XVIII.

Last Rites

And then the strict judges, fulfilling the ancient

ordinances of Hercules, set the

gray ornament of olive upon the victor’s hair.

—PINDAR, OLYMPIAN ODE

THE LAST DAY of the festival dawned on the wreckage of another long night of partying, with revelers curled up in corners like corpses and dogs picking over the putrefying garbage. Hungover wrestlers, boxers, and pankratiasts who rose to give thanks at the altar of Hercules were joined by another victor from the day before—winner of a peculiar ancient contest called hoplitodromia, or race-in-armor. The last sporting event of the Games, named after the Greek foot soldiers called hoplites, it was taken rather less seriously than regal contact sports. The contestants, who had not been required to go through the rigorous Olympic training, donned ceremonial bronze armor, then clunked up and down two laps of the Stadium. The race was famously clumsy, with runners banging into one another, dropping their shields, losing their helmets, and tripping. Whether or not the scene was regarded by Greeks as laughable, the race certainly inspired gently mocking references: In Aristophanes’ comedy The Birds, a character likens the Chorus figures, who are dressed up in feathered costumes, to the runners-in-armor.

Now, on day five, dignity would return in Olympia—in the form of prestigious award ceremonies.

In the Temple of Zeus, olive wreaths were laid out on an ivory and gold table. These crowns were almost mythological items: In a traditional ritual, they had been cut from Zeus’s sacred tree by a young boy, both of whose parents were alive, using a golden sickle. (Spectators at Olympia could admire the tree itself, which had been planted by Hercules, protected by a fence on the west side of the Sacred Grove.) Until this moment, champions had been identified among the crowd by victory ribbons on their arms and the pine branches they carried. Now, bathed and groomed, they entered the sanctum sanctorum of Olympia, where they were announced before Zeus and then had the olive wreaths placed on their heads. Reemerging, they were carried on the shoulders of their friends around the grove as musicians played and flower petals rained down.

To the Greeks, this was as close to deification as any mortal could come—and the glory could compound over generations. In 448 B.C., according to chronicles, the boxer Diagoras of Rhodes, Olympic victor sixteen years earlier, saw his two sons both win wreaths for the pankration and boxing. As the young men hoisted their father on their shoulders and put each of their laurel wreaths on his head, a member of the crowd shouted out, “You might as well go up to heaven, Diagoras; there’s nothing greater for you to achieve on earth.” And with a happy smile, Diagoras died on the spot.

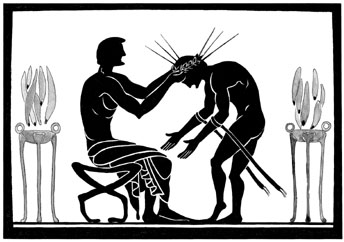

A champion accepts his wreath from a judge. Hanging from his arms are victory fillets, or ribbons. (From an Athenian amphora, c. 525 B.C.)

After the wreaths had been presented, the champions would be escorted to a private feast hosted by the judges. It was held in a venerable banquet hall in the Prytaneion, the administrative center of the Games, whose every wall oozed tradition: In one wing, the eternal flame was kept burning; in another lay the archives of the Olympic Games, dating back to 776 B.C.; and all over the walls were fantastic relics and memorabilia from famous events, the discuses and javelins and gloves of heroes. The banquet was fit for demigods, and past victors were welcome to attend. One imagines the new victors sitting in such glorious company with distant eyes, thinking of their futures. Modesty was never an ancient virtue, and they eagerly gloated about their prospects.

The Road to Riches

AH, THE SWEET taste of immortality. An Olympic champion knew his name would be passed on from generation to generation, preserved in records throughout the known world, far better remembered than the names of kings or presidents today. There would be a victory statue to commission in Olympia—perhaps an ego-boosting choral song. And there were material rewards. It’s true that the only official prize was the olive wreath, but when Pindar wrote that an Olympic champion was guaranteed “sweet smooth sailing for the rest of his life,” he was not exaggerating. Financially speaking, a victor was a made man. He would journey back to his home city in a triumphant parade, entering the gates in a four-horse chariot, where an adoring populace would shower him with gifts—cash rewards, a lifetime supply of oil, invitations to state banquets, front-row seats at the amphitheater, tax immunity, villas, pensions. In 416 B.C., the ecstatic city elders of Agrigentum in Sicily gave one Olympic victor a celebration parade of three hundred chariots, each led by four white horses. Proud cities engraved athletes’ names in gilded letters in temples, or stamped their profiles on coins. For years to come, the victory would be a money spinner, since champions could rack up fortunes simply by making appearances at provincial sporting events. In the second century A.D., a small city in Asia Minor paid an Olympic boxer a staggering thirty thousand drachmas for a cameo bout (around one hundred times a Roman army soldier’s annual pay); another offered fifty pounds of silver to a celebrity pankratiast just to show his face at their festival.

But why settle for mere money? Olympia was the perfect springboard for a career change, and a champion could easily become a judge, a priest, an ambassador. After his chariot win in 416 B.C., Alcibiades landed a plum military command in the invasion of Sicily. The great Theagenes of Thasos became a politician, styling himself as the “Son of Hercules”; in the Roman era, one Marcus Aurelius Asclepiades became a senator in Athens. Other victors were even hired as the emperor’s personal trainer.

Just as a victor’s fortunes soared, the prospects for the defeated were grim: They woke up on day five to a miserable horizon of failure. Good sportsmanship was thin on the ground in ancient Greece. There were no second prizes, no handshakes for a battle well fought. While the champions were being feted by the happy crowds, other, humiliated athletes slipped away from Olympia quietly, “skulking home to their mothers, traveling down back roads, hiding from their enemies, bitten by their calamity,” wrote Pindar. Unlike the victors, their homecoming would be greeted by “no sweet laughter creating delight,” but shame, embarrassment, and public mockery. As the Oxford Classical Dictionary laconically notes of these defeated athletes, “the incidence of failure-induced depression and mental illness was likely to be very high.”

Perhaps the ultimate sore loser was the boxer Kleomedes, who, disqualified from his event in 492 B.C., “went out of his mind with grief.” On his return to his home island of Astypalaea, he attacked a school building, pulling down a pillar and collapsing the roof on sixty boys inside. The angry townspeople came after Kleomedes with rocks, but he hid in a wooden box in the sanctuary of Athena. When it was smashed open, he had disappeared. In a surprise twist of events, the Astypalaeans consulted the oracle of Delphi, which told them that the deranged boxer was “no longer mortal.” “From that day onwards,” Pausanias observes, “the Astypalians worshipped Kleomedes as a hero.”

The After-Party

THE CHAMPIONS MAY have clattered off in their gilded chariots, but for rank-and-file sports fans, as ever, getting home would not be so easy. Like the end of any mass spectator event today, anarchy descended on the site of Olympia as the hordes clogged the roads and haggled over the remaining transport. And yet, some willingly remained—the party animals who refused to let the revelry die. Apollonius of Tyana took up residence for forty days and forty nights, until he and his entourage ran out of funds to move on. His sidekicks were ashamed, but Apollonius simply strode into the Temple of Zeus and asked for one thousand drachmas, “if you do not think Zeus would be too annoyed.” The priests generously replied that the only thing that would annoy the god would be if Apollonius did not take even more cash than he’d requested. One has the odd feeling they were glad to be rid of him.

The Cynic philosopher Peregrinus chose the postfestival period, with its captive audience, as the ideal time to publicly immolate himself in A.D. 165. He had announced his intention during the Games, saying that he was inspired by tales of the Indian Brahmans and their contempt for worldly values. The caustic Lucian mocked Peregrinus as a “publicity-mad fool”—“I wouldn’t put it past him to jump out again half-cooked,” another critic snickered—but still joined the curious crowd that got up at midnight and walked two miles to witness the moonlit suicide. As the old philosopher approached the pyre in his mendicant’s rags, some observers were awestruck, others derisive of the grandstanding, still others drunkenly chanted, “Get on with it!” Looking pale, Peregrinus tossed incense into the flames, cried out, “Gods of my mother! Gods of my fire! Be gracious with me!” and leapt into the flames.

Lucian remained unimpressed—“I couldn’t keep from guffawing,” he says, nearly provoking a brawl with the philosopher’s supporters—but Peregrinus had gained a place in Olympic history. Rumors soon circulated that the philosopher’s ghost could be seen strolling the sanctuary in white robes and an ivy crown, smiling beatifically.

AS THE LAST stragglers left, laborers from Elis worked their way around the deserted site, antlike and determined, raking the Stadium, washing down the temples, using the wells they had dug before the Games as garbage pits. The rest of the debris, including the wooden frames of the vendors’ booths and spectators’ barracks, were burned.

The smoke from these great bonfires mingled with the last parched breaths of summer. We can imagine a stream of ash billowing across the ravines of Arcadia, dusting the brittle olive groves and rocky fields where goatherds contemplated their flocks, floating over the temples and the crags, the bone-white beaches and the abysses of blue, to the dark granite pillar of Mount Olympus in northern Greece, where the gods, in their palaces, were well pleased.

Champions and spectators were home in their distant hearths, but the clockwork of the seasons, of festivals and generations, continued on its course.

The organizers of Elis drew a deep breath—then began planning the next Games.