Goodbye and Hello: Holding Court In Troubled Times

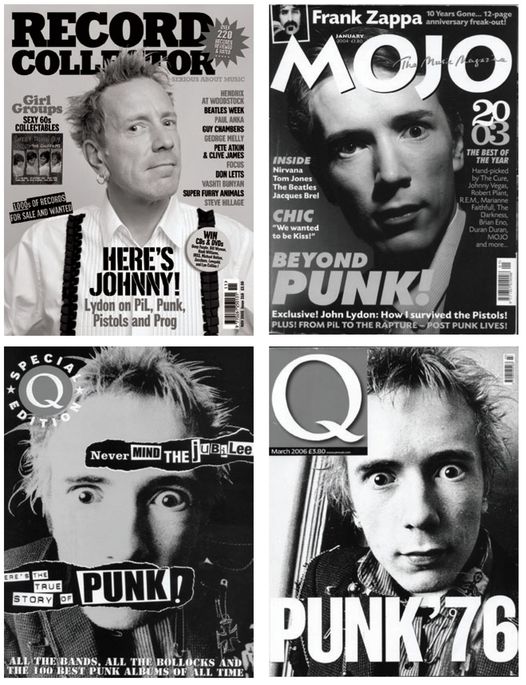

Johnny Rotten’s emergence as a 21st century Renaissance Man seems to have surprised the British public – perhaps unsurprisingly, considering years of cartoon-ish portrayals in the tabloid press.

The fact Lydon is now an international, multi-media celebrity – famous not only for being the Pistols’ most successful survivor, but also the star of reality TV show I’m A Celebrity… Get Me Out Of Here! and an accomplished TV presenter – places him in the curious position of outcast turned folk hero. He’s probably the closest Britain has had in living memory to a Dick Turpin or Jonathan Wilde figure.

For years, Lydon felt misrepresented and unappreciated in the UK. His antipathy towards the British press ran deep, and explains in part his exodus to the States in the early 80s.

As recently as November 2001, when he was asked to accept an ‘Inspiration’ gong at Q magazine’s prestigious annual Awards ceremony, he was privately expressing his concerns to the organisers that ‘the press in Britain don’t like me’. His perception was no doubt coloured by the unfavourable reviews of the Pistols’ performance at Crystal Palace athletics stadium in June 2001; but it was also clear he felt (rightly or wrongly) there was a deep-seated and widespread hostility towards him.

But his relationship with his home country was soon going to change dramatically – and it all began at that Q Awards. After his memorable performance there, the public seemed to twig that Lydon’s original views and fuck-you attitude were just what an increasingly corporate music business could do with. The nation didn’t want the old cove as much as need him.

And what a day it was. Dressed in a cream-coloured suit and with an eccentrically shaved orange hairdo, John turned up at the swanky Park Lane Hotel in a rag-and-bone cart, accompanied by wife Nora and father John Christopher (‘He’s Steptoe,’ he said by way of explanation, ‘and I’m son.’) The top-hatted doormen were somewhat taken aback.

Once inside, Rotten was in an impish mood. His party sat at a large round table towards the back of the hall and enthusiastically tucked into the free wine and beer. He was also accompanied by a handful of old Finsbury Park mates, including John ‘Rambo’ Stevens (also partner in his production company JSJL).

Lydon rattled the opulent chandeliers with an acceptance speech which went like this: ‘Shut up! I’ve got a few words for you. Hello! This is the working class of England – I am one of them! And all you posh bastards out there too busy doing your fucking imitations know where it comes from. I want to say thank you to my family and friends. Stand up and let them know what a real Arsenal looks like! (To a heckler) Eh? You’re a wanker!’

He went on to call comedian Keith Allen ‘a turd’ and praise Kate Bush – ‘I fucking love your music’.

The funniest harangues, however, were bellowed from his table. As Elvis Costello opened the show with a solo spot, he shouted, ‘Oh wonderful! Bloody wonderful! You were boring then and you’re fucking boring now!’ To the sartorially uninspired Starsailor he deadpanned, ‘Nice of you to have made the fucking effort and dressed up for the occasion.’

A photographer was told, ‘Fuck off you wanker! You’ve sprayed beer over my fucking shoes you clumsy cunt! What the fuck do you think you’re doing? Fuck off!’

I, too, was the object of a verbal Lydon flailing. Once the awards had been distributed, I approached Rotten to ask him about his lifelong heroes for a forthcoming issue of MOJO magazine. He told me he didn’t believe in heroes. What about his favourite reggae artists, for example? No, he didn’t want to mention any names, he didn’t want to influence people – it was up to them to work it out for themselves.

Somewhat unwisely, I rose to the bait. ‘Don’t you think that’s a bit conceited? Wouldn’t they work it out for themselves anyway?’ (Which, in retrospect, clearly wasn’t what Lydon had meant).

‘Look, you’re the arsehole with the microphone,’ he growled, ‘sticking it in my face… Fuck off, little boy, or Johnny will give you a slap!’

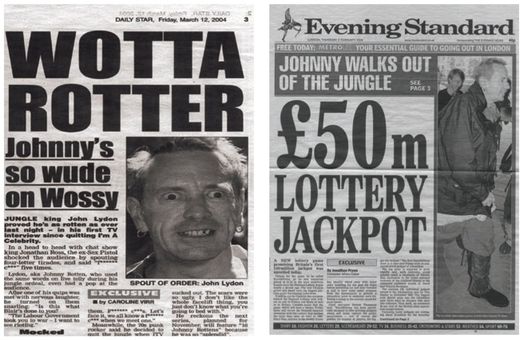

The publicity that Lydon received in the papers the following day confirmed he was the star of the show. His arrival in the cart had delighted the press and his irreverent comments had shown he’d lost none of his old wit and fire. Lydon was suddenly now ‘The Loveable Rogue’ and a dignified, family-friendly punk survivor rather than ‘Terrible Beast of Yore’ – and like only a handful of other working class rascals turned national treasures – Keith Richards, George Best, Spike Milligan – he’d pulled off this feat without ever conforming to the expectations or rules of polite society.

The Q Awards was, then, the start of the nation’s love affair with the then 40-something Johnny Rotten. But what it took to channel the prevailing affection for the man into an expression of widespread public admiration was his involvement in I’m A Celebrity… Get Me Out Of Here! – though he himself seems a little irritated that people regard the show as the key to his newly elevated public profile.

‘I’d been around a long time before then,’ he hisses when I interview him in December 2005. ‘I damn well know that they did a publicity hype around that show… the way Granada (TV) manipulated the press was all about rubbishing your previous existence. This is what sells that show – you never really had a life beforehand. So be wary of that. Hello, I didn’t just become invented by Granada TV! Of all people, Mr Rotten cannot be invented. Malcolm (McLaren) tried that cheeky shit and Granada are part two. It’s nonsense.’

Yet there is no doubt that I’m A Celebrity did help shift a whole nation’s perception of him. Many ordinary folk who knew him only by his Johnny Rotten in extremis persona saw for the first time the vulnerable, warm, witty and sensitive side of this staunchly working class curmudgeon.

On camera almost 24 hours a day for over a week, trapped with a group of other celebrities on a campsite in the heart of the Australian jungle, Lydon’s humanity and bulldog spirit wooed a primetime television audience often topping twelve million. His fellow inmates included model Jordan and ex-Aussie pop star Peter Andre (who subsequently married each other), George Best’s former wife Alex and the disgraced peer Lord Brocket.

A spokesperson for ITV summed up public reaction when she said: ‘(Lydon) has been fantastic entertainment on the show and viewers and his fellow celebrities have found him to be an endearing, eccentric and sensitive character.’

Rotten was seen as friendly, hardworking, community-spirited (collecting wood for the campfire, killing rats, etc) and funny. His comedic, cracked-up face with its tooth-missing grin often filled the screen. In a ‘Bush Tucker Trial’ to earn food for his fellow campers he was viciously pecked by ostriches. He was also deliciously wicked about the contestants he thought weren’t pulling their weight – namely, Jordan – and sent the ITV switchboard flashing when he said ‘cunt’ twice on air.

Jennie Bond, TV’s delightfully posh Royal correspondent, seemed absolutely fascinated and charmed by the man who sang ‘God save the Queen, she ain’t no human being’. She looked at him with the same sense of wariness and awe that a domestic cat would look at a scorpion.

In a fascinating twist, it was revealed late in 2005 that Lydon was considering making a documentary about the Royal Family. It appears his attitude towards them is more complex that you might assume.

‘Yeah, if it’s there, it’s there,’ he explains. ‘I do think they should be looked at properly. Janet Street-Porter did a thing on them and she’s anti-Royal and I never knew that, and I’ve known her a long, long time. And they’re ringing us and asking us to give them the rights to use ‘God Save The Queen’, and we’re saying, “Hang on, right – who’s the bloke who started all this discussion in the first place?” Don’t you think I should have a say-so in it?’

Lydon adds that he isn’t anti the Royals as human beings. He just doesn’t understand how the monarchy can properly function as an institution – and doubts they do either.

Asked if there was anyone he particularly admired from that bunch of people; ‘Charlie for hooking up with Camilla,’ he smiles. ‘I mean, at last he’s married a car blanket! Super. But he clearly loves her. So at last in his daft existence he’s found something he values. And that to me is of value, right? Now that’s a good sign to me. That’s how I look at it. He’s put love above duty when he put duty before. How punishing it was marrying a gorgeous fairy tale bird!’

Princess Diana? ‘Yeah… and was she a nice person? She couldn’t possibly have been. She was a muck-raking, fucking jealous little bitch. Who married into a family knowing damn well that faith and love and truth, these are things that don’t exist in that society.’

He goes on to praise Prince Harry for wanting to fight in the army and being ‘of the people’ and argues that the Royal Family represented a Britishness ‘when there isn’t much Britishness left. Where’s the unity otherwise? I don’t want a fake institution – I want them to be like us and us to be like them, but in a proper way.’

On I’m A Celebrity, viewers are invited to vote for their favourite contestant each day, and the one with the least votes is evicted from the jungle. Ten days in and with seven of the original dozen contestants left, Lydon sensationally packed his bags and walked out.

He didn’t give a reason at the time, but later explained that the producers had failed to inform him that Nora had arrived safely in Australia from the States – despite an apparent agreement to do so. In December 1988, John and Nora were booked to fly on the Pan Am plane that crashed at Lockerbie when a terrorist bomb exploded in its hold: at the last minute they’d cancelled their reservation. Since then, they’ve made a ritual of telling each other of their safe arrival.

But there was a feeling among viewers that perhaps John would’ve left the set anyway: the fact it was a game show designed to mess with participants’ heads didn’t exactly make it a particularly Rotten-friendly environment. Since his dealings with Malcolm McLaren in the Pistols, Lydon has been trenchant about his unwillingness to be controlled or manipulated in any aspect of his life or in any situation: consciously or not, quitting early was the smartest move to make.

His exit completely wrong-footed the programme-makers and threw the game into disarray – very punk rock, very Rotten. It also transformed him into the hero of the piece. In the public’s eyes he was the odds-on favourite to win who forsook his chance of glory on a matter of principle, leaving the crown to go to… homely C-lister Kerry McFadden.

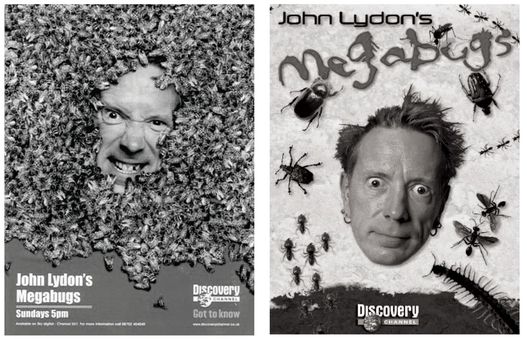

The enthusiasm and empathy he’d shown for the jungle lizards and spiders had an unexpected effect: it immediately led to offers to front TV wildlife shows, including the Megabugs series (John going on the trail of various flies, ants, scorpions and wasps), plus John Lydon Goes Ape and John Lydon’s Shark Attack. The latter, both shot in Africa, saw John, accompanied by Rambo, hanging out with gorillas in the jungle of Rwanda, and swimming with Great Whites off the coast north of Cape Town. The two Gooners’ admiration for the African wildlife was matched only by their determination to buy a replica Arsenal shirt from a ramshackle wooden store in the middle of nowhere. It made great TV – Rotten in a swimsuit an’ all.

Rumours later circulated that the singer donated his substantial I’m A Celebrity fee, reportedly around £100,000, to a chimp sanctuary in Sierra Leone.

Lydon is keen to impress that he takes the TV work extremely seriously. Previously, his series for VH-1 in the States, Rotten TV, had been taken off the air, reportedly because of its provocative content, though he also alleges there was a ploy by MTV (who own VH-1) to grab the ‘Rotten’ brand and ‘use it for other people, like I don’t count’.

He emphasises that he will not be scripted. ‘What I do is free-form, ’ he explains, ‘but it means your brain has to be so fucking in tune you really must be genuine in what you do. The Megabugs thingy, I mean, that’s six weeks solid. There’s not two minutes to spare – gruelling. I love it because I’m fully loaded inside.’

Lydon has also made a series of five programmes about British culture for Belgian TV with the Flemish historian Marc Reynebeau. It tackled the role of the Royal Family and other issues, including the infamous Mosque in his native Finsbury Park, which he found locked when he went to film it. God, he tells me, shouldn’t come with a padlock attached.

So, here I am with Lydon in the week before Christmas in a posh suite at London’s Savoy (‘Hello, I’m at the Saveloy!’ he beams). He will turn 50 next month, on 31 January 2006. Also present is Rambo, sitting in a chair next to him. There seems at first to be an element of Rambo chaperoning his old friend (for reasons that will become apparent later), but he soon melts into his seat, half-listening and occasionally chipping into the conversation to underline a point Lydon is making.

With Nora out in the West End shopping for gifts, we start by discussing Rotten’s attitude towards his current status as household hero and national treasure.

The public perception of you seems to have been turned on its head – ‘John Lydon: The Great Englishman’.

JL: But I see it as, ‘By god, they’ve finally got it right’ – that’s all. Bingo. If I was wrong, nobody would be saying a word here. But I’ve been right. I’m more British now and I don’t even live here! Maybe that’s what being British is… I just like people – the good ones. I don’t like institutions that create monsters.

But you were once Public Enemy Number 1, now you’re something of a national treasure.

JL: And who was helping us? Nobody. (The Sex Pistols) were branded foul-mouthed yobs because a national alcoholic like Bill Grundy taunts us – shame on him not us. That’s the society I come up from. Don’t expect me to be loving that lot anytime soon.

That manipulation by the media must be very galling…

JL: Very infuriating, it really is. And it’s a consistent burden to have to argue it – the more intellectual the publication, the more the compromise and bullshit and devious behaviour. I don’t get any joy in talking to the media, I can tell you that for nothing. You know that.

For somebody who’s meant to have a lazy nature, you seem to be doing a hell of a lot.

JL: I’d love to be (lazy). That would be my vision. I’ve tried hard to be lazy; I’ve really worked at it. I have to take huge breaks because my brain cannot handle it. At a certain point, I will start having seizures if I overwork myself (a legacy of his childhood meningitis). Big time. And that makes me very hard to work with, doesn’t it John?

Rambo: Yes.

JL: There you go. I can’t help that. But I’m far from lazy.

Was that always the way, from the beginning, that work ethic?

JL: None of this is a doddle or a breeze. I’ve made my life very hard in that way. But I wouldn’t get any sense of purpose out of it any other way. I know what my ambitions are – I don’t think I can clearly define them because things that I value don’t seem to be what most people understand or appreciate. I don’t want to be famous – I don’t have a need for it. I bloody like it – it’s great – it’s fantastic, but it’s not the ambition. That’s like being given a suitcase to carry your luggage in, but it’s the luggage that matters. It’s the content that matters.

So with all this TV work, and the Pistols still a going concern – are you now, well, happy?

JL: I like living. Every minute that I live is fine by me and it’s not going to stop, even with the bad stuff. Like when I did time in Mountjoy prison (John was sentenced in 1980 to three months at the notoriously grim Dublin prison following a pub fracas; he was acquitted on appeal). I look back on it and think I did enjoy it there, this is new – what do I make of this? And I did exactly the same on I’m A Celebrity. I thought ‘just be yourself’, come what may.

And they liked you…

JL: Not always – who knows? But if they don’t, then they’re making a problem for me and I’ll deal with that as it comes into my face. I’m not going to shy off from it. It’s like Ireland – my family come from there so it’s not a strange land to me. And every year we had to spend six weeks on a farm with no electricity. So Mountjoy was luxury! The annoyance of that was that my first night in was Friday, film night, and what did they play? They played a fucking punk rock film (Don Letts’ Punk Rock movie). So there’s (original punk scenester) Jordan wearing swastikas with her tits out and me goofing about and there’s these blokes going, ‘Is that you?’ So I didn’t die from knifing, I died from embarrassment! You think, ‘Yeah, we are being a bit daft here’. So you take a double step and correct yourself. You’ve been told something, you’ve been warned. If you’re not learning, you’re cutting out other people.

It’s the institutionalisation of prison. That’s why I hate zoos. And here I am telling you: don’t lock things up – just don’t. Don’t put bars around things. That doesn’t solve criminality. Animals are violent in zoos, they’ve gone nuts. They’re not designed for that. It’s because of confines, lack of opportunities. Being put down, dismissed, left out of things. Poverty breeds crime – though the very worst criminals are the very wealthy.

When you go back to Finsbury Park, has the atmosphere changed?

JL: Sure - I’ll say. It’s very yuppied. The yuppies, they move into these working class areas and they don’t do bugger all for the locals. They want them out. But they want to act like they’re tough and they want to act like they’re part of it. But they’re buying their little weekend dreams. Weekend punks, and it’s all shadowed versions of things. When they come into working class areas, they don’t spread the money about. And there it goes, wicked.

Is there a working class anymore?

JL: No, because there aren’t enough jobs. That’s just basic common sense. I’m not talking ‘knees up Mother Brown, ’round the old Joanna’ working class, that’s cornball. That isn’t what I mean.

In your book, your father says you lost a lot of your early memories because of your childhood meningitis.

JL: Yeah. Bits and pieces have come back over the years but it’s very odd – I can wake up one morning and remember something. So even to this day, I’ve still got bits of the jigsaw missing. And so I have that feeling of not belonging anywhere consistently.

Did your mum’s passing in ’79 change your perspective on a lot of stuff?

JL: I was numb, numb. She asked me to write a song for her when it looked like she was dying, for Christ’s sake, (PiL’s) Death Disco. That song’s me screaming in pain and I don’t even like to think about it. It’s a very strange feeling to do it live, too, because I enjoy being that sad. Strange, strange thing because it’s a release but my god you go through such agony in your head just re-living it. It’s the same with everything I write. I mean every bloody word. I spend a long time thinking about what I do – it isn’t just lazy-arsed shite. Although it’s treated that flippantly by many journalists but that’s their problem, not mine. I find people that don’t do anything for a living hate me the most.

Your parents were quite supportive in their own way.

JL: Well they had to be, they had a loony for a son. I had no idea who they were. That’s a terrible thing, innit? You bring a kid into the world and they go, ‘Who are you?’ (Laughs) What a burden that was. They were just basic Irish folks living in England. And that was bad. There was no doctors nor National Health to help so I ain’t no romantic looking back at then, there was fuck all for you. Fuck all.

But bollocks to it – I love people. I’m a people person. I’m only really happy when it’s out there in the field. Animals and insects, those are the things I understand. See how it operates with them. (Ironically) Thank God he’s given us the burden of the seven deadly sins – greed, jealousy, etc! This is what comes with the gift of a brain and a higher intelligence. Well fuck that. (Points to his head) I want my bathroom sponge back. And on the other hand, I think it’s marvellous what we are as a species. I think it’s amazing. When you go out in the jungles and see that in the eyes of a chimpanzee when it looks at you, and you think it’s going, ‘Cor Johnny, I wish I was more like you.’

Lydon sits back on the settee and lights another Marlboro. This is the last in a whole afternoon of interviews and he’s obviously starting to get tired. Earlier he’d complained to Rambo that his eyes were getting painful and were beginning to smart. Together with his bent spine, their sensitivity is another scar from his spinal meningitis, which laid him up in hospital for a year when he was seven.

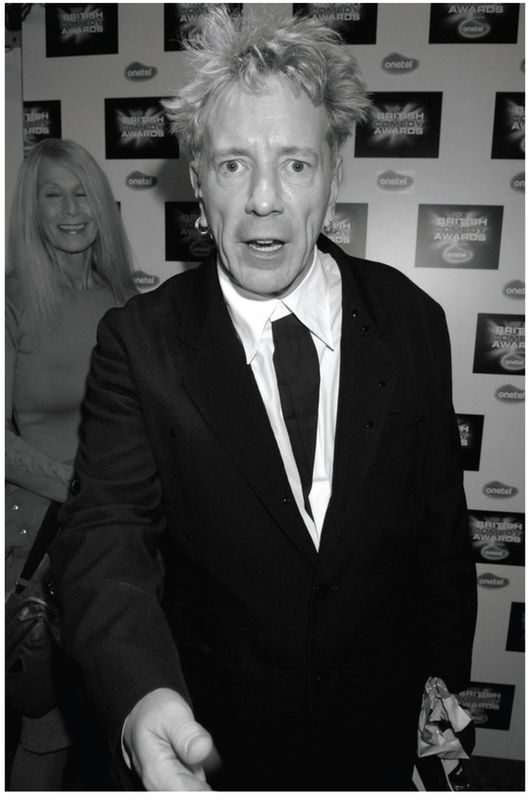

In person, Lydon is unexpectedly friendly between his verbal tirades. Though he and Rambo resemble a couple of squatters in this palatial suite – magazines, books, discarded clothes and empty fag packets litter the ornate, striped upholstery – they also appear comfortable and relaxed. As with his bandmate Steve Jones, Lydon looks remarkably different from his younger self: in middle-age he has grown solid and stocky, and his lined face and missing tooth add to the impression of a rogue-ish, streetwise geezer. If you didn’t know him as Johnny Rotten, you’d probably think he was a north London market-trader or virtuoso hairdresser.

When making a serious point, he looks anxious and thoughtful, punctuating his sentences with plenty of ‘you know’s and ‘alright’s, which don’t invite dissension. When he’s being impish, he’ll refer to himself in the third person as ‘Johnny’ or ‘Mr Rotten’, hunch his shoulders and crumple his face into that leering, Old Man Steptoe grimace.

Lydon tells me he’s taking painkillers, having dislocated his shoulder. ‘How did I do it? (Laughs) Just being an arsehole in a comfortable bed. I do it a lot, put my shoulder out, and it just fucking sprung out at 4am and the pain was so, so fucking bad I thought, “Shit, I’ll ruin this date,” because I had this work to do and I’ve flown all this way and I feel obligated.’

There’s nothing of the martyr about John – he seems genuinely pleased that he’s pushed himself physically and mentally to honour all the interview commitments – but it does make you think about the many ignominies, if you can call them that, that he’s suffered down the years, usually with admirable stoicism. Perhaps the most significant was the knife attack outside Wessex Studios in June 1977, at the height of the furore surrounding the Pistols’ ‘God Save The Queen’ single. Rotten had taken refuge in a car, which was surrounded and smashed to pieces; one of his attackers managed to lean through a broken window and stab him through the hand with a stiletto blade.

After the incident, John became something of a recluse in his Chelsea house, wary of venturing out alone. At just 21, the media had transformed him into a semi-legitimate target for mindless violence.

Sadly, it seems, drinking in London still carries the threat of hassle 30-odd years later. I ask what the reaction would be if we popped to the pub across the road. ‘It wouldn’t work,’ says Rambo.

‘How would I know until I go?’ adds Lydon. ‘But I can tell you outright that any pub round here… safe as houses, I would think. That’s until the arsehole accountant’s had a few more and then the mouthy stuff starts. People generally just can’t seem to butt out of your business. They see you in a newspaper or on TV and instantly seem to think they have a valued opinion about you. That’s OK but keep it to yourself. Time out, mate. No one has the right to butt into your space. Some want to find the flaw and be the one that gets you that way. Others are just wickedly spiteful. And others think, “Oh, isn’t that what punks do, annoy each other?” To me, it means they’re out of kilter with themselves.’

Later, I learn that John and Rambo had had to endure some wearisome remarks by a ‘mouthy accountant’ the previous night in the Savoy bar.

Worse still, Lydon explains, the media aren’t much better. He doesn’t expand on the theme – he doesn’t have to. The group of journalists before me, dispatched by a middle-brow daily newspaper, steamed into the room and tried to goad Lydon into a slanging match. One of them called him a ‘fucking cunt’. The party was bundled out of the room by John and Rambo; incredibly, the journo and photographer then went down to the Savoy’s foyer and began ordering food and drinks on Lydon’s room number. Naturally, the singer was extremely angry and upset.

Experience has taught Rotten to trust none but his own, which explains his tight circle of friends and family and the defensive aggression he uses to protect himself. I notice, for example, that whenever our conversation becomes too cosy, Lydon will suddenly switch into testy Johnny Rotten mode, reinforcing our relationship as journalist/fan and interviewee.

Tucking into the miniature whiskey bottles, our conversation continues.

You’ve talked about the Royal Family, do think a republic would work in a country like this?

JL: I’ll fight for someone who’ll fight for me. There it is. I ain’t fighting for no cunt to have more expensive china.

What about living in the States? How does America view Britain now?

JL: As a piss-pot little country. As a place of insignificance; as a place run by a gormless idiot. Blair is seen as a gormless twat, right, and he’s back-door Charlie to them. Rear entry, mate! The nonsense that he’s whispering some common sense in Bush’s ear – you read stuff like this. Oh yeah, is that how you ended up in Iraq then? Who’s whose poodle?

A million people went out to protest on the streets of London against the War.

JL: If he’d have put his foot down and said, ‘No, we need a good enough reason…’ Before you kill anybody you’d better have a bloody good reason. And that vaguery, that nonsense (about WMD), wasn’t a good enough reason. And so they go to war as war criminals. And these are dangerous words I speak – I go back (to America) on Monday. But I go willingly because I go with a sense of right in my mind. I’m not ashamed to say what’s right. People have died because of these two cunts.

What was your father’s perspective on all this stuff? Did he do National Service?

JL: I’m not going to say what my dad’s perspective is. I’m never ever going to speak for him. Let’s say he travelled a lot around conscription times (laughs).

What do you think was good about Britain in your parents’ generation?

JL: People understood. People stuck by each other. They did. There was communities. When they started replacing pubs with wine bars, community went out the window. It’s gone, it has. Football – teams, fans, it was community based. Now it’s how much dosh you’ve got. Like the Highbury Library full of accountants, ‘Oh come on you Gooners,’ it’s ridiculous. And I’m a season ticket holder – always will be, but I don’t like what I have to put up with sitting around me. Years ago, you’d know everybody around you. You’d be somehow connected. And if you stepped out of line you’d get a smack on the back of the head and your dad would be told. But when the other lot came down your manor… hmm, they’d have to meet your manor on your manor. And that’s important stuff. Those are not rules – those are common sense values that keep things proper.

Were 60s English TV comedies like Hancock and Steptoe & Son big influences on you?

JL: Influences? It’s all there was on TV! You know, it was that or Panorama. Oh god, another Belfast documentary. I point these things out and I don’t mean to be… (tails off) that’s all that went on in my life. I’m an avid book reader but that doesn’t mean I’m a book. Steptoe & Son is the script. That was dialogue I could understand instinctively at an early age about things that were going on around me.

Was that humour reflected in the Sex Pistols?

JL: Oh, like totally. (Ironically) Yeah, like it’s some dour, deep, dark thing with spiteful intent! Well it isn’t. But the spiteful arseholes out there might think it’s that way because that’s how they are. Get it right. Don’t try to reshape my history to accommodate your vision.

Changing the subject, in your book you say your family don’t celebrate birthdays. You turn 50 in a few weeks’ time…

JL: No, we’ve been quite loose about things like that. Which in a weird way has helped me have some sort of independence. You know, because we’re not obligated by those things and don’t see them as duties. And therefore when you celebrate you celebrate because you like each other and not because of an institution. That’s why I don’t believe in morals, I believe in values. There’s a huge difference and I used to get the words confused and then I sorted that out. Anything that has a religious connotation goes. Except now, a contradiction of course is that they tried to take Christmas out of Christmas – I’m not going to gather round ‘the Holiday Tree’, that’s dopey. Kids like Christmas, they like Santa Claus. Is Santa going to become the Gift Person – some politically correct, useless term?

Are you talking about America?

JL: In the States, but it’s creeping over here. America’s kind of running at the same pace as Britain now. It’s beginning to get run down economically. They should call him the Great Leveller Bush.

How many of the Americans you meet in LA dislike Bush?

JL: A lot more than you would be led to believe by the media. People are people everywhere round the world, and I know that because I travelled it more than once or twice. There’s good and there’s bad but Bush is definitely not liked. You get this thing of block-voting Republicans – they don’t actually vote, their vote is connected to being party members. They don’t like him, even them, even the staunchest. It’s seen as un-American to criticise him. It’s almost like Russia years ago where they would have shot you for doing such a thing. You’re just ostracised.

If you were around in the First World War, would you have been a conscientious objector? Would you have been conscripted?

JL: Yes, because I would be fully aware of the brutality of military prison. I’d rather take my chances in a trench, frankly. Why put yourself in a confined space to be brutalised daily? The bullets just might miss you, but the fucking truncheons won’t. There’s always common sense in these things. I do think it should be on a personal one-to-one basis whether you agree to go to a war or not. Hitler would definitely be a ‘Yes, I’ll be there’, but this Iraq thing, ‘No.’ It’s going to have to be run as a police state for god knows how many decades. You can’t invade a country and solve its problems. You’ll be seen as an occupying force. And it’s mad out there anyway and they’ve run their lives that way too long to change it suddenly. You took the walls down in Russia – don’t tell me that problem’s solved. Afghanistan (laughs)! And you think Iraq’s going to get any better? It’s mental.

The interview is beginning to wind up. The photographer is setting up her equipment, and she and Rotten make small talk about her native Ireland. Having chatted all day, John doesn’t seem in any hurry to stop. I tell him I need to use the bathroom, at which point he announces, to much laughter, ‘I need a poo!’

Is it OK if I go first, I ask? ‘Ha, ha!’ cackles Lydon with head tilted sideways and an evil, comical smirk. ‘Johnny Rotten has his own toilet…’

Lydon’s brief absence gives me a moment to think about how, in 2006, he still exists in the public mind as a symbol of absolute rebellion – less the classic outsider who can’t adjust to society (as you might imagine Sid Vicious would’ve been, had he lived; or Pete Doherty, if he survives), but someone who has unashamedly and intelligently played the system to his advantage. Yet unlike, say, the Enron executives of this world, whatever Lydon does seems to be guided by a strong sense of moral purpose: he has a clear view of what’s right from wrong.

Rotten remains, ultimately, the punk archetype. His individuality and unwillingness to conform define the notion of ‘punk’ better than anything or anyone else – next to him, the likes of Iggy Pop or The Ramones appear to have ended up oddly bourgeois. Lydon is also, perhaps, the last great English working class hero to come out of the grim, Up The Junction postwar years of poverty, bombsites, racism, poor diet and unravelling political Consensus. His mantra of ‘don’t accept what society tells you’ is a creed worth handing down to subsequent generations.

In recent months, I’ve canvassed opinions about Rotten from his peers, and it’s curious how they’ve reacted to his career arc. It’s also interesting to see how they relate what he’s doing to the notions of punk he himself established in the first place. (Not to imagine for one moment that Lydon gives a toss what they think.)

Steve Diggle of Buzzcocks, who still tour and record, thinks ‘he does those programmes about lions and tigers really well and he’s still really respected. But you’ve got to be careful you don’t get all showbusiness, ’cos that’s the antithesis of what punk was all about. I can’t imagine Bob Dylan or Joe Strummer doing a programme on lions and tigers… what we did meant something and you must be careful to remind people of that. But Lydon’s powerful and articulate and, the truth is, if it wasn’t for him (Buzzcocks) wouldn’t be here in the first place.’

Shane MacGowan, when asked if he and Rotten were the last true punks standing, wheezed ‘I didn’t know he was still standing. I thought he was kneeling down giving me a blowjob. He’s only a little feller… But he’s alright.’ (Shane was, hard though it is to believe, completely pie-eyed at the time.)

The UK Subs’ Charlie Harper argues ‘it’s great he’s still out there doing it. I think his TV stuff is really cool. Why not?’

Lydon’s ablutions sorted, we continue to talk, mostly about music and the future. The Sex Pistols – who in March 2006 would snub the attempt to induct them into the Rock’n’Roll Hall of Fame – haven’t toured now since 2001, and the last full Lydon solo album, Psycho’s Path, was eight years ago, so…

Will the Pistols play again?

JL: No, we’ve done it. But there’s been an offer in Japan – we might do it ’cause the money’s great but secondly it can be filmed and that can be an end piece. We’ve done England. The hardcore were there (at Crystal Palace) and that’s all that counts. And all those that weren’t, like the other punk bands, can go fuck themselves. They missed out yet again. The Phoenix Festival was a stunner. In a weird way, putting out the singles (for Best Of British Pound Notes), we used samples to get an interest, I want them released. That’s how it is. It’s absurd. And distributed correctly, and I don’t mean selling them down Camden Lock. Virgin isn’t interested – the people who work there are fine but it’s the hierarchy, they’ve lost the plot. They assume people know.

When the Pistols did the reunion in 1996 was there any sitting around beforehand saying, ‘You called me a cunt, etc.’

JL: No, we all know it’s all true so there’s no discussion. We like the fact that we dislike each other and in a weird way that makes us like each other all the more. It’s so brazenly in-your-face honest between us. There’s no problem at all with it. You know, I love being on stage with those chaps and I wouldn’t be seen dead with them off. And they’d be the first to tell you the same about me. Alright. We’re like that.

That’s nice.

JL: (Laughs) No it’s not nice.

Glen Matlock’s taken a lot of stick from you over the years. JL: Well, it’s vice versa, too, you know, vice versa.

So you’re all kind of in it together, you all know the score.

JL: It’s still equal shares mate.

Was it better the second time around?

JL: The way we broke up, we all knew it was broken up for all the wrong reasons. And other people’s manipulations. We reformed and it was the first time we actually got paid for what we did. Up to the end of the Sex Pistols we really hadn’t seen much money at all. It had to involve court cases and all kinds of bollocks that went on for too long and in the interim period I went off and did PiL and they all went off and did their stuff and this cottage industry based on punk and the Sex Pistols built up and it didn’t include us. No-one was offering us a fiver for the bootleg T-shirts. And so back we came and we were hated. ‘How dare you come back!’ Well hello, we’ve come back for our money! The money’s not the big thing. I expected to be paid but the money wasn’t great. I paid a few bills. It’s the fact we now decide what we want to do, alright, and we made that very clear.

Would you ever get PiL back together?

JL: Which semblance of it? You know, 20-odd different albums, many different structures that I approached throughout all of that. But now I’ve put some of the Pistols and PiL songs together on that record, I really love the way they sound together – I’ve never done that before. I’m really chuffed with myself and with my brain and how I’ve conceived music. It’s anti-music throughout, really. And that makes it very, very musical.

What about children – have you ever wanted to do the dad thing?

JL: No, me and Nora… there was a mishap there a few yonks back and, yes, it broke both our hearts but there’s always children around wherever I am, my brother’s kids. One of the best jobs I ever had was before the Pistols looking after problem children. But they sacked me because I had green hair. So there was nothing else to do but become a Sex Pistol. The Sex Pistols wasn’t something I was seeking, there was fuck all else left to do.

I still look out for kids with problems and I always will. I just have a natural affinity for the downtrodden, I can’t help it. It’s horrible and sad and it means your heart gets broken a lot. And there’s so many of these pontificating, arrogant pop stars – their wonderful bloody Band Aid charity nonsenses. They do it in such a cold, businesslike way – they’re removed from the problems, you know, they’re not in there with the nitty gritty. The money I make, it goes all over. But anybody who thinks they can take it without asking, then they’ve got to walk.

Will there be a new solo album soon?

JL: I’m dying to get back and do that. I built my studio with (brother) Martin, we work really well and I can’t be expected to know how every button works and Martin’s very technical. I don’t want to know how every machine works; I want to know what every machine does. And so we’ve found each other in that and that’s great.

Finally, what of that tag on your website, ‘John Lydon – army of one’?

JL: That’s a piss-taker, the American logo. That’s how they advertise that we’re greedy – an army of one, and done in a John Wayne kind of way. That sounds like chaos, mate. So bingo.

And with that we pack up our bags and leave Johnny to inspect Nora’s new purchases, and, interviews over, relax before their flight home. As we leave, the Great Englishman warns me: ‘Be truthful with what you write.’ Hopefully, the truth about Mr Johnny Rotten is in here somewhere.

© Pat Gilbert 2006

Pat Gilbert

Pat Gilbert is the author of Passion Is A Fashion: The Real Story Of The Clash (Aurum, 2004) a book regarded by many as the last word on the Punk legends. He was editor at Mojo for three years, and during this stint also edited The Mojo Collection, a book which documents over 600 of the last century’s most important records. He remains a well-respected commentator on punk music and popular culture in general, and continues to contribute to many music publications.