Church of Sant' Andrea (Coilegiata), Empoli. Photograph courtesy of Christopher Kleinhenz.

Italy had educational structures and institutions different from those of the rest of medieval Europe. Although many of the same kinds of schools existed—monastery schools, cathedral schools, and later universities—their roles and institutional forms were often different from comparable institutions north of the Alps because of the more highly urbanized character of Italy, especially northern and central Italy. The most important difference was that Italy had Europe's only privately run schools with lay teachers before the eleventh century, and these non-church schools remained the norm until the sixteenth century. Some scholars have seen these urban schools as direct descendants of those run by grammarians and rhetoricians in the towns of the Roman empire. This continuity cannot in fact be demonstrated for any specific Italian city, but such schools are documented widely from the eleventh century onward and were remarked on, along with Italy's urbanized culture and high literacy rates, by contemporary travelers. Much of the burden of elementary education—reading and writing—seems to have been in the hands of private schoolmasters throughout the Middle Ages and into the Renaissance. These teachers could be women, both lay and religious, or part-time instructors such as priests, lawyers, and notaries who accepted individual students. Urban schools before the thirteenth century, however, were not usually organized by local governments, local churches, or monasteries but offered genuinely private tuition. The schoolmaster or schoolmistress contracted directly with parents to teach their children. Even when other, more formally organized schools existed, private tuition in small schools continued alongside them.

The reading and writing schools provided these fundamental skills to the citizens of increasingly commercial Italian cities and reflected the precocity of Italians in developing written records of all sorts. Another skill taught in medieval Italian schools was abaco. This word is related to English "abacus," but the course concerned far more than counting on the adding frame. Abaco was the subject we would call business arithmetic. It was taught exclusively to boys. In Tuscany, especially at Florence, there were separate abaco schools offering a full-time course; elsewhere, abaco was usually combined with the intermediate reading and writing course. At Genoa, for example, where Latin was used for business records far longer than in other cities, there was a combined course in business Latin and abaco, aimed at the sons of merchants.

Starting in the thirteenth century, city governments often subsidized private elementary schools or opened their own public schools. Usually the commune would contract to provide a house for the school, or would help the master find one, and pay him a fixed salary. The master in turn promised to reside continuously in the city and instruct all who came to learn. Sometimes masters were required to give poor students free lessons, but usually the master would collect fees over and above his salary for the various levels of instruction. Like the course itself, the fees were task-oriented rather than temporal. Students did not pay an annual tuition, but instead paid a set amount to learn the ABCs, another amount to master the primer, and so on, no matter how long these tasks took. The educational psychology implicit in such a system was that the students learned by imitation of the master, and that each task had to be mastered thoroughly before a student went on to the next one. This notion depended in turn on a Neoplatonic epistemology whereby the student's imitation was seen as a return to the "Creator," mediated by the teacher. Every task had a moral value over and above its specific content. Children were not thought to have a distinct psychology but were considered capable of making moral decisions and developing moral habits in the same way as adults. This approach explains why the communal contracts for grammar teachers almost always described their job as nurturing and safeguarding the morals of the city's youth.

Tbhere was no fixed age for starting school; most children who were sent out to reading schools started between ages seven and ten, but some began later while others, especially those tutored at home, might start to read at five or six. After learning to read and write, students had several options. For some, reading and writing were the only skills needed, and they would therefore go directly into the workplace. Others would take the abaco course, which could be combined with practice in keeping business records either in Latin or in the vernacular. A small number went on to study Latin in grammar schools, so called because in the Middle Ages Latin was the only language taught through the analytical rules called grammar. In medieval Italian usage, the word grammatica meant Latin. Grammar students learned Latin by memorizing the texts of the primer, usually prayers and psalms, followed by a simple grammar rule book, and then the moral proverbs of the Distichbs of Cato (Disticha Catonis) or the fables of Aesop. Intermediate reading texts included such patristic poets as Prosper of Aquitaine and Pr-u dentius, and also medieval school poetry that imitated Ovid. One common text of this sort was the Elegy of Arrigo da Settimelio. Most of the earliest texts given to schoolchildren were poetry, because poetry was believed to be more enjoyable for children and easier for them to memorize. Memory training was an essentil! part of education at every level. It equipped the student with a large body of easily quotable commonplaces for almost every theme or subject; and in accord with the prevailing Neoplatonic pedagogical theories, it was believed to give a structure to the mind itself that mirrored the ordered plan of the created world.

The Latin program of study is best attested to for the city-sponsored schools of the fourteenth century, but its elementary levels had been much the same in the earlier Middle Ages. There were regional variations in the texts used, and individual teachers had a great deal of freedom in choosing texts, but the techniques of teaching through imitation and memorization were constant. One important change that did occur in Italy from the late twelfth century onward was that students began to have an opportunity to learn to read in Italian only, without studying any Latin at all. In the earlier Middle Ages, Latin had been the only written language, and so learning to read meant learning to read Latin. But as city life grew more complex, commercial and even legal records began to be kept in local dialects; thus more and more people learned to read only the volgare, or vernacular.

However, Latin remained the language of the educated classes and a prerequisite for university education; therefore, students who had completed the elementary and intermediate Latin course would normally go on to study Latin for several more years before entering the university. This preparatory course was intended to give students facility in reading and writing Latin; it was called auctores ("authors") because it consisted of intensive study of the authoritative Latin poets and prose writers of the ancient world. The exact curriculum depended on the teachers' and students' interests, but it most often included Virgil, Horace, Ovid (often in expurgated or "moralized" versions), Seneca, and Boethius. As with the more elementary texts, students parsed these texts word by word and committed them to memory. At the preuniversity level they would also analyze the texts according to the rules of classical rhetoric, and they studied history, geography, and mythology by learning the meanings of proper names used by the poets. The skills learned in this way would be applied later in professional courses in law, medicine, notarial arts, and ars dictaminis, all taught in the universities.

We should not imagine that the private and communal schools were the only educational institutions in medieval Italy. In the earlier Middle Ages, monastic and cathedral schools like those of northern Europe were much more important than private schools. Several of the cathedral schools, indeed, were very famous in their day: Pavia, Verona, Cremona, and Modena had important schools of this sort at various periods from the ninth century to the eleventh. Several of the great figures of the eleventh-century monastic reform movement, moreover, were educated in monastic schools of northern Italy: Lanfranc and Anselm, successively priors of Bee in Normandy and archbishops of Canterbury, are only the most notable examples. The monasteries of Bobbio (in Lombardy), Nonantola (near Modena), Farfa (north of Rome), Monte Cassino (between Rome and Napies) and La Cava (south of Naples) all had famous schools which accepted lay boys as well as aspiring monks. One major task of schools attached to cathedrals and monasteries was teaching singing for liturgical purposes. Like grammar, music instruction relied heavily on memorization. Texts and melodies were learned together, and the pattern of each was used to reinforce the memorization of the other. The monastic reformers of the eleventh and twelfth centuries stressed the education of monks as a religious elite, and they discouraged "external" schools—i.e., schools for boys from outside the monastery. Gradually, Italian monasteries followed the example of French and German monasteries in withdrawing from the field of education. With the establishment of the mendicant orders in the thirteenth century, however, clerics took on a broad educational role again, first as preachers, then as educators of their own postulants at studia in the major Italian towns, and eventually by opening their schools to a limited number of lay auditors. It is believed that Dante attended lectures of this sort at Santa Maria Novella in Florence. For the most part, monasteries in later medieval Italy offered only upper-level courses and avoided elementary education.

Girls were excluded from the city-run schools and from most private schools beyond the level of reading and writing. They could, however, learn other skills if their parents would allow it, since additional schooling could be had in convents, or, for girls in wealthier families, from private tutors at home. Latin and arithmetic were only rarely taught to girls; instead, their usual education concentrated on domestic arts like cooking and sewing. Even the convent schools taught embroidery and other handwork that could be sold for income. Italian convents of the later thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, especially those associated with the mendicants, often had a very lively cultural life. The nuns read widely and sometimes wrote devotional texts and poetry themselves; they often copied or decorated manuscripts for their own use or for income; they taught their own postulants reading, writing, and sometimes Latin; they accepted lay girls for finishing courses; and they patronized artists, writers, and craftspeople beyond their walls. Much of the devotional literature in Italian composed in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries was intended for women.

In general, it is fair to say that Italian schools were the most varied and most practically-oriented in Europe before the fourteenth century. They reflected Italy's highly developed city life and also a businesslike approach to education, as to commerce, on the part of the Italian ruling classes. The schools at all levels, right up to the university course, stressed practical professional skills and deemphasized the study of speculative subjects like theology, philosophy, and even literature.

See also Arrigo da Settimello; Dante Alighieri; Disticha Catonis; Ovid; Ovid in the Middle Ages; Universities; Virgil; Virgil in the Middle Ages

Paul F. Gehl

Alessio, Gian Carlo. "Le istituzioni scholastiche e l'insegnamenco." In Aspetti della letteratura latina nel secolo XII, ed. Claudio Leonardi and Giovanni Orlandi. Florence and Perugia: La Nuova Italia, 1986, pp. 3-27.

Bolgar, R. R. The Classical Heritage and Its Beneficiaries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1954.

Davis, Charles T. "Education in the Time of Dante." Speculum, 40, 1965, pp. 415-435.

Frova, Carla. "Le scuole nella città tardomedievale." In La città in Italia e in Germania nel medioevo, ed. Reinhard Elze and Gina Fasoli. Annali dell'lstituto Storico Italo-Germanico, Quaderno 8. Bologna: II Mulino, 1981, pp. 119-143.

Gehl, Paul F. A Moral Art: Grammar, Society, and Culture in Trecento Florence. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1993.

Grendler, Paul F. Schooling in Renaissance Italy: Literacy and Learning 1300-1600. Baltimore, Md., and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989.

Kennedy, George A. Classical Rhetoric and Its Christian and Secular Tradition from Ancient to Modern Times. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1980.

Klapisch-Zuber, Christine. "Le chiavi fiorentine del Barbablu: L'apprendimento della lettura a Firenze nel XV secolo." Quaderni Storici, 19, 1984, 765-792.

Larner, John. Culture and Society in Italy 1290-1420. New York: Scribner, 1971.

Lenzi, Maria Ludovica. Donne e madonne: L'educazione femminile nel prima Rinascimento italiano. Turin: Loescher, 1982.

Manacorda, Giuseppe. Storia della Scuola in Italia. Milan: Remo Sandron, 1914.

Petti Balbi, Giovanna. L'insegnamento nella Liguria medievale: Scuole, maestri, libri. Genoa: Tilgher, 1979.

Le scuole degli ordini mendicanti (secoli XJII-XIV). Convegni del Centre di Studi sulla Spiritualita Medievale, 17. Todi: Accademia Tudertina, 1978.

Thorndike, Lynn. "Elementary and Secondary Education in the Middle Ages." Speculum, 15, 1940, pp. 400-408.

See Giles of Rome

The Embriaco were an old noble family of Genoa, originally viscounts, descended from a branch of the Ghibelline Spinola clan. The Embriaco played a major role in the process whereby the Genoese nobility conquered eastern trade routes and built a commercial empire in the Mediterranean during the eleventh and twelfth centuries—a process that the historian Henri Pirenne and Lopez (1938, 1976) described as the early "crusading-military-mercantile privatism" of these nobles. It established Genoa, along with Pisa and Venice, as a leading trading center in the Mediterranean and European economies, driven by the wealth of Muslim, Chinese, and southeast Asian silk and spice routes.

The rise of the Embriaco in the early Genoese republic was due to Guglielmo, a military leader of the First Crusade (1097-1104). Guglielmo commanded the large Genoese fleets—de-scribed in the Annali of the chronicler Caffaro (who was himself a member of the expedition of 1099)—that took the ports of San Simeon, Arsuf, and Caesarea, opening Genoese trading colonies in Antioch and other markets in the Holy Land. According to Caffaro, Guglielmo scuttled one fleet and used the wooden ships to make inventive siege weapons; as a result, Jerusalem fell to the Christian crusaders on 15 July 1099. Guglielmo's tenacity as a fighter earned him the nickname Testadimaglio, or "Mallethead." He was an ally of Baldwin I, who became king of Jerusalem. As the Genoese consul exercitus Ianuensium (commander of the army) he celebrated with Baldwin the ceremonial liberation of the Holy Sepulchre with a miraculous paschal "mass of lights" and baptismal ablution in the Jordan River.

With the First Crusade, spoliation of eastern relics became an integral part of western colonization. The relics of Saint John the Baptist were brought to Genoa from Mira and installed in the cathedral of San Lorenzo; thus John became Genoa's patron saint and its ceremonial focus. Guglielmo was personally responsible for the furta sacra ("sacred theft") of the Sacro Catino from Caesarea; this is a plate or basin of green glass and emerald work from late antiquity with a relief of the head of Christ (or John the Baptist) in the center. According to one legend, it was the plate on which Christ instituted the eucharist at the Last Supper; according to other legends, it was the plate on which the severed head of John the Baptist had been presented to Herod. Today it is in the treasury of San Lorenzo, where it is still revered by worshipers. Such relics, with their ties to the Holy Land, helped define the religious and communal life, the "sacred landscape," of Genoa—as of other early European republics and kingdoms—along with the private associations (compagna communis) that made the Genoese crusades possible.

As a result of the conquests and spoils of the First Crusade, the Embriaco gained a monopoly on trade to Antioch and Syria, the source of their wealth and power. The family also became established as lords of Gibelet (Jubail in Arabic) in the strategic coastal city and county of Tripoli, where they remained for two centuries until they disappeared, with the last of the crusader states in the Holy Land, in the late 1290s. The triumphal return of the Genoese fleet in 1101, immortalized by Caffaro, celebrated Guglielmo's military prestige; and Guglielmo's election as consul of the republic in 1102, with his father, Guido Spinola, and a relative, Ido di Carmandino, put him in virtual control of the city.

The twelfth-century fortress tower of the Embriaco near Santa Maria di Castello, with its impressive height and its hillside situation overlooking the medieval city and harbor, is a symbol of the family's almost seigniorial power during the early republic. It is also an early example of medieval rustication, with crenellated battlements crowning the top (although it was heavily restored in 1923). The Embriaco fell into extinction during the thirteenth century, but their proud tower still remains.

See also Crusades; Genoa; Spinola Family

GEORGE L. GORSE

Annali genovesi di Caffaro e de' suoi continuatori dal MXCIX al MCCLXXXXVII, 14 vols., ed. L. Belgrano. Genoa, 1890-1929, Vols. 1—2.

Cancellieri, J.-A. In Dizionario biografico degli italiani, Vol. 42. Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 1993, pp. 574-582. (Articles on the Embriaco family.)

Epstein, Steven. Genoa and the Genoese, 958-1528. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

Geary, Patrick J. Furta Sacra: Thefts of Relics in the Central Middle Ages. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1990.

Lopez, Robert S. Storia delle colonie genovesi nel Mediterraneo. Bologna: Zanichelli, 1938.

—. The Commercial Revolution of the Middle Ages, 950—1350. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976.

Runciman, Steven. A History of the Crusades, 3 vols. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1951-1954.

See Byzantine Empire

See Holy Roman Empire

Empoli is situated in the agriculturally rich lower Arno valley, about 17 miles (28 kilometers) from Florence and 4 miles (7 kilometers) from the confluence of the Arno and Elsa rivers. In the Middle Ages the important Via Francigena, the main road from Rome to France, crossed the Arno near the castle, and later the town, of Empoli. The town was thus at a junction of the land route northward to France and southward to Siena and Rome with the water route by the Arno from Florence to Pisa and the sea. The name Empoli is ancient; it apparently derives from "emporium," and from the early twelfth century on Empoli has indeed been an important commercial center. Its moment of fame came in 1260, when the Ghibelline victors of Montaperti met there to decide the fate of Guelf Tuscany.

Ancient Roman remains were discovered in 1984, and a document of 780 mentions a church of San Michele "in Empoli." Until 1015, the area around the castle was controlled by Pisa— in fact, it was on the border between Florentine and Pisan territories. In that year the populace revolted and scattered, and Pisans destroyed the castle. The territory fell under the lordship of the Guidi counts, and the local pieve, or regional baptismal church, of Sant' Andrea served as a locus for a new market village. In 1119, the countess Emilia, wife of Count Guido Guerra, established this church (today, collegiata) as the center for fourteen regional churches and chapels, and their incomes. From this time on the town grew quickly. The people of Empoli generally controlled their own civic affairs, and they formed a defensive alliance with the nearby villages of Monterappoli and Pontorme.

With the descent of Emperor Frederick Barbarossa into Italy, Empoli submitted itself to the protection of Florence in 1181 — 1182.he emperor imposed his own vicar in 1184, but four years later Florence regained control. In 1255, Florence bought out the Ghibelline Guidi counts and installed its own podesta. In 1260, after their victory at Montaperti, Ghibelline leaders, including some of the Guidi, pressed for the razing of Florence. The Florentine exile Farinata degli Uberti argued successfully against this, and the city was spared. After the tables turned, the central position of Empoli made it a natural meeting place for Guelf leaders from Tuscany in 1295, 1297, and 1304, and in 1312, when Tuscan and Bolognese Guelfs convened to discuss their strategy against Emperor Henry VII.

Empoli suffered during the wars between Castruccio Castracane and Florence in 1315-1328, and later during Florence's battles for control of Pisa. In 1333, a terrible flood of the Arno badly damaged the town, and its walls, some sections of which dated from the eleventh century, were ruined. They were completely rebuilt in 1336, however, and were provided with towers and two main gates. These walls were famous in their day, but only a portion of them, dating from 1487, still exists.

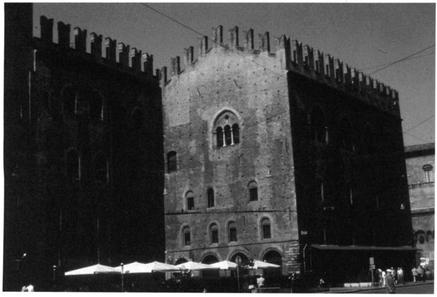

Church of Sant' Andrea (Coilegiata), Empoli. Photograph courtesy of Christopher Kleinhenz.

The pieve of Sant' Andrea was rebuilt beginning in 1093, and its geometric twelfth-century facade in white and dark-green stone is reminiscent of San Miniato al Monte in Florence. The interior of Sant' Andrea was remodeled in the eighteenth century, but it retains a few works from the fourteenth. The Augustinian church of Santo Stefano (1367) has never had a formal facade; however, it contains important remnants of frescoes by Masolino (1430s).

See also Farinata degli Uberti; Florence; Henry VII of Luxembourg; Montaperti, Battle of

JOSEPH P. BYRNE

Fonti e studi di storia empolese. Empoli: Comune di Empoli, 1980

Galletti, G. La collegiata di Sant'Andrea a Empoli. Fucecchio: Edizioni dell'Erba, 1991.

Lastraioli, Giuliano. "Empoli fra feudo e comune." Bollettino Storico Empolese, 4, 1960, pp. 83-104.

Lazzeri, Luigi. Storia di Empoli. Empoli: Tipografia Monti, 1873. (Reprint, Bologna: Atesa Editrice, 1988.)

Enna is a hilltop town in central Sicily. It was known as Enna in classical antiquity but was renamed Kasr Janni under the Muslims; this Muslim name was the derivation of its medieval name, Castrogiovanni, which was retained until 1927.

Enna is important particularly for its role in the Norman conquest of Sicily during the eleventh century. Its mountainous setting and well-fortified castle, parts of which remain today, made it virtually impregnable. The Muslims captured Enna, in the ninth century, only by worming their way under the walls through the sewers. Around 1060, it was the seat of the emir Ibn al-Hawas, one of three major figures in the confused politics of Sicily—an island whose rulers were oblivious of the Norman threat and were preoccupied with establishing their independence from one another and from the the Zirid of Tunisia. In 1060-1061, Ibn al-Hawas held his own sister captive in Enna; she was married to the powerful ruler of Catania (on the eastern coast of Sicily), Ibn al-Thimnah, who tried to win her back by force but was repulsed. In desperation, Ibn al-Thimnah went to Mileto in Calabria and begged the Normans for aid against his enemies. Roger I, brother of the most successful Norman warlord in southern Italy, joined forces with the emir of Catania, first overwhelming Messina and then marching on Enna. In the fields outside the town, the Normans scored a notable victory over a numerically superior enemy, but they were not able to storm the stronghold of Enna.

The Normans' presence in Sicily eventually united most of the Muslims against them, although in 1067 Ibn al-Hawas was killed in a battle against the Zirid, who had come to save Sicily from being conquered by Christians. Enna itself continued to hold out remarkably well against the Normans, and it was one of the very last places to submit to Roger I (the last was Noto, in 1090). The end came for Enna in 1086, when Roger I captured the children of the new emir of Enna, Ibn Hammud, at Girgenti (Agrigento). Roger began to negotiate with Ibn Hammud, who decided in 1087 to abandon Enna to the Christians. Hammud marched out of the town; allowed his procession to be surrounded by the Normans, to whom he could then honorably surrender; accepted baptism; and went to live on lands granted to him in Calabria.

During the late twelfth century, there were still descendants of Muslim converts to Christianity in Enna, although the town stood in an area that was being subjected to intensive colonization by Christian settlers from the Italian mainland, the so-called Lombardi. One such Christianized Arab may be Maymun of Castrogiovanni, who is recorded as making a donation to a monastery at Caltanissetta in 1179.

Something is known of the economic role of Enna in the late Middle Ages. There were craft guilds in the town by the mid-fifteenth century. References to fairs begin not later than 1420. Between 1277 and 1478, the number of hearths in the town decreased, as elsewhere in Sicily; but at those two extremes there seem to have been some 2,000 hearths, which would indicate a population of approximately 10,000. The saltworks of Enna are mentioned repeatedly in fifteenth-century charters. Its rock salt, needed in the making of cheese (a great Sicilian specialty), was exported to Catania. In 1459, work was under way to exploit new alum mines in the region of Castrogiovanni. In 1453, Alfonso V granted Pietro Mozzicato of Enna the right to explore for alum throughout Sicily. On the other hand, social tension developed in Enna. In 1453, the city seems to have been divided among four factions, gentilhomini, menestrali, borgesi, and the popolo. In 1463-1464 royal taxation was a particular source of tension. In this respect Enna shared the outlook of the other medium-sized Sicilian towns.

See also Arabs in Italy; Roger I; Sicily

DAVID ABULAFIA

Amatus of Monte Cassino. Ystoire de li Normant, ed. Vincenzo de Bartholomaeis. Rome: Fonti per la Storia d'ltalia, 1935.

Bresc, Henri. Politique et société en Sicile, XII-XV siècles. Aldershot: Variorum, 1990.

Epstein, Stephan R. An Island for Itself: Economic Development and Social Change in Late Medieval Sicily. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Maiaterra, Gioffredo. De rebus gestis Rogerii Calabriae et Siciliae Comitis et Roberti Guiscardi ducis fratris eius, ed. Ernesto Pontieri. Rerum Italicarum Scriptores: Raccolta degii Storici Italiani dal Cinquecento al Millecinquecento, 5, Part 1. Bologna: Zanichelli, 1928.

Norwich, John Julius. The Other Conquest. New York: Harper and Row, 1967.

Enzo (Enzio, c. 1220-1272) was the natural son of Emperor Frederick II Hohenstaufen and an unknown mother. His name was Heinrich, but in Italy he was called Enzo or Enzio. He was the favorite of his father, of whom he was said to be the very image. Sources portray him as handsome, cheerful, fearless, and poetic. Enzo played a substantial role in imperial politics from 1238 until his capture in battle in 1249.

In 1238, Enzo married Adelasia, the widowed ruler of Torres and Gallura in northern Sardinia. Enzo never ruled Sardinia— he came there just long enough to marry Adelasia and to appoint vicars—but the emperor proclaimed him king of Sardinia, and Enzo continued to use that title even after his marriage to Adelasia was annulled in 1245. In July 1239, Frederick appointed Enzo "legate general of all Italy," a "living image" of the emperor to preside over the imperial vicars general of cities in central and northern Italy. Enzo was also empowered to arbitrate disputes, hear appeals, and appoint notaries and judges. Most significantly, he commanded imperial troops and collaborated with Ghibelline warlords such as Ezzelino III da Romano to fight Guelf forces in Tuscany, Lombardy, and the Romagna.

Palazzo di Re Enzo (where Enzo was imprisoned), Bologna. Photograph courtesy of Christopher Kleinhenz.

Enzo was one target of a foiled conspiracy against Frederick in 1246, in which many of the emperor's closest friends and advisers were implicated. In the reorganization of the imperial government that followed, Enzo was assigned to Lombardy and the Romagna. He campaigned continuously against the Guelfs in the region. In May 1247, while Enzo was besieging a fortress near Brescia, a Guelf force stole into the city of Parma and seized it. The protracted and mishandled siege that ensued was a disaster for Frederick. In 1248, Enzo married Ezzelino's niece. Enzo was captured at Fossalto in a skirmish against Guelfs from Bologna in Januaiy 1249. Frederick tried desperately to persuade the Bolognese to release him, but they refused. The capture of Enzo crippled imperial policy in Lombardy.

Enzo was imprisoned comfortably in Bologna for the rest of his life. There he wrote simple but affecting poems and songs, many of which are extant. He corresponded widely and was free to receive visitors, both male and female. However, the execution of his nephew, Conradin, by Charles of Anjou in 1268 awakened in Enzo a desire to resurrect the Hohenstaufen cause in Italy. In 1270, he attempted to escape, but he was recaptured and was thereafter held in close confinement until his death in 1272. The commune of Bologna gave Enzo a royal funeral and, at his request, buried him in the church of San Domenico.

See also Bologna; Ezzelino III da Romano; Frederick II Hohenstaufen; Hohenstaufen Dynasty; Scuola Poetica Siciliana

JOHN LOMAX

Historia diplomatica Friderici Secundi, 6 vols, (in 12), comp. J.-L.-A. Huillard-Bréholles. Paris: H. Plon, 1852-1861.

Legum sectio IV: Constitutiones et acta publica imperatorum et regum, 2, ed. Ludwig Weiiand. Monumenta Germanise Historica. Hannover: Halin, 1896.

Riera, Clelia. I poeti siciliani di casa reale (re Giovanni, Federico II, re Enzo): Testo critico. Palermo: Tipografia Stella, 1934.

Salimbene de Adam. The Chronicle of Salimbene de Adam, trans. J. L. Baird et al. Binghamton, N.Y.: Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies, 1986.

—. Cronica, 2 vols., ed. Giuseppe Scalia. Corpus Christianorum: Continuatio Mediaevalis, 125. Turnholt: Brepols, 1998-1999.

Blasius, Hermann. Konig Enzio: Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte Kaiser Friedrichs II, Breslau: W. Koebner, 1884.

Kantorowicz, Ernst. Frederick II, 1194-1250, trans. E. O. Lorimer. New York: Frederick Ungar, 1931.

Morghen, Raffaello, II tramonto delta potenza Sveva in Italia. Rome: Tunninelli, 1936. (Reprint, L'età degli svevi in Italia. Palermo: Palumbo, 1974.)

Munch, Ernst Hermann Joseph. Konig Enzio: Aus den Quellen neu bearbeitet mit Beilagen. Stuttgart: J. F. Cast'schen, 1841.

Erice, a hilltop community in western Siciliy, was known in the Middle Ages as Monte San Giuliano (Mount Saint Julian), a name it kept until Mussolini restored its ancient name, Erice, in 1936. It occupies one of the oldest inhabited sites on the island; its castle stands on the site of a shrine that predates the Greeks. The town is 750 meters (nearly 2,500 feet) above sea level and has its own microclimate; often, Erice is enveloped in clouds while the neighboring port of Trapani, a mere 6 kilometers (less than 4 miles) away, basks in sunshine. But Trapani has an unhealthy setting, amid marshes, and this may have led settlers to choose the cooler climate of Erice. On a clear day, Africa is visible from Erice to those with sharp eyes.

Our knowledge of the town c. 1300 is especially detailed, because the notarial register of Giovanni Maiorana from this period, preserved in the state archives in Trapani, is rich in information about the life of Erice's Christians and Jews. The town still retains many medieval monuments, notably the cathedral (the duomo) and other churches, as well as a Norman castle. Its Franciscan and Dominican convents have become the base of a conference center (Centro Ettore Majorana) where regular study weeks devoted to medieval civilization are held.

The history of Monte San Giuliano begins afresh with the Norman conquest of Muslim Sicily. In 1077, Roger I, count of Sicily, besieged the hill town then called Jabal Hamid; the story is that he succeeded in capturing it only because he was helped by a pack of dogs led by Saint Julian, whose name was thereupon given to the settlement. In the twelfth century, the Granadan traveler Ibn Jubayr reported that the women of Erice were the most beautiful on the island. By then, the Muslims had been expelled from Erice, and Jubayr reports that for reasons of defense, the Christians would not allow any Muslims to set foot on the mountain; the Christians' view was that if Erice fell, the entire island would fall.

In the thirteenth century, Erice was providing Trapani with basic necessities and became a significant center of immigration. The population of Erice had originated in Amalfi, Salerno, Naples, Apulia, Calabria, northern Italy, and even Catalonia; it also still included a significant Jewish group, who continued to speak Arabic and had their own universitas, or community organization, parallel to the universitas of the Christians. The Jews accounted for about 5 or 6 percent of the population as a whole, which was estimated at approximately 7,000 c. 1300, and were particularly involved in winemaking on the slopes of the mountain. Jews and Christians lived mixed together, although in the late fourteenth century a separate giudecca (ghetto) seems to have evolved; this giudecca was the scene of brutal forced conversions in 1392. The town appears by then to have been experiencing serious economic difficulties, and an appeal to King Martin I in 1407 emphasized the abandonment of properties by refugees from violence during the power struggles of the "four vicars" at the end of the fourteenth century. Without doubt, this depopulation was accentuated by pestilence from 1347 onward (though it is known that there were still 838 hearths in 1374). Generally, the town was renowned for its loyalty to the house of Barcelona after the Aragonese invasion of 1282.

See also Normans; Sicily; Trapani

DAVID ABULAFIA

Abulaha, David. Commerce and Conquest in the Mediterranean, 1100-1500. Aldershot and Brookfield, Vt.: Variorum, 1993. (See Chapter 8, "Una comunita ebraica della Sicilia occidentale: Erice 1298-1304," reprinted from Archivio Storico per la Sicilia Orientale, 80, 1984, pp. 157-190.)

Adragna, Vincenzo. Erice. Trapani: Coppola Editore, 1986.

De Stelano, Antonio. II registro notarile di Giovanni Maiorana (1297-1300). Palermo: Istituto di Storia Patria per la Sicilia, 1943.

Sparti, Aldo. II registro del notaio ericino Giovanni Maiorana (1297-1300), 2 vols. Palermo: Accademia di Scienze Lettere e Arti, 1982.

Mount Etna, with an altitude of some 3,350 meters (10,990 feet), is the highest elevation in Sicily and the largest active volcano in Europe. It is a massif with subsidiary peaks, and on a clear day it can be seen easily from Calabria across the Strait of Messina. Its roughly oval base is about 212 kilometers (132 miles) around and covers an area of some 1,250 square kilometers (483 square miles). It is bounded on the east by a narrow coastal plain, on the north and west by the rivers Alcantara and Simeto, and on the south by the plain of Catania. Etna was famous in ancient literature as a spectacular instance of vulcanism; during the Middle Ages it was a topographical feature on and around which humans moved, a threat to inhabitants of the region, an object of scientific inquiry, and a place of supernatural and mythological significance.

Medieval Etna had several names. The traditional Greek Aitne and Latin Aetna or Etna were standard in the early Middle Ages and remained customary in learned writing throughout the period. Arabs called it Gebel (or, in a transliteration more closely approximating western Mediterranean pronunciations, Djebel) el-Nar, "mountain of fire"; the geographer al-Idrisi, writing under Roger II in the early 1150s, used this name for Vesuvius as well. From this name, or from an abbreviation, came the Latin names Gibellus and Gyber and the Italian Mongibello, whose first element also signifies a mountain; hence, too, the Latin analogue of Mongibello, Muntgibel, and the Greek Moukipelo. Although its adjacent plains had long been cultivated, and although there was a road system around it with towns of varying age at strategic points, the mountain itself was thickly wooded and thinly populated. The residents we know most about were monks and hermits, but brigands and others also found refuge here.

As early as the year 604, there was a monastery of Saint Vitus on Etna; the alleged improprieties of its inhabitants are the subject of two letters by Gregory the Great. The ruins of the "Cuba" of Santa Domenica near Castiglione di Sicilia and lesser remains elsewhere in the Alcantara valley indicate extensive monasticism in the vicinity during the period when it was under the rule of eastern Rome (Byzantium). In the wake of the Norman conquest, settlement by the island's Greek minority expanded in this region, and by the early twelfth century Etna's slopes were dotted with hermitages and with monastic foundations practicing the Greek rite. Among these were the little church of Santa Maria di Maniace, established before 1105 to commemorate a victory by the eastern Roman general George Maniakes over Arab forces on Etna's northwest shoulder c. 1040; the monastery of San Nicola di Pellera near Randazzo, attested to by a donation of the countess Adelaide (regent, 1101—1115); and the monastery near the cave in which Joachim of Fiore lived briefly after his return from the Holy Land in the late 1160s.

In time, these sites were either abandoned or taken over by the Latin church, which also created new ones. Santa Maria di Maniace, refounded in 1173 as a Benedictine abbey by the queen mother, Margaret of Navarre, is a striking example of Norman architecture. Many sites on the eastern and southern sides of Etna were said to have been destroyed by a violent eruption in 1329, but later foundations continued the tradition. One on the south side was the Benedictine abbey of San Nicola 1'Arena, which was expanded from a Norman grange of the same name by Frederick III (1296-1337) and was famous as the final residence of his queen, Eleanor of Anjou (d. 1341). On the east slope near Milo, in the town forest of Mascali, was the chapel founded by John of Aragon (regent of Sicily, 1340-1348); John had a summer retreat next to this chapel, and he withdrew here in an unsuccessful attempt to avoid the black death. As the practice of designated forests (which included open areas) suggests, Etna's flanks were used, at least during the central and later Middle Ages, for woodcutting and for herding; locally felled timber supported shipbuilding at the arsenals in Mascali and Messina. The mountain also furnished foodstuffs: fungi, acorns, chestnuts, and—since its fauna was richer then than today—wild game. Ecclesiastical sites had territories of their own, often with associated villages: those of San Nicola l'Arena and, on the east side, the fourteenth-century priory of San Giacomo became today's Nicolosi and Zafferana Etnea.

How often Etna erupted during the Middle Ages is not known. Many eruptions are listed, but only those in 1329, 1333, 1381, and 1408—i.e., from later centuries when our sources are better—are historically verifiable. The thirteenth-century Prophecy of the Erythrean Sibyl, parts of which are thought to be older and of Sicilian provenance, predicts that the end of the world will be heralded by a burning river coming from Etna; this prediction could have been based on an actual event, but again proof is lacking. The famous earthquake that leveled Catania in 1169 is now thought not to have originated in Etna. Etna is said to have shaken violently in 1285, after the death of Charles I. Arab sources indicate eruptions in the tenth and eleventh centuries. There may also have been events during the earlier medieval period. Versions of the legend of Saint Agatha, whose lost original (possibly sixth century) reflected perceptions current in its own time, recount how the citizens of Catania displayed the funeral veil of their new saint (supposedly in the year 252) and so protected the city from the advancing fires of Etna. The eighth-century Anglo-Saxon nun Huneberc of Heidenheim, narrating a pilgrimage to the Holy Land made by her contemporary Saint Willibald, reports that the custom then was to display the martyr's body; this, she says, will stop the flames immediately. In 1329, Agatha's relics were produced for this purpose— successfully, although the plain of Catania and much of the coast were devastated. Much the same happened in 1381, when a large lava flow ran right along the northern edge of the city.

There was very little scientific inquiry into volcanic phenomena during the Middle Ages, a time when nature was understood predominantly in terms of theology or of physical explanations that had been inherited, with few changes, from antiquity. In his Encomium of Saint Agatha (possibly c, 845) the Sicilian-born patriarch Methodius I quotes the patristic writer Gregory of Nazianzus to establish Etna's flowing lava as a marvel: its combination of characteristics associated with the contrary elements fire and water revealed Christ's unbounded power. In a long poem to Adela of Blois (after 1102), Baudri of Bourgeuil lists Etna, in flames, among a number of divinely ordained natural wonders. Yet the lengthy praise of Sicily in the late eleventh-century Life of Saint Philaretus the Younger refers to the origin of Etna's fire and the manner of its eruptions purely as an unsolved scientific problem. This may have been merely rhetorical ornamentation in an ancient mode; but in Baghdad in the early twelfth century the learned Sicilian exile Abu al-Qasim ibn al-Hakim provided details of Etna in eruption, some fabulous but others taken from actual observation (although not necessarily recent or his own). In the 1150s, Henry Aristippus, a Catanian cleric who was a figure at the Sicilian court, studied Etna's activity at close range; he also translated the part of Aristotle's Meteorology dealing with the liquefying and congealing of matter. Ristoro d'Arezzo's late thirteenth-century encyclopedia The Composition of the World, in its treatment of vulcanism, gives measurements of the length and breadth of one of Mongibello's lava flows.

The ancients, however, had explained volcanoes not only by reasoning from observation and analogy but also by myths of deities and their attendants at subterranean forges and of rebellious giants defeated in battle by the gods and punished by being imprisoned under fiery mountains. Ancient literary descriptions of Etna reflecting such polytheistic beliefs survived as models of style; and pagan concepts of a fiery underworld that could be entered through volcanoes or other sulphurous regions facilitated a medieval understanding of these places as portals to and from hell. Thus the very influential Isidore of Seville specifically identifies Etna as the biblical Gehenna; and the ninth-century Greek Life of Leo, Bishop of Catania, developing a theme from ancient Christian apologetics, observes of the ancient Greek philosopher Empedocles that the gods with whom he wished to speak when he insanely threw himself into Etna were really evil spirits. Thus, too, the Sicilian historian Nicola Speciale, whose partly eyewitness account of the eruption in 1329 bears comparison in some respects with Pliny the Younger's better-known account of Vesuvius in 79, records that after the event demons appeared on the mountain's slopes, assuming various forms and preaching frightful lies.

In the later Middle Ages, as Purgatory assumed an identity of its own in Christian belief, some people located it in Etna. But not all: when Caesarius of Heisterbach, a thirteenth-century writer of moral tales, has the now departed Duke Bertold V of Zaehringen (the rector of Burgundy and a former imperial candidate) sent to Mount Gyber, he specifies that this is hell and not Purgatory. When Caesarius lists volcanic mouths of hell in this tale (his third is Vulcano in the Eolian Islands, famous since Gregory the Great as a place of torment for the damned), he distinguishes Gyber from Etna; thus Etna's dual nomenclature could have given it added prominence among symbolic mountains of the medieval European world. There is a story associating Etna with both Purgatory and Hell in Anonimo Fiorentino's late fourteenth-century commentary on Dante's Divine Comedy. At Purgatorio 3.115, where the subject is Constance, the daughter of Manfred, Constance is said to have visited a holy hermit living on a mountain near Mongibello (the location is significant) and to have asked him to inquire of God whether her father, who had been an enemy of the church, were indeed damned; the hermit did so and then announced God's revelation that Manfred was among the elect in Purgatory.

If Etna was a place of the afterlife, then it could also be the ongoing residence of famous people who had disappeared from mortal sight. In the early thirteenth century, Gervase of Tilbury, an Englishman with experience in Sicily under William II, told a story centering on King Arthur, recently seen living perpetually in a palace on Muntgibel and suffering from a wound that never healed. Gervase's tale is evidently related to the legend of Arthur in Avalon and is probably connected with other Arthurian events and legends from the same general area (Richard I's presentation of Excalibur to King Tancred in 1191; the naming of the veil of mist in the Strait of Messina after Morgan le Fay, in Italian la Fata Morgana). This tale also had an Italian offshoot, a Tuscan poem of the Gatto Lupesco. Versions from elsewhere in Europe added clearly diabolical and punitive elements; other late medieval fiction explicitly located Morgan too at Etna. In different fashions, the idea was soon adapted for Frederick II, who had just died—both by his enemies and by those for whom his image was more positive. In 1258, Franciscan Joachites who saw Frederick as the Antichrist developed a fable in which he rode toward Etna with 5,000 horsemen in hellish armor. In 1261, the first of several false Fredericks, a ne'er-do-well from the territory of Adrano, took up residence on nearby Etna in furtherance of his claim. Only later did Germans place their Italian-born emperor in Thuringia's Kyffhaeuser mountains.

See also Arthurian Material in Italy; Frederick II Hohenstaufen; Sicily

JOHN B. DILLON

Agnello, Giuseppe M. "Terremoti ed eruzioni vulcaniche nella Sicilia medievale." Quademi Medievali, 34, 1992, pp. 73-111.

Amari, Michele. Storia dei Musulmani di Sicilia, 2d ed., rev. and enlarged, 3 vols. Catania: Romeo Prampolini, 1933-1939. (See especially Vol. 2, pp. 502-508.)

Backman, Clifford R. The Decline and Fall of Medieval Sicily: Politics, Religion, and Economy in the Reign of Frederick III, 1296-1337. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995. (See especially pp. 13-15, 74-77.)

Corrao, Pietro. "Boschi e legno." In Uomo e ambiente nel Mezzogiamo normanno-svevo: Atti delle ottave giornate normanno-sveve, Bari, 20-23 ottobre 1987, ed. Giosue Musca. Bari: Dedalo, 1989, pp. 135-164.

Graf, Arturo. "Artù nell'Etna." In Miti, leggende, e superstizioni del Medio Evo, Vol. 2. Turin: Ermanno Loescher, 1893, pp. 303-335.

Le Goff, Jacques. The Birth of Purgatory. Trans. Arthur Goldhammer. Chicago: 111. University of Chicago Press, 1984; esp. pp. 201-208, 401-402.

Lerner, Robert E. "Frederick II, Alive, Aloft, and Allayed, in Franciscan-Joachite Eschatology." In The Use and Abuse of Eschatology in the Middle Ages, ed. Werner Verbeke, Daniel Verhelst, and Andries Welkenhuysen. Mediaevalia Lovaniensia, Series 1(15). Louvain: Leuven University Press, 1988, pp. 359-384.

Pioletti, Antonio, "Artù, Avallon, l'Etna," Quademi Medievali, 28, 1989, pp. 6-35.

White, Lynn Townsend, Jr. Latin Monasticism in Norman Sicily. Academy Monographs, 13. Cambridge, Mass.: Mediaeval Academy of America, 1938. (See especially pp. 116-122, 145-148.)

Eudocia was the elder daughter of the emperor Valentinian III (r. 425-455) and his wife Licinia Eudoxia. She was betrothed to Huneric, the son of the Vandal king Gaiseric (Genseric, r. 428-477), apparently in the early 440s. In spite of this, after Valentinian was murdered in 455 she was married to Palladius, the son of the short-lived emperor Petronius Maximus. When the Vandals sacked Rome in the same year, she was carried off to Carthage along with her mother and her sister, Placidia, There, the marriage to Huneric was consummated. She became the mother of the later Vandal king Hilderic (r. 523-530).

See also Eudoxia; Gaiseric the Vandal; Valentinian III

RALPH MATHISEN

Clover, Frank M, "The Family and Early Career of Anicius Olybrius." Historia, 27, 1978, pp. 169—196.

De Salis, J. F. W. "The Coins of the Two Eudoxias, Eudocia, Placidia, and Honoria, and of Theodosius II, Marcian, and Leo I, Struck in Italy." Numismatic Chronicle, 7, 1867, pp. 203-215.

Licinia Eudoxia (b. 422) was the daughter or the eastern emperor Theodosius II (408-450) and Aelia Eudoxia. In 424 she was betrothed to the western emperor Valentinian III (r. 425-455), and the marriage was performed in Constantinople in 437. She bore two children, Eudocia and Placidia. She received the title augusta ("empress") in 439. In 455, after Valentinian was murdered in Rome, she was compelled to marry his successor Petronius Maximus; later, it was said that she invited the Vandal Gaiseric (Genseric) to Rome in the same year. After the ensuing sack, she and her two daughters were carried back to Carthage. Not until the early 460s were she and Placidia set free; they withdrew to Constantinople, where Eudoxia spent the remainder of her years. Eudocia remained in Africa as the wife of Gaiseric's son Huneric.

See also Eudocia; Gaiseric the Vandal; Valentinian III

RALPH MATHISEN

Clover, Frank M. "The Family and Early Career of Anicius Olybrius." Historia, 27, 1978, pp. 169-196.

De Salis, J. F. W. "The Coins of the Two Eudoxias, Eudocia, Placidia, and Honoria, and of Theodosius II, Marcian, and Leo I, Struck in Italy." Numismatic Chronicle, 7, 1867, 203-215.

Duckett, Eleanor Shipley. Medieval Portraits from the East and West. Ann Arbor, Mich., 1972.

Eugenius or Eugene III (Bernardo Paganelli, Bernard of Pisa; d. 8 July 1153) was the first Cistercian pope. He intially became vicedominus of the Pisan church (administrator of church possessions). After meeting Bernard of Clairvaux in 1135, he became a Cistercian monk at Clairvaux. By 1142, he returned to Italy as the abbot of Tre Fontane. He was appointed to the College of Cardinals, and he was elected to the papacy on 15 February 1145.

Eugenius was a crusading pope. He initiated and organized the Second Crusade (1148) with expeditions to the Christian east, Spain, and Germany. Exiled for much of his reign by the antipapal Roman commune, he also led campaigns for the recapture of Rome and other lands for the patrimony of Saint Peter. These campaigns, aided by Norman Sicily, secured the defeat of the commune, establishing the pope's temporal authority over his episcopal city.

Although not a canonist, Eugenius was in many regards the first lawyer-pope. He spent hours hearing and trying cases at the papal court, issued an unprecedented number of decretals, convened two papal consistories (Paris, Reims), and was the architect of one of the chief arms of the papal judicial system: papal judges-delegate. He also presided over three councils in 1148 (Trier, Reims, and Cremona). Through these activities Eugenius sought to further the Gregorian reform: libertas ecclesiae (freedom of the church from lay control), the moral reform of the clergy, and the primacy of Rome over all churches.

The majority of Eugenius's papal letters have been edited in several collections: Patrologia Latina (180), Acta Pontificum Romanorum Inedita, and the Papsturkunden series; see also Jaffé (1885-1888). For Eugenius's activities as the Pisan vicedominus, see Regestum Pisanum (1938). Two letters have survived from Eugenius's tenure as abbot (Patrologia Latina, 182).

See also Crusades; Laws Canon

CHARLES D. SPORNICK

Acta Pontificum Romanorum inedita, ed. Julius von Pflugk Harttung. Tubingen and Stuttgart: Fues, 1880-1886.

Bernard of Clairvaux. Five Books on Consideration: Advice to a Pope, trans. John D. Anderson and Elizabeth T. Kennan. Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, 1976.

—. Epistolae. In Sancti Bemardi opera, ed. J. Leclercq and Henri Rochais, Vols. 7-8. Rome: Editiones Cistercienses, 1977.

Boso. Le Liber Pontificalis, ed. L. Duchesne. Paris: E. de Boccard, 1955.

Gerhoch of Reichersberg. Letter to Pope Hadrian about the Novelties of the Day, ed. Nikolaus M. Haring. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 1974.

Jaffe, Phiiipp. Regesta Pontificum Romanorum. Leipzig: Veit, 1885-1888.

John of Salisbury. Historia Pontificalis: Memoirs of the Papal Court, trans, and ed. Marjorie Chibnall. London and New York: Nelson, 1956.

Mansi, Giovan Domenico, ed. Sacrorum Conciliorum, Vol. 21. Venice: Zatta, 1759-1798.

Otto of Freising. Chronica sive Historia de duabus Civitatibus, ed. A. Hofmeister, Hannover: Hahn, 1912.

Papsturkunden Series, ed. Paul Kehr, Johannes Ramackers et al. Patrologia Latina, 180, pp. 1013-1642; and 182, pp. 547-549.

Regestum Pisanum, ed. Natale Caturegli. Rome: Istituto Storico Italiano per il Medio Evo, 1938.

Wibald of Stablo. Epistolae, ed. P. Jaffé. Berlin, 1864.

Dimier, Anselme. "Eugene III." In Dictionnaire d'histoire et de géographie ecclésiastiques, Vol. 8, pp. 1349-1355.

Gleber, H. Papst Eugen III. (1145-1153) unter besonderer Berücksichtigung seiner politischen Tätigkeit. Arnstadt: O. Bottner, 1936.

Haring, Nikolaus. "Notes on the Council and Consistory of Rheims (1148)." Mediaeval Studies, 28, 1966, pp. 36-59.

Maleczek, Werner. Papst und Kardinalskolleg von 1191 bis 1216. Vienna: Verlag der Osterreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1984.

Partner, Peter. The Lands of Saint Peter: The Papal State in the Middle Ages and the Early Renaissance. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1972.

Tellenbach, Gerd. Church, State, and Christian Society at the Time of the Investiture Contest. Oxford: Blackwell, 1955.

Etugenius of Palermo (c. 1130-c. 1202) was a highly placed official, an accomplished poet, and a translator of scientific and literary works. He facilitated east-west cultural transmission in the kingdom of Sicily when it was still significantly polyglot.

Eugenius was a member of the Italian-Greek nobility that had filled important positions since the early days of Norman rule; he was the son, nephew, and grandson of officials who had attained the rank of admiral, or emir—a title that was not exclusively naval—and whose work must have required a knowledge of Arabic. From 1174 to 1190, Eugenius served as master of the duana baronum, a royal financial office, then based in Salerno, for the mainland part of the kingdom. Eugenius himself was made an admiral in 1190 by the newly crowned king, Tancred; he was a major figure at the court in Palermo during the reigns of Tancred and Tancred's immediate successor, William III. Along with others close to William, Eugenius was arrested at the end of 1194; he was charged with conspiracy against Henry VI and was imprisoned in southern Germany. By July 1196, however, he was back in the kingdom and was serving, in Apulia and without the title of admiral, as a senior subordinate of the imperial legate Conrad of Querfurt. He may also have been the Eugenius who was master chamberlain for Apulia and Terra di Lavoro from 1198 to at least 1202; this is less certain but is usually accepted. The date of his death is unknown.

Eugenius's multilingualismiliiigualism borl considerabie fruit. He is assumed to be the Eugenius who assisted the author of the first Latin translation (c. 1159) of Ptolemy's Almagest, an astronomical text transmitted in Greek and Arabic manuscripts; his fluency in all three tongues is noted in the translator's acknowledgment. His own Latin translation of Ptolemy's Optics from its Arabic version (the original Greek is lost), which seems to have been contemporary with the translation of the Almagest, was used by Roger Bacon in the thirteenth century and survives in more than a dozen manuscripts. Eugenius's Latin translation of the cryptic Prophecy of the Erythrean Sibyl from Greek is now known only through its very popular thirteenth-century Joachite reworking by John of Parma or an associate, but significant portions of this apocalyptic text are believed to belong to Eugenius's original. Eugenius also prepared or at least commissioned, probably during his later years at court, an edition of the Greek "mirror of princes" Stephanites and Ichnelates, itself a translation of the Arabic Kalila wa-Dimna (selections from the Indian Panchatantra or Fables of Bidpat).

Eugenius is the front rank of the Greek poets of medieval Italy. From his larger production, twenty-four poems survive, preserved in a single fourteenth-century manuscript written at the famous monastery of San Nicola at Casole near Otranto. These poems are in metrically careful twelve-syllable iambics; some are epigrams, but most are longer reflections on ethics and other aspects of the human condition. The two longest and best-known are the first and last: When he was in prison (number 1, in 207 lines) and To the most renowned and trophy-holding king William (number 24, in 102 lines, a panegyric probably addressed to William I). Other noteworthy pieces include an elegant description of a locally common water lily (number 10); a derogatory rejoinder to the ancient satirist Lucian's Praise of the Fly (number 15); and the mildly didactic On kingship, perhaps written for the young William III (number 21).

In the unique copy of Peter of Eboli's Liber ad honorem Angus ti, the caption to a group portrait of the alleged conspirators of December 1194 names Eugenius, among others. But more names are listed than there are faces in the illustration, and it is not clear which if any of those depicted is meant to be Eugenius. Specimens of his signature survive in official documents. A modern scholarly attribution to Eugenius of the writings of his now anonymous contemporary, called Hugo Falcandus, has found little favor.

See also Greek Language and Literature; Peter of Eboli; William III

JOHN B. DILLON

Gigante, Marcello, ed. and trans. Eugenii Panormitani Versus iambici. Istituto Siciliano di Studi Bizantini e Neoellenici, Testi, 10. Palermo: Istituto Siciliano di Studi Bizantini e Neoellenici, 1964.

Holder-Egger, O., ed. "Italienische Prophetieen des 13, Jahrhunderts, 1." Neues Archiv der Geselbchafi für ältere deutsche Gescbichtskunde, 15, 1890, pp. 141-178. (Critical edition of Vaticinium Sibillae Eritheae [sic] and similar texts.)

Lejeune, Albert, ed. and trans. L 'Optique de Claude Ptolemee dans la version latine d'après I'arabe de I'émir Eugène de Sicile, augumented ed. Collection de Travaux de I'Academie Internationale d'Histoire des Sciences, 31. Leiden: Brill, 1989.

McGinn, Bernard, trans. "The Erythraean Sibyl." In Visions of the End: Apocalyptic Traditions in the Middle Ages. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979, pp. 122-125, 312-313. (Annotated selections from the Eugenian portions of this text.)

Billerbeck, Margarethe, and Christian Zubler, eds. and trans. Das Lob der Fliege von Lukian bis L. B. Alberti: Gattungsgeschickte, Texte, Übersetzungen, und Kommentar. Sapheneia: Beiträge zur Klassischen Philologie, 5. Bern: Peter Lang, 2000. (See especially pp. 39-41, 173-179.)

Falkenhausen, V. von. "Eugenio da Palermo." In Dizionario biografico degli Italiani, Vol. 43. Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 1993, pp. 502-505.

Gigante, Marcello. "II tema dell'instabilità della vita nel primo carme di Eugenio di Palermo." Byzantion, 33, 1963, pp. 325-356.

—. "La civilta letteraria." In I bizantini in Italia, ed. Guglielmo Cavallo et al. Antica Madre, 5. Milan: Scheiwiller, 1982, pp. 613-651. (See especially pp. 628-630.)

Jamison, Evelyn. Admiral Eugenius of Sicily: His Life and Work and the Authorship of the Epistola ad Petrum and the Historia Hugonis Falcandi Siculi. London: Oxford University Press for the British Academy, 1957.

Loud, Graham A. "The Authorship of the History." In The History of the Tyrants of Sicily by "Hugo Falcandus" 1154-1169, trans. Graham A. Loud and Thomas Wiedemann. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1998, pp. 28-42.

McGinn, Bernard. " Teste David cum Sibylla: The Significance of the Sibylline Tradition in the Middle Ages." In Women of the Medieval World: Essays in Honor of John H. Mundy, ed. Julius Kirshner and Suzanne F. Wemple. Oxford: Blackwell, 1985, pp. 7-35. (Reprint, Apocalypticism in the Western Tradition. Aldershot: Variorum, 1994, article 4.)

Ménager, Léon-Robert. Amiratus—'Aμηρâς: L'émirat et les origines de I'amirauté. Paris: SEVPEN, 1960. (See especially pp. 75-78.)

Sjöberg, Lars-Olof. Stephanites und Ichnelates: Überlieferungsgeschichte und Text. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis, Studia Graeca Upsaliensia, 2. Stockholm: Almqvist and Wiksell, 1962. (See especially pp. 103- 111.)

Eusebius (Eusebius of Vercelli, saint, d. 1 August 371) was born in Sardinia and was educated and ordained as a lector in Rome. Subsequently, he served as the first bishop of the church in Vercelli. Eusebius was the earliest bishop in the west to unite monastic and clerical life; he is also regarded as one of the foremost defenders of Saint Athanasius and orthodoxy against the heterodox Arians. His surviving work includes three brief letters, and Saint Jerome also attributes to Eusebius a Latin translation of Eusebius of Caesarea's commentary on the Psalms, which is no longer extant. Previously, scholars ascribed the Codex Vercellensis to him, although this attribution is controversial.

JENNIFER A. REA

De Clercq, V. C. "Eusèbe de Verceil." In Dictionnaire d'histoire et de géographie ecclésiastiques, Vol. 15, pp. 1477-1483.

Levine, Philip. "Historical Evidence for Calligraphic Activity in Vercelli from Saint Eusebius to Atto." Speculum, 30, 1955, pp. 561-581.

Eustace (Eustachius, Eustasius; thirteenth century) of Matera, an Apulian, was a judge at Venosa and a partisan of the Swabian monarchy in the kingdom of Sicily. He was exiled by the new Angevin regime in late 1269 or early 1270, and during the year 1270-1271 he composed a long Latin poem in elegiac distichs, Planctus Italie (Italy's Laments), detailing the fate of various cities in Sicily and elsewhere in Italy. In this work, Eustace used artful rhetoric and traditional elements of praise of cities. Planctus Italie was known to Dionigi of Borgo San Sepolcro and to Paul of Perugia; through the latter, it became one source of Boccaccio's antiquarian learning. Evidently, Planctus Italie extended to as many as fourteen books, but today it is preserved only in fragments. The longest extant fragment deals with the sack of Po tenza following its unsuccessful revolt in 1269. Other surviving passages provide topographic information, mention local crops and other products, and give etymologies for the names of cities and regions.

By the early fifteenth century Eustace was also considered the author of an anonymously transmitted work, De balneis Puteolanis, which is not entirely dissimilar to Planctus Italic. However, De balneis is now assigned to Peter of Eboli.

See also Latin Literature

JOHN B. DILLON

Altamura, Antonio. I frammenti di Eustazio da Matera. Archivio Storico per la Calabria e la Lucania, 15, 1946, pp. 133-40. (Reprinted in Studi di filologia medievale e umanistica. Naples: S. Viti, 1954, pp. 81-91.)

D'Amato, Jean M. "A New Fragment of Eustasius of Matera's Pianctus Italie." Mediaeval Studies, 46, 1984, pp. 487-501.

Imbnaru, Maria Teresa. Appuntt di letteratura lucana. Potenza: Consiglio Regionale della Basilicata, 2000, pp. 5-10, 198.

Petrucci, Livio "L'Eustachio di Matera di A. N. Veselovkij." Stud: Mediolatini e Volgari, 28, 1981, pp. 153-172.

Schaller, Hans Martin. "Eustachius de Matera und Pandolfo Coilenuccio." In Stauferzeit: Ausgewäklte Aufsätze. Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Schriften, 38. Hannover: Hahn, 1993, pp. 144-163.

Exarchate of Ravenna was the name given to the Byzantine government, or regime, with its seat in Ravenna, that was developed between the completion of Emperor Justinian's reconquest of Italy and the fall of Ravenna to the Lombards in 751.

The concept seems to have developed in the decades following Justinian's death (565), at a time when the two major areas reconquered by imperial forces were seen as in continuing peril: North Africa, retaken from the Moors and Berbers; and Italy, retaken from the Lombards. There was a precedent for the exarchate, since Justinian had given extraordinary powers to certain commanders, such as Belisarius and Narses. The traditions established earlier under Diocletian and Constantine had decreed a strict separation of military and civil powers in individual offices; but in a break with this tradition, Belisarius and Narses were given comprehensive authority not only to command troops but also to preside over administrative and judicial functions. The title exarch—literally, "ruler outside," or beyond the frontiers—is perhaps closest to the modern titles viceroy and governor-general. Just when it was framed or when it began to be used is not clear; some scholars think that this occurred at the time of the Lombard invasions in 568, but in any case the title seems to have been in general use by the last decades of the sixth century. At that time, the eastern Roman, or Byzantine, empire was fighting to survive, specifically in the east: the western territories were considered remote, somewhat alien, and all but supplemental rather than integral parts of the empire. Emperor Maurice (582-602) is sometimes credited with having explicitly created the two exarchates (first mentioned in documents in 584), and some scholars have seen them as prototypes for the form of military redistricting, the themes, applied to the territories of the empire's heartland in the seventh century.

The African exarchate was identified with its seat in Carthage, and the Italian exarchate was, in the same way, clearly tied to the continuance of Ravenna as the functioning capital of Italy. The enclave around Ravenna held out, alone, against the Lombard tide that had engulfed the rest of northern Italy and even parts of the center. Although the term esarcato came to refer geographically to the region immediately around Ravenna, the power of the exarchate extended through the southern regions of Italy remaining in Byzantine hands. Rome itself remained imperial, if sometimes precariously; its government was directly under the popes, but the popes were considered subjects of the emperor and therefore theoretically dependant on the exarch, who was directly responsible only to the sovereign in Constantinople. At times, when popes were disobedient, the exarchs were ordered to chasten them, as in the case of Pope Martin I. Conversely, several exarchs rebelled against Constantinople. While there are gaps in our knowledge of the holders of this office, we know of the names of some twenty incumbents.

The exarchs could do litde against their sometimes aggressive Lombard neighbors; and when the resurgent Lombard forces of Aistulf seized Ravenna in 751, no attempt was made to reconstitute the exarchate in the imperial territories of southern Italy, which were organized instead as themes and were eventually brought together under a supreme official called the katepan.

See also Belisanus; Byzantine Empire? Lombards; Martin I, Pope; Narses; Ravenna

JOHN W. BARKER

Diehl, Charles. Etudes sur I'administration byzantine dans I'exarchat de Ravenne (568-751). Paris: E. Thorin, 1888. (Reprint, New York: Franklin, 1959.)

Guillou, André. Régionalism et indépendence dans I'empire byzantin au VII siècle. Rome: Istituto Storico Italiano per il Medio Evo, 1969.

Hodgkin, Thomas. Italy and Her Invaders, 376-814, Vols. 5-7. Oxford: Clarendon, 1880-1899. (Reprint, 1967.)

Jones, A. H. M. The Later Roman Empire, 284-602: A Social, Economic, and Administrative Survey, 3 vols. Oxford: Blackwell, 1964. (Also Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1964, 2 vols.)

Ezzelino III da Romano (25 April 1194-1259), the son of Ezzelino II of Monaco, was a member of the Italian aristocracy, a military leader, and a governor who eventually became lord of Verona, Vicenza, and Padua. When Ezzeiino III entered into his inheritance, the Trevisan March was politically unstable and awash in blood feuds, a situation that Ezzeiino used to his advantage. In 1225, in an alliance with some local families, he seized control of Verona; in 1226, he was made podestà. In the next few years Ezzeiino allied himself with the Lombard League, which resisted the attempt by Emperor Frederick II to subdue the northern Italian communes. Ultimately, however, Ezzeiino was forced to resign as podestà; and as the Lombard League came to favor a faction opposed to him, he turned to Frederick for support. Ezzeiino recaptured Verona in 1232; in 1236, when the emperor sent military reinforcements to aid him, Ezzeiino also conquered Vicenza and Padua. In 1237, he helped the emperor defeat the Lombard League at Cortenuova. For the next twenty years, Ezzeiino was the most powerful force in the March, often maintaining his authority and imposing his will through brute force. He cemented his alliance with the emperor in 1238 when he married Frederick's illegitimate daughter Selvaggia.

Ezzelino had formed his alliance with the emperor not because of any ideological adherence to the Ghibelline cause but because he perceived, correctly, that this alliance would favor his own interests. Likewise, he was not attracted to titles and typically did not hold office in the communes he controlled, preferring instead to act as a party leader, manipulating the councils of the cities to achieve his purposes. By the time of Frederick's death in 1250, Ezzelino was in a position to survive in power without the emperor's support. In 1254, however, Pope Innocent IV declared Ezzelino and his northern Italian ally Uberto Pelavicini heretics, excommunicated them, and launched a crusade to oust them from power. Ezzelino was in all likelihood not a heretic, as he seems to have evinced little interest in religious matters except as they constituted a threat or an aid to his own power. After Innocent died, his successor, Pope Alexander IV, continued the crusade and enlisted the Venetians, who were wary of Ezzelino's power and proximity. Pelavicini suddenly left Ezzelino and made an alliance with the papal forces. Ezzelino was captured at the battle of Cassano in 1259, and he died in captivity shortly thereafter, reportedly after refusing food and medical attention.

Ezzelino was legendary for his cruelty and became a symbol of the ferocious tyrant, especially to his Guelf enemies. The Guelfs' propaganda painted him as inhuman; Giovanni Villani, for example, wrote that he "was the most cruel and feared tyrant that ever existed among Christians." Salimbene of Parma wrote that Ezzelino "was truly of the body of the devil and a son of iniquity. . . . He was the worst man in the world." While most scholars now believe that the Guelfs' portrayal was exaggerated, they do not doubt Ezzelino's willingness to resort to force, intimidation, and cruelty in order to achieve his ends. Ezzelino, however, was very much a man of his time, ably using the factions of Italian politics and the communal system of government in northern Italy in his determined pursuit of power.

See also Cortenuova, Battle of; Frederick II Hohenstaufen; Innocent IV, Pope; Lombard Leagues

V. S. BENFELL

Fasoli, G., et al„ eds. Studi Ezzeliniani. Rome: Isticuto Storico Italiano per il Medio Evo, 1963.

Larner, John. Italy in the Age of Dante and Petrarch 1216-1380. London: Longman, 1980.

Rapisarda, M. La signoria di Ezzelino da Romano. Udine: Del Bianco, 1965.