III.

Countdown

• Plastering the dressing room in the Gymnasium: 16 drachmae (Paid to Pasion).

• Weeding and rolling the Stadium running track: 21 drachmae (Paid to Smyrnaios).

• Digging and leveling the long-jump pits: 220 drachmae (Paid to Smyrnaios).

—FROM THE FINANCIAL ACCOUNT FOR PREPARING THE GAMES AT DELPHI, 246 B.C.

EVERY FOURTH SPRING, a trio of sacred heralds were sent out from Elis—the city within whose domain the sanctuary of Olympia lay—to announce the date of the upcoming Games of Zeus. For the Greeks, the arrival of one of these flamboyantly uniformed officials must have been anticipated as a colorful seasonal rite. A herald’s theatrical figure would have been easy to spot at a distance as he picked his way on mule-back through the pastures and river valleys: his robes were royal purple, his head crowned with olive wreaths, and he carried the sacred banner, or caduceus, a staff carved with a pair of copulating snakes used by wing-footed Hermes, messenger of the gods. In his satchel was the schedule for the Games. The date was determined by a complex formula to ensure that the middle day of the five-day festival coincided with the second full moon after the summer solstice. This meant that the Games were usually held in August or early September—the summer lull that came after the annual harvest but before the picking of the olives.

The three heralds, or spondophoroi, were enjoying one of history’s first great travel junkets: hopping separately around mainland Greece and the Aegean islands, they were treated like kings at every step. The hospitality began the moment a herald arrived at a new city’s gates and was met by the local proxenos—the official representative of Elis. The visitor would be bathed, then feast on the finest local delicacies and regional wines. The next day, he would be taken before the city council or assembly, where he would be received with great respect as he read in ringing tones the invitation to the upcoming Games, and the terms of the sacred Olympic Truce. Then came a fine state dinner.

This Olympic Truce was one of the ancient world’s most extraordinary traditions. It imposed an armistice across the land—an almost enchanted ban on the Greeks’ incessant feuding—whose terms were enforced by Zeus himself. During this sacred peace, no military attacks could be made, no judicial cases conducted, nor death penalties carried out. The main purpose was to ensure the safety of athletes and spectators on their journeys to the Games, and to keep the entire district of Elis sacrosanct during the festival. Originally the peace was enforced for one month on either side of the Games, but when visitors started to come from farther afield, from Greek colonies in Italy and Asia Minor, the period was extended to two months. (Remoter cities, far-flung islands, and Greek colonies around the Mediterranean were probably alerted by letter.) Its terms had originally been defined in 776 B.C. for the first Games and inscribed in concentric circles onto a hefty golden discus, which still hung in pride of place in the Temple of Hera at Olympia. And despite some notorious exceptions, the truce was honored.

The heralds generally arrived at least two months before the date of the Games: the sixty-day countdown to the Olympics had officially begun. But for the Olympics organizers themselves—a bevy of provincial aristocrats in the city of Elis—the planning process had gotten under way long before. The festival may have been only five days long. It may have felt to some visitors like little more than inspired chaos. But it was nonetheless the result of elaborate behind-the-scenes organization, without which it would have collapsed entirely. The athletics facilities had to be prepared; judges had to be trained; sponsorship had to be arranged; catering needed to be planned.

Running the Games was a full-time job.

The Hereditary Hosts

FEW PEOPLE TODAY have even heard of the city of Elis. Its ancient ruins, which lie forty miles northeast of Olympia, are now the merest rubble; even in antiquity, it was essentially a sleepy rural outpost. And yet it was the Elians who were the official stewards, for generation after generation, of the illustrious Olympic Games.

This tight-knit coterie of landowners, whose wealth came from cattle- and horse-breeding, might seem an unlikely group to be running the greatest festival of the ancient world, but they held their position through unshakeable Greek tradition. It was King Iphitos of Elis who had first declared the Games in 776 B.C., acting on divine instructions. Greece at the time was wracked by plague and warfare, and in desperation Iphitos had consulted the Delphic oracle. He was told that the only way to end the curse was to celebrate athletic games at Olympia, forty miles from his city. Iphitos did so, and the pestilence disappeared. In the centuries that followed, the ruling class of Elians drew from their own ranks the Olympic judges and micromanaged every aspect of the festival.

A laborer levels the running track. (Adapted from the interior of a Greek drinking cup, c. 425 B.C.)

Luckily, the Elians seem to have been a sophisticated, well-educated, and capable clique, who by the classical era had developed an efficient sporting bureaucracy. There was an all-powerful Olympic Council, made up of two dozen cattle barons with time on their hands, which oversaw the whole festival and made broad decisions on scheduling or adding new events. There was a commission of law codifiers, who passed on the rules from generation to generation. But the most visible and active officials at each Games were the ten Olympic judges—loftily called Hellanodikai, Greek guardians of the law—whose responsibilities were far broader than those of any Olympic judge today.

These ten über-judges would not only adjudicate at sporting events but help organize the day-to-day operation of the Games and even supervise the final training of Olympic competitors. Their duties were divided: three judges were chosen to preside over the equestrian events, three the pentathlon, and three all the other events, while the tenth judge coordinated their efforts. During the festival itself, they could impose fines or order whippings, and all of their decisions were final; only an appeal to the Olympic Council could overturn them, a move no athlete would take lightly. From the time of their selection ten months before the Games, these top officials were permitted to swan about Elis dressed, like the Olympic heralds, in robes of royal purple, a costume that paid honor to King Iphitos, who was sole judge at the first Games. The social jockeying for the jobs must have been intense. Aristocrats all, they were selected from among the Elian ruling class by a complicated, and no doubt contentious, mix of voting and random lot. The position was a valued honor, despite the fact that it was time-consuming, unpaid, and extremely costly. Hellanodikai often found themselves using their own funds to cover unexpected incidentals like hiring extra groundsmen or buying new robes for the priests.

Although the impartiality of the Olympic judges was legendary, the fact that Elians could also compete in the Games did raise the occasional ancient eyebrow. In the tight-knit community of Elis, a judge might well see his own friends or relatives taking the field. Even more strangely, the judges themselves were technically allowed to compete, by entering their own horses in the equestrian events. According to Herodotus, envoys from Elis were sent in 590 B.C. to Egypt, the source of ancient wisdom, asking for advice on tightening up the Olympic rules. The shaven-headed Pharaoh reviewed the regulations and pronounced that, for the judging to be completely fair and avoid all taint of partisanship, Elian citizens should not be allowed to participate as athletes. The envoys politely thanked the Pharaoh for his sage advice but never took it. Still, scandals were remarkably rare. For the most part, the Elian judges were respected and admired, and the Olympics had a reputation as the “cleanest” of all Greek competitions. As one approving Greek sports fan remarked, the Elian officials behaved “as if they were on trial as much as the Olympic athletes, anxious not to commit any errors.”

From Cow Paddock to Stadium

AT LEAST IN one respect, running the Games was easier in the ancient world than the modern. Whereas today the setting for the Olympics traverses the globe—with each host city accepting a new crush of logistical problems to prepare for the extravaganza—the original festival was always held at the same verdant spot. In Olympia, a compact religious sanctuary some forty miles from the host city Elis, the Greek Games had a permanent home for 293 successive Olympics.

Physically, the site was strikingly beautiful—exuding (as one historian put it) “a peaceful charm that we rarely feel in that land of rugged mountains.” Some two dozen marble buildings stood in a fertile alluvial plain, bordered by pine-covered hills to the north, the river Alpheus to the south, and the river Cladeus to the west. The sanctuary’s core, the Sacred Grove of Zeus, was surprisingly small: known to Greeks as the Altis, it was a walled-off enclosure that covered a mere six acres. But it was the greatest pilgrimage center of the pagan world, thanks to three famous temples, dedicated to Zeus, his consort Hera, and his mother, Rhea. Scattered haphazardly in between these edifices were some seventy altars covering the Greek pantheon, the grave of the hero Pelops, and a jumble of statues, memorials, shrines, and civic monuments. The spiritual life of this serene outpost carried on without interruption in the four years between Games, with a staff of around fifty, including (one inscription tells us) three priests, a flutist, a wine pourer, a keeper of the keys, a butcher-cook, and a tour guide catering to a few pious pilgrims and sightseers.

Lovely, Olympia certainly was—but as a venue for a mass gathering, it certainly had its disadvantages. Not only was it in a remote rural area, with an almost total lack of accommodation, but the sporting facilities were surprisingly rudimentary and fell into disrepair in the long period between events. A wrestling school had been built on the fringe of the Sacred Grove in the third century B.C., but the Gymnasium was not added until the first century A.D.; before that date, athletes merely worked out in the fields. A Stadium and horse-racing track lay to the east of the temple complex, but they were not maintained during the off-season; in fact, they were used by local villagers to pasture their sheep and cattle. Hammered by winter rains and baked by summer sun, their banks became overgrown with shrubbery and their tracks uneven. To bring the facilities up to par, every fourth year saw an urgent flurry of spring cleaning at Olympia, and the dreamy torpor of the sanctuary was shattered by an army of workers giving the whole environment a top-to-bottom polish.

Teams of laborers made the forty-mile trip from Elis, leading their mule-drawn wagons along a purpose-built highway, paved with smooth stone and grooved in double ruts for wheels. Heavy supplies such as sacks of fresh white earth and mortar would have been barged the fifteen miles upriver from the west coast of the Peloponnese. Extra hands could be cheaply hired from the many asylum seekers at Olympia—refugees had the right to stay at any Greek sanctuary until their legal matters were settled. Elian artisans, whose skills and experience at Olympia had been passed down from generation to generation, pitched tents in the surrounding fields to create a workers’ camp. In the warm spring sunshine, they began to hoe up the wrestling grounds, lay down fresh white sand, level the running tracks, and dig new pits for the long jump and wells for water.

An inscription found at Delphi, dating from 246 B.C., gives luminous insight into how Greek athletic sites were prepared; it lists laborers’ fees for Delphi’s own prestigious Pythian Games, which were held in different summers from the Olympics. (A modern historian has ingeniously converted the rates into today’s currency, by comparing the cost of olive oil then and today. An amphora of forty liters is known to have cost eighteen drachmas in ancient Athens, while one liter of olive oil today is worth about US $10 in a supermarket. Thus a drachma was worth about $22 in our terms, although when making the comparison it should be kept in mind that a skilled Greek artisan in the time of Pericles was paid only one drachma or $22 a day.) The Greeks’ matter-of-fact professionalism and attention to detail would be manifest in work at Olympia:

• Digging and rolling the practice running track in the Gymnasium: $814 (Paid to Agazalos).

• Repairs to the Stadium entrance: $566 (Paid to Euthydamos).

• Repair to the wall by the shrine of the goddess Demeter: $1,298 (Paid to Kleon).

• Construction of 36 turning posts for the running track: $528 (Paid to Anazagoras).

• Cleaning out and fencing the Kastalian spring with the Gorgon’s head spout: $396 (Paid to Kleon).

• 270 bushels of white earth for covering the covered practice track @ $6.42 per bushel: $1,732.50 (Paid to Agazalos).

In Olympia, which was filled with ancient statuary, art specialists were shipped in to oversee restoration work. Precious metals were given new luster, the colored pediments of the temples retouched. The lion-head waterspouts ringing the roof of the Temple of Zeus often had to be replaced: there were 102 of these once-gracious design features—they were used to drain rainwater in winter—but because they were so heavy, they tended to snap off. Local villagers, meanwhile, rubbed fresh olive oil onto the forty-foot-high statue of Zeus to protect its valuable ivory from moisture. (The workers were known as the Burnishers, and were believed to be descendants of the statue’s original artist, Phidias. They could only do so much. By the second century A.D., when the icon was over five hundred years old, visitors reported that the statue’s framework had become infested with rodents, and that their squeaks were becoming a distraction to the pious.)

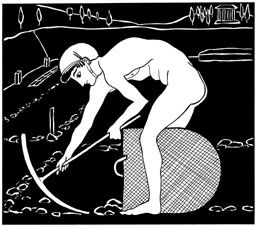

Greek artisans repair statues in a workshop. (From a Greek drinking cup, c. 380 B.C.)

Catering, meanwhile, was put in the hands of private enterprise. Olympia was situated in a sparsely populated rural area, so itinerant vendors flocked there to provide for the captive market. These vendors were required to have licenses, and the Elians appointed a commissioner of marketers to impose on-the-spot fines for shoddy merchandise or price gouging. Merchants came to oversee the construction of their booths and bring teams of livestock to be penned for sacrifices and banquets. Local farmers supplied the wood, and the air was filled with the sounds of carpentry.

The festival was taking shape—and it resembled a sprawling fairground. But impressive as it was, this hive of activity was still considered secondary.

The real buzz was back in the city of Elis, where, a full month before the Games, the hopeful athletes had begun to arrive.