I invented this law in Neubrandenburg, Germany, in the late summer of 1990.

In an effort to improve my barely existing German-language skills before spending a year in Berlin as a guest of the Wissenschaftskolleg, I hit on the idea of finding work on a farm rather than attending daily classes with pimply teenagers at a Goethe Institut center. Since the Wall had come down only a year earlier, I wondered whether I might be able to find a six-week summer job on a collective farm (landwirtschaftliche Produktionsgenossenschaft, or LPG), recently styled “cooperative,” in eastern Germany. A friend at the Wissenschaftskolleg had, it turned out, a close relative whose brother-in-law was the head of a collective farm in the tiny village of Pletz. Though wary, the brother-in-law was willing to provide room and board in return for work and a handsome weekly rent.

As a plan for improving my German by the sink-or-swim method, it was perfect; as a plan for a pleasant and edifying farm visit, it was a nightmare. The villagers and, above all, my host were suspicious of my aims. Was I aiming to pore over the accounts of the collective farm and uncover “irregularities”? Was I an advance party for Dutch farmers, who were scouting the area for land to rent in the aftermath of the socialist bloc’s collapse?

The collective farm at Pletz was a spectacular example of that collapse. Its specialization was growing “starch potatoes.” They were no good for pommes frites, though pigs might eat them in a pinch; their intended use, when refined, was to provide the starch base for Eastern European cosmetics. Never had a market flatlined as quickly as the market for socialist bloc cosmetics the day after the Wall was breached. Mountain after mountain of starch potatoes lay rotting beside the rail sidings in the summer sun.

Besides wondering whether utter penury lay ahead for them and what role I might have in it, for my hosts there was the more immediate question of my frail comprehension of German and the danger it posed for their small farm. Would I let the pigs out the wrong gate and into a neighbor’s field? Would I give the geese the feed intended for the bulls? Would I remember always to lock the door when I was working in the barn in case the Gypsies came? I had, it is true, given them more than ample cause for alarm in the first week, and they had taken to shouting at me in the vain hope we all seem to have that yelling will somehow overcome any language barrier. They managed to maintain a veneer of politeness, but the glances they exchanged at supper told me their patience was wearing thin. The aura of suspicion under which I labored, not to mention my manifest incompetence and incomprehension, was in turn getting on my nerves.

I decided, for my sanity as well as for theirs, to spend one day a week in the nearby town of Neubrandenburg. Getting there was not simple. The train didn’t stop at Pletz unless you put up a flag along the tracks to indicate that a passenger was waiting and, on the way back, told the conductor that you wanted to get off at Pletz, in which case he would stop specially in the middle of the fields to let you out. Once in the town I wandered the streets, frequented cafes and bars, pretended to read German newspapers (surreptitiously consulting my little dictionary), and tried not to stick out.

The once-a-day train back from Neubrandenburg that could be made to stop at Pletz left at around ten at night. Lest I miss it and have to spend the night as a vagrant in this strange city, I made sure I was at the station at least half an hour early. Every week for six or seven weeks the same intriguing scene was played out in front of the railroad station, giving me ample time to ponder it both as observer and as participant. The idea of “anarchist calisthenics” was conceived in the course of what an anthropologist would call my participant observation.

Outside the station was a major, for Neubrandenburg at any rate, intersection. During the day there was a fairly brisk traffic of pedestrians, cars, and trucks, and a set of traffic lights to regulate it. Later in the evening, however, the vehicle traffic virtually ceased while the pedestrian traffic, if anything, swelled to take advantage of the cooler evening breeze. Regularly between 9:00 and 10:00 p.m. there would be fifty or sixty pedestrians, not a few of them tipsy, who would cross the intersection. The lights were timed, I suppose, for vehicle traffic at midday and not adjusted for the heavy evening foot traffic. Again and again, fifty or sixty people waited patiently at the corner for the light to change in their favor: four minutes, five minutes, perhaps longer. It seemed an eternity. The landscape of Neubrandenburg, on the Mecklenburg Plain, is flat as a pancake. Peering in each direction from the intersection, then, one could see a mile of so of roadway, with, typically, no traffic at all. Very occasionally a single, small Trabant made its slow, smoky way to the intersection.

Twice, perhaps, in the course of roughly five hours of my observing this scene did a pedestrian cross against the light, and then always to a chorus of scolding tongues and fingers wagging in disapproval. I too became part of the scene. If I had mangled my last exchange in German, sapping my confidence, I stood there with the rest for as long as it took for the light to change, afraid to brave the glares that awaited me if I crossed. If, more rarely, my last exchange in German had gone well and my confidence was high, I would cross against the light, thinking, to buck up my courage, that it was stupid to obey a minor law that, in this case, was so contrary to reason.

It surprised me how much I had to screw up my courage merely to cross a street against general disapproval. How little my rational convictions seemed to weigh against the pressure of their scolding. Striding out boldly into the intersection with apparent conviction made a more striking impression, perhaps, but it required more courage than I could normally muster.

As a way of justifying my conduct to myself, I began to rehearse a little discourse that I imagined delivering in perfect German. It went something like this. “You know, you and especially your grandparents could have used more of a spirit of lawbreaking. One day you will be called on to break a big law in the name of justice and rationality. Everything will depend on it. You have to be ready. How are you going to prepare for that day when it really matters? You have to stay ‘in shape’ so that when the big day comes you will be ready. What you need is ‘anarchist calisthenics.’ Every day or so break some trivial law that makes no sense, even if it’s only jaywalking. Use your own head to judge whether a law is just or reasonable. That way, you’ll keep trim; and when the big day comes, you’ll be ready.”

Judging when it makes sense to break a law requires careful thought, even in the relatively innocuous case of jaywalking. I was reminded of this when I visited a retired Dutch scholar whose work I had long admired. When I went to see him, he was an avowed Maoist and defender of the Cultural Revolution, and something of an incendiary in Dutch academic politics. He invited me to lunch at a Chinese restaurant near his apartment in the small town of Wageningen. We came to an intersection, and the light was against us. Now, Wageningen, like Neubrandenburg, is perfectly flat, and one can see for miles in all directions. There was absolutely nothing coming. Without thinking, I stepped into the street, and as I did so, Dr. Wertheim said, “James, you must wait.” I protested weakly while regaining the curb, “But Dr. Wertheim, nothing is coming.” “James,” he replied instantly, “It would be a bad example for the children.” I was both chastened and instructed. Here was a Maoist incendiary with, nevertheless, a fine-tuned, dare I say Dutch, sense of civic responsibility, while I was the Yankee cowboy heedless of the effects of my act on my fellow citizens. Now when I jaywalk I look around to see that there are no children who might be endangered by my bad example.

Toward the very end of my farm stay in Neubrandenburg, there was a more public event that raised the issue of lawbreaking in a more striking way. A little item in the local newspaper informed me that anarchists from West Germany (the country was still nearly a month from formal reunification, or Einheit) had been hauling a huge papier-mâché statue from city square to city square in East Germany on the back of a flatbed truck. It was the silhouette of a running man carved into a block of granite. It was called Monument to the Unknown Deserters of Both World Wars (Denkmal an die unbekannten Deserteure der beiden Weltkriege) and bore the legend, “This is for the man who refused to kill his fellow man.”

It struck me as a magnificent anarchist gesture, this contrarian play on the well-nigh universal theme of the Unknown Soldier: the obscure, “every-infantryman” who fell honorably in battle for his nation’s objectives. Even in Germany, even in very recently ex–East Germany (celebrated as “The First Socialist State on German Soil”), this gesture was, however, distinctly unwelcome. For no matter how thoroughly progressive Germans may have repudiated the aims of Nazi Germany, they still bore an ungrudging admiration for the loyalty and sacrifice of its devoted soldiers. The Good Soldier Švejk, the Czech antihero who would rather have his sausage and beer near a warm fire than fight for his country, may have been a model of popular resistance to war for Bertolt Brecht, but for the city fathers of East Germany’s twilight year, this papier-mâché mockery was no laughing matter. It came to rest in each town square only so long as it took for the authorities to assemble and banish it. Thus began a merry chase: from Magdeburg to Potsdam to East Berlin to Bitterfeld to Halle to Leipzig to Weimar to Karl-Marx-Stadt (Chemnitz) to Neubrandenburg to Rostock, ending finally back in the then federal capital, Bonn. The city-to-city scamper and the inevitable publicity it provoked may have been precisely what its originators had in mind.

The stunt, aided by the heady atmosphere in the two years following the breach in the Berlin Wall, was contagious. Soon, progressives and anarchists throughout Germany had created dozens of their own municipal monuments to desertion. It was no small thing that an act traditionally associated with cowards and traitors was suddenly held up as honorable and perhaps even worthy of emulation. Small wonder that Germany, which surely has paid a very high price for patriotism in the service of inhuman objectives, would have been among the first to question publicly the value of obedience and to place monuments to deserters in public squares otherwise consecrated to Martin Luther, Frederick the Great, Bismarck, Goethe, and Schiller.

A monument to desertion poses something of a conceptual and aesthetic challenge. A few of the monuments erected to deserters throughout Germany were of lasting artistic value, and one, by Hannah Stuetz Menzel, at Ulm, at least managed to suggest the contagion that such high-stakes acts of disobedience can potentially inspire (fig. 1.1).

Acts of disobedience are of interest to us when they are exemplary, and especially when, as examples, they set off a chain reaction, prompting others to emulate them. Then we are in the presence less of an individual act of cowardice or conscience—perhaps both—than of a social phenomenon that can have massive political effects. Multiplied many thousandfold, such petty acts of refusal may, in the end, make an utter shambles of the plans dreamed up by generals and heads of state. Such petty acts of insubordination typically make no headlines. But just as millions of anthozoan polyps create, willy-nilly, a coral reef, so do thousands upon thousands of acts of insubordination and evasion create an economic or political barrier reef of their own. A double conspiracy of silence shrouds these acts in anonymity. The perpetrators rarely seek to call attention to themselves; their safety lies in their invisibility. The officials, for their part, are reluctant to call attention to rising levels of disobedience; to do so would risk encouraging others and call attention to their fragile moral sway. The result is an oddly complicitous silence that all but expunges such forms of insubordination from the historical record.

Figure 1.1. Memorial for the Unknown Deserter, by Mehmet Aksoy, Potsdam. Photograph courtesy of Volker Moerbitz, Monterey Institute of International Studies

And yet, such acts of what I have elsewhere called “everyday forms of resistance” have had enormous, often decisive, effects on the regimes, states, and armies at which they are implicitly directed. The defeat of the Confederate states in America’s great Civil War can almost certainly be attributed to a vast aggregation of acts of desertion and insubordination. In the fall of 1862, little more than a year after the war began, there were widespread crop failures in the South. Soldiers, particularly those from the non-slave-holding backcountry, were getting letters from famished families urging them to return home. Many thousands did, often as whole units, taking their arms with them. Having returned to the hills, most of them actively resisted conscription for the duration of the war.

Later, following the decisive Union victory at Missionary Ridge in the winter of 1863, the writing was on the wall and the Confederate forces experienced a veritable hemorrhage of desertions, again, especially from small-holding, up-country recruits who had no direct interest in the preservation of slavery, especially when it seemed likely to cost them their own lives. Their attitude was summed up in a popular slogan of the time in the Confederacy that the war was “A rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight,” a slogan only reinforced by the fact that rich planters with more than twenty slaves could keep one son at home, presumably to ensure labor discipline. All told, something like a quarter of a million eligible draft-age men deserted or evaded service altogether. To this blow, absorbed by a Confederacy already overmatched in manpower, must be added the substantial numbers of slaves, especially from the border states, who ran to the Union lines, many of whom then enlisted in the Union forces. Last, it seems that the remaining slave population, cheered by Union advances and reluctant to exhaust themselves to increase war production, dragged their feet whenever possible and frequently absconded as well to refuges such as the Great Dismal Swamp, along the Virginia–North Carolina border, where they could not be easily tracked. Thousands upon thousands of acts of desertion, shirking, and absconding, intended to be unobtrusive and to escape detection, amplified the manpower and industrial advantage of the Union forces and may well have been decisive in the Confederacy’s ultimate defeat.

Napoleon’s wars of conquest were ultimately crippled by comparable waves of disobedience. While it is claimed that Napoleon’s invading soldiers brought the French Revolution to the rest of Europe in their knapsacks, it is no exaggeration to assert that the limits of these conquests were sharply etched by the disobedience of the men expected to shoulder those knapsacks. From 1794 to 1796 under the Republic, and then again from 1812 under the Napoleonic empire, the difficulty of scouring the countryside for conscripts was crippling. Families, villages, local officials, and whole cantons conspired to welcome back recruits who had fled and to conceal those who had evaded conscription altogether, some by severing one or more fingers of their right hand. The rates of draft evasion and desertion were something of a referendum on the popularity of the regime and, given their strategic importance of these “voters-with-their-feet” to the needs of Napoleon’s quartermasters, the referendum was conclusive. While the citizens of the First Republic and of Napoleon’s empire may have warmly embraced the promise of universal citizenship, they were less enamored of its logical twin, universal conscription.

Stepping back a moment, it’s worth noticing something particular about these acts: they are virtually all anonymous, they do not shout their name. In fact, their unobtrusiveness contributed to their effectiveness. Desertion is quite different from an open mutiny that directly challenges military commanders. It makes no public claims, it issues no manifestos; it is exit rather than voice. And yet, once the extent of desertion becomes known, it constrains the ambitions of commanders, who know they may not be able to count on their conscripts. During the unpopular U.S. war in Vietnam, the reported “fragging” (throwing of a fragmentation grenade) of those officers who repeatedly exposed their men to deadly patrols was a far more dramatic and violent but nevertheless still anonymous act, meant to lessen the deadly risks of war for conscripts. One can well imagine how reports of fragging, whether true or not, might make officers hesitate to volunteer themselves and their men for dangerous missions. To my knowledge, no study has ever looked into the actual incidence of fragging, let alone the effects it may have had on the conduct and termination of the war. The complicity of silence is, in this case as well, reciprocal.

Quiet, anonymous, and often complicitous, lawbreaking and disobedience may well be the historically preferred mode of political action for peasant and subaltern classes, for whom open defiance is too dangerous. For the two centuries from roughly 1650 to 1850, poaching (of wood, game, fish, kindling, fodder) from Crown or private lands was the most popular crime in England. By “popular” I mean both the most frequent and the most heartily approved of by commoners. Since the rural population had never accepted the claim of the Crown or the nobility to “the free gifts of nature” in forests, streams, and open lands (heath, moor, open pasture), they violated those property rights en masse repeatedly, enough to make the elite claim to property rights in many areas a dead letter. And yet, this vast conflict over property rights was conducted surreptitiously from below with virtually no public declaration of war. It is as if villagers had managed, de facto, defiantly to exercise their presumed right to such lands without ever making a formal claim. It was often remarked that the local complicity was such that gamekeepers could rarely find any villager who would serve as state’s witness.

In the historical struggle over property rights, the antagonists on either side of the barricades have used the weapons that most suited them. Elites, controlling the lawmaking machinery of the state, have deployed bills of enclosure, paper titles, and freehold tenure, not to mention the police, gamekeepers, forest guards, the courts, and the gibbet to establish and defend their property rights. Peasants and subaltern groups, having no access to such heavy weaponry, have instead relied on techniques such as poaching, pilfering, and squatting to contest those claims and assert their own. Unobtrusive and anonymous, like desertion, these “weapons of the weak” stand in sharp contrast to open public challenges that aim at the same objective. Thus, desertion is a lower-risk alternative to mutiny, squatting a lower-risk alternative to a land invasion, poaching a lower-risk alternative to the open assertion of rights to timber, game, or fish. For most of the world’s population today, and most assuredly for subaltern classes historically, such techniques have represented the only quotidian form of politics available. When they have failed, they have given way to more desperate, open conflicts such as riots, rebellions, and insurgency. These bids for power irrupt suddenly onto the official record, leaving traces in the archives beloved of historians and sociologists who, having documents to batten on, assign them a pride of place all out of proportion to the role they would occupy in a more comprehensive account of class struggle. Quiet, unassuming, quotidian insubordination, because it usually flies below the archival radar, waves no banners, has no officeholders, writes no manifestos, and has no permanent organization, escapes notice. And that’s just what the practitioners of these forms of subaltern politics have in mind: to escape notice. You could say that, historically, the goal of peasants and subaltern classes has been to stay out of the archives. When they do make an appearance, you can be pretty sure that something has gone terribly wrong.

If we were to look at the great bandwidth of subaltern politics all the way from small acts of anonymous defiance to massive popular rebellions, we would find that outbreaks of riskier open confrontation are normally preceded by an increase in the tempo of anonymous threats and acts of violence: threatening letters, arson and threats of arson, cattle maiming, sabotage and nighttime machine breaking, and so on. Local elites and officials historically knew these as the likely precursors of open rebellion; and they were intended to be read as such by those who engaged in them. Both the frequency of insubordination and its “threat level” (pace the Office of Homeland Security) were understood by contemporary elites as early warning signs of desperation and political unrest. One of the first op-eds of the young Karl Marx noted in great detail the correlation between, on the one hand, unemployment and declining wages among factory workers in the Rhineland, and on the other, the frequency of prosecution for the theft of firewood from private lands.

The sort of lawbreaking going on here is, I think, a special subspecies of collective action. It is not often recognized as such, in large part because it makes no open claims of this kind and because it is almost always self-serving at the same time. Who is to say whether the poaching hunter is more interested in a warm fire and rabbit stew than in contesting the claim of the aristocracy to the wood and the game he has just taken? It is most certainly not in his interest to help the historian with a public account of his motives. The success of his claim to wood and game lies in keeping his acts and motives shrouded. And yet, the long-run success of this lawbreaking depends on the complicity of his friends and neighbors who may believe in his and their right to forest products and may themselves poach and, in any case, will not bear witness against him or turn him in to the authorities.

One need not have an actual conspiracy to achieve the practical effects of a conspiracy. More regimes have been brought, piecemeal, to their knees by what was once called “Irish democracy,” the silent, dogged resistance, withdrawal, and truculence of millions of ordinary people, than by revolutionary vanguards or rioting mobs.

To see how tacit coordination and lawbreaking can mimic the effects of collective action without its inconveniences and dangers, we might consider the enforcement of speed limits. Let’s imagine that the speed limit for cars is 55 miles per hour. Chances are that the traffic police will not be much inclined to prosecute drivers going 56, 57, 58 … even 60 mph, even though it is technically a violation. This “ceded space of disobedience” is, as it were, seized and becomes occupied territory, and soon much of the traffic is moving along at roughly 60 mph. What about 61, 62, 63 mph? Drivers going just a mile or two above the de facto limit are, they reason, fairly safe. Soon the speeds from, say, 60 to 65mph bid fair to become conquered territory as well. All of the drivers, then, going about 65 mph come absolutely to depend for their relative immunity from prosecution on being surrounded by a veritable capsule of cars traveling at roughly the same speed. There is something like a contagion effect that arises from observation and tacit coordination taking place here, although there is no “Central Committee of Drivers” meeting and plotting massive acts of civil disobedience. At some point, of course, the traffic police do intervene to issue fines and make arrests, and the pattern of their intervention sets terms of calculation that drivers must now consider when deciding how fast to drive. The pressure at the upper end of the tolerated speed, however, is always being tested by drivers in a hurry, and if, for whatever reason, enforcement lapses, the tolerated speed will expand to fill it. As with any analogy, this one must not be pushed too far. Exceeding the speed limit is largely a matter of convenience, not a matter of rights and grievances, and the dangers to speeders from the police are comparatively trivial. (If, on the contrary, we had a 55-mph speed limit and, say, only three traffic police for the whole nation, who summarily executed five or six speeders and strung them up along the interstate highways, the dynamic I have described would screech to a halt!)

I’ve noticed a similar pattern in the way that what begin as “shortcuts” in walking paths often end up becoming paved walkways. Imagine a pattern of daily walking trajectories that, were they confined to paved sidewalks, would oblige people to negotiate the two sides of a right triangle rather than striking out along the (unpaved) hypotenuse. Chances are, a few would venture the shortcut and, if not thwarted, establish a route that others would be tempted to take merely to save time. If the shortcut is heavily trafficked and the groundskeepers relatively tolerant, the shortcut may well, over time, come to be paved. Tacit coordination again. Of course, virtually all of the lanes in older cities that grew from smaller settlements were created in precisely this way; they were the formalization of daily pedestrian and cart tracks, from the well to the market, from the church or school to the artisan quarter—a good example of the principle attributed to Chuang Tzu, “We make the path by walking.”

The movement from practice to custom to rights inscribed in law is an accepted pattern in both common and positive law. In the Anglo-American tradition, it is represented by the law of adverse possession, whereby a pattern of trespass or seizure of property, repeated continuously for a certain number of years, can be used to claim a right, which would then be legally protected. In France, a practice of trespass that could be shown to be of long standing would qualify as a custom and, once proved, would establish a right in law.

Under authoritarian rule it seems patently obvious that subjects who have no elected representatives to champion their cause and who are denied the usual means of public protest (demonstrations, strikes, organized social movement, dissident media) would have no other recourse than foot-dragging, sabotage, poaching, theft, and, ultimately, revolt. Surely the institutions of representative democracy and the freedoms of expression and assembly afforded modern citizens make such forms of dissent obsolete. After all, the core purpose of representative democracy is precisely to allow democratic majorities to realize their claims, however ambitious, in a thoroughly institutionalized fashion.

It is a cruel irony that this great promise of democracy is rarely realized in practice. Most of the great political reforms of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries have been accompanied by massive episodes of civil disobedience, riot, lawbreaking, the disruption of public order, and, at the limit, civil war. Such tumult not only accompanied dramatic political changes but was often absolutely instrumental in bringing them about. Representative institutions and elections by themselves, sadly, seem rarely to bring about major changes in the absence of the force majeure afforded by, say, an economic depression or international war. Owing to the concentration of property and wealth in liberal democracies and the privileged access to media, culture, and political influence these positional advantages afford the richest stratum, it is little wonder that, as Gramsci noted, giving the working class the vote did not translate into radical political change.1 Ordinary parliamentary politics is noted more for its immobility than for facilitating major reforms.

We are obliged; if this assessment is broadly true, to confront the paradox of the contribution of lawbreaking and disruption to democratic political change. Taking the twentieth-century United States as a case in point, we can identify two major policy reform periods, the Great Depression of the 1930s and the civil rights movement of the 1960s. What is most striking about each, from this perspective, is the vital role massive disruption and threats to public order played in the process of reform.

The great policy shifts represented by the institution of unemployment compensation, massive public works projects, social security aid, and the Agricultural Adjustment Act were, to be sure, abetted by the emergency of the world depression. But the way in which the economic emergency made its political weight felt was not through statistics on income and unemployment but through rampant strikes, looting, rent boycotts, quasi-violent sieges of relief offices, and riots that put what my mother would have called “the fear of God” in business and political elites. They were thoroughly alarmed at what seemed at the time to be potentially revolutionary ferment. The ferment in question was, in the first instance, not institutionalized. That is to say, it was not initially shaped by political parties, trade unions, or recognizable social movements. It represented no coherent policy agenda. Instead it was genuinely unstructured, chaotic, and full of menace to the established order. For this very reason, there was no one to bargain with, no one to credibly offer peace in return for policy changes. The menace was directly proportional to its lack of institutionalization. One could bargain with a trade union or a progressive reform movement, institutions that were geared into the institutional machinery. A strike was one thing, a wildcat strike was another: even the union bosses couldn’t call off a wildcat strike. A demonstration, even a massive one, with leaders was one thing, a rioting mob was another. There were no coherent demands, no one to talk to.

The ultimate source of the massive spontaneous militancy and disruption that threatened public order lay in the radical increase in unemployment and the collapse of wage rates for those lucky enough still to be employed. The normal conditions that sustained routine politics suddenly evaporated. Neither the routines of governance nor the routines of institutionalized opposition and representation made much sense. At the individual level, the deroutinization took the form of vagrancy, crime, and vandalism. Collectively, it took the form of spontaneous defiance in riots, factory occupations, violent strikes, and tumultuous demonstrations. What made the rush of reforms possible were the social forces unleashed by the Depression, which seemed beyond the ability of political elites, property owners, and, it should be noted, trade unions and left-wing parties to master. The hand of the elites was forced.

An astute colleague of mine once observed that liberal democracies in the West were generally run for the benefit of the top, say, 20 percent of the wealth and income distribution. The trick, he added, to keeping this scheme running smoothly has been to convince, especially at election time, the next 30 to 35 percent of the income distribution to fear the poorest half more than they envy the richest 20 percent. The relative success of this scheme can be judged by the persistence of income inequality—and its recent sharpening—over more than a half century. The times when this scheme comes undone are in crisis situations when popular anger overflows its normal channels and threatens the very parameters within which routine politics operates. The brutal fact of routine, institutionalized liberal democratic politics is that the interests of the poor are largely ignored until and unless a sudden and dire crisis catapults the poor into the streets. As Martin Luther King, Jr., noted, “a riot is the language of the unheard.” Large-scale disruption, riot, and spontaneous defiance have always been the most potent political recourse of the poor. Such activity is not without structure. It is structured by informal, self-organized, and transient networks of neighborhood, work, and family that lie outside the formal institutions of politics. This is structure alright, just not the kind amenable to institutionalized politics.

Perhaps the greatest failure of liberal democracies is their historical failure to successfully protect the vital economic and security interests of their less advantaged citizens through their institutions. The fact that democratic progress and renewal appear instead to depend vitally on major episodes of extra-institutional disorder is massively in contradiction to the promise of democracy as the institutionalization of peaceful change. And it is just as surely a failure of democratic political theory that it has not come to grips with the central role of crisis and institutional failure in those major episodes of social and political reform when the political system is relegitimated.

It would be wrong and, in fact, dangerous to claim that such large-scale provocations always or even generally lead to major structural reform. They may instead lead to growing repression, the restriction of civil rights, and, in extreme cases, the overthrow of representative democracy. Nevertheless, it is undeniable that most episodes of major reform have not been initiated without major disorders and the rush of elites to contain and normalize them. One may legitimately prefer the more “decorous” forms of rallies and marches that are committed to nonviolence and seek the moral high ground by appealing to law and democratic rights. Such preferences aside, structural reform has rarely been initiated by decorous and peaceful claims.

The job of trade unions, parties, and even radical social movements is precisely to institutionalize unruly protest and anger. Their function is, one might say, to try to translate anger, frustration, and pain into a coherent political program that can be the basis of policy making and legislation. They are the transmission belt between an unruly public and rule-making elites. The implicit assumption is that if they do their jobs well, not only will they be able to fashion political demands that are, in principle, digestible by legislative institutions, they will, in the process, discipline and regain control of the tumultuous crowds by plausibly representing their interests, or most of them, to the policy makers. Those policy makers negotiate with such “institutions of translation” on the premise that they command the allegiance of and hence can control the constituencies they purport to represent. In this respect, it is no exaggeration to say that organized interests of this kind are parasitic on the spontaneous defiance of those whose interests they presume to represent. It is that defiance that is, at such moments, the source of what influence they have as governing elites strive to contain and channel insurgent masses back into the run of normal politics.

Another paradox: at such moments, organized progressive interests achieve a level of visibility and influence on the basis of defiance that they neither incited nor controlled, and they achieve that influence on the presumption they will then be able to discipline enough of that insurgent mass to reclaim it for politics as usual. If they are successful, of course, the paradox deepens, since as the disruption on which they rose to influence subsides, so does their capacity to affect policy.

The civil rights movement in the 1960s and the speed with which both federal voting registrars were imposed on the segregated South and the Voting Rights Act was passed largely fit the same mold. The widespread voter-registration drives, Freedom Rides, and sit-ins were the product of a great many centers of initiative and imitation. Efforts to coordinate, let alone organize, this bevy of defiance eluded many of the ad hoc bodies established for this purpose, such as the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, let alone the older, mainstream civil rights organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the Congress on Racial Equality, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. The enthusiasm, spontaneity, and creativity of the cascading social movement ran far ahead of the organizations wishing to represent, coordinate, and channel it.

Again, it was the widespread disruption, caused in large part by the violent reaction of segregationist vigilantes and public authorities, that created a crisis of public order throughout much of the South. Legislation that had languished for years was suddenly rushed through Congress as John and Robert Kennedy strove to contain the growing riots and demonstrations, their resolve stiffened by the context of the Cold War propaganda war in which the violence in the south could plausibly be said to characterize a racist state. Massive disorder and violence achieved, in short order, what decades of peaceful organizing and lobbying had failed to attain.

I began this essay with the fairly banal example of crossing against the traffic lights in Neubrandenburg. The purpose was not to urge lawbreaking for its own sake, still less for the petty reason of saving a few minutes. My purpose was rather to illustrate how ingrained habits of automatic obedience could lead to a situation that, on reflection, virtually everyone would agree was absurd. Virtually all the great emancipatory movements of the past three centuries have initially confronted a legal order, not to mention police power, arrayed against them. They would scarcely have prevailed had not a handful of brave souls been willing to breach those laws and customs (e.g., through sit-ins, demonstrations, and mass violations of passed laws). Their disruptive actions, fueled by indignation, frustration, and rage, made it abundantly clear that their claims could not be met within the existing institutional and legal parameters. Thus, immanent in their willingness to break the law was not so much a desire to sow chaos as a compulsion to instate a more just legal order. To the extent that our current rule of law is more capacious and emancipatory than its predecessors were, we owe much of that gain to lawbreakers.

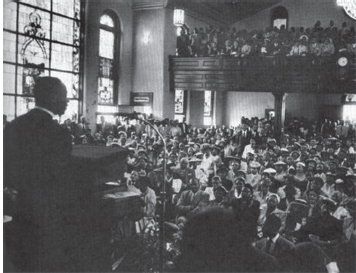

Riots and disruption are not the only way the unheard make their voices felt. There are certain conditions in which elites and leaders are especially attentive to what they have to say, to their likes and dislikes. Consider the case of charisma. It is common to speak of someone possessing charisma in the same way he could be said to have a hundred dollars in his pocket or a BMW in his garage. In fact, of course, charisma is a relationship; it depends absolutely on an audience and on culture. A charismatic performance in Spain or Afghanistan might not be even remotely charismatic in Laos or Tibet. It depends, in other words, on a response, a resonance with those witnessing the performance. And in certain circumstances elites work very hard to elicit that response, to find the right note, to harmonize their message with the wishes and tastes of their listeners and spectators. At rare moments, one can see this at work in real time. Consider the case of Martin Luther King, Jr., for certain audiences perhaps the most charismatic American public political figure of the twentieth century. Thanks to Taylor Branch’s sensitive and detailed biography of King and the movement, we can actually see this searching for the right note at work in real time and in the call-and-response tradition of the African American church. I excerpt, at length, Branch’s account of the speech King gave at the Holt Street YMCA in December 1955, after the conviction of Rosa Parks and on the eve of the Montgomery bus boycott:

“We are here this evening—for serious business,” he said, in even pulses, rising and then falling in pitch. When he paused, only one or two “yes” responses came up from the crowd, and they were quiet ones. It was a throng of shouters he could see, but they were waiting to see where he would take them. [He speaks of Rosa Parks as a fine citizen.]

“And I think I speak with—with legal authority—not that I have any legal authority … that the law has never been totally clarified.” This sentence marked King as a speaker who took care with distinctions, but it took the crowd nowhere. “Nobody can doubt the height of her character, no one can doubt the depth of her Christian commitment.”

“That’s right,” a soft chorus answered.

“And just because she refused to get up, she was arrested,” King repeated. The crowd was stirring now, following King at the speed of a medium walk.

He paused slightly longer.

“And you know, my friends, there comes a time,” he cried, “when people get tired of being trampled over by the iron feet of oppression.”

A flock of “Yeses” was coming back at him when suddenly the individual responses dissolved into a rising cheer and applause exploded beneath that cheer—all within the space of a second. The startling noise rolled on and on, like a wave that refused to break, and just when it seemed that the roar must finally weaken, a wall of sound came in from the enormous crowd outdoors to push the volume still higher. Thunder seemed to be added to the lower register—the sound of feet stomping on the wooden floor—until the loudness became something that was not so much heard as sensed by vibrations in the lungs. The giant cloud of noise shook the building and refused to go away. One sentence had set it loose somehow, pushing the call-and-response of the Negro church past the din of a political rally and on to something else that King had never known before. There was a rabbit of enormous proportions in those bushes. As the noise finally fell back, King’s voice rose above it to fire again. “There comes a time, my friends, when people get tired of being thrown across the abyss of humiliation, when they experience the bleakness of nagging despair,” he declared. “There comes a time when people get tired of getting pushed out of the glittering sunlight of life’s July, and left standing amidst the piercing chill of an Alpine November. There—” King was making a new run, but the crowd drowned him out. No one could tell whether the roar came in response to the nerve he had touched or simply out of pride in the speaker from whose tongue such rhetoric rolled so easily. “We are here—we are here because we are tired now,” King repeated [fig. 1.2].3

The pattern Branch so vividly depicts here is repeated in the rest of this particular speech and in most of King’s speeches. Charisma is a kind of perfect pitch. King develops a number of themes and a repertoire of metaphors for expressing them. When he senses a powerful response he repeats the theme in a slightly different way to sustain the enthusiasm and elaborate it. As impressive as his rhetorical creativity is, it is utterly dependent on finding the right pitch that will resonate with the deepest emotions and desires of his listeners. If we take a long view of King as a spokesman for the black Christian community, the civil rights movement, and nonviolent resistance (each a somewhat different audience), we can see how, over time, the seemingly passive listeners to his soaring oratory helped write his speeches for him. They, by their responses, selected the themes that made the vital emotional connection, themes that King would amplify and elaborate in his unique way. The themes that resonated grew; those that elicited little response were dropped from King’s repertoire. Like all charismatic acts, it was in two-part harmony.

The key condition for charisma is listening very carefully and responding. The condition for listening very carefully is a certain dependence on the audience, a certain relationship of power. One of the characteristics of great power is not having to listen. Those at the bottom of the heap are, in general, better listeners than those at the top. The daily quality of the lifeworld of a slave, a serf, a sharecropper, a worker, a domestic depends greatly on an accurate reading of the mood and wishes of the powerful, whereas slave owners, landlords, and bosses can often ignore the wishes of their subordinates. The structural conditions that encourage such attentiveness are therefore the key to this relationship. For King, the attentiveness was built into being asked to lead the Montgomery bus boycott and being dependent on the enthusiastic participation of the black community.

Figure 1.2. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., delivering his last sermon, Memphis, Tennessee, April 3, 1968. Photograph from blackpast.org

To see how such counterintuitive “speechwriting” works in other contexts, let’s imagine a bard in the medieval marketplace who sings and plays music for a living. Let’s assume also, for purposes of illustration, that the bard in question is a “downmarket” performer—that he plays in the poor quarters of the town and is dependent on a copper or two from many of his listeners for his daily bread. Finally, let’s further imagine that the bard has a repertoire of a thousand songs and is new to the town.

My guess is that the bard will begin with a random selection of songs or perhaps the ones that were favored in the previous towns he visited. Day after day he observes the response of his listeners and the number of coppers in his hat at the end of the day. Perhaps they make requests. Over time, surely, the bard, providing only that he is self-interestedly attentive, will narrow his performance to the tunes and themes favored by his audience—certain songs will drop out of his active repertoire and others will be performed repeatedly. The audience will have, again over time, shaped his repertoire in accordance with their tastes and desires in much the way that King’s audience, again over time, shaped his speeches. This rather skeletal story doesn’t allow for the creativity of the bard or orator constantly trying out new themes and developing them or for the evolving tastes of the audience, but it does illustrate the essential reciprocity of charismatic leadership.

The illustrative “bard” story is not far removed from the actual experience of a Chinese student sent to the countryside during the Cultural Revolution. Being of slight build and having no obvious skills useful to villagers, he was at first deeply resented as another mouth to feed while contributing nothing to production. Short of food themselves, the villagers gave him little or nothing to eat, and he was gradually wasting away. He discovered, however, that the villagers liked to hear his late evening recitations of traditional folktales, of which he knew hundreds. To keep him reciting in the evening, they would feed him small snacks to supplement his starvation rations. His stories literally kept him alive. What’s more, his repertoire, as with our mythical bard, came over time to accord with the tastes of his peasant audience. Some of his tales left them cold, and him unfed. Some tales they loved and wanted to have told again and again. He literally sang for his supper, but the villagers, as it were, called the tune. When private trade and markets were later allowed, he told tales in the district marketplace to a larger and different audience. Here, too, his repertoire accommodated itself to his new audience.4

Politicians, anxious for votes in tumultuous times when tried-and-true themes seem to carry little resonance, tend, like a bard or Martin Luther King, Jr., to keep their ears firmly to the ground to assess what moves the constituents whose support and enthusiasm they need. Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s first campaign for the U.S. presidency, at the beginning of the Great Depression, is a striking case in point. At the outset of the campaign, Roosevelt was a rather conservative Democrat not inclined to make promises or claims that were radical. In the course of the campaign, however, which was mostly conducted at whistle-stops, owing to the candidate’s paralysis, the Roosevelt standard speech evolved, becoming more radical and expansive. Roosevelt and his speechwriters worked feverishly, trying new themes, new phrasings, and new claims at whistle-stop after whistle-stop, adjusting the speech little by little, depending on the response and the particular audience. In an era of unprecedented poverty and unemployment, FDR confronted an audience that looked to him for hope and the promise of assistance, and gradually his stump speech came to embody those hopes. At the end of the campaign, his oral “platform” was far more radical than it had been at the outset. There was a real sense in which, cumulatively, the audience at the whistle-stops had written (or shall we say “selected”) his speech for him. It wasn’t just the speech that was transformed but Roosevelt himself, who now saw himself embodying the aspirations of millions of his desperate countrymen.

This particular form of influence from below works only in certain conditions. If the bard is hired away by the local lord to sing him praise songs in return for room and board, the repertoire would look very different. If a politician lives or dies largely by huge donations designed as much to shape public opinion as to accommodate it, he or she will pay less attention to rank-and-file supporters. A social or revolutionary movement not yet in power is likely to have better hearing than one that has come to power. The most powerful don’t have to learn how to carry a tune. Or, as Kenneth Boulding put it, “the larger and more authoritarian an organization [or state], the better the chance that its top decision-makers will be operating in purely imaginative worlds.”5