The Wrecking Ball: Public Image Limited 1978 – 83

Rock (music) is an example of a youth cult that became mass culture over time: pest became host. Punk is an example, like Dada, of a pesky youth cult that threatened to replace the host culture... Whether observers are partisan to pest or host, the interest is in that attacking moment when all risks are poised to leap. Such moments lurk in the history of every movement and the clock never stands still. But to leap is to exchange fluidity for power, inspiration for dogma, and insight for wisdom. Pest becoming host, success becomes hollow: ‘There’s no success like failure.’ Alternatively, when the youth cult leaps and fails, there is no second chance. Instead, threat turns to whimper and predatory forces digest it: ‘Failure is no success at all.’ - ‘Dadapunk’, by W.T. Lhamon.

It is a supreme irony that the English punk movement should take its name from a motley collection of US garage-bands from the late sixties who drew their inspiration from the British Invasion bands of 1964/5; because commercial success for any of these garage-bands was never anything but ephemeral. Even Lenny Kaye’s classic compilation LP of these outfits, Nuggets, must perforce remain a fleeting footnote in the history of pop music. The English punk movement, though vastly more important than its American precursor, also had an inbuilt self-destruct button.

The choices were as limited as the public image – spontaneous combustion or inevitable dilution. It is debatable whether any of the important UK artists who emerged in 1976 and 1977 ever improved on their first records. In the case of the Sex Pistols, the band had already arranged its own demise, sacking Glen Matlock in February 1977. Buzzcocks didn’t make it further than their first EP, before splitting in two; while the Damned lost co-founder Rat Scabies, and all impetus, while rush-recording their second album. The Clash, always professing a desire to overthrow the Rolling Stones, seemed content to parody their mentors.

If punk was modern music’s version of Dada-ism – ‘a short-lived movement in art which sought to abandon all form and throw off all tradition’ – then its second wave (starting in 1978 with a spurt of radical debut long-players), was punk’s Surreal sequel. Generally confused with the New Wave, before becoming the no less definite post-punk, this second wave had its own vanguard, comprising the bands of Johnny Rotten né Lydon, Howard Devoto and Siouxsie Sioux, each a punk paradigm.

These leading lights of the second wave were all starting to think things through, and realised that the negative elements of the punk message could easily decline into nihilism, and considered those that feared progression as the new Luddites. In the case of Howard Devoto (with Magazine) and John Lydon (with PiL) they chose to curtail the pop sensibilities of their punk incarnations (Buzzcocks and the Sex Pistols) and start afresh. In the case of Siouxsie of The Banshees, the band managed to mature before recording any (official) album, and so emerged relatively untainted by their primordial origins.

For John Lydon – no longer Rotten – there had never been any question of a new music being created within the confines of The Pistols. By 1978, he had had his own epiphany – believing that The Sex Pistols were there to bring to an end the history of rock ‘n’ roll, blowing its artificial image up in everybody’s face. His famous epitaph – ‘Ha Ha Ha, Ever get the feeling you’ve been cheated. G’night,’ - uttered at the end of their Winterland swansong, completed the act of immolation.

A sanctimonious exhumation of the corpse of Rock would certainly have flattered the fans and provided Lydon with his pension. Yet, throughout his days in a chilly New York in January 1978, to a sunnier Jamaica at the end of February, such a notion does not appear to have seriously crossed his mind. Keeping his cards close to his chest, he simply informed the awaiting press on his return to Blighty:

John Lydon: I’ve decided to become a parody of myself, because it’s amusing. I’m looking forward to having six kids, a home in the country, a wonderful mortgage, ever so middle-class. And a Rolls-Royce – vintage of course. And a villa on the Isle of Wight. P.S. I am now living with Norman Wisdom.

Actually, Lydon galvanised himself into a frenetic enough bout of activity to recruit two old friends and an expatriate Canadian, for an entirely new band, and by the middle of May 1978 he was beginning to sculpt a new sound. As he typified it in a recent Mojo profile, he, Jah Wobble (né John Wardle) and Keith Levene (ex- of The Clash) ‘were wanting to do something but didn’t know what. The anger in us, different kinds of anger, kinda formed something... The little bit Wobble knew he knew well, and (what with) Keith’s jangling over the top, the two formed such a lovely hook for me. It was like a gift from the gods.’

Jah Wobble was one of Lydon’s oldest friends, having first met at Kingsway College of Further Education in 1971. Wardle was not initially impressed, thinking ‘he was a Led Zeppelin fan. I was queuing up behind him and we had a bit of a quarrel about who was going to put their name down first. He just started crawling around after me, and I let him be my mate. He used to buy me drinks, though, cause no-one liked him then. He used to wind everyone up.’

Jim Walker, a 23-year old from British Columbia, apparently came over to Britain after hearing the wave of exciting music crashing over Albion, and spent a few frustrating months playing with his sticks before answering an ad in Melody Maker that read: ‘Looking for a drummer to play on and off beat for rather famous singer’.

John Lydon: I went through weeks and weeks of rehearsing with everybody who bothered to reply to my ad in the music press. It said something like ‘Lonely musician seeks comfort in fellow trendies...’ I didn’t use my own name because then people who didn’t know how to play would have turned up, and that would have set me back another two years. But the people who did turn up were terrible. Denim clad heavy metal fans... Jim was the only person I liked from the auditions. He’s amazing. He sounds like Can’s drummer. All double beats.

Levene was the one band-member with any kind of pedigree in the new music. Having apparently received classical training in both guitar and piano ‘well into his teens’, Levene was a founder member of The Clash, but left when they started writing songs like ‘White Riot’: ‘I said ‘I’m not fucking singing ‘White Riot’, you’re joking!’ That “No Elvis, Beatles or The Rolling Stones” in ‘1977’ was bad enough for me.’ Levene put his departure down to band politics, the other members to his penchant for illegal substances. Whatever the case, Levene was then part of the short-lived Flowers Of Romance, which also featured future members of The Sex Pistols (Sid Vicious) and The Slits (Palm Olive and Viv Albertine), and then became Slits soundman while he pursued Albertine.

By mid-May 1978, when NME’s Neil Spencer – the first man to review the Pistols – became the first to interview Lydon’s as-yet-un-named combo, the band had at least two original songs worked up: ‘Religion’ (aka ‘Sod In Heaven’) and ‘Public Image’. The words to the former had been written while Lydon was still in The Pistols; while the latter took its name and theme from an early Muriel Spark novel, The Public Image. Its ‘composition’ quickly became a modus operandi for the band:

Keith Levene: We were at rehearsal... We just got Jim in the band so we had a group then. We’re playing away and nothing’s happening. It’s going really bad. Somehow we all managed to get onto something. Wobble was going da-da-da-da-da-da, da-da-da-da-da-da-da (the bass line for the song) and Jim was playing along – all I did was play the B chord all the way through. I went, Stop! Right, check this out – Wobble, do that bass line.” So he did, and I played that (very) solo over it. I told John that he’d come in after we did it four times... (But) as soon as I heard that guitar line, I had it. (from Perfect Sound Forever website, www.furious.com/perfect - hereafter PSF)

Spencer also saw them rehearse two songs from the Pistols’ repertoire, ‘EMI’ and ‘Belsen Was A Gas’, plus a song Wobble introduced as ‘a vision I had last night,’ which turned out to be The Who’s ‘My Generation’. Neil Spencer described what he heard as ‘sound(ing) more like something from Electric Ladyland than your archetypal three-chord punk powerthrash.’ Not punk then. Nor were the quartet a reggae band, despite Lydon and Wobble’s love of all things dub:

Jah Wobble: Rock is obsolete. But it’s our music, our basic culture. People thought we were gonna play reggae, but we ain’t gonna be no GT Moore and The Reggae Guitars or nothing. It’s just a natural influence – like I play heavy on the bass.

Another journalist central to punk’s genesis also got to hear this post-punk progenitor in its embryonic stage. Caroline Coon had known Lydon since the early days of The Pistols, and called her article in a July Sounds ‘Public Image’, though the band remained unnamed, various joke monikers having been under none-too-serious discussion, including The Carnivorous Buttockflies, The Future Features, The Windsor Up-Lift and The Royal Family.

Asked to describe his new sound, Lydon told Coon it was, ‘Total pop with deep meanings.’ However, Coon’s opinion of the band’s progress was not quite so flattering as Spencer’s: ‘Ideally (Lydon said) he’d like to start gigging in six weeks time. On the evidence of rehearsals I’ve heard, however, that seems somewhat optimistic. With hard work and luck, the band could be ready in six months. Recording is another matter...’ It certainly was. By the following week, the band were ensconced in the first of several studios recording their debut single, ‘Public Image’. It was here that they really started to create a sound together, and found the band-name in a song they’d had all along.

Already the songs were coming with surprising ease, but attempts to work on a debut album were hindered by a habit PiL soon acquired of getting banned from studios at a rate resembling the Pistols’ bans from concert venues. Among studios where recording came to an abrupt halt were Advision and Wessex Studios, the ban at the latter (where NMTB had largely been recorded) apparently following ‘an altercation with an engineer... After the dialogue got a little heated, the engineer rather mysteriously launched his head at a bottle which, not unnaturally, broke.’

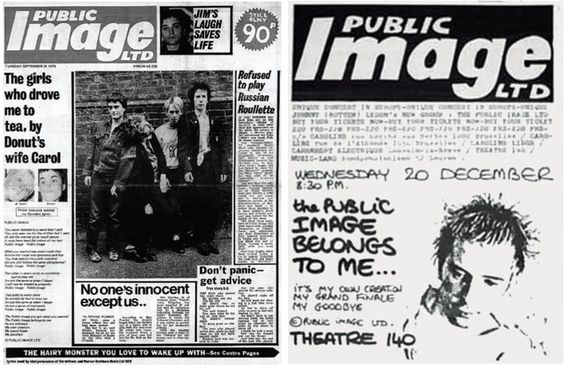

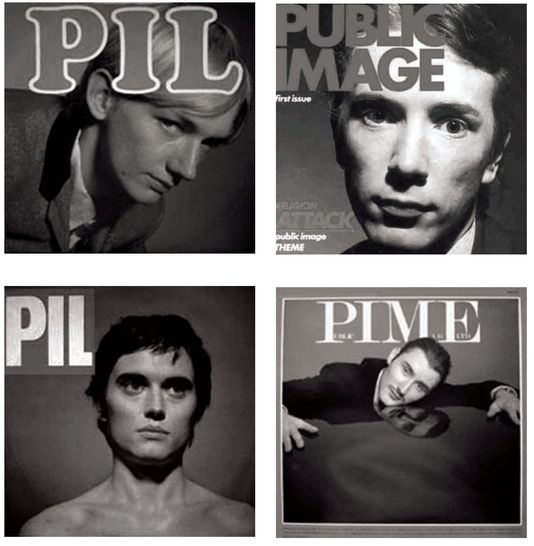

Meanwhile, the new band found they had to address the question of how they marketed themselves. The Sex Pistols had been able to rely on Jamie Reid’s eye-catching ideas for logos, sleeves and adverts, all reflecting a common purpose. Public Image now needed to present themselves as something different, but equally important, and to proclaim their autonomy. The first requirement was a company logo. The now well-known PiL logo, a pill-like design with a black strip down the middle and the letters PiL in black, white and black, was introduced in press adverts for their eponymous debut 45. Hello, hello, hello....

Keith Levene: The PiL manifesto was... no managers, no producers, lawyers when we need them. We’re not a band we’re a company, think up your own ideas, total control. I guess we thought we were a bit important. (PSF)

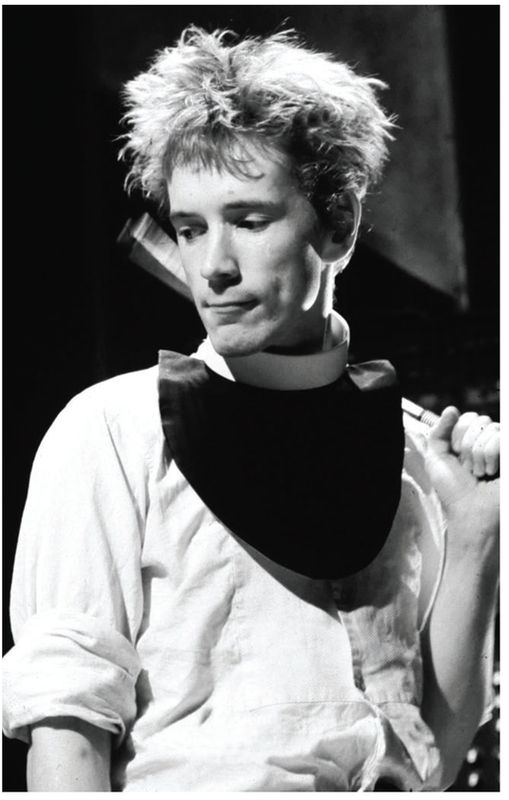

When the ‘Public Image’ single appeared, wrapped in a mock newspaper, it included one of three separate ads, each featuring a different member of the band. In Lydon’s, John asked, ‘How come you’re such a hit with the girls, Keith?’ to which Levene replied in ad no. 2, ‘I discovered PiL.’ Wobble played up to his reputation as something of a hard-case with, ‘I was wild with my chopper until I discovered PiL.’ The parodic ads led some to think the music was also a way of pulling the critics’ legs.

Already their determination to assert their independence was showing a counter-productive side. Due to appear on the punk-friendly TV show Revolver the week their single came out, only Levene turned up at the Midlands studio, accompanied by a mystified Virgin publicist. The other three had apparently absconded to Camber Sands. Producer Mickie Most sat and fumed, retorting, ‘I think he (Lydon)’s done himself a lot of harm, as breaking your contract like that means an instant life ban on independent television. He’s bound to need a television plug sometime in the next 20 years and he won’t be able to get it.’ Though Most was spouting drivel, it was an early indication of PiL’s capacity for pulling itself every which way but forward.

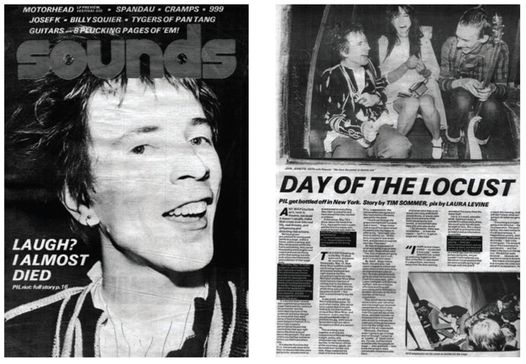

Their live TV debut would have to wait a while longer. Meanwhile, they had filmed a promo video for ‘Public Image’ on a dimly-lit soundstage, for inclusion on London Weekend Television’s Saturday Night People on October 21, drawing the single-word epithet, ‘repulsive’, from self-styled mordant wit Clive James. Though this was their only TV appearance to promote ‘Public Image’, issued on October 13, it still reached number nine in the singles charts, buoyed by a number of gushing reviews, including a mightily enthusiastic one from Giovanni Dadomo at Sounds: ‘It will be a massive hit, and deserves to be’. Indeed, end of the year lists of best singles by Melody Maker, NME and Sounds placed the single first, second and second respectively (losing out in the latter two polls to the Buzzcocks’ ‘Ever Fallen In Love’ and Patti Smith’s ‘Because The Night’).

The song afforded fans their first opportunity to hear Lydon’s new sound. And ‘Public Image’ contained all the quintessential PiL elements: Wobble’s rumbling bass, Lydon’s nasal whine and Levene’s ringing, metallic guitar, while seemingly presenting a pop group fronted by punk’s charismatic commander. But as Lydon sang, ‘The public image belongs to me/ It’s my own creation.’ He was determined to stand well outside any pseudo-Pistols niche others were still looking to place him in.

In fact, PiL were focused more on acruing and collating an LP’s worth of songs, with which to truly stake their claim to post-modernity. An album was what was needed – one to match the likes of The Scream (Siouxsie & The Banshees), Real Life (Magazine), Chairs Missing (Wire) and Live At The Witch Trials (The Fall), all of which had appeared in the last six months, suggesting that punk could yet progress beyond the Ramonesian rant.

Highlighting the fact that the band were working on the album right up to the last minute, the front cover when it appeared listed only five tracks, the other two songs (‘Attack’ and ‘Fodderstompf’) having not been recorded when it had been designed. Lydon commented on some of the difficulties the band faced when their stance was still shiny new in a December 1978 NME interview:

John Lydon: We used nearly every studio there is. We ran out of them in the end. They’re all so-o-o-o bad. They all cater for MOR sounds. If you want anything out of the ordinary out of the desks it gets really difficult. To get the sound that’s on that album is so hard in those places. You have to go through so much bullshit. And all it is, is trying to get a live sound – the way any band should sound on stage... You’ve always got shithead engineers who won’t show you the ins and outs of things and who scream blue murder when you turn anything up full.

Of the songs on the album – christened First Issue – it was the closer, ‘Fodderstompf’, which would come in for the most critical flak. Lydon told Chris Salewicz, ‘You should’ve seen Branson’s face when he heard that... He was furious.’ The song, a seven-and-a-half-minute exercise in ‘disco dub’, seemed like a self-conscious device to stretch the album beyond half an hour. Yet what had come before was already radical enough, as Levene recently told Simon Reynolds:

Keith Levene: The first album is the one time when we were a band. I remember worrying a little at the time: Does this do too much what we publicly say we’re not going to do? – meaning rock out. But what we were doing really was showing everybody that we were intimately acquainted with what we ultimately intended to break down. And we started that dismantling process with the album’s last track.

‘Fodderstompf’ aside, First Issue was neatly divided between a trilogy of concise, riff-driven rants, à la ‘Public Image’, and a trio of lengthier excursions that gave full vent to the rhythm section’s sledgehammer power and Levene’s penchant for improvisation. Particularly disorienting was the album’s opening track ‘Theme’, a largely improvised, nine-minute excursion into what it feels like when, ‘it’s dawn on a wet Wednesday in Chelsea and Britain’s most powerful punk singer... is feeling like death.’ Of all the tracks, it seemed like the one with which Lydon seemed most happy:

John Lydon: We did that about four or five in the morning. We’d already done a couple of takes but the machine was wrong. Really irritating. I think it sounds great. It’s like there’s a barrage of guitars all over the place but it’s just Keith’s one guitar. He’s amazing – the racket he can get out of that thing! He’s got all the madness that The Pistols had at the start.

Despite the pulverizing nature of the PiL piledriver, most reviewers still felt short-changed. Pete Silverton’s review in Sounds was among the more misguided: ‘A producer friend said it sounded like a band (who had) gone into the studio for the first time, and run riot with all the effects.’ Nick Kent did his best to push the band in what he saw as a more productive direction, designating ‘Public Image’, ‘Attack’ and ‘Lowlife’ as ‘musical territory that, given time and effort, will provide them with a strong and individual foundation for future focus and experimentation.’ In fact, that direction was already abandoned, in favour of wilder, more dub-like extempori-sations. Songs like ‘Theme’ sign-posted PiL’s future direction, the collective nature of the sound reflecting PiL’s communal approach:

John Lydon: In this band we are all equal. No Rod Stewarts. We all do equal amounts of work, we all produce equally, write songs and collect the money equally... We’re just the beginning of a huge umbrella, we can each do our own solo ventures to our own amusement so long as they don’t infringe on the band as a whole. I want it to spread out. I know that might sound a bit idealistic.

It was in these early album reviews that one first encounters the idea, expressed throughout PiL’s creative five-year journey, that the band was some elaborate joke on Lydon’s part (by the time he actually turn PiL into a joke at fans’ expense, in the aftermath of ‘This Is Not A Love Song’, few were sure when the sniping began). One reviewer of First Issue concluded that Lydon was trying to lose his audience, that the album was deliberately anti-commercial: “Johnny Rotten is going to lose quite a few fans with this record, but... that seems to have been the purpose of it anyway.”

Keith Levene: They all slagged (First Issue) because it was self-indulgent, non-simplistic and non-rock ‘n’ roll. Those are all good points. But that’s the kind of music we intend to make. (1980)

Despite its share of critical flak, the album appeared at number 28 in NME’s list of the ‘Best Albums Of 1978’ (and at twenty-two in the charts). Kris Needs at Zigzag certainly cast his vote in the band’s favour, writing about how ‘PiL have already got their own sound, and this album has moments as biting as any Pistols song. No resting on laurels. No waste.’

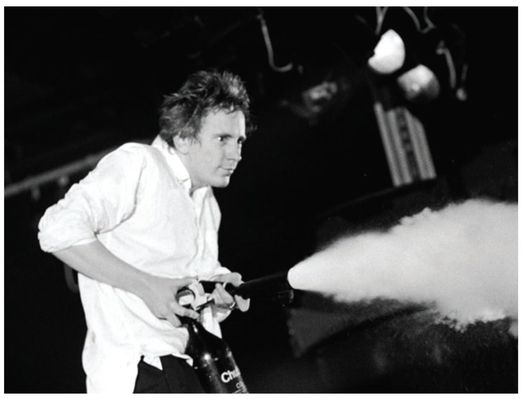

If PiL was always supposed to be more than ‘Lydon and lackeys’, two solo ventures designed to reinforce this notion now slipped out of the Virgin vaults: Jah Wobble’s exercise in dub, ‘Dreadlock Don’t Deal With Wedlock’, and a 12-inch EP called Steel Leg Versus The Electric Dread, featuring Keith Levene (billed as ‘Stratetime Keith’) Jah Wobble, and resident rapper at PiL HQ – Lydon’s house in Gunter Grove, SW6 – Don Letts. Letts contributed lead vocals on the hilarious ‘Haile Unlikely’, while the weird and wacky ‘Stratetime And The Wide Man’ made further use of the same fire extinguisher found on ‘Fodderstompf’.

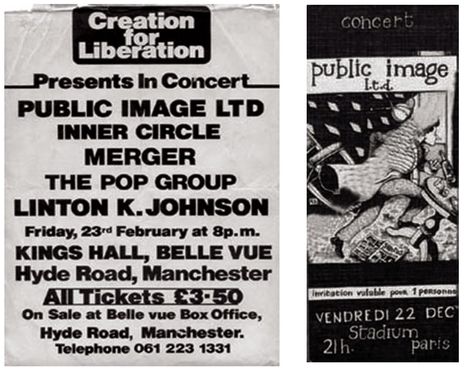

Altogether more significant was the full cooperative’s live London debut at the end of December. Two shows in Brussels and Paris were hastily arranged as warm-ups for dates at The Rainbow on Christmas and Boxing Day. In fact, the first gig in Brussels did not go too well, the band playing just six songs before the ubiquitous Belgian riot curtailed further extemporisation.

Thankfully the Paris show was more successful. The sound was suitably immense and the crowd responded enthusiastically. In fact, when PiL ran out of material they were obliged to play two songs from The Pistols’ own repertoire, the controversial ‘Belsen Was A Gas’ and a one-off version of ‘Problems’. When that still did not suffice, they ran through a couple of First Issue songs again (‘Public Image’ and ‘Annalisa’). The success of this show convinced the boys they were on the right track, even if both Wobble and Lydon were already expressing concern regarding the band’s likely reception in London.

Jah Wobble: Johnny Rotten is gonna lose, Keith Levene is gonna lose, Jim Walker is gonna lose. And all the kids are gonna watch us get our heads kicked in.

John Lydon: I’m going out of my way to even walk out on a stage, knowing that three-quarters of the audience won’t be there just to listen to us, but to slag us off and survey and suss it out.

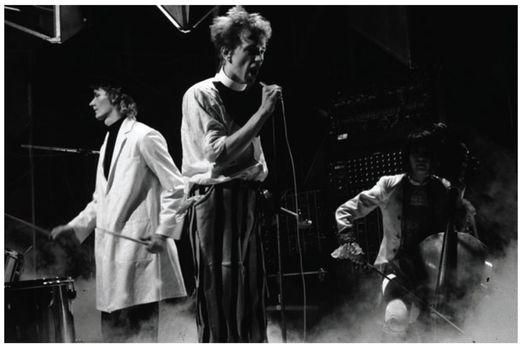

The Rainbow Theatre. Christmas Day. The place is packed to the gills with fans awaiting the emperor’s unveiling. As Wobble, Walker and Levene take to the stage, they launch straight into ‘Theme’, which fills the theatre with a crushing, monstrous, punishing sound. The stage looks fantastic. All green and black. Finally Lydon saunters on, carrying two overfull carrier bags, containing a supply of lager to get him through the forty-five minute set.

But this is a continuation of the confrontational Brunel show (the Pistols’ last ‘London’ gig). Tonight is not about participation, even if Lydon first tries that route by handing the microphone out during ‘Theme’ for occasional, disorientating shouts of ‘I wish I could die’ from assorted members of the audience. After almost a quarter of an hour, the monumental sound finally dies down. At last the audience can make themselves heard: ‘Submission’, ‘Anarchy In The UK’, ‘Pretty Vacant’. Lydon gets straight to the point: ‘We’re not gonna play any fucking Sex Pistols songs. If you wanna hear that, fuck off! That’s history.’ ‘Lowlife’. Then ‘Attack’, which the NF skins, who have been an ominous presence throughout, take as their cue to start a fight. The band stop and Lydon shakes his head, ‘You never learn’.

The crowd steadily becomes – as reviewer Keith Shadwick recalled – ‘more and more confused and restless between numbers as their relationship with the band became more and more remote from the usual performer-audience axis, (while) Lydon would spend five minutes or more between songs in intense arguments with interjectors.’ Some particularly phlegmatic punk at the front gobs right in Lydon’s face. Lydon leans down and gobs right back, but his aim is untrue. He hits the guy in front, then calmly leans over and flicks the frozen phlegm off the guy’s shoulder onto the Mohican-head behind.

Those at the front keep asking for Johnny to give ‘em some lager. He finally obliges, dispensing several cans to the audience, only to get one back, unopened, full force, right in the face. Blood trickles down his forehead, where the can has hit him. Lydon stands over the stage, ‘Come on mate. Just you and me. The bouncers won’t touch you.’ There is no response. By now, as Shadwick would later suggest, ‘The real focus of the event was outside the music. It was in the battle between a man and his own public image, this being a microcosm of the central conflict in rock. Here was one of the great figures of his time desperately trying to state clearly his own control of himself.’

‘Public Image’ is the encore, though PiL never actually leave. Afterwards, Levene, Wobble and Walker sidle off the stage, as the immense sound dies away, leaving Lydon stage-right, crouched down, still calm. As he kneels, many members of the audience are refusing to leave. They want an explanation. Those crowding to the front are now in two camps, on the left PiL proselytizers, on the right those who came to harangue the man. Lydon is suitably snide, sarcastically putting down those content with their ‘pink vinyl singles and Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindles.’ The (admittedly futile) lecture continues. He has already left them behind.

Yet the reviews of that first London show were surprisingly unsympathetic to Lydon’s (and PiL’s) predicament. Sounds – no longer the paper of Savage, Suck and Sandy – devoted a whole page to a review of the show, written by someone who thought ‘the album was disappointing (though) ‘Low Life’ and bits of ‘Religion’ were good’, and who spent most of the second half of his review blaming the band for the fact that he couldn’t get a taxi after the gig. Meanwhile, punk fanzine Ripped And Torn decided not to mince words with Lydon: ‘You fucking pathetic little puppet with your totally indulgent wallowing mess of an album... and your wanky little statements about ‘never being a punk’. I wonder where this one was standing at the end of the concert?

After all this controversy, the Boxing Day show was anti-climactic, passing without any real incident. Since it became the bootleg album, Extra Issue, but no real sense of the drama of opening night permeated beyond its immediate recipients. Public Image would not play London again for another five years and the ersatz PiL that finally played the Palais in November 1983 bore no resemblance to the idealistic band of yore. By then, the clink of the till had indeed triumphed.

PiL’s volatile clash of personalities was already proving too much for drummer Jim Walker who, after four gigs at the sticks, called it quits in the new year, muttering what would become an increasingly familiar mantra, ‘This is a business, it’s not just sitting around a flat, taking drugs and being grey... But (the others seem) more interested in “communications videos” and sitting around and mismanagement.’ Walker was to be the first of a procession of drummers streaming out of Gunter Grove. His departure broke the band’s all-important unity of four. For the next eighteen months it would be a unity of three; then two; and finally one. The official line on his departure was surprisingly traditional – ‘dissatisfaction with musical direction in the group structure.’

His departure made any further spreading of the word problematic. The band had planned ‘a series of one-off appearances’, the first of which, at the Dublin Project Arts Centre on February 16th, had already gone on sale. When the date for commencement of legal proceedings brought by Lydon against his erstwhile manager Malcolm McLaren coincided with the scheduled Dublin gig, he had the perfect get-out and the show was cancelled.

However, PiL still intended to proceed with a show at Manchester’s King’s Hall on February 23rd. In aid of the Race Today Friendly Society, it was christened ‘Creation For Liberation’. Manchester, less fashion-conscious than London and already responsible for the most experimental punk scene in the country, was likely to be a lot more receptive than the capital. Now all PiL needed was a drummer. One seemed to be to hand in the form of Karl Burns, who had recently quit The Fall, the fourth member to do so. There was barely time to assimilate Burns into the set-up.

Lydon had spent much of the previous week wrestling back control of his work-to-date from McLaren, leaving little time for getting acquainted with PiL’s latest recruit. Indeed at the Manchester show ‘Belsen Was A Gas’ would collapse mid-song due to a lack of rehearsal, much to Lydon’s amusement, ‘Fuckin’ egg on face time.’ The court case, which received considerable media attention from both the national and music press, finally concluded on February 14 when the judge appointed a Receiver to safeguard the assets of Glitterbest, pending their division among the four Pistols and/or their heirs.

It wasn’t Lydon’s only contact with the law that month. A police raid on Lydon’s home at 6.30 am on February 13th was the second such raid in a month. Taken to Chelsea Police Station, Lydon was released without charge. Such petty harassment was becoming a regular feature of life in Gunter Grove, where the communal lifestyle and regular retinue of Rastas and known drug dealers knocking on the door gave the police due cause. Lydon’s response was to ask his friend Dave Crowe to come and live at the house as the first line of defence, effectively making him the house bodyguard.

The Manchester show, where PiL were supported by the equally audacious Pop Group and Rasta poet Linton Kwesi Johnson, provided welcome relief from such incursions. Though King’s Hall was something of an acoustical graveyard, Lydon was enthused by the reaction, later commenting that ‘the sound is second to the atmosphere. Up north the shit didn’t mean much. They either like it or hate it. They liked PiL. Only in London do we get Sex Pistols requests, ha, ha.’

Reviews were also more favourable than for the Rainbow shows. Paul Morley got it spot on, writing in NME: ‘PiL play it blank and cryptic, offering no easy clues or anything tangible to grab hold of. They satirise, ridicule, delude and elude. It’s a joke, a challenge, an indulgence, an assertion, a revenge, an adventure, a disturbance, a fascinating rock ‘n’ roll sound. You take it seriously or you don’t. Whichever way, they’re incredibly important.’ Sounds reviewer and local lad, Mick Middles, also ‘left totally convinced that Public Image are more than a major force in today’s music scene.’

However, PiL didn’t feel sure enough to play any new songs to the Mancunians, though they were soon back in the studio working on further material. Recording at Jah Studio, presumably with Burns on drums, the band taped what early reports called a ‘modern version of Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake.’ Lydon’s mother had recently died of cancer, and the harrowing work (better known as ‘Death Disco’) provided an anguished description of Lydon’s feelings losing someone very close to him. The product of Lydon’s cathartic grief and Levene’s rich instrumental imagination, it plugged directly into the moment:

Keith Levene: I would play the E chord and it would be like breaking glass in slow motion ... The whole thing was in E. That opened it up, ‘cos it was all literally in one note. I realized that this tune that I was bastardizing by mistake was ‘Swan Lake.’ So I started playing it on purpose, but I was doing it from memory... When he’d stop (singing), I’d play ‘Swan Lake’. When he’d sing again, I’d go back to the harmonic thing and build it up. (PSF)

The song had first been worked on with Walker, but was the solitary solid statement to come from the Burns-era PiL. By the time of its release, he had been replaced by ex-101’ers drummer Richard Dudanski, summoned to the Townhouse studio to sit in that spring, without explanation or advance warning:

Richard Dudanski: The next ten days, we recorded like five songs. The tape was just left running. Basically, me and Wobble would just start playing, and maybe Keith’d say something like double-time. But it was a bass-drum thing which Keith would stick guitar on, and John would there and then write some words and wack ‘em on... once we’d got the (basic tracks). I think the first day we did ‘No Birds Do Sing’ and ‘Socialist’. Then we did ‘Chant’, ‘Memories’.

Dudanski, who had been brought in after someone apparently thought Burns was a verb, says, ‘I was really thrilled when first joining PiL. I shared the whole (idea) of wanting to do something different and not controlled by the industry.’ He also found Lydon to be a true music lover, listening to everything from ‘a little madrigal, or Renaissance music, a lot of Irish folk music... (to) Bulgarian voices, Indian stuff, a lot of Islamic percussion stuff.’

As a mildly humorous interlude – and one more way to debunk his status as pop icon – Lydon agreed to be a guest on the BBC’s revival of Juke Box Jury during June, hosted by the faintly nauseating Noel Edmunds. Asked at the outset what music he listened to, Lydon replied, ‘My own.’ Acting throughout like a delinquent modern-day Groucho Marx, he eventually grew bored of the whole fiasco and made one of his famous impromptu stage-exits.

With Dudanski now fully ensconced in PiL, the band played its second gig of the year - returning to Manchester. This time, though, it was a secret gig at Russell’s Club, organized at the last minute by Tony Wilson, with PiL playing to barely a couple of hundred punters. On June 18, in one of Manchester’s dodgier districts, Hulme, PiL debuted over half of their forthcoming album. Indeed, in their one-hour set, the band featured only two songs from the first album, ‘Public Image’ (which they did three times, before getting it right) and ‘Annalisa’.

The five new songs were all long, droney and opaque affairs. ‘Chant’, ‘Death Disco’, ‘Memories’, ‘And No Birds Do Sing’ - into which Lydon interjected several couplets of ‘Arsenal 3 ‘Nited 2’ to taunt the few United fans there, his team having beaten Man United 3-2 in a memorable Cup Final weeks earlier – and ‘Albatross’ were like nothing this audience had heard to date, even those who had caught earlier shows at the same club by Joy Division and Magazine.

Eleven days later PiL released ‘Death Disco’ as their second and third singles, giving fans two versions of the song, and two alternate b-sides. Its 7” guise came with ‘And No Birds Do Sing’ on the B-side; while a more langorous six-minute ‘Mega-Mix’ of this modern Swan Lake, on a 12-inch, came with an instrumental version of ‘Fodderstompf (entitled ‘half mix’) on the other side.

Melody Maker’s Chris Bohn called the extended 12” version ‘the most awesome and complete musical experience since Can’s Tago Mago. Most importantly, though, it’s the one dance single of the year to define its own style, without shaping someone else’s to suit its own needs.’ If the single suggested that the group had set their controls towards the organised chaos of ‘Theme’, it still managed to chart, thanks to another bout of favourable reviews and an appearance on Top Of The Pops (where they performed live in the studio).

The band also appeared on a new Tyne-Tees pop programme, Check It Out, at the beginning of July, performing a live version of ‘Chant’. After this powerful preview, though, they were again subjected to a cheap publicity stunt. The presenters introduced a film of Mond Cowie of the not-so-Angelic Upstarts, bad-mouthing ‘Johnny Rotten’ – without PiL’s prior knowledge – and then asked for a response. Needless to say, Lydon told the unprofessional presenters that this was ‘a cheapskate comedy interrogation act, and it just ain’t on,’ and duly walked off – again.

Jeanette Lee - now Levene’s girlfriend, and PiL’s occasional mouthpiece – summed up the feelings of the PiL camp when she told NME, ‘You can understand that the whole cheap affair was an attempt to goad John into doing his nut and giving the show a great deal of publicity. It was sickening.’ The following month Levene and Lydon were interviewed, more civilly, for Radio Merseyside. Levene took the opportunity to comment on the prejudices the band faced at this point:

Keith Levene: At first they expected the band to be an extension of The Pistols and it wasn’t, it didn’t occur to them to pick up on what PiL was. Instead of that they became kinda intimidated by it again – just because we were something different. That’s what we get all the time just because they’re not prepared. It doesn’t occur to them to just pick up on what we are doing. They expect us to start gobbing and spewing up.

The whole band was starting to feel the overweening pressure of false expectations. Lydon in particular was constantly called on to defend his actions. But at this point he still believed he might prevail. In a letter to a fan in August 1979, Lydon spelt out his ‘message’: ‘Anything soundwise that breaks the pattern won’t even be heard by most and PiL are not a typical sound... PiL will win. Rock ‘n’ roll is dead. It all is... Music is collective noises, there must be no limits.’

Continuing to arrange a series of one-off concert appearances, rather than tour this tiny island, PiL were able to secure the greatest exposure for the minimum amount of effort. In August, they consented to headline the first night of the Leeds Sci-Fi Festival, to be held on September 8 at the Queen’s Hall; sharing the same stage as Joy Division for the one and only time. It would be PiL’s final UK show as a unit of innovation and improvisation – and the last featuring Richard Dudanski.

Leeds’ response to PiL was as apathetic as their response to the Pistols, who had played the Polytechnic on the famous Anarchy Tour. If, by 1979, Mancunian fans didn’t shout for Sex Pistols songs, they certainly still did in Leeds. As if this wasn’t bad enough, one fan lobbed a full can of lager not at Lydon this time, but at Wobble. Lydon duly turned his back on the audience during the third song, remaining that way throughout the rest of the set, a gesture misrepresented in most press reports of the show.

The fickle music press again preferred to take potshots at PiL rather than condemn their ‘fans’. Andy Gill – the hack, not the Gang of Four frontman – failed to identify most of the songs in his NME review, though only three of the nine songs remained unreleased (‘Chant’, ‘Memories’ and ‘Another’). The Sounds reviewer, speaking on behalf of the Luddites of Leeds suggested, ‘One measly rendition of ‘Pretty Vacant’ would have converted an expensive extravaganza into a rock n’ roll concert.’ Talk about missing the point! The most negative assessment of the gig, though, came from Keith Levene: ‘We did a shit gig, to a shit audience in a shit place. We had a horrible time.’

Two related results of the Leeds gig were the departure of Richard Dudanski, and a decision by the band to avoid further UK shows, for the time being at least. Dudanski duly wrote to NME editor, Neil Spencer, to announce the reasoning behind his departure:

‘Dear Mr Spencer,

In the absence of any statement from PiL, I would like to inform you that as from our Leeds gig I have ceased to be a member of that group.

My disagreements and inability to work with certain members of the group in particular, resulted in mutual satisfaction at my exit.

My only observation is that what could potentially be a great band, will probably do just enough to retain its guaranteed success. Perhaps exactly because of this guarantee, the really good ideas behind the band will never be more than just that. I hope not for JR’s sake.’

Dudanski’s departure threatened to disrupt the band’s attempts to put the finishing touches to their second album, upsetting the finances of the band, at least one of whom now had a habit to feed. The high-strung Levene simply set about recording the requisite drum tracks himself. By this point he had his own idea of how he wanted to work and, as the one true musician in PiL, expected the acquiescence of others:

Keith Levene: With Metal Box, we became experimental very quickly... The way I saw it, the desk became an instrument. It was such a major part of the process. For the whole thing, the whole studio was becoming a big synthesizer... I told (the engineer) to record everything because we didn’t know what the records are. So we didn’t know when we were playing a tune or not. Sometimes we might have played something and it sounded like we were fucking around and it turns out to be something very serious. (PSF)

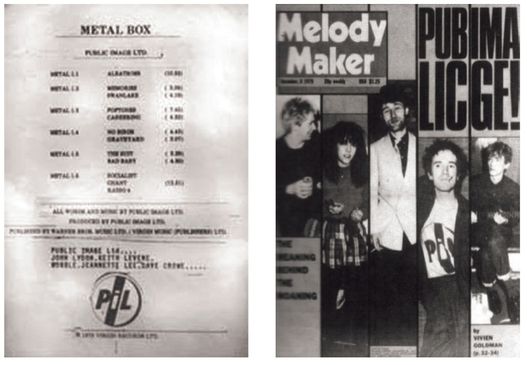

At this stage, he also maintained impetus by recording a pair of songs without any drums – ‘Radio Four’ and ‘The Suit’. By the end of September it was announced that the second PiL album would consist of three 12-inch singles, “with an aggregate playing time equivalent to that of a normal LP” and would come in, “a cross between a film can and a biscuit tin” (much like the original ‘albums’ of records, which were sets of 78 rpm records in an ‘album’). The set, which was to be entitled Metal Box, would be released on October 12, with a preview single, ‘Memories’, issued the week before.

‘Memories’ was certainly a good indication of the direction the band was heading in with their new album, though it was no more commercial than ‘Death Disco’. The Sounds review summed up many people’s disenchantment with Lydon’s lot, ‘Memories’ is an apt enough title as this brings back memories of all their other rubbish. ’ But in NME, Danny Baker made the record ‘Single Of The Week’, while admitting that ‘Memories’ has no place within today’s broadcasting set-up.’ He was proven right when the single reached the none-too-dizzy heights of number sixty in the charts.

Both ‘Memories’ and its B-side, ‘Another’, had been recorded with Dudanski - also being performed at his Sci-Fi swansong – so the single, pressed as both 7” and 12”, was in the shops on time. But it came as no surprise when the album was deferred until November 16 because, as Virgin announced, ‘not all the tracks have been delivered yet.’ The last track delivered also proved to be the audition for PiL’s fifth drummer, Martin Atkins (Dave Humphries having seemingly come and gone in the interim):

Martin Atkins: It seemed that every time I opened a music mag PIL had fired another drummer - I’d call every time but someone else had filled the gap. One night I was sitting in my flat in Willesden... reading through old copies of NME - I found ANOTHER drummer had quit/been fired - actually I think that Karl Burns (yikes) from The Fall was actually set on fire... I called up Jeanette Lee... it was eventually agreed that I’d meet up with them the next weekend at the Town House which I assumed would be a rehearsal room. Errrrrrr. It wasn’t - I walked in - to comments like – – ‘here’s that northern git!’ - and we wrote ‘Bad Baby’ (on the spot).

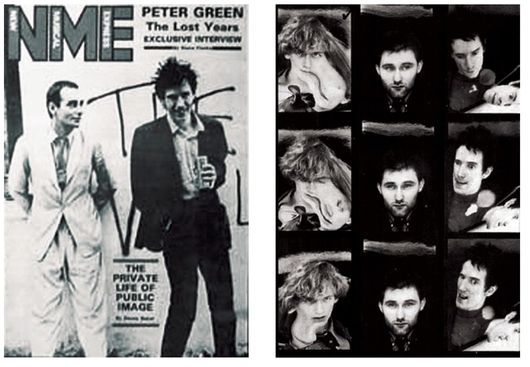

In the month since ‘Memories’ blipped across the lower regions of chartdom, advance copies of Metal Box (minus the tin!) had been sent to the music press, or played to the likes of Kris Needs and Vivien Goldman at the Gunter Grove grotto. In both instances, the experience prompted an ecstatic critical response. Though the band maintained a highly ambivalent relationship with the UK music press – and vice-versa – Metal Box was to be the one instance where critics united in praising PiL’s achievement. Angus MacKinnon in NME summed up the critical consensus when he wrote: ‘All this forward flow in 12 months – it’s almost frightening. PiL are miles out and miles ahead. Follow with care.’

Even Sounds, previously the most antagonistic of the major UK weekly music papers, devoted a page to the album; Dave McCullough not only giving it five stars, but attempting to evaluate its likely future importance: ‘Metal Box is a vital ending to seventies pop culture and a sizeable nod in the direction of a real rock ‘n’ roll future. The last laugh is with John Lydon and no mistake.’

Though the album came without a set of lyrics, press adverts corrected this oversight. Full page ads simply carried the band name at the top, the album title at the bottom, and the lyrics scrawled between, untitled and out of sequence. With the surprisingly effusive critical response Lydon faced a new problem - repeated questions as to what this or that song meant. ‘Poptones’, a story of rape viewed from the female vantage point, prompted more than most. He tried to deflect such enquiries when on BBC Radio One’s Rock On. Asked how they write songs, he replied: ‘We take a silly tune and strip it bare, and start again.’ As for their chosen format, PiL went to great lengths to call it anything but An Album:

Keith Levene: It’s not an album. You don’t have to listen to the songs in any order. You can play what you want, disregard what you don’t. Albums have a very strict format, the eight tracks, difficult to find, I hate all that – the quality is usually appallingly low, almost unlistenable. We can’t get our sound on a normal record, you can’t get the depths and heights.

Though there was no place for lyrics, the ‘album’s’ insert found room for two additional members of the limited company, Dave Crowe and Jeanette Lee. By December, Levene was referring to the group as ‘a unit of five, three public,’ with ‘the band bit of PiL as just me, John and Wobble... we have had various drummers, and they’ve always been told what to do and play. It’s just one of those equal things.’ Already history was being rewritten, at the expense of Walker and Dudanski. Vivien Goldman, a regular visitor and coconspirator, suggested at the time that Jeanette Lee ‘does the bulk of liaising with the outside world, as far as I can make out, though everyone in PiL refuses to say exactly what they do... Jeanette will (also) be making a film record, a kind of diary, of PiL.’ Actually, she was now Keith Levene’s girlfriend first, and everything else second:

Keith Levene: She was supposed to be in the band as the video person, but she hadn’t done shit for ages. I got her in the band based on the idea that it was cool to get band members that didn’t play instruments... I was crazy about her, I didn’t know that she wasn’t doing anything ... Wobble (had) said, ‘What’s she gonna do – be a secretary?’ I said, ‘No, she’s gonna do video. ’ He hated her. (PSF)

Levene also informed a slightly sceptical Goldman, ‘We’re into vision - video - we’ve got this Super-8 camera... we want to use electronics as special effects, using electronics to condense the quality of the Super-8.’ Goldman summed up PiL’s predicament at the end of her December 1979 Melody Maker cover story: ‘PiL still haven’t reached what to me seems the ideal stage: sending a constant stream of communiques, records or otherwise, that would remove them from the pitfalls of the “PiL album – an event – articles in the music press soon come” syndrome.’

For now, communiques remained confined to conventional media. In November PiL recorded three songs for a session on John Peel’s late-night Radio 1 show. This ‘Careering’ gave the band ample opportunity to improvise new sounds, and for Levene to display his increasing preoccupation with synthesizers. The guitar was becoming increasingly sidelined as the synth became his instrument of choice. Part of the problem, as he later explained, was that ‘once I got good enough to know the rules, I didn’t want to be like any other guitarist.’ Lydon, though, suspected a psychological uncertainty in his friend:

John Lydon: Keith really lacked confidence in himself. Such a shame. He was one of the most talented fucking guitar players I’ve ever known. He made a guitar do things that were not supposed to be possible. But he just didn’t see the value in it. (2004)

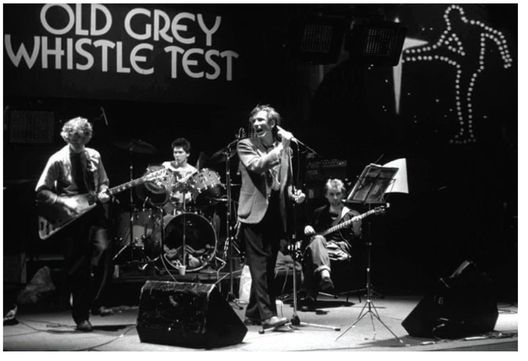

‘Careering’, along with ‘Poptones’ was then performed on BBC-2’s long-running Old Grey Whistle Test, now thankfully wrestled from the control of the somnambulant Bob Harris. New presenter Annie Nightingale called the PiL session the most powerful she’d ever witnessed, while Martin Atkins confirmed his position as ‘new PiL drummer’ - the most insecure job in rock music - by pounding the skins on both Beeb appearances.

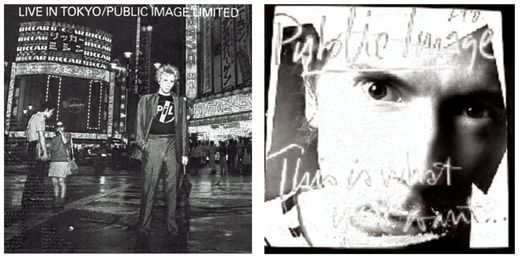

With a one-song audition, a two-song Whistle Test, and a three-song Peel session under his belt, it was time Atkins experienced PiL live. On January 17th, he appeared with the three co-founders on stage at the Palace in Paris, for PiL’s first gigs since the release of their landmark Metal Box. Both shows were being recorded officially; and reviewers were on hand to take notes.

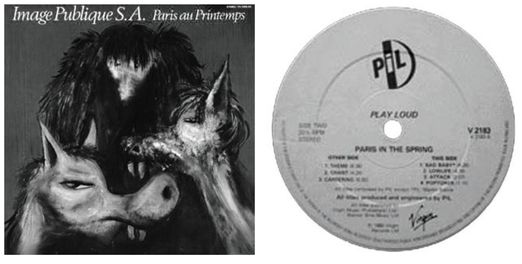

NME’s Frazer Clarke found opening night ‘an alienating performance, but if it were John Lydon’s aim to be a popular success he’d be singing re-treads of ‘Pretty Vacant’ (sic) ... We should be grateful.’ The audience was not. Despite hearing the most lengthy PiL set to date - comprising 12 songs, eight from Metal Box, with live premieres for ‘Careering’, ‘Poptones’ and ‘Bad Baby’, plus ‘Annalisa’, ‘Public Image’, ‘Attack’ and ‘Low Life’ from First Issue - Frazer Clarke confessed he’d ‘never before seen a band give an encore after having been jeered off.’ Lydon later said that the tapes used for a live album, Paris Au Printemps, required ‘some (additional) reverb to drown out the crowd booing.’ The following night, the set lasting a mere seven songs, and concluded with ‘Theme’ (which never sounded quite immense enough minus the whomp of Walker). At least Atkins would always have Paris.

“We’re just not over-eager to do live gigs; you only get a lot of thickos who just want to hear rock ‘n’ roll, even though I know there are some good people out there who want to hear good music, interesting music with subtleties and variations in it”. Jah Wobble, February 1980

With the band’s continuing reluctance to gig, it was inevitable that ‘all this forward flow’ would soon dissipate. Wobble, in particular, though towing the company line in interviews, was becoming increasingly frustrated. As an outlet for his own musical drive, he spent the early months of 1980 putting together his first solo album, The Legend Lives On, even recording enough for another mini-album, Blueberry Hill, from leftover ideas. The Legend Lives On allowed Wobble to make music more akin to the rhythms of life than the soundscapes Levene liked. His use of the backing-track to ‘Another’, on his almost oriental remix, ‘Not Another’, would produce its own set of recriminations from the communications company chairman, but Wobble was unapologetic:

Jah Wobble: I (just) wanted to put a sunshine record together, but not be insulting ... I’ve got a happy side as well. I hope people tape it off Peel and listen to it by the sunny river ... It’s partly a political thing in one sense: making your stand. It’s like with PiL we have our own organisation so to speak. PiL is five people really, six now with Martin. There’s a girl called Jeanette and Dave Crowe, both of whom are involved, coming up with ideas. PiL is more than just a band; it’s an all-embracing attitude ... (But) in PiL strange things happen. You can be sitting about for four months just soaking up influences. (1980)

Reading between the lines, Wobble wanted to get back to making music. The ‘all-embracing attitude’ of others was getting in the way. At one point Wobble took Lydon aside and said, ‘John, fucking hell, mate, the best thing to do would be to trust me, listen to me, I‘m speaking sense. Fuck these guys off ... Forget all the hangers-on and let’s do this band thing properly.’ He admits now that he failed to fully read the situation, ‘I see now, in some respects, classic signs of depression. He would spend an inordinate amount of time quietly watching videos, for hours on end. I remember feeling ..., “For fuck’s sake, John, come on!”’ Atkins was equally non-plussed by the stupefying inertia at Gunter Grove:

Martin Atkins: PiL wasn’t run like a business. It would take me five attempts of going across from Willesden Green to Chelsea before I could get anyone at Gunter Grove to open the door and give me my sixty quid. And I’d spend half of it on speed before I’d got home. If it was a Thursday, I’d probably stay at Gunter Grove until Sunday. We’d all be up watching Apocalypse Now (while) speeding.

At least there was the prospect of a trip to America, which was being organized by Levene and Lydon while Wobble put the finishing touches to The Legend Lives On... in London. It was here, after all, that Lydon’s previous lot had imploded so spectacularly at tour’s end. It was perhaps time to see if PiL could do the same. To sweeten the bitter PiL, their US label, Warners - who had passed on First Issue - had agreed to release Metal Box as a double-album called Second Edition, albeit begrudgingly:

Keith Levene: Second Edition was the Warners release. They said, “Forget any metal box, don’t even go there ... Who do you think you are? You’re lucky you’re getting a cardboard box!’ (PSF)

Lydon and Levene had flown to San Francisco at the beginning of March, as a promotional exercise coinciding with the US release of Second Edition, which received plentiful praise from Greil Marcus in his two-page Rolling Stone review. The pair also gave a press conference in a San Franciscan disco/new wave club called The City, which proved no less surreal than Dylan’s, legendary San Francisco press conference fifteen years earlier.

If the US press found it hard to grasp the fact that PiL were not a rock ‘n’ roll band, Levene went one step further, denying that PiL were even musicians: ‘Our music’s got basic structure but it ain’t music, ‘cos I don’t use chords on a guitar. Wobble does sing notes on the bass. They amount to sound. I do sound on a synthesizer. We use rhythm tracks for the drums. It’s just different. It just isn’t music... ’ Lydon decided to join in with the fun:

John Lydon: We don’t make music - it’s noise, sound. We avoid the term ‘music’ because of all those assholes who like to call themselves musicians or artists. It’s just so phony. We don’t give a shit about inner attitude, just as long as it sounds good. We’re not some intellectual bunch of freaks. I think we’re a very, very valid act. For once in a lifetime a band actually has its own way, its own terms - that would really make extreme music. We just want to make sure you have a choice. I mean, we can only be hated on a large scale.

Asked about a possible PiL tour, Lydon became impatient: ‘We’ll be doing occasional gigs, according to our whims and fancies. This is one band no one dictates to - ever. No routines.’ Inevitably, though, most questions centred on The Sex Pistols:

Q: What is the connection between PiL and The Pistols?

A: There is no connection. The Pistols finished rock ‘n’ roll. That was the last rock ‘n’ roll band. It is all over. It’s (in) the past.

Q: Why if the band is so contemptuous of the media did they consent to this press conference?

A: We need to promote our records. There is no point in hiding in closets and being arty. It is essential that everybody is aware that this band exists, because there is no competition. And I’d like that to be made very clear.

A handful of ‘in-person’ interviews were subsequently conducted at the Continental Hyatt Hotel in LA, to sympathetic journalists. Mikal Gilmore, rock journalist and brother of notorious murderer Gary Gilmore, there on behalf of Rolling Stone, asked Lydon what he thought of the endless questions about Lydon’s previous band. He got the PiL manifesto in one sound-bite, ‘All I can say is that Public Image is everything The Sex Pistols were meant to be - a valid threat to rock ‘n’ roll. In the end The Pistols weren’t any more threatening than retreaded Chuck Berry.’

Because their first album hadn’t been issued by Warners in the States - something that, in Levene’s opinion, ‘really fucked up our momentum’ - Levene and Lydon were determined to emphasise the accessibility and danceability of PiL’s music. Lydon, in particular, displayed a deep distrust of the critics, and was keen to downplay the reams of good press that had come PiL’s way in the past six months:

John Lydon: Now all the critics love us. I don’t trust all these people who praise us now. They’re the same ones who waited until The Pistols were over before they accepted them ... I think our cause will be lost (too), but that won’t be so bad.

Wobble and Atkins joined the other two on the east coast, in the middle of April. Though not booked to play night after night, they had arranged at least nine dates, spread over three weeks at the end of April and the beginning of May, in major US cities: Atlanta, Chicago, Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Detroit, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. Though it doubled the tally of PiL gigs to date, it was still not what their American label, Warner Bros, had had in mind. According to Lydon, their idea of a schedule was ‘something like 60 days non-stop gigging in very, very small clubs ... cover(ing) every single possible part of America.’

PiL’s first show - at The Orpheum in Boston - would be their longest ever gig. As with the first Paris show, they played through four months of road rust by performing everything they knew, excluding only ‘Religion’ from the full PiL repertoire. Aside from most of First Issue and Second Edition, PiL also featured ‘Home Is Where The Heart Is’, a song new to the live set, though it was something they’d been playing with for a while. The Boston show had been prefaced by two radio interview/phone-ins, both affairs being fairly good-humoured, though the WBCN broadcast largely consisted of the band abusing anyone foolish enough to phone in.

However, cracks in the ‘public image’ were becoming visible. At the end of this first US show, Wobble and Atkins played an instrumental continuation of ‘Bad Baby’ which did not appear to be rehearsed. According to Subway News, ‘After Levene eventually stamped off stage in prima donna fury over the Orpheum speakers, and Lydon followed him to thrash things out collective style, Wobble allowed himself to have some ordinary fun with the crowd, mugging like a comic-book gangster and doing a little strutting, smiling and waving.’

Keith Levene: With me and John, we had this thing if we’d start a number and it just wasn’t working, we’d stop. And then he’d do it again or do something else. The audience didn’t much care, though sometimes we’d (have) really rowdy audiences, and we’d just wind them up even more. At this particular gig, they were just watching and taking it all in. It was just very, very flat ... Somehow John and I, at the same time, just had it with this fucking gig. I stopped by hitting my master power switch and turning everything off ... John just gave me a nod and we walked off ... So we stopped, and we’re behind the stage and they’re (still) playing. I said to John, ‘I wonder how long Wobble’s gonna do this?’ (PSF)

These spring shows proved a memorable introduction to Brit post-punk for many US fans still catching up with the elements of punk interested in progression. Indeed, it is a great shame that the official live album PiL issued at the end of the year was from the lacklustre January shows, rather than one of the US shows - indeed, the live album was prompted by the release of the far more satisfactory double-bootleg, Profile from the May 5, 1980 Los Angeles show. The New York gig, two days after Boston - filmed and recorded professionally - could easily have been issued as both a sell-through video and an album. For PiL fans back home an enthusiastic review of the gig in question, in NME, suggested that they were missing out on some punchy performances:

‘The show does defeat the expectations of a rock band performance in many ways: their approach to pacing is neither the classic strong start, slow down, big build-up-at-the-end scheme, nor the punk pull out all the stops approach. Instead there are long lulls when the music almost becomes a monotonous flow; then comes the peaks, redeeming everything - not through virtuosity, but through daring.... After a while, Lydon starts bringing kids up on-stage to be guest vocalists. When a crowd of nine or ten punky-looking kids has massed, he hands a music stand and lyric sheet to one of them and joins the kids in the crowd onstage, just bopping around, grinning broadly. Tonight, his plan to share the stage with his audience causes the set to finally self-destruct - a conclusion which to PiL is probably more than acceptable.’

If the New York show played to an audience for whom ‘no wave’ had already provided a reasonable introduction to horrible noise, the Los Angeles show brought its own horrors, none of them musical. When Lydon took to the stage, it was to an audience the like of which even he had never encountered. As Mikail Gilmore has written, ‘Lydon was plain transfixing, but the audience that assembled to celebrate the band’s appearance, a crowd of thuggish-looking jar-head punks who eventually became dubbed the area’s “hardcore” subculture, very nearly upstaged the show. It was the first time this audience had made its identity felt in such a large, collective and forcible way.’ Slash editor Claude Bessy, who had done so much to push the punk revolution there in L.A., also sensed a parting of the ways:

‘The kid is lifted to the stage and John starts whispering in his ear (no doubt professional tips on stage presence) while handing him a notebook of lyrics. The song is ‘Bad Baby’ and soon the ‘don’t you listen’ chorus is being sung by the new vocalist over and over again, first with John and then alone. The hecklers, the fans, the spitters - everyone is standing, at a loss for an appropriate response. John sits grinning by the drum set, puffing on a cigarette, while the rest of PiL endlessly repeat the riff. The spitting has stopped, this substitution of targets being after all very upsetting and most unlike the way things had to be. And to the dismay of a mob that can’t wait for the various roles of star and audience to be reinstated, so they can go on being idol and fan, things don’t go back to normal ... Lydon skanks, laughing, enjoying this holiday, spots a clinging figure to one side and helps a second junior punk to the stage. Number two understands the new game and immediately struts about giving the finger to his mates, spitting on top of their heads and arrogantly skanking and weaving in the Huntingdon Beach Downhill Racer fashion. Two more minutes and a third edition who specialises in the worm style of dancing, the three extras taking turns banging on Keith’s synthesizer. Lydon announced, “That’s it, we’ve had enough”, and bids farewell to Los Angeles.’

For all his debunking of punk, Lydon remained in command. As Kristine McKenna wrote in her Rolling Stone review of the show, ‘What a show it was. The music was immense and primitive, the crowd was horrifying, and Lydon was staggeringly in control every second.’ Lydon was determined to articulate his performance aesthetic (because that’s what it amounted to). For him, it should always be ‘free form. We decide what songs we do as we do them, as we’re inspired. I couldn’t bear a fuckin’ format.’ He also insisted on an element of positive audience participation.

During their LA sojourn, Sounds’ US correspondent Sylvie Simmons asked Lydon whether he shouldn’t be offering something more to the audience: ‘In other words dictate? No. I merely offer my point of view and Wobble offers his (my italics); and you either appreciate it or hate it, simple, but don’t slavishly idolise it. I’m not saying I’m totally right.’

That Lydon and Wobble were at odds with their respective approaches was no longer such a closely guarded secret. All this talk of spontaneity disguised deep divisions in the PiL camp. Wobble, in particular, thought that it had become an excuse for not rehearsing, not working at what they had. If he generally kept his thoughts to himself Stateside, even when a participant in radio phone-ins, after his departure from the set-up he portrayed this American visit in terms clearly critical of Lydon and Levene:

Jah Wobble: The gigs in America, playing for 20 minutes and getting into this corny audience conflict situation – it wasn’t leading anywhere. A performer has got a responsibility, especially in ritual music like PiL played. It’s give and take. (1982)

After the LA performance, PiL headed on to San Francisco for their final two US shows, at the Oakland Coliseum and San Francisco’s Market Centre. The day of the last US gig the band again participated in a phone-in, on San Rafael’s KTIM radio station. By now the image had clearly cracked, if not for Wobble, certainly for their disillusioned drummer. To the acute embarrassment of Lydon, Martin Atkins took the opportunity of KTIM’s live radio programme to launch an attack upon ‘the PiL attitude’. Asked about the solo single that he had recently recorded as Brian Brain, he let rip:

MA: I just wanted to do something that was slightly professional.

DJ: Are you implying that the work you do with PiL is not professional?

MA: Yes. I would call it unprofessional. I would call it the emperor’s new clothes.

Lydon: Go on, Martin. Keep waffling.

MA: We are the emperor’s new clothes but no one is saying that we are. We are it.

DJ: Is Johnny the emperor?

MA: No, nobody is the emperor. We are it. I’m just waiting for some fucking asshole to say that we are not wearing any clothes. I just wish somebody would have the fucking guts to do it.

DJ: What makes it unprofessional?

MA: The attitude behind it. The promotion. Lack of management.

DJ: You manage yourselves?

MA: We don’t manage ourselves. We mismanage ourselves. Lydon: Are you still waffling?

MA: Before a gig we unsynchronise our watches, which is the whole crux of it. We cock-up everything there is to cock-up. We constantly underachieve.

Lydon (in childish voice): Can you put a record on, now, now, now?

Later on in the show Lydon refers to Atkins as ‘the embarrassment of our little group’; but Atkins is no longer cowed, ‘Yeah, ‘cause I’m professional.’

Not surprisingly, Atkins was given the boot - for the first, but not the last time – on their return to Blighty. According to Atkins’ own statement, ‘Jah Wobble might be leaving the group as well.’ A Virgin statement insisted that Wobble was still very much part of the organisation, but Atkins was ‘not working with the band any more as they don’t need a drummer, because they’re not gigging any more.’ The statement went further, depicting the PiL organisation as ‘very much alive... (and) working on other visual and aural projects, the fruits of which will be seen and heard shortly.” It was the same righteous blather they had been spouting for two years now.

Whatever the official Virgin line, PiL the band was clearly self-destructing. The statement that they would be playing no more gigs was probably the last straw for Wobble. When Levene and Lydon again flew out to the States, at the end of June, to discuss a possible film soundtrack (first mooted during their previous visit), and to appear on NBC’s Tomorrow Show, compered by Tom Snyder, Wobble decided to leave them to it, and get back to making music. Wobble’s rift with Lydon never entirely healed, and their years of friendship came to an unpleasant end. Looking back on his departure, a couple of years later, Wobble had this to say:

Jah Wobble: Public Image was always Rotten’s vehicle. I figured that out. It took about nine months for me to decide to leave and it was finally because I couldn’t stand the pretentiousness of it all... It was supposed to be an umbrella organisation, which it never became. The video, our own label, none of that ever happened. I started to feel embarrassed. (1982)

Wobble promptly recruited old PiL drummer Jim Walker for a new band called The Human Condition, with a view to developing some of the ideas left still-born by PiL after the brave new world of First Issue and Metal Box. Meanwhile, Lydon was telling Snyder that he considered gigs nowadays to be ‘a bunch of gits on a stage with all these idiots standing in the pits worshipping them, thinking they’re heroes. There should be no difference between who’s on stage and who’s in the audience. And we’ve tried very hard to break down those barriers but it’s not working... (weary tone) So we have to think again. In the meantime, we’ll put our attention somewhere else.’

The Tomorrow show exchange started out a bad-tempered affair, and got worse, with Snyder prodding and poking, but continually being blanked. Lydon seemed determined to put Snyder down, even when he asked a perfectly sensible question; while Levene just sat there pin-eyed – pilled to the gills, or jet-lagged, or both. When The Pistols were mentioned, Lydon stage-whispered, ‘I wondered when you’d get to that.’ During the commercial break Synder apparently exploded: ‘What the fuck are you doing? You’re making a fool of yourself.’

Lydon later contended that he’d been set up, but his boorish behaviour on national TV was not well-received by American press and public alike. Rolling Stone reported that, ‘Snyder, for once, was right on the mark,’ for calling Lydon a ‘fucking fool’. So, not a particularly successful exercise in the art of communication from this so-called communication company. And yet the whole exercise in mutual incomprehension has come to be seen as a classic clip, a confrontation celèbre. Indeed, when Sony recently released a DVD compilation of Snyder’s New Wave guests, it was given prominence in all the accompanying blurb and artwork.

But there was disturbing news from home. And so, the day before flying to New York - for further ‘meetings’ – Levene organised an interview with NME, intended to abate mounting speculation over the band’s future. The front-cover of the paper still bore the headline, ‘The PiL Corp to cease trading?’, suggesting that editor Neil Spencer was unconvinced by Levene’s rambling justifications of the way that PiL seemed to haemorrhage members. Levene again mentioned his desire to do the musical soundtrack for director Michael Wadleigh’s forthcoming film, concerning the ‘similarities between wolves and Red Indians -their outsider sensibilities, pack hunting and instinctive behaviour.’

Keith Levene: I met loads of guys in America who spoke about PiL, but he (Wadleigh) was the only one who knew what he was talking about. He’s the only one who could pick up on those 32 levels ‘of different things you can get off in PiL music…’ I was talking of earlier; he could pinpoint and talk about them on certain tracks. He offered us a third of the soundtrack and I hope that we impress him enough (so) that we can do all of it. He wants us in our music to possibly find sounds for what a wolf sees and hears and smells when it sees a human and so on. We might just end up doing vocal sounds through John and treating them.

Though he could not read music, and had no experience of scoring a film, or working to a schedule set by the studio, not the twilight world he increasingly inhabited, Levene remained optimistic about the project. But the mention of Wobble prompted an attack on his extra-curricular activities, using the (oft-quoted) charge that the bassist had misappropriated PiL backing tracks for his solo album:

Keith Levene: We can all do solo work, yeah, but it comes under PiL, not Jah Wobble. We always knew that Wobble was making the record, but we didn’t know anything about it, so I don’t see that it connects with PiL at all – whereas I see any of the stuff I do as always connecting with PiL. The thing that Wobble did was a mercenary act. I didn’t like him using backing tracks from PiL that I didn’t want people to hear. (1980)

Yet Wobble was not replaceable, and even the terrible twins recognised this. Levene and Lydon chose not to try, though they were unclear about how the communications company could maintain any kind of public profile without a rhythm section of any description. For now, their immediate recourse – both to maintain that public profile and to fund future ventures – was an industry cliche: the stop-gap live album.

With no studio album on the horizon, they decided to provide a potted history of PiL the occasional live band. Lydon was quick to point out that the release of Paris Au Printemps – on the first anniversary of the release of Metal Box - was essentially an anti-bootlegging exercise: ‘It’s a hell of a lot cheaper than the bootleg and much better quality – that’s it.’ However, this was no budget release; despite marginal production values, and the fact that just seven of the thirteen songs performed at the two Paris shows were included. The alternative – a more ambitious audio-visual package from the New York show in April – just seemed to require too much effort from two souls increasingly disconnected from the world at large; in Lydon’s case, because of undiagnosed depression; in Levene’s, the result of persistent drug use.

The reviews of this thin live album certainly gave concerned critics an excuse to vent on the unfulfilled potential of PiL, thanks to the sheer mundanity of the issued item. The review in Sounds, coming from the man who praised Metal Box to the skies, Dave McCullough, was all the more damning for his displayed disappointment, ‘An album of blank noise would have said more about PiL, been more redeeming than this lifeless lump of rehashed vinyl. ’ Ex-Sounds correspondent Vivien Goldman – now defected to Melody Maker - remained close to the band but still couldn’t help commenting on ‘Wobble’s steady bass, teetering on the brink of nimble jazz runs’, before proceeding to ask the $64,000 question ‘raised by the Paris Au Printemps time capsule... What will PiL be minus Wobble?’

And yet, it was the one positive review of the album – Lynden Barber’s in the same paper, which called these soundscapes ‘dangerous nightmare music that’ll make you worry, lifting the stone of normality to find the dirt lurking beneath’ - that drew Lydon’s ire. Commenting on this review to Goldman, he said, ‘Well, that’s enough to turn off anyone. I mean would you buy a record that promised to sound like that?’ Maybe he was embarrassed by any praise for such obvious product. Yet when it came to filthy lucre he had no shame. As he wrote a couple of months later, ‘At the moment PiL’s financial situation is desperate. But there are all kinds of ways of making money dear boy. Hustle, hustle, hustle.’

While Levene searched for a possible future musical direction that could be achieved without a rhythm section, Lydon elected to join his brother for an October weekend in Dublin. Though it was expected that the odd pint of Guinness might be consumed, Lydon couldn’t have envisaged that he would spend the weekend in Mountjoy Prison, charged with assaulting a pub owner and his assistant. Lydon, who later claimed that he had been considering moving PiL enterprises across the Irish Sea to avoid harassment by petty officialdom, found that he was just as great a target in the not-so-quiet land of Erin.

Lydon claimed he had wandered into the Horse & Tram pub on October 3 with an anonymous fan, who had offered to buy him a drink. After being refused service, the landlord alleged that Lydon became abusive and physically assaulted the pub’s owner and assistant – both of whom were ‘seven foot tall and six feet wide’, according to Lydon. Lydon’s own account of the incident directly contradicted the testimony of Tweedledee and Tweedledum:

John Lydon: This man asked me for an autograph out in the street and offered me a pint of beer. Well, we went up to the bar and asked for two pints of lager and were told ‘no’. When we were told to get out, I asked him, Why, was I black or something? He just told me to get out. Then, when I was walking out I got smashed in the back of the head... I have never been in any sort of affray like that. (1981)

After a District Court judge, Justice McCarthy, turned down three pleas for bail on Saturday morning Lydon was forced to spend the whole weekend in Dublin’s notorious Mountjoy Prison. On the Monday afternoon he was peremptorily sentenced to three months in jail on the hearsay of two Dubliners of dubious provenance, at which point a Virgin representative produced the necessary bail, pending an appeal against the decision, to be heard in December.

The affair contributed to Lydon’s increasing sense of disillusionment with life in the British Isles. Though insisting he would not write about his weekend in jail – ‘That would be too corny. How could I write about me like that? Who would want to listen to me whining in self-pity?’ – ‘Francis Massacre’ on the next album, ostensibly about the life sentence given to Francis Moran, retained as its refrain, ‘Mountjoy is fun/ Go down for life.’

At the beginning of November, Lydon and Levene headed for Virgin’s Manor Studios in Oxford to start work on the follow-up to the monumental Metal Box. Everyone was waiting to see where they went, without Wobble. Though supposedly there to record some demos with producer Mick Glossop, they had no finished songs to demo, just ideas, fragments, lines that they hoped might evolve sponaneously, just by setting up in the studio:

Keith Levene: (Initially) it was just me, John and Jeanette in the studio. We were booked into The Manor for 10 days and it was like we knew we were doing a new album, and we couldn’t do anything for days – we couldn’t do anything. It was like this horrible mental block... We’d turn up there and go through the process of setting up the instruments. And nothing was happening. Nobody was doing anything. It was the third day we were there and still, nobody was doing anything... By the fourth day, I set up this really fucking weird situation in the studio where we’ve got these 36 channels in and I’m using eighteen of them for the drums and this weird bamboo instrument I had set up in the drum booth. I was just on a high-energy pitch and said, ‘We got to record something! I’m going into the fucking drum room, we’ll do a quick mic check, then I want you to just put me into record.’... So I made that tune ‘Hymie’s Hymn.’... I had been offered to make this film soundtrack for Wolfen... I came up with ‘Hymie’s Hymn’ as my pilot for the score for the movie. (1981/PSF)

Levene had spent the first two days at The Manor trying to redo ‘Home Is Where The Heart Is’, using a loop of four notes to replace Wobble’s original, more melodic bass. Though the song ended up as the B-side of the ‘Flowers Of Romance’ single, this was an exercise in treading water. Finally, Levene made the call to Martin Atkins.

Martin Atkins: I was excited to hear what they had done in the preceding two weeks up there – NOTHING! I dove in and worked on a few rhythms, Mickey Mouse watch loops etc., for ‘Four Enclosed’, trumpets from this little battery powered trumpet thing that played 3” plasticdiscs etc.

Three songs featuring Atkins were recorded – ‘Four Enclosed Walls’, ‘Under The House’ and ‘Banging The Door’ – at the remaining Manor sessions. According to Atkins, talking in 2004, ‘John also told me recently that I performed (and co-wrote) the ‘Flowers’ track - I just let all of these ideas flow, then left them with the ideas and went off to tour the USA.’ Still some way short of an album, sessions continued at Townhouse Studios in West London. Chris Salewicz, sent there to interview Lydon and Levene, described the scene that greeted him:

‘John is hunched over a 32-track mixing desk that dwarfs his slight, unexpectedly studious figure. He is mixing PiL tracks recorded the previous day for a new studio album. Between takes, from time to time, he peers up at the television that is set in the wall above his head.’