In With the In Crowd: The View From Under The Floorboards

Icon n: an image, a representation, a simile or symbol, a representation of a sacred personage.

Iconoclast n: an image breaker, one who seeks to overthrow traditional popular ideas or institutions.

You can become an icon these days by showing your cervix to 10 million people or surviving the ups and downs of the entertainment business for so long they don’t know how else to bill you when you won’t go away. To be an iconoclast is to be in another kind of lineage, a lineage with an indefinite shelf life. You can’t make an iconoclast with new clothes and a bit of second hand philosophy. Fully realized, iconoclasts have no need to re-invent themselves. They need only to never flinch. Clearly, John Lydon is an iconoclast.

The celebration of Pop Modernism that was Bowie, Roxy and Glam Rock had crumbled under power cuts, the three-day week, 14% unemployment, the IRA’s strategic decision to take their battlefront to the mainland et al. Everyone was so poor that it all just looked tatty. By this time mainstream music was so naff that it was a relief to just ignore it. The first wave of Punk rose up stripped back to basics. Sinead O’Connor summed up part of the mindset later when she said, ‘I do not want what I haven’t got.’ There was finally no shame to ‘not having’. That hardness and focused inflexibility was there to enforce a level game field. However, Punk’s undertow was the Fin de siècle sensibility of what would become the New Romantics, a bounce back to proportionally based beauty, glamour, melody and the tyranny of hairdressers. Elements of both these styles existed at the same time in London, vying for dominance, they always do. To claim invention for such a natural phenomenon is like claiming control of the weather.

I had been in London since 1970. To start with I had lived in the clique around Roxy Music. The first songs I wrote were done in Eno’s little closet sized home studio. I recorded ‘with lack of craft’ with Brian Eno on The Seven Deadly Finns and Taking Tiger Mountain (that’s me in ‘Back In Judy’s Jungle’) and had been in a performance arts group with a few of the crowd that went to Reading College with him. I lived in Chelsea, then North London and worked as a resident stylist for a studio in the old Covent Garden. I sensed that there was no chance of working as a recording artist if I was unwilling to accept the limited female role on offer to girls (before Punk). But I thought for just a minute there was a way around it when John Cale hired me to work on his album Fear. While working in the studio, John became a friend whom I still value very highly, but unfortunately, artistically with John, it was still the same dead zone for girls. I don’t play tambourine and I’m not a chick back-up singer. At street level, something new was just rumbling that would be later known as Punk. I defected to this new wide-open DIY band movement, sold all my Roxy style clothes to a second hand shop in Covent Garden, and moved down by the gas works, off the New King’s Road. I never looked back. During the day I ran around town with Chrissie Hynde and at night I worked, writing with Patti Palladin, for our group Snatch, splicing together bulk erased 1/4” tape on her Teac and making loops running around glass milk bottles. We learned about studio sound and equipment quality in that room. Patti still has a very basic amp housed in a blue metal box the size of a pack of fags that was bought for a tenner on Denmark Street. It was called an AX AMP. It doesn’t even have an off and on switch but you get the dirtiest guitar sound ever jacking into it and it makes an excellent feed back circuit. We recorded everything ‘hot’ and sang in unison. If our roots were in American ‘girl groups’, self-production and the home studio was our way to break free. It was what made us unique and included in the first wave of punk.

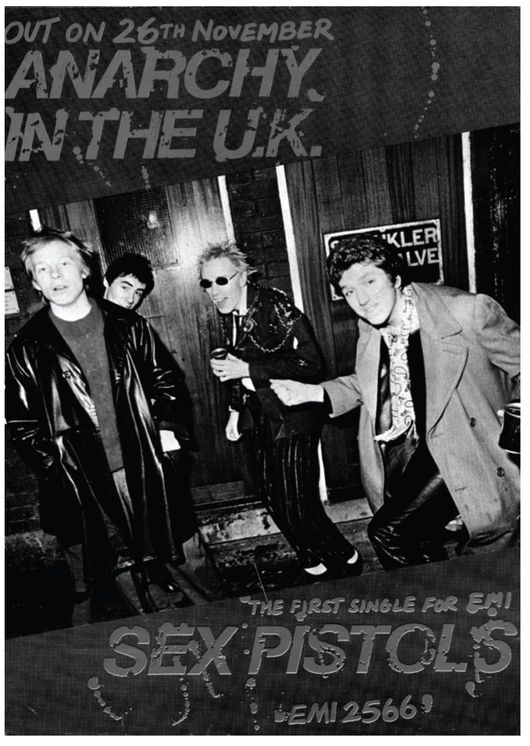

My dole check was a bit better than most because I had already worked at a reasonable wage. In spite of having a continual cold and never enough money to even pay on the bus, I remember this period as one with a lot of joyful moments. The Snatch single Stanley b/w IRT came out the week before The Damned’s first single and hearing it played for the first time over the sound system at the Roxy was one of life’s great moments. My memories of the whole Punk period are colored by the fact I’m female. I remember time as a textural field in which the details are more important because they make it real. The ‘personal and emotional’ tend to chart punk more precisely than the ‘timeline’ and because the days were far from routine it was hard to know what was important while it was happening. So far, other than Caroline Coon’s 1988: The New Wave Punk Rock Explosion which anticipates the importance of Punk, all of the numerous histories are written by men. Context is everything; cultural events overlap. For instance, I don’t remember meeting people usually, but I clearly knew Viv Westwood before her store was the Sex shop because I remember wearing a pair of faux leather Oxford bags from Let It Rock that she had given me when I was directing the building of the indoor beach, holding a megaphone from the mezzanine level of the photo studio. The same trousers showed up on John Cale in the photo on the cover of his Helen Of Troy LP. I don’t remember the moment I met Johnny Rotten either. It was most likely in the Sex shop at about the same time I met Steve Jones and Marco Pirroni. I do remember that Johnny rated Captain Beefheart and early 70’s German stuff. I’d reviewed Magma for NME and was surprised that his taste, like mine, went beyond the VU, Iggy and the usual bands mentioned as influences.

Punk is an ongoing guerrilla war for the mass mind, the movement in mid to late 70s Britain was just a particularly colorful chapter. It is a war that can never reach a final peace. There is always part of the mind that loves revolution. My membership of the Roxy club, London’s main Punk venue during 1977, expired on the thirty-first of December that year. For me that was the end of the era. For almost 30 years I haven’t been able write about it; I couldn’t even think about it without a rush of rage that I was unable to express without crying. Not that crying discredits the truth of what you’ve said, but I didn’t want to speak until I had some understanding of why this area of thought was so toxic. In general I’m emotionally contained, but I still feel very strongly about the rights and wrongs in this period of my life. I remain unconvinced that there is any part of the music business that should be salvaged and carried into the 21st century. It’s had a sixty-year run yet remains a vehicle for forty-year olds to take advantage of twenty-year olds. The organization seems more civilized than child prostitution in Asia but the intent is not. Even now the industry continues to blame its problems on ‘new technology’ rather than owning up to ‘repellent practices.’

As a kid, whenever I shouted, ‘Just leave me alone’ my aunt would say, ‘Can’t a cat look at the queen?’ When ‘Anarchy In The UK’ was followed by ‘God Save The Queen’, thereby putting the Pistols’ music and image into the public domain, imagine how it must have felt for John Lydon when the Queen knew who the cat was. John Cale, who didn’t approve of the Pistols’ attack on the Royals, said to me, ‘The Queen is the living embodiment of the rules by which gentlemen do business’. It was likely a creed he had grown up with, but now it was a conversation stopper. I’m no ardent anti-royalist - I was born in a country where lawyers and the heirs of robber barons run the government into the ground to compound profit at the expense of the social contract - and the notion of a person being trained from birth for ‘the job’ doesn’t particularly offend me, but I do stress the Crown’s obligation to the cat. The degree of public allegiance is directly proportional to the royal embodiment of commonly agreed ethics. You get the training and the castles but you also get dragged down and replaced when you become corrupt by association. And the agreed ethics are constantly to be challenged by people who think like John Lydon. That’s the deal, whether you need protection dodging the bullet or the ballot - and there are very few ‘gentlemen’ who you can safely turn to in business.

Stop anyone on the street and say, ‘Name a Punk’ and they will most likely say ‘Johnny Rotten’ or possibly ‘Sid Vicious’. To look at it all through Lydon is to regard the glass as half full. There was always something hopeful in John’s vision; an insistence that wrong might be righted if you don’t cave in. As the Pistols’ lyricist, he wrote out universal thoughts in a very local language. There was always a pecking order in a Lord Of The Flies sort of way to London punk; if you could gather a hundred or so people who lived through it as part of the ‘inner circle’, they will almost certainly agree that John Lydon stood front and centre because he was the ‘flack-catcher’ as much as Sid was the ‘sacrifice’.

There was a lot going on. We had no time to do anything but live in the present. We all lived so closely that a ‘bleed through’ of memories was inevitable. There are several good books on the punk era, by people with more feel for research than interpretation. These state just the bare bones of fact; I refer to them too and I was there, but the way the dots of fact connect when you include the memories of more people is something else. Ultimately this is more interesting to me. For instance, I’ve read quotes from Chrissie Hynde saying she walked with Rotten to his first gig; but I have my own memories of walking him to the very same event. These are synaptic clips of traipsing small, dark, wet street gutters in Soho with Johnny in front of me; in this memory I am sensing his quiet agitation. No one spoke. There was no costume; he went from the gutters to the stage without changing. I don’t remember Chrissie being with us, but then she obviously doesn’t remember me being there. However, Chrissie Hynde and I were together a lot of the time; maybe we were both there or maybe the boundaries of memory between us have blurred. I can picture Mick Jones in the very small audience even though I didn’t know him then. In this memory grab, he has long hair and a long white scarf. The drummer for The Damned, Rat Scabies, has said, ‘Mick looked like he was in Mott the Hoople’. His memory supports mine of the white scarf and the style. In the details, all of us are present in that place and hour. There is architecture, a multi-sided truth that can only be assembled with the bits we each recall. Truth may not go forth naked but it is relentlessly buoyant and certainly makes more sense when you think it through. It is there in a composite of the details that fill in the space between islands of research. Even though I could read what was happening as it was going down, I didn’t have time to catch the implications, to string it together; not until now.

Very few of us were known by the names on our birth certificates; it feels endearing to remember someone as ‘Rotten’ even if I am now to be confronted with a grown man in his 50s. We were tribal but not along bloodlines or back-stories. There was a subtle linkage by being from a particular location like Bromley or Forest Hill and hitting London at that angle, although I’m not familiar enough with these small enclaves to interpret the fine points. On that level, I still belong to the group of four ‘Yanks’ - Chrissie Hynde; my partner in Snatch, Patti Palladin; photographer Kate Simon and me. I knew Kate from Chelsea in the early 70s. Palladin I met over a long distance phone call when she agreed to bring me some trousers from a New York designer I’d liked since Doll days. Chrissie and I met when she showed up at Brian Eno’s to interview him for NME in connection with the Here Come The Warm Jets album. The number of Yanks in London expanded when the Heartbreakers, Nancy Spungen, and Jayne County arrived. Because the United States is so large - the entire landmass of the United Kingdom fits into the state of Florida - there was a curious crew formed by cobbling us all in together, but we were not sharing any regional sensibility. By virtue of us each being a minimum 5,000 miles away from our places of birth, we were also not as malleable. Any of the Yanks knew how to source whatever they wanted, wherever they were. I had been on my own all over the world since I was 16. We could never become the kind of pets the music business wanted unless we were strung out and sleepwalking. Malcolm McLaren’s idea of social revolution didn’t fly because all of the Yanks had already pulled time in Paris and had witnessed the difference between French words and French deeds.

Johnny was never ageist and even before he had much mileage himself it was clear that he had no fear of experience. John chose Nora as his partner. He chose, not some punky version of a “dolly bird”, but rather a stunning, athletic looking, tall, blonde, European woman who spoke several languages, did not need financial support and was impervious to the petty imbroglios of the punk crowd. It was an unusual, somewhat daring choice for an 18-year-old boy from North London. Nora was older than John, and her daughter Ari is one of his closest friends. Nora placed herself between The Slits and the worst abuses offered by the record business and stood strong with Rotten no matter what. Thirty years later they are still together, though they were never the kind of couple that the press had any idea what to do with. The media likes ‘young’, ‘doomed’, and ‘clichéd’ couples for ‘puff pieces’. Nora and Johnny were way more complicated than that. I remember being in Nora’s car with John riding shotgun. She was driving fast to get back to John’s flat to go to the loo. We got there and John was pretending to have lost the keys. It was a playful torture. Sort of odd to be included as a witness, but I don’t think anyone would be dumb enough to be lured into badmouthing either of them. They would certainly turn on a common enemy; that’s how the relationship worked.

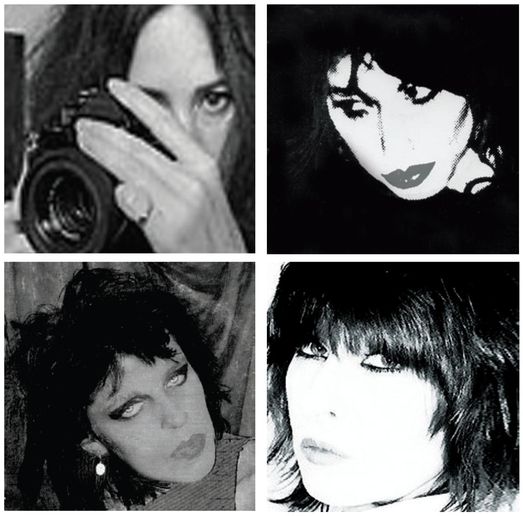

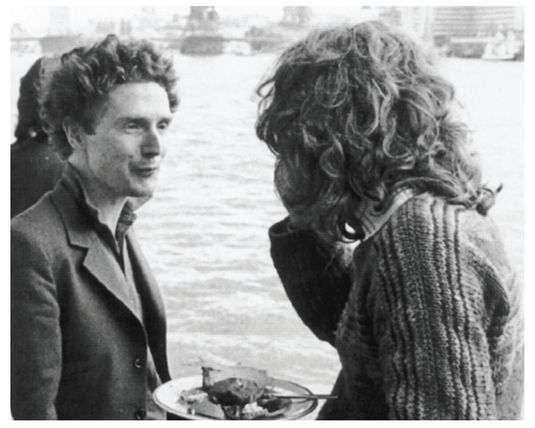

‘Four Yanks’ - clockwise from top left -

Kate Simon, Patti Palladin, Chrissie Hynde, Judy Nylon

That present seemed then like a vast expanse of wet grey dead time populated with home done haircuts and faded black rags, jazzed up with a jangle of chains. But we were energized, even in repose. Mostly I remember walking; walking to get somewhere or walking for entertainment; hanging out at record stalls or waffling for hours over a pint in one of three or four boozers - in Chelsea, Soho or Portobello Road. Rotten could hang around doing nothing like nobody else. He was not the life and soul of the party, but he was wide open and he was fun. I have a soft, tender memory of Lydon, John Gray, Patti Palladin and myself dancing on the backbeat, reggae booming in Patti’s tiny flat. The space was only about 10’ square and dark for a lack of electrical outlets; a run down dollhouse in a mews lit at street level with a single light on wet cobblestone. It was like an empty movie set once the garage downstairs locked up at 6pm. The analog home studio was stacked around the room and a spaghetti ball of cords ran behind everything. It was a punk clubhouse, one of a few; we all made the rounds to each of them. To this day I remember the location of every cigarette machine in a one-mile radius of that mews. John and whomever he was running with functioned like an off-stage clack, providing a distracting and on-going commentary. It was smart and droll, like Beckett; it filled in the hours of nothing to do, while holding endless cups of tea.

As with anyone and virtually everyone who was informed as events unfolded in the Lydon Vs. McLaren saga, I am firmly with Lydon on all counts. John is the artist here; manipulating other people is not an art; selling is not an art - whether it’s snake oil or skinny rubber t-shirts - it’s a knack; at best, a skill; useful for the artist to be aware of, but the notion of the deal as ‘art’ I find ludicrous. It can never be said too often that if Malcolm was the artist, he could have fronted the Sex Pistols.

I would love to see John Lydon turn his hand to all the things that catch his interest; he’s game and always engaging. His recent I’m A Celebrity, Get Me Out Of Here! and Megabugs television series suggests he’s more open than ever to give things a ‘go’ - but battling with Malcolm McLaren, long before any issues were dragged through the courts, was surely exhausting. Being deeply involved with someone, professionally and financially, whom you don’t trust an inch, fearing to even blink in their presence, cuts seriously into your time and quality of creative daydreaming. If he has stepped back, away from the fray, to ride a bicycle along beach roads, it is understandable. He’s been through the machine.

Like John Lydon, I am very familiar with the ‘No Dogs, No Blacks, No Irish’ signage. They had those signs in Boston too. Being of Irish descent in mid-70s London was not an advantage for anyone, but back then very few people in London thought of Americans as having an underlying ethnic identity, so I never mentioned it. Lydon and I share a background in the Irish Diaspora. I’m also aware his, like mine, traces back to Galway. Undoubtedly we were told the same famine stories to keep the rage warm. There is no emotional compensation to be had in being at the survival end of your DNA chain. Almost everyone in Punk was descended, within one or two generations, from some social injustice somewhere. A sense of such probably explains why waves of Punk keep coming, even 30 years on, as yet there is no shortage of social injustice. Sub-Saharan Punk will be an exquisite confection of disenfranchised anger, something to really look forward to. Punk is always the gristle that doesn’t break down in the crucible of pop culture.

I still do not really value anything that is decided by committee; maybe that’s Punk. For the first wave, hitting the shores of being 50-plus, it’s not the end but rather the second act. ‘Refine not Recant’ is a good way to proceed. Since Punk I’ve come to understand the power of not having secrets. Privacy in the 21st century has certainly been revealed to be as much a wishful human construct as safety. One is never ‘safe’. If you run and hide you will be chased and hunted down. Punk even then was a para-dynamic model of a just society. In Punk everything happened late at night among children. You subscribed to a code of morality where a fall from grace is guaranteed a swift punishment and exile. In London, at least, Punk was predominately vegetarian, humanist, but also survived only by the fittest. It was violent; it had to be. I have no patience for the notion of ‘street cred’. Because my own background was grim enough that my street credibility was never in doubt, I feel obligated to be the one to insist that England works best without false class wars. Gutter roots don’t make you special any more than upper class roots do; you just have different skill sets. If you are street smart, you protect others. If your luck was wealth, you pick up the tab or buy time. There was a lot more diversity in Punk than the history you’ve heard would lead you to believe; everyone had inherited both a destiny and demons of diverse kinds. I believe more ‘Punk ethos’ has been scattered throughout the world than is immediately apparent.

The whole Punk-Reggae sensibility was unique to the British strand of the form. This commanded the bridge leading a multiracial generation from analog to digital. Making sure that everyone has web access worldwide is what is crucial now. Reggae’s influence on humanizing punk is well known, but it is only now that Punk’s influence of strengthening Reggae is becoming clearer. We were never media naive. For those of us who rode the first wave, there was both the exhilaration of being on camera in a televised social war and the discomfort of being under a microscope, handled with tweezers in the hands of the enemy. We were studied like fleas because we did not own power outside of what destruction we were capable of doing. The feeling was that you were in the center of a very small world that mattered, where events were unfolding faster than they could be analyzed or spun. We hardly paid attention to the feedback outside ourselves and were in fact purposefully uncooperative in a world where others had press agents and queued up to get 15 minutes of strobe light bounced off their teeth. Our poverty was somewhat shocking to rock stars of an earlier era that had aspired to never having to do things for themselves. However, simply put, if you decline to make money off the backs of others, there is less money to be had in ‘immediate reward’, but in a long artistic career of slow accumulation, there is always enough.

To this day there are not many intimate photographs of the period. What you have seen are nearly all taken on the street or at gigs. The quality of what has emerged is mostly low because it was either commissioned by the record companies or limited to band shots and people sucking microphones on stage. There is very little information in the background of the picture. There are many images yet to come, cannibalized from sequential stills or digitally reconstructed into that ‘as yet un-named media’ (a phrase everyone crosses out in contracts). All new technology is magic (with all the inherent cargo cults) until you understand it. There are probably plenty of images still trapped in boxes on closet shelves, archives, or in garages in the countryside, because people fear the cropping or the cannibalization of their personal memory. My guess is that there will be no deathbed confessions and no stories told for free to some young magazine hack. We’ve all rolled over into the age of blogging, self-archiving, citizen reporters or whatever you want to call it; the public does not automatically get to know everything. Punk reserves the right to be unreasonable ‘in perpetuity’. It is not an end game, no one cares about ‘putting the record straight’. Since nobody else owned a camera, Don Letts’ work is what is known best right now and it can only be judged as a dog that sang the Marseillaise. Still, I don’t remember professional photographers other than Don and Kate Simon ever being welcome to hang out ‘off the record’ after the gigs and ligs.

There was no party line on the exclusion of press. There was only a self-protective stance to keep out anyone who would take advantage of you; but it wasn’t inflexible. If someone was old, fat, smart, rich, and powerful, it was up them to be irresistible company. I adored a few crankies who fitted that profile. Lydon was intuitive about who should be kept at arms length. You had to personally feel what was real; there was no guiding voice. Johnny didn’t really buy into agitprop revolution or the class struggle motif that was being foisted on Punk; Nora was hardly a waif. I suspect that it wasn’t a Lennon imagined working-class-hero that he wanted to be, but a classless hero in a world of equal access.

Don Letts

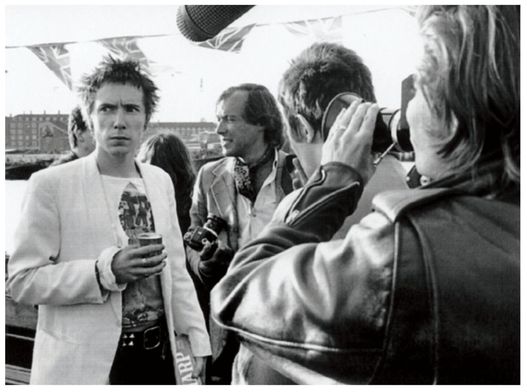

It was always hard to get a candid photograph of Lydon. He was aware of the camera and played it like a harp, even if he wasn’t looking to lens. I saw one picture of him glaring at Malcolm, who is clearly engaged in something else. It is a narrative staged with complete self-consciousness, to be enjoyed in print later. The only other person I can think of who could pull this off as well as Johnny, was Princess Diana.

This might be a good time to mention that the ‘who ripped who’s T-shirt first’ debate regarding timelines of London and New York punk, is absolute rubbish. Plane tickets were cheap and both Brits and Yanks moved back and forth. There was no nationally isolated development. At best you can say English language punk came first. American punk was not underpinned by any socio-political thought, which is what defined London punk more than clothes or songs. There is ultimately no point in a comparison made of apples and pears. Importing the Heartbreakers and Nancy Spungen into London was like exposing Native Americans to Europeans in the 17th century. Payback. The outcome was inevitable. The New York scene was infected with the same drug, race and gender issues that had seeded cultural failure over and over. Too many of its key figures had been close to the ‘skin trade’. This connection is part of a continuing American entertainment lineage running through the brothels, slavery, porn, mob influence, and so on; it still holds true. The Arts and Humanities are not highly valued by the American government. UK punks can be thankful that their government’s threadbare socialism at least allowed for squats and dole cheques – making the lure of the Earl’s Court rent boy circuit less inevitable.

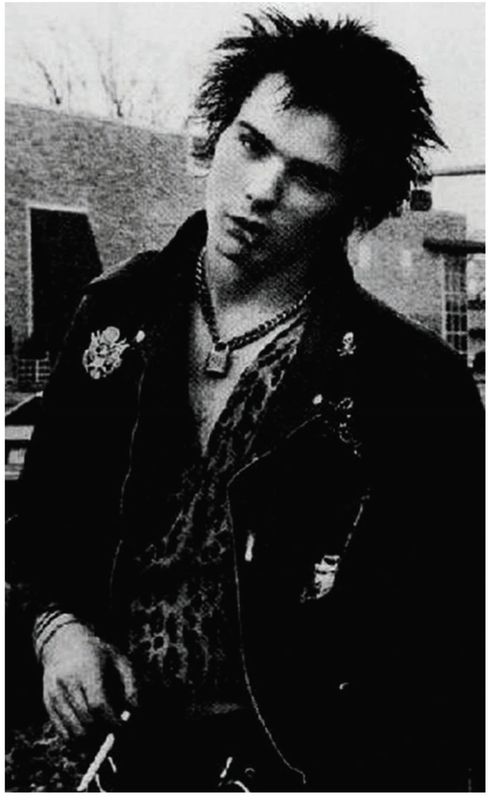

Before all that happened, the only Yanks most of the London crowd really knew well were Chrissie Hynde, Patti Palladin, Kate Simon and me. As different as we were from each other, we were all benevolent influences compared to what was to come. Even if drugs were certain to cull the herd, it was not possible to keep the punk era in a hot house with just beer, pot and a few uppers. Touring involves exposure to the rest of the world. By the time the first wave had disintegrated into drunks and junkies, the disappointment was palpable. It would be almost 15 years before I would run into Al-Anon theory and go back and re-read the photographs of John, as Sid was disappearing into heroin and inching closer and closer to death. Malcolm might have been too young himself to be fully aware that the interesting spectacle he was driving forward had consequences. Sid covered with blood, dazed and iconic, was matched by Johnny suffering, pinched and hateful. The Sex Pistols had become a living example of the family life Yeats described as ‘too much hatred, too little room’. The coming retribution after Sid’s death would fester with an Irish patience until John was old enough and strong enough to drag McLaren through the courts and out into the scrutiny of public opinion around the world. But look at the pictures; it started then. He was smoldering.

John revealed a less guarded self to women; he liked them. He liked female company. He set the tone of equality on the street. Punk, at street level, held total equality between males and females. Punk girls wore and said whatever they wanted. If they chose to walk around in garters, it was not an invitation to harass without expecting a violent response. Lydon was an equal opportunity offender, which is all women ever really asked for. He was very comfortable to be around; he didn’t seem to have anything to prove. Women were around him all the time but it wasn’t a harem, it was more like a palace guard. You’d be hard pressed to find a female who had been around him then that would testify against him today. The subsequent gender inequality in punk was injected by the record companies’ mistreatment of female artists.

Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood’s agenda of pandering to the carriage trade, with their expensive designer clothes, was pretty obvious early on. This crowd of malcontents was unlikely to go in for what Ian Dury called ‘new boots and panties’, with the same lust for ruffles and rollers as bands of the 60s had. Punk would not be bought off that easily. Palladin and I called out Vivienne’s intentions with a couplet in an early Snatch song, ‘Where’s that blond bitch, she’s always lookin’ a fight? Out selling her Mao T-shirts, 20 quid. Alright!’ She returned the shout with an inept fistfight at 10am one morning, and by the failed gesture of sending immigration to my door. There were a certain amount of Sex shop clothes circulating on the streets, but I never knew anyone who actually bought them. You wore some of it whenever it fell into your hands, just for a bit, and passed it along. Now, when you see the photographs, it is not obvious that you’re looking at different people in the same pair of trousers. The Pistols had the all the Sex shop gear they wanted, but the full retail price was allegedly deducted from their wages. I remember Jonesy stripping it off and throwing it in a bag, then getting on a pushbike after the gig and peddling away in a boiler suit. He looked like Robin Asquith in the 70s soft porn flick Confessions Of A Window Cleaner. A fluffy mohair sweater wasn’t worth being beaten up for when you were moving through enemy territory.

I was never personally convinced that Glitterbest (McLaren’s limited company through which he ‘managed’ the Pistols) hadn’t set the band up for a beating to keep them in line and provide an irresistible press op. There’s no loyalty when you’re just a product; the Sex shop had been called Let It Rock, flogging drape suits and brothel creepers to Teds under the same ownership, before Punk hit. It was just business. Johnny’s own style is always what he looked best in. Tricked out in rumpled suits and shredded sleeves with an old great coat thrown on top, that’s mostly how I remember him.

After he hit the papers, I don’t recall ever seeing him walk alone; Nora had a car; Palladin had a car, Viv Westwood had a car and Andy and Sue Czezowski (from the Roxy club) had a car. The rest of us kept street mufti fairly low key and home made. I never had much interest in bondage trousers; I’m not into having my knees tied together. I have got a slide of myself at the Roxy wearing one of the kiddy-porn Tees, but it must have been either Kate’s or Chrissie’s. I have never bought anything from Westwood and McLaren on principal.

The boat ride on the Thames was a pivotal event in the whole Sex Pistols saga. I didn’t even consider getting on a launch that I couldn’t get off for four hours, knowing Malcolm’s penchant for orchestrating outrage. I just looked at the pictures in the papers next morning, showing Viv fighting with the cops, and shrugged. It was all so predictable. Twenty years later, when it came up in conversation, Bertie Marshall (Berlin) said he wasn’t there either. Since then I have asked others out of curiosity. Kate Simon wasn’t on the boat. Patti Palladin and Chrissie Hynde weren’t. I’ve yet to ask anyone who said they were. I do wonder who exactly was afloat that day. Film extras? Immediate family? Industry stiffs? Members of the press, certainly. A saturated Richard Branson in all the photos. I’m guessing that Jubilee day 1977 was ironically when being in the band became a job. Johnny must have felt like he was cornered and they’d sent in the clowns!

‘Holidays In The Sun’, about slumming in the third world, has a sentiment I often think about even though I’ve never taken a holiday without work being involved. We all sensed we were on the threshold of first world implosion without exactly knowing what came next. It was a difficult idea to share; there was no language to discuss it openly, but there was a quality in what we had made that you knew couldn’t be for everyone, although everyone was encouraged to start a band. ‘Starting a band’ was the metaphor for changing yourself, like ‘hitting the road’ had been for the Beats. Malcolm successfully branded punk, tried to control it and inadvertently found that all the historical referencing in the world (remember, he wasn’t at the Paris riots, he just read the books) couldn’t make life into his private theatre. McClaren was always perfectly suited to work in advertising because ads are in memory ‘single frame’. Usually it’s the last frame in a commercial that is memorable. There is, inherently, an inability to control a social idea in an unfolding timeline. That sort of unfolding is best described as ‘enantiodroma’. This is a great word I picked up reading Bruce Sterling; it describes how something folds in on itself endlessly, like kneaded dough, or ribbon candy oozing out of a tube. Manipulation of the event can’t construct a ‘single frame final history’ anymore accurately than the point of view of a single eyewitness.

John Lydon’s birthday is the 31st of January; mine is on February 1st. It was the late night of his birthday and the early hour of mine when Sid Vicious died. That night was not about Sid coming to grief in a foreign land. Lydon knew everyone involved, I did too. The mule that brought the smack from England, the money that bought Sid’s hit and the guy who copped for him were all part of the London scene. You could say, ‘bad luck has a long reach’; or you just accept the idea that you cannot outrun the consequences of dumb decisions and unhealthy associations.

I’ve recently seen a picture of Sid Vicious and myself reprinted in a book on CBGB’s. I remember the moment. I remember letting photographer Joe Stephens know he could have one frame, because Sid was off duty. I felt protective of Sid, much as Johnny did. I also felt the frustration of being unable to stop the nightmare that Vicious was in. Like Lydon, I have a low flash-point and a sobering ability to avenge. It’s all part of the soldier-poet riff, that Irish thing. It was his rage that makes me remember him as angular. I wasn’t close enough to understand exactly what the point of the manipulation was to get Glen out of the band - since he could actually play - and replace him with Sid, who couldn’t. How did John imagine this would develop or was it a Glitterbest manipulation that blind-sided him?

I used to follow Formula One racing. I didn’t go to the track or anything, but I kept up with it in the papers, read a few books and looked at the cars when I could. I’ve found old scraps of newspaper in my diaries of the period. James Hunt was driving on the McClaren (no relation) team and Niki Lauder ran the Ferrari 312. I’d carefully note their qualifying times and their triumphs. In Formula One I think I’ve found the perfect metaphor to explain my subliminal feelings about the music business. The odds of surviving a driving career were stacked against you; about one out of five drivers crash resulting in death or permanent damage (or at least they did then). When you regularly hit 200mph you assume you have a dangerous job. When you pick up a guitar to make music you don’t think you are in much danger. Your chances of seeing a ripe old age if you are in a successful (or even just a well known) band are about the same as driving Formula One. This happens generation after generation and I don’t accept it can be explained as ‘only suicides, addicts and lunatics are drawn into making music’. The pressure to surface in grinding poverty, endless scrutiny, dashed hopes and legal manipulation is emotionally deforming. The final realization is that no matter how careful you are, you will be ripped off, cut down to size and shamed for stupidity. For most artists, each ‘pressing’ numbers just enough to make a chase through the courts with a 500-an-hour lawyer financially unproductive. If too much money (to hide) accrues on the books, the recording is licensed to the next label, where the routine (or some variation) starts all over again. Finding the royalties is a book keeping frustration that provokes self-medication in all types.

John Lydon’s duality of being a loner and a leader is oddly hypnotic. To engage with him makes you feel like you’re torturing him but the fact is he is holding you there. He is an authentic stage presence; power crackles off him like static electricity. I was spared all of the really bratty behavior, but the bristling energy he gives off when he’s put upon matches his mouth, and he could be cutting. There was not that same kind of charisma among the punk bands who kept touring, even if they became very professional by doing so. They’d forgotten the earlier tradition that most UK punk performers followed, meeting and interacting with their audience; an unheard of approach to live events prior to 1977. It’s a method that may return through necessity and prove to be the key to surviving, now that recordings are almost giveaways and the whole gig is a ‘meet and greet’.

I’ve seen several bands and performers lose themselves in the big blast of fame. It’s not pretty and most are never worth knowing again. There are probably those who feel this way about Lydon; he’s not wedded to the devil in the details, quite a bit of what he says is self-conflicting, but the larger gesture of what he is willing to stand for has never wavered. Even when he’s overwhelmed, he won’t back down. It’s a tendency to run screaming into certain death if you know it is the right thing. If you don’t see that, well, as Johnny is so fond of screaming, ‘You’re just not paying attention!’

Johnny has retained a love of echo throughout his career; sonic expansiveness, a landscape that acknowledges the void is with you always, not just when you’re stoned. His love of reggae was, if not instrumental, then certainly paramount in the music he produced post Pistols. In the early 80s, when the scene had moved on, the Jamaican habit of piling into the kitchen, passing the duchie and cooking up a stew with rice - resplendent with coconut - and with the music cranked was de rigeur. Before that, Punk cuisine was limited to bags of crisps, fish and chips, canned beans on toast and that foul concoction known as a chip buttie. For those who have never run into one, the ingredients are chips (fried potatos, for my fellow Yanks) between two slices of ‘mother’s pride’ (cheap nasty white bread) slathered with salad cream (a vinegary, low grade mayonnaise). The first time I was offered this delicacy was at The Slits’ hang out. We had all just gotten instruments which we’d no clue how to play. It was a room full of girls and unimaginable noise. I wanted so much to feel included that I closed my eyes and swallowed the whole thing in about five quick bites. The attempt to find a new ‘comfort food’ wasn’t very successful but the reverb that I associate with this period is still deeply imprinted.

Lydon gained much more creative bandwidth during PiL’s early phase. In a sense, Keith Levene fearlessly manifested the softer side of John, a quality burned out of him during the Pistols. PiL was essentially a great idea, whether or not it went as far as it could have. Personally, I think PiL has proven to be Lydon’s finest hour, most notably with the first and greatest line up, Levene’s contribution was as important as Lydon’s. They built new forms out of very different influences. If they’d had more time, less industry attention and hadn’t squabbled so much, they could have created another huge wave of music, and evolved into an umbrella organization to shelter other projects for a very long time. One problem I saw was the ongoing connection to Virgin. If it were resurrected today, PiL wouldn’t need record company involvement of any kind.

I had first meet Adrian Sherwood at Jeanette Lee’s, after Keith recommended his work to me. Adrian and I were able to develop a studio blend of content and form that sounded good to both of us. This collaboration produced the Pal Judy recordings, released as a - now impossible to find - LP in 1982. Many of the songs on Pal Judy had been toured and played live in NYC, where I was considered part of the ‘No Wave’ scene. I could only use a very basic Roland Space Echo on stage because it was all I could afford. Once recorded in London, the production we did brought these songs much closer to what John was up to in PiL. The stylistic connection has never been made, I feel, because my vocal performance was very American.

John Lydon’s experience of fame has been a weird one. He became a jackass magnet. Even people who should have known better (they were famous themselves), fawned and drooled. He’s been rewarded in money and access for the ‘news rape’ that comes with 30 years of media attention, but anyone he enjoyed hanging out with was certainly not going to endure this circus. Interesting people cross your path and move on when they suss the set-up. Hanging with animals is a solution. Some of the best relationships in my life have been with actual dogs. Taking the stewardship of the animal world, seriously, is the first baby step toward the love of humankind. I never had the sense that Lydon loved humankind per se. Maybe he’s doing better with animals.

The last time I saw John Lydon was in some stinky, sticky dump of a nightclub in New York, where he was obligated to promote his book. He was immediately surrounded by students (and I use the term loosely) who wanted him to sign their army jackets (these are possibly on eBay as I type). Nora complained, over some B-strain of disco inferno, she couldn’t get a fresh squeezed orange juice (seemingly unaware in this kind of joint you only drink from a sealed bottle). Lydon was bored, and no bloody wonder, I felt like I was talking to a fly trapped in amber.

I was delighted that, in early 2006, the Sex Pistols blew off going to their Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall Of Fame induction. The sort of fame they achieved was not something that the industry is ever going to be allowed to bestow and shape in its own image as a ‘billable’. It’s not all about entertainment, its control and business. Beside which, the satin baseball jackets they were handing out to inductees are surely red flags in front of a bull. They remind all of us of the tour jackets worn by the full figured A&R men with expense accounts and ponytails who populated the record industry in the 1970s.

An ending point here is that Punk launched an interesting set of people into an iconic continuum. It’s as ‘not over’ for them as it is ‘always new’ for the recently interested. When I first moved into my apartment in NYC, I used to watch John Cage come by and pick up the sculptor Louise Nevelson. They’d stroll around the neighborhood and then hang out on her rooftop, under a rattan pavilion she’d built. The rafters were hung with hundreds of bamboo wind chimes that made a particular clicking sound in the breeze. I could lie on my bed and see them framed in my window. She’d sit in one teak chair facing south, wearing a dark flowing kaftan and a Kelly green riding hat, looking like a Henry Moore sculpture. Cage sat in another chair facing her. Towards the end of his life I would describe Cage as a philosopher and a gardener more than a working composer. Forcing tulips in his refrigerator and composing music were meditations. They’re both gone now, they’re both remembered as a layer of New York City, the same way as John Lydon will always be a part of London. I think about Cage and Nevelson. I couldn’t hear them up there on the roof and I don’t get all I want from studying their work.

Intergenerational cooperation between artists is important; we didn’t get it, are we able to give it to people who come after us? The weirdest thing about being part of an idea that keeps coming, wave after wave, is the paralyzing replay effect. You can distract yourself with breeding or making money but there is as much need to change the way things play out at the end of your life as there was at the beginning. Yet the beginning is what is publicly replayed, over and over and over.

© Judy Nylon 2006

Judy Nylon

Brit-Punk insider Judy Nylon was born in Boston, Massachusetts, USA. An early friend and colleague of Brian Eno and occasional vocalist for John Cale (‘tis she who’s the subject of Eno’s ‘Back In Judy’s Jungle’, and who plays temptress on Cale’s ‘The Man Who Couldn’t Afford To Orgy’), Judy came to embrace punk as half of girl-duo Snatch with Patti Paladin. Part too of the ‘Yank girls in London’ quartet with Paladin, Chrissie Hynde and Kate Simon, Nylon took the ‘No-Wave’ route out of the style she was becoming tired of by 1978, and returned to New York, where no-wave was exploding.

She still lives in NYC and today is involved largely with art and writing. ‘Nylon’ was not a name adopted for its Punkish connotations, but had been a family nick-name, originally of her father’s, for years before the big event.