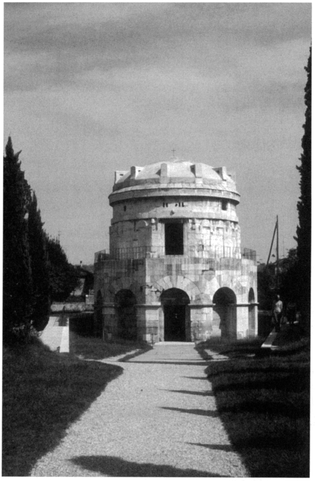

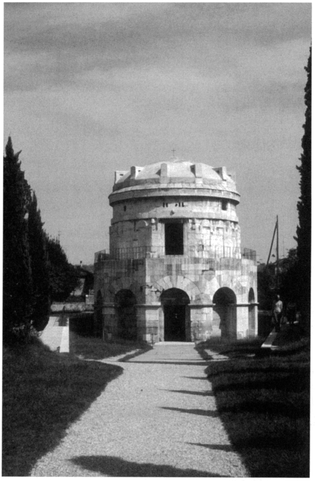

Tomb of Theodoric, Ravenna. Photograph courtesy of John W. Barker.

Taddeo Alderotti (c. 1206 or 1215-1295), a Florentine, was a physician, teacher, writer, and medical entrepreneur. He had one of the most spectacularly successful medical careers of the medieval period in Italy. His teaching—at Bologna during the height of its fame for its medical studies—was legendary, as were his learning and his great wealth. His medical writings are justly renowned, as are his opinions on philosophy and alchemy, on which he wrote a poem. He even merited mention by Dante, in the Commedia (Paradiso, 12.82-84).

Taddeo's life is known partly through municipal records of his property holdings, business transactions, loans, and investments; he also gave clues in his own works. However, the best source of his life is contained in the Liber de civitatis Florentine famosis civibus of Filippo Villani, written in the later fourteenth century, which, as Siraisi (1981) has shown, is substantiated by other sources.

Taddeo's is a classic rags-to-riches story. He appears to have been born into a Florentine family of modest means, about which little is known. He had two brothers, perhaps a sister, and, by his own testimony, an uncle who was a surgeon. In 1274, he married Adela de' Regaletti, who was from a prominent Florentine family. Taddeo and Adela had a daughter, Mina, but no son; and toward the end of his life, Taddeo petitioned the pope to legitimate his natural son, Taddeolo, so that there would be an heir for his substantial estate, worth 3,000 gold florins and 10,000 Bolognese lire.

Taddeo probably acquired his medical and philosophical education either at Florence or, more likely, at Bologna. About 1265, he began teaching medicine and logic at Bologna. This was the only place where Taddeo taught, but his students went on to teach at other Italian medical schools, and at Paris, Montpellier, and elsewhere. They include some of the most illustrious figures of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries: Bartolomeo da Varignana, Mondino de' Luizzi, Dino del Garbo, Turisanus, and many others. Taddeo's patrons included members of noble and royal households, a doge of Venice, King Enzo (the natural son of Frederick II), and perhaps Pope Honorius IV. Taddeo wrote a medical consilium for the famous surgeon and bishop Theodric of Lucca. Taddeo's writings also include commentaries on the works of Hippocrates, Galen, and Avicenna, and probably an Italian translation (from Latin) of Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics.

See also Medicine; Universities

FAYE MARIE GETZ

Siraisi, Nancy. Tadded Alderotti and His Pupils: Two Generations of Italian Medical Learning. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1981.

Taddeo di Bartolo (c. 1362 or 1363-after 28 August 1422) was the most important and innovative Sienese painter active between 1390 and 1420. He also served several times as a political official. His style, like that of other Sienese painters of the second half of the fourteenth century, was based on the tradition established by Duccio, Simone Martini, and the Lorenzetti brothers in the first half of the century. But Taddeo's particular synthesis of sumptuous Sienese decorative effects with bulky, well-modeled figures and effects of space and setting also suggests a move toward the illusionism characteristic of later developments.

Unlike most Sienese painters of the period, Taddeo had a reputation well beyond Siena; he worked for patrons from Genoa, Pisa, Montepulciano, San Gimignano, Perugia, and perhaps also Padua. At the height of his popularity he was the master of a large workshop. However, as is typical of this period, many documented works do not survive, and how many undocumented works are lost is purely a matter of conjecture. Among Taddeo's most impressive surviving works is a large, well-preserved Gothic polyptych of the Assumption and Coronation of the Virgin in the cathedral of Montepulciano. It is signed and dated 1401; in addition, and unexpectedly, the artist has included Saint Thaddeus, his patron saint, who looks out at the observer in what must be one of the earliest self-portraits.

Taddeo's frescoes in the chapel in the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena were executed in stages between 1406 and 1414. In the Last Days of the Virgin, Taddeo adds a convincing—and, again, unexpected—effect to the scene in which the apostles are summoned back from their proselytizing to bid farewelf to the Virgin before her dormition (i.e., her passing from earthly life). Here he shows foreshortened figures flying through the air, making the miraculous quality of the story more evident. The civic subjects include political virtues and Roman gods and heroes, themes planned by two Sienese intellectuals that provide yet another example of the interest in antique subjects during the Middle Ages.

See also Duccio di Buoninsegna; Lorenzetti, Pietro and Ambrogio; Martini, Simone; Siena

DAVID G. WILKINS

Solberg, Gail h. laddeo di Bartolo: A Polyptych to Reconstruct. Memphis, Tenn.: Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, 1994.

—. "Taddeo di Bartolo." In Dictionary of Art. New York: Grove's Dictionaries, 1996.

Symeonides, Sibilia. Taddeo di Bartolo. Siena: Accadeinia Senese degli Intronati, 1965.

In the battle of Taghacozzo (22 August 1268), between Conrad of Hohenstaufen (Conradin) and Charles of Anjou, Charles was the victor. This victory ensured that he would retain the kingdom of Naples and Sicily, which had been won two years previously at the battle of Benevento.

Conradin, the last male iiohenstaufen, had challenged the Angevin claim as the legitimate descendant in the direct line, through his grandfather, Frederick II, of the Norman kings. As Conradin was only sixteen years old, the effective command of his troops was undertaken by Prince Henry, who was the younger brother of the king of Castile and was senator of Rome. The battle took place at Scurcola on the Salto River, about 5 miles (8 kilometers) east of Tagliacozzo, where Henry had gone to avoid being trapped in the narrow defile of Tagliacozzo itself. Conradin probably had the numerical advantage—perhaps 6,000 soldiers to Charles's 5,000. The Angevin troops, however, were veterans and famously loyal to Charles, whereas the Hohenstaufen troops—who included German and Spanish mercenaries, Italian Ghibellines, and refugees from the Regno—were less disciplined and on the whole less interested in the outcome. After a bad start, Charles managed to divide the Hohenstaufen troops and drive them into flight. Henry was captured after the 3attle; he was to spend the next twenty-three years in prison. Shortly afterward, Conradin too was captured and executed.

Following the battle, Charles, abandoning a policy of clemency adopted after his previous victory at Benevento, viciously repressed many areas, particularly in Sicily, Apulia, and Basilicata, which had risen in sympathy with Conradin. Charles thereby incurred much hatred, which would lead to trouble later.

See also Charles I of Anjou; Conradin; Frederick II Hohenstaufen; Hohenstaufen Dynasty

CAROLA M. SMALL

Herde, Peter. "Die Schlachte bei Tagliacozzo." Zeitschrifi fur Bayerische Landesgeschichte, 25, 1962, pp. 679ff.

The Tuscan architect and sculptor Francesco Talenti (c. 1300-after 1369) is best remembered for his contribution to the building of the cathedral of Florence between 1351 and 1369. His son Simone Talenti (c. 1330-after 1383) followed in his footsteps and worked on the cathedral, as well as Or San Michele and the Loggia dei Priori. Francesco may have been the brother of Fra Jacopo Talenti (c. 1300-1362), who undertook building work at Santa Maria Novella.

In the 1350s, Francesco Talenti worked on the campanile begun by Giotto and taken over by Andrea Pisano, designing the two middle stories and the upper section of the tower shaft. During this decade he also worked on the two doorways—Porta dei Cornacchini and Porta del Campanile—in the north and south facades of the cathedral. Opinion differs as to the exact nature of Talenti's role in the final designs for the cathedral; not everyone would agree that he was responsible for the project to include a dome, first mentioned in 1357. As well as producing a model of the choir chapels (1355), Francesco Talenti made a model of the nave piers (1358); carved the capital for the first pier in the nave, assisted by his son (1358); and submitted a design of the choir in collaboration with Lapo Ghini (1366-1367).

See also Florence; Giotto di Bondone; Pisano, Andrea

FLAVIO BOGGI

Rocchi, Giuseppe, et al. Santa Maria del Fiore. Milan: Hoepli, 1988, pp. 44-50, 63-72.

Trachtenberg, M. The Campanile of Florence Cathedral: "Giotto's Tower. "New York: New York University Press, 1971, pp. 87, 109-150.

Tancred of Hauteville (d. 1041) was a petty Norman noble who held a small fief about 8 miles (12 or 13 kilometers) northeast of Coutances. For Duke Robert of Normandy, he commanded ten men-at-arms from his castle at Hauteville-la-Guichard. Tancred and his first wife, Muriella, had five sons: William, Drogo, Humphrey, Geoffrey, and Serlo. When Muriella died, Tancred married Fressenda, with whom he fathered Robert Guiscard, Mauger, William, Aubrey, Tancred, Humbert, and Roger.

Clearly, Tancred's resources were far too meager to provide much of an inheritance for such numerous progeny. Hence, William (Iron Arm), Drogo, and Humphrey set off for southern Italy c. 1035 to seek their fortune with Rainulf, who had already begun his career from the county of Aversa as his territorial base. The three brothers along with Rainulf contributed to the Lombards' victories over the Byzantines at Montemaggiore on 4 May 1041 and at Montepeloso in September 1041. Thereafter, the Normans assumed more and more control of the Lombard insurrection. After William died in 1046, the leadership of the Normans in Apulia fell to his brother Drogo, who received in 1047 full imperial investiture as duke of Apulia from Henry III (r. 1039—1056). Drogo was killed along with sixty of his followers in 1051. Norman leadership now fell to Humphrey. Along with other bands of Normans, he defeated Pope Leo IX (r. 1049-1054) and Leo's Byzantine allies at Civitate in 1053.

In 1057, Humphrey died, and Norman leadership then fell to Robert Guiscard, the first son of Tancred and Fressenda, Robert continued the conquest of Calabria, which he had begun a few years earlier on his arrival in southern Italy. He moved as far south as Reggio, which he, along with his brother Roger, besieged in 1058. These two brothers quarreled, and Roger accepted the hospitality of his brother William of Hauteville, count of the Principate, who, in the four years since his arrival in southern Italy, had conquered all the land south of Salerno. Robert, who was left to face another revolt of the Calabrians, was quick to patch up his differences with his brother Roger, and eventually the two of them would complete the conquest of Sicily and southern Italy. At the synod of Melfi in 1059, Robert Guiscard acquired the title of duke of Apulia and now had only to complete its conquest. In October 1060, Robert and his brother Mauger, count of the Capitanata, confronted the invading forces of the Byzantine emperor Constantine X Ducas (r. 1059-1067) and secured the conquest of Taranto, Brindisi, and Reggio. In 1060, Robert landed with his brother Roger in Sicily to initiate the conquest of that island. Called back to the mainland to suppress Apulian rebels, Robert completed his domination of southern Italy with the conquest of the last remaining Byzantine stronghold, the port city of Bari, in 1071. Returning to Sicily, he again assisted his brother in its conquest. In 1072, Palermo fell. Robert was then called back to southern Italy to suppress a rebellion of Norman nobles and to face the hostility of Richard of Capua and Pope Gregory VII, who excommunicated him. Robert triumphed on the battlefield, and Gregory's need for protection against Emperor Henry IV provoked Robert Guiscard to inflict his infamous devastation on the city of Rome in 1084, with the consequent flight of Gregory to Salerno. Robert died in July 1075 at age seventy.

In the meantime, Roger's campaigns in Sicily met such success that finally, by the year 1091, all the Saracens in Sicily as well as those in Malta were defeated. When Count Roger I of Sicily died in 1101, he left a well-organized and well-administered feudal state.

See also Byzantine Empire; Leo IX, Pope; Normans; Rainulf, Count of Aversa; Robert Guiscard; Roger I

ANTHONY P. VIA

Norwich, John Julius. The Other Conquest. New York: Harper and Row, 1967.

Tancred of Lecce (c. 1137-20 February 1194) was an illegitimate son of Roger, duke of Apulia, the eldest son of Roger II. Tancred was twice involved in baronial rebellions against William I, was exiled in 1161, and spent at least the last part of his enforced absence in eastern Roman (Byzantine) territory. He was recalled in 1167 or 1168, during the regency of Margaret of Navarre, and in 1169 was made count of Lecce, a small fief an the Salentine peninsula, formerly the possession of what appears to have been his mother's family. He is sometimes thought to have led the Sicilian expeditionary force in Egypt in 1174. By 1176, he was grand constable and master justiciar for Apulia and Terra di Lavoro, a post he continued to hold at least until 1187- He commanded the fleet in William II's failed attempt to take Constantinople in 1185- In the succession crisis of late 1189, he was the candidate of a faction in the central government led by the vice-chancellor, Matthew of Salerno. In December 1189, Tancred was elected king by an assembly of curial magnates who were opposed to the prospect of rule by William's announced heir Constance, or by her German husband, the future western emperor Henry VI. After obtaining the support;)f the papacy, Tancred was crowned on 18 January 1190.

Tancred was an effective ruler in an insecure position. He put down an Arab-Islamic revolt at the outset of his reign; gained internal support by means of appointments and concessions; suppressed a rival candidate, Roger of Andria, for the throne; and through a combination of diplomacy, military success, and shows of force managed to fend off Henry's major invasion of 1191 and other attempts from 1190 onward to bring the kingdom within the empire. Prominent in this effort were Tancred's brother-in-law and military commander on the mainland, Richard of Acerra; and his admiral of the fleet, Margaritus of Brindisi, a holdover from the previous reign. Like Tancred, Richard had learned firsthand during William II's disastrous invasion of Greece that a new but energetic regime fighting on its own soil could defeat a large enemy army seeking to overthrow it. Margaritus was instrumental in carrying out their strategy, particularly in the defense of Naples in 1191. At Naples, by keeping open its maritime supply lines and winning a naval victory over Henry's Pisan allies, Margaritus forced Henry to abandon his lengthy siege of this crucial strongpoint, and with it his very expensive campaign of that year.

Tancred was over fifty—and thus elderly by contemporary standards—when he came to power. He provided for the succession in 1192 by having his son Roger also crowned king, as Roger III. In the same year he negotiated an alliance with Isaac II Angelus, the Roman emperor of the east, an accord sealed by a marriage between Isaac's daughter Irene and the young Roger III. Tancred also allied himself with Richard I of England and with the papacy. But in 1193, once Richard had become the prisoner of Henry VI, this was a coalition of the weak and the disabled. Roger Ill's untimely death on 24 December left only his brother William, still a child, in line to succeed. When Tancred himself died less than two months later, the way was open for Henry's successful invasion of 1194 (funded from the proceeds of Richard's enormous ransom).

Roger and Tancred were both buried in Palermo's then new cathedral. There, on Henry's orders, their bodies were later stripped of crowns and other regalia (when the bodies were examined during a reconstruction in 1767, the remains, since lost, were said to have been headless). As Tancred's official acts were declared invalid by the new regime, the surviving documentation for his reign is scant. Peter of Eboli's illustrated Liber ad honorem Augusti lampoons Tancred memorably from a pro-Staufen perspective. Tancred's predecessors on the throne are known for their artistically important buildings in or near the capital; Tancred's own monument, more modest but still impressive, is the convent church of saints Nicholas and Cataldus at Lecce, completed in 1180. This edifice retains much of its original form, and it preserves, especially in its two ornamental portals with their dedicatory inscriptions in Leonine Latin verse, the memory of its donor when he was count and not yet king.

See also Normans; Peter of Eboli; Roger II; William I; William II

JOHN B. DILLON

Zielinski, Herbert, ed. Tancredi et Willelmi III. regum diplomata. Codex Diplomaticus Regni Siciliae, Series 1(5). Cologne: Bohlau, 1982.

Clementi, Dione. "The Circumstances of Count Tancred's Accession to the Kingdom of Sicily, the Duchy of Apulia, and the Principality of Capua." In Mélanges Antonio Marongiù. Brussels: Éditions de la Librairie Encyclopédique, 1968, pp. 57-80.

Cuozzo, Errico. "Corona, contee, e nobiltà feudale nel regno di Sicilia: AH'indomani dell'elezione di re Tancredi d'Altavilla." In Medioevo Mezzogiorno Mediterraneo: Studi in onore di Mario Del Treppo, ed. Gabriella Rossetti and Giovanni Vitolo, Vol. 1. Europa Mediterranea. Quaderni, 12. Naples: Liguori, 2000, pp. 249-265.

Gentile Messina, Renata. "In margine ad un accordo matrimoniale tra Bizantini e Normanni in Sicilia." In Alpheios: Rapporti storici e letterari fra Sicilia e Grecia (IX—XIX sec.), ed. Giuseppe Spadaro. L'Armilla, 4. Caltanissetta: Lussografia, 1998, pp. 103-118.

Jamison, Evelyn. Admiral Eugenius of Sicily: His Life and Work and the Authorship of the "Epistola ad Petrurn" and the "Historia Hugonis Falcandi Siculi." London: Oxford University Press for the British Academy, 1957. (See especially pp. 80-102.)

Matthew, Donald. The Norman Kingdom of Sicily. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992, pp. 287-295.

Pellegrino, Bruno, and Benedetto Vetere, eds. II tempio di Tancredi: II monastero dei Santi Niccolò e Cataldo in Lecce. Milan: Silvana, 1996.

Riesinger, Christoph. Tankred von Lecce: Normannischer Konig von Sizilien. Kölner Historische Abhandlungen, 38. Cologne: Böhlau, 1992.

Tancredi (d. 1236) studied canon law in Bologna with Laurentius Hispanus and Johannes Galensis. He also studied civil law with Azo. He commented on the Breviarium decretalium of Bernardo da Pavia; on a collection of Innocent Ill's decretals by Pietro da Benevento (1210); and on a collection by Johannes Galensis filling the gap between those two (1210—1215). Tancredi wrote a widely known guide to legal procedure (c. 1218), basing his work on earlier texts. This text remained popular until the Speculum judiciale of Guillelmus Durantis the Elder appeared in 1271. Tancredi became a canon of Bologna and served as the city's archdeacon until his death.

See also Law: Canon

THOMAS IZBICKI

Brundage, James. Medieval Canon Law. London: Longman, 1995.

Clarence Smith, J. A. Medieval Law Teachers and Writers Civilian and Canonist. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 1975.

Friedberg, Emil, ed. Quinque compilationes antiquae. Leipzig: Tauchnitz, 1882.

The Tavola ritonda (Round Table), one of the earliest examples of vernacular prose narrative, composed c. 1320-1340, survives in eight manuscripts, indicating a healthy circulation for such a text. The anonymous author freely drew on several French sources—the prose Tristan, Thomas's Tristan, the Roman de Lancelot, Meliadus by Rusticiano da Pisa, and the Tristano Riccardiano. The originality in selection and the arrangement of material combined with several invented episodes make the Tavola ritonda the most elaborate and innovative of the Italian Arthurian romances. Although criticism on this text is not extensive, the varied, even conflicting, interpretations of crucial themes, episodes, and characterizations testify to its complexity.

The Tuscan author reworked his source material—often filled with fabulous adventures—to appeal to the tastes of his pragmatic merchant-class readers. By rearranging and interspersing parallel scenes, he idealizes Tristan as both a better knight and a better lover than Lancelot. The adulterous aspects of Tristan and Isolde's passion are minimized to show their love as more pure and "loyal" than that of Lancelot and Guinivere, indeed as almost divine. This favorable portrayal of adulterous lovers may be a direct response to Dante's condemnation of carnal lust in Inferno 5.

Although Arthurian romances typically have love as "heir theme, in this redaction feats of arms are given equal importance. Yet this is a new brand of chivalry that domesticates the errant knight by channeling his energies into the defense of urban securitas, an ethos more in line with the civic ideals of communal Italy. There is less gratuitous jousting and more purposeful combat than in earlier versions. In addition, diplomacy can be as efficacious as physical prowess (a portrayal that echoes contemporary Florentine military history). Certain critics have pointed to a "social theme," also consonant with communal ethics: an individual's actions can have an impact, for good or ill, on his entire society.

See also Arthurian Material in Italy; Lancelot; Tristan

GLORIA ALLAIRE

La tavola ritonda, o L'istoria di Tristano, 2 vols., ed. Filippo-Luigi Polidori. Collezione di Opere Inedite o Rare dei Primi Tre Secoli della Lingua, 8-9. Bologna: Romagnoli, 1864-1866. (Completed by Luciano Banchi.)

Tristan and the Round Table: A Translation of La tavola Ritonda, trans. Anne Shaver. Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies, 28. Bingham ton, N.Y.: Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies, 1983.

II Tristano panciatichiano, ed. and trans. Gloria Allaire. Arthurian Archives: Italian Literature, 1. Woodbridge: D. S. Brewer, 2002.

Cardini, Franco. "Concetto di cavalleria e mentalità cavalleresca nei romanzi e nei cantari fiorentini." In I ceti dirigenti nella Toscana tardo comunale: Atti del III Convegno, Firenze, 5-7 dicembre 1980. Florence: Papafava, 1983, pp. 157-192.

Delcorno Branca, Daniela. I romanzi italiani di Tristano e la Tavola ritonda. Pubblicazioni della Facoltà di Lettere e Filosofia, Università di Padova, 45. Florence: Olschki, 1968.

Hoffman, Donald L. "Radix Amoris: The Tavola ritonda and Its Response to Dante's Paolo and Francesca." In Tristan and Isolde: A Casebook, ed. Joan Tasker Grimbert. Arthurian Characters and Themes, 2. New York: Garland, 1995, pp. 207-222.

Kleinhenz, Christopher. "Tristan in Italy: The Death or Rebirth of a Legend." Studies in Medieval Culture, 5, 1975, pp. 145-158.

Tasker Grimbert, Joan. "Translating Tristan-Love from the Prose Tristan to the Tavola ritonda." Romance Languages Annual, 6, 1994, pp. 92-97.

See Revenues

The Florentine poet Pieraccio Teldadi (first half of the fourteenth century) wrote in both the amorous-courtly and the comic styles. He wrote forty sonnets and one tenzone, all transmitted by a single manuscript, Vaticano Latino 3213.

Although ledaldi wrote six sonnets following the aulic (courtly) tradition, he is best-known as a comic poet. The comic themes he used most often were condemnations of marriage, wry comments on the overinflated value of money in contemporary society, and lamentations against poverty. He also wrote a series of political sonnets as an impassioned Guelf, two of which are directed against Mastino II della Scala. Moral sonnets that he wrote in his old age include diatribes against gambling; warnings to lawyers, judges, and notaries against corruption; and accusations that society is pursuing sensual pleasures rather than serving God. In religious sonnets from the same period, Tedaldi confesses his own sins and prays for forgiveness. There are also sonnets concerning his blindness, which he considered a divine punishment for past sins. The tenzone, addressed to his son, Bindo, accuses Bindo of never taking the time to write his father a letter. Among Tedaldi's well-known poems, Qualunque voi super far un sonetto describes how to write a good sonnet, and Sonetto pien di doglia, iscapigliato is a planctus (lament) for the death of Dante, whom Tedaldi calls "our sweet master."

See also Italian Poetry: Comic; Tenzone

JOAN H. LEVIN

Marti, Mario. Poeti giocosi del tempo di Dante. Milan: Rizzoli, 1956, pp. 715-758.

Massera, Aldo Francesco. Sonetti burlescbi e realistici dei primi due secoli. Bari: Laterza, 1920. (See also rev. ed., ed. Luigi Russo, 1940, Vol. 2, pp. 35-58.)

Sapegno, Natalino. Poeti minori del Trecento. Milan and Naples: Ricciardi, 1952, pp. 317-329.

Vitale, Maurizio. Rimatori comico-realtstici. Turin: UTET, 1956, pp. 691-749. (Reprint, 1976.)

Messina, Michele. "Tedaldi, Pieraccio." In Enciclopedia dantesca, vol, 5, Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 1970-1978 pp. 535-536.

Petrocchi, Giorgio. "I poeti realisti." In Le origini e il Duecento, ed. Emilio Cecclii and Natalino Sapegno. Storia della Letteratura Italiana, 1. Milan: Garzanti, 1965; rpt. 1979, 575-607.

The battle of Teginae (Busta Gallorum, 552), the last battle of King Totila, doomed the Ostrogoths' resistance to the eastern Roman armies under Narses, Before the arrival of Narses in Italy (551), neither the Goths nor the eastern Romans had been able to field an army large enough to gain a decisive advantage. Totila knew that the longer he waited, the stronger Narses would become, and so he hastened to attack immediately. The battle pitted a Roman force drawn up in mixed array against Gothic cavalry backed by Gothic infantry. Totila, seeing that his force was greatly outnumbered, delayed, while an additional 2,000 men assembled from nearby camps. He guided his horse to the middle ground between the warring armies and wheeled his mount in a circle—first in one direction, then in the other, tossing his javelin high in the air and catching it. Surely this dance evoked something noble and warlike from Gothic tradition. The Gothic cavalry struck the first blow but was soon pushed back into the protection of the Gothic infantry. There, among the rank and file, without his golden armor, Totila died along with some 6,000 others.

The survivors fled and rallied under their last king, Teias; but at Mons Lactarius near Naples later in 552, Teias fell. In August 554, Justinian issued his pragmatic sanction for the governing of reconquered Italy.

See also Gothic Wars; Justinian I; Narses; Ostrogoths; Pragmatic Sanction; Totila

THOMAS S. BURNS

See Military Orders in Italy

Like other early vernacular lyric forms brought to Sicily and to northern Italy by thirteenth-century troubadours, the tenzone probably developed from the Occitan tenso, or poetic debate. The related contrasto evolved from a medieval Latin analogue that contained a philosophical disputation within a single composition by one author, alternating voices stylistically or structurally between strophes; but the typical tenzone consists of at least two separate microtexts (normally sonnets; rarely canzoni) written by individual poets who are sometimes joined by additional voices. Topics include love, poetics, and politics.

Virtually every poet participated in the huge production of tenzoni in the second half of the thirteenth century: Monte Andrea da Firenze initiated a long political debate with various poets; Bonagiunta da Lucca and Guido Guinizzelli participated in a famous debate; Dante Alighieri exchanged poems with Dante da Maiano and with Cino da Pistoia. Several extant tenzoni included anonymous women "respondents." A particularly biting six-sonnet tenzone between the young Dante and his future wife's relative Forese Donati (d. 1296) has been a source of unending controversy: despite codicological, lexical, and textual evidence, many scholars cannot accept the possibility that the great poet could have entered into a scurrilous debate.

Since the tenzone was a small but ordered grouping of textually related poetic compositions, it may be considered a forerunner of the poetry book. The tenzone was recognized as an independent genre by contemporary copyists, who often labeled it as such and even numbered the related texts in their manuscripts.

See also Italian Poetry: Lyric; Italian Prosody; Sonnet

GLORIA ALLAIRF.

Alfie, Fabian. "For Want of a Nail: The Guerri-Lanza-Cursietti Argument Regarding the Tenzone." Dante Studies, 116, 1998, pp. 141-159.

Aliberti, Domenico B. "La concezione dell'amore nella tenzone poetica tra Chiaro Davanzati e Pacino di Ser Filippo Angiulieri." Italica, 67, 1990, pp. 319-334.

Barbi, Michele. "La tenzone di Dante con Forese." Studi Danteschi, 9, 1924, pp. 5-149.

Bartlett, Elizabeth, and Antonio Illiano. "Dante's 'Tenzone.' " Italica, 44, 1967, pp. 282-290.

Santangelo, Salvatore, Le tenzoni poetiche nella letteratura delle origini. Biblioteca dell'Archivum Romanicum, Series 1, Storia-Letteratura-Paleografia, 9. Geneva: Olschki, 1928.

Stauble, Antonio. "La tenzone di Dante con Forese Donati." Letture Classensi, 24, 1995, pp. 151-170.

Little is known about the life of Terence (Publius Terentius Afer, c. 186 or 185-c. 159 B.C.). He was born in Carthage, and some scholars argue for an earlier birth date than 185 B.C. He came to Rome, perhaps as a slave; there, he received support from noble patrons.

Six of Terence's comedies have been transmitted to us: Andria, Hecyra (The Mother-in-Law), Heautontimoroumenos (The Self-Punisher), Eunuchus (Terence's greatest commercial success), Phormio, and Adelphoe (The Brothers). The plots of these plays are influenced by Attic "new comedy," but Terence's attention to character development represents an innovation in the comic genre. During antiquity, Terence's work was considered dull, lacking in verbal invention and comic ingeniousness, but Terence's focus on psychology provides a point of interest not found in the plays of his contemporaries.

In the fourth century the grammarian Donatus composed an extensive commentary on Terence's plays, and in the Middle Ages Terence was a hugely influential school author. His lucid Latin and didactic tendencies made him very appealing to a Christian readership; his plays were commended for their ethical messages. His central role in medieval school curricula allowed a wide dissemination of his work. In the tenth century Terence influenced the dramatic efforts of the German nun Hrosvitha (Hrotsvitha, Hroswita) of Gandersheim; and in the twelfth century a genre of pseudo-Terentian satirical dramas flourished.

While Dante aliludes in a general way to Terence's comedies, there is no concrete evidence that he knew the plays in detail. An inaccurate reference in Inferno 18 to the courtesan Thai's, a character in Eunuchus, reveals that Dante's knowledge of the play was derived from Cicero's De amicitia rather than from Eunuchus itself. Beginning with Boccaccio and continuing with Petrarch, however, Terence's plays were copied, studied, and understood, as is evidenced by annotations on a Florentine manuscript of Terence's comedies in Boccaccio's hand.

See also Theater

JESSICA LEVENSTEIN

Kauer, Robert, and Wallace M. Lindsay, rev. Otto Skutsch. Oxford: Clarendon, 1958. (Originally published 1926.)

Marouzeau, Jules. 3 vols. Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 1942-1949.

Sargeaunt, John. Loeb Classical Library. London: Heinemann, 1912.

Brothers, Anthony J. Heautontimoroumenos. Warminster: Aris and Phillips, 1988.

Gratwick, A. S. Adelpboe. Warminster: Aris and Phillips, 1987.

Ireland, S. Hecyra. Warminster: Aris and Phillips, 1990.

Martin, Ronald H. Adelphoe, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976.

Shipp, George P. Andria. Salem, N.H.: Ayer, 1984. (Originally published 1960.)

Forehand, Walter E. Terence. Boston: Twayne, 1985.

Goldberg, Sander M. Understanding Terence. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1986.

Grant, John N. "Taide in Inferno 18 and Terence Eunuchus 937." Quaderni d'ltalianistica, 15, 1994, pp. 151-155.

Norwood, Gilbert. The Art of Terence. Oxford: Blackweil, 1923.

Paratore, Ettore. "Terenzio." In Enciclopedia dantesca, ed. Umberto Bosco. Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 1970-1978, Vol. 5, pp. 569-570.

The Placiti cassinesi, also known as the Placiti campani, are a collection of tenth-century juridical documents preserved in the archives of the abbey of Monte Cassino and still in the possession of the abbey. They are generally said to contain the first extant manifestations of intentional writing in the volgare on the Italian peninsula. Each document consists of a body of text in Latin, with single sentences of a formulaic nature, in what appears to be a rather faithful rendering of the language of the time and place. The purpose of the documents is to establish disputed ownership of lands.

The earliest document was drawn up in Capua in March 960 and is thus widely known as the placito capuano, or alternatively as the placito d'Arechisi, after the judge in charge of the proceedings. The case pits the abbot of Monte Cassino against a private citizen named Rodelgrimo, who claims to have inherited lands that the abbot claims have been the property of Monte Cassino for thirty years. With neither side in possession of documentation of ownership, the judge orders the abbot to produce three witnesses, each of whom then repeats the words Sao ko kelle terre per kelle fini que ki contene, trenta anni le possette parte S{an)c{t)i Benedicti and swears that this is true.

I he placito of Sessa, from March 963, reports a similar case between the abbot of the monastery of San Salvatore and a citizen named Gualfrid. Here, however, the abbot is able to produce documentation showing that the land was in part purchased, in part received as a donation, from a certain Pergoaldo, Three witnesses are then called on to testify that this previous owner had been in legitimate possession, which they do by reciting Sao cco kelle terrep{er) kelle fini que tebe monstrai P(er)goaldo foro que ki contene et trenta anni le possette.

Two further documents deal with land disputes in the district of Teano. The earlier of these two, dated 26 July 963, is known as the Memoratorium of Teano-, it contains the oath Kella terra p{er) kellefini q{ue) bobe mostrai S{an)c{t)e Marie è et trenta anni la posset parte S(an)c(t)e Marie. The later of the two, the Placito of Teano, has four repetitions, one for each witness, of words nearly identical to those of the oath taken at Sessa: Sao cco kelle terre p(er) kelle fini que tebe mostrai trenta anni le possette parte S{an)c{t)e Marie.

I he prime interest of these documents is both historical and linguistic. Some scholars suspect that the disputes may have been preventive measures brought against straw men, for the purpose of establishing ownership of lands whose status could have been subject to genuine dispute in the absence of firm legal documentation. In this view, the use of popular language for the oaths would have served to make the essential information clear to any reader. Other scholars argue that certificates issued just a few years earlier by competent local authorities precluded any need for such legal reassurance, and the fact that only these documents contain testimony in the volgare may be due to their being originals. Others, which survive only in copies, have very similar oaths, invariably in Latin, arguably the result of emendation by copyists: e.g., Scio quia ille terreper illos fines et mensuras quas Paidefrit comiti monstravimus per XXXa annos possedit pars Sancti Vincencii (sworn in 954, also before Arechisi).

I he Latin that frames and introduces the testimonies in volgare is unremarkably typical of practical papers of the time, lacking the accurate classicizing tone of highly trained authorship, and penetrated by localisms in Latinized form. It was once believed that the vernacular of the oaths was a conscious attempt at a refined version of the speech of the area, but various scholars have shown that they are almost certainly very accurate phonemic renderings of popular speech, with occasional phonetic detail, and few spurious Latinisms. Consider, for example, Sao cco kelle terre ("I know that those lands"). Although today dialects in Campania normally have a reflex of sapio ("I know") along the lines of saccio, the form sao ("I know," Italian so) is still common in southern Italy (along with, e.g.,fao, "I make" or "I do"). Co (also spelled ko, and derived from quod) is still widespread in the south; and the simple [k], rather than [kw] (Italian quelle) of kelle (derived from eccu illae, "those") parallels modern Neapolitan kidde (further evolved in the raising of [e] to [i] and the delateralization /ll/, from /dd/). These and other features appear to guarantee that the language of the placiti is genuine and thus is a valuable early documentation of evolved Romance speech.

See also Language, Italian: History and Development

THOMAS D. CRAVENS

The Ritmo laurenziano is so called because it is contained in the last folio of a codex in the Laurentian Library in Florence; it is also known variously as the Ritmo giullaresco toscano, the Cantilena monorima, or the Cantilena di ungiullare toscano. It is generally considered the oldest surviving Italian poetic composition with literary pretensions. The text is of uncertain date but is in a hand that suggests the late twelfth century or the early thirteenth century; the identity of the author is unknown.

The Ritmo laurenziano consists of twenty double octosyl-lables. The allusions made (apparently to the Physiologus and to the Disricba Catonis) and the poetic structure (recalling the Provencal Sancta Fides) reveal some learning on the part of the author. The ends, however, are practical: a giullare spares no hyperbole to sing the praises of a bishop (Villano, of Pisa, according to some scholars, but the bishop of Iesi now appears more likely), in hopes that the bishop will see fit to present him with the gift of a fine white-footed horse, which he will then display to the bishop of Volterra, Galgano. Though it was once thought that the language reflected an eastern Tuscan origin, this opinion has been shown to have little foundation. Until recently, parts of the text remained obscure. Lacunae and illegible script in the manuscript itself, along with puzzling lexical items, left the way open for numerous suggested readings of crucial passages. Castellan! (1986) made definitive corrections of earlier scholars' hypotheses, including the probable identification of the bishop to whom the work is addressed: lo vescovo senato, in which senato was once thought to have been a Tuscanized borrowing of a precursor of French sent ("wise"), is much more plausibly local usage deriving directly from Latin aesinas, producing "of Iesi." Castellani's informed philological analysis suggests that regarding origins all we can say with certainty is that the linguistic character of the text is genuinely Tuscan; also, both linguistic and nonlinguistic evidence hints that the author may have come from the diocese of Volterra.

See also Italian Prosody; Language, Italian: History and Development

THOMAS D. CRAVENS

Castellani, Arrigo. "II Ritmo laurenziano." Studi Linguistici Italiani, 12, 1986, pp. 182-216.

See Fustians; Silk in Italy; Wool Industry in Italy

Theater was an essential part of medieval life and consequently encompassed more than today's restricted notion. However, the practice of going to the theater as a paid public event, purely for the purpose of entertainment, lapsed during the Middle Ages, even though formally structured plays with costumed actors, prepared speeches, scene changes, and music had been performed in ancient Roman theaters, and the ruins of these Roman edifices survived in medieval Italy.

Forerunners of popular theater in Italy were the numerous public spectacles, ceremonies, propitiatory processions of spiritual groups such as the flagellants, and even races, games, and athletic contests which developed distinct regional variations. To celebrate the rites of spring, rural Tuscan towns held popular dramas known by different names (giostre near Pistoia, bruscelli near Siena, maggi in Pisa and Lucca). Self-conscious displays of power and prestige by individual families or political groups were prevalent in the late fourteenth century and the fifteenth century and constituted a kind of unofficial theater. Mummers and maskers in France and England had their parallel in the elaborate carnival parades and costumes of late medieval Florence and Venice. In Medici Florence, wagons (carri) bearing tableaux of costumed figures accompanied by music and singing often used mythological themes. Lorenzo de' Medici (il Magnifico) himself contributed texts for several carnival songs and is even credited with developing this genre.

Orally performed epics ana cantari are a secular strain that fed into the development of theater in Italy. The giullari, later called cantastorie or canterini, would have used gestures, movements, simple sound effects, and a range of vocal inflections to enhance their texts, performed with the accompaniment of stringed instruments. Performers availed themselves of a raised platform such as a stone bench or staircase to make themselves more visible and to project their voices better. We can surmise this from one Italian noun for singers of tales: cantimbanchi, literally, "songs on the benches." These were extremely popular in Bologna, Florence, and Perugia, as documents indicate. Elements of this epic performance style survived in nineteenth century and early twentieth-century street theaters of Sicily and Naples.

The religious strain of early theater has left more written traces. Mystery plays were performed throughout Europe to illustrate Christian stories and principles, and Italy was no exception. The combination of text, music, costumes, sounds, and simple props or backdrops had the powerful effect of heightening spirituality. Subjects included Old and New Testament stories, especially the more dramatic episodes; saints' lives; and other sacred legends. These could have been simple (though costumed) tableaux "acted" by priests during a mass, or longer stories that were actually performed. Luoghi deputati—multiple sets used in succession—were used for religious dramas and were paralleled in the visual arts: frescoes and altarpieces often depicted a series of events in the life of Christ or a saint, each action in its own separate section or panel. In fact, a modern word for the formal stage preserves this early sense: palcoscenico, "scenic box."

Extant documentation indicates that religious plays were widespread throughout the peninsula and in Sicily. Since there were no established commercial theater buildings, plays were performed within monasteries or convents, inside churches for special festivals, or in public squares. Without a clear stage separation from the audience seating area, such "interactive" dramas resembled modern experimental theater: actors could enter through the crowd, and audience members would have been physically much closer to the drama. The grotesque devils in Dante's Commedia (Inferno, 21-22) preserve a glimpse of the frantic tragicomic activities of demons issuing from "hell's mouth," a frequent element in the intermezzi of mystery plays.

The concept of plays for didactic purposes developed from laude, vernacular hymns of praise. These laude were of Umbrian origin and were used by Saint Francis and his followers in the early thirteenth century; they were sung or chanted and could also be accompanied by dancing as a popular expression of religious zeal. The lauda "Lament of the Virgin Mary" by Jacopone da Todi—which is in effect a mini-drama—is a moving dialogue between the Virgin and her son, who is dying on the cross. Each of the alternating stanzas represents the "speech" of a "character." Early laude survive from Perugia, Assisi, Gubbio, Orvieto, and Aquila.

Written scripts for many religious spectacles have survived, and archival documents and records of payments further indicate what kinds of theatrical activities took place. In the urban centers of late medieval Italy, civic and religious institutions inevitably came into contact. Their functions intermingled in a complex symbiosis, with public spaces being used for sacred displays, sacred spaces being invaded by individual propaganda, and financial support often deriving more from political opportunism than from charitable motivations. Churches and lay confraternities organized special dramatic spectacles for important feast days such as the Annunciation, Epiphany, and Ascension day. Companies of artisans and laymen dedicated themselves to these annual representations, just as today certain charitable or civic groups sponsor parades or local festivals in their communities. Scenery, lighting effects, and stage machinery became quite elaborate.

The sacra rappresentazione, a Tuscan phenomenon that flourished in the fifteenth century, was essentially popular in nature. Feo Beicari (1410-1484, Florence) is the best-known author in this genre. His surviving sacred plays, written in octaves, had as their themes Abraham and Isaac, the Annunciation, the life of the blessed Giovanni Colombini, and Saint John the Baptist in the desert. A short San Panuzio is also attributed to him. Lorenzo de' Medici produced a single dramatic work, the Sacra rappresentazione di Santi Giovanni e Paolo. Such plays demonstrate a certain relationship to the epic in their meter, tone, and style. Their form was free, with no unity of time, place, or action. A closing epilogue provided the moral.

By the late fifteenth century, with the influence of humanism, sacre rappresentazioni were including more and more secular elements. An important contribution of humanism with respect to the history of theater in Italy was the rediscovery and actual performance of old Roman plays by Terence and Plautus, especially in the north, at Ferrara and Florence. Authors of the time imitated these ancient plays; for example, Machiavelli's La Clizia, performed in 1525, was based on Plautus's Casina.

See also Cantare; Giullari

GLORIA ALLAIRE

Barr, Cyrilla, The Monophonic Lauda and the Lay Religious Confraternities of Tuscany and Umbria in the Late Middle Ages. Early Drama, Art, and Music Monograph Series, 10. Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publications, Western Michigan University, 1988. —. "A Renaissance Artist in the Service of a Singing Confraternity." In Life and Death in Fifteenth-Century Florence, ed. Marcel Tetel, Ronald G. Witt, and Rona Goffen. Duke Monographs in Medieval and Renaissance Studies. 10. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1989, pp. 105-119.

Belcari, Feo. Sacre rappresentazioni e laude, ed. Onorato Allocco-Castellino. Collezione di Classici Italiani con Note, 13. Turin: UTET, 1920.

Cioni, Alfredo. Bibliografia. delle sacre rappresentazioni. Biblioteca. Bibliografica Italica, 22. Florence: Sansoni Antiquariato, 1961.

Sacre rappresentazioni, ed. Luigi Banfi. Teatro del Quattrocento, 1. Turin: UTET, 1997.

Sacre rappresentazioni manoscritte e a stampa conservate nella Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze: Inventario, ed. Anna Maria Testaverde and Anna Maria Evangelista. Inventari e Cataloghi Toscani, 25. Milan: Giunta Regionale Toscana and Editrice Bibliografica, 1988.

Sacre rappresentazioni per le Fraternite d'Orvieto nel cod. Vittorio Emanuele 528, ed. A[nnibale] T[ennerone]. Bollettino della R. Deputazione di Storia Patria per l'Umbria, Appendix 5. Perugia: R. Deputazione di Storia Patria, 1916.

Vattasso, Marco. Per la storia del dramma sacro in Italia. Studi e Testi, 10. Rome: Tipografia Vaticana, 1903.

Theodahad (d. 536, r. 534-536) was a king of the Ostrogoths. He was the son of Amalafrida, nephew of Theodoric, brother of Amalaberga, and father of Theudegisclus and Theodenantha. He led the life of a rich Roman recluse, vir spectabilis and later vir inlustris, devoting his leisure to literature, especially Plato. His wealth included lands belonging to the royal patrimonium and estates inherited from his mother (d. 527) but did not satisfy his avarice: before becoming king, he illegally evicted poor Gothic landowners and sometimes enslaved them, thwarted only by their appeals to his predecessor, King Athalaric.

The death of Athalaric (534) left I heodahad, the senior male member of the Amali family, in a peculiar and uncomfortable position. His cousin Amalasuntha, as a part of her program to frustrate the nobles who were opposed to her, asked him to succeed her son Athalaric in name only and actually to be a co-ruler with her. This proved unacceptable to Theodahad and the Gothic nobility. Amalasuntha was exiled and killed (535). She had, however, opened negotiations with Emperor Justinian I, and her death provided a pretext for him to commit his troops. Theodahad tried to explain himself to the emperor and gain Justinian's support, apparently even offering to trade his personal estates for a comfortable life in Constantinople. However, his offer was rejected and his explanations were dismissed. War came swiftly, and no organized opposition to Justinian's forces emerged. The nobility rose and raised one of their own, Witigis, as king (536).

Theodahad was executed while in flight to Ravenna. He was the last Amalian king and the first barbarian ever to put his own portrait on a Roman coin.

See also Amalasuntha; Gothic Wars; Justinian I; Ostrogoths; Witigis

THOMAS S. BURNS

Theodora (c. 500-548) became empress of Byzantium in 527. She had been born in poverty and had spent her youth as a notoriously virtuosic courtesan in Constantinople. But she reformed, and her cleverness and strong personality attracted the young Justinian, who made her his wife and, on his ascent to the throne as Justinian I, his consort.

Although Theodora differed with Justinian on theology and, as a strong adherent of Monophysitism, sometimes worked against his policies, she was his invaluable ally and counselor. Her advice helped him rescue his throne during the Nika riots (532), and her death from cancer in 548 was a grievous blow to him personally and politically.

Theordora had risen from the dregs of society and never felt totally secure on her throne; she intrigued constantly to ward off any challenge she saw to her husband or to her own standing with him. Thus, it is said, Theodora became jealous of the Ostrogothic queen of Italy, Amalasuntha, who was famous for cleverness and beauty, and—anxious lest this woman come to the capital and attract Justinian—conspired to have her murdered as a part of the dynastic tangles of the Ostrogothic court. Theodora's support of the Monophysites was played on by the Roman legate Vigilius, who promised her his aid in return for her influence in having him made pope (537). However, Vigilius found it impossible to keep his promise, and Theodora became his implacable foe. At her urging, Justinian had Vigilius abducted and brought to Constantinople to be coerced into supporting religious policies that Theodora had helped frame. Vigilius's degradation was Theodora's last triumph before her death.

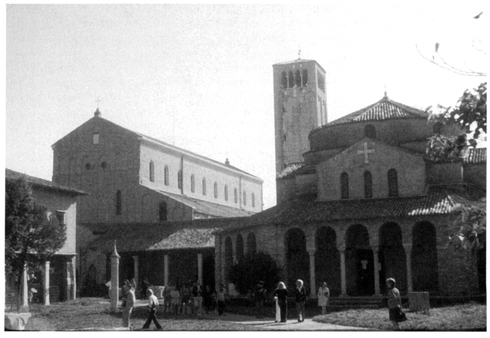

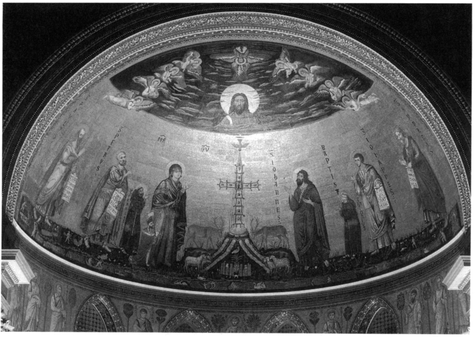

Several portrait busts surviving from this period have been identified as Theodora, notably one that is now in the Castello Sforzesco in Milan. Even more striking is her austere portrayal, together with her retinue, in a famous mosaic panel in the church of San Vitale in Ravenna. Fired by the sensational account given of her by the historian Procopius, artists and writers of modern times have continued to be fascinated by her image: she has been the fanciful subject of an opera by Donizetti, a play by Sardou, numerous novels, and at least one (Italian) movie.

See also Amalasuntha; Justinian I; Monophysitism; Procopius of Caesarea; Vigilius, Pope

JOHN W. BARKER

Bridge, Antony. Theodora: Portrait in a Byzantine Landscape. London: Cassell, 1978.

Browning, Robert. Justinian and Theodora, rev. ed. London: Thames and Hudson, 1987.

Diehl, Charles. Theodora: Empress of Byzantium, trans. Samuel R. Rosenbaum. New York: Ungar, 1972. (Originally published 1904.)

Procopius of Caesarea. History of the Wars and Secret History. Loeb Classical Library Series. London and Cambridge, Mass.: Heinemann/Harvard University Press, 1914-1935. (With reprints; translations.)

The Ostrogoth king Theodoric (Theodoric the Great; Thiudareiks, "leader of the people"; c. 454—526) was the son of Thiudmir. As a boy of seven or eight, he was sent as a royal hostage to Constantinople to be reared along with other aristocratic children. That Theodoric remained unable to write never constrained his love of literature and theological discussion. He returned to his people as a man in 471 and with the aid of his father immediately began to assemble a following and lead them in battle. Thereby designated to succeed his father as king of the Ostrogoths, he did so in 474; but he then had to contend with Theodoric Strabo, leader of a rival line and magister militum praesentalis, for the rest of the decade. Their struggle was a competition for imperial support, political and economic, which was pivotal in securing the loyalty of the Ostrogoths then resident in the Balkans, Despite his eventual triumph and his own rise to the magistership (483-487) and the consulship in 484, Theodoric the Great's relationship with the government in Constantinople remained strained. In 489, he was invited to lead his people into Italy as allies of the Romans and depose Odovacar, who was patricius and "king." After four years of war and attempted compromise, Theodoric hewed his adversary in two with his own hand. Theodoric then ruled from Ravenna until his own death.

Theodoric the man was complex, sometimes extremely volatile, but usually careful and calculating in the pursuit of his personal vision of the new realities within the Roman empire. His exact position remained ambiguous: rex, Flavius, patricius, pius princeps invictus semper, but never Augustus. He expanded the Amalian network of family alliances to include most of the ruling families of contemporary Germanic kingdoms, suggesting—as his correspondence also suggests—that he saw himself, his family, and the Ostrogothic kingdom as leading the western empire. He was also regent for the child king of the Visigoths, Alaric II. The Visigoths soon regarded the Ostrogothic forces dispatched by Theodoric as foreign and obtrusive. Theodoric's careful use of titles and attempts to have these confirmed or clarified by the emperor in Constantinople reveal that he thought of his and the other Germanic kingdoms as peculiar regional variations under Germanic kings serving simultaneously as imperial officials within the imperium Romanum, not as replacements for it.

Within the Ostrogotiiic domain, Theodoric envisioned that the Gothic and Roman populations should complement one another with clearly recognized spheres of expertise allocated to their ruling elites—specifically, leadership in the military for the Goths while the administration of the civil bureaucracy remained in Roman hands. The two branches of one society would come together only in his hands or those of his family. In other words, Theodoric tried to stand at the apex of the countervailing currents of an age that saw itself as very much a part of the universal Roman empire. Beneath the royal family, he tried to control the peaceful fusion of peoples and cultures. In fact, however, his reign provided many unregulated opportunities for Ostrogoths and Romans to share ideas and blood without regard to royal wishes. Theodoric's vision was not lost on his successors, who continued to reach back to him for guidance and legitimacy. The Niebelungenlied enshrined Theodoric as Dietrich von Bern, and the writings of Cassiodorus and Jordanes left the Latin world ample testaments of Theodoric's subtle governmental policies.

Tomb of Theodoric, Ravenna. Photograph courtesy of John W. Barker.

Although Theodoric was an Arian Christian, he tolerated Orthodoxy and Judaism, saying that no king could tell his people what to believe. Such an enlightened attitude, combined with the peculiar relationship he maintained with Roman institutions, at once inside but independent, supported a religious and cultural flowering during his rule among the Roman populations. Pope Gelasius I and others took advantage of the independence of Italy within the imperial system to fashion a similar theoretical autonomy for the papacy and the Christian church in the west. Boethius and a circle of aristocratic scholars in support of Theodoric saved much of ancient Greek philosophy from extinction by their devotion and their Latin translations. Cassiodorus (fl. c. 507-580) wrote extensively, thereby serving history and Christianity as loyally as he served Theodoric and Theodoric's successors. It is difficult to separate the vision of Cassiodorus and his student Jordanes from that of Theodoric. However, in areas where Theodoric's independence of thought cannot be doubted—such as in coinage, architecture, foreign policy, and titles—Theodoric himself clearly stands out as the seminal craftsman of his age. Cassiodorus was in sympathy with him and, in a sense, became his mouthpiece. In his own statements and actions, Theodoric was acutely conscious of displaying the imperial virtues of leadership—justice, clemency, piety, and manliness. He was also a proven warrior and general. His support of a gifted intellectual circle and numerous building programs in Ravenna, Verona, Rome, and elsewhere ensured that his virtues would receive lasting recognition. For him and a few other Germanic contemporaries, these attributes denoted their own successful leadership of Roman-Germanic society, naturally in the line of Augustus, but divorced from the office of emperor and therefore accepted within the emerging pattern of western rule. Ornaments for personal dress inspired by Ostrogothic tastes and manufactured in Ravenna flowed northward far beyond the Alps.

Theodoric's jurisdiction included all of Italy, Sicily, Provence in France, Bavaria, southern Austria, and northern Yugoslavia, with a regency over Visigothic lands in southwestern France and Spain. In most of the outlying areas Theodoric ruled through a few agents or garrisons. Yet in many areas Theodoric was the last effective representative of Rome. His final years were filled with disappointment. He suspected many members of his Roman-Orthodox aristocratic circle of treason against him and ordered Boethius executed; most of his marriage alliances with fellow Germanic kings ended in failure; his grandson and successor Athalaric was a minor.

Theodoric died of dysentery in 526 and was buried in Ravenna. His mausoleum is much like the man—a strange and complex mingling of Germanic traditions within Roman forms.

See also Boethius; Cassiodorus; Gelasius, Pope; Jordanes, Chronicler; Odovacar; Ostrogoths; Ravenna; Visigoths

THOMAS S. BURNS

Collaci, Antonio. Teodorico il grande. Milan: Mursia, 2001.

Moorhead, John. Theoderic in Italy. Oxford: Clarendon, 1992.

Theophano (Theophanu, c. 955-c. 991) was a Byzantine (eastern Roman) princess who married Otto II of the Saxon dynasty. The father of Otto II—Otto I—had been rebuffed at least once in an attempt to arrange a marriage between his son and a Byzantine princess. But when the Byzantine emperor Nicephorus II Phocas was overthrown by the more pro-western John I Tzimisces (Zimisces) in December 969, a union was successfully arranged. Theophano arrived in Italy in 972 and married Otto II in April. They had three daughters—Adelaide (b. 977), Sophia (b. 978), and Matilda (b. 979)—and a son, Otto III (b. 980). When her husband died while her son was an infant, Theophano assumed the regency. On Theophano's death, Adelaide, who was Otto II's mother and Otto Ill's grandmother, came out of retirement and took over the regency.

The question of Theophano's influence on Otto Ill's attitudes and policies has been overshadowed by a controversy about precisely who she was. There can be no doubt that she was a Byzantine aristocrat, though she is mentioned in no extant Greek sources. Two theories have been offered about her exact identity: first, that she was a sister of the future emperor Basil II; and second, that she was a kinswoman of John I Tzimisces. Recent scholarship indicates that Theophano was most likely John's niece by marriage, the daughter of his brother-in-law, the patrician Constantine Sclerus, and Constantine's wife, Sophia.

See also Otto II; Otto III

MARTIN ARBAGI

Regino of Priim. Chronicon, ed. F. Kurze. Scriptorum Rerum Germanicarum in Usum Scholaruiri ex Monumentis Germaniae Historicis Separatim Editi. Hannover and Leipzig: Hahnische Buchhandlung, 1890.

Thietmar (Ditmar). Chronicon, ed. F. Kurze. Scriptorum Rerum Germanicarum in Usum Scholarum ex Monumentis Germaniae Historicis Separatim Editi. Hannover and Leipzig: Hahnische Buchhandlung, 1889.

Dolger, Franz. Wer war Theophano?" Historische Jahrbuch, 62, 1949, pp. 646-658.

The Empress Theophano: Byzantium and the West at the Turn of the First Millennium, ed. Adelbert Davids. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Jenkins, Romilly. Byzantium: The Imperial Centuries, A.D. 610—1071. New York: Random House, 1967.

Kreutz, Barbara. Before the Normans: Southern Italy in the Ninth and Tenth Centuries. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1991.

Leyser, Karl. "The Women of the Saxon Aristocracy." In Rule and Conflict in an Early Medieval Society: Ottoman Saxony. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1979, pp. 49-73.

Wolf, G. "Nochmals zur Frage: wer war Theophano?" Byzantinische Zeitschrift, 81(2), 1988, pp. 272-283.

Saint Thomas Aquinas (Tommaso d'Aquino, c. 1225—1274) is perhaps the most broadly influential philosopher and theologian in the entire Catholic tradition—his only serious rival for the title would be Augustine. Thomas was born at Roccasecca, near Aquino (whence his customary toponyrnic), to an aristocratic family. He was presented at an early age as an oblate to the Benedictine monastery at Monte Cassino. He studied there and in Naples (after 1239) before disappointing his family's hopes for his ecclesiastical preferment by developing an interest in the then recently founded Order of Preachers (Dominicans), which he entered in 1244. Despite initially intense opposition from his family (who went as far as imprisoning him for nearly two years in an attempt to break his resolve), he spent the rest of his life serving the Dominicans as a teacher, scholar, preacher, and writer. His studies took him far afield: first to Paris, where he had a decisive intellectual encounter with the theologian Albert the Great; then, following Albert, to Cologne in 1248-1252; then again to Paris, where he remained until 1259, pursuing the normal career path of an academic theologian by giving courses of lectures on the Bible and the Sentences of Peter Lombard, and taking his master's degree in theology in 1256. Returning to Italy in 1259, he taught in various places (Anagni, Orvieto, Rome, Viterbo) until being appointed to a chair of theology at Paris in 1268. His brief tenure there was marked by fierce controversy with other Parisian masters, including Siger of Brabant, whose well-known rivalry with Thomas is reflected in their presence—suitably reconciled—in the same sphere of Dante's Paradiso.

In 1272, perhaps (and, if so, understandably) weary of academic infighting, Aquinas returned to Italy and settled down to a life of study at a Dominican priory in Naples. This life was interrupted by a summons to attend the Council of Lyon in early 1274. While staying en route at the Cistercian abbey of Fossanuova, he died suddenly—poisoned, according to an unconfirmed but persistent contemporary legend, on the instructions of Charles of Anjou. Whatever its cause, his death did not appease his Parisian rivals, who worked energetically (and with some success) for the condemnation of his teachings in the 1270s; but in 1278 the Dominican order granted his writings official protection (at least within the order itself), and thereafter his reputation grew steadily. He was canonized by Pope John XXII in 1323. By the mid-sixteenth century, his importance to Catholic thinkers had reached a point where he could be seen by many as the presiding genius of the Council of Trent and, indeed, of the whole phenomenon of the Counter-Reformation: Pope Pius V proclaimed him a doctor of the church (doctor angelicus) in 1567. A modern rediscovery of Thomas's thoughts and writings among both lay and clerical thinkers, beginning in the 1870s with Leo XJII's laudatory bull Aeterni patris (1879), inspired the major current in twentieth-century Catholic thought known as neo-Thomism; and non-Catholic philosophers have shown increasing interest in him since the Second Vatican Council (1262-1265) inaugurated an era in which it became easier to consider the intellectual substance of his work independent of its confessional affiliation.

That substance is not easy to sum up in a few words, especially given Thomas's dauntingly vast output of writings. Speaking generally, however, it may be said first of all that Thomas, as both philosopher and theologian, sets a high value on the existence and workings of human reason (rather than disparaging it, as a mystic might). Therefore, he grants philosophy a specific and indeed crucial role in his overall scheme, as an intellectual activity which is both distinct from and inferior to theology but which is also an indispensable prolegomenon to theological study and is itself capable of exploring and expounding truths about the world and humanity's place in it. The relationship between reason and faith; the attempt to define their respective spheres of operation; and the consequences of such a definition for the individual human being's understanding of self, the world, and God thus stand at the very center of Thomas's preoccupations throughout his works. These works proceed from his sarly commentaries and manuals of quaestiones disputatae (derived from his teaching); through the Summa contra gentiles, begun c. 1258 as a handbook of natural theology for use by missionaries against the nonbelievers"; and many more treatises, commentaries, and expositions of biblical and Aristotelian texts; to his masterpiece, the Summa theologiae, begun in the mid-1260s and left unfinished at his death. The Summa theologiae has been recognized down to the present day as a uniquely authoritative achievement in the systematic exposition and analysis of Christian doctrine.

A11 these writings are based on Aquinas's absolute faith in revelation, but with the conviction that revelation is susceptible, up to a point determined only by the limitations imposed by our essential humanness, of being understood. He therefore stands in the Anselmian tradition of fides quaerens intellectum, but, far more than his eleventh-century predecessor Anselm, he sets out to deepen his fellow Christians' understanding of their own faith by using intellectual and analytical tools bequeathed to him by pagan traditions of thought: Neoplatonism and, above all, Aristotelianism. His many commentaries on Aristotelian texts thus stand beside his biblical commentaries not in opposition (as a strong current of antipaganism in Christian thinking, harking back at least to Jerome, would have wanted), and not as hostile demolitions of intellectual straw figures, but as respectful recognitions of incomplete gestures in the direction of truth that he is seeking to integrate into his own attempt at intellectual synthesis. The rediscovery (and translation into Latin) of Aristotle's works, which had been ongoing in the west since the twelfth century, enabled Aquinas to revivify both philosophy and theology, The greater subtlety and precision of argument made possible by the adoption of concepts and terminology from the Aristotelian corpus were as useful in debates about the workings of human reason as they were in debates about the proper understanding of divine revelation—debates which, for Thomas himself, were in the last analysis no more than mutually interdependent efforts to advance from different starting points toward the same resplendent truth.

See also Albertus Magnus; Aristotle and Aristotelianism; Averroes and Averroism; Dante Alighieri; Dominican Order; Peter Lombard; Siger of Brabant

STEVEN N. BOTTERILL

Thomas Aquinas. Opera omnia. Rome: Typographia Polyglotta S. C. de Propaganda Fide, 1882. (Editio Leonina.)

—. Summa theologiae. London: Blackfriars; New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964-1981. (Latin text and English translation.)

—. Opera omnia, ed. Roberto Busa, 2nd ed. Milan: Editoria Elettronica Editel, 1996. (CD-ROM.)

The Cambridge Companion to Aquinas, ed. Norman Kretzmann and Eleonore Stump, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Davies, Brian. The Thought of Thomas Aquinas. Oxford: Clarendon, 1992.

Gilson, Étienne. The Christian Philosophy of Saint Thomas Aquinas, trans. L. K. Shook. Notre Dame, Ind.: University of Notre Dame Press, 1994.

Weisheipl, James A. Friar Thomas D'Aquino: His Life, Thought, and Work. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1974.

Thomas of Celano (c. 1190-1260) was a Franciscan hagiographer, the author of the first two lives of Francis of Assisi. Little is known about Thomas's early life, except that he was apparently from a noble family and received a good education. He joined the Franciscan order in the first years of its existence, probably in 1215, and volunteered for the first Franciscan mission to Germany in 1221. He seems to have shown administrative talent, for the next year he was made custos of a substantial part of the central European province, and in 1223 he was appointed vicar for the entire province while its minister was in Italy. In 1224, Thomas returned to Italy. He may have been present when Francis died in 1226.

Thomas's reputation as a preacher and stylist and his status as a relatively early follower of Francis seem to be the reasons Pope Gregory IX commissioned him in July 1228 ro write an official life of the saint. While preparing the work, Thomas amassed a huge collection of anecdotes from friars and laymen that became a source for several later lives of Francis. By February 1229, he had finished what would come to be called Vita prima. Written in cursus, or rhythmical prose, the Vita prima is a skillful attempt to convey the interior life of Francis as early Franciscans knew it. But in many ways it is also a conventional stereotyped hagiography. It emphasizes Francis's spiritual journey and ideals but omits some of the quirkiest and most compelling episodes of the saint's life. In 1230, Thomas edited the Vita prima into a liturgical epitome, the Legenda ad usum chori.

Alt hough the Vita prima was greeted with enormous enthusiasm when it first appeared, by the early 1240s many friars were voicing dissatisfaction with it, apparently because so many favorite stories about Francis had been left out. In 1244, the Franciscan general chapter invited all friars who had known Francis to submit their reminiscences so that a new, more complete vita could be composed. Thomas was once again called on to be the author. From materials he had not used in his first life and from recently submitted anecdotes, Thomas crafted the Memoriale in desiderio animae de gestis et verbis sanctissimipatris nostri Francisci, usually called the Vita secunda. Like the first life, it tells the story of Francis's conversion; but in its second part the anecdotes are arranged as a kind of prolonged character study of the subject. The Vita secunda—unlike the Vita prima—confronts matters of controversy within the order, especially a growing dispute over the relaxation of the rule. Thomas clearly depicts Francis as favoring a strict adherence to the rule and lamenting the corruption of his order by those who sought to relax it.

If "laxists" found the general message of the Vita secunaa distasteful, many throughout the order complained that it gave insufficient attention to Francis's miracles, a subject that had been carefully elaborated in the Vita prima. To remedy this, Thomas composed a Tractatus de miraculis in 1255-1256 that detailed almost 200 of Francis's miracles. Thomas may also be the author of the Legenda sanctae Clarae, a life of Francis's friend Saint Clare written in the mid-1250s.

Thomas died in 1260 at Tagliacozzo. His works survived, despite a directive of the Franciscan chapter general of 1266 ordering that they and all other lives of Francis be destroyed to facilitate acceptance of Bonaventure's Legenda maior as the only official version of Francis's life.

See also Bonaventure, Saint; Francis of Assisi; Franciscan Order

THOMAS TURLEY

Thomas of Celano. Saint Francis of Assisi: First and Second Life of Saint Francis, with Selections from the Treatise on the Miracles of the Blessed Francis, trans. Placid Hermann. Chicago, EL: Franciscan Herald, 1963.

Bontempi, Pietro. Tommaso da Celano, storico e innografo. Rome: Scuola Salesiana del Libro, 1952.

De Beer, Francis. La conversion de Saint Francois selon Thomas de Celano. Paris: Éditions Franciscaines, 1963.

Facchinetti, Vittorino. Tommaso da Celano: 11 primo biografo di San Francesco. Quaracchi: Collegio di San Bonaventura, 1918.

Miccoli, Giovanni, "La 'conversione' di San Francesco secondo Tommaso da Celano." Studi Medievali, Series 3(5), 1964, pp. 775-792.

Moorman, John R. H. Sources for the Life of Francis of Assisi. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1940, (Reprint, Farnborough: Gregg, 1966.)

Spirito, Silvana. Il francescanesimo di fra Tommaso da Celano. Assisi: Edizioni Porziuncola, 1963.

The Tiepolo family, a merchant house, is first recorded at Malamocco in the Venetian lagoon but evidently immigrated to Venice in the later eleventh century. Members of the family were trading in Constantinople in the 1080s and thereafter maintained strong interests in the Orient. They entered public life in the twelfth century and reached their greatest prominence—twice occupying the office of doge—in four consecutive generations between the early thirteenth century and the early fourteenth.

Of the two Tiepolo doges, the first (Venice's forty-third) was Giacomo (lacopo, Jacopo), who had achieved distinction in the east. His election in 1229 broke the hold on the chief magistracy of the ancient patrician houses, particularly those of Ziani and Dandolo, who resented the upstart's rise, while a lasting rivalry between nobiles and populares was emerging. Giacomo showed extraordinary skill in his dealings with the hostile emperor Frederick II, Ezzelino III da Romano, and other powers, though he was to be chiefly remembered for commissioning a new legal code (1242). Under him, the comune approached the ideal of maximum authority with maximum consensus, and his firm rule was credited with the peace and prosperity of the years immediately following his death (1249).

Giacomo's son Lorenzo became the forty-sixth doge (1268-1275), having married a niece of John of Brienne, Latin emperor of Constantinople, and having made his name by leading the reconquest of Acre (1258) with a crushing naval victory over the Genoese. Lorenzo was a very popular choice, and on his election he formally reconciled his house with that of Dandolo. He subsequently placated the guilds by allowing them limited self-government.

On the death of Doge Giovanni Dandolo (1289), a favored possible successor was a second Giacomo Tiepolo, who was the son of Lorenzo and was another victorious admiral. However, in electoral circles this Giacomo was seen as representing a threat of a hereditary signoria such as was taking shape elsewhere—something the evolving Venetian constitution resolutely opposed. In the event, Giacomo served Venice by avoiding election and the social strife that would have ensued.

Baiamonte, son of the younger Giacomo, did not share his father's deference to public interests. In 1310, he led an armed rising against the regime headed by Doge Pietro Gradenigo, whom he sought to replace. The insurrection failed, however, and Baiamonte was exiled by a ten-man commission established to deal with the emergency, a body that subsequently became known as the consiglio dei died and developed into a permanent and prominent institution of the Venetian state. The Baiamonte episode prompted the oligarchy to take still stricter measures to stifle any personality cult.

Partly, it may be inferred, as a result of Baiamonte's failure, the family was never so conspicuous again. It is reckoned to have been in Venice's top ten families in the 1260s, but a social chronicle of the 1350s places it in the second twelve, and a modern assessment has it just outside the top forty around that time. Later, the house produced its most illustrious scion of all, the Rococo painter Giovanni Battista (1696-1770). It is still today a respected component of Venetian society.

See also Venice

JOHN C. BARNES

Cracco, G. Società e stato net medioevo veneziano (secoli XII-XIV). Florence: Olschki, 1967.

Lane, Frederick C. Venice: A Maritime Republic. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973.

Zorzi, A. La repubblica del leone: Storia di Veneziw. Milan: Rusconi, 1979.

Tino di Camaino (c. 1280 or 1285-1337) was a Sienese sculptor. Although his works are numerous and varied, representing the range of activities of a late medieval workshop, Tino is best-known for a series of important sepulchral monuments carved and erected in Siena, Pisa, Florence, and Naples.