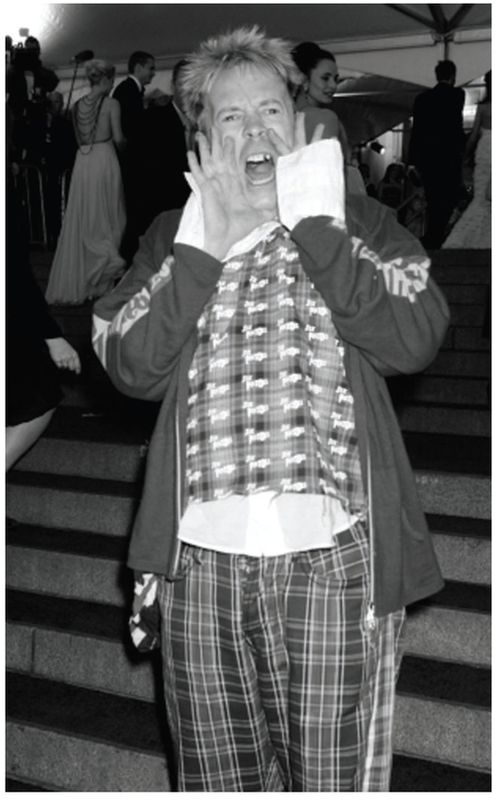

Lydon at the “Anglomania” party

The Ballroom Blitz: From New York To Baghdad

My name is Charles Giteau/ My name I’ll never deny, from the folk song ‘Charles Giteau’, attributed to Charles Guiteau, assassin of James A. Garfield, 20th president of the United States, who supposedly sang the song while awaiting execution.

‘Sex Pistols’ meant to me the idea of a pistol, a pinup, a young thing. A better looking assassin.” Malcolm McLaren, 1988

At least I got my name. No one can take my name off me. My name does mean something. It stands for something. It stands for something true. No one can take that away from me. Johnny Rotten, 2003

What The World Knows, The World Forgets

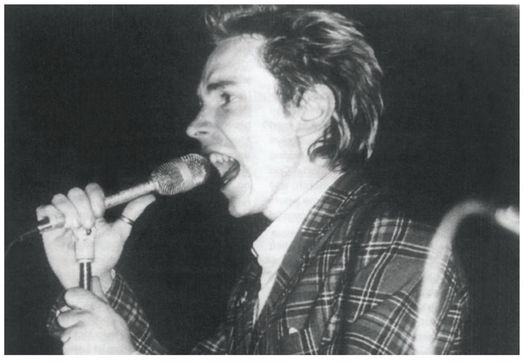

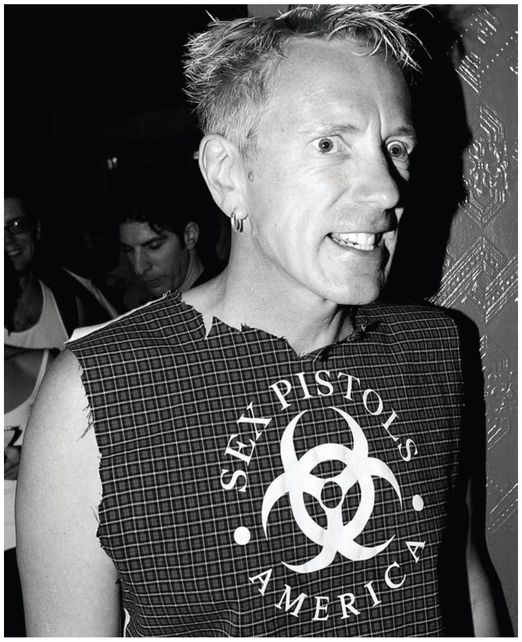

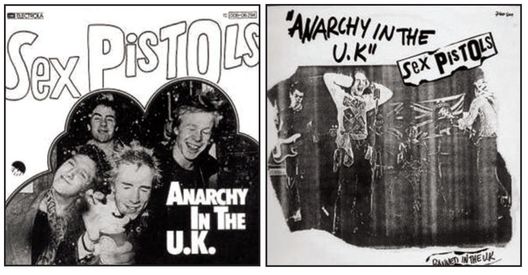

As the world knows, Johnny Rotten, born John Lydon in 1956, first came to public attention as a member of the Sex Pistols, a band that emerged out of the milieu that had grown up around Sex, a London boutique run by the designers Malcolm McLaren, the band’s manager, and Vivienne Westwood. First conceived as a walking poster for the shop, the so-called punk group made its first appearances in late 1975. In a series of incendiary singles released over the next two years, from ‘Anarchy In The UK’ to ‘God Save The Queen’ to ‘Holidays in the Sun’, the band, with Rotten at the front and McLaren in the wings, took on the whole of the social order: pop music and the Royal Family, God and the state, the imperial past and the impoverished future. Rotten left the band after its last show on its sole American tour, in January 1978; while legally enjoined from the use of his chosen name he reverted to his given name for the formation later that year of Public Image Ltd., or PiL, which he insisted was ‘a company, not a band’. With its line up of musicians shifting, PiL performed and recorded into the 1990s. In 1996 and 2003 the Sex Pistols reformed for reunion tours. Seemingly desperate to remain in the public eye even if no longer able to catch the public ear, from 1999 through 2005 Rotten made forays into Internet radio (Rotten Radio), television (Rotten TV, John Lydon Goes Ape, John Lydon’s Shark Attack), the nature travelogue (John Lydon’s Megabugs), What Makes Britain Great – a series made with the Belgian historian Marc Reynebeau – and the reality show I’m A Celebrity – Get Me Out of Here!. In 2006, as if from the alley running behind the temple of culture, Rotten recorded a podcast for ‘AngloMania: Tradition and Transgression in British Fashion,’ an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York that celebrated the work of Vivenne Westwood, who since her days at Sex had become the most celebrated English designer of her time.

At The Party

At the party to mark the opening of ‘AngloMania’, as the New York Times gleefully reported, the likes of Charlize Theron, Charlotte Gainsbourg, Tom Ford, Drew Barrymore, Gemma Ward, Sarah Jessica Parker, Minuccia Prada, Julian Schnabel, Ralph Fiennes, Sienna Miller, John Galliano, Jonathan Rhys Meyers, Lily Cole, Alexander McQueen and Lindsay Lohan, not to mention Vogue editor Anna Wintour, the Duke of Devonshire and Vivenne Westwood herself, had no need to notice Johnny Rotten, even if everyone did. ‘When John Lydon, the former Sex Pistol known as Johnny Rotten, found his seat – the last at a long table and arguably the least desirable in the highly orchestrated seating plan – he was visibly upset,’ Cathy Horyn reported. ‘Which was funny’ (by which Horyn clearly meant, ‘amusing’): ‘You wouldn’t expect a punk to attend a society dinner, much less be aggrieved by his placement. Mr. Rotten stormed out twice, cursing museum workers. Eventually he took his seat.’ ‘I’m Johnny Rotten,’ Eric Wilson quoted him saying, ‘and nobody here knows me.’ As it should be, Wilson was saying, for an ‘oafish,’ 50-year-old man ‘who wobbled around the edges of the party,’ ‘responding to anyone who ventured an introduction with unpleasantness that bordered on the wrong side of rude.’ ‘Ta-ta,’ Wilson said.

It was really too perfect. For Horyn and Wilson, it may have been a mere flick of the NOKD wrist, but the business of fashion writers is telling their readers what they want to hear, and what their readers want to hear is that just as they are blissfully inferior to certain orders of humanity, they are just as certainly superior to others. It’s pure pleasure to be reminded of the compromises and failures of those whom you might have once admired, or feared, especially when the compromises and failures of others – with the has-been stripped naked in the public square, or the museum ballroom that stands in for it – are so much more spectacularly degraded than one’s own.

Out The Door

It’s unclear what compromises Johnny Rotten has made, under whatever name, at any time or place. In press conferences and one-to-one interviews, on stage and on record, before the camera or behind the microphone, from 1976 to the present day he has been intransigent, mocking, cruel, unforgiving, and unwilling to concede an inch. ‘They can’t get rid of us. And there’s a reason for that. It’s truth. You can’t hide truth. You can’t manipulate it. You can slag us down, but you’d be wrong. I’ve not put a word out wrong, not ever,’ Rotten said in 2003, when the Billboard interviewer Scott Martens challenged him on the legitimacy of one more Sex Pistols trip around the block.

People who refuse to admit mistakes – and in a philosophical sense, not out of a sense of privilege, protection, and entitlement – can be very scary. They don’t speak ordinary language. You can’t tell if what they’re offering you is argument or noise, a challenge or a shield: simple meanness, the reflexes of a bully, and the terror of being exposed for nothing more, or the mental agility of someone who was out the door before you walked into the room.

In 1979

In 1979 PiL released its second album, Metal Box. Like so much of its a-company-not-a-band rhetoric – the band was, then, Lydon, the guitarist Keith Levene, the bassist Jah Wobble, and drummers – the object seemed more concept than anything else: three 12” 45s (for the depth of sound only a 45 could provide, one was told) packed in a film canister. (Today, as a single CD in a tin can, the packaging is if even more conceptual: a pill box.) The late music critic Robert Palmer wrote of seeing the thing in the window of a record store, stopping, staring, ‘wondering what it was’ – and what, he didn’t have to say, such a thing could sound like, if only to live up to the unlikeliness of what it looked like.

Today, more than a quarter century later, it sounds like music – or an argument about music, or about how to walk down the street – that no one has even tried to catch up to, PiL included, save for stray tracks over the years and the 1980 live album Paris au Printemps, credited to Image Publique S.A., which took the signal Metal Box numbers ‘Chant’ and ‘Poptones’ to places they’d never been before. Not long ago I walked into Amoeba Records in Berkeley – a huge, independent store with new and used CDs and vinyl, DVDs and videos – and caught the Metal Box opener ‘Albatross’ in the air. It cut through the somewhat depressed atmosphere of the place – the oppression of too many products. It still didn’t fit. It came from somewhere else – not that you’d necessarily want to go there.

This was drone music. You could imagine that for all the hate the Sex Pistols threw The Beatles’ way it all came out of that last, long chord at the end of ‘A Day In The Life’. If you listened long enough, hard enough, or casually enough to Metal Box – not listening at all, ignoring the record when it was on, until a scratch of melody or a vocal inflection or a word or a phrase that seemed to come out of nowhere but fit perfectly (‘Still the spirit of ’68’) snuck up behind you – you began to hear themes, cries, distortions, chords, choruses, words, and sound effects that made you wonder if they were less present in the grooves than suggested by what was. It was a miasma of doubt, refusal, arrogance, and utter vulnerability, with Lydon chanting, not singing, stretching out his vowels until his voice lost any ordinary character, appearing in the sound as himself a distortion, someone who sang from something other than an ordinary body. If the music was about walking down the street, if you saw the man inside of it coming, would you turn around and walk the other way, cross the street, or pass by under his gaze, sneaking just a glance to see if his eyes were as bottomless as his voice implied they had to be?

As Robert Palmer said once he’d gone into the record store, bought the set, taken it home, shaken the discs out of their can (they were packed so tightly you couldn’t prize them out, you had to turn the canister upside down and shake it, with the result that the discs fell onto each other, scratching themselves), and put them on, it was perhaps the most extreme version of ‘art for art’s sake’ pop music had ever produced. The music could sound that way because, to someone used to pop, it seemed so formal, so relentlessly focused on its own shape, on the generation of its own rules. And yet the last thing the music did was turn its back on the world. It was a version of it: one that said, finally, that nothing you wanted would come to you as you wished. The slow, dragged out pace of the songs and the beaten, punished sound of the singer said there was nothing new under the sun, but inside the music, the idea itself felt new, and liberating.

Bad Conscience

The man singing inside the songs on Metal Box is a man with a bad conscience. He’s filled with guilt, disgust, self-loathing. The sight of other people fills him with revulsion; the sight of himself in a store window as he passes by is even worse. But what on Metal Box is a kind of art statement, or a dramatic role, is really the role Johnny Rotten, or John Lydon, has played from the beginning, and is playing now.

In Colin B. Morton and Chuck Death’s comic strip ‘Great Pop Things’, the leitmotif of which involves the pop dream of changing the world (Eric Clapton: ‘Tried to Change the World by Being God’; Abba: ‘Tried to Change the World by Snogging Other People Behind Each Other’s Backs in Public’), Johnny Rotten appears in many forms, most effectively as a compost pile, if a compost pile could be made of corroding safety pins, a rotting t-shirt, filthy spiked hair, and bleeding sores. In ‘The Adam Ant Story’, as Adam (‘He Tried to Change the World by Dressing Up as an Ant’) muses over band names, Rotten looms over him like the Elephant Man, screaming: “GO AWAY I DON’T LIKE ANY OF YOU, MAAAN!” A ‘Where Are They Now?’ feature from the 1977 Liverpool punk fanzine The Assassin reaches into the great no-future to catch up with the erstwhile Antichrist: ‘It all went horribly wrong,’ he says. ‘I burned up all my hate.’ But that never happened – or, if it did, John Lydon never admitted it.

As time went on, he insisted with greater and greater vehemence on his place in history – or, to put it more precisely, on what he’d done, and why the world had never been the same since. Time and again, as he ran through the litany, it came off not as the pathetic boast of a bum on the street but a maddened, patient argument less with people than with life: an argument against the fact that people will do almost anything to deny that the world can change.

Changing The World

The pop critic Neva Chonin was reviewing a 2003 Sex Pistols show; the headline in the San Francisco Chronicle read ‘Sex Pistols’ Lydon tries, but can’t revive rage on reunion tour at Warfield.’ ‘What can you say,’ Chonin said, ‘about a 25-year-old legend that died? That it changed your life, changed music history, and hated The Beatles?’

As a bad conscience, as someone who would never say yes, Johnny Rotten inspired millions and influenced only Richard Butler. Colin B. Morton and Chuck Death, for their strip celebrating the Sex Pistols 1996 reunion tour (‘They Tried to Change the World Again 20 Years After They Had First Changed the World’), brought Princess Di into the band, and it made perfect sense: why wouldn’t she have a Johnny Rotten poster on her bedroom wall, as a talisman that she too could say no, just as Daniel Day Lewis’s Gerry Conlon has a Johnny Rotten poster in his prison cell in In the Name Of The Father? To one person the picture promises that she too can say no; to another, a man whose own voice is imprisoned, it says that there is someone who speaks for him. Princess Di is having the time of her life in her ‘Never Trust a Hippie’ t-shirt, spewing her lines about the hippie she married: ‘What is a man what has he got two great big ears and he talks to pot plantsaah!’ Gerry Conlon was out by 1996, forty-one when John Lydon was ‘fat, forty, and back’: didn’t he belong in the band, too? Or was he already in it?

Sinéad O’Connor always was, and never more so than on 3 October 1992, for her famous appearance on Saturday Night Live. There she was, in a long formal gown, with a Star of David necklace and a nose stud, her head shaved, chanting her rewrite of Bob Marley’s ‘War’ unaccompanied, her face shifting by imperceptible degrees from saint to thug, rat to Hedy Lamarr. Then for the last line she produced a picture of Pope John Paul II, ripped it to pieces, and shouted: ‘Fight the real enemy!’ It was her version of ‘Anarchy In The UK’, her acting out of the challenge John Lydon had issued to whoever might have the strength to take it up. Like ‘Anarchy In The UK’ – with the names of terrorist organizations reeling off the radio as if the newsreader were announcing his membership in each group – it was a classic media shock. And it was more. When someone acts as a bad conscience, that means he or she acts as yours. Even if you were with O’Connor all the way – after the fact, after that strange, suggestive tearing sound of switch, switch, switch came over the air, live on the East Coast, uncensored as the signal passed through the Midwest to the mountain states to the West Coast – you had to realise that someone in this intransigent would, like Johnny Rotten, sooner or later put you on the other side. And it was more than that. If what O’Connor did seems like a cheap stunt, self-aggrandising, a set-up, ask yourself this: given the chance to say what I want to the whole country, would I have the nerve? That was the question Johnny Rotten asked from the first moment his voice was heard in public.

Sinead O’Connor

God Save The Queen

On his 2006 podcast for ‘AngloMania’, Johnny Rotten read out the lyrics of ‘God Save The Queen’ as a manifesto, or an illegal broadcast: ‘Common sense from a common man.’ He was too modest: common sense, maybe, but from an uncommon man. No one else would have written what he wrote, or said what he said in the words that he found. ‘God save history/ God save your mad parade, ’ with the r’s in parade clattering like a stick run across a picket fence? He read with evident satisfaction; you could hear him shuffling the pages. ‘I come from a time,’ he said, ‘when it was treason, to discuss the monarchy, in any other way, other than complete and total idolatry. I changed that. The Sex Pistols changed that. We changed that. Now you change that.’ He still knew how to do it, he had told Todd Martens in 2003. He’d been trumpeting how the Sex Pistols were still on their own, still scorned, touring without a label or corporate support, ‘chipping away at the system bit by bit in as many ways as possible.’ ‘Aside from touring without a label,’ Martens said, ‘what else are you doing to chip away at the system?’ ‘I’m going to Baghdad,’ Rotten said. ‘The Sex Pistols will play Baghdad. You’re offering them democracy; well, let’s give it to them in the ultimate extreme.’ Martens was not impressed. ‘Wanting to play Baghdad certainly makes for a good soundbite,’ he said, “but how serious are you to see it through?’ ‘I’m deadly serious,’ Rotten said. ‘The show will be free of charge. It would be mean-spirited to be charging them US dollars. I will do it. I see no reason not to. They could use a good bleeding view of how the world is.’ ‘With all the chaos in Baghdad, aren’t they getting that view now? How would a Sex Pistols concert show them the truth about democracy?’

And that, you can imagine as you read this exchange, that was the opening John Lydon had been waiting for. ‘How can you even ask that to the man who wrote ‘Anarchy In The UK’?’

The Story Untold

You can laugh; as anyone who cares knows, the Sex Pistols did not play Baghdad. Or you can listen, to the way Johnny Rotten has chosen his words over these many years, and know what he would say next: Not yet. That war isn’t going away any time soon. Nor am I.

© Greil Marcus 2006

Greil Marcus

American musicologist and scholar Greil Marcus is the author of 1992’s In The Fascist Bathroom (Harvard University Press, 1993), a compendium of his essays on Punk. He has written about music since the start of his career in the late 1960s, when he joined the team of the newly created Rolling Stone magazine. Through the 1970s he continued there, while also contributing to the seminal Creem and Village Voice journals. In 1989 he authored Lipstick Traces: A Secret History Of The 20th Century (Harvard University Press, 1990 / Faber & Faber, 1992) in which he forged a link between the Sex Pistols and the Dadaist art movement.

He is also the brains behind 1991’s Dead Elvis (Doubleday) a collection of writings on cultural obsession. His most acclaimed work however remains Mystery Train ( Penguin, 1991 / Faber & Faber, 2005) his stunning study of American music and culture.