II.

The Greek Sports Craze

To be healthy is the very best thing for anyone in life . . .

—SIMONIDES, POET, SIXTH CENTURY B.C.

AS IF IT weren’t enough for the ancient Greeks to have established the foundations of Western philosophy, geometry, drama, art, and science, we can also thank them for creating our modern passion for sport. “There is no greater glory for any man alive,” writes Homer in The Odyssey, sounding like a TV commentator on a roll, “than that which he wins by his hands and feet.” The Greeks’ love of competitive athletics is now securely embedded in international culture: not only our modern Olympic Games, revived in 1896 by the French baron Pierre de Coubertin, but the slew of world cups and Super Bowls, our opens and our grand slams, hark back to those energetic pagans—as does our correlating obsession with youth and the body beautiful. All of our fad diets and health magazines, our workout machines and Pilates regimes, were anticipated by the harmony-loving Greeks, whose artists devoted their lives to establishing the perfect proportion of thigh to femur. (In their admiration of physical perfection, the ancient Greeks were guiltlessly superficial. Indeed, the most enduring character of Greek mythology today may well be Narcissus.) Sport was the core of every Hellenic education; every provincial city had its gymnasium, its wrestling school, and its municipal athletic games.

It was an obsession that mystified other ancient people. “What sort of men have you brought us to fight?” a Persian general asked King Xerxes at the height of the invasion of Greece in 480 B.C. He had just learned that, while only a handful of Spartan soldiers were bravely defending Greece at the pass of Thermopylae, tens of thousands of able-bodied men were actually away at the Olympic Games, watching a wrestling final. When the general learned that the only prize was an olive wreath, he did not hide his contempt.

Why did this sports mania take such a deep hold in Greece, rather than in ancient Gaul, say, or in Libya, or Britain? It could be said that athletics combined the two vital currents of Greek life: the love of physical exercise and a rabid, relentless competitiveness.

Ancient Greece was the original Land of the Great Outdoors: thanks to the benign climate, Greeks lived en plein air, running through the dizzy crags of their mountainous land, swimming in the rivers and glassy blue depths of the surrounding seas. But the fragmented geography, divided by rugged valleys and inlets, also fostered divisions. Over one thousand independent states grew up around the mainland and islands, each centered on a single city, each proud of its traditions, each vying desperately for the slender natural resources of Greece. National competitiveness plunged the land into endless warfare, and was reflected within each city on a daily basis—not just in the chaotic internal politics of most states, but by the flamboyant individualism of its citizens. As Homer said, Greeks felt a personal mission “to always be the first and surpass everyone else.”

Imagine the Wall Street bull pit conducted on the beach in California and you might have an idea of the abrasive male one-upmanship that emerged by the Aegean.

Greeks loved to compete over everything—drama, pottery, oratory, poetry reading, sculpture. Travelers held eating races in inns, doctors would vie over their surgery skills and thesis presentations. The first beauty pageants were Greek, for both males and females, as were the first kissing competitions (held in Megara, but for boys only). It was inevitable that Greeks would test one another in their most beloved pastimes.

Any excuse was good enough to hold a sports meet. The Greeks held races and athletics at weddings and at funerals. They took wagonloads of athletic equipment with them on military campaigns. And they competed at the myriad religious festivals that punctuated the annual calendar in this era before weekends. The Olympics were born from one of these cult occasions. The details are shrouded in myth: Ancient writers weighed up several contradictory tales involving gods and heroes, with the geographer Strabo wisely concluding that they were too confusing to be of any value. The current consensus of archaeologists is that Olympia had been a religious site dedicated to the Earth goddess Gaea since 1100 B.C. Some time around 1000 B.C., an agrarian festival at Olympia was combined with casual footraces dedicated to Zeus in a village atmosphere. In 776 B.C.—at least this was the date accepted by ancient tradition—the first official sports meeting was instituted at the sanctuary. We do not know precisely why Olympia’s prestige grew so rapidly—it was probably thanks to Zeus’s oracle there, believed to predict the result of wars—but by the sixth century B.C., the Olympic Games were regarded as the ultimate festival, towering in popularity over all other events. Held every four years to coincide with the second full moon after the summer solstice, they “attracted the best of the best, and the most celebrated of the celebrated.”

A Barbarian in the Gym

A FEW OF the more sophisticated Greeks could imagine how peculiar their sports craze might seem to outsiders like Xerxes and his general. There is a hilarious dialogue written in the second century by the prolific satirist Lucian, subtitled On Physical Exercises. In it, a fictional barbarian prince named Anacharsis is being given a sightseeing tour of the Lyceum, one of the four great gymnasiums of Athens. As mentioned, Lucian was an inveterate sports fan—he went to the Olympic Games at least four times—but as a writer he had the unusual ability to observe his own culture with critical distance. Anacharsis—a self-confessed “good-natured barbarian”—is the original Noble Savage, and his bemused reactions might echo our own if we were somehow teleported to classical Athens. (A similar skit today might involve a Yanomamo Indian visiting a gym in New York City.)

“I’d love to know what the point of all this is,” the visitor says, after he is led into the famous riverside gymnasium, where dozens of naked young men are in a courtyard, running on the spot, kicking the air or jumping back and forth to warm up. “To me, it looks like madness—these maniacs should all be locked up.”

As he is escorted on, more shocking scenes unfold, involving the contact sports that were the core of the Greek phys ed curriculum. Wrestlers are murderously tossing and strangling one another, while boxers are knocking out one another’s teeth.

“Why are your young men behaving so violently?” Anacharsis asks his guide, the Greek law-giver Solon. “Some of them are grappling and tripping each other—some have their hands around one another’s throats—others are wallowing in pools of mud, writhing together like a herd of pigs. But the first thing the boys did when they stripped naked, I noticed, was to oil and scrape each other’s bodies quite amiably, as if they were actually the best of friends. Then, something came over them—I don’t know what. They put their heads down and began to push, crashing their foreheads together like angry rams.

“Look there! That young man has lifted the other one right off his legs, then dropped him on the ground like a log. . . .

“Why doesn’t the official in charge put an end to this brutality? Instead, the villain seems to be encouraging them—even congratulating the one who threw the blow!”

The Greek simply chuckles condescendingly: “What is going on is called athletics,” he explains. Perhaps it does look a little rough, Solon admits. But wouldn’t Anacharsis rather be one of these strapping young athletes, grimy, bloody-nosed, and sunburned as they are, than a sickly, pasty-skinned bookworm—one of the sorry wretches whose bodies are “marshmallow soft, with thin blood withdrawing to the interior of the body”?

It’s a question that echoes through history—reworked by Charles Atlas in advertisements, many centuries later, about the sunken-chested “90 pound weaklings” of America who have sand kicked in their faces. Indeed, the remark that helped start physical culture in the 1950s was eerily presaged by the author Philostratus in the third century A.D.: “I contend that a sunken chest should not be seen,” he writes, “let alone exercised.”

The Ancient Workout: A User’s Guide

WHAT WAS IT like to exercise at an ancient gymnasium? It’s safe to say that at every step of the way, the experience was quite different from that of the average modern health club.

In fact, the Greek gymnasium, despite the name, bears only a hazy relationship to a contemporary gym. It was less a specific building than a public sports ground, the signature feature of which was a running track. This large, open-air space was enclosed by column-lined arcades, including a covered running track for use in bad weather; it was usually placed near a river where athletes could swim, and always attached to a palaestra, or wrestling school. What’s more, sports was only one aspect of this complex’s function. The gymnasium was the ultimate Greek social center—and an exclusive male domain (only in Sparta and some other progressive Greek cities were young women given separate physical training). It was the lungs, heart, and brain of every polis: many had elegant gardens, parks, libraries, even, in one case in Athens, a museum of natural science. The gymnasium was where young boys of all social classes came for their primary education, where teenagers of the upper classes remained for military training, and where they generally had their first love affairs, with older men who acted as mentors. The testosterone-fueled ambiance remained addictive for older Greek men: authors often joked about “codgers” becoming figures of fun for trying to wrestle with golden-haired youngsters or join the dance classes that were a key part of education.

We can piece together the routine of an Athenian athlete preparing for the Olympics—let’s call him Hippothales, a twenty-five-year-old wrestler in the mid–first century B.C. Like all Olympic hopefuls, he was obliged by the official regulations to devote himself to a training schedule in his home gymnasium for a full ten months before the start of the Games. Using the literary and archaeological evidence, we can follow Hippothales arriving at the Lyceum, the same gymnasium toured by the fictional Anarchasis.

HIPPOTHALES, DRESSED IN a tunic and carrying a pouch with his modest athletic gear, would enter the gymnasium through an antechamber flanked by impressive bronze statues of Hermes and Apollo. He makes a libation at the shrine of Hercules, patron of all athletes, then strolls along a marble arcade cluttered with artifacts—captured enemy helmets, gilt-edged shields, marble sundials, and a statuette of Eros, another Greek god who was a habitué of the gymnasium—before reaching the apodyterion, or undressing room. This long narrow hall looking out onto a courtyard is a hive of activity. Its stone benches are piled high with athletic apparatus—discuses in their slings, jumping weights, leather wrestling caps, blunt practice javelins—along with the occasional skinned hare an athlete may have purchased from a local hunter for dinner. It’s so crowded that Hippothales has trouble even finding a space to undress. Despite the pre-Olympic hype, ordinary citizens are not kept at bay from the changing room during training sessions—the gymnasium is Athenians’ piazza, their school and university rolled into one—creating the boisterous atmosphere of a social club. Old friends meet and catch up on the gossip, curious spectators gape at celebrities, self-appointed experts examine the physiques of unknown contenders. Mathematicians are at work with their students on geometrical problems, philosophers warble about the immortality of the soul or the role of athletics in an ideal society, while artists are gathered for life drawing classes. Michelangelo had to learn his anatomy from the autopsy of corpses; Greek painters and sculptors developed their brilliant skills studying athletes during their calisthenics. In fact, it feels as if all of Athens has converged on the changing room. Young boys toss knucklebones and walk their slavering hunting dogs. Fighting cocks are sparring in a corner, to the roars of gamblers. And this social melting pot is also the perfect setting for sexual advances: gymnasiums are renowned pickup spots, where older men swoop on flirtatious adolescents.

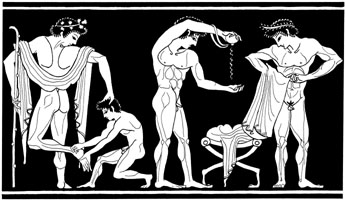

Inside the undressing room: The figure on the left is enjoying a foot massage; the athlete in the middle is pouring oil from a container for his rubdown. (From an Athenian drinking cup, c. 500 B.C.)

Once Hippothales finds a corner, changing does not take long: his leather sandals and chiton, or light wool tunic, are flicked off in an instant. Greeks were well aware that their exercising in the nude was a unique habit, and their historians tried to explain how loincloths were abandoned. Some authors said an Athenian runner had once let his loincloth slip during a footrace and had tripped over it, prompting city elders to proclaim that all athletes should henceforth perform naked. Others thought the practice began when a runner named Orsippos of Megara decided he could race faster without it—and proved it, by winning the Olympic sprint in 720 B.C. Modern historians have tried to interpret the nudity as a throwback to ancient initiation rituals, religious cult practices, or even prehistoric hunting traditions, when men would cover themselves with oil to mask their scent. But the real answer may be more simple: Nudity appealed to the sheer exhibitionism of Greek athletes, giving them a chance to show off their physiques, and the naked male form became utterly ingrained in gym culture—in fact, the very word gymnos means “naked.” Few cultures have been quite so shamelessly vain and superficial in their worship of physical perfection as the Greeks. Flabbiness and pale skin were subjects of derision, and vase paintings show fat boys being mocked by their peers. Whether conscious or not, the Greeks’ nudity was also potently symbolic in its removal of social rank. This fact shocked other cultures as much as the Greeks’ immodesty, and the fear that naked workouts would promote sexual degeneracy. Foreign aristocrats were appalled that wealthy Greeks would want to remove all signs of their social status and risk public humiliation against social inferiors. Even a larger-than-life hero like Alexander the Great, ruler of Macedonia, famously refused to take the field in athletics: He would only compete, he said, against other kings.

HIPPOTHALES DROPS HIS tunic and sandals into a basket and hangs it from a stone peg—along with his few personal belongings, probably just a flask of perfume and metal skin scraper for the baths, and his signet ring, which might injure wrestling opponents. He gives one of the attendants a bronze coin to look after his goods, since thieves commonly work the busy changing rooms. The philosopher Diogenes once ran into a shady character lurking in the shadows and quipped, “Are you here for a rub-down or a robbery?” In Athens, the penalty for these despised parasites is death. Inscriptions have been found in Roman-era baths of curses placed on clothes pilferers (“Do not allow sleep or health to him who has done me wrong. . . .”). They were taken in deadly earnest: some thieves repented when they learned they were cursed, and returned stolen goods.

After stripping down, the next stop for Hippothales is the oiling room. After water, olive oil was the most important single item in ancient Greek life, a sacred balm that had a role to play at every stage of the workout. Athletes virtually swam in the substance, basting themselves in a permanent oil slick before, during, and after exercise. At casual workouts, Hippothales would simply apply the oil himself—it was habitually poured into the left hand and rubbed over the whole body—but today he hires the gymnasium’s “boy rubber” for a few coins. Later, as his Olympic training becomes more serious, coaches and professional masseurs will be poised to give him a more scientific rubdown.

Attendants pour the oil from enormous forty-gallon amphorae into bronze vats, which look like oversized punch bowls standing on three carved legs, with elegant ladles for distributions. Gymnasium-issue olive oil was of relatively low quality, produced locally by farmers in Attica, but finer oil for the table was grown on sacred trees and traded over long distances and rated like vintage wine. Vast quantities disappeared during athletics: a third of a pint per man per day was used, slightly less for boys. Apart from its ritual importance, olive oil conserved an athlete’s body moisture in the heat of the workout and functioned as a tanning lotion. While pale northern flesh fries under a layer of oil, Mediterranean skin slowly browns to the color of fired clay. Some athletes, tanned from head to foot, looked as if they had been slowly roasted on a spit; poets drooled about boys who looked “like finely-wrought bronze statues.”

Happily greased, contestants in the track-and-field events could now dash outside to begin training. But Hippothales, like all others in the contact sports, had one last stop—the powder room, or konisterion, where he would sprinkle his body with dust. For casual bouts, wrestlers might just throw sand on one another’s backs, to provide a decent grip. But the top-class competitors in Athens could choose from a colorful buffet of powders, laid out like exotic spices in wicker baskets around the room, and whose qualities for different skin types were as precisely calibrated as the unguents on sale in any California spa today. According to Philostratus, in his Handbook for a Sports Coach, one claylike powder was particularly good for opening the pores, another an excellent antiperspirant for oily complexions. A terra-cotta powder repaired dry skin, while a yellow dust provided the most becoming sheen—“a delight to see on a body in good shape.” These powders had to be applied evenly, Philostratus stresses—“sprinkled with a fluid motion of the wrist and with fingers spread apart. The dust should fall more in a gentle shower than a thunder burst, so that it covers the athlete’s body like soft down.” Hippothales pays careful attention to the process, since aesthetics have always been crucial in Greek sports. Good health may have been the best thing in life, as Simonides said, but the next best thing (the poet hastily added) was “to be handsome.”

Jump to the Flutes

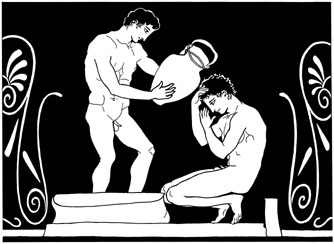

HIPPOTHALES IS NOW ready for his warm-up exercises, many of which are performed to music. Greeks loved to combine the harmony of the body with the rhythms of instruments, creating an incipient form of aerobics. He can drift from one group to another. In open spaces, some athletes are swinging lead weights like dumbbells back and forth to the accompaniment of flutes made from the shinbones of stags. Some troupes march on their toes, jump on the spot, or leap up and kick their buttocks with their heels, all to hypnotic, high-pitched tunes. (In Sparta, where girls could train, one woman claimed on her memorial that she did this last exercise one thousand times.)

Boxers doing warm-up exercises to flute music. (From a Greek amphora, c. 400 B.C.)

We can get an idea of the more rigorous exercise regimes Hippothales might have pursued from an ancient self-help book called How to Stay Healthy, written by the illustrious physician Galen in the second century. The good doctor systematically prescribes chapters on exercises for the legs, arms, and abdomen, each of which is broken down into three subsets: controlled exercises for muscle tone, quick exercises for speed, and violent exercises for strength. In the first group, athletes were advised to carry heavy weights, climb ropes, or extend their arms while their companions tried to pull them down. Quick exercises included rolling back and forth on the ground, running in ever-decreasing circles, and standing on tiptoe and rapidly moving one’s arms up and down. Violent exercises were the same, only using weights and done more vigorously. Runners, for example, would put on increasing amounts of armor as they sprinted along the sacred track.

What was the training for specific sports? We know that boxers converged on a room hung with punching bags, which were made from animal skins stuffed with grain, sand, or fig seeds, then hung from the rafters like pendulous smoked hams. Shadowboxing was extremely popular, and was also a hit with the admiring crowds at training sessions, shouting their support as if a real match were in progress. For Hippothales, a wrestler, the training regime is more structured. We have a good idea of his probable drill, thanks to the survival of a unique shred of papyrus from a do-it-yourself manual found in Oxyrhynchus, an obscure Greek colony in Egypt. (Vulnerable to moisture, most papyri disintegrated over time; some 70 percent of our surviving papyri come from a garbage dump in this town by the Nile, where the bone-dry sands have preserved them through the centuries.) The document lists a series of practice holds and throws, which a wrestling instructor is barking out to his students: “You, put your right arm around his back! You, take an under-hold. You, step across and engage! You, turn around! You, grip him by the balls!”

For Hippothales, the day’s training may wind down with a relaxing game of handball—which Galen called “the most satisfactory, all-round exercise.” Every gymnasium had an enclosed court, where athletes would hit a small leather ball back and forth to themselves, often for hours, to build up their arm strength. Another, more social game, hapastum, involved two or more men throwing a ball over the head of a player in the middle, who tried to intercept it either by jumping or wrestling the other players to the ground. The author Athenaeus describes the genial atmosphere: “A player seized the ball and passed it with a laugh . . . amid resounding shouts of ‘out of bounds,’ ‘too far,’ ‘right beside him,’ ‘over his head,’ ‘on the ground,’ ‘up in the air,’ ‘too short,’ ‘pass it back in the scrimmage.’” The Lyceum of Athens, like other gymnasiums, actually employed a specialist to manage ball play, but we know surprisingly little about what games were popular. Athenian reliefs show athletes bouncing balls on their thighs—looking like today’s soccer stars—and using racquets strung with animal gut to hit a ball against a wall, like an early version of lacrosse. Urania, or “sky ball,” involved someone tossing a ball to a crowd of athletes who jumped up to catch it, like modern basketball players leaping for a rebound.

But what about team ball games? Did Homer play rugby? It was a question, oddly enough, that British historians once seriously considered, hoping beyond hope that their favorite team games had classical origins. “Shall we one day discover a representation of Greek boys playing football?” pined the academic Norman Gardiner in 1930. “The Chinese certainly played football at an early date: the Italians of the Middle Ages had their game of Calzio. . . .” He pointed out that both the Greeks and the Romans had an air-filled ball called the follis, and it seems inconceivable that someone, somewhere, wouldn’t have thought to give it a kick. “For the present we do not know,” Gardiner sighs; “we can only hope for future discoveries.” Today, we are still waiting. The only genuine team game we have any evidence for in the ancient era was developed by the Spartans. It was called episkyros and was played in a large field marked with white stones. The rules are obscure, but it’s clear that two teams tossed a small leather ball back and forth, trying to drive each other back over their defense line. With its aerial to-and-fro and bone-crunching collisions, one historian has compared it with American football played without rules, helmets, or padding. But the game never took off in the rest of Greece.

Tyrants of the Sports Ground

Sharpening an athlete who is naturally excellent

A trainer, with the guiding hand of a god

Can rouse him to enormous fame.

—ANONYMOUS, C. 450 B.C.

IN THE SIXTH century B.C., the teenage Milo of Croton developed his own rustic weight-training program on a farm in southern Italy by lifting a young bull calf every day until the beast was fully grown. Bulked up on this natural Nautilus machine, the original Italian Stallion went on to become the greatest of all Olympic wrestling champions, winning the boys’ event in 540 B.C. and five successive wrestling Olympiads over twenty years—a record never broken in the nearly twelve centuries of the Games.

But most Olympics hopefuls like Hippothales, more pragmatically, hired private trainers. These professionals, called paidotribai, were key figures in the ancient Greek sporting culture, and their services were never more in demand than during the ten-month training period that athletes were obliged to embark on before the Olympic Games. They were usually retired athletes themselves, over forty years old, with practical experience of anatomy, nutrition, medicine, and physiotherapy. The typical coach was rough and poorly educated: some were barely able to sign their own names. But many were sophisticated specialists with their own elaborate exercise programs, or rich men with an abiding passion for sport—or thirst for fame. Reflected glory was potent. The names of top trainers were bound forever with athletes who won the olive wreath at Olympia, recorded on memorials and repeated in hymns. Coaches joined in all the Olympic ceremonies and had a special section in the Stadium; they sat by a champion’s side at the victory banquets and would walk beside him in triumphal processions. Later, they could publicize their techniques—even write their own training manuals.

Some of these celebrity trainers were marvelous characters, whose morale-boosting powers were legendary. At the Olympics of 520 B.C., the boxer Glaucus was about to admit defeat when his trainer bellowed, “Give him one for the plough!”—a reference to the day when Glaucus first proved his strength as a teenager on a farm by straightening a bent ploughshare with his bare hands. The young man apparently bucked up, and with one massive blow felled his opponent like a tree. Other trainers took the adage “Death or victory” to heart. A wrestler named Arrhichion was being choked and was about to raise his finger in surrender, until his trainer yelled, “Oh, what a beautiful epitaph! He never gave up at Olympia”—an echo of a military axiom praising those who never surrender. Arrhichion, inspired by these touching words, fought to the death. Another unnamed coach was so exasperated when one of his wrestlers did attempt to surrender that he rushed forward and stabbed the athlete with a sharp metal instrument, killing him. The coach of Promachus of Pellene used more subtle psychology. Learning that his young charge was desperately in love, the coach pretended that the girl had promised her favors if Promachus emerged victorious at Olympia. Thrilled by this fabricated promise, Promachus won the pankration in 404 B.C. against overwhelming odds.

While many coaches developed their own “scientific” training programs, it was Iccus of Tarentum, an Olympic pentathlon champion in 444 B.C., who was the first to take the next step and write his own textbook. It has disappeared—all we know about it is that it called for moderation in training and diet—but an army of other celebrity athletes followed suit with treatises, written on papyrus scrolls and copied by teams of slaves for booksellers around the Mediterranean. These various ancient training manuals, which once numbered in the hundreds, are the unrecognized antecedents of Buns of Steel, Super Abs, and Total Fitness in Only Two Weeks!

Philostratus’ famous Handbook for a Sports Coach, penned in the third century A.D., was found by accident in an archive near Constantinople in 1844, lost, then rediscovered at an Ottoman manuscript sale fifty years later. Showing us the breadth of trainers’ interests, it includes specialized massages to offset overeating, exercise to treat alcohol abuse, and how to identify an athlete’s personality by his eye color. It explains how to deal with anxiety, insomnia, anemia, excessive perspiring, or the debilitating effects of sex. (Mainly through self-restraint: “What sort of man,” the author asks, “would rather succumb to shameful pleasures than enjoy the wreaths and proclamations of Sacred Heralds?” Those plagued by “habitual nightly emissions” are prescribed special workouts.) The reader learns that it is much healthier to sunbathe when the wind is blowing from the north, when the sun’s rays are “pure and beneficial.” And there is considerable arcane discussion of how to balance the four humors of the body, which were the basis of all ancient medicine. (The ideal athletic temperament was “warm and moist,” the author intones, and thus more obedient—“free from dregs, impurities, and excessive secretions are those in whom the stream of phlegm and gall is scanty.”) Philostratus also rails against the overly theoretical training systems that were plaguing Greek athletics. All ancient intellectuals loved abstract formulas—which led to some bizarre fitness regimes. Even Athenian philosophers invented exercise programs, despite the fact that they had no practical experience. (Which sport created morally upright citizens? they wondered.)

In Philostratus’ day, one popular program called the tetrad system involved an unbreakable four-day athletic cycle, with the second day devoted to extreme training, almost to the point of physical collapse. Its rigidity claimed casualties: having won the Olympic wreath for wrestling in A.D. 209, a Greek-Egyptian champion named Gerentus went off on a celebratory drinking binge. He returned to the gymnasium complaining of a filthy hangover, but his trainer would not permit any break in his grueling regime. In mid-practice, Gerentus dropped dead from a heart attack. Travelers could see his gravestone on the highway outside Athens, warning posterity of the dangers of inflexibility.

Many Greek doctors were appalled at the proliferation of these pseudoscientific manuals and tried to denounce them. The famous Galen acidly pointed out that author-trainers were often failed athletes—half-educated men profiting from the ignorance and gullibility of wannabe champions. He argued that their overspecialized and excessive exercise regimes were doing more harm than good, producing a brutish race of Greek athletes who were both doltish and ugly, their froglike bodies distorted and ill-proportioned. But he had little hope in the war of words. Trainers remained paramount in the gymnasium, and the Greek public’s appetite for fad theories insatiable—especially when it came to diet.

FROM EARLIEST ANTIQUITY, what a top athlete should consume was considered as important as his exercise regime, and Hippothales’ trainer would have come up with a detailed meal plan.

According to nostalgic tradition, the first Olympians shared the simple, balanced diet of the average Greek, supping on thick vegetable soup, bread, cheese, olives, fruit, and honeyed cakes. All that changed when a certain Dromeus of Stymphalos won two footraces at Olympia in 480 B.C. on an all-meat diet. High-protein meals became all the rage—a source of resentment for ordinary Greeks, who could not afford expensive meat. Wrestlers and boxers began to gorge on beef, pork, and lamb, becoming (as the playwright Euripides put it) “the slaves of their jaws and the victims of their bellies.”

Fad diets proliferated. Learned dieticians would debate which fish were healthier, those from the swamps or deep-sea fish? Were fish that ate seaweed better for you, or fish that ate algae? Some advocated pork—provided the pigs had been fed on cornel berries or acorns. Swine raised by the sea were injurious to health; those brought up by rivers were even worse “because they may have fed on crabs.” (Savvy coaches did not just pay atten-tion to what was on the plate, advising their charges to avoid intelligent conversation at mealtimes, as it would spoil their digestion and give them headaches; they also weighed in on the style of after-dinner belching.) Ideas for extreme diets came from all quarters. Charmis of Sparta, an Olympic sprinting champion in 688 B.C., espoused eating nothing but dried figs. Xenophon advised athletes to avoid all bread, the first nonyeast diet in history. The Pythagoreans forbade their athletes to touch beans—but Galen recommended a high-bean diet for gladiators, provided the beans were properly boiled to avoid flatulence. Hippocrates considered cheese to be a “wicked food,” despite the fact that it was supposedly the staple of superhuman Homeric heroes. In the end, much like today’s diet fads, Greek dietary recommendations were so contradictory as to be meaningless.

The Joy of Steam

WHEN THE DAY’S training is over, our exhausted Hippothales, caked with dust and sand, heads for the bathhouse, where fountains spout hot and cold water from lion-head faucets. Several streams usually poured out at head height, like modern showers, into basins, buckets, and hip baths. Once again, olive oil was the all-purpose lotion: athletes used it as the basis for soap and shampoo during bathing, mixing it with detergent powder (they could choose from a lye made of ashes, a fine-grained clay, or an alkali called litron). The sticky blend was then scraped off the skin with the strigil or stlengis—a bronze tool in the shape of a crescent moon. But even after rinsing, an athlete’s muscles went without olive oil only for a second: the sacred liquid was quickly reapplied by masseurs, mixed in with a few drops of perfume distilled from flowers as a deodorant.

One athlete washing another after a workout. (From a Greek drinking cup, c. 475 B.C.)

Some Greek moralists denounced the pampering of the bathhouse for breeding weakness and sloth. They sanctimoniously recalled the days of Homeric heroes, who washed only in wild rivers no matter what the season. Few athletes seemed to agree. The Romans took personal hygiene to a higher level and in the first century A.D. introduced to Greece their far more elaborate thermae, or heated baths, each with a trio of steam rooms and deep pools of varying temperatures. In Athens, they erected vast bathing complexes for both men and women, which combined the sport functions of the Greek gymnasium with restaurants, bars, libraries, and even special booths for prostitutes.