonian penetration of southern Italy, Bari was briefly taken by Otto I; but in view of the weakness of his son, Otto II, Bari was returned to Byzantine rule by 982, and it became the seat of a still higher official, the katepano, who commanded an enlarged complex of Byzantine territories (including Apulia and Calabria). At the same time, the Saracens continued to threaten Bari, and in 1002 a Sicilian force under Safi besieged the city, which resisted heroically. Relief came when the Venetian fleet, led by Doge Pietro Orseolo II, appeared at the request of the Byzantines and dispersed the attackers.

During these phases of Byzantine rule, Bari became a large and prosperous metropolis with a polyglot population and a cultural life enriched by Byzantine culture, and its maritime and mercantile elements benefited from their connections with the markets of Constantinople. Nevertheless, with regard to religious loyalties, Bari's population remained staunchly western Catholic; and periodically, restless elements in and around the city made it a hotbed of resistance to the Byzantine government, which was considered oppressive. A climax came with a series of rebellions organized by the Lombard Melo, who was supported by local Lombard princes and by the German emperor Henry II. Melo's first venture (1009) failed. For his second attempt (1016), he called on Norman adventurers who were then appearing in Italy as mercenaries; bur he was decisively defeated at Cannae (1018) by the energetic new Byzantine katepano Basil Boioannes, went into exile, and died in Germany.

Under Boioannes, Byzantine control was revitalized, though at the cost of recurrent wars with the Lombards of Benevento and with Saracen raiders. Bari was again a powerful urban center as seat of the katepanate, but the local populace remained resentful. After Boioannes died, this resentment was exploited by Melo's son Argyrus, who escaped captivity in Constantinople and fomented new rebellions in Italy. Argyrus, like his father, was aided by Norman mercenaries, and he was able to enter Bari, where he was acclaimed its duke. He was held in check during the harsh regimes (1037-1040, 1042) of the Byzantine commander George Maniakes. When Maniakes departed, in an abortive attempt to usurp the throne in Constantinople, Argyrus resumed his rebellion, but he now found himself pushed aside by his Norman allies, who were seizing territories for themselves. Argyrus soon crossed over to the Byzantine side, and in 1045 he went to Constantinople, where he became active at the court. Having gained the emperor's confidence, Argyrus was sent back to Italy as Byzantine governor and duke of Bari. He and his successors held the city in the name of Constantinople as the Normans proceeded to conquer more and more of southern Italy. Eventually, Bari was left as the Byzantines' last toehold and was besieged for four years by the paramount Norman leader, Robert Guiscard. Starved into submission, it surrendered in 1071, completing the extinction of Byzantine rule in Italy. Guiscard ruled Bari through a deputy, and upon his death (1085) the city became part of the inheritance of his eldest son, Bohemond, although Bohemond's rule was challenged for a while by another son, Roger.

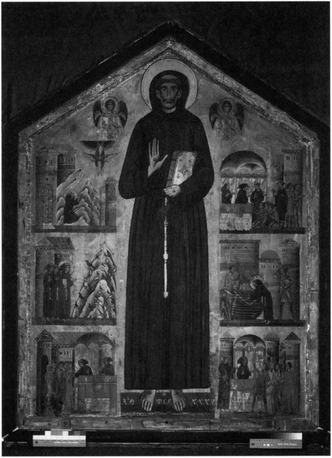

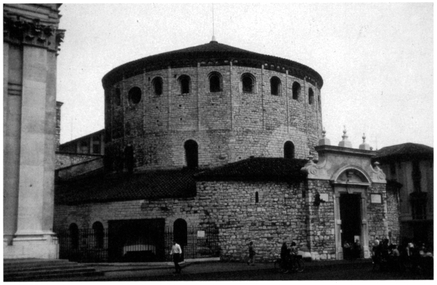

In 1087, some Barese sailors succeeded in stealing the relics of Saint Nicholas of Myra from the church in Asia Minor where the saint had been buried, and carrying them off to Bari. The relics were entrusted to Abbot Elia of the Benedictine monastery and, after some dispute over where to place them, Elia (by then a bishop), with the patronage and support of Roger, began the construction of a new church dedicated to Nicholas, who was proclaimed the patron saint of Bari. At this time, the cult of Saint Nicholas was becoming ever more popular in the Christian west, and Bari became one of the most important shrines and pilgrimage sites in western Europe. (To this day, Bari has a huge annual festival celebrating this saint.) In 1098, in the newly completed crypt of the church of Saint Nicholas, Pope Urban II, who had recently preached the First Crusade (then still in progress), held a council aimed at reconciling the Latin and Greek churches. Saint Anseim of Canterbury was among the participants.

In addition to the pilgrimage to the shrine of Saint Nicholas, pilgrims on their way to the Holy Land in the wake of the crusades also passed through Bari, making it a major center of east-west transportation and a highly prosperous port. But the Baresi found the Normans' rule oppressive, and in the years following Bohemond's death (1109), the city again became a center of unrest and struggle. One of Bohemond's successors, Duke Grimoald of Bari, attempted to fend off the new Norman king, Roger II. In 1136, at the behest of the pope, the German emperor Lothair II took advantage of the confusion, seized the city, and occupied it briefly. Thereafter Bari went, tumultuously, through one form or another of Norman lordship until 1155. That year, in accordance with the will of the people, the city was handed over to the Byzantine emperor Manuel I, who was making a fumbling attempt to recover power in Italy. In 1156, in retaliation, the Norman king William I, "the Bad," besieged the city, stormed it, and razed it to the ground, sparing only the church and shrine of Saint Nicholas. A decade passed before the population regathered; the city was then rebuilt under William II, "the Good," and the upper part of the basilica of Saint Nicholas was consecrated by a papal legate.

Saint Nicholas and Miracles, relief on east wall of the church of San Nicola, Bari. Photograph courtesy of John W. Barker.

From then on Bari recovered steadily as it passed from the rule of the Normans to that of the Swabian Hohenstaufen and entered a more stable period. However, its former turbulent autonomy was decisively reduced. Frederick II, doubtful about the city's loyalty but determined to ensure its strategic importance, rebuilt and expanded its commanding fortress and also built a new port. He also granted the city certain selected privileges, confirmed its episcopal status in the region, and instituted at Bari one of seven annual fairs that were to be held in his kingdom.

Bari's revival, and its new prosperity, dissolved with the coming of Angevin rule. The Angevin sovereigns, selfish, quarrelsome, decadent, and exploitative, cared little for the interests of the city and sought only to extract from it what revenues they could. Commercial privileges were callously sold to wealthy merchants, and arrogant noble families flaunted their power with impunity. Worse still, the city became a pawn in conflicts between branches of the Angevin dynasty. Bari supported Queen Joanna I of Naples against Louis of Hungary, and as a result the city was besieged by an army of Hungarians and Germans and was forced to surrender (1349). After the war, Joanna ceded the city in turn to Robert of Anjou, prince of Taranto, and then (in 1364) to his brother Philip. It next fell under the rule of the rebellious Iacopo del Balzo, who was followed by Joanna's fourth husband, Ottone. In the ensuing struggle between two branches of the dynasty—Naples and Durazzo—Bari unwisely and futilely sided with the Neapolitans Louis I and Louis II and then suffered the vengeance of the victorious Durazzan faction. Under King Ladislas and even under Joanna II, Bari was granted some new rights and immunities, but these were abridged when, in 1430, Joanna again awarded the city in feudal grants in turn to Iacopo Caldora and his son Antonio. After a brief and unhappy period of Aragonese rule, Bari passed in 1464 into the hands of members of the Milanese Sforza family, including the widowed Isabella of Aragon. Under Isabella's reign (1500-1524) the city enjoyed one last, short period of revival, refurbishing, and cultural florescence.

As a consequence of its stormy history, virtually no traces of Bari's early medieval and Byzantine monuments survive in the modern city; there are only a few putative fragments of the palace complex of the Byzantine governor, adjacent to the church of Saint Nicholas, or San Nicola. But that church and the cathedral have made Bari a glorious, and influential, example of the Romanesque architecture of southern Italy.

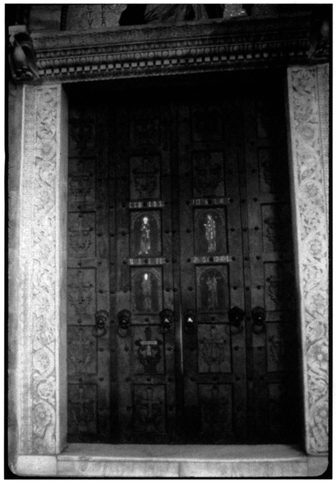

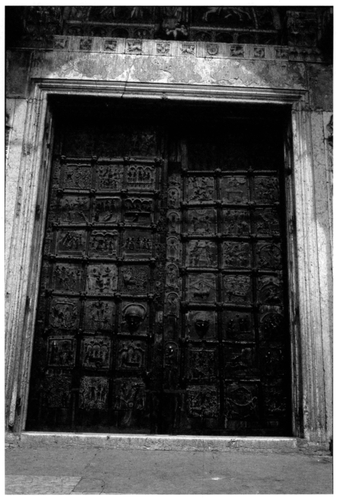

The church of San Nicola is one of the four palatine basilicas of Puglia, It was the first great Norman church erected in southern Italy, and it became the model for Romanesque design in the region. It was begun by Bishop Elia, under the patronage of Duke Roger, on the site of the palace of the Byzantine katepano, and apparently it incorporates some Byzantine fragments, especially in one or both of its facade towers. Elia built the crypt, which contains the saint's extensive burial shrine. This much was consecrated by Pope Urban II in 1089; in it, Peter the Hermit preached a sermon urging what became the First Crusade (1095), and (as noted above) Urban came here in 1098 to preside over a council. The initial phase of construction ended in 1108, three years after Elia's death. The barely finished church was spared devastation in 1156, and the upper church proper was completed in 1197, when the church was consecrated. Its exterior is severe in design but is graced on three sides by handsome portals decorated with sculptures of lions on the north side and bulls on the south side and the western facade. Inside, the church's treasures include a superb ciborium (c.1150), the oldest preserved in Puglia; and an episcopal throne that is said to date from Urban II's council in 1098. The crypt, with the saint's elaborate tomb (from which miraculous unguent or manna is still believed to flow), is decorated as befits an important pilgrimage site. The shrine includes a fine Byzantine icon, given in 1319 by the king of Serbia. At the altar complex, provision is made for the celebration of the Byzantine rite, in partnership with the Latin rite; Bari is one of the few places in Italy where this is allowed.

The cathedral, dedicated to San Sabino, is modeled closely on San Nicola but is on a grander scale; it is a noteworthy example of Apulian Romanesque design. It replaced a series of earlier episcopal churches dating from early Christian times to the Byzantine era. Its immediate predecessor had been given its own definitive form by Bishop Bisanzio in the years 1035-1064, but that structure was all but totally destroyed in 1156 by William I. The present cathedral was constructed on its ruins in 1170-1178 but was not formally consecrated until 1292. Like San Nicola, the cathedral is a basilica in plan, though it is surmounted by a large cupola within an octagonal drum. On the exterior of the east wall, outside the altar, is a magnificently sculptured apsidal window. The austere interior is graced by a reconstructed ciborium of 1233. At the end of the north wall is a cylindrical structure called La Trulla, which is now used as a sacristy but was originally the baptistery of the eleventh-century church. Modern excavations have revealed extensive survivals of early mosaic pavement, dating from the eighth and ninth centuries. The cathedral archives preserve some important liturgical manuscripts, including the famous Exultet roll, a Byzantine paschal scroll of the early eleventh century.

Adjacent to San Nicola is the city's third important medieval church, San Gregorio, which is small but handsome. It was originally built in the early eleventh century, was probably gutted in 1156, and was rebuilt to some extent between the late twelfth century and the thirteenth century, in Romanesque style.

Another important monument in Bari is the massive Hohenstaufen castle, at the western corner of the medieval walls. The castle, which incorporates earlier Byzantine and Norman elements (eleventh-twelfth centuries), was essentially built by Frederick II, with amplifications by Isabella of Aragon. Here, according to tradition, Frederick received a visit from Saint Francis of Assisi. The castle is now used as a museum and exhibition center. Adjacent to it is Bari's centra storico (historic center). In general, although the centro has lost most of its actual fortification walls, it still preserves its medieval configuration—a warren of narrow, twisting streets that are said to have been made so complex deliberately, in order to baffle and frustrate attackers.

See also Authari; Bohemond of Taranto; Constants II; Francis of Assist; Frederick II Hohenstaufen; Henry II, Saint and Emperor; Joanna I of Naples; Justinian I; Leo III, Emperor; Louis II, Emperor; Maniakes, George; Normans; Ostrogoths; Otto I; Otto II; Robert Guiscard; Roger II; Urban II, Pope; William I; William II

JOHN W. BARKER

Falkenhausen, Vera von. La dominazione bizantina nell'Italia meridionale dal IX all'XI secolo. Bari, 1978.

—. "Bari bizantina." In Spazio, società, potere nell'Italia dei Comuni, ed. G. Rossetti. Naples, 1986, pp. 195-227.

Guillou, André. Studies on Byzantine Italy. London: Variorum, 1970,

—. Il Mezzogiorno dai Bizantini a Frederico II. Turin, 1983.

Kreutz, Barbara. Before the Normans: Southern Italy in the Ninth and Tenth Centuries. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1991.

Schettini, F. La basilica di San Nicola di Bari. Bari, 1967.

Barlaam the Calabrian (Bernardo Massari, c. 1290-1348 or c. 1350) was born at Seminara in Reggio Calabria and was probably educated at one of the Greek Orthodox monasteries in the region, which were important centers of Greco-Latin studies. Having entered the priesthood, he left for Constantinople sometime around 1326 or 1327. From 1331-1332 on, Barlaam also seems to have lived intermittently at Thessaloniki.

Barlaam's lectures on mathematics (he wrote on arithmetic, astronomy, acoustics, and music) and philosophy (a treatise by him on Stoic ethics is preserved) soon made him very successful in the Greek capital. Apparently, his success aroused the envy of Niceforus Gregoras, who was then the prime representative of Byzantine humanism. Barlaam's training in Latin scholastic theology proved to be an important asset in 1333: he was chosen to defend the Greek position in discussions related to a reconciliation with Rome, which was desired by Pope John XXII. Bar laam's agnostic-nominalist position, however, drew criticism, both from the nominalist papal representatives and from several Greek colleagues such as the Hesychastic monk Gregory Palamas. Barlaam later disputed with Gregory on the value of the contemplative techniques practiced by the Hesychasts, and in 1338 this dispute developed into a discussion of the value of scholastic theology versus mystical contemplation. In 1341, the debate culminated in a general council at Constantinople, where Barlaam was forced to refrain from any further attacks on Hesychasm or Palamite theology.

In July 1341, after the death of Emperor Andronicus III, Barlaam chose to return to Italy and France. Earlier, at the beginning of 1339, Andronicus III had sent Barlaam on a mission to Naples, Paris, and Avignon to seek support for a crusade against the Turks. Thus when Barlaam came back to the west, he had a circle of patrons and friends eager to extend him hospitality. It was at Avignon that Barlaam first made the acquaintance of Petrarch (Francesco Petrarca), to whom he began teaching Greek in 1342. With the help of this pupil, Barlaam acquired the Calabrian bishopric of Gerasa. In 1346, he was charged with an ecumenical mission to Constantinople, but owing to the influence of Palamas, the mission failed. Barlaam returned to the papal court at Avignon, where he remained until his death on 1 June 1348.

See also Byzantine Empire; Petrarca, Francesco

STEVEN VANDEN BROECKE

Akindynos, Gregorios. Gregorii Acindyni Refutations duae operis Gregorii Palamae cui titulus Dialogus inter orthodoxum et Barlaamitam, ed. Juan Nadal Canellas. Turnhout: Brepols; Leuven: University Press, 1995.

Barlaam Calabro. Epistole greche: I primordi episodici e dottinari delle lotte esicaste—Studio introduttivo e testi, ed. Giuseppe Schiró. Palermo: Istituto Siciliano di Studi Bizantini e Neoellenici, 1954.

—. Epistole a Palamas, ed. A. Fyrigos. Rome, 1975.

Giannelli, C. "Un progetto di Barlaam Calabro per l'unione delle chiese." In Miscellanea Giovanni Mercati, Vol. 3. Vatican City, 1946, pp. 157-208.

Migne, Jacques-Paul. Patrologia Graeca, 151, pp. 1243-1364. (Reproduces texts of several older Latin and Greek editions of theological writings.)

Barlaam Calabro, per l'Unione delle Chiese, ed, F. Mosino. Chiaravalle Centrale, 1983.

Cassiano, Domenico. Barlaam Calabro: L'umana avventura di un greco d'Occidente. Lungro: San Marco, 1994.

Fyrigos, A. "Barlaam Calabro tra l'aristotelismo scolastico e il neoplatonismo bizantino," Il Veltro, 27, 1983, pp. 185-195.

Impellizzeri, S. "Barlaam." In Dizionario biografico degli Italiani, Vol. 6. Rome, 1964, pp. 392-397.

Leone, P. L. M. "Barlaam in Occidente." Annali dell'Università di Lecce-Facoltà di lettere e filosofia, 11, 1981, 427-446.

Sinkewicz, R. E. "The Doctrine of the Knowledge of God in the Early Writings of Barlaam the Calabrian." Medieval Studies, 44, 1982, pp. 181-242.

Barna (Berna da Siena, fl. c. 1330-1350) was a Sienese painter active in Tuscany during the second quarter of the Trecento. On the basis of the style and quality of the art currently associated with him, he was among the most accomplished of Simone Martini's followers and colleagues. Barna's artistic reputation traditionally rests on his contribution to the great fresco cycle Episodes from the Infancy and Passion of Christ in the Collegiata of San Gimignano, painted in the late 1330s or 1340s by a team of three or four masters. His precise historical identity is controversial, however, since current critical opinion is that his name is fictitious. A painter called Barna Bertini was recorded in Siena in 1340, but he is not thought to be the same artist who participated in creating the cycle in San Gimignano.

Barna was first mentioned by Lorenzo Ghiberti in I commentarii (c. 1447-1455) in connection with a series of mural paintings on Old Testament subjects to be found in an unspecified church in San Gimignano; today these paintings are identified as the Old Testament cycle on the left aisle of the Collegiata. However, those frescoes were executed by Bartolo di Fredi Cini by 1367, and it has been suggested that "Barna" is simply Ghiberti's misreading of "Bartolo." Despite his Florentine background, Ghiberti was particularly sensitive to the achievements of Sienese painting, and he praised the artist he knew as Barna, who he claimed had also been active in Florence and Cortona.

Giorgio Vasari included Ghiberti's observations in his first edition of Vite (1550), but by the second edition (1568), "Berna," as Vasari refers to him, is said to have painted New Testament rather than Old Testament narratives in the pieve of San Gimignano—where, as Vasari goes on to relate, the painter's career came to an abrupt end in 1381, when he was killed in a fall from some scaffolding. Vasari increased the painter's corpus, of which nothing survives today except the frescoes in San Gimignano, and extended his sphere of activity to Arezzo and Siena. Some scholars have suggested that Vasari, while preparing his later edition of Vite, became aware of that Bartolo had created the Old Testament frescoes and therefore associated Ghiberti's Barna with the only other great fresco cycle in the church, the New Testament scenes on the opposite wall or right aisle of the Collegiata. In the process, Vasari, influenced by Ghiberti's incorrect testimony, would have unknowingly invented the name of a painter. If this was indeed the case, then the late date of 1381 that has traditionally been associated with the execution of the frescoes can be ignored, since the chronology is not only untenable on stylistic grounds but is also contradicted by the known circumstantial evidence, which indicates that the authorities of San Gimignano were starting to organize the decoration of the church in 1333.

Among the frescoes that fill the six bays of the right aisle of the Collegiata are the deeply expressive narratives that are for, convenience, still linked to Barna. The narrative is subdivided into three registers—the early life of Christ at the top, his ministry in the middle, and his passion below—and unfolds in a horizontal sequence from bay to bay. Equally important, however, is the vertical linkage (e.g., the first arrival of Christ in the Annunciation was planned above Christ's second arrival in the Entry into Jerusalem), which expands the overall meaning of the frescoes. Building on the example of the passion cycle from Duccio's Maestà for the cathedral in Siena, Barna also exploited changing rhythms within the narrative pace by increasing the scale of a scene, as in the monumental Crucifixion that fills two registers of a whole bay, or by allocating two compartments to a single event, as in the Entry into Jerusalem.

Problems with authorship and collaboration notwithstanding, the style of many of these scenes is characterized by elongated figures with dramatic facial expressions and agitated movements. Often sacrificing descriptive naturalism for general expressive effect, Barna's compelling works echo the art of Simone Martini, whose designs of elegant human forms punctuated with a refined sense of color were reinterpreted by Barna with an altogether sharper emotive force.

See also Duccio di Buoninsegna; Martini, Simone

FLAVIO BOGGI

Bacci, Peleo. "Il Barna o Berna, pittore della Collegiata di San Girnignano, è mai esistito?" La Balzana, 1, 1927, pp. 249-253.

Brandi, Cesare. "Barna e Giovanni d'Asciano." La Balzana, 2, 1928, p. 20.

Delogu Ventroni, S. Barna da Siena. Pisa, 1972.

Ghiberti, Lorenzo. I commentarii, ed. Lorenzo Bartoli. Florence: Giunti, 1998, p. 89.

Hofmann, Franz. Der Freskenzyklus des Neuen Testaments in der Colkgiata von San Gimignano: Ein herausragendes Beispiel italienischer Wandmalerei zur Mitte des Trecento. Munich: Scaneg, 1996.

Maginnis, Hayden B. J. Painting in the Age of Giotto: A Historical Reevaluation. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997, pp. 129-130.

Martindale, Andrew. Simone Martini: Complete Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988, pp. 55-59.

Moran, Gordon. "Is the Name of Barna an Incorrect Transcription of the Name Bartolo?" Paragone, 27 (311), 1976, pp. 76-80.

Nygren, Olga, A. Barna da Siena. Helsinki, 1963.

Vasari, Giorgio. Le vite de' più eccetlenti pittori, scultori, e architettori, ed. Gaetano Milanesi. Florence: G. C. Sanson!, 1878-1885, Vol. 1, pp. 647-651.

The composer Bartolino da Padova (fl. c. 1400) was a member of the final generation of Trecento musicians. He was born in the later fourteenth century and died in the early fifteenth. We know little of his life beyond the fact that he was a Carmelite monk, and he has sometimes been identified with one or another of the Paduan Carmelites called Bartolomeo. There are clues that he served the Cararra family of Padua at some points between 1365 and 1405, and it has been asserted that he may have spent some time (1388-1390, or after 1405) in Florence. Some of his works are said to reflect the Florentines' antagonism toward the Visconti.

Thirty-eight works, all with Italian texts, survive as Bartohni's accepted legacy. They are preserved in the famous Squarcialupi Codex, which includes his portrait. There are twenty-seven ballate and eleven madrigals, mostly in two vocal parts. Bartolini's music represents a relatively conservative continuation of the earlier Trecento tradition, with particular links to the work of Jacopo da Bologna.

See also Jacopo da Bologna; Squarcialupi Codex

JOHN W. BARKER

Goldine, Nicole. "Fra Bartolino da Padova, musicien de court." Acta Musicologica, 34, 1962, pp. 142ff.

Marrocco, William Thomas, ed. Italian Secular Music. Polyphonic Music of the Fourteenth Century, 9. Monaco: Editions de L'Oiseau-Lyre, 1974.

Petrobelli, Pierluigi. "Some Dates for Bartolino da Padova." In Studies in Music History: Essays for Oliver Strunk. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1968, pp. 85-112

Reese, Gustav. Music in the Middle Ages. New York: Norton, 1940.

Wolf, Johannes, ed. Der Squarcialupi-Codex, Pal. 87 der Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana zu Florenz. Lippstadt: Kistner and Siegel, 1955.

Bartolo ch Fredi (fl. 1353; d. Siena, 1410) was one or the most active Sienese painters of the second half of the fourteenth century. He produced numerous altarpieces for the churches of Siena and the surrounding territory, as well as major altarpieces and fresco cycles in the neighboring towns of San Gimignano, Montalcino, and Volterra. Like other Sienese artists of his time, Bartolo is known to have participated actively in Siena's political life. He not only executed major commissions for the Sienese commune—for instance, a view of Montalcino (now lost) painted in 1361 for the council chamber of the Palazzo Pubblico—but also served in civic office. In 1380, he was a member of the Opera del Duomo, the civic authority in charge of the decoration for the cathedral of Siena.

Much of the recent literature on Bartolo di Fredi has been devoted to the reconstruction of his altarpieces. As Freuler (1994) has shown, Bartolo was a painter who adapted creatively to the circumstances of his commissions, producing innovative structural and iconographic solutions. His style, which he also adapted to fit the circumstances, is generally situated between, on the one hand, the lyrical naturalism of Simone Martini and Martini's followers and, on the other hand, the highly abstracted lyricism of such great fifteenth-century Sienese painters as Giovanni di Paolo. Bartolo's narrative manner developed in close contact with the painters of Simone Martini's circle, including Lippo Memmi, who were working at San Gimignano just before the mid-fourteenth century. The Old Testament cycle that Bartolo painted in 1367 for north wall of San Gimignano's Collegiata—facing a New Testament cycle that has been variously attributed to Barna da Siena and Lippo Memmi—is remarkable for its decorative animation. In mature works like the Adoration of the Magi painted in the late 1380s for the Tolomei chapel in the cathedral of Siena, subtle harmonies of color and line are balanced with vivid characterizations to produce a highly abstracted but compelling narrative.

See also Barna da Siena; Memmi, Lippo; San Gimignano; Siena

C. JEAN CAMPBELL

Faison, Samson Lane. "Barna and Bartolo di Fredi." Art Bulletin, 14, 1932, pp. 285-315.

Freuler, Gaudenz. Bartolo di Fredi Cini: Ein Beitrag zur sienesischen Malerei des 14. Jahrhunderts. Disentis: Desertina, 1994.

Harpring, Patricia. The Sienese Trecento Painter Bartolo di Fredi. Rutherford, N.J.: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press; London: Associated University Presses, 1993.

Knapp-Fengler, Christie. "Bartolo di Fredi's Old Testament Frescoes in San Gimignano." Art Bulletin, 63, 1981, pp. 374-384.

Traldi, Rossana. "Gli affreschi di Bartolo di Fredi a Volterra e un raro combattimento apocalittico." Prospettiva, 22, 1980, pp. 67-72.

Van Os, Henk W. "Tradition and Innovation in Some Akarpieces by Bartolo di Fredi." Art Bulletin, 67, 1985, pp. 50-66.

Bartolomeo (d. 1258) studied canon and civil law in Bologna; his masters were Tancredi da Bologna in the former and Ugolino de' Presbiteri in the latter. He himself remained active in Bolognese legal circles until he was slain in Ezzolino da Romano's sack of the city.

Bartolomeo wrote several works. The earliest (c. 1234) was Brocarda, updating Damasus's expositions of legal rules with references to the Decretals of Gregory IX. He later wrote Casus (paraphrases) and Historiae (notes on biblical and historical references) for the Decretum of Gratian, as a guide to readers; and a work on legal procedure updating that of Tancredi. Bartolomeo also left two collections of legal questions. He is best-known for his revisions of Johannes Teutonicus's Ordinary Gloss on the Decretum, the version that was most often transmitted with the text well into modern times. He added references to the Gregorian Decretals and other papal decrees that were then recent, and occasionally contradicted Teutonicus.

THOMAS IZBICKI

Brundage, James. Medieval Canon Law. London: Longman, 1995.

Bartolomeo (d. 1328) studied at the University of Naples, where he received his doctorate in 1278 and taught until 1289. His father, a jurist, had served both the Hohenstaufen and the Angevins; Bartolomeo served Charles I of Anjou and his son, Charles II. The latter made Bartolomeo a leading judicial official and an envoy to popes and princes. Bartolomeo defended the right of Robert of Anjou, the son of Charles II, to succeed his father and died in Robert's service. Bartolomeo's legal works include glosses on the laws of the kingdom of Naples, some of which he had drafted, and comments on civil law.

THOMAS IZBICKI

Walter, I., and M. Piccialuti. "Bartolomeo da Capua. In Dizionario biografico degli italiani, 50 vols. Rome, 1960-, Vol. 6, pp. 697-704.

The learned Dominican Bartolomeo (1264-1347) was born in San Concordio, near Pisa; studied law and theology in Bologna and Paris; and returned to Italy to teach in the schools of the Dominican order in Rome, Florence, Arezzo, and Pistoia. Around 1312, he settled in Pisa, where he was assigned to the studium of Saint Catherine; he became its director in 1335. Bartolomeo was much admired by his contemporaries for his erudition and his prodigious memory and is most interesting to modern scholars for his prehumanistic interests and his translations.

Bartolomeo wrote or is said to have written various minor works (not all are of certain attribution): Compendium moralis philosophiae, De mernoria, De arte metrica; and comments on Virgil and Seneca. He was also the author of an interesting work called Documenta antiquorum. Its essentially pedagogic moral tone and construction are based on teachings by Thomas Aquinas, Jerome, Boethius, Isidore, and Gregory; besides these figures, there are a great number of classical Latin authors (Virgil, Cicero, Horace, Ovid, Seneca, Terence, etc.) who may constitute the artistic center of the work.

Around 1305, Bartolomeo himself translated his work into the Florentine vernacular: Ammaestramenti degli antichi (Teachings of the Ancients) was one of the most popular volgarizzamenti (vernacular translations) of the early fourteenth century because of its moderate and balanced treatment of sins, virtues, and fortune. The Italian of this translation is elegant and effective, and it prepared the the way for the two translations for which Bartolomeo is justly famous today: Sallust's Catilinario and Giugurtino, both completed by 1313. Sallust, a historian and moralist of civil life, offered themes that were appropriate for the comuni (communes), but his complex Latin had made him inaccessible to many readers before Bartolomeo's translation. Barto lomeo was fully aware of the challenge of translation (the mature prologue is proof of his preoccupation with style), and he imitated the tightness of the Latin prose successfully (and uncommonly, for medieval Tuscan tended to be verbose). At the same time, he was not afraid to take liberties when his expressive vein called for them. Thus these translations, aside from their inherent beauty and interest, provided a useful and important model for later prose works and contributed to the spread of knowledge of Rome and the classical world. During the Middle Ages, however, Bartolomeo was best known for Summa de casis conscientiae, which remained the most important confession manual for more than a century.

Bartolomeo died in Pisa.

See also Italian Prose

DAVID P. BÉNÉTEAU

Maggini, Francesco. I primi volgarizzamenti dai classici latini. Florence: Le Monnier, 1952, pp. 41-53.

Segre, Cesare. "Bartolomeo da San Concordio." In Dizionario biografico degli italiani. Rome: Istituto della Encidopedia Italiana, 1960, 6:768-770.

—, ed. Volgarizzamenti del Due e Trecento. Turin: UTET, 1953, pp. 401-445.

Bartolus (1313 or 1314-1357) was the most influential expert on civil law in Italy during the Trecento. He was born near Sassoferrato in the territory of Ancona to a prosperous rural family, was tutored by Fra Pietro d'Assisi, and entered the University of Perugia c. 1328. He studied civil law under Cino da Pistoia, absorbing both the French critical methods of legal exegesis developed at Orleans and the Bolognese forensic dialectic methods. At Bologna, Bartolus studied under Iacopo Butriga rio, Oldrado da Ponte, and Raniero Arsendi da Forli; he earned his baccalaureate degree in 1334 and his doctorate in law in 1335. Between 1336 and 1339, Bartolus served as a legal assessor for several communities, including Todi, Cagli, Macerata, and finally Pisa, where he was also appointed to the law faculty of the university in late 1339 at an annual salary of 150 gold florins. In 1343, he returned to Perugia, where he taught at the university until his death. He was made an honorary citizen of Perugia in 1348, partly in recognition of his contributions to the city and also partly in the hope that he would remain there despite lucrative offers from elsewhere. His work helped the law school at Perugia rise to rival Bologna itself as a center of legal education.

Bartolus brought to his work as a civil jurist an enormous knowledge of customary, feudal, civic, canon, and civil law; clarity, practicality, and realism in the application of legal principles; and an unflagging dedication to displaying and disseminating his scholarship—though modern scholars still dispute the authorship of several works attributed to him. He wrote commentaries on all parts of the corpus juris civilis (which fill nine of ten volumes in the 1590 edition of his works), 405 legal opinions on specific cases, and a wide range of treatises on private, public, criminal, and civil law. Through his teaching and scholarship he sought to bring the legal systems of his time into line with the code of Justinian, and to adapt that code to contemporary problems and conditions, a task begun by Cino da Pistoia. In public law especially, Bartolus endeavored to shift the field of debate and development from philosophy (or theology) to Roman law and the realities of the fourteenth century. He shared those goals with his contemporaries, the "postglossators" or "commentators." However, these other commentators tended to rely heavily on the authority of earlier glosses of civil law, weighing conflicting arguments in search of a just solution, whereas Bartolus usually began at that point but then went beyond it, often arguing with earlier interpretations and relying on other authorities.

These tendencies appear most clearly in Bartolus's treatises. In On the Government of a City he depended in part on an essentially Aristotelian analytical framework (from Politics), adding his own comments on the seventh form of government: the "monstrosity" that was contemporary Rome. In On Rivers he relied heavily on Euclid and incorporated diagrams and geometric figures to present his reasoning, a method he himself considered novel. In An Action between the Devil and the Virgin Mary Bartolus explored the procedural problems of having a female—let alone the mother of Christ the judge—serve as advocate for the plaintiff, mankind, in a suit for possession brought by the devil: an example of a teacher's whimsy highlighting serious juridical matters.

Much of Bartolus's practical legal work also involved canon law, as this system governed the political relationships of the papal states and any interactions of the church with the broader society.

The treatise On Tyranny clearly demonstrates Bartolus's concern for contemporary Italian politics as well as political theory; in this work he draws tacitly from current events in a way that anticipates the method of Machiavelli's Prince. Here Bartolus formulated the first "theory of popular sovereignty to accommodate the political reality of independent city-republics." The populus liber (free people) of the city need not recognize the higher authority of an imperial or feudal lord, having unto itself the same authority in its jurisdiction that the emperor has in his: an extension of the idea that a king is emperor in his kingdom (civitas sibi princeps). This freedom could be obtained either de iure from the emperor or de facto through usurpation and declaration. Bartolus, equating lordship with tyranny, disdained the signore and the town that accepted a signore.

Bartolus combined profound legal and jurisprudential understanding with clarity in the application of this wisdom to the problems of his own era—a combination which ensured that he would leave deep and long-lasting impression. Through his writings and his students, such as Baldus de Ubaldis, his opinions and commentaries became authoritative and remained so for more than a century, despite attacks from humanists who favored a more purely historical approach to Roman law. In the law schools of Pisa, Naples, and Padua, Bartolismo continued to shape legal science into the seventeenth century.

See also Cino da Pistoia; Giossa Ordinaria: Roman Law; Law: Roman; Perugia

JOSEPH P. BYRNE

Bartolus of Sassoferrato. Bartolus on the Conflict of Laws, trans. Joseph Henry Beale. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1914; Westport, Conn.: Hyperion, 1979.

—. Tractatus de fluminibus, seu Tyberiadis, ed. Guido Astuti. Turin: Bottega d'Erasmo, 1964.

Canning, Joseph. The Political Thought of Baldus de Ubaldis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

Cavallar, Osvaldo, et al., eds. A Grammar of Signs: Bartolo de Sassoferrato's Tract on Insignia and Coats of Arms. Berkeley: University of California, 1994.

Codices operum Bartoli a Saxoferrato recensiti. Florence: Olschki, 1971-.

Emerton, Ephraim. Humanism and Tyranny: Studies in the Italian Trecento. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1925; Gloucester, Mass.: Peter Smith, 1964.

Miceli, Augusto P. "Bartolus of Sassoferrato." Louisiana Law Review, 37, 1977, pp. 1027-1036.

Quaglioni, Diego. Politica e diritto nel Trecento italiano: il "De tyranno" di Bartolo da Sassoferrato (1314-1357), con l'edizione critica dei trattati "De Guelphis et Gebellinis." "'De regiminis civitatis," e "De tyranno. " Florence: Olschki, 1983.

Segoloni, Danilo, ed. Bartolo da Sassoferrato: Studi e documenti per il VI centenario. Milan: Giuffrè, 1962.

Sheedy, Anna Toole. Bartolus on Social Conditions in the Fourteenth Century. New York: Columbia University Press, 1942; New York: AMS, 1967.

Woolf, Cecil N. S. Bartolus of Sassoferrato: His Position in the History of Medieval Political Thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1913.

See specific place-names

See Prosdocimus de Beldemandis

Belisarius (c. 505-565), one of history's greatest generals, was born in the Balkans, but otherwise his origins are unknown. He first attracted attention while serving in the bodyguard of Emperor Justinian I and was advanced to a high command while still in his mid-twenties. He demonstrated his capacities with some brilliant successes against the Persians on the Mesopotamian frontiers, and then earned the emperor's further esteem by helping to suppress the bloody "Nika riots" that threatened Justinian's regime in 532. By this time, Belisarius was married to Antonina, a friend of Empress Theodora; Antonina's conduct was often a trial to him, but her influence at court became vital. When Justinian began an ambitious attempt to recover Roman imperial territories from barbarian regimes in the west, first by attacking the Vandal kingdom of North Africa, Belisarius was the logical choice to command the expedition. Leading a small force and displaying the bold resourcefulness for which he became famous, Belarius destroyed the Vandal forces in two lightning victories and conquered the North African realm within a few months (533-534).

Justinian next turned toward Ostrogothic Italy, and in 535 Belisarius was sent to begin recovering it. In the ensuing Gothic wars, he quickly seized Sicily and moved northward on the mainland to suppress resistance in Naples; not until he occupied Rome did he face a serious counter-effort under the new Gothic king, Witigis. In Rome, Belisarius effected the deposition of Pope Silverius, who had been elected through the influence of the Goths, replacing Silverius with Theodora's candidate, Vigilius; Belisarius also brilliantly fended off the Ostrogoths' siege of the city (537-538). For a while, his progress further north was delayed by dissension among his subordinates, but by 540 he had bottled up Witigis in the latter's capital, Ravenna. Pretending to entertain their suggestion that he become emperor in his own name, Belisarius won the surrender of the Ostrogoth leaders, but in the process he incurred Justinian's suspicion. As a result, Belisarius was recalled in disgrace to Constantinople. He was saved by his wife's influence and was returned to hard duty on the Persian frontier.

Meanwhile, the incompetence of Belarius's successors in Italy and the smoldering resentment of the remaining Ostrogoth leaders resulted in a furious renewal of war in the peninsula. Justinian then dispatched Belisarius back to Italy to resume command and conduct the war, but without forces and resources sufficient to the task. Belarius did his best, applying his old resourcefulness, and briefly recovered Rome; but he could not achieve any lasting results against the energetic Ostrogothic king, Totila. The death of Theodora in 548 deprived Belarius of his last support at court, and so, at his own request, he was recalled to Constantinople to enjoy his accumulated wealth in retirement, leaving the final reduction of Ostrogothic Italy to his eventual replacement, the general Narses.