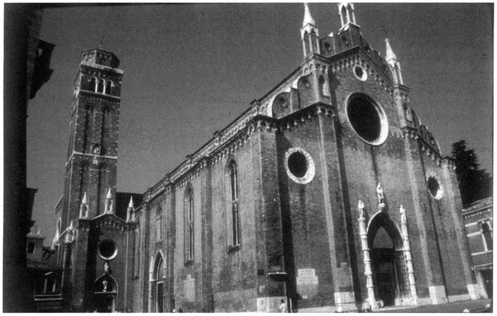

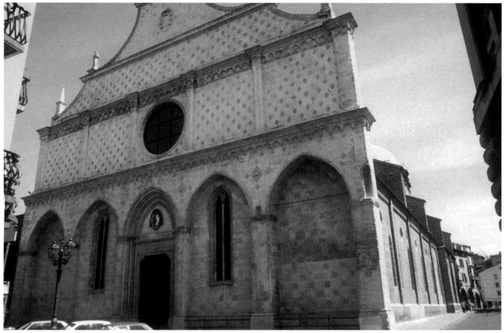

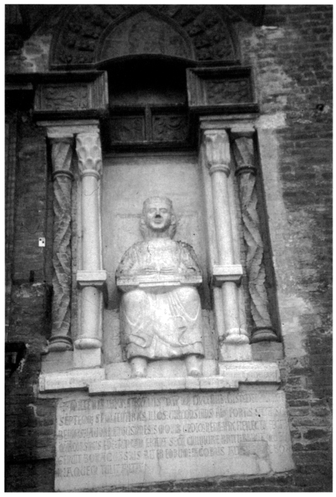

Church of Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, Venice. Photograph courtesy of John W. Barker.

Emperor Valentinian III (Placidus Valentinianus, Flavius Valentinianus; 419-455, r. 425-455) was the son of the emperor Honorius's sister Galla Placidia and the patrician (later emperor) Constantius, and the brother of J usta Grata Honoria. In the early 420s, Valentinian was proclaimed nobilissimus ("most noble") by his uncle Honorius, but neither this title nor his father's emperorship was initially recognized in the east. After his mother had a falling-out with Honorius, the young Valentinian accompanied her and his sister to exile at the court of his cousin Theodosius II (401 or 402—450) at Constantinople. The attitude of the eastern court toward Valentinian changed in 423, when the usurper Johannes seized power in the west. Valentinian was first reaffirmed as nobilissimus in 423-424 and then named Caesar (junior emperor) in 424. Also in 424, he was betrothed to his cousin Licinia Eudoxia, the daughter of Theodosius II. In 425 Valentinian was proclaimed Augustus at Rome after the defeat of Johannes, and in 437 he returned to Constantinople for his marriage. Merobaudes wrote a poem (now partially extant) in honor of the wedding.

In the early years of his reign, Valentinian was overshadowed by his mother. After his marriage, much of the real authority lay in the hands of the patrician and master of soldiers Aetius. Nor does Valentinian seem to have had much aptitude for ruling. He is described as spoiled, pleasure-loving, and influenced by sorcerers and astrologers. He divided his time primarily between Rome and Ravenna. Like his mother, Valentinian was devoted to religion. He contributed to two churches of Saint Laurence, in Rome and Ravenna. He also oversaw the accumulation of ecclesiastical authority in the hands of the bishop of Rome as he granted ever greater authority and prestige to Pope Leo I (the Great, r. 440-461) in particular.

Valendnian's reign saw the continued dissolution of the western empire. By 439, nearly all of North Africa was effectively lost to the Vandals, although Valentinian did attempt to neutralize that threat by betrothing his sister Placidia to the Vandal prince Huneric. In Spain, the Suevi controlled the northwest, and much of Gaul was to all intents and purposes controlled by groups of Visigoths, Burgundians, Franks, and Alans. In 454, Valentinian murdered his supreme general, Aetius, presumably in an attempt to rule in his own right. But the next year he himself was murdered by two members of his bodyguard who had been partisans of Aetius.

Although Valentinian was ineffectual as a ruler, his legitimate status and his connection to the old ruling dynasty provided a last vestige of unity for the increasingly fragmented Roman empire. After his death, the decay of the west accelerated. The different regions of the west went their own way, and the last several western emperors, the so-called shadow or puppet emperors, were usually overshadowed by one barbarian general or another and were also limited primarily to Italy.

See also Aëtius, Flavius; Eudoxia; Honorius, Emperor; Galla Placidia

RALPH W. MATHISEN

Codex Theodosianus, ed. P. Kruegeri and T. Mommsen. Hildesheim: Weidmann, 1990. (Originally published 1905.)

Haenel, Gustav Friedrich. Novellae Valentiniani III. Leipzig: Teubner, 1850.

The Theodosian Code and Novels, and the Sirmondian Constitutions, trans. Clyde Pharr. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1952.

Barnes, Timothy D. "Patricii under Valentinian III." Phoenix, 29, 1975, pp. 155-170.

Ensslin, Wilhelm. "Valentinians III. Novellen XVII und VIII von 445." Zeitschrift der Savigny-Stifiungfür Rechtsgeschichte: Romanistische Abteilung, 57, 1937, pp. 367—378.

Musumeci, Anna Maria. "La politica ecclesiasdca di Valentiniano III." Siculorum Gymnasium, 30, 1977, pp. 431-481.

Selb, Walter. "Episcopalis audientia von der Zeit Konstantins bis zur Nov. XXXV Valentinians III." Zeitschrift der Savigny-Stiftungfür Rechtsgeschichte: Romanistische Abteilung, 84, 1967, pp. 162-217.

The Roman writer Valerius Maximus (fl. c. a.d. 20) was of undistinguished origins. He accompanied the proconsul Sextus Pompeius to Asia c. 27. After returning, Valerius wrote (c. 29— 32) a collection of historical anecdotes, Factorum et dictorum memorabiiium libri (Books of Memorable Words and Deeds), which was dedicated to the emperor Tiberius (r. 14-37). This book includes extracts from Cicero, Sallust, Livy, Pompeius Tragus, and others; the extracts are divided into two categories— "domestic" and "foreign"—and are usually concerned with various moral traits. The book is full of rhetorical artifice and is in general a characteristic production of the Latin "silver age." Two epitomes were made in the fourth and fifth centuries, and the work was a popular school text during the Middle Ages.

RALPH W. MATHISEN

Duff, J. Wight, and A. M. Duff". A Literary History of Rome in the Silver Age: From Tiberius to Hadrian, 3rd ed. London and New York: Barnes and Noble, 1964, pp. 54-66.

Kempf, Carolus, ed. Valerii Maximi Factorum et dictorum memorabilium libri novem cum Iulii Paridis et Ianuarii Nepotiani epitomis. Leipzig: Teubner, 1888.

See Camaldoli; Giovanni Gualberto, Saint

The Vandals are believed to have originated in Scandinavia in the distant past. By the second century after Christ, they occupied the area around Silesia and were divided into the Silings and the Asdings. During the third and fourth centuries, they frequently raided the Roman empire, and some Vandals accompanied Radagaisus in his invasion of Italy in 405. On 31 December 406, a horde of Asding and Siling Vandals, accompanied by Alans, Burgundians, and Suevi, crossed the frozen and unprotected Rhine into Gaul. In 409, all but the Burgundians passed into Spain. In 416, the Silings and Alans were overwhelmingly defeated by the Visigoths. Their remnants then joined the As-dings, whose kings henceforth were known as kings of the Vandals and Alans.

In 428, Gaiseric, who was to become one of the most able Germanic kings of the period, succeeded to the Vandal throne. In the next year, he led an estimated 80,000 Vandals and Alans across to Africa, perhaps having been invited to do so by a disaffected Roman count. In 439, Carthage itself was captured. The loss of North Africa was a disaster for the western empire. Not only did it put much of the grain supply of Italy into enemy hands; it also gave the Vandals an opportunity to take to piracy. Vandal raiders descended on the coasts of Italy, Spain, and even Greece. In 455, Gaiseric went so far as to land at Ostia, the port of Rome. Pope Leo I was said to have met him and prevented an out-and-out sack, but the Vandals nevertheless looted and plundered for fourteen days. They returned to Carthage not only with the spoils taken by Titus from Jerusalem in A.D. 70 but also with the empress Eudoxia and her daughters Eudocia and Placidia. Placidia was then married to Gaiseric's son Hun-eric.

Unlike the Germanic settlers in Europe, the Arian Vandals had difficulty reaching an accommodation with the local Roman population. They persecuted the Catholics, and many bishops went into exile, often to either Sardinia or Italy. Other Romans also fled to Italy and the east. The Vandal kingdom came to an end in 533, when the emperor Justinian's general Belisarius defeated the last Vandal king, Gelimer, in two battles. Of all the Germans who occupied the Roman empire, the Vandals probably had the least lasting impact.

See also Belisarius; Eudocia; Eudoxia; Gaiseric the Vandal

RALPH W. MATHISEN

Cessi, Roberto. "La crisi imperiale degli anni 454-455 e l'incursione vandalica a Roma." Archivio della R. Società Romano, di Storia Patria, 40, 1917, pp. 161-204.

Courtois, Christian. Les Vandales et l'Afrique. Paris: Arts et Métiers Graphiques, 1955.

Gautier, E. F. Genseric: Rot des Vandales. Paris: Payot, 1932, pp. 240-247.

Although a number of Sienese paintings are attributed to Andrea di Vanni d'Andrea (fl. c. 1332-1414), he is not a well-known painter. He was active in Siena, and his work is found in frescoes and panel paintings; but his birth and death dates remain unknown, and even his relationship to his contemporary Lippo Vanni has not been clearly established. Andrea is identified as sharing a workshop with Bartolo di Fredi for two years (1353-1355). Berenson (1968) identifies only one of Andrea Vanni's works as signed, a triptych of the Agony in the Garden, Crucifixion, and Descent into Limbo (Washington, Corcoran Gallery, c. 1383). In 1370, he was working on mages of the Blessed Andrea Gallerani with Antonio Veneziano in the duomo of Siena. Andrea Vanni is last documented on two trips to Naples in 1375 and 1383, but other works are attributed to him well after these dates.

Andrea Vanni's work shows the strong influence of many well-known Sienese painters of the first half of the century: Lippo Memmi, Simone Martini, and the Lorenzetti brothers. His conservative stylistic approach, however, appears to have been governed by choice rather than by social or historical circumstances; evidently, then, his style was accepted and found a market during the period after the plague. Frescoes formerly attributed to him or to Simone Martini are now attributed to Bartolo di Fredi, indicating a parallelism of styles among the Sienese workshops.

Andrea Vanni's work centers in Siena, where he is known to have been active from the 1350s through the first decade of the fifteenth century. Among his most important Sienese works are the following: frescoes painted in the Sala dei Cardinali (Palazzo Pubblico), which bear the partial date "136—"; a Madonna Lactam in the church of San Donato; a fresco of Saint Catherine of Siena in the Cappelle delle Volte in San Domenico; and three panels from a polyptych of Saint Anne holding Mary, Saint Ursula, and Saint Agnes. Works of his have also been identified in the environs of Naples at Aversa, in the Cappella di Casaluce, dating from his trip to this region in 1375. These frescoes include scenes of the Dormition and Assumption of the Virgin, accompanied by representations of saints Anthony Abbot and Catherine of Siena. A work dating from 1398 was painted in collaboration with Giovanni di Paolo in the first chapel to the right of the choir of San Francesco. It was followed by a polyptych for the high altar of Santo Stefano in the tradition of Duccio's Maestà. This large altarpiece portrays an Enthroned Madonna and Child with Fourteen Saints and the Four Evangelists. Andrea Vanni's early relationship to Bartolo di Fredi becomes apparent when one compares his Adoration of the Magi (New Orleans, Isaac Delgado Museum, Kress Collection) with panels of the Adoration by Bartolo. Both of them seem to have influenced the Strozzi Adoration (Florence, Ufifizi) by Gentile da Fabriano (c. 1370— 1450), in their Lorenzettian conflations of the iconography with the misbehaving animals in the background and orientalizing motifs. Even the saddle on which Mary is sitting represents as much a departure from conventional Sienese images of this subject as the altar on which Gentile places his Madonna and Child. Another work attributed to Andrea Vanni is a Madonna in the Palazzo Comunale in Seggiano.

Andrea Vanni's oeuvre is closely linked to that of his predecessors Simone Martini, Lippo Memmi, and the Lorenzetti, and to that of his contemporaries Luca di Tommè and Giacomo di Mino; it is thus at the hub of fourteenth-century Sienese painting.

See also Bartolo di Fredi Cini; Lorenzetti, Pietro and Ambrogio; Martini, Simone; Memmi, Lippo

DARRELL D. DAVISSON

Berenson, Bernard. Pictures of the Italian Renaissance, Central ana North Italian Schools, Vol. 1. London and New York: Phaidon, 1968, pp. 440-442.

Christiansen, Keith. Early Renaissance Narrative Painting in Italy. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1983.

De Benedictis, Cristina. La pittura Senese 1330-1370. Florence: Salimbeni Libreria Editrice, 1979.

Edgell, George Harrold. A History ofSienese Painting. New York: L. MacVeagh, Dial, 1932.

Fehm, Sherwood. "Attributional Problems Surrounding Luca di Tommè." In Essays Presented to Myron P. Gilmore, ed. Sergio Bertelli, Gloria Ramakus, and Craig Hugh Smyth, Florence: La Nuova Italia, 1978.

Meiss, Millard. French Painting in the Time of Jean Due de Berry. London: Phaidon, 1967.

Van Marie, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. The Hague: Nijhoff, 1923-1938. (Reprint, New York: Hacker, 1970.)

Lippo Vanni was born in Siena and raised in the Sienese artistic traditions of the early Trecento. He emerged as one of the city's masters of illusionism. His earliest work appears to be largely in miniatures, but he went on to wall frescoes and panel paintings. He is first documented in 1344, when he was commissioned by the spedale (hospital) of Santa Maria della Scala to paint an illuminated book. He was then accused of having taken and pawned a chorale book owned by the hospital, and a court order and soldiers were necessary to retrieve the book—an episode suggesting that Vanni either was a thief or was embroiled in a dispute over his wages.

Lippo Vanni's style reflects strong influences from Lippo Memmi, the Lorenzetti brothers, Simone Martini, and the miniaturist Niccolò di ser Sozzo Tegiiacci. For example, the painted cover of a gabella (city tax book) of 1345, formerly attributed to Ambrogio Lorenzetti, is probably the work of Vanni; their styles are very close. Among Vanni's earliest works are miniatures in the corale of Libro dei Conti Correnti (1345; Siena, Opera del Duomo, Corale n. 4), the Gradual for the Collegiata at Casole d'Elsa (c. 1345-1350), the Berry Antiphonary (Fogg Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts), and a roundel held by angels over the entrance door to the monastery church of Lecceto. Works attributed to Vanni from the period 1350-1360 include a Madonna and Child (Perugia, Galleria Nazionale dell'l/'mbria); a seminary chorale book (Siena, Seminario Pontificio Pio XII); an antiphonary (Siena: Opera del Duomo); and a fresco of the Madonna and Saints for the seminary in Siena, which presents itself as though it were a regular polyptych with gilded wooden frame and other details. For the monastery church of Santi Domenico and Sisto in Rome, Vanni painted the triptych of Saint Aurea, showing the Madonna and child enthroned with saints Aurea and Dominic and angels; Eve is seated at the feet of the Madonna, and the tempter serpent is writhing on the floor. This unique work is signed and dated (1358). Between 1360 and 1370, Vanni decorated the triumphal arch over the choir and painted a series of frescoes depicting the life of the Virgin at the church of San Leonardo al Lago, in the province of Siena. Lippo also painted a reliquary triptych of saints Dominic, Peter Martyr, and Thomas Aquinas (1372-1374; Vatican Galleries, Museo Cristiano). Another reliquary triptych (in the Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore) dates from c. 1374-1375. Vanni painted in grisaille the Battle of Torrita in the Val di Chiana in the Sala del Mappamundo of the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena (1363) and worked on the vaults of the duomo with Antonio Veneziano (1369-1370). In 1372, Lippo executed a fresco of the Annunciation in the church of San Domenico in Siena.

See also Lorenzetti, Pietro and Ambrogio; Martini, Simone

DARRELL D. DAVISSON

Berenson, Bernard. "Due nuovi dipinti di Lippo Vanni. Rassegna d'Arte, 1, 1914, pp. 97-104.

Carli, Enzo. Lippo Vanni a San Leonardo al Lago. Florence: EDAM, 1969.

Dale, Sharon. "Lippo Vanni: Style and Iconography." Dissertation, Rutgers State University of New Jersey, 1984.

De Benedictis, Cristina, La pittura Senese 1330-1370. Florence: Salimbeni Libreria Editrice, 1979.

E.dgell, George Harrold. A History of Sienese Painting. New York: L. MacVeagh, Dial, 1932.

Meiss, Millard. "Quattro disegni di Lippo Vanni: Nuovi dipinti e vecchi problemi." Rivista d'Arte, 30, 1955, pp. 137-142.

Os, Henk W. van. "Lippo Vanni as a Miniaturist." Simiolus, 7, 1974, pp. 67ff.

Venturi, Adolfo. Storia dell'arte italiana, Vol. 5, La pittura del Trecento e le sue origini. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1907.

Vertova, L. "Lippi Vanni versus Lippo Memmi." Burlington Magazine, 112, 1970, pp. 437-441.

The earliest undisputed date for Paolo Veneziano (died c. 1362) is 1333, when he signed and dated a triptych, the Dorrnition of the Virgin, formerly at San Lorenzo in Vicenza and now in the civic museum there. An art collector in Venice mentions him in a memorandum of 1335. His Madonna and Child Enthroned in the Crespi collection in Milan is signed and dated August 1340. A signed deposition by Paolo of March 1341 is in the Venetian archives, where there was once a document of September 1342 commissioning a throne for use in a state festival from a painter named Paolo. This Paolo, who appears to be the same artist, enjoyed official status at the time. In April 1345, Paolo and his sons Luca and Giovanni signed and dated a panel used to protect the enamel and gold Pala d'Oro on the high altar of the basilica of San Marco. The cover, which is still in place, depicts episodes from the legend of Saint Mark, with half-figure saints and the Man of Sorrows above. A Venetian archival document of January 1346 records payment to Paolo for an altarpiece for the chapel of Saint Nicholas in the ducal palace; two scenes from the life of Nicholas in the Soprintendenza at Florence may have once belonged to it. An Enthroned Madonna and Child at Carpineta in the Romagna bears Paolo's signature and the date 1347. A document of April 1352 in the archives at Dubrovnik relates to an altarpiece by him which is now lost. In 1358, Paolo and his son Giovanni signed and dated the Coronation of the Virgin now in the Frick Collection. Paolo died sometime between then and September 1362, when a Venetian archival document mentions him as deceased.

A large body of undocumented work is attributed to Paolo and his workshop, which is known to have included his sons Luca, Giovanni, and probably Marco, and at least one other artist. This body of work may be divided into two groups. One group falls within Paolo's documented career and is widely accepted, although with differences of opinion concerning chronology and autograph share; the other group is placed before that and is controversial. Important works among the former group are as follows: the votive tomb lunette of Doge Francesco Dandolo in Santa Maria dei Frari in Venice, painted around the time of the doge's death in October 1339; the Enthroned Madonna and Child with angels and donors in the Accademia in Venice, probably c. 1340; the polyptych from Santa Chiara in the same museum, depicting the Coronation of the Virgin and scenes from the lives of Christ, Saint Francis, and Saint Clare, probably from the early 1340s; a dismembered polyptych in San Giacomo Maggiore, Bologna, possibly c. May 1344, when the church was consecrated; a crucifix in the church of Saint Dominic at Dubrovnik, probably the one mentioned in a document of March 1348; dated polyptychs of 1349 at Chioggia, 1354 in the Louvre, and April 1355 formerly at Piran in Istria; and another late polyptych, dismembered, at San Severino in the Marches.

The other group of works, which is a subject of debate, should be attributed to Paolo's early period. It includes the panel masking the sarcophagus of the Blessed Leo Bembo, dated 1321, once in San Sebastiano, Venice, and now at Vodnjan in Istria; the dated Coronation of the Virgin of 1324 in the National Gallery in Washington; five panels from the early life of the Virgin and her parents at Pesaro; an altarpiece with half-length Madonna and child and four scenes from their lives in San Pantalon, Venice; sixteen panels from the legend of Saint Ursula in die Volterra collection in Florence; and a polyptych with an image and narrative of Saint Lucy, originally in her church at Jurandor and today in the bishop's chancellery at Krk in Dalmatia. The undated works were apparently done during the 1320s, in the order listed. The painted donor figures in a wood relief of 1310 at Murano have also been ascribed to Paolo, but they seem too early to have been painted by him and may show the hand of his master. It also has been suggested that Paolo and his workshop illuminated manuscripts and designed or executed mosaics and embroideries.

Although a long Venetian mosaic tradition survived into the fourteenth century, relatively little work on panel or in the other pictorial media was produced in the period immediately before Paolo. The traditional view is that Paolo was the founder and first great master of Venetian Trecento painting, and this view would have to be upheld unless the works assigned to him before his documented activity are rejected. Some of these works, particularly the panels at Pesaro, show the direct influence of Giot to's frescoes in nearby Padua; others, such as the Coronation of the Virgin in Washington, show the intrusion of Gothic style and iconography into the local Byzantine tradition. These same ingredients—the Byzantine, the Gothic, and the Giottesque— are the fundamental elements in Paolo's later works, in which the Gothic becomes more pronounced. The Byzantine and Gothic are so harmoniously blended as to suggest their ultimate common source in the distant classical past; the same might be said of the Giottesque. The influence of the Saint Cecilia Master and the school of Rimini may also be detected. The published literature assumes that, despite the obvious similarities, Paolo attained his style independently of direct Sienese influence. Such examples as his Accademia Madonna, which is close to Duccio's in the Pinacoteca at Siena; and his figures of Saint Catherine in the Sanseverino polyptych and in a panel at Chicago, which resemble Simone Martini's fresco of that saint at Assisi, suggest otherwise. The bold patterns and glowing colors give Paolo's paintings an opulence unequaled even by the Sienese.

Paolo Veneziano had a profound influence on Venetian pictorial art, particularly panel painting, until the end of the fourteenth century. The style that he instituted was continued by Lorenzo Veneziano (whose dated works range from 1357 to 1372) and others into the fifteenth century and the international Gothic style. Paolo had relatively little influence on the mainland, which, with the exception of Istria and Dalmatia, responded to more progressive artistic stimuli.

See also Rimini, School of; Venice: Art

BRADLEY J. DELANEY

Lucco, Mauro, ed. La pittura nel Veneto: II Trecento. Milan: Electa, 1992.

Muraro, Michelangelo. Paolo da Venezia. University Park and London: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1970.

Pallucchini, Rodolfo. La pittura veneziana del Trecento. Venice and Rome: Istituto per la Collaborazione Culturale, 1964.

Il Trecento adriatico: Paolo Veneziano e la pittura tra oriente e occidente, ed. Francesca Flores d'Arcais and Giovanni Gentili. Milan: Silvana, 2002.

The city of Venice is a product of its geography. People settled on the unstable islands where the rivers of northern Italy meet the Adriatic Sea. These islands have been formed, since the last ice age, from rock and silt brought down by rivers and dumped where the tides from the sea meet the freshwater rivers. A row of barrier islands (the lidi) protect the lagoons from the open sea, but the salt water enters into the lagoons daily through the openings in the lido at Chioggia, Malamocco, and San Nicolo di Lido. Two types of river enter the lagoons. Swift-flowing rivers (theTagliamento, Livenza, Piave, Sile, Brenta, and Bacchiglione) rush down from the Dolomite Alps in the north and bring silt and small rocks to deposit before the incoming tides. The rivers coming from the west, which drained the plain of northern Italy (the Adige and the northernmost branch of the Po), move more slowly yet inexorably, bringing finer silt. Against these flows, the saltwater tides enter the lagoons daily from the Adriatic and retreat, scouring the lagoons in channels and cleansing the waters to create a healthy environment in which people can live. On occasion, however, the tides become much higher (acqua alta) and inundate the low-lying islands. On other occasions, the rivers hurry into the lagoons with springtime force, causing flooding. As these flows vary from year to year, channels are created or abandoned by the sea and the islands are raised or, more frequently, subside into the brackish waters. Earthquakes also occasionally threaten the lagoons.

Into this unstable environment came humans. History and archaeology combine to demonstrate that the islands of the northern Adriatic have been inhabited since prehistoric times. The environment of the lagoons stimulated settlement. The brackish waters sheltered fish and birds. Salt could be evaporated from its waters. In addition, the complex of sinuous channels gave protection from invasion by mainlanders and encouraged seafaring. Places that were inhabited in classical times have since become landlocked; for example, the ancient seaports of Ravenna, Spina, Padua, and Aquileia are now far from the Adriatic Sea. In the seventh century, the ancestors of present-day Venetians built their homes farther out in the lagoons, some in places that are uninhabitable today. Up to the ninth century, as we know from only scarce documentation, these early communities grew and then declined as people moved farther out to other islands. In the ninth century, if not before, the complex of islands 2 1/2 miles (4 kilometers) from the mainland, known as the Rial to (the rivo alto, or high bank), became the political and social center of life in the lagoons.

How were buildings constructed on such uncertain land? First, great numbers of poles were driven down into the mud. On top of these were placed platforms of wooden boards and then stone for the foundation of structures. Archaeologists have reported finding wood, stone, and ceramic from layers of mud dated to the sixth and seventh centuries in the lagoons, suggesting the strength of these early settlements. Houses of wood with thatched roofs alternated with gardens, fields, and fisheries, and with watercourses and swamps. By the early thirteenth century, among the great stone structures that had been built were the basilica of San Marco; the churches of San Lorenzo, San Giovanni Decollato, and San Nicolò dei Mendicoli; and the great homes of the Ziani, Bernard us Teutonicus (the German merchant), and Renier Dandolo, son of the doge.

The Venetians recognized the precariousness of their environment. In its earliest official records, the Venetian commune concerned itself with the preservation of the environment. Since the salubrity of the air and the water of the lagoons depended on the daily washing by the saltwater tides, the Venetians attempted to defend the tidal waters and to prevent the narrowing of the lagoons. It was observed that "a large lagoon makes for a great seaport" (gran laguna fa gran porto). Venetians understood that the action of the tides and the deposit of silt from the rivers raised the bottom of the lagoons and created more land. The lagoons also narrowed when people extended the shorelines in order to create more land for agriculture or for buildings. In the fourteenth century, the Venetian republic began to divert the river mouths away from the lagoons so that they emptied into the Adriatic north and south of the lagoons. Furthermore, the republic ordered regular dredging of the channels in the city so that the waters would flow more freely. In the Renaissance, the Venetian republic tried to save the lagoons from silting up by prohibiting the dumping of debris to create more land on the marshes and the mudflats. Thus the Venetians tried to maintain their residence in this inherently unstable environment. The efforts to control this instability increased in the Renaissance and continue to this day.

Today there are 118 islands and more than 200 canals within the heart of the ancient city. The Grand Canal winds in a reverse S-shaped curve over 2 miles (3 kilometers) through the city; the canal is more than 12,000 feet (3,800 meters) long, 100 to 230 feet (30 to 70 meters) wide, and 18 feet (5-5 meters) deep. Forty-five channels (rii) open onto the Grand Canal. Today it is a concern of the world that this unique environment be preserved for its historic heritage.

Romans had visited the lagoons in the pre-Christian era, but the historical record does not confirm settlements until A.D. 537-538, when Cassiodorus mentioned that men from the lagoons supplied Ravenna with salt. After 586, mainland Romans began to flee to the lagoons before the invading Lombards. Roman leaders from Padua settled Chioggia and Malamocco; those from Roman Altino colonized the island of Torcello. People from Opitergo (Oderzo) founded Eraclea (or Cittanova), named for Emperor Heraclius. These centers were separated from each other by marshes, channels, and brackish lakes.

Whereas the mainland became part of the Lombard kingdom, the lagoons honored Constantinople's representative in Italy, the exarch of Ravenna. He appointed dukes chosen from the local tribune class. In the early eighth century, when the Lombards threatened Ravenna, Paolo (or Paulicio) in Eraclea became the first locally chosen duke. He soon transferred his seat to the more defensible Malamocco on the lido.

The metropolitan of the Christians had also fled mainland Aquileia and established Grado as his seat. He became known as the patriarch of Grado, and he built the basilica of Santa Eufemia there in the sixth century. Torcello's basilica of Santa Maria Madre di Dio was begun in 639.

Nominal ties with Constantinople continued for several centuries. Eighth-century dukes in Malamocco were often removed in violent factional strife. Only eight times in the first three centuries were the dukes chosen peaceably, usually from the Particiaco, Candiano, and Orseolo families. All other changes were violent.

When the Carolingians attempted to conquer Italy, the settlements on the lagoons asserted their autonomy. In 810, Charlemagne's son Pepin tried to conquer the lagoons, but he met the determined opposition of the men from Malamocco, assisted by a Byzantine fleet. By mid-century, both Carolingians and Byzantines recognized that the lagoons were autonomous; they had become a cushion between the western and the eastern empires. Their duke (pronounced doge on the lagoons), a genuine representative of local autonomy, moved his center from Malamocco to the Rialto, seat of the bishopric of Olivolo. Now the settlements on the lagoons began to bear the name Venice. In 828, two Venetians transferred the relics of Saint Mark the Evangelist from Muslim Alexandria to the Rialto. Their placement in a new ducal chapel legitimized the doge, but civil strife 150 years later would damage his chapel.

Doge Pietro II Orseolo (r. 991-1009) established his authority over the upper Adriatic by leading a naval demonstration to Istria and Dalmatia in the year 1000. This doge also made treaties with all the Muslim powers of the Mediterranean literal and achieved recognition from both western and Byzantine emperors. Doge Domenico Contarini (r. 1042-1071) confirmed ducal authority by initiating the reconstruction of the ducal chapel, which became the basilica of San Marco, housing the relics of the evangelist. Each new doge at his election was acclaimed by all the people, and lauds were sung in his name in the basilica of San Marco. Eleventh-century doges, however, continued to bear Byzantine titles.

In the tenth and eleventh centuries, judges drawn from among the better class (maiores) assisted the doge in his curia. The local neighborhoods maintained their own bridges, wells, shorelines, and night watches. With Doge Domenico Selvo (r. 1071-1084), a circle of the leading men dominated the popular assembly (arengo). They represented the collective will; they elected the doge, whom they usually chose, during the twelfth century, from the Falier or Michiel family. About 1143, Venice became a commune, led by the doge and a committee of judges known as the sapientes. But the popular assembly took matters into its own hands in 1172 and assassinated Doge Vitale II Michiel on his return from an unsuccessful punitive expedition against Constantinople. Leading merchant aristocrats reestablished order and elected their own Sebastiano Ziani as doge. They also replaced the popular assembly with a "great council," whose members included only the important families, officeholders, and former officeholders of the commune. The six sapientes (ducal councillors) became the "little council." Each doge after 1192 was required to take an oath of office (promissio ducale), which increasingly limited the ducal powers.

The doges of the early Venetian commune were remarkably strong leaders. Doge Enrico Dandolo led the commune in accepting the invitation of Flemish crusaders to participate in a crusade. This Fourth Crusade climaxed in 1204 with the capture of Constantinople and the beginning of Venice's overseas colonial empire. In the first half of the thirteenth century, the doges codified the laws of Venice.

Venetian interests in the eastern Mediterranean increased greatly during the thirteenth century, when Venice waged two wars with its commercial rival, Genoa. At home, the government became more rational. The organs of the commune formed a pyramid, with the general assembly at the base. Above it, the great council held the most power, electing all officials of the government, passing laws, and sitting in judgment on civil matters. A new council, called "the Forty" (quarantia), assumed responsibility for legal appeals, prepared the agenda for the great council, and controlled finances and the coinage. Later in the century, the sixty men who supervised commerce, naval, and foreign affairs were organized as the senate (consilium rogatorum or consiglio dei pregadi). When appropriate, the Forty and the senate acted jointly.

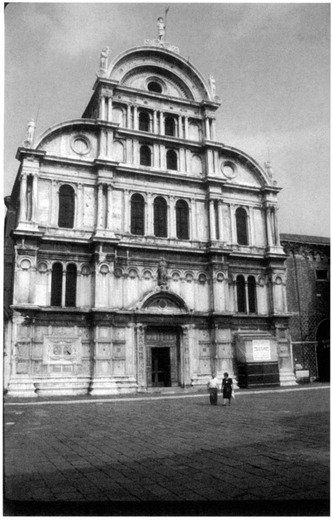

Church of San Zaccaria, Venice. Photograph courtesy of Christopher Kleinhenz.

Above these councils sat the ducal council or signoria, which included the doge, his six councillors, and the three heads of the Forty. They initiated governmental activities and officiated during crises, but they also had to obey the other councils. Most magistrates held office for one year or two, except for the doge, who held office for life. The doge presided over all the councils, providing continuity for the commune. The doge was head of state, but he was an elected leader and was restrained by the prohibitions specified in his oath of office. On completion of their terms, the doge and all other officials were subject to detailed examination of their work in office by the public prosecutors (avogadori de' comun) and subject to punishment if they had misused their office. A doge's heirs were responsible for his acts. Elected officials continued to multiply in the thirteenth century as the state became more influential in the lives of its citizens.

It is estimated that by the end of the thirteenth century, 100 public officials were elected annually by the great council, comprising varying numbers of patricians. In 1297, Doge Pietro Gradenigo led the commune to adopt new legislation, the Serrata ("closing"), which defined the membership of the great council. Members of the council, descendants of members, and men who held office in the commune were accepted. After the Serrata, membership in the great council defined a family as a member of the Venetian ruling class, the patriciate, the nobility. Only patricians could hold high office.

Two conspiracies called this reform into question. First, certain commoners under Marino Boccono disputed the reforms, but Boccono was hanged in 1300. More serious was the conspiracy of 1310, led by three patricians—BajamonteTiepolo, Marco Querini, and Badoero Badoer. They organized a three-pronged military assault against the center of government, the Piazza San Marco. However, Doge Gradenigo, who had received a warning, defeated the insurgents with the assistance of loyal patricians and workers from the arsenal. When Tiepolo's standard-bearer was struck by a mortar dropped from a window, he and his forces retreated to their palaces. Querini was killed; Badoer was captured and executed. But because Tiepolo was very popular and because both his grandfather and his great-grandfather had been doges, the commune sentenced him to perpetual supervised exile. To enforce this sentence leniently and to suppress any further plots, the commune created a special "council of Ten." Its members were elected annually from the great council and could act secretly and quickly. Their ability to act decisively made them one of the most important organs of the commune in later centuries.

Citizens of Venice, who were not enrolled in the patriciate, staffed the civil service from the fourteenth century on. One of them was grand chancellor to assist the doge. In the second half of the thirteenth century, the great council recognized the existence of many craft guilds. These checks and balances characterized the commune of Venice and ensured its stability.

During the fourteenth century, Venice was challenged by wars with Ferrara and with the king of Hungary, by insurrections in Crete against Venetian rule, and by two more wars with the Genoese. The Scaligeri despots of Verona and the Carrara of Padua in turn challenged Venetian domination of the rivers emptying into the lagoons. Also during this century, flooding from high tides threatened the lagoons in 1314, 1342, and 1386. The bubonic plague struck Venice fiercely after a Venetian galley returning from the Crimea in the autumn of 1347 brought the black death. Venice suffered for eighteen months, losing perhaps three-fifths of its population. The plague struck again in 1350, 1382, 1393, and 1395. Despite these challenges, the government structure held firm.

The third war with Genoa (1350-1355) strained the resources of the commune, which was then led by the humanist Doge Andrea Dandolo, a friend of Petrarch's. Marino Falier, the next doge (r. 1354-1355), although an experienced administrator and admiral, attempted to overthrow the aristocratic councils of Venice and become sole ruler. When his conspiracy was discovered by the ducal councillors, he was beheaded at the Giant's Staircase in the palace of the doges.

Twenty-three years later, Venice endured the most extreme challenge to its independence since Charlemagne—its fourth war with Genoa (the war of Chioggia, 1378—1381). Following the peace of Turin, Venice survived to limp back to mercantile and political strength, but Genoa lost its independence. In the 1390s, when the Carrara of Padua again threatened Venice, the commune allied itself with Gian Galeazzo Visconti to defeat the Carrara. Venice took Padua and executed its rulers. As a result, Venice added Padua, Vicenza, and Verona to its dominion in 1404-1406. Thus began the mainland extension of the Venetian state.

Seaborne commerce caused the growth of Venice. Early residents of the lagoons caught fish, hunted waterfowl, and collected the salt evaporating along the Adriatic, which they exchanged for products of the mainland. By the tenth century, Torcello in the lagoons was an important Adriatic seaport. The Lombard and Carolingian rulers in Pavia bought incense, silks, and spices from the merchants of the lagoons, who "neither sowed nor reaped and bought all their grain from others." Little documentation survives to describe this early Venetian trade.

Regular contacts were maintained between the Rialto and Constantinople throughout the early centuries, while Venice remained subject to the eastern Roman empire. The emperors attempted to suppress Christians' trade with Muslims in time of war. Venetian fleets assisted the Greeks against the Muslims on the Adriatic in the ninth and tenth centuries, when Muslim fleets attempted to close the Adriatic and even pillaged Grado on the lagoons. In 992, the Byzantine coemperors Basil II and Constantine VIII granted Venice relief from the special port taxes in the Sea of Marmara, although the Venetians were expected to abide by other Byzantine laws.

Relations between the ducal family and the Byzantine imperial house became closer in 1102, when the son of Doge Pietro Orseolo II married the niece of Emperor Basil II, and when doge Domenico Selvo (r. 1071 — 1084) married Theodora, the sister of emperor Michael VII. She scandalized the Venetians by her fastidious cleanliness, her use of a fork to convey food to her mouth, and her perfumes.

In 1082, Emperor Alexis I Comnenus granted the Venetians exemption from all tolls in Byzantine ports. They also obtained a protected quarter in Constantinople itself and trading privileges in the Byzantine seaports on the Aegean and Ionian Seas. In return, Venice allied itself with Byzantium to defend Byzantine Durazzo against their common enemy, Robert Guiscard. With these privileges, Venetian merchants had an enormous economic advantage over all other foreign traders and over the Byzantines themselves. Much of the Venetians' commercial profit came from their business in Romania (the Greek east). From this time, Byzantines began to depend on Italian sea power, rather than on their own war fleets, and the Greeks were forced to recognize the relative autonomy of the lagoons.

Venetian overseas trade increased greatly during the crusades, 1095—1291. Fleets from Venice assisted the crusaders at the conquest of Haifa in 1100 and at Sidon in 1110. A Venetian fleet defeated a large Egyptian fleet in the waters off Ascalon in 1123 and assisted in the capture of Tyre the next year. Conse-quently, the Latin kings of Jerusalem granted Venetians special quarters in the crusader cities. Venetian merchants concentrated their Syrian-Palestinian business in Tyre but also had privileges in Acre, Jaffa, and Ascalon. The Christian lords of Syria granted Venetians some privileges in the northern Syrian seaports where the Pisans and Genoese were more strongly entrenched.

Venetians also traded with Egypt during the crusades, as they had done for centuries. Crusading warfare interrupted this trade whenever Venetian fleets sailed to assist the Latin kingdom of Jerusalem, but the profits to be made in the markets of Alexandria and Damietta attracted the Latins again as soon as peace returned. Unlike Constantinople or the seaports of the crusading states, the Egyptian ports did not offer extraterritorial privileges to the Venetians during the twelfth century. Venice probably had no permanent settlement in Egypt until the thirteenth century. Venetians could, however, travel and do business there. Saladin's successor al-'Adil, in 1208, granted men of Venice two marketplaces in Alexandria where they could conduct business, drink wine, and eat pork. Subsequent commercial treaties in 1238, 1254, and 1264 further defined Venetians' privileges in Egypt, and the commune posted a consul there to represent transient Venetian merchants before Egyptian authorities.

The Venetian trading pattern during the crusading centuries revealed the realities of medieval commerce. Before the compass and the cog came into general use in the late thirteenth century, shipping across the Mediterranean was usually confined to the warmer months. Voyages to and from the Aegean, Constantinople, and the crusader states would be accomplished in one season, but the longer voyage to and from Egypt usually required an overwinter stay. The heavier cargo (grains and metals) traveled on round ships propelled by sails; but the smaller, shallower galleys with oars and sails carried luxury products of small volume. Merchants would form partnership contracts (commenda or sea loans) for a single voyage, and the profits would be divided at the end of the trip. Some families held property in common, and their overseas business would continue for several years before settlement. A senior merchant residing in Venice would send a junior partner overseas to carry out the contract. Venetian agents overseas, who lived in Venetian compounds in foreign ports, assisted in the business negotiations. As many as 10,000 Venetians were residing in Constantinople in 1171.

What were the products of this overseas trade? Venetians carried from Europe its woolen cloth, lumber, wooden utensils, and metals (copper, tin, iron), and also some bullion. Although the doges prohibited the slave trade across the Mediterranean, Venetians did participate in it. In Constantinople they purchased local luxury products: silk fabric, ivories, ornamental metalwork, enamels, and mosaics; in Syria-Palestine, they bought sugar, dates, raw silk, and fine cotton fabrics. Into the crusader states and Egypt came luxury spices (galingale, nutmeg, cloves, rhubarb), pearls and other precious stones, silks, camphor, and musk from the far east. After the Fourth Crusade, the luxuries from farther Asia were loaded onto Venetian ships in the Black Sea, Cilician Armenia, the Turkish ports of western Anatolia, and Egypt. Egyptian markets also furnished raw cotton while Constantinople, Crete, and the Black Sea provided foodstuffs (wheat, barley, oats, millet, cheese, and sugar).

Products were priced by agreements between the parties in the local money of each seaport. Byzantine hyperpera served markets of Romania; gold bezants (solidi) of the Latin kingdom of Jerusalem served the crusader states; and Egyptian bezants circulated along the Nile. At home, Venetians used money struck in other Italian communes until the last decades of the twelfth century. The first truly Venetian coin, a penny (denarius), was struck in the 1170s; the more successful, larger, purer grosso appeared in 1194. During the thirteenth century, the grosso achieved ever greater acceptance in the eastern Mediterranean. Gold coins of Florence and Genoa began to supplant the Byzantine gold hyperpera in the west after 1252. Not until 1284 did Venice strike its gold ducat at the same weight and fineness as the florin. In the fourteenth century, this gold ducat achieved international acceptance. By 1400, the Venetian gold ducat, famous for its stable weight and purity, had conquered all the markets in the eastern Mediterranean

Each Venetian overseas compound (fondaco) was fortified. There the traveling merchant could stay for a time, store his merchandise, and enjoy the company of his fellow Venetians. These compounds usually also had bake ovens and a chapel, and they retained the standard for Venetian weights. Sometimes Venetian holdings extended outside these compounds, as at Tyre and Constantinople.

Constantinople was the largest of the twelfth-century Venetian colonies, owing to the extraordinary privileges Venetians held in Byzantium. In 1119, the emperor John Comnenus refused to renew the Venetians' privileges; consequently, the Venetian fleet plundered Greek ports in the Ionian and Aegean, forcing the emperor to renew the privileges in 1126. Although the privileges were renewed again in 1148, the Byzantines were beginning to play off the Genoese and Pisans against the Venetians. In Constantinople, Venetians, Pisans, and Greeks rioted against the Genoese in 1162. Nine years later, the Byzantines suddenly imprisoned all Venetians in Constantinople and confiscated their goods. In 1182, the emperor proceeded similarly against the Pisans and Genoese, whereupon Venice once more sought its former privileges from the Greeks. Byzantium gave Venice some satisfaction in 1183 and 1187, and still another emperor reconfirmed the Venetians' privileges in 1198.

Relations between Venice and Romania changed dramatically with the Fourth Crusade, 1201-1204. Flemish and French knights came to Venice in 1201 to obtain transportation on a crusade. Venice agreed to provide ships, transportation, and food for 33,500 men and horses for one year, in return for 85,000 silver marks. The Frankish crusaders who gathered in Venice in 1202, however, were far fewer in number than had been anticipated. The Venetians had prepared 50 galleys and 450 transports for the anticipated crusade to be led by Boniface of Montferrat. To pay the cost of the fleet, the crusaders agreed to assist Venice against its Dalmatian possession, Zara, which had revolted. Enrico Dandolo, the Venetian doge, then took the cross along with many other Venetians. After subduing Zara, the crusaders received a new proposal from a Greek prince, Alexios. He offered to provide more troops, supplies, and money to the crusaders and to unite the eastern and western churches if they placed him on the imperial throne of Constantinople, removing a usurper. After much discussion, the leaders agreed to redirect the crusade to Constantinople. They sailed. On arriving at Constantinople, the crusaders were jeered, but they did enter the city. The usurper fled, and the crusaders installed young Alexios and his blind father on the imperial throne. When the Greeks would not honor Alexios's promises to assist the crusade, the crusaders circumspectly withdrew from the city. Yet another Byzantine prince deposed and murdered young Alexios and his father and took the throne. At this, the crusaders massed their forces and took the city by storm in April 1204. Afterward, they sacked the city for three days. The crusaders' cruelty and devastation in Constantinople have been long remembered by the Greeks.

After the sack, the crusaders and Venetians carried out the terms of their previous agreements. The booty was collected, and three-fourths of the first 200,000 marks of booty was given to the Venetians to pay for their fleet while the Franks received the other fourth. The rest of the booty they split evenly. Twelve electors then chose Baldwin of Flanders as the future Latin emperor of Constantinople, according to the contract, and the office of Latin patriarch of Constantinople was awarded to Venice. A committee of twelve Franks and twelve Venetians produced the "treaty of partition" (October 1204), which divided the vast Byzantine empire according to an agreed-on ratio: one-fourth of the Greek lands to the Latin emperor, three-eighths to the Franks, and three-eighths to the Venetians. The committee awarded the Venetians the Thracian coast and the inland area as far as Adrianople; much of mainland Greece, including the Morea (Peloponnese); the Aegean islands; the Ionian islands; and the Dalmatian coast, with its islands. However, except for Constantinople, all these remained in Greek hands. As Venetians took possession of some of these lands, the Venetian colonial empire was born.

From 1205 to 1261, the Latin emperors in Constantinople relied on Venetian sea power and financial strength for their existence. In Constantinople, Venice regained its special commercial and legal privileges and the Venetian podestà was second only to the Latin emperor. Venetians composed half of the imperial council. Venetian ships could sail freely into the Black Sea. They temporarily took possession of the ports on the Sea of Marmara and the straits of the Dardanelles. Venetian naval strength predominated in these waters during the Latin empire.

Outside the immediate environs of Constantinople, the Venetians did not extend their control over all places awarded them by the treaty of partition. A fleet from the commune took Ragusa, Durazzo, the Ionian Islands, Moron, and Coron in the Morea; but the Greek despot of Epirus captured Durazzo, Corfu, and Cephalonia within a decade. Venice never held the inland Morea but tenaciously kept and fortified its southwest promontories, Modon and Coron.

The commune of Venice purchased the large island of Crete and rights in Negroponte (Euboea) from the marquis of Montferrat in 1204. Military expeditions and permanent military colonists from Venice established the authority of Venice in Crete against challenges from Genoese pirates and local Greek lords. Crete became the largest and most populous Venetian colony. Negroponte also came under Venetian influence, since the three gentlemen from Verona who were Montferrat's vassals needed the advice, credits, and naval protection of Venice.

Venetian citizens, with their own privately financed and privately equipped expeditions, took possession of certain other Aegean islands. Marco Sanudo conquered Naxos and its neighboring islands in the Cyclades beginning in 1207. He and his heirs became independent dukes of the archipelago. Sanudo awarded Andros to his cousin Marin Dandolo. The Ghisi brothers, Andrew and Jeremiah, captured the northern Sporades (My konos, Tenos, Skyros, Skiathos, and Scopelos) in 1207. Filocalo Navigaioso held Lemnos as megaduke under the Latin emperor. Jacopo Viaro held Cerigo, and Marco Venier held Cerigotto. These men were independent lords in the Aegean, but they were also citizens of Venice. Recent scholarship has demonstrated that not until the fifteenth century did Venetian noblemen begin to control the islands of Anaphe, Astypalaea, Carpathos, Chios, Cyprus, Seriphos, Thera, and Therasia.

With these holdings, Venetian strengm and influence prevailed along the routes from Venice to Constantinople, Syria, and Egypt. Genoa challenged the Venetian colonial empire in four wars. In the first war (1257-1270), the Genoese and Venetians fought over the markets of Acre and over control of the sea lanes. Venice won victories at Acre in 1258, at Settepozzi in 1262, and at Trapani in 1266. Peace was made in 1270 when King Louis IX of France intervened to provide transportation for the forces of his last crusade.

During these hostilities, in 1261, Genoa, in the treaty of Nyrnphaion, agreed to assist Michael VIII Palaeologus, the Greek emperor of Nicaea, in recovering Constantinople. The Latin empire fell to the Greeks the same year, when one of Michael's lieutenants took Constantinople in the absence of the Venetian fleet. Genoese ships then protected the restored Byzantine empire and gained the Venetians' former profitable commercial privileges. Michael, mistrusting the Genoese, readmitted Venetians to Constantinople in 1269, but he did not reaffirm all their former privileges in the city.

After 1261, the Venetians trailed the Genoese in exploiting the Black Sea. Venetian merchants did establish themselves in the Crimea and the Sea of Azov, and after 1291 in Trebizond. Marco Polo traveled from Venice to China via the Black Sea and stayed for twenty years before returning to Venice. His return to Venice was rerouted owing to Venice's second war with Genoa. During this war (1294-1299), Genoese fleets defeated the Venetians off Lajazzo in Asia Minor and off Curzola in the Dalmatian coast. Even the Byzantines joined the Genoese against Venice, but again the results of the contest were inconclusive.

In the fourteenth century, Venetian wealth from its colonial empire increased greatly. The senate dominated commercial policy. The commune added a permanent presence in Constantinople and market privileges in the Crimea, Tana, and Trebizond in the Black Sea and, late in the century, on the island of Corfu. The independent Venetian fiefdoms in the Aegean depended more and more on the Rialto for protection from the threats of Turkish pirates.

Venice maintained a mercantilist policy toward its colonies. The commune siphoned all seaborne trade from the colonies on Venetian vessels to Venice and insisted that certain quantities of grain be shipped annually to Venice to feed the inhabitants. The Venetian commune monopolized the production of salt on the lagoons, Istria, and the Adriatic coast and became the sole supplier for the northern Italian mainland. In the fourteenth century, Venetian ships brought salt from the Aegean to satisfy this demand.

During the fourteenth century, the governments of the Venetian colonies mirrored that of Venice itself. Each colonial executive was elected by the great council of Venice from the Venetian patriciate. He served for two years, together with other, lesser elected Venetian officials. Crete had its duke, Modon and Coron had their castellan, Alexandria had its consul, and Negroponte had its bailiff, as did Constantinople. Each elected colonial governor had the duty of enforcing civil and criminal law and justice, assisted by Venetian officials and by a council representing the resident colonists.

Competition from Genoese, Greek, and Turkish pirates at sea and from predatory land powers created unsafe conditions for Venetian commerce, although commerce became increasingly profitable in the fourteenth century, when it was bound by regulations enforced by Venetian civil servants. At mid-century, Venice experienced an economic crisis brought on by the black death and by the indecisive third war with Genoa (1350-1355), which was expensive in terms of both men and money. This was followed by a thirty-year truce between Venice and Genoa; but the truce in turn was followed by the decisive fourth war with Genoa (the war of Chioggia, 1378-1381). The fourth war began when the two republics clashed over Tenedos, guarding the Dardanelles, and also over the lucrative markets in the Black Sea. Venetian fleets under Carlo Zeno and Vettor Pisani fought against Genoese fleets throughout the Mediterranean, but Pisani was imprisoned by the commune because he had lost a battle with the Genoese at nearby Pola in Istria. The Genoese, assisted by their allies on the mainland, besieged Venice itself and took Chioggia at the southern edge of the lagoons. A Genoese fleet patrolled the Adriatic, cutting off the Rialto from its food supply. With famine threatening, the desperate commune released the popular Vettor Pisani from prison. He created a new fleet of small boats manned by enthusiastic Venetian craftsmen and shopkeepers, who maneuvered through the shallow lagoons to besiege the Genoese in Chioggia. At this critical moment, Carlo Zeno's fleet returned to the lagoons from successful raids against the Genoese. With Zeno's blockade by sea and Pisani's blockade on the lagoons, the Genoese were forced to surrender. The resulting peace of Turin, mediated by Amadeus VI of Savoy (the "Green Count"), divided the points of colonial conflict between Genoa and Venice.

Next, Venice faced the growing threat of Turkish sea power, as the Ottomans gained more territory in Thrace and Thessaly to complement their control of the interior of Asia Minor. At the end of the fourteenth century, Tamerlane burned Tana on the Sea of Azov and temporarily destroyed all Venetian access to the northern silk route. Venetian commerce was to grow during the Renaissance in spite of these challenges.

The people of Venice were bound together by their physical setting and the common need to protect themselves in an unfriendly environment. Not only the rivers but also the sea flooded them, and earthquakes shook them on their small islands at the upper reaches of a salt sea. Their position, however, was easily defensible. Only twice before 1400 did they come under enemy attack: in 811 from the Carolingians and in 1380 from the Genoese. Each time the Venetians emerged victorious.

Who was a Venetian? He or she had a Venetian father and lived on the lagoons. Persons who had a Venetian father in a Venetian colony were also recognized as Venetians. To be Venetian conferred distinct commercial advantages. Before 1204, Venetians could buy and sell in the Byzantine empire without paying the heavy Byzantine commercial dues. In the Latin empire of Constantinople, Venetians were guaranteed special privileges. During the fourteenth century, only Venetians could bid at auction to own and outfit a great galley in the annual convoys from Venice

The patricians of Venice directed the city throughout its history. A tradition from the Renaissance, recently questioned by historians, names twelve founding families, the "apostolic families," who continued to lead Venice for centuries. The earliest patricians of Venice were known as tribunes, local officials enforcing law and order under the exarchs of Ravenna. The early doges came from this class and were assisted by it. Some patrician families died out, and other families took their place. The Serrata of 1297 separated the members of the great council from other Venetians, and yet that council accepted new families during the fourteenth century, particularly during the war of Chioggia. One must accept the fluidity of society in medieval Venice.

Feudalism did not exist in Venice. A society policed by men on horseback could not exist in the islands on the lagoons, where everyone moved by boat. Yet some trappings of feudal society were copied by Venetians in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries: feudal manners, and the enjoyment of jongleurs, romances, and jousts. Venetian landholding in the lagoons was never subject to enfeoffment. The limited land available was bought and sold, mortgaged and rented. By the tenth century, if not before, the major activity of Venetians would be trading down the Adriatic, across the sea to Byzantium and the Muslim world. This urban mercantile society differed sharply from the agrarian-based feudal society of mainland Italy.

The lite of a Venetian patrician followed a regular pattern. In his youth, he learned the techniques of business from a master of the abacus. In his teens, he would accompany a mature merchant on trading voyages. Venetian merchant manuals, which have survived from the fourteenth century, demonstrate that the young merchant collected information on the "conversion of the bewildering variety of medieval weights, measures, and moneys and information on local conditions, on quality standards, and on common frauds." As an adult, he would travel frequently with partnership contracts for other merchants and would also participate in the government of the commune. Domenico Gradenigo made thirteen commercial voyages abroad between 1206 and 1224. In old age, the merchant usually remained at home, entrusting his investments to younger men. In extreme old age, the Venetian would retire to a monastery.

Venetian women seldom appeared in the medieval sources. Girls were educated in convents. Their fathers arranged their marriages and calculated the dowries, which included money and credits, household goods, and clothing. Some articles of apparel were passed down from generation to generation. Spiritual, ill-favored, or unlucky girls became nuns, and their fathers gave their dowries to the convents. The Benedictine convent of San Zaccaria, next to the ducal palace, played a significant role in politics because daughters of the most noble patricians entered it. Widows sometimes operated on their own authority without the permission of a male relative. A widow's dowry and inheritance were hers to invest in local business, real estate, and the overseas trade, although male relatives often guided a woman's business. Medieval Venetians sometimes married foreign women: Doge Pietro IV Candiano (d. 796) married Waldrada, the sister of Marquis Ugo of Tuscany; Doge Otto Orseolo (d. 1032) married the sister of King Stephen of Hungary; Doge Pietro Ziani (d. 1229) married Costanza, the daughter of King Tancred of Sicily. Venetians living in overseas colonies often married local women. Gasmules, the sons of Venetian men and Greek women in the east, had special status in Venetian law.

Beginning in the fourteenth century, wealthy nonnoble Venetians who did not engage in mechanical trades were called cittadini. Native cittadini who were trained as lawyers and notaries could aspire to positions not open to patricians in the ducal chancery and the law courts. The most important position was grand chancellor to the doge. Cittadini and patricians enjoyed the same commercial privileges at home and in the colonies.

Venetian industrial production expanded in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, as foreign markets and immigration from the mainland created a greater demand. Craftsmen and shopkeepers produced and sold items for local consumption: woolen cloth, shoes, weapons, and household utensils. Carpenters and stonemasons built the palaces, bridges, and warehouses of the city. Shopkeepers sold wine, meat, vegetables, and other foodstuffs. Craftsmen built ships both in private shipyards and in the government-controlled arsenal. This arsenal, first mentioned in 1104, and enlarged in 1303 and 1325, produced and outfitted large ships lor the commune.

Craftsmen and cittadini organized into confraternities (the scuole and the guilds) for religious observances and mutual aid. By 1300, the four larger nonprofessional confraternities were recognized as scuole grandi. Craftsmen also organized into craft guilds with charters approved by communal officials. By 1300, more than 100 craft guilds were known in Venice. However, in Venice—unlike Florence and nearby Padua—these craft guilds did not participate in the government of the commune but rather were regulated by it. Each guild elected its own gastald, chosen from the ranks but approved by the authorities. No guilds were formed by the most numerous of the city's workforce, the seamen; or by the most influential businessmen, the international merchants. The rich merchants had no need to form guilds, because they controlled and staffed the commune's offices to benefit their own commercial interests. Since cittadini, craftsmen, and shopkeepers were encouraged to rise to prominence, each in his own niche, and since patrician authorities promoted peace and trade that benefited all, the city of Venice rarely experienced social upheavals after 1300.

Venice, like the rest of Europe, experienced great population growth in the 250 years before the black death of 1347—1349, Its population, estimated at 160,000, placed Venice among the largest cities of Europe just before the black death. But that sudden catastrophe killed perhaps three-fifths of the population of the lagoons within eighteen months. Afterward, the city began to recover. Immigrants came from the mainland when local harvests were poor, attracted by Venice's reputation for feeding its people with grain imported from overseas. Lombards, Tuscans (especially men of Lucca and Florence), Dalmatians, Germans, Hungarians, and Jews swelled the population. In the fourteenth century, citizenship was made available to foreign-born persons residing in Venice if they had lived in the city for twenty-five years and did not engage in the mechanical trades, or if they married Venetians. A few of these new wealthy citizens were granted membership in the patriciate at the critical time of the war of Chioggia.

Venetians joined together in support of their church. By the twelfth century, they were organized into seventy parishes. The Venetian church leaned toward Rome and accepted the Roman theology, liturgy, iconography, and system of church government. After the translation of the remains of Saint Mark the Evangelist to Venice in the ninth century, Mark became the spiritual father of the lagoons, a symbol of the unity of Venice. As England had Saint George and Rome had Saint Peter, so Venice had Saint Mark. The basilica of Saint Mark was the private chapel of the doge, where state ceremonies began. The primicerio of this palatine chapel was the leading ecclesiastic in Venice, politically more important than the patriarch of Grado, titular head of the Venetian ecclesiastical establishment. Under Enrico Dandolo (the uncle of Doge Enrico Dandolo), patriarch from c. 1135 to 1187, the patriarchal palace was permanently transferred from Grado, which was frequently flooded, to the parish of San Silvestro near the Rialto. Patriarchs belonged to Venetian patrician families and often, but not always, supported the policies of the doges. Six bishops served under the patriarch of Venice. The bishop of Castello (earlier known as bishop of Olivolo) had jurisdiction over the Rialto but was himself subordinate to the patriarch. Until the late thirteenth century, all abbots, bishops, and other church dignitaries belonged to patrician families.

Monasteries on the lagoons perpetuated the rule of Saint Benedict and were under the authority of the local bishops. The monastery of San Giorgio Maggiore, on its own island, held first place among Venetian houses. It was founded in 982 by the entire population of Venice, headed by the doge, patriarch, and bishops. By 1300, the lagoons had sixty Benedictine houses.

Because the Venetian church and state were so closely intertwined, the papal reforms of the eleventh and twelfth centuries did not take hold on the lagoons; instead, local ecclesiastics carried through their own reforms. Cluny, Citeaux, and the Pre monstratensians established no more than a weak presence. The patriarch and local bishops led the fight in Venice against heresies; not until 1289 did an emaciated papal Inquisition appear there. The Venetian clergy were not hostile to the commune; they supported it. Writing to Pope Innocent III during the Fourth Crusade, a Venetian cleric said, "We Venetians always work for the honor of God and of the holy Roman Church." The ducal oaths of office supported the premise that God and the church joined in the Venetian state. The doge, rex sacerdotus, with powers from God, approved the election of church officials and invested them with their property.

In the thirteenth century, Venetian society welcomed the Franciscans and Dominicans. Doge Iacopo Tiepoio donated land to build the great Dominican church of Santi Giovanni e Paolo, where doges, admirals, and captains would be buried. The great Franciscan church, Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, was built on land donated by the Badoer family. Venetian laymen welcomed the friars and willed bequests for them. Dominicans began to occupy the patriarchal and episcopal seats of Venice in the late thirteenth century; among these Dominicans was Tolomeo da Lucca, bishop of Torcello from 1318 to 1327, theologian, historian, and confessor of Saint Thomas Aquinas.

Venetian was the language most commonly spoken on the lagoons, but it appeared in written form only occasionally from the eleventh century on. It was not the language of culture, science, business, or government. Priest-notaries drafted documents in Latin for the church, private business, and government. Proximity to Bologna brought legal scholars to Venice, and patricians sent their sons to Bologna for legal training. The earliest written law codes, drafted in Latin before 1250, recorded the local customary criminal, maritime, and civil law. The civil law of Venice compiled for Doge Iacopo Tiepolo in 1242 continued to be the basic law of Venice until 1797. Venetian jurists added interpretations, drawn from opinions of Italian glossators such as Odofredus. Venetians also developed their own historical tradition; and most histories were written in Latin. When the Venetian Marin Sanudo Torsello (1270—1343) wished to propagandize for a new crusade, he wrote in Latin. The scholarly doge Andrea Dandolo (d. 1354) composed his chronicles in Latin.

Yet Venice, like other Italian cities and the Venetian colonies in the thirteenth century, accepted French as a literary language. The Venetian troubadour Bartolomeo Zorzi wrote in French, as did the engaging chronicler Martino da Canal. Marco Polo's Relazioni, taken down in a Genoese prison by a Pisan, appeared first in French.

With Dante, however, Venetians, like other Italians, began to accept Tuscan as a literary language. Petrarch lived in Venice for many years. The commune gave him a house on the Riva degli Schiavoni, and he offered to bequeath his library to the city. Although the library was dissipated, Petrarch's example and his friendship with Doge Andrea Dandolo and Andrea's grand chancellors Benintendi dei Ravagnani (d. 1365) and Rafaino Caresini (d. 1390) established humanistic ideals in the Venetian patriciate. Consequently, Venice assumed a unique identity among the cities of northern Italy, because the city joined its local traditions with influences from both the Latin west and the Greek east.

See also Amadeo VI, Count of Savoy; Aquileia; Dandolo Family; Falieri, Marino; Genoa; Grado Patriarchate oft Orseolo Family; Petrarca, Francesco; Polo, Marco; Ptolemy of Lucca; Tiepolo Family; Torcello; Venice: Art; Visconti Family

LOUISE BUENGER ROBBERT

Arnrnerman, Albert J. Probing the Depths of Venice." Archaeology, July-August 1996, pp. 38-43.

Brown, Horatio F. Studies in the History of Venice, 2 vols. New York: Dutton, 1907.

Dotson, John E. Merchant Culture in Fourteenth-Century Venice: The Zibaldone da Canal. Binghamton, N.Y.: Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies, 1994.

Lane, Frederic C. Venetian Ships and Shipbuilders of the Renaissance. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1934.

—. Venice, a Maritime Republic. Baltimore, Md., and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973.

Lane, Frederic C., and Reinhold C. Mueller. Money and Banking in Medieval and Renaissance Venice, Vol. 1, Coins and Moneys of Account. Baltimore, Md., and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1985.

McNeill, William H. Venice, the Hinge of Europe, 1081—1797. Chicago, 111., and London: University of Chicago Press, 1974.

Oliphant, Mrs. The Makers of Venice: Doges, Conquerors, Painters, and Men of Letters. London and New York: Macmillan, 1893.

Queller, Donald E„ and Thomas F. Madden. The Fourth Crusade: The Conquest of Constantinople, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1997.

Zorzi, Alvise. Venice, the Golden Age: 697-1797, trans. Nicoletta Simborowski and Simon Mackenzie. New York: Abbeville, 1980.

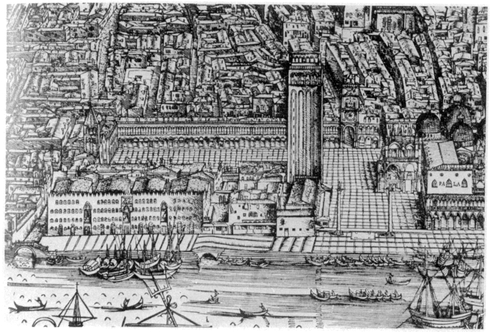

The urban geography of Venice as we know it today dates from the twelfth century. Over the course of some four centuries the small, swampy islands of the Venetian archipelago had been gradually drawn together through a Herculean process of land reclamation to which the early documents give eloquent testimony. The earliest known plan of Venice, of c. 1346—which is preserved in the Cronaca magna in the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana—is based on a twelfth-century exemplar. It already presents a compact landmass, traversed by a broad S-shaped canal, that speaks of the formed city. Beginning in the thirteenth century, the formation of the city entered a new phase as the state began to play an increasingly larger and more directive role, ultimately assuming a substantial part of the financial burden in the impressive process of fusion that transformed the scattered islands into a functioning urban unit.

The major focus of Venice's first phase of urban development was the defining of a civic center. Shortly after the mid-twelfth century, in the 1160s or 1170s, on a site at the southern edge of the city that had previously contained a fortified enclave, a regularized civic center began to be constructed. It included residences for high-ranking administrators, an extended palace structure (palatium communis) that housed the doge's residence together with law courts and meeting rooms, and a grand new church of San Marco to shelter the relics of Venice's patron saint, Mark. Under Doge Sebastiano Ziani (r. 1172-1178), the land in front of San Marco was acquired for the state and established as a great open space with roughly the dimensions of Piazza San Marco as it stands today. In Venice, the term piazza is reserved for Piazza San Marco.

Two events can serve as anchor dates for the formative development of the civic center. On one side is the establishment, first recorded in 11 52, of the opus ecclesie sancti Marci, the office of works of the new church of San Marco. This office, soon designated as the procuratia di San Marco, would eventually expand into a key administrative and financial bureau for the city as a whole. Marking the finalization of the conception of the civic core was the paving of the great open space that defined the civic center, Piazza San Marco, in the 1260s. In 1277, the state mint, the zecca, was moved to the civic center from the Rialto. thus concentrating the major government units at this central site. As a splendid urban scheme, the development of the Venetian civic center has been linked to the great imperial forums of ancient Rome and the antique forums and gathering places, still carrying the cachet of imperial rule, that remained extant in medieval Constantinople.

The art of medieval Venice has its first phase in connection with the building and embellishment of the structure that dominates the civic core, the church of San Marco. The traditional starting date for work on San Marco as we see it today—the third church on the site—is 1063, under Doge Domenico Contarini (r. 1043-1071) and hence referred to as the "Contarini San Marco." According to a cherished Venetian tradition, San Marco was modeled on the church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople; but in a pattern that was to stamp Venetian art for much of its history, San Marco represents a creative amalgam of western and eastern elements. The plan brings together aspects of the Roman basilica and the Greek-cross plan. Specific aspects of the construction—e.g., the type of the crypt and the character of the brickwork (thick bricks joined by thin layers of mortar)— separate San Marco from Byzantium and further connect it to the west. To be considered in conjunction with San Marco is the testimony to indigenous building provided by a group of churches on the nearby islands of Torcello and Murano. Having escaped later rebuilding campaigns, these structures bring one close to the early stages of church building in Venice. The church of Santi Maria e Donato on the island of Murano, substantially of the twelfth century, is basilican in plan with a superb hexagonal apse and handsome exterior brick patterning. The cathedral of Torcello, Santa Maria Assunta, founded in the seventh century and rebuilt in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, stands as a starkly impressive brick basilican structure. Also on Torcello is the small central-plan church of Santa Fosca, largely of the eleventh century with some twelfth-century additions, constructed on an octagonal plan and elegant in its exterior brickwork.