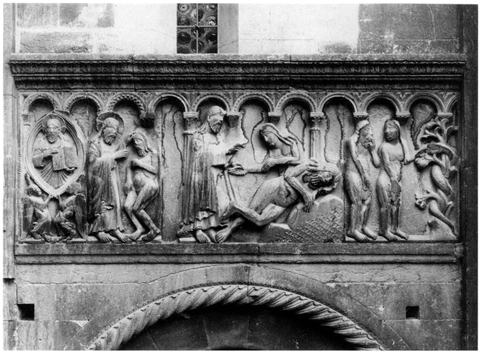

Wiligelrnus of Modena, Creation of Adam, Creation of Eve, Original Sin. Modena, duomo. Photo: © Alinari/Art Resource, N.Y.

The Waldensians, also called the Poor of Lyon, were a heretical sect founded by the merchant Valdes and were probably the largest medieval heterodox group.

Valdes was a wealthy merchant and usurer of Lyon who experienced a powerful conversion c. 1173. While listening to a jongleur sing of Saint Alexis, an early Christian who had turned away from great wealth to take up a life of poverty and penance, Valdes was suddenly seized by remorse for his own sins and by a realization that his wealth was a hindrance to his salvation. He had discussions with a theologian and contemplated biblical and patristic texts that he had hired priests to translate; all this convinced him that he should pursue the evangelical life of preaching and poverty embraced by the apostles and the early church. After providing for his wife and daughters, Valdes distributed his money to the poor and began to preach and beg in the environs of Lyon. He soon attracted a following who also went about preaching repentance; they called themselves "the poor."

These activities brought Valdes and his followers into conflict with the clergy of Lyon: they were violating church laws that forbade laymen to preach without the permission of the clergy, and they seemed to be usurping the authority of the city's churchmen. Moreover, their emphasis on apostolic poverty was causing laypeople to criticize wealthy clerics. Within a short time, the archbishop forbade the Waldensians to preach. Valdes at first ignored the archbishop's order but then decided to seek approval from Pope Alexander III. In 1179, he appealed to the pope at the Third Lateran Council. Alexander's decision did not resolve the situation, however: he approved the Waldensians' vow of poverty but prohibited them from preaching without the approval of the local clergy.

From this point on, relations between the Waldensians and the clergy of Lyon worsened. The clergy came to fear that Valdes's followers would be influenced by the heretical teachings of the Cathars; also, zealots claiming an affiliation with Valdes's group created more friction. New attempts by the archbishop to silence the Waldensians brought a staunch refusal from Valdes, who reportedly quoted Saint Peter; "It is better to obey God than men" (Acts 5:29). In 1182, a new archbishop promptly excommunicated the group and drove them from his archdiocese. They quickly spread through southern France and northern Italy, winning many followers. Pope Lucius III condemned them in 1184, but their numbers continued to grow. By the turn of the thirteenth century, Valdes's followers had become well established in France and Italy and were beginning to appear in Germany.

The Waldensians' belief centered on a determination to follow all the commands and precepts given by Christ to his disciples, even those traditionally reserved to the clergy. When clergymen objected, the Waldensians accused them of contradicting scripture and rejected their authority. Some Waldensians, including Valdes, hoped for a reconciliation with the church. Others contended that the Roman church had lost its authority when it embraced wealth in the time of Constantine, and that Waldensians were called by God to reconstitute the apostolic life which the Roman church had abandoned. They developed a "remnant theology"—an image of a few faithful Christians preserving the true faith of the apostles in secret during the centuries between Constantine and Valdes. In place of the Roman clergy, they created their own lay ministry, the "perfect," pious men and women who renounced possessions and marriage to attend to the faithful. Their function was to hear confessions, celebrate the eucharist, preside at baptisms and weddings, and above all preach to the faithful and evangelize among unbelievers. On scriptural grounds, Waldensians rejected Purgatory, indulgences, and the cult of the saints, and they declared legal proceedings, oaths, capital punishment, and warfare to be sinful.

Valdes probably died during the first decade of the thirteenth century. Even before his death, serious tension had developed among his followers; the French and Italian branches of the Waldensians formally split in 1205. This had little effect on the sect's growth, however, because the Waldensians ecclesiastical organization was so loose. The attempts of the Roman church to combat the spread of Waldensian beliefs also had little impact until the emergence of the papal Inquisition in the 1230s. Then, however, the church made rapid gains. Although the Inquisition was aimed against Cathars in particular, it often caught Waldensians as well. By the end of the thirteenth century, Waldensians had been driven out of most urban centers. They remained active in remote areas up to the Reformation, when many of them joined Protestant denominations. The Waldensians of the Piedmont survived into modern rimes and were granted equality with Catholics in 1848.

See also Alexander III, Pope; Councils, Ecclesiastical; Heresy and Religious Dissent

THOMAS TURLEY

Berkhout, Carl T., and Jeffrey B. Russell. Medieval Heresies: A Bibliography, 1960-1979. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies, 1981, pp. 53-61.

Gonnet, Jean. Le confessioni di fede valdesi prima delta Riforma. Turin: Claudiana, 1967.

Heresy and Authority in Medieval Europe, ed. Edward Peters. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1980, pp. 139 164.

Lambert, Malcolm. Medieval Heresy, 3rd ed. Oxford: Blackwell, 2002, pp. 70-96, 158-189.

Selge, Kurt-Victor. Die ersten Waldenser. Berlin: De Gruyter, 1967.

Thouzellier, Christine. Catharisme et valdeisme en Languedoc a la fin du XIIe et au debut du XIIIe sièele, 2nd ed. Louvain: Editions Nauwelaerts, 1969.

Thouzellier, Christine, and Amedeo Molnár. Les Vaudois au Moyen Âge. Turin: Claudiana, 1974.

Walter VI of Brienne (d. 1356) was the son of Jeanne de Chatillon and Walter V (d. 1311), count of Brienne and duke of Athens. Walter VI was unable to hold the duchy of Athens after his father's death; he continued to claim the title but fled to the Angevin court at Naples. There he reached maturity and worked in the service of King Robert. Throughout his life, Walter continued, unsuccessfully, to press his claims to the duchy of Athens while accepting numerous signorial and military appointments.

Walter is best-known for his involvement with Florence. In 1325, he served the city for two and a half months. Later, in 1342, the Florentines commissioned him to command their forces, then fighting Pisa for possession of Lucca. Walter accepted and was soon proclaimed signore of Florence for life. He was initially championed by the politically dominant patricians, who hoped that he would preserve their power against pressures from a politically weakened nobility and a disenfranchised working class. The nobility implored Walter to repeal the Ordinances of Justice of 1293, which restricted their political activity. Walter did allow the ordinances to fall into abeyance, but he did not repeal them, and he soon lost his support among the nobility. He tried to broaden his support by cultivating lesser Florentine guildsmen and laborers, but in the end he also failed to please them. On Saint Anne's day, 26 July 1343, the Florentines revolted against him. After his expulsion, Saint Anne's day was declared a public holiday.

Walter died fighting against the English at Poitiers.

See also Angevin Dynasty; Florence; Ordinances of Justice; Robert of Anjou

ROGER J. CRUM

Becker, Marvin. "Walter VI of Brienne to 1343." Dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, 1950.

—, Florence in Transition, 2 vols. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1967-1968.

Villani, Giovanni. Cronica di Giovanni Villani, 4 vols., ed. Francesco Gherardi Dragomanni. Florence: Coen, 1844-1845.

Medieval Italy had more systems of weights and measures and more individual units than any other country in western Europe except the Holy Roman empire. The major reason was that Italian metrology developed without any reference to a commonly accepted set of national standards. In England, the Winchester standards and later the London standards served as prototypes for bringing thousands of local units into eventual alignment. In France, the weights and measures of Paris occupied this position. But Italy, with its many kingdoms, duchies, communes, republics, and the like, was never able to attain any level of metrological standardization outside the confines of severely restricted, small, independent political jurisdictions. Generally, not until the mid-nineteenth century—and as a practical matter not until unification was achieved in 1871 —were Italian weights and measures given a totally uniform national character. Then, it was the metric system, not a conglomerate of units rehabilitated from the past, that finally accomplished the task.

Although no precise boundary can be drawn, weights and measures in medieval Italy tended to be divided into a northern and a southern system. The northern system extended from the famous urban centers of Tuscany to central Italy; the southern system included all of southern Italy and the islands of Malta, Corsica, Sardinia, and Sicily. Within these two zones, all weights and measures had either local, regional, or interregional applications. Local units (comune, comunitativo, da piazza, or di città) used in urban and rural settings dominated Italian metrology. There were several hundred thousand such units, and they rarely had any use outside their immediate environs. Approximately 100 regional units (delict commissione or legale) were found in the two major systems. Although they rarely crossed the lines of demarcation between north and south, they did provide a modicum of standardization within their respective zones. It was the interregional units that enabled Italy to have at least a semblance of a national system. They were the backbone behind the commercial revolution after c. 1000.

To further complicate matters, among all these weights and measures there were thousands of special units—agricultural (agrimensorio or da terra); architectural (architettonica); scientific (geometrico); medical, pharmaceutical, and commercial (commercio or mercantile); manufacturing (da fabbrica); industrial and trade (da muratore or manuale); forest (da foreste); maritime (della marina, geografico, or marittimo); textile (da cotone, da lana, da panno, da seta, da tela, da tessitore, or della stoffe); horticultural (da frantoio); viticultural (da vigne); fishing (dapesci), and business—and these bore no relationship to one another either in application or in inter- and intraunit proportions. Hundreds of other units were used specifically for taxes (censuario), precious gems, gold, silver, and scale weighings (da bilancia or da stadera). There were special product and quantity units (for example, balla, ballone, bariglione, dozina, and tonnellata); there were many units that had multiple names and usages (for example, cantaio, carara, carica, carrata, centinaio, coppo, decimo, decina, grannotto, grosso, lira, migliaio, mina, misura, ottavo, passetto, peso, quarta, rubbio, salma, spazzo, staiolo, staro, tavola, trappeso, and vignale); and there were numerous diminutives (for example, baletta, bariletto, brentina, centesimo, decimillesimo, granottino, millesimo, quartarella, and sedicesimo) that had no definite sizes or dimensions.

This chaotic state of affairs certainly was a radical departure from the uniform, integrated, and standardized system of weights and measures that Italy had enjoyed from the later centuries of the Roman republic to the declining years of the Roman empire. Roman weights and measures had been the "metric system" of the ancient world. But Italy suffered the same fate as the rest of western Europe when the Roman empire collapsed in the wake of the barbarian invasions after the fourth century. Centralized governments fell, and the cohesive forces of a standard language, law, military structure, coinage system, and weights and measures vanished from the Mediterranean world. Out of the ashes rose the native metrological systems of Europe. Italy was part of this new order.

Despite these grave problems, Italy's interregional standards were used extensively at home and abroad, and they constituted the metrological basis of most important financial and commercial transactions. Following are the principal weights and measures of medieval Italy. Unless otherwise noted, the various weights and measures were used throughout Italy, Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica, and Malta. Since so many different standards served as prototypes, the metric equivalents are given only as ranges over which they fluctuated (U.S. equivalents, though not stated, are calculable from the metric values).

Linear measurements. For linear measurement, there were seven major units. The braccio ("arm") was the premier industrial and mercantile measure of length, found primarily in northern and central Italy. It was defined originally, in the early Middle Ages, as the length of the two arms extended when measured from the tips of the middle fingers and was reckoned generally between 5 and 6 piedi ("feet"), but each piede, usually of 12 once ("inches"), varied from 0.223 to 0.649 meter; thus the braccio could range from 1.115 to 3.894 meters.

The canna was the principal unit for textiles, agricultural land divisions, construction, architecture, and forestry. It was usually divided into a diverse number of braccia, palmi ("palms"), piedu or once (approximately 0.996 to 7.851 meters); it was sometimes used synonymously with the pertica ("perch," "rod," or "pole") or trabucco.

Among the smaller linear units were the punto ("point'), piede, and palmo. The punto consisted of 12 atomi (about 0.00143 to 0.005846 meter) and equaled 1/12 oncia. The piede consisted generally of 12 once (about 0.223 to 0.649 meter), but there were numerous variants ranging from 6 5/6 to 32 4/5 once. The palmo also consisted of 12 once (about 0.1250 to 0.2918 meter), but it had no established set of submultiples.

The largest interregional standard was the miglio ("mile"). This was originally based on the Roman mile of 8 stadii (furlongs) of 1,000 geometrical paces totaling 5,000 feet (about 1.481 kilometers). However, by the later Middle Ages, a number of important regional standards gained dominance. The miglio was generally divided into an irregular assortment of corde ("cords"), canne, palmi, passi ("paces"), perticbe, braccia, trabucchi, orpiedi, and it varied from about 1.482 to 2.519 kilometers.

Measurements of capacity. Capacity involved the greatest number of interregional standards because of its obvious importance to national and international trade. The barile ("barrel") was the major measure for liquids and dry products. This unit was borrowed from the French during the High Middle Ages. It was divided regionally into an irregular number of rotoli, caraffe, fogliette, pinte ("pints"), cannate, quartucci, misure ("measures"), some, zucche, ambole, boccali, quarte ("quarts"), fiaschi ("flasks"), amole, rubbi, quarteroni, quartare, libbre ("pounds"), libbrette ("light pounds"), or secchie varing in size from about 0.117 to 2.248 hectoliters. For wine, the boccale was the most important measure throughout Corsica and northern and central Italy; it varied from about 0.041 to 3.044 liters and was divided into once, quarte, mezzi, terzetti, fogliette, rotoli, zaine, quartini, mezzette, or quartucci. In northern and north-central Italy, the brenta, usually divided into boccali, was the major unit for wine; it varied from about 0.475 to 1.233 hectoliters. In central and southern Italy, the caraffa was the major unit for wine; it was calculated in weight content by once (about 0.322 to 6.341 liters). The pinta mentioned in all these units normally consisted of 2 boccali and varied in size from about 0.893 to 2.262 liters.

For grain and other dry products the moggio, quartaro, quartarolo, quartuccio, soma, and staio were paramount. Although these measures could all be applied to liquids and were used occasionally to determine surface or volume specifications, their principal use was for selling or bulk-rating agricultural produce. The moggio varied from about 1.393 to 6.633 hectoliters and was usually divided into sacche ("sacks"), staia, quarte, quartini, or scodelle. The quartaro, normally consisting of 4 meta, varied from about 0.046 to 0.220 hectoliter. The quartarolo and quartuccio were divided into a wide variety of local measures; the quartarolo varied from about 0.581 to 36.807 liters, and the quartuccio from about 0.355 to 6.135 liters. The soma was generally divided into tomoli, quartari, staia, emine, or sacche and varied from about 1.456 to 2.112 hectoliters. The staio, normally divided into mine or quarte, varied from about 0.091 to 2.945 hectoliters.

Measurements of area. In medieval Italy, agricultural land areas were measured using the giornata more than any other superficial (surface) unit. Originally the giornata was the amount of land covered by a man and draft animal in the course of one workday (the English acre). During the High Middle Ages and the late Middle Ages, it had regional variations ranging from about 0.090 to 0.450 hectare and was usually reckoned in square passi, palmi, tavole, staia, or canne.

Measurements of weight. For weights, there were nine principal standards. The largest was the cantaro, a hundredweight for bulk rating wholesale shipments of goods carried long distances overland or by sea to foreign markets, especially to the hundreds of fondacos or factories established by Venice, Genoa, and other Italian cities in foreign urban centers along the Palestinian and North African coastlines. It varied generally from 100 to 250 libbre (about 30.12 to 339.29 kilograms), its exact weight depending on the various local standards for the libbra. The carato ("carat") was the smallest. A weight of 4 grani ("grains"), it was used for gold, silver, and precious gems, and it varied from about 1.770 to 2.135 decigrams.

In between these two extremes were the denaro, a weight of 24 grani (about 1.075 to 2.432 grams), generally synonymous in name with the dramma ("dram") and in size with the scrupolo ("scruple"). The dramma was a weight of 72 grani (about 1.671 to 3.595 grams), generally consisting of 3 denari or scrupoli equal to 1/8 oncia. The scrupulo was a weight of 24 grani (about 0.891 to 1.198 grams) equal generally to 1/3 dramma or 1/24 oncia. The rotolo was generally considered equal to 1/100 cantaro (about 0.475 to 1.019 kilograms).

The standards on which the above weights were based were the grano, oncia, and libbra. The grano consisted of 24 granottini or granotti ("light grains," about 0.000045 to 0.000055 kilogram) and equaled 1/24 denaro. The oncia generally equaled 1/12 libbra (about 0.0245 to 0.0431 kilogram). The 'libbra was the foundation stone for every weight system. Most cities had two libbre—a light (piccolo or sottile) and a heavy (grosso). Both libbre were often used interchangeably with the lira (pound). Each libbra normally consisted of 12 once (about 0.239 to 0.980 kilogram), but intraunit proportions of 8, 13 7/8, 14, 15, 16, 18, 24, 28, 30, 32, and 36 once were not uncommon.

Most European countries that did not have an axis around which to formulate a national system of weights and measures eventually opted for metric uniformity during the nineteenth century. Italy was no exemption. But during the Middle Ages, despite the formidable obstacles presented to business and financial operations by the metrological vagaries described above, Italy created and sustained the medieval world's greatest commercial empire. That perhaps is the ultimate testimony to the applicability and adaptability of these metrological units to the Italian mercantile machine.

RONALD EDWARD ZUPKO

slberti, Hans-Joachim von. Mass und Gewicht: Geschichtliche und tabellarische Darstellungen von den Anfdngen bis zur Gegenwart. Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1957.

Byrne, Eugene H. Genoese Shipping in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries. Cambridge, Mass.: Medieval Academy of America, 1930.

Clarke, F. W. Weights, Measures, and Money of All Nations. New York: Appleton, 1876.

Edler, Florence. Glossary of Medieval Terms of Business: Italian Series 1200-1600. Cambridge, Mass.: Medieval Academy of America, 1934.

Kelly, Patrick. The Universal Cambist and Commercial Instructor, 2 vols. London: Printed for the Author, 1821.

Kennelly, Arthur E. Vestiges of Pre-Metric Weights and Measures Persisting in Metric-System Europe, 1926-1927. New York: Macmillan, 1928.

Kisch, Bruno. Scales and Weights: A Historical Outline. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1965.

Kula, Witold. Measures and Men, trans. Richard Szreter. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1986.

Lane, Frederic C. "Tonnages, Medieval and Modern." In Venice and History: The Collected Papers of Frederic C. Lane. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins Press, 1966.

Nicholson, Edward. Men and Measures: A History of Weights and Measures: Ancient and Modern. London: Smith, Elder, 1912.

Pegolotti, Francesco Balducci. La pratica delta mercatura, ed. Allan Evans. Cambridge, Mass.: Medieval Academy of America, 1936.

Zupko, Ronald Edward. Italian Weights and Measures from the Middle Ages to the Nineteenth Century. Memoirs, 145. Philadelphia, Pa.: American Philosophical Society, 1981. (Bibliography of European sources.)

—. "Weights and Measures, Western European." In Dictionary of the Middle Ages, Vol. 12. New York: Scribner, 1989, pp. 582-596.

—. Revolution in Measurement: Western European Weights and Measures Since the Age of Science. Memoirs, 186. Philadelphia, Pa.: American Philosophical Society, 1990. (Bibliography of European sources.)

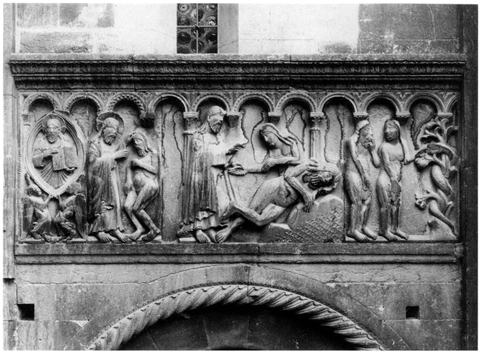

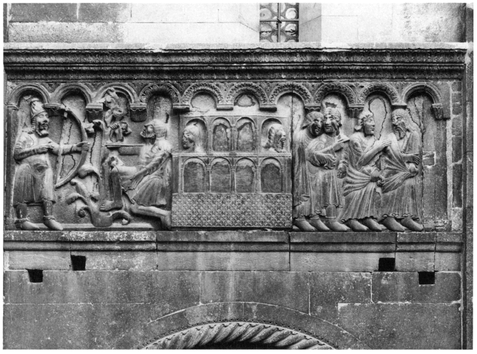

Wiligelmus (Guglielmo, Wiligelmo; fl. c. 1099—c. 1120) is often considered the first great Italian sculptor. His reliefs on the facade of Modena cathedral are among the first important sculptural programs of northern Italy, as part of the early development of Romanesque sculpture. His identity as the creator is known from an inscription held by the figures of the prophets Enoch and Elijah: Inter scultores quanto sis dignis more—Claret scultura nunc Wiligelme tua ("How much honor you deserve among sculptors is now shown by your sculpture, Wiligelmo"). Wiligelrnus's oeuvre has been identified at Modena and elsewhere through stylistic comparisons with these prophets, carved from the same block as the inscription.

Wiligelmus's principal work is the sculptural assemblage on the west facade of the cathedral of Modena, presumably executed c. 1106-1110, including the inscription plaque; four reliefs from Genesis; two reliefs of genii with overturned torches; numerous capitals and decorative reliefs; and the program of the central portal, containing an elaborate scroll motif and twelve reliefs of prophets. The present placement of some of the reliefs is the result of changes made to the facade in the late twelfth century by the Campionese masters, who added the lateral portals and relocated the first and fourth reliefs from Genesis above them. Some scholars hold that these reliefs were created as part of liturgical furnishings for the interior of the cathedral (Quintavalle 1964-1965), but the evidence suggests that they were originally intended as part of a sculptural program decorating the facade.

The four reliefs from Genesis flanking the central portal serve as a monumental introduction to the cathedral and constitute the first large-scale frieze devoted exclusively to biblical subjects. The general themes are the creation, the fall, and the promise of salvation as revealed in the flood. The frieze concludes with the ark as the ship of salvation—an Old Testament prefiguration of salvation and the mission of the church. Labors of the Progenitors and Cain and Abel Offering to God, which flank the main portal, present a lesson to the faithful about giving the fruits of one's labors to God (and the church). Textual similarities between the inscriptions and the liturgical drama Ordo representa cionis Ade suggest that performance and image were intended to work together to educate audiences about the roles of church and faithful in the history of salvation. Wiligelmus's Genesis frieze should thus be seen as an important early example of the development of large-scale didactic Romanesque sculptural programs.

Wiligelmus's figures are conceived as bold, massive, vital forms of great monumentality and plasticity. They convey an impressive sense of weight, as seen in the angels holding God's mandorla and Abel's slumping body in Cain Killing Abel. Figures emerge from the relief plane and fully occupy the space that is allotted to them, even bursting into the frame of the plaque (e.g., Enoch and Elijah). These forms have large heads, hands, and feet; broad faces with lead-inset eyes; hair articulated by long, wavy parallel strokes; and beards punctuated with drill holes. Solemn, full of gravitas, these bodies express the narrative action with clear, bold gestures. Wiligelmus animates his figures with palpable human expressions (especially notable is the anguish on Cain's face as he is killed by Lamech). Most of these sculptures make prominent use of inscriptions, either identifying figures or including more extensive biblical, liturgical, or secular texts; the inscription plaque held by Enoch and Elijah is an example.

Numerous sources and models for Wiligelmus's style have been suggested, including ivory, metalwork, and manuscripts as well as early Romanesque sculpture in Aquitaine and Bari. The most direct and most apparent source of inspiration is Roman sculpture. Local, provincial Roman works clearly provided models for several of the reliefs in Modena. The genii with overturned torches and the arrangement of the prophets Enoch and Elijah on the inscription plaque are clearly derived from Roman sarcophagi. Wiligelmus's access to these sources can be explained by Relation translationis corporis sancti Geminiani (Account of the Translation of the Body of Saint Geminianus), which mentions the miraculous discovery of a quarry of building materials, presumably the necropolis or other parts of the Roman city of Mutina (Modena). Wiligelmus adopted not only formal arrangements of figures from these Roman sources but also the sense of solidity and gravitas that distinguishes his sculptures. Furthermore, the obvious source of inspiration for the arrangement of the frieze around the central portal is the Roman triumphal arch. This suggests a certain conscious use of antique forms to connote both the venerable antiquity of Modena and the triumph of the church.

In addition to the program at Modena, Wiligelmus appears to have worked at the cathedral in Cremona before the earthquake of 1117. The four large prophets from the jamb of the portal are stylistically analogous to his work at Modena. Fragments of a frieze from the cathedral of Cremona, clearly modeled after Wiiigelmus's reliefs in Modena, appear to have been executed by his workshop. Wiligelmus apparently directed a large workshop that trained numerous sculptors who continued his work at Modena and carried his style elsewhere. The two lateral portals at Modena—Porta della Pescheria (north, by the Master of the Artu) and Porta dei Principi (south, by the Master of San Geminiano)—are products of the school of Wiligelmus. These two portals follow Wiiigelmus's basic scheme from the west portal, but with smaller, less massive, though more lively figures. The Porta dei Principi is the earliest example of the northern Italian form of a two-story porch-portal supported by lions or atlantes bearing columns. That this form developed in the context of Wiiigelmus's workshop further indicates his seminal role in the development of northern Italian Romanesque sculpture.

Additional sculpture by the workshop of Wiligelrnus can be found at the Benedictine abbey of Nonantola, the cathedral of Piacenza, the Pieve di Quarantoli, and the Cluniac abbey of San Benedetto Polirole. The most noteworthy pupil of Wiligelrnus is Master Nicholaus.

See also Cremona; Modena; Nonantola; Piacenza

Wiligelrnus of Modena, Creation of Adam, Creation of Eve, Original Sin. Modena, duomo. Photo: © Alinari/Art Resource, N.Y.

Wiligelrnus of Modena, The Killing of Cain, The Ark, The Debarkation from the Ark. Modena, duomo. Photo: © Alinari/Art Resource, N.Y.

SCOTT B. MONTGOMERY

Crichton, George Henderson. Romanesque Sculpture in Italy. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1954.

Francovich, Geza de. "Wiligelmo da Modena e gli inizii della scultura romanica in Francia e in Spagna." Rivista dell'Istituto Nazionale di Archeologia e Storia dell'Arte, 7, 1940, pp. 225-294.

Frugoni, Chiara. Wiligelmo: Le sculture del duomo di Modena. Modena: F. C. Panini, 1996.

Gandolfo, Francesco. "Note per una interpretazione iconologica delle storie del Genesi di Wiligelmo." In Romanico padano, romanico europeo, ed. Arturo Carlo Quintavalle. Parma: Artegrafica Silva, 1982, pp. 323-337.

Lanfranco e Wiligelmo: Il duomo di Modena (Quando le cattedrali erano bianche), 3 vols., ed. E. Castelnuovo, V. Fumigalli, A. Peroni, and A. Settis. Modena: Panini, 1984.

Porter, Arthur Kingsley. Romanesque Sculpture of the Pilgrimage Roads, 10 vols. Boston: Marshall Jones, 1923. (Reissue, New York, 1966.)

Quintavalle, Arturo Carlo. La cattedrale di Modena: Problemi di romanico emiliano, 2 vols. Modena: Editrice Bassi, 1964-1965.

—. Da Wiligelmo a Nicola. Parma, 1966.

—, ed. Wiligelmo e la sua scuola. Florence: Sadea-Sansoni, 1967.

—. Romanico padano, civiltà d'occidente. Florence: Marchi e Bertolli, 1969.

—. "Piacenza Cathedral, Lanfranco, and the School of Wiligelmo." Art Bulletin, 55, 1973, pp. 40-57.

—. Wiligelmo e Matilda: L'officina romanica. Milan: Electa, 1991.

Salvini, Roberto. Wiligelmo e le origini della scultura romanica. Milan: Aldo Martello, 1956.

—. La scultura romanica in Europa. Milan: Garzanti, 1963.

—. II duomo di Modena e il romanico nel modenese. Modena: Cassa di Risparmio di Modena, 1966.

Wiligelmo e Lanfranco nell'Europa romanica. Atti del Convegno, Modena, 24-27 ottobre 1985. Modena: Panini, 1989.

William (r. 1111-1127) was the son of Roger Borsa and became duke of Apulia on Roger's death. The anarchy and disorder that had prevailed in southern Italy during the reign of his father became even worse during William's rule. Diminished and dismembered, the duchy was now a collection of independent regions. William died childless. The most direct heir was Bohe mond, the son of Bohemond I of Antioch (1058-1111); but Roger II of Sicily (1105—1154), William's cousin, was quick to assert his control over the area and annex it to Sicily. The papacy reacted promptly, organizing a coalition of southern Italian nobles to inhibit this union, but this response was not effective.

See also Bohemond of Taranto; Normans; Roger II; Roger Borsa

ANTHONY P. VIA

Norwich, John Julius. The Other Conquest. New York: Harper and Row, 1967.

William I (1120—May 1166, r. February 1154—1166) was the 5on of King Roger II of southern Italy and Sicily (whom he succeeded), and Albiria of Castile. Thanks in part to a prejudiced but influential account in a twelfth-century chronicle, History of the Tyrants of Sicily, by the so-called Hugo Falcandus, William I has often been referred to as "the Bad." Loud (1999) suggested that "the Unlucky" might be a more appropriate sobriquet, and Norwich (1970) offered "the Sad" as another possibility.

William I inherited the kingdom created by his celebrated father. This inheritance included a nobility discontented with the rapid changes in royal policy regarding the mainland. At least two rebellions occurred during William's reign, in 1155-1156 and 1161. A number of principal lords were exiled for their opposition and remained a significant threat. William's chief minister, Maio of Bari, aroused much consternation and was eventually overthrown and murdered by the rebels. William I also faced threats from foreign powers, especially from the Byzantines, against whom he battled in 1155. In 1158-1160, he lost the North African holdings that had been won by his father.

William I did not receive adulation—the sources reserve that for his father—but his reign was not a total disaster. Accounts of William's cruelty and paranoia notwithstanding, he did achieve some success in securing peace treaties with Venice, Genoa, the Byzantine empire, and the papacy.

See also Hugo Falcandus; Normans; Roger II; William II

JOANNA H. DRELL

Chalandon, Ferdinand. Histoire de la domination normande en Italie et en Sicile, 2 vols. Paris: A. Picard et Fils, 1907. (Reprint, 1991.)

The History of the Tyrants of Sicily by "Hugo Falcandus," trans, and ed. Graham A. Load and Thomas Wiedemann. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1998.

Loud, Graham A. "William the Bad or William the Unlucky? Kingship in Sicily, 1154-1166." Haskins Society Journal, 8, 1999, pp. 99-113.

Matthew, Donald. The Norman Kingdom of Sicily. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Norwich, John, Julius. The Kingdom in the Sun, 1130—1194. London: Longman, 1970.

William II (1154-1189, r. 1166-1189) succeeded his father, William I, as king of southern Italy and Sicily. He was twelve when he assumed the throne, and until he reached his majority, his mother, Margaret of Navarre, served as regent. William II is frequently referred to as "William the Good"—in comparison with his father, who is called "William the Bad." William II was celebrated in Dante's Paradiso (Canto 20) and Boccaccio's Decameron (4.4 and 5.7).

William II was a strong ruler who did little to diminish the model of monarchy established by his predecessors, especially his grandfather, Roger II. William II's reign was notable for his foreign policy. He married Joan, the daughter of King Henry II of England, in 1177. Also in 1177, he negotiated a truce with Frederick I Barbarossa, who had recently been defeated by the Lombard League at Legnano (1176). William II's most enduring accomplishment was contracting a marriage in 1186 between Frederick I Barbarossa's son Henry (later Emperor Henry VI Hohenstaufen) and William's aunt and heir, Constance (daughter of Roger II). This marriage not only gave the Hohenstaufen an undeniable connection to the southern Italian realm but also produced one of the most important medieval rulers: Frederick II. William II also undertook several military campaigns against the Byzantines and the Muslim North Africans. He launched a massive attack on the Byzantines in 1185 and captured Thessalonica, but his forces were defeated and dispersed before they reached Constantinople.

Another impressive accomplishment of William II was his founding of the extraordinary Benedictine monastery at Monreale in Sicily in 1174. The decoration and architecture of the cathedral at Monreale cathedral are regarded as a monument to the multicultural influences that characterized the kingdom of southern Italy and Sicily: Norman, Byzantine, Arab, and Italian.

See also Boccaccio, Giovanni; Constance; Dante Alighieri; Frederick I Barbarossa; Frederick II Hohenstaufen; Henry VI Hohenstaufen; Monreale; Normans; Roger II; William I

JOANNA H. DRELL

Chalandon, Ferdinand. Histoire de la domination normande en Italic et en Sidle, 2 vols. Paris: A. Picard et Fils, 1907. (Reprint, 1991.)

Demus, Otto. The Mosaics of Norman Sicily. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1950.

The History of the Tyrants of Sicily by "Hugo Falcandus," trans, and ed. Graham A. Loud and Thomas Wiedemann. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1998.

Kitzinger, Ernst. Mosaics of Monreale. Palermo: S. F. Flaccovio, 1960.

Loud, Graham A. "William the Bad or William the Unlucky? Kingship in Sicily, 1154-1166." Haskins Society Journal, 8, 1999, pp. 99-113.

Matthew, Donald. The Norman Kingdom of Sicily. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Norwich, John, Julius. The Kingdom in the Sun, 1130—1194. London: Longman, 1970.

William III (late twelfth century) was crowned king of Sicily either shortly after the death of his brother Roger III in late December 1193, while their father King Tancred (Tancred of Lecce) was yet alive, or else after Tancred's death in February 1194; in this matter, as in others, the sources for his poorly documented reign are neither unanimous nor altogether trustworthy. The earliest of William's few known charters is dated June 1194. As he was only a child when he became king, a regency was exercised for him by the queen mother, Sibylla of Acerra. Her government, largely a continuation of Tancred's, prepared for and then resisted the invasion of Henry VI until November 1194, when Henry had conquered most of the kingdom and was now outside the walls of Palermo. In the ensuing negotiations for a surrender, Sibylla obtained Henry's promise to grant William (or perhaps herself; again, the sources differ) the county of Lecce and to make him prince ofTaranto, undertakings Henry seems to have honored. Henry's triumphal entry into the city on 20 November marks the official beginning of his reign; by then William's was already over.

In late December, Henry had William, Sibylla, and others politically close to them arrested and publicly condemned for treason. Their conspiracy against Henry has been widely considered a fabrication; its outcome was certainly convenient for him. The now proclaimed traitors were soon (early 1195) sent to confinement in Germany, along with various other captives (including William's three sisters and his sister-in-law, the princess Irene). William seems to have been separated from the rest en route and is said to have been kept in Hohenems castle in present-day Austria. He is also reported to have been blinded and, according to one chronicle (which is not always reliable), deprived of his penis; both mutilations are possible and would have served different though related ends. Pope Innocent III appealed for his release early in 1198, but William was not among the prisoners who were let go that year, and the presumption is that he was already dead.

See also Henry VI Hohenstaufen; Normans; Tancred of Lecce and Roger III, Kings of Sicily

JOHN B. DILLON

Zielinski, Herbert, ed. Tancreai et Willelmi III. regum diplomata. Codex Diplomaticus Regni Siciliae, Series 1(5). Cologne: Böhlau, 1982.

Csendes, Peter. Heinrich VI. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1993, pp. 146-156.

Jamison, Evelyn. Admiral Eugenius of Sicily: His Life and Work and the Authorship of the Epistola ad Petrum and the "Historia Hugonis Falcandi Siculi." London: Oxford University Press for the British Academy, 1957. (See especially pp. 103-105, 109-140, 155.)

Reisinger, Christoph. Tankred von Lecce: Normannischer König von Sizilien. Kölner Historische Abhandlungen, 38. Cologne: Böhlau, 1992, pp. 12-14, 178-183.

William Durandus (Guillelmus Duranti, Guillaume Durand; c. 1230 or 1231-1 November 1296) is called the Elder to distinguish him from a nephew with the same name. The elder William Durandus was born in Puimisson, near Béziers in Provence. We know practically nothing about his family or early life before his ordination as subdeacon in the cathedral of Narbonne c. 1254 and his enrollment in the list of canons at the cathedral of Maguelonne at about the same time. Not long after taking clerical orders, William began formal legal studies at the University of Bologna; he earned a doctorate in canon law there c. 1263. He may have lectured at the university before he became a papal chaplain and "general auditor" under Pope Urban IV (r. 1261-1264). Early in his long and increasingly difficult career in the service of the papal curia, William befriended the best-known canonist in Europe, Cardinal Henricus de Segusia (Henry of Susa), known as Hostiensis.

Under Pope Clement IV (1265—1268), William continued his service as papal chaplain and auditor. He also finished the first edition of his first publication, Aureum repertorium (c. 1264—1270), a short index and commentary on Gratian's Decretum (c. 1140) and on Pope Gregory IX's Liber extra (1234). Aureum repertorium was soon followed by William's massive and—during the medieval period—definitive textbook on procedural law, Speculum Iudiciale (c. 1271 — 1276). The enduring fame of this work earned William the nickname Speculator, by which he was commonly known during and after his lifetime.

In the summer of 1274, William attended the Second Council of Lyon and held the official title of peritus (theologian) for Pope Gregory X (1271-1276). William later assisted in the post-conciliar editing of the canons of the council, and some twenty years afterward he published the final version of In sacrosanctum Lugdunese concilium commentarius (c. 1293-1294), his long commentary on the council's decrees.

By 1279, William was ordained a priest and was made dean of the cathedral of Chartres by Pope Nicholas III (r. 1277-1280). In 1280, Nicholas appointed him rector et capitaneus generalis of a portion of the papal states (including a part of Tuscany and the diocese of Rieti). In 1281, the new pope, Martin IV (r. 1281-1285), added to William's official duties rule of the turbulent Romagna. From 1282 to 1286, William coordinated the war efforts of the papacy in the Romagna, leading the pro-papal Guelfs to a precarious interim victory over the Ghibellines.

In 1285, William submitted his resignation from the papal service to Pope Honorius IV (r. 1285-1287). Within a month, William was elected bishop of Mende in his native Provence by the cathedral chapter. He was consecrated bishop by the archbishop of Ravenna in 1286 but (inexplicably) remained in Rome for another five years before taking up residence in Mende in July 1291.

William's prolific literary production during his episcopacy demonstrates his conscientious application of his learning to pastoral care (not to mention his capability as an encyclopedic polymath). The works he published in this period include the following: Constitutiones synodales (c. 1292), a collection of statutes and instructions for the reform of the clergy of his diocese; Ordinarium (c. 1291-1293), a book regulating the liturgical services of the cathedral of Mende; his commentary on the Second Council of Lyon; Rationale divinorum officiorum (c. 1291-1296), a long allegorical commentary on the entire liturgy (including the mass, divine office, and church year); and Pontificate (Bishop's Book, c. 1293—1295), which provided rubrics and prayers for liturgical services performed only by a bishop. Modern scholarship has revealed that William's Rationale and Pontificale were two of the most important liturgical texts of the entire medieval period in Europe.

William had been a resident bishop for only four years when he succumbed to the persistent entreaties of his friend Benedict Gaetani, now Pope Boniface VIII (r. 1294-1303), to return to Rome and assume official duties in the papal states. In September 1295, William was appointed rector of the Anconian March and the Romagna, territories that were in a state of near-anarchy since the Ghibelline faction had mobilized itself for war with the Guelfs. William's command of the papacy's war effort failed, however, when he lost the city of Imola to the Ghibellines and presided over the defeat of a pro-papal Bolognese army in April 1296. By the end of the summer of 1296, William, who was by then in his sixties, seems to have had little if any official responsibility in the papal states. He continued to reside in Rome, where he died.

William Durandus the Elder was buried in the church of Santa Maria Sopra Minerva. A thirty-line epitaph praising his life and works was inscribed there in marble, possibly at the request of his nephew William Durandus the Younger, who succeeded him as bishop of Mende.

William Durandus. Hartmann Schedel, Liber chronicarum (Nuremberg Chronicle). Nuremberg: Anton Koberger, 1493, p. 216v.

There are numerous incunabula and early printed editions of Aureum repertorium super toto corpore iuris canonici, but as of the present writing there was no modern edition. Speculum iudiciale survives in more than 100 medieval manuscripts; there are numerous incunabula and early printed editions but (again as of this writing) no modern edition. A manuscript (possibly written or corrected by Durandus himself) of Constitutiones synodales was published in a diplomatic edition (Berthelé and Valmary 1905). The only known printed edition of In sacrosanctum Lugdunese concilium commentarius is that of 1569. The Pontificate was published in the magisterial edition of Andrieu (1940). The Rationale divinorum officiorum survives in hundreds of medieval Latin manuscripts, as well as numerous medieval vernacular translations; the first modern critical edition is Davril and Thibodeau (1995, 1998). Although a complete modern biography of Durandus has yet to be written, the bibliography of secondary sources is voluminous; selected references are listed below.

See also Boniface VIII, Pope; Clement IV, Pope; Gratian; Gregory IX, Pope; Gregory X, Pope; Honorius IV, Pope; Ho stiensis; Martin IV, Pope; Nicholas III, Pope; Urban IV, Pope

TIMOTHY M. THIBODEAU

Andrieu, Michel, ed. Le pontifical romain au Moyen-Age, Vol. 3, Le pontifical de Guillaume Durand. Studi e Testi, 88. Vatican City: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, 1940.

Aureum repertorium super toto corpore iuris canonici. Venice: Paganinus de Paganinis, 1496-1497.

Berthelé, J., and M. Valmary, eds. "Les instructions et constitutions de Guillaume Durand le Spéculateur," Academie des Sciences et Lettres de Montpellier: Memoires de la Section des Lettres, Series 2(3), 1905, pp. 1-148.

Davril, Anselme, and T. M. Thibodeau, eds. Guillelmi Duranti Rationale divinorum officiorum I—IV, V—VI. Corpus Christianorum, Continuatio Medieaevalis, 140 and 140A. Turnhout: Brepols, 1995; 1998. (At the time of the present writing, a third and final volume, Books VII VIII, was in press.)

In sacrosanctum Lugdunese concilium commentarius sub Gregorio X Guilelmi Duranti cognomento Speculatoris commentarius, ed. Simone Maiolo. Fano: Iacobus Moscardus, 1569.

Speculum iudiciale, illustration, et repurgatum a Giovanni Andrea et Baldo degli Ubaldi. Basel: Froben, 1574. (4 parts in 2 vols.; the best-known and most widely available text. Reprint, Darmstadt: Aalen, 1975.)

Balmelle, Marius. Bibliographic du Gévaudan, n.s., fasc. 3. Mende: n.p., 1966. (Pamphlet. Good though dated bibliography for the life and works of Durandus and his nephew.)

Boyle, Leonard. "The Date of the Commentary of William Duranti the Elder on the Constitutions of the Second Council of Lyons." Bulletin of Medieval Canon Law, n.s., 4, 1974, pp. 39-47.

Douteil, Herbert. Studien zu Durantis "Rationale divinorum officiorum" als kirchenmusiealischer Quelle. Kölner Beiträge zur Musikforschung, 52. Regensburg, 1969.

Dykmans, Marc. "Notes autobiographiques de Guillaume Durand le Spéculateur." In lus populi Dei: Miscellanea in honorem Raymundi Bidagor. Rome, 1972, pp. 121-142.

Faletti, Louis. "Guillaume Durand." Dictionnaire de droit eanonique, 5, 1953, pp. 1014-1075.

Gy, Pierre-Marie, ed. Guillaume Durand, évêque de Mende (v. 1230-1296): Canoniste, liturgiste, et homme politique—Aetes de la Table Ronde du CNRS Mende 24-27 rnai 1990. Paris: Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, 1992. (Collection of papers; at the time of its publication it represented the most up-to-date research on Durandus.)

Leclerq, Victor. "Guillaume Duranti, évêque de Mende, surnommé le Spéculateur." In Histoire Littéraire de la France, Vol. 20. Paris: Libraire Universitaires, 1895, pp. 411-480.

Ménard, Clarence C. "William Durand s Rationale divinorum officiorum'. Preliminaries to a New Critical Edition." Dissertation, Gregorian University (Rome), 1967. (Groundbreaking work that was the basis for a recently published edition of the Rationale.)

Thibodeau, Timothy M. "Enigmata figurarum: Biblical Exegesis and Liturgical Exposition in Durand's Rationale." Harvard Theological Review, 86, 1993, pp. 65-79.

See Viticulture

See Magic

Witigis (d. 542) was an Ostrogoth king of Italy. He was declared king by the nobility in opposition to the ineffectual Theodahad in 536 and immediately ordered Theodahad's death. Amid a circle of raised swords, Witigis was held aloft on a shield and hailed king—a ceremony that may have been Germanic in origin but had by then become essentially a Roman military tradition. He was also formally announced to the Goths by Cassiodorus in the language used to proclaim Roman emperors. Thereafter, Witigis's life was focused on warfare, but he did not abandon the other aspects of Ostrogothic government. He attempted to continue routine government in the areas under his control, and he minted coins in keeping with the issues of Theodoric. He promptly married Matasuentha, who was Athalaric's sister and Theodoric's sole surviving direct heir; the wedding was celebrated with a traditional Roman laudes given by Cassiodorus.

Initially, Witigis was fairly successful against the forces of Justinian I, but ultimately he had to withdraw all the Ostrogothic contingents from the borderlands to fight in Italy. The war soon centered on Rome, where Witigis and his forces were besieged. After many months, Witigis fled to Ravenna, where he and his wife were captured. However, Witigis went on to fight for Rome in the east until his death. His widow married Germanus, a nephew of Justinian.

See also Cassiodorus; Justinian I; Ostrogoths; Theodahad; Theodoric

THOMAS S. BURNS

Burns, Thomas S. The Ostrogoths: Kingship and Society. Wiesbaden: F. Steiner, 1980.

The rise of an export-oriented woolen industry in twelfth-century Italy can first be traced in the prosperous cities of the Po valley. The region was linked to the ports of Genoa and Venice by an efficient and low-cost system of river transport. It was also the southern terminus of the overland connections to the fairs of Champagne, which were a major conduit for the trade in fine Flemish cloth. The progression from rural coarse cloth production on monastic estates to an urban industry based on imitations of some grades of Flemish fabrics was a natural outcome of the growth of the ancillary crafts of dyeing and refinishing of Flemish cloth for reexport, which came to be concentrated in the Italian towns.

In the early stages of industrial development, urban producers drew on superior grades of domestic wool and imported merino wool from North Africa in order to create a line of uniform products which offered a low-cost alternative to Flemish woolens in Mediterranean markets. The spread of the new techniques from the towns of Lombardy and the Veneto (most notably Verona) to other cities in Tuscany and central Italy was effected through the organized migrations of textile workers under the sponsorship of host communes and local merchant entrepreneurs who offered numerous privileges and inducements to those willing to relocate.

The first decades of the fourteenth century witnessed a shift in marketing strategy as leading urban producers reduced their output of the middling and lower varieties of cloth in order to concentrate on higher-profit lines fabricated from imported English wools. This paralleled a similar shift in Flanders, which was a response to heightened competition from the spread of cloth manufacturing in various regions of Europe. It was also an attempt to meet a growing demand for fashionable luxuries among urban elites, a trend decried by contemporary moralist writers. As noted by the chronicler Giovanni Villani, the rapid rise of the Florentine woolen industry from relative obscurity to a position of prominence in the thirteenth century was due to the adoption of higher-margin luxury fabrics produced in limited quantities.

An exclusive reliance on English wool was undermined in the 1340s, when higher tariffs and reduced supplies forced a turn toward alternative sources of raw materials. Only a limited output of the finest luxury cloth based on English wool was maintained. Instead, prime grades of Spanish, Provencal, and Majorcan wools, improved through crossbreeding and systematic transhumance, were used in a second line of products, the launching of which entailed a substantial realignment of technical prescriptions. These included the application of cost-saving technologies such as the use of the spinning wheel for both warp and weft threads and the adoption of the fulling mill in place of labor-intensive fulling by foot. Experiments with dyestuffs and finishing techniques enhanced the surface characteristics of the fabric. Florence took the lead in the introduction of a fine, lightweight fabric woven from prime Mediterranean wools. Florentine garbo cloth, produced in a narrow range of qualities and prices, competed favorably with traditional Flemish and Brabantine fabrics in western Europe. It soon came to constitute the largest single category of Florentine woolen production and the standard that other industrial centers in Italy sought to reach.

Beginning in the 1350s, Florentine woolen artisans were actively recruited by other cities seeking to upgrade their industrial standards—an effort that accelerated after the ciompi revolt of 1378, in which woolen workers played a major role. Not all these attempts were successful. After 1400, a visible hierarchy based on specialization and product differentiation developed among textile centers. Leading cloth producers such as Florence, Verona, Bergamo, and Venice opened new markets for their brand-name fabrics among affluent urban consumers in the Ottoman empire and eastern Europe, where Italian woolens challenged and ultimately displaced Flemish luxury cloth. Spanish and other imported and domestic wools were used by towns and expanding industrial villages in Lombardy and the Veneto in the production of medium grades of cloth that also found outlets in Venetian trade. The position of Italian woolens in these external markets was not challenged until the end of the sixteenth century, when lower-priced English broadcloths and fine Dutch woolens made inroads into transcontinental and Mediterranean commerce.

The woolen industry was the most important industrial sector in medieval Italy in scale of production, level of capitalization, and size of the labor force, and it was a principal source of private and public wealth. Employers' guilds—a prime example of early capitalistic structures—coordinated the labor of thousands of wage earners, most of whom did piecework in their own homes. These guilds also controlled the dyers and finishers who managed their own workshops and employed apprentices and journeymen. An intense subdivision of labor developed, with specialized artisans in charge of each stage of production. Urban woolen guilds also claimed jurisdiction over rural weavers and spinners outside the city walls. Merchant entrepreneurs owned the tools, raw materials, and finished products and made all the decisions regarding investment and production. Loans extended to workers during slack seasons increased their dependence on employers. Infractions and debts of workers were adjudicated in the guild court, where fines and penalties were assessed.

In the 1370s, during a period of civil unrest and economic dislocation, tension within the industry led to citywide workers' revolts in Siena, Perugia, and Florence. Marxist historians have cited these revolts as evidence of an emerging proletarian consciousness; however, the demands of disenfranchised workers for recognition in guilds suggests a political strategy that was closely attuned to the prevalent ethos of urban corporate government. Still, over the long run violent uprisings among the laboring classes contributed to a weakening of communal institutions.

See also Ciompi; Florence; Fustians

MAUREEN FENNELL MAZZAOUI

Atti della prima Settimana di studio (18-24 aprile 1969): La lana come materia prima—I fenomeni della sua produzione e circolazione nei secoli X1II-XVII, ed. Marco Spallanzani. Florence: Olschki, 1974.

Atti della seconda Settimana di studio (10-16 aprile 1970): Produzione, commercio, e consumo dei panni di lana (nei secoli XII—XVIII), ed. Marco Spallanzani. Florence: Olschki, 1976.

Berti, Marcello. Lana, panni, e strumenti contabili nella Toscana bassomedievale e della prima età moderna. Lucca: Istituto Storico Lucchese, 2000.

Brucker, Gene A. "The Ciompi Revolution," In Florentine Studies: Politics and Society in Renaissance Florence, ed. Nicolai Rubinstein. London: Faber, 1968.

Doren, Alfred. Die Florentiner Wollentuchindustrie vom 14. Bis zum 16. Jahrbundert: Ein Beitrag zur Gescbichte des Modernen Kapitalismus. Studien aus der Florentiner Wirtschaftsgeschichte, 1. Stuttgart: J. G. Cotta'sche Buchhandlung, 1901.

Hoshino, Hidetoshi. L'arte delta lana in Firenze nel basso medioevo: Il commercio delta lana e il mercato dei panni fiorentini nei secoli XIII—XV. Florence: Olschki, 1980.

—. "The Rise of the Florentine Woollen Industry in the Fourteenth Century." In Cloth and Clothing in Medieval Europe: Essays in Memory of Professor E. M. Carus-Wilson, ed. N. B. Harte and K. G. Ponting. Pasold Studies in Textile History, 2. London: Heinemann Educational, 1983.

Mazzaoui, Maureen Fennell, "Artisan Migration and Technology in the Italian Textile Industry in the Late Middle Ages (1100-1500)." In Strutture familiari, epidemie, migrazioni nell'Italia medievale, ed. Rinaldo Comba, Gabriella Piccinni, and Giuliano Pinto. Nuove Ricerche di Storia, 2. Naples: Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane, 1984.

Rossini, Egidio, and Maureen Fenneil Mazzaoui. "Società e tecnica nel medioevo: La produzione dei panni di lana a Verona nei secoli XIII—XIV—XV." In Atti e Memorie delta Accademia di Agricoltura Seienze e Lettere di Verona, Series 6(1), 1969-1970.