I live in small inland town in Connecticut called Durham, after its much larger and better-known English namesake. Whether out of nostalgia for the landscape left behind or a lack of imagination, there is scarcely a town in Connecticut that does not simply appropriate an English place-name. Native American landscape terms tend to survive only in the names of lakes and rivers, or in the name of the state itself. It is a rare colonial enterprise that does not attempt to rename the landscape as a means of asserting its ownership and making it both familiar and legible to the colonizers. In settings as disparate as Ireland, Australia, and the Palestinian West Bank, the landscape has been comprehensively renamed in an effort to smother the older vernacular terms.

Consider, by way of illustration, the vernacular and official names for roads. A road runs between my town of Durham and the coastal town of Guilford, some sixteen miles to the south. Those of us who live in Durham call this road (among ourselves) the “Guilford Road” because it tells us exactly where we’ll get to if we take it. The same road at its Guilford terminus is naturally called the “Durham Road” because it tells the inhabitants of Guilford exactly where they’ll get to if they take it. One imagines that those who live midway along the road call it the “Durham Road” or the “Guilford Road” depending on which way they are heading. That the same road has two names depending on one’s location demonstrates the situational, contingent nature of vernacular naming practices; each name encodes valuable local knowledge—perhaps the most important single thing you would want to know about a road is where it leads. Vernacular practices not only produce one road with two names but many roads with the same name. Thus, the nearby towns of Killingworth, Haddam, Madison, and Meriden each have roads leading to Durham that the local inhabitants call the “Durham Road.”

Now imagine the insuperable problems that this locally effective folk system would pose to an outsider requiring a unique and definitive name for each road. A state road repair crew sent to fix potholes on the “Durham Road” would have to ask, “Which Durham Road?” Thus it comes as no surprise that the road between Durham and Guilford is reincarnated on all state maps and in all official designations as “Route 77.” The naming practices of the state require a synoptic view, a standardized scheme of identification generating mutually exclusive and exhaustive designations. As Route 77, the road no longer immediately conveys where it leads; the sense of Route 77 only springs into view once we spread out a road map on which all state roads are enumerated. And yet the official name can be of vital importance. If you are gravely injured in a car crash on the Durham-Guilford Road, you will want to tell the state-dispatched ambulance team unambiguously that the road on which you are in danger of bleeding to death is Route 77.

Vernacular and official naming schemes jostle one another in many contexts. Vernacular names for streets and roads encode local knowledge. Some examples are Maiden Lane (the Lane where five spinster sisters once lived and walked, single file, to church every Sunday), Cider Hill Road (the road up the hill where the orchard and cider mill once stood), and Cream Pot Road (once the site of a dairy, where neighbors bought milk, cream, and butter). At the time when the name became fixed, it was probably the most relevant and useful name for local residents, though it might be mystifying to outsiders and recent arrivals. Other road names might refer to geographic features: Mica Ridge Road, Bare Rock Road, Ball Brook Road. The sum of roads and place-names in a small place, in fact, amounts to something of a local geography and history if one is familiar with the stories, features, episodes, and family enterprises encoded within them. For local people these names are rich and meaningful; for outsiders they are frequently illegible. The nonlocal planners, tax collectors, transportation managers, ambulance dispatchers, police officers, and firefighters, however, find a higher order of synoptic legibility far preferable. Given their way, they tend to prefer grids of parallel streets, consecutively numbered (First Street, Second Street), and compass directions (Northwest First Street, Northeast Second Avenue). Washington, D.C., is a particularly stunning example of such rational planning. New York City, by contrast, is a hybrid. Below Wall Street (marking the outer wall of the original Dutch settlement), the city is “vernacular” in its tangle of street forms and names, many of them originally footpaths; above Wall Street it is an easily legible, synoptic grid city of Cartesian simplicity, with avenues and streets at right angles to one another and enumerated, with a few exceptions, consecutively. Some midwestern towns, to relieve the monotony of numbered streets, have instead named them consecutively after presidents. As a bid for legibility, it is likely to appeal only to quiz show fans, who know when to expect “Polk,” “Van Buren,” “Taylor,” and “Cleveland” streets to pop up; as a pedagogical tool, there is something to be said for it.

Vernacular measurement is only as precise as it needs to be for the purposes at hand. It is symbolized in such expressions as a “pinch of salt,” “a stone’s throw,” “a book of hay,” “within shouting distance.” And for many purposes, vernacular rules may prove more accurate than apparently more exact systems. A case in point is the advice given by Squanto to white settlers in New England about when to plant a crop new to them, maize. He reportedly told them to “plant corn when the oak leaves were the size of a squirrel’s ear.” An eighteenth-century farmer’s almanac, by contrast, would typically advise planting, say, “after the first full moon in May,” or else would specify a particular date. One imagines that the almanac publisher would have feared, above all, a killing frost, and would have erred on the side of caution. Still, the almanac advice is, in its way, rigid: What about farms near the coast as opposed to those inland? What about fields on the north side of a hill that got less sun, or farms at higher elevations? The almanac’s one-size-fits-all prescription travels rather badly. Squanto’s formula, on the other hand, travels well. Wherever there are squirrels and oak trees and they are observed locally, it works. The vernacular observation, it turns out, is closely correlated with ground temperature, which governs oak leafing. It is based on a close observation of the sequence of spring events that are always sequential but may be early or delayed, drawn out or rushed, whereas the almanac relies on a universal calendrical and lunar system.

The order, rationality, abstractness, and synoptic legibility of certain kinds of schemes of naming, landscape, architecture, and work processes lend themselves to hierarchical power. I think of them as “landscapes of control and appropriation.” To take a simple example, the nearly universal system of permanent patronymic naming did not exist anywhere in the world before states found it useful for identification. It has spread along with taxes, courts, landed property, conscription, and police work—that is, along with the development of the state. It has now been superseded by identification numbers, photography, fingerprints, and DNA testing, but it was invented as a means of supervision and control. The resulting techniques represent a general capacity that can be used as easily to deliver vaccinations as to round up enemies of the regime. They centralize knowledge and power, but they are utterly neutral with respect to the purposes to which they are put.

The industrial assembly line is, from this perspective, the replacement of vernacular, artisanal production by a division of labor in which only the designing engineer controls the whole labor process and the workers on the floor become substitutable “hands.” It may, for some products, be more efficient than artisanal production, but there is no doubt that it always concentrates power over the work process in those who control the assembly line. The utopian management dream of perfect mechanical control was, however, unrealizable not just because trade unions intervened but also because each machine had its own particularities, and a worker who had a vernacular, local knowledge of this particular milling or stamping machine was valuable for that reason. Even on the line, vernacular knowledge was essential to successful production.

Where the uniformity of the product is of great concern and where much of the work can be undertaken in a setting specifically constructed for that purpose, as in the building of Henry Ford’s Model T or, for that matter, the construction of a Big Mac at a McDonald’s, the degree of control can be impressive. The layout, down to the minutest detail at a Mc-Donald’s franchise, is calculated to maximize control over the materials and the work process from the center. That is, the district supervisor who arrives for an inspection with his handy clipboard can evaluate the franchise according to a protocol that has been engineered into the design itself. The coolers are uniform and their location is prescribed. The same goes for the deep fryers, the grills, the protocol for their cleaning and maintenance, the paper wrappers, etc., etc. The platonic form of the perfect McDonald’s franchise and the perfect Big Mac has been dreamed up at central headquarters and engineered into the architecture, layout, and training so that the clipboard scoring can be used to judge how close it has come to the ideal. In its immanent logic, Fordist production and the McDonald’s module is, as E. F. Schumacher noted in 1973, “an offensive against the unpredictability, unpunctuality, general waywardness and cussedness of living nature, including man.” 1

It is no exaggeration, I think, to view the past three centuries as the triumph of standardized, official landscapes of control and appropriation over vernacular order. That this triumph has come in tandem with the rise of large-scale hierarchical organizations, of which the state itself is only the most striking example, is entirely logical. The list of lost vernacular orders is potentially staggering. I venture here only the beginning of such a list and invite readers, if they have the appetite, to supplement it. National standard languages have replaced local tongues. Commoditized freehold land tenure has replaced complex local land-use practices, planned communities and neighborhoods have replaced older, unplanned communities and neighborhoods, and large factories and farms have replaced artisanal production and smallholder, mixed farming. Standard naming and identification practices have replaced innumerable local naming customs. National law has replaced local common law and tradition. Large schemes of irrigation and electricity supply have replaced locally adapted irrigation systems and fuel gathering. Landscapes relatively resistant to control and appropriation have been replaced with landscapes that facilitate hierarchical coordination.

It is perfectly clear that large-scale modernist schemes of imperative coordination can, for certain purposes, be the most efficient, equitable, and satisfactory solution. Space exploration, the planning of vast transportation networks, airplane manufacture, and other necessarily large-scale endeavors may well require huge organizations minutely coordinated by a few experts. The control of epidemics or of pollution requires a center staffed by experts receiving and digesting standard information from hundreds of reporting units.

Where such schemes run into trouble, sometimes catastrophic trouble, is when they encounter a recalcitrant nature, the complexity of which they only poorly comprehend, or when they encounter a recalcitrant human nature, the complexity of which they also poorly comprehend.

The troubles that have plagued “scientific” forestry, invented in the German lands in the late eighteenth century, and some forms of plantation agriculture typify the encounter. Wanting to maximize revenue from the sale of firewood and lumber from domain forests, the originators of scientific forestry reasoned that, depending on the soil, either the Norway spruce or the Scotch pine would provide the maximum cubic meters of timber per hectare. To this end, they clear-cut mixed forests and planted a single species simultaneously and in straight rows (as with row crops). They aimed at a forest that was easy to inspect, could be felled at a given time, and would produce a uniform log from a standardized tree (the Normalbaum). For a while—nearly an entire century—it worked brilliantly. Then it faltered. It turned out that the first rotation had apparently profited from the accumulated soil capital of the mixed forest it had replaced without replenishment. The single-species forest was above all a veritable feast for the pests, rusts, scales, and blights that specialized in attacking the Scotch pine or the Norway spruce. A forest of trees all the same age was also far more susceptible to catastrophic storm and wind damage. In an effort to simplify the forest as a one-commodity machine, scientific forestry had radically reduced its diversity. The lack of tree species diversity was replicated at every level in this stripped-down forest: in the poverty of insect species, of birds, of mammals, of lichen, of mosses, of fungi, of flora in general. The planners had created a green desert, and nature had struck back. In little more than a century, the successors of those who had made scientific forestry famous in turn made the terms “forest death” (Waldsterben) and “restoration forestry” equally famous (fig. 2.1).

Figure 2.1. Scientific forest, Lithuania. Photograph © Alfas Pliura

Henry Ford, bolstered by the success of the Model T and wealth beyond imagining, ran into much the same problem when he tried translating his success in building cars in factories to growing rubber trees in the tropics. He bought a tract of land roughly the size of Connecticut along a branch of the Amazon and set about creating Fordlandia. If successful, his plantation would have supplied enough latex to equip all his autos with tires for the foreseeable future. It proved an unmitigated disaster. In their natural habitat in the Amazon basin, rubber trees grow here and there among mixed stands of great diversity. They thrive amid this variety in part because they are far enough apart to minimize the buildup of diseases and pests that favor them in this, their native habitat. Transplanted to Southeast Asia by the Dutch and the British, rubber trees did relatively well in plantation stands precisely because they did not bring with them the full complement of pests and enemies. But concentrated as row crops in the Amazon, they succumbed in a few years to a variety of diseases and blights that even heroic and expensive efforts at triple grafting (one canopy stock grafted to another trunk stock, and both grafted to a different root stock) could not overcome.

In the contrived and man-made auto-assembly plant in River Rouge, built for a single purpose, the environment could, with difficulty, be mastered. In the Brazilian tropics, it could not. After millions had been invested, after innumerable changes in management and reformulated plans, after riots by the workforce, Henry Ford’s adventure in Brazil was abandoned.

Henry Ford started with what his experts judged to be the best rubber tree and then tried to reshape the environment to suit it. Compare this logic to its mirror image: starting with the environmental givens and then selecting the cultivars that best fit a given niche. Customary practices of potato cultivation in the Andes represent a fine example of vernacular, artisanal farming. A high-altitude Andean potato farmer might cultivate as many as fifteen small parcels, some on a rotating basis. Each parcel is distinct in terms of its soil, altitude, orientation to sun and wind, moisture, slope, and history of cultivation. There is no “standard field.” Choosing from among a large number of locally developed landraces, each with different and well-known characteristics, the farmer makes a series of prudent bets, planting anywhere from one cultivar to as many as a dozen in a single field. Each season is the occasion for a new round of trials, with last season’s results in terms of yield, disease, prices, and response to changed plot conditions carefully weighed. These farms are market-oriented experiment stations with good yields, great adaptability, and reliability. At least as important, they are not merely producing crops; they are reproducing farmers and communities with plant-breeding skills, flexible strategies, ecological knowledge, and considerable self-confidence and autonomy.

The logic of scientific extension agriculture in the Andes is analogous to Henry Ford’s Amazonian plantations. It begins with the idea of an “ideal” potato, defined largely but not entirely in terms of yield. Plant scientists then set about breeding a genotype that will most closely approximate the desired characteristics. That genotype is grown in experimental plots to determine the conditions that best allow it to flourish. The main purpose of extension work, then, to retrofit the entire environment of the farmer’s field so as to realize the potential of the new genotype. This may require the application of nitrogen fertilizer, herbicides, and pesticides, special field and soil preparation, irrigation, and the timing of cultivation (planting, watering, weeding, harvesting). As one might expect, each new “ideal” cultivar usually fails within three or four years as pests and diseases gain on it, to be replaced in turn with a newer ideal potato and the cycle begins again. To the degree that it succeeds, it turns the fields into standard fields and the farmers into standard farmers, just as Henry Ford standardized the work environment and workers in River Rouge. The assembly line and the monoculture plantation each require, as a condition of their existence, the subjugation of both the vernacular artisan and of the diverse, vernacular landscape.

It turns out that it is not only plants that seem to thrive best in settings of diversity. Human nature as well seems to shun a narrow uniformity in favor of variety and diversity.

The high tide of modernist urban planning spans the first half of the twentieth century, when the triumph of civil engineering, a revolution in building techniques and materials, and the political ambitions to remake urban life combined to transform cities throughout the West. In its ambitions, it bears more than a family resemblance to scientific forestry and plantation agriculture. The emphasis was on visual order and the segregation of function. Visually, a theme to which I shall return, utopian planners favored “the sublime straight line,” right angles, and sculptural regularity. When it came to spatial layout, virtually all planners favored the strict separation of diffferent spheres of urban activity: residential housing, commercial retail space, office space, entertainment, government offices, and ceremonial space. One can easily see why this was convenient for the planners. So many retail outlets serving so many customers could be reduced to something of an algorithm requiring so many square feet per store, so many square feet of shelf space, planned transportation links, and so forth; residences required so many square feet of living space per (standardized) family, so much sunlight, so much water, so much kitchen space, so many electric outlets, so much adjacent playground space. Strict segregation of functions minimized the variables in the algorithm: it was easier to plan, easier to build, easier to maintain, easier to police, and, they thought, easier on the eye. Planning for single uses facilitated standardization, while by comparison, planning a complex, mixed-use town in these terms would have been a nightmare.

There was one problem. People tended to hate such cities and shunned them when they could. When they couldn’t, they found other ways to express their despair and contempt. It is said that the postmodern era began at precisely 3 p.m. on March 16, 1972, when the award-winning Pruitt-Igoe high-rise public housing project in St. Louis was finally and officially dynamited to a heap of rubble. Its inhabitants had, in effect, reduced it to a shell. The Pruitt-Igoe buildings were merely the flagship for an entire fleet of isolated, single-use, high-rise public housing apartment blocks that seemed degrading warehouses to most of their residents and that have now largely been demolished.

At the same time that these housing projects, sailing under the banner of “slum clearance” and the elimination of “urban blight,” were being constructed, they were subjected to a comprehensive and ultimately successful critique by urbanists like Jane Jacobs, who were more interested in the vernacular city: in daily urban life, and in how the city actually functioned more than in how it looked. Urban planning, like most official schemes, was characterized by a self-conscious tunnel vision. That is, it focused relentlessly on a single objective and design with a view to maximizing that objective. If the objective was growing corn, the goal became growing the most bushels per acre; if it was Model Ts, it was producing the most Model Ts for the labor and input costs; if it was health care delivery, a hospital was designed solely for efficiency in treatment; if it was the production of lumber, the forest was redesigned to be a one-commodity machine.

Jacobs understood three things that these modernist planners were utterly blind to. First, she identified the fatal assumption that in any such activity there is only one thing going on, and the objective of planning is to maximize the efficiency of its delivery. Unlike the planners whose algorithms depended on stipulated efficiencies—how long it took to get to work from home, how efficiently food could be delivered to the city—she understood there were a great many human purposes embedded in any human activity. Mothers or fathers pushing baby carriages may simultaneously be talking to friends, doing errands, getting a bite to eat, and looking for a book. An office worker may find lunch or a beer with co-workers the most satisfying part of the day. Second, Jacobs grasped that it was for this reason, as well as for the sheer pleasure of navigating in an animated, stimulating, and varied environment, that complex, mixed-use districts of the city were often the most desirable locations. Successful urban neighborhoods—ones that were safe, pleasant, amenity-rich, and economically viable—tended to be dense, mixed-use areas, with virtually all the urban functions concentrated and mixed higgledy-piggledy. Moreover, they were also dynamic over time. The effort to specify and freeze functions by planning fiat Jacobs termed “social taxidermy.”

Finally, she explained that if one started from the “lived,” vernacular city, it became clear that the effort by urban planners to turn cities into disciplined works of art of geometric, visual order was not just fundamentally misguided, it was an attack on the actual, functioning vernacular order of a successful urban neighborhood.

Looked at from this angle, the standard practice of urban planning and architecture suddenly seems very bizarre indeed. The architect and planners proceed by devising an overall vision of the building or ensemble of buildings they propose. This vision is physically represented in drawings and, typically, in an actual model of the buildings proposed. One sees in the newspapers photographs of beaming city officials and architects looking down on the successful model as if they were in helicopters, or gods. What is astounding, from a vernacular perspective, is that no one ever experiences the city from that height or angle. The presumptive ground-level experience of real pedestrians—window-shoppers, errand-runners, aimlessly strolling lovers—is left entirely out of the urban-planning equation. It is substantially as sculptural miniatures that the plans are seen, and it is hardly surprising that they should be appreciated for their visual appeal as attractive works of art: works of art that will henceforth never be seen again from that godlike vantage point, except by Superman.

This logic of modeling and miniaturization as a characteristic of official forms of order is, I think, diagnostic. The real world is messy and even dangerous. Mankind has a long history of miniaturization as a form of play, control, and manipulation. It can be seen in toy soldiers, model tanks, trucks, cars, warships and planes, dollhouses, model railroads, and so on. Such toys serve the entirely admirable purpose of letting us play with representations when the real thing is inaccessible or dangerous, or both. But miniaturization is very much a game for grown-ups, presidents, and generals as well. When the effort to transform a recalcitrant and intractable world is frustrated, elites are often tempted to retreat to miniatures, some of them quite grandiose. The effect of this retreat is to create small, relatively self-contained utopian spaces where the desired perfection might be more nearly realized. Model villages, model cities, military colonies, show projects, and demonstration farms offer politicians, administrators, and specialists a chance to create a sharply defined experimental terrain where the number of rogue variables and unknowns is minimized. The limiting case, where control is maximized but impact on the external world is minimized, is the museum or theme park. Model farms and model towns have, of course, a legitimate role as experiments where ideas about production, design, and social organization can be tested at low risk and scaled up or abandoned, depending on how they fare. Just as often, however, as with many “designer” national capitals (e.g., Washington, D.C., St. Petersburg, Dodoma, Brasilia, Islamabad, New Delhi, Abuja), they become stand-alone architectural and political statements at odds, and often purposely so, with their larger environment. The insistence on a rigid visual aesthetic at the core of the capital city tends to produce a penumbra of settlements and slums teeming with squatters, people who, as often as not, sweep the floors, cook the meals, and tend the children of the elites who work at the decorous, planned center. Order at the center is in this sense deceptive, being sustained by nonconforming and unacknowledged practices at the periphery.

Governing a large state is like cooking a small fish.

Tao Te Ching

The more highly planned, regulated, and formal a social or economic order is, the more likely it is to be parasitic on informal processes that the formal scheme does not recognize and without which it could not continue to exist, informal processes that the formal order cannot alone create and maintain. Here language acquisition is an instructive metaphor. Children do not begin by learning the rules of grammar and then using these rules to construct a successful sentence. They learn to speak the way they learn to walk: by imitation, trial, error, and endless practice. The rules of grammar are the regularities that can be observed in successful speaking, they are not the cause of successful speech.

Workers have seized on the inadequacy of the rules to explain how things actually run and have exploited it to their advantage. Thus, the taxi drivers of Paris have, when they were frustrated with the municipal authorities over fees or new regulations, resorted to what is known as a grève de zèle. They would all, by agreement and on cue, suddenly begin to follow all the regulations in the code routier, and, as intended, this would bring traffic in Paris to a grinding halt. Knowing that traffic circulated in Paris only by a practiced and judicious disregard of many regulations, they could, merely by following the rules meticulously, bring it to a standstill. The English-language version of this procedure is often known as the “work-to-rule” strike. In an extended work-to-rule action against the Caterpillar Corporation, workers reverted to following the inefficient procedures specified by engineers, knowing that it would cost the company valuable time and quality, rather than continuing the more expeditious practices they had long ago devised on the job. The actual work process in any office, on any construction site, or on any factory floor cannot be adequately explained by the rules, however elaborate, governing it; the work gets done only because of the effective informal understandings and improvisations outside those rules.

The planned economies of the socialist bloc before the breach in the Berlin Wall in 1989 were a striking example of how rigid production norms were sustained only by informal arrangements wholly outside the official scheme. In one typical East German factory, the two most indispensable employees were not even part of the official organizational chart. One was a “jack-of-all trades” adept at devising short-term, jury-rigged solutions to keep machines running, to correct production flaws, and to make substitute spare parts. The second indispensable employee used factory funds to purchase and store desirable nonperishable goods (e.g., soap powder, quality paper, good wine, yarn, medicines, fashionable clothes) when they were available. Then, when the factory absolutely needed a machine, spare parts, or raw material not available through the plan to meet its quotas and earn its bonuses, this employee packed the hoarded goods in a Trabant and went seeking to barter them for the necessary factory supplies. Were it not for these informal arrangements, formal production would have ceased.

Like the city official peering down at the architect’s proposed model of a new development site, we are all prone to the error of equating visual order with working order and visual complexity with disorder. It is a natural and, I believe, grave mistake, and one strongly associated with modernism. How dubious such an association is requires but a moment’s reflection. Does it follow that more learning is taking place in a classroom with uniformed students seated at desks arranged in neat rows than in a classroom with un-uniformed students sitting on the floor or around a table? The great critic of modern urban planning, Jane Jacobs, warned that the intricate complexity of a successful mixed-use neighborhood was not, as the aesthetic of many urban planners supposed, a representation of chaos and disorder. It was, though unplanned, a highly elaborated and resilient form of order. The apparent disorder of leaves falling in the autumn, of the entrails of a rabbit, of the interior of a jet engine, of the city desk of a major newspaper is not disorder at all but rather an intricate functional order. Once its logic and purpose are grasped, it actually looks different and reflects the order of its function.

Take the design of field crops and gardens. The tendency of modern “scientific” agriculture has favored large, capital-intensive fields, with a single crop, often a hybrid or clone for maximum uniformity, grown in straight rows for easy tillage and machine harvesting. The use of fertilizers, irrigation, pesticides, and herbicides serves to make the field conditions as suitable to the single cultivar and as uniform as possible. It is a generic module of farming that travels well and actually works tolerably well for what I think of as “proletarian” production crops such as wheat, corn, cotton, and soybeans that tolerate rough handling. The effort of this agriculture to rise above, as it were, local soils, local landscape, local labor, local implements, and local weather makes it the very antithesis of vernacular agriculture. The Western vegetable garden has some, not all, of the same features. Though it contains many cultivars they are typically planted in straight rows, one cultivar to a row, and look rather like a military regiment drawn up for inspection at a parade. The geometric order is often a matter of pride. Again, there is a striking emphasis on visual regularity from above and outside.

Contrast this with, say, the indigenous field crops of tropical West Africa as encountered by British agricultural extension agents in the nineteenth century. They were shocked. Visually, the fields seemed a mess: there were two, three, and sometimes four crops crowded into the field at a time, other crops were planted in relays, small bunds—embankments—of sticks were scattered here and there, small hillocks appeared to be scattered at random. Since to a Western eye the fields were obviously a mess; the assumption was that the cultivators were themselves negligent and careless. The extension agents set about teaching them proper, “modern” agricultural techniques. It was only after roughly thirty years of frustration and failure that a Westerner thought to actually examine, scientifically, the relative merits of the two forms of cultivation under West African conditions. It turned out that the “mess” in the West African field was an agricultural system finely tuned to local conditions. The polycropping and relay cropping ensured there was ground cover to prevent erosion and capture rainfall year-round; one crop provided nutrients to another or shaded it; the bunds prevented gully erosion; cultivars were scattered to minimize pest damage and disease.

Not only were the methods sustainable, the yields compared favorably with the yields of crops grown by the Western techniques preferred by the extension agents. What the extension agents had done was erroneously to associate visual order with working order and visual disorder with inefficiency. The Westerners were in the grip of a quasi-religious faith in crop geometry, while the West Africans had worked out a highly successful system of cultivation without regard to geometry.

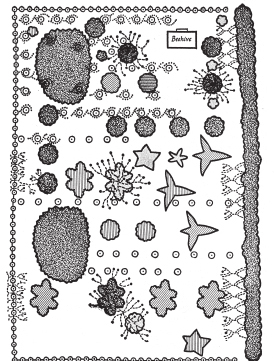

Edgar Anderson, a botanist interested in the history of maize in Central America, stumbled across a peasant garden in Guatemala that demonstrated how apparent visual disorder could be the key to a finely tuned working order. Walking by it on his way to the fields of maize each day, he at first took it to be an overgrown, vegetable dump heap. Only when he saw someone working in it did he realize that it was not just a garden but a brilliantly conceived garden despite, or rather because of, its visual disorder from a Western gardening perspective. I cannot do better than to quote him at length about the logic behind the garden and reproduce his diagrams of its layout (fig. 2.2).

Figure 2.2. Edgar Anderson’s drawings for the Vernacular Garden, Guatemala. (a) Above An orchard garden. (b) Right Detailed glyphs identifying the plants and their categories in the garden. Reprinted from Plants, Man, and Life, by Edgar Anderson, published by the University of California Press; reprinted with permission of the University of California Press

Though at first sight there seems little order; as soon as we started mapping the garden, we realized that it was planted in fairly definite cross-wise rows. There were fruit trees, native and European in great variety: annonas, cheromoyas, avocados, peaches, quinces, plums, a fig, and a few coffee bushes. There were giant cacti grown for their fruit. There was a large plant of rosemary, a plant of rue, some poinsettias, and a semi-climbing tea rose. There was a whole row of the native domesticated hawthorn, whose fruit like yellow, doll-sized apples make a delicious conserve. There were two varieties of corn, one well past bearing and now serving as a trellis for climbing string beans which were just coming into season, the other, a much taller sort, which was tasseling out. There were specimens of a little banana with smooth wide leaves which are the local substitute for wrapping paper, and are also used instead of cornhusks in cooking the native variant of hot tamales. Over it all clambered the luxuriant vines of various cucurbits. Chayote, when finally mature has a nutritious root weighing several pounds. At one point there was a depression the size of a small bathtub where a chayote root had recently been excavated; this served as a dump heap and compost for waste from the house. At one end of the garden was a small beehive made from boxes and tin cans. In terms of our American and European equivalents, the garden was a vegetable garden, an orchard, a medicinal garden, a dump heap, a compost heap, and a beeyard. There was no problem of erosion though it was at the top of a steep slope; the soil surface was practically all covered and apparently would be during most of the year. Humidity would be kept during the dry season and plants of the same sort were so isolated from one another by intervening vegetation that pests and diseases could not readily spread from plant to plant. The fertility was being conserved; in addition to the waste from the house, mature plants were being buried in between the rows when their usefulness was over.

It is frequently said by Europeans and European Americans that time means nothing to an Indian. This garden seemed to me to be a good example of how the Indian, when we look more than superficially into his activities, is budgeting time more efficiently than we do. The garden was in continuous production but was taking only a little effort at any one time: a few weeds pulled when one came down to pick the squashes, corn and bean plants dug in between the rows when the last of the climbing beans was picked, and a new crop of something else planted above them a few weeks later.2

Over the past two centuries, vernacular practices have been extinguished at such a rate that one can, with little exaggeration, think of the process as one of mass extinction akin to the accelerated disappearance of species. And the cause is also analogous: the loss of habitat. Many vernacular practices have made their final exit, and others are endangered.

The principal agent behind their extinction is none other than the anarchists’ sworn enemy, the state, and in particular the modern nation-state. The rise of the modern and now hegemonic political module of the nation-state displaced and then crushed a host of vernacular political forms: stateless bands, tribes, free cities, loose confederations of towns, maroon communities, empires. In their place stands everywhere a single vernacular: the North Atlantic nation-state, codified in the eighteenth century and masquerading as a universal. It is, if we run back several hundred yards and open our eyes in wonder, nothing short of amazing that one can travel anywhere in the world and encounter virtually the same institutional order: a national flag, a national anthem, national theaters, national orchestras, heads of state, a parliament (real or fictitious), a central bank, a league table of similar ministries similarly organized, a security apparatus, and so on. Colonial empires and “modernist” emulation played a role in propagating the module, but its staying power depends on the fact that such institutions are the universal gears that integrate a political unit into the established international systems. Until 1989 there were two poles of emulation. In the socialist bloc one could go from Czechoslovakia to Mozambique, to Cuba, to Vietnam, to Laos, to Mongolia and find roughly the same central planning apparatus, collective farms, and five-year plans. Since then, with few exceptions, a single standard has prevailed.

Once in place, the modern (nation-) state set about homogenizing its population and the people’s deviant, vernacular practices. Nearly everywhere, the state proceeded to fabricate a nation: France set about creating Frenchmen, Italy set about creating Italians.

This entailed a great project of homogenization. A huge variety of languages and dialects, often mutually unintelligible, were, largely through schooling, subordinated to a standardized national language—often the dialect of the dominant region. This led to the disappearance of languages; of local literatures, oral and written; of music; of legends and epics; of whole worlds of meaning. A huge variety of local laws and customary practices were replaced by a national system of law that was, in principle at least, everywhere the same. A huge variety of land-use practices were replaced by a national system of land titling, registration, and transfer, the better to facilitate taxation. A huge number of local pedagogies—apprenticeships, tutoring by traveling “masters,” healing, religious instruction, informal classes—were typically replaced by a national school system in which a French minister of education could boast that, as it was 10:20 a.m., he knew exactly which passage of Cicero all students of a certain form throughout France would be studying. This utopian image of uniformity was seldom achieved, but what these projects did accomplish was the destruction of vernaculars.

Beyond the nation-state itself, the forces of standardization are today represented by international organizations. It is the principal aim of institutions such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the World Trade Organization, UNESCO, and even UNICEF and the World Court to propagate normative (“best practice”) standards, once again deriving from the North Atlantic nations, throughout the globe. The financial muscle of these agencies is such that failure to conform to their recommendations carries substantial penalties in loans and aid forgone. The process of institutional alignment now goes by the charming euphemism of “harmonization.” Global corporations are instrumental as well in this project of standardization. They too thrive in a familiar and homogenized cosmopolitan setting where the legal order, the commercial regulations, the currency system, and so on are uniform. They are also, through their sales of goods, services, and advertising, constantly working to fabricate consumers, whose needs and tastes are what they require.

The disappearance of some vernaculars need hardly be mourned. If the standardized model of the French citizen bequeathed to us by the Revolution replaced vernacular forms of patriarchal servitude in provincial France, then surely this was an emancipatory gain. If technical improvements like matches and washing machines replaced flint and tinder and washboards, it surely meant less drudgery. One would not want to spring to the defense of all vernaculars against all universals.

The powerful agencies of homogenization, however, are not so discriminating. They have tended to replace virtually all vernaculars with what they represent as universal, but let us recall again that in most cases it is a North Atlantic cross-dressed vernacular masquerading as a universal. The result is a massive diminution in cultural, political, and economic diversity, a massive homogenization in languages, cultures, property systems, political forms, and above all modes of sensibility and the lifeworlds that sustain them. One can look anxiously ahead to a time, not so far away, when the North Atlantic businessman can step off a plane anywhere in the world and find an institutional order—laws, commercial codes, ministries, traffic systems, property forms, land tenure—thoroughly familiar. And why not? The forms are essentially his own. Only the cuisine, the music, the dances, and native costumes will remain exotic and folkloric … and thoroughly commercialized as a commodity as well.