XII.

No Philistines in the Stadium

Zeus, protect me from your guides at Olympia!

—VARRO, ROMAN ANTIQUARIAN AND INVETERATE SIGHTSEER, C. 30 B.C.

IN TERMS OF artistic wealth, Olympia, with its gilded temples full of artwork and its illustrious sculpture gardens, contained more masterpieces per square foot than anywhere outside the Acropolis of Athens. The author Pausanias devotes fully two of the ten books of his second-century-A.D. travel guidebook, The Description of Greece, to the splendors of this national gallery, which lured erudite sightseers all year round. During the Games, however, with teeming multitudes of the pagan faithful on hand, the reverent buzz of art appreciation itself reached a passionate intensity. Even modestly educated Greek sports fans considered themselves connoisseurs of art, and judging from the ancient accounts, the act of tourism was pursued as vigorously as any blood sport during downtime between Olympic events. The city of Elis appointed volunteer guides—called exegetai or mystagogi, “those who explain the sacred places to strangers”—to assist the throngs. Pausanias says he got some of his juiciest stories from a helpful guide named Aristarchos, but other writers like Varro and Plutarch found the guides to be pushy and verbose, repeating their spiels by rote, ignoring questions, and inventing ludicrous tales. “Abolish lies from Greece,” wrote Lucian, “and all the tour guides would die of starvation, since no visitor wants to hear the truth, even for free.”

Today, we modern tourists are lucky to be able to view some of the most celebrated statues of ancient Olympia on location at its museum. (German excavators in the 1870s made a groundbreaking agreement with the Greek government to leave their finds inside the country, rather than purloining them as the British Lord Elgin had done with the Parthenon’s marbles fifty years earlier, or as the French would later do in Delphi.) Of course, the displays represent the merest fraction of the artwork that sports fans once enjoyed; most of Olympia’s masterpieces were looted or destroyed by Christians toward the end of the Roman Empire. Fortunately, we can use Pausanias’ guidebook to visit the site as it looked then. Pausanias was the consummate ancient tourist, wealthy, learned, and somewhat pedantic, who worked his way across Olympia listing every frieze, sculpture, and relic. The afternoon of day three, while the boys’ events were being held, must have been the ideal time for a little cultural tourism. After a light lunch of perhaps bread, fruit, and wine, a sightseer would give a few coins to one of the local guides—hoping not to be too exasperated by his prattle—and enter the fray.

The Glowering Icon

FIRST STOP, NATURALLY, was the Temple of Zeus, home to the most famous statue in the entire Mediterranean, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. Today at Olympia, all that remains of the temple is a bare limestone platform. Archaeologists have recently raised a single fluted Doric column to its original height of sixty feet; the remains of thirty-three others, hewn from rough conglomerate, lie broken on the lawn like Lego blocks. In antiquity, the columns must have been magnificent and imposing—plastered and painted, supporting an entablature decorated with gilt bronze, red, and blue; inside, the floors were flagstones of black and white marble, with mosaics of Sirens.

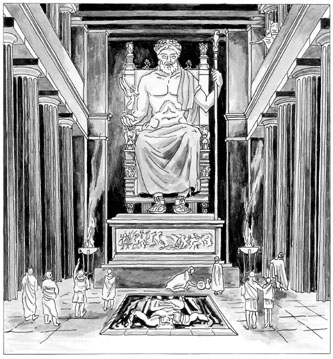

An artist’s re-creation of Phidias’ statue of Zeus, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

An ancient visitor would have listened to his guide recite the temple measurements (250 feet in length, 95 breadth, 68 height, Pausanias noted) before passing through a pair of giant bronze doors, only then to pause blinking in the darkness. Pagan temples were built facing east toward the sunrise, but there were no windows, so it took a few seconds to become accustomed to the gloom. As they pushed forward to the back chamber, however, they suddenly caught their breath: the bearded figure of Olympian Zeus loomed before them, forty feet high, presiding on his throne of cedar, glowering back at them in the flickering torchlight. Although the statue of Zeus has not survived, we know its details from innumerable ancient descriptions. The god’s muscular flesh was carved from ivory, his robes plated in gold. In his right hand he held a scepter gleaming with gems, in his other, outstretched palm the winged statue of Victory. The vast statue was nearly too big for the temple. Zeus’s head almost scraped the ceiling, noted the Greek geographer Strabo—if he wanted to stand, he would tear the roof off. But it was the god’s grave expression, framed by his leonine tresses and flowing beard, that truly humbled the viewer. To the ancients, Zeus represented awesome, invincible power as well as sympathetic humanity. The sculptor Phidias, who created the statue, said that he had been inspired by a description of the god by Homer in The Iliad. Alexander Pope’s translation of the verse conveys the grandeur:

(Zeus) spoke, and awful bends his sable brows,

Shakes his ambrosial curls, and gives the nod:

The stamp of fate and sanction of the God.

High heaven with tremblings the dread signal took,

And all Olympus to the centre shook.

Pausanias himself found it hard to believe his guide’s word that the statue was only forty feet tall: the sheer force of Zeus’s presence made it seem immeasurably larger. Other audience reactions were just as hyperbolic. Beholding the image was a life experience, raved the philosopher Epictetus: No man could die happy who had not seen it. The Roman general Aemilius Paulus was “affected profoundly”—he felt that he had “beheld Zeus in person.” Dio the Golden-Tongued said that the statue made humans forget their daily sorrows; even stray dogs who wandered into the temple were stunned into silence.

“Father and King,” mumbled awestruck worshipers, “Protector of Cities, God of Friendship and Hospitality, Giver of Increase . . .”

Stunning though the image was, the temple was hardly a scene of monastic silence. Greeks treated statues of their gods as if they were alive. During the Olympics, priests dressed Zeus in judges’ robes and were constantly rushing in from the Stadium to announce the results of each event. The workers called the Burnishers were forever massaging the statue with oil drawn from a black marble pool; it trickled through the statue’s interior along minuscule channels created by Phidias to transmit the preservative fluid like arteries in a human body. And the temple floor was crowded with supplicants who stood before Zeus with outstretched arms, their heads barely reaching the god’s knees, arguing their cases out loud—athletes asking to be blessed with victory, villagers praying for assistance with the winter rain, politicians asking for success in diplomacy, soldiers seeking benedictions. Scattered everywhere were gifts and offerings—miniature statues, golden horns of plenty, shields and trophies, even mounds of human hair: Greek teenagers emerging from puberty traditionally left one of their locks to Zeus.

The building had a mezzanine level, so visitors could admire Phidias’ artwork at head height. This also allowed them to whisper their more personal requests into Zeus’s shell-like ear—trying to avoid vertigo as they did so, since they were teetering up as high as a three-story house. The supreme deity took a briskly bureaucratic attitude toward the prayers of mortals, requiring worshipers to fill out small papyrus pledges that stated what gift the god would be given—usually sacrifices or donations of money—if the wish was granted. The pledge would then be affixed with wax to the walls of the temple; the dark interior was covered with these scraps, like a subterranean cave lined with fluttering moths.

Phidias was so famous and beloved—he had also created a giant image of Athena for the Parthenon of Athens—that there was a modest “artist trail” at Olympia for his admirers to follow. The workshop where the maestro had built his statue of Zeus had been preserved for posterity, and Pausanias inspected it at leisure. (Today, the workshop is still in good condition at Olympia. In 1958, German archaeologists found bronze tools, fragments of ivory and glass—evidently chips from a sculpture—and even a black-glazed drinking vessel with the inscription Pheidio eimi, “I belong to Phidias.”) Ancient tourists were then shown a commemorative jar marking the spot struck by a lightning bolt when Phidias had asked Zeus for a sign of his approval, around 420 B.C., of the newly completed statue. True Phidias fans might have rushed back for a closer look at the image. Hidden on one hand was a snatch of graffiti supposedly inscribed by Phidias himself, dedicated to his teenage boyfriend: “Pantarkes is beautiful.”

Celebrity in the ancient world had its dangers, even for artwork. In A.D. 40, the deranged Roman emperor Caligula ordered the statue of Zeus decapitated, and his own head placed on Zeus’s shoulders. Heaven made short work of the blasphemy. When workmen approached the temple, a deafening peal of laughter rang out, nearly shattering their eardrums. The boat sent from Italy to fetch the statue was then struck by lightning. Caligula took the divine hint and left the statue of Zeus alone, but of course nobody in Greece was surprised when, the following year, the emperor was murdered.

Unfortunately, we cannot share the ancients’ awe today. The illustrious statue was finally moved by a Christian emperor to Constantinople in the fourth century A.D., where it perished in a palace fire about a century later.

VISITING ZEUS WAS merely the beginning of a busy afternoon for ancient tourists. Every spare inch of the temple was covered with paintings and friezes illustrating episodes from Greek myth. The statue’s cedar chair was engraved with images of the Amazons, the warrior women of the East. Interior walls were covered with metopes—stone reliefs recounting the Twelve Labors of Hercules. Outside, the temple’s eastern pediment was decorated with a magnificent set of statues depicting a scene from Pelops’ bloody chariot race. The western pediments showed the figures of drunken centaurs trying to carry off women at the wedding festival of the Lapiths. (The two groups of statues, miraculously, survive and are on display at the Olympia museum today, although without the garish colored backdrops that made them stand out in antiquity; the gables behind the statues, archaeologists believe, were bright blue.)

Highlights in the Sacred Grove vicinity included the statue of Nike (Victory) taking flight atop a twenty-five-foot pillar carved by Paionios in 421 B.C.; mythological bric-a-brac in the Temple of Hera, including a Sphinx with a smiling female face; and shields captured from the Persians during the battle of Marathon. Like all ancient tourists, Pausanias was even more excited by actual relics of mythology. In the temple of Hera, he gazed upon the ivory horn of the goat Amalthea, who had suckled the infant god Zeus. Standing in a nearby field was a single charred wooden pillar, a remnant from the palace of the sadistic King Oinomaos, who had been killed in the chariot race with Pelops; after the king’s demise, it had been blasted to smithereens by a lightning bolt from the gods. Pausanias was disappointed on his visit that the enormous shoulder blade of the hero Pelops himself, which had been fished from the waters near Troy by fishermen, had not survived for his admiration. Whalebones and dinosaur fossils were often put on display by the Greeks as physical evidence of heroes, giants, and Titans. (“I suppose the bone moldered away with age,” Pausanias writes resignedly in his guidebook, “from the corrosive action of the salt water in which it had been sunk so long.”)

The Lure of the Water

IN THE CRUSHING heat of the afternoon, visitors must have cast longing eyes toward the western edge of the sanctuary, where they knew a large swimming pool existed. Olympia was unique in Greece for having such an asset—about twenty-four meters long by sixteen meters wide, and around 1.6 meters (five feet) deep, roughly half the size of an “Olympic pool” today. But it was used for recreation rather than competitions, and probably open only to VIPs and athletes. It is strange that, among a people who even held eating races at dinner, swimming was one of the only pursuits that was not elevated to a competition, except in one small, provincial city called Hermione.

To the Greeks, who grew up surrounded by rivers, lakes, and the pellucid waters of the Aegean, swimming was as natural as walking, and unworthy of contests. To be unable to swim—at least among the free male population—was as much a sign of an uneducated person, or barbarian, as being illiterate. From vase paintings, it appears that their favorite stroke was freestyle, although they were familiar with the sidestroke, backstroke, and breaststroke, and would dive from sheer cliffs. City elders certainly recognized the practical value of swimming for maritime powers. At the great naval battle of Salamis, the Greeks suffered remarkably few casualties because their sailors could all escape porpoiselike to shore, while the unfortunate Persians sank like stones. Tales abound of Greek sailors dodging arrows by swimming underwater or using divers to destroy underwater traps. Rowing, however, and various boat races became very popular at municipal games. In Athens, regattas were held in boats with crews of up to eight men—and even races of full-blown military ships. Triremes with triple banks of oars would compete off Cape Sounion, where a magnificent Temple of Poseidon stood sentinel, and priests would sacrifice giant tuna, pouring their black blood on the altar.