Time Loves A Hero: The Fury Returns

Four years ago, on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the release of the Sex Pistols’ ‘God Save the Queen’, I wrote a provocative article in The Guardian - a ‘think piece’ in newspaper parlance - questioning the historical significance of the punk explosion in the annals of popular culture. From this brave, if not foolhardy, messing with the cherished memories of a generation, a mischief-making sub-editor then extracted the article’s most inflammatory phrase and came up with the eye-catching, tabloid-style headline: ‘FACE IT: PUNK WAS RUBBISH’. Underneath there ran a somewhat more reasoned expression of the article’s central contention, with a strapline that read: ‘Sure, it had energy and attitude. But punk’s importance has been hugely exaggerated, says Nigel Williamson.’

But the headline had done its job and it brought down a torrent of anger, abuse, and metaphorical spittle upon my head. I make no complaints about that. The piece had been intended to provoke a debate but I didn’t realise just how virulent it would get. I suppose I should have taken more notice when the paper happily predicted that I would get crucified. ‘This will keep the letters page busy for a week,’ my commissioning editor told me approvingly.

He had underestimated. I was roundly denounced and abused by the paper’s readers for the next two weeks. Then it got silly. Someone wrote in to say that nobody with a name like Nigel could have ever made a credible punk, and somebody else then wrote in to wonder where this left XTC’s ‘Making Plans For Nigel’. At this point the letters’ editor wisely declared the correspondence closed, although it continued to rage for months on various websites and message boards, where calls for me to be hung, drawn and quartered - or worse - appeared with alarming passion and worrying regularity.

Someone even wrote to the editor of Uncut, another title for which I work regularly in a freelance capacity, demanding that I never be allowed to appear in the pages of the magazine again, and threatening to organise a reader’s petition if I wasn’t banished forthwith. On the other hand, there was also some support. Several prominent fellow hacks emailed to commend me on my ‘guts’ (which I took to mean they probably agreed but weren’t going to say so in public) while one reader wrote to express appreciation that someone had finally taken on ‘the Stalinist/NME view of musical history’.

When asked to revisit the debate for this book of essays, my first act was to look up that original, notorious article from 2002. In describing it as ‘notorious’, I hope I’m not guilty of self-aggrandisement here. But in the four years since the piece first appeared, I would estimate that I’ve been reminded or asked about it at least once a month. Like Siouxsie’s swastika or The Rolling Stones pissing up a garage wall, it was a social faux pas which in certain quarters shall never be forgiven or forgotten.

The original piece, of course, was written in a racy, polemical style, deliberately geared to get a rise out of readers, so inevitably it represented a simplified and short-handed version of my views. But in reading it again, I can’t really say that I would wish to disown anything I wrote, even if I might have expressed some of the more contentious views with greater diplomacy. With apologies to those who read it at the time (and no doubt reacted as angrily as I’d intended), this is a summary of the argument.

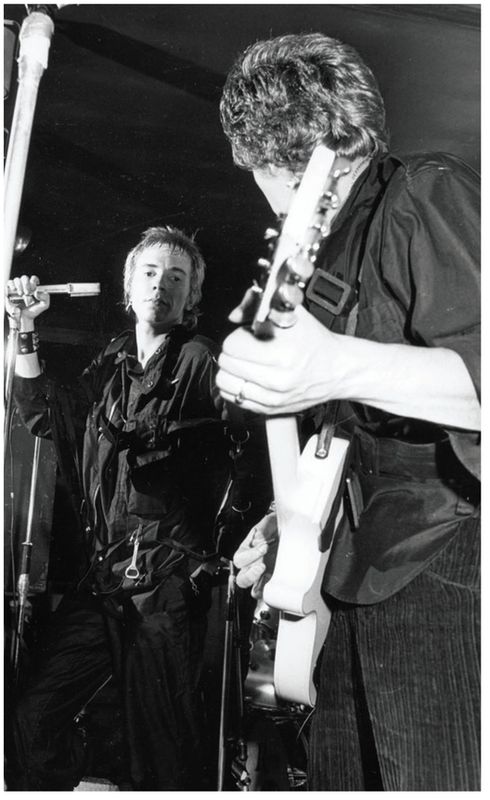

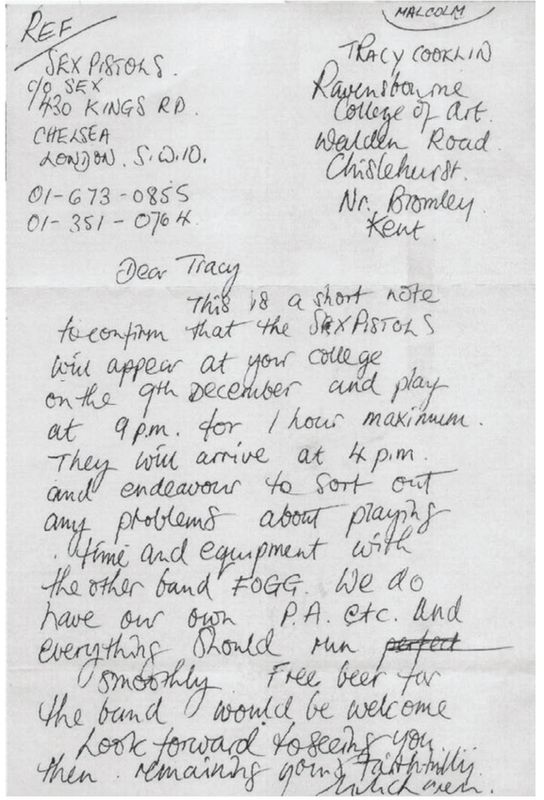

I saw one of the Sex Pistols first gigs on a cold and cheerless Saturday night in December 1975. We were drinking in Henekey’s Wine Bar, on Bromley High Street, and wondering whether we could be bothered to move the short distance to Ravensbourne College of Art to see a band nobody had heard of, or whether to stay put and get steadily drunk. In the end, we went and paid an entry fee that I seem to recall was 50 pence. Within minutes of the band taking the stage, we wished we’d stayed in the pub, for there seemed more future in getting mindlessly obliterated on pints of Newcastle Brown than in listening to such a racket.

The Pistols could barely play their instruments. Each tuneless thrash that passed for a song sounded the same as the one before. While the spotty, undernourished front-man knew how to sneer, he certainly didn’t know how to sing. I don’t think we bothered to stay until the end and after retrieving our Afghan coats from the cloakroom, we shuffled off into the night, back to our squat to skin up a spliff and listen to the new Little Feat album.

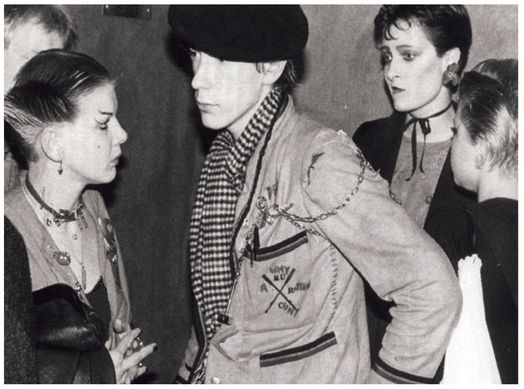

Not everyone who was present that night shared our dismissive judgement. Also in attendance was 18-year-old Susan Dallion. She and her mates decided they had witnessed the future of rock ‘n’ roll and went on to form punk’s notorious chapter, ‘the Bromley contingent’. It wasn’t long before Dallion was fronting Siouxsie & The Banshees, one of the more imaginative and interesting bands to emerge from the punk scene.

We thought no more about the Sex Pistols until a few months later when we set off to see a great little pub rock outfit called Roogalator at the 100 Club. When we arrived, they had cancelled due to illness and the replacement was a band called The Jam, playing one of their first London gigs. They were even worse than the Pistols and we asked for a refund. I’m sure we got our money back too.

Yes, you could say I never really got punk. I was 22 years old in 1976 - younger than Mick Jones and Joe Strummer and the same age as Elvis Costello - and by rights I should have loved punk’s iconoclasm. Instead, I hated its lack of imagination, its absence of musicality and its empty nihilism. Yet today, it has become heretical to point out that punk actually wasn’t very good.

Rotten with ‘The Contingent’, Siouxsie second right.

I still go to gigs and talking to younger fans am frequently told how lucky I was to have been around during the punk era. I don’t have the heart to tell them how truly awful most of it was. Sure, it had energy. It had attitude. But so does a pub-side full of no-hopers playing soccer on Hackney Marsh every Sunday. The honest truth is that the reverence in which punk is held some 30 years after it first rattled the bars of youth culture is based on a series of myths and misconceptions.

First: it is now received wisdom that by 1976, popular music was so complacent, self indulgent and moribund that punk was a reaction that had to happen. True, we could have done without the tedious triple live albums from Emerson, Lake and Palmer. Alongside this the pretentious gatefold concepts of Yes, and such boring old farts as Barclay James Harvest, probably deserved to be swept away. But punk threw the baby out with the bath water.

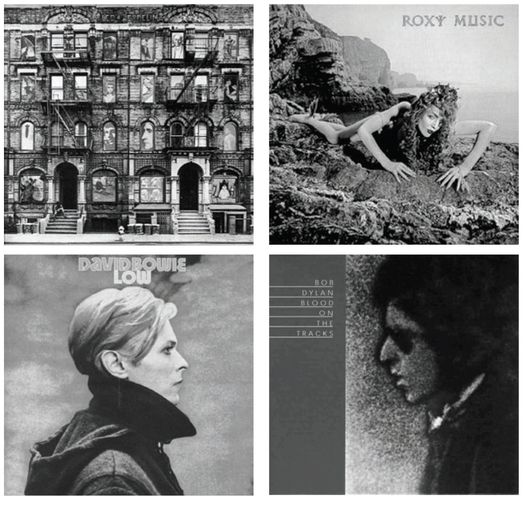

You’d never know it from the punk version of musical history, but the mid-1970s were actually a golden period for rock. David Bowie released Low, Roxy Music made Siren and Led Zeppelin produced Physical Graffiti, the heaviest album of their career. In America, Bruce Springsteen had just released Born To Run, Dylan had returned to form with Blood On The Tracks and Tom Waits was finding his boho voice on albums such as Nighthawks At The Diner and Small Change.

Second: punk, they say, was responsible for launching the most prolific crop of great bands since the 1960s beat boom. Really? The Sex Pistols made one studio album - although admittedly this did turn out to be an all-time classic. The Clash made a handful of great records and Siouxsie had a certain style when she got over the swastika. But can anyone seriously claim that Sham 69 or Slaughter & The Dogs have stood the test of time? Of course there was Ian Dury & The Blockheads, but the great man was in his mid-30s by the time punk came along and had, by 1976, been peddling his inspired songs for half a dozen years in Kilburn & The High Roads. Only that was called ‘pub rock’ and we were meant to despise that, weren’t we?

Third: we are asked to believe that punk not only rescued rock ‘n’ roll from its deathbed, but also gave birth to the ‘new wave’. In fact, the so-called new wave happened not because of punk but despite it, as those who could write proper songs and had some genuine musical ability began to reassert more traditional values. Elvis Costello may have astutely adopted some of the ‘fuck you’ attitude of the era, but he always knew more than three chords and hardly needed the example of Johnny Rotten and his ilk to make albums such as My Aim Is True and This Year’s Model.

Fourth: we are regularly reminded that punk ensured music would never be the same again. In fact its influence was largely ephemeral. By the end of the 1970s, punk’s self-styled barbarians at the gate had exhausted themselves and pop music went back to its same old ways. Only some of it was even worse as the 1980s were drowned out in tinny synthesizers and boring drum machines programmed by men with risible perms. What of the old farts the punk hordes promised to consign to the dustbin of history? They just go on and on as if nothing ever happened.

Then with a rhetorical flourish, I appended the infamous final paragraph that gave the piece its eye-catching headline: ‘Let’s face it. Punk was rubbish. But perhaps that was the point. It was always meant to be.’

It was controversial stuff and trenchantly expressed to be sure, and the reaction was as swift as my commissioning editor had predicted. To be fair, much of the debate that ensued was intelligent and informed. Harvey Johnman from London was the first into print. ‘Nigel Williamson’s vision is still obscured by his joss sticks,’ he wrote. ‘The best bands that followed all took their call from punk: Wire, Gang of Four, Joy Division. The fall-out is still happening, from Nick Cave to Nirvana, Primal Scream to Leftfield, the most exciting and original rock and dance artists, all sparked by punk, continue to fight the cause. Face it, with his Afghan coat in 1976, Nigel was really too old to get it.’

James Martin Charlton, another London reader with a clearly utopian bent, then tried to claim that it had been perfectly possible to like both punk and traditional rock in 1977. He clearly wasn’t around at the time, for my recollection is that you’d actually have been safer wearing a Spurs shirt to a match at Highbury than turning up to a punk gig with long hair and an Incredible String Band album under your arm. ‘It wasn’t against the good things Nigel mentions - Springsteen, Dylan, Led Zeppelin,’ he insisted. ‘It was for artistic expression, kicking open doors and expressing bliss in sharp bursts.’

Then - shock horror - a brave chap called Paul Flewers wrote in to agree with me. ‘Punk was awful. Apart from its musical ineptitude, it was deeply misanthropic. Its anti-authoritarianism was that of the yob who spits at anything of beauty, subtlety, and genuine humanity,’ he blasted. That wasn’t really what I had meant at all, but thanks for sticking up for me anyway, Paul.

More measured support came from David Ash, an ex-pat who emailed The Guardian all the way from Singapore. ‘I was 18 at the peak of the punk movement in 1977 and was caught up in the whole idealism and music at the time. But there came a point when a bell rang in my head that caused me to stop and take a closer look at the whole sorry mess,’ he reasoned. ‘I’m not sure what caused that bell to ring but I have a feeling it was the start of 1978 and an article in Sounds about The Damned being the future of rock ‘n’ roll. Huh? I remembered them playing Croydon Greyhound two years earlier and thinking they were a reasonable pub band. Was this the same? The future of rock ‘n’ roll? Did I miss something? Sadly, yes, and to see them in 2002 reforming to tour again with god knows who in the line up makes me glad I moved 6,000 miles away. Every month I look at Q magazine and I see who’s reforming/playing. Siouxsie, Buzzcocks, Pistols, UK Subs (did they ever go away?) and I shake my head. I can maybe, just maybe, understand the Pistols getting back together for a gig for the Jubilee but the rest of them sound like one of the those 60s revival tours with The Hollies and The Drifters. What next? The Lurkers at Pontin’s? Nigel, you were right, most of the bands were shit but the attitude was the order of the day and that was the most important thing.’

I also enjoyed this response from Bob Kemp who brilliantly managed to articulate his teenage passion a quarter of a century earlier: ‘In 1975 I was 13 and punk was nibbling its way into the provinces in the shape of a school weirdo whose name was Kev. He dressed in a mac, had dyed hair and oddball make-up. Meanwhile the charts were full of disco like - The Real Thing and similar works of the devil. Guitars were played without distortion. When the Pistols were(n’t) on Top Of The Pops the clouds cleared (they were filmed in some echoing hall, well away from the BBC no doubt). A moment of catharsis equalled only by Otway and Barrett’s power chords and yowling vocals. Happiness was a warm fuzz box. Two chords could be an elegant quip. The Pistols produced one good album – who cares who played on it or how overdubbed it may have been? Punk wasn’t the sound of the suburbs – it was the sound of a tinny TV speaker, of your dad’s stereo when he’d gone to do his dinner party duty, of a tape from the radio with plates clanking in the background, of a song you couldn’t hear ‘cos no-one would play it. The rock ‘n’ roll dream Nige, geddit?’

Mike Nelson emailed the letters editor with another intelligently argued response. ‘Nigel Williamson misses the point by a greater distance than John Lydon could spit,’ he began, before going on to point out – quite correctly, I am forced to admit – that ‘Tom Waits could have released a wonderful album once a fortnight without ever affecting the lives of Britain’s dissatisfied youth.’

Costello, he claimed, was not a typical example of those who rode to prominence on the crest of punk. ‘Try instead The Stranglers, XTC, Blondie, The Boomtown Rats, The Police. Without punk, none of these bands could get past the front desks of a record company’s offices. After punk, they all found audiences amongst the young and reckless (i.e. not 22-year-old, Afghan-wearing, Little Feat fans).’

Someone styling themselves ‘Fred Ramone’ then wrote in to say: ‘Yes, there were good things going on in music but they were scattered, many of them underground and their appeal was to adults. What did a 13-year-old like me want in 1976 with Bob Dylan or Tom Waits? I like it now but then! I wanted energy, I wanted passion. I’d come out of loving the Sweet and Wizzard, what did I want with Little Feat?’

Steve Vanstone from Purley began by agreeing with my thesis, but subtly shifted the ground of the argument by claiming that crap music could still be great (a view with which I can only agree and which even Noel Coward recognised when he once had a character remark on the potency of ‘cheap music’). ‘Of course most of punk was rubbish and, of course, little of it has stood the test of time,’ he admitted. ‘But punk was all about adolescents making their own music very cheaply, and if they were lucky enough to get their three minutes (or less) of fame via the John Peel show, then most were happy and moved on. Punk music was instant, disposable pop but that doesn’t preclude any of it being excellent, inspiring and exciting. The world would have been a more miserable place without the likes of The Buzzcocks, The Nipple Erectors and the Snivelling Shits. So what if it was only two or three chords?’

Then, to my delight, the mighty Captain Sensible from The Damned wrote in to denounce me as a ‘berk’ (and, if you will forgive my cynicism, also to secure a free plug for the revival tour his band of punk geriatrics were about to undertake). ‘Nigel Williamson seems to have missed the point,’ he railed. ‘Punk was never just about the music – although some of it was pretty spectacular in its aggression and pure cheek. No – it was about the attitude. The ‘punks’ sang relevant songs about previously taboo subjects (republicanism, animal rights, etc) while overturning the ridiculous mid-70s ‘cock rock’ music scene with its limos, groupies and coke-fuelled sexist rock stars writing meaningless songs about wizards, pixies and the like. And for a couple of years you didn’t need to have vast amounts of cash, a flashy sports car and a wardrobe full of Italian fashion crap to be the trendiest person in town. No, even rich folk were wearing dodgy clothes from charity shops and bin liners – you had to laugh! And if you were lucky enough to be able to finish the look with a few spots and some bad teeth then you had it made. Just what was Nigel Williamson doing listening to boring American nonsense like Little Feat and Bruce Springsteen in Britain’s finest hour? Berk!’

Fantastic, I thought – there really are old punks out there who still think Little Feat are the enemy, and believe in ‘year zero’, just like those mythical Japanese soldiers still hiding in the Asian jungle not aware that WWII is over. But I took the view that I’d had my say and so never responded to any of the debate. I was more than happy to wear, as a badge of honour, the names assigned to me by a middle-aged bloke who still clung to the punk moniker he’d adopted in his early 20s. If I’d thought, there was even a great t-shirt in it: ‘Captain Sensible Called Me A Berk’.

Despite the provocative headline, my main intention had been less to argue that punk was worthless, and more to question its myths and some of its more preposterous manifestations. I was always particularly offended by the Pol Pot-style dumbness of the ‘year zero’ mentality. In 2005, I asked Kris Needs, editor of ZigZag during the punk years and fellow contributor to this collection, if such an absolutist attitude had been necessary. He admitted that today it looked foolish but still argued that it had been vital at the time. ‘I think you had to wipe the slate keen,’ he insisted. ‘The Sex Pistols did that by saying every band that had gone before was crap and Joe [Strummer] for a while wiped his slate very clean too, and wouldn’t acknowledge his past. What you have to remember is that rock ‘n’ roll was a taboo phrase.’

I still have a problem with that sensibility, and what I also wanted to explore in my original article was whether what fired punk was really much different from what fuelled any other generation finding the music of its elders outdated and dull, seeking its own new and rebellious forms of expression.

Captain Sensible

When Elvis Presley walked into the Sun Studios in Memphis in 1954 and recorded ‘That’s All Right’, he wasn’t aspiring to be a fat millionaire who would play Las Vegas. When the teenage Mick Jagger was sending off to Chess’ mail order department in Chicago for obscure R&B records, which he would then try to copy, he wasn’t thinking about a knighthood. Likewise, when Robert Plant joined Led Zeppelin, he wasn’t dreaming of becoming the god of cock-rock. Nor, and we include him simply because his band became a kind of emblem in the original debate, was Lowell George imagining stretch limos and silver coke spoons when he formed Little Feat. All they were thinking about was making music. In this, I continue to argue, such luminaries as Joe Strummer, Nick Lowe and Elvis Costello who came to prominence on the crest of punk were no different from those who had gone before them.

What’s more, had the likes of Jagger, Plant and others been coming of age in the 1970s rather than the 1960s, they would surely have been part of the punk revolution. When I interviewed Robert Plant in 2005 and asked him how he had responded at the time to those who denounced him as a dinosaur, wishing to consign his band to the dustbin of musical history, he insisted that he and Jimmy Page had both been delighted. ‘The punks reminded us of what we were when we started out,’ he claimed. ‘Punk was marvellous, especially if you discounted the lack of originality in most of it. But they were right. There had to be some spit and some sputum. You don’t always know you’re becoming remote and missing the point. You get comfortable and you think that’s it. But then again, you can’t be in the youth club forever.’

Conversely, had the likes of Strummer and company been a decade older, they would have been in bands like the Stones and Zeppelin. As it was, punk was what was happening at the time they were emerging and they rode on its coattails expertly. Yet it would be hard for anybody to claim that without punk we never would have heard of Elvis Costello, Paul Weller, Sting or Joe Strummer, or that Patti Smith, the Ramones, Blondie and Television would not have reached our ears from the other side of the Atlantic. Such talent would have blossomed in any era and the argument that, without punk they would never have got past the receptionist in the record company’s plush front office does them a disservice. However, there is probably one notable exception to this rule. Without punk, there surely could not have been Johnny Rotten – although arguably there might have been a Sex Pistols, led by Steve Jones and Glen Matlock. They’d probably have done quite well as an amiable pub rock band playing covers of numbers by The Who and The Small Faces too, for as future Pet Shop Boy Neil Tenant put it in a letter to NME at the time (albeit, inaccurately), before Sid’s arrival the Pistols were ‘three nice clean middle-class art students and a real live dementoid.’ What’s more, without Rotten’s unruly behaviour and extraordinary attitude, there probably would have been no punk movement at all in the UK, as every such phenomenon needs its icon. When rock ‘n’ roll emerged, it was Elvis Presley. In the 60s beat boom it was The Beatles. In the 1970s it was Johnny Rotten who served as the figurehead, with a charisma that the likes of poor old Rat Scabies et al could only dream about.

Rotten was also unusual, if not unique, in that he knew or cared little about musical history. He had his odd and quirky passions for Captain Beefheart, Can and even prog misfits Van Der Graaf Generator, and he was also partial to a reggae rhythm. But he didn’t really give a toss about where it all came from. By the mid-1970s, rock ‘n’ roll was already more than two decades old and had developed a powerful sense of its own legacy. Most of those forming bands – even punk bands – knew that rock music was part of a chain with roots in blues, R&B, folk and other earlier forms. Joe Strummer was so consumed by this heritage that at one point in his pre-Clash days he named himself after Woody Guthrie and would answer to no other name. Patti Smith hung out with Dylan in Greenwich Village and was 30 years old before she made her first groundbreaking album; and Costello, despite his indefensible dissing of Ray Charles as ‘a blind ignorant nigger’, was another who was acutely aware of his place as the inheritor of a rich and profound musical legacy.

But John Lydon was a different kind of animal. He despised the past. He denied its validity because all that mattered was the here and now. He wasn’t about to embrace Pete Townshend because he wrote ‘My Generation’. He had only contempt for him as the writer of rock operas. Rotten admired the New York Dolls, who had been managed for a short while by the Pistols’ svengali Malcolm MacLaren. Yet if he was aware that they had started out trying to copy The Rolling Stones (who were then hated with a rare loathing by every punk in town), he didn’t care. He was even less interested in knowing that the Stones had in turn found their sound trying to copy Chuck Berry. To Rotten, it was irrelevant that Berry begat the Stones who begat the Dolls who begat the Pistols. So fucking what? It sounded like something out of the Old Testament. Also, unlike the more musical members of the Pistols, Rotten wasn’t interested in playing covers of songs by The Who and The Small Faces. They were the past. History was bunk, every second of it, and to Rotten and his group of camp followers – including Sid Vicious – ‘year zero’ was totally for real. They knew that everything that had gone before was worthless and boring and they proceeded to trash the past at every available opportunity.

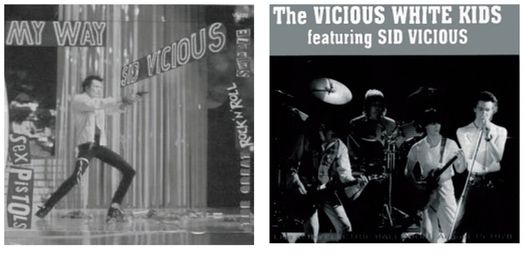

They did so verbally, but they also did it brilliantly on record, most notably in the case of Vicious’ extraordinary version of ‘My Way’. Of course, the record was trash. But it was trash of the most subversive kind. Your mum and dad hated it, not just because it was noisy and vulgar but because it mercilessly mocked their own tastes and lives. Funnily enough, the song’s writer Paul Anka came to recognise the validity of Sid’s statement. More than 30 years later, I asked him what he had made of the indignities punk had served upon his composition. To my surprise he paid tribute to the integrity of the cover. ‘At first I went “what?”’ he confessed. ‘But then I got it, because I think the guy was sincere and for him there was no other way to do it. You’ve got to respect that.’

In a way it helped that the likes of Vicious and Rotten had no real musical skills whatsoever. The latter couldn’t sing but he made a virtue out of it and he knew his talents lay elsewhere, as a controversialist. McLaren, who Tony Wilson once wickedly accused of wanting to create an outrageous version of the Bay City Rollers, may have said: ‘I was taking the nuances of Richard Hell, the faggy pop of the New York Dolls and the politics of boredom and mashing it all together to make a statement.’ But that certainly wasn’t what Rotten was doing. He wasn’t going to be McLaren’s puppet. He was just enjoying getting in people’s faces - mostly for the sheer hell of it. As he told NME’s Neil Spencer at one of the Pistols’ early gigs: ‘We’re not into music. We’re into chaos.’ Although that sounds suspiciously like one of McLaren’s lines, it also happened to be true.

For many - including Strummer and Costello who deliberately contrived to ‘lose’ not only their sense of history but their own chequered musical past - ‘year zero’ was little more than a career tactic. Others, such as The Stranglers, were even more blatant band-wagoneers. Yet for Rotten and Vicious, ‘year zero’ was both an expression of an ineffable truth and an article of faith. Consequently, it was because they believed in it to the bottom of their punk hearts that Never Mind The Bollocks remains the most potent and genuine expression of the late ‘70s punk ethos.

Despite my early contempt after seeing the Pistols in Bromley that night in December 1975 (and I would summon former Melody Maker editor Allan Jones as a witness to confirm how terrible those first gigs were – he wrote after one hapless early appearance that he didn’t think we’d ever be hearing from them again), it was the realisation that they were genuine barbarians, who really didn’t give a flying fuck, that eventually endeared them to me.

Strummer, too, realised this in what was a moment of epiphany when the Pistols supported his band The 101ers at the Nashville Rooms in April 1976. ‘The difference was we played Route 66 to the drunks in the bar, going “Please like us”. But here was this quartet who were standing there going, “We don’t give a toss what you think, you pricks…”, it took my head off. They didn’t give a shit.’

It was that quality that led me to buy Never Mind The Bollocks on its release – a rare punk purchase on my part – along with a few select singles that seemed to possess the same feral quality; X-Ray Spex’s ‘Oh Bondage, Up Yours’; a clutch of more sophisticated American ‘punk’ albums such as Patti Smith’s Horses and Television’s Marquee Moon. But I pointedly refused to buy the first Clash album. If the Pistols were the real thing, The Clash – and I know this is going to bring down a fresh round of abuse on my head from the Strummerites – seemed to me to be nothing more than posturing hypocrites.

I had seen Strummer’s pub rock band playing Route 66 and I knew his musical history. Observing him parade his new group as the most uncompromising, sea-green incorruptibles in punk’s militant army of scorched earthers just didn’t ring true. Nor did the dangerous image that the band so carefully cultivated, quite match up with The Clash who took a £100,000 advance from CBS and went on songwriting vacations to Jamaica, or The Clash who flew in American AOR producer Sandy Pearlman – on Concorde, incidentally – to oversee their Westway-inspired musical graffiti. Rotten knew it was fake too, which is presumably the reason he never liked Strummer. In fact, he once claimed the only member of The Clash he had ever been able to have a conversation with was Keith Levene, who left after only half a dozen shows and with whom Rotten would later team up in Public Image Ltd.

Strummer was also at times capable of some mind-blowingly preposterous bullshit. If you reckon that’s heresy, try this piece of arrant nonsense: ‘There’s nothing better, if you’re having an argument which won’t resolve itself in any other way, than smashing somebody’s face in’. Or this, from his first major NME interview, delivered while idly toying with a flick-knife: ‘Suppose some guy comes up to me and tries to put one over on me and I smash his face up. If he learns something from it, that’s creative violence.’

Presumably it was all part of Strummer’s striving to be a ‘real life dementoid’ like Rotten. But from an intelligent, well-educated human being who had grown up not in a squalid tower block with a broken lift but in a world of comfortable middle-class privilege, such calculated dumbing-down seemed not only idiotic and crass but cynical and dishonest. Years later, it occurred to me that such statements could actually serve as a cipher for American foreign policy post 9/11. Nobody would pretend such sentiments were clever coming from George Bush, so why should we kid ourselves that such nonsense was cool just because it came from the mouth of Joe Strummer?

In later years, via a mutual interest in world music, I got to know a very different and far more avuncular Strummer; I subsequently assisted his band, The Mescaleros, with press bios and a promotional film. I never asked him about the 1976 – 77 period, but I formed the distinct impression that he would have been profoundly embarrassed to be reminded of some of his dafter pronouncements about the pleasures of smashing up people’s faces because they disagreed with you.

The Mescaleros

Similarly, although I didn’t know Costello, I did know Jake Riviera, his manager and Stiff Records supremo. When I first encountered Jake around 1972, he was managing country-tinged pub rock hopefuls Chilli Willi & The Red Hot Peppers. As an 18-year-old, I used to follow the band around such pub rock venues as the Hope & Anchor in Islington and the Tally Ho in Kentish Town, and after he’d noticed me at gigs a few times, he introduced himself. One night when I was going to miss the end of their set in order to catch the last train back to Bromley, he invited me to stay the night at his Notting Hill flat. There we stayed up until dawn with the Willis’ guitarist Martin Stone, smoking dope and listening to country-rock albums. I distinctly remember him playing John Stewart’s California Bloodlines but I’m pretty sure he also gave Little Feat’s Dixie Chicken a spin.

Therefore, when Riviera and his protégé Elvis Costello emerged as self-appointed spokesmen for the safety pin generation, I was deeply suspicious. When I listened to Costello’s early albums, all I heard were great songs, properly played by a band which included such pub rock veterans as former Chilli Willis’ drummer Pete Thomas. Apart from a certain snarl and mannered venom in the vocals, I wondered what the hell Costello had in common with an idiotic bunch like Sham 69, getting drenched with spittle every night. As if to prove the point, four years later he was in Nashville making a country album with Billy Sherrill. This was a great move in my book, but one that only made his earlier punk posturing look phoney.

Little Feat

But if Costello and Strummer were essentially career musos, Rotten genuinely didn’t give a fuck – about record deals or anything else. Strummer’s musings about creative violence seemed to me to represent ‘attitude’ of the most transparently calculated and fake kind. Yet the Pistols’ infamous TV appearance on Bill Grundy’s show proved that their recklessness and defiance was entirely real.

Of course they were sometimes manipulated by the media savvy McLaren. But they didn’t give a fuck about that either. As long as there was a supply of booze and sulphate to keep them happy they were up for anything. However, the most revealing part of the Grundy show appearance was that it was not one of Malcolm’s stunts at all but a spontaneous outburst. Indeed, it’s been reported that when the Pistols left the television studio, an ashen-faced MacLaren wondered aloud if this time they had gone too far. ‘But the cunt deserved it,’ was the alleged riposte from Steve Jones, in a typical example of the irrefutable logic that underpinned most things the Pistols did at the time. According to our old friend Captain Sensible, after the TV appearance, the band went back to the Roxy in Harlesden, where McLaren continued to berate the band, telling them: ‘You fucking idiots, you’ve ruined everything. We’re finished.’ But while he fretted and fussed, Rotten beamed with pleasure, for he knew that even if it had finished them, it didn’t matter because immortality awaited in the ‘filth and the fury’ headlines that would greet them the next morning.

It was the ultimate expression of what dear old Captain Sensible meant in the one intelligent thing he said in his letter to The Guardian: ‘Punk was never just about the music – although some of it was pretty spectacular in its aggression and pure cheek,’ he wrote. ‘No, it was about the attitude’. The Pistols, and Rotten in particular, had front, aggression and attitude in industrial quantities. While others cleverly and often convincingly faked such qualities, like a school of punk actors, the Pistols had no need to dissemble. That’s what made them great.

It also meant that when Rotten slagged off everything that had gone before, it was hard to take offence. He hated everything pre-punk simply because it was old. That was crime enough in his book and he really didn’t give a flying fuck about tracing the music back to its roots or any of that shit. But what really cemented the Pistols as heroes in my estimation was the release of ‘God Save the Queen’ in May 1977. Workers at the CBS plant where the record was being pressed threatened to walk out because of the disrespect to Her Majesty. Radio One banned it from its daytime schedules. Record chains refused to stock it. But the more the authorities tried to bury the record, the more determined fans were to buy it - 150,000 of them in the first five days.

At the grand old age of 22 I recognised this was why I had fallen in love with rock ‘n’ roll in the first place. From the protest songs of Dylan to the ‘lock up your daughters’ outrage of the Stones, a major part of rock music for me was about sticking two fingers up at the ‘straight world’ and the establishment. ‘Anarchy In The UK’ had been a great piece of pop subversion, but I wasn’t an anarchist. Rather, at the time, I was a card-carrying Marxist and fully paid-up combatant in the class struggle. That meant I was also a fervent anti-monarchist and ‘God Save The Queen’ with its Jamie Reid picture sleeve showing a safety pin through the loathed royal visage, warmed my republican heart. It was the perfect riposte to the one million loyal subjects who lined the streets of London to watch the Queen, dressed in frightful pink, make her way, in a golden state carriage, from Buckingham Palace to St Paul’s Cathedral. Across Britain, millions more of her subjects tuned in to watch the ‘pomp and circumstance’ on television, and celebrated with their own street parties. What were they thinking? The country was going to the dogs and instead of protesting about it, most of the nation was celebrating the very symbol of everything that was wrong and fucked up about our society. I wanted to vomit and turned up the Pistols to full volume just to piss off the neighbours. Even Little Feat’s latest opus could wait.

Looking back, it’s hard to remember just what a horribly conservative place Britain was circa 1976 – 77. Racism, homophobia and sexism were rampant and the establishment was part of the conspiracy, for it wasn’t just the Pistols who were being persecuted by the authorities. In July 1977 the courts found Gay News, and its editor Denis Lemon, guilty of ‘blasphemous libel’ following a private prosecution brought by Mary Whitehouse, the self-appointed guardian of the nation’s morals via her National Viewers and Listeners Association. The charge related to a poem and illustration about a homosexual soldier’s love for Christ at the crucifixion, that Lemon published in Gay News. The prosecution behaved like something out of the Spanish Inquisition, or from the days when you could be locked up for suggesting the world wasn’t flat.

In public, the national anthem was played on every conceivable occasion. If you went to the cinema, when the film ended they played ‘God Save The Queen’ (original version). More than once I was threatened with violence for refusing to stand. But you didn’t have to be a full-on republican to find the entire patriotic atmosphere of the nation offensive. Flag-waving had been given a further nasty taste by being hijacked by the National Front and its ‘Britain for the British’ mentality.

In August 1977 I joined an anti-National Front march in Lewisham, arranged by Rock Against Racism, an organisation run by the Socialist Workers Party. The NF were out in force on the streets, too, alongside a massive police presence. The cops, inevitably, sided with the fascists and for no reason whatsoever I found myself being chased, with around fifty other perfectly peaceful protestors, down an alley by uniformed thugs from the Special Patrol Group and had to escape via the roof of a multi-story car park.

Such events certainly demanded a soundtrack and The Clash’s ‘White Riot’ was one contender:

“Black man gotta lot a problems, but they don’t mind throwing a brick

White people go to school, where they teach you, while we walk the street, too chicken to even try it

Everybody’s doin’ just what they’re told to”

Yet somehow it seemed phoney. I didn’t want to throw a brick. But I wanted to stand up and be counted and for me it was the working-class irreverence of the Pistols rather than the posing of The Clash that gave the most effective riposte to what was going so wrong with modern Britain. There seemed to be far more genuine subversion and insurrectionary intent in lines like:

“God save the Queen

the fascist regime

they made you a moron

a potential H-bomb”

By the time the Pistols imploded in January 1978, the true spirit of punk was already on the ropes and it had degenerated into a bunch of nihilist copycat bands who imposed a uniformity that was the very opposite of what punk’s DIY spirit had supposedly been about. Rotten knew this, and much has been made of his words at the band’s final gig: ‘A ha, ha! Ever got the feeling you’re being cheated?’ To me, his meaning was crystal clear. Everything in this life is a cheat. Unless you were part of the charmed circle of the establishment elite, you were cheated of your rights from the day you were born. Even when you made your protest and shouted it as loudly as punk did, someone would turn it into a product and market it and cheat everybody all over again. It wasn’t the Sex Pistols who were cheating their fans. We were all being cheated by the capitalist society in which we lived. At least, that was my Marxist analysis at the time.

Which leaves us with the disputed legacy of the Pistols and punk. My view, that after a brief hiatus normal service was swiftly resumed and the old guard carried on pretty much as if nothing had ever happened, remains unaltered. In his letter to The Guardian, ‘Fred Ramone’ claimed: ‘Without punk there’d be no U2, no Nirvana, no Cure, no Joy Division or New Order, no Smiths, no Police, no Simple Minds. Without punk there would have been no 2-Tone. Bang go The Specials and Madness. Without punk no electronica – thus no Human League, no Cabaret Voltaire, no Soft Cell.’ Well, up to a point. I’m pretty sure most of them would have emerged in some shape or form anyway, but they might well have sounded appreciably different.

He also made claims for punk exerting a far broader impact on the zeitgeist beyond influencing a few bands. ‘What about the effects on wider culture?’ he wondered. ‘Would Nick Logan have started The Face and that whole world of style magazines? Would Alan McGee have set up Creation? Would Irvine Welsh have written Trainspotting? No punk, no Factory Records, no Haçienda, no Mike Pickering, no house/E-Culture.’

On one level, of course, he was absolutely right. Every movement in popular culture has far-reaching ripples and every new development is shaped by what has gone before, even if is only as a reaction against it. Hence claiming house and ecstasy as a legacy of punk is no more or less valid than claiming it as the offspring of 1967’s original summer of love. Equally, if we’re going to credit punk with having spawned the Haçienda and Pickering’s legendary acid house DJ sets, then presumably we also have to lay at punk’s door the blame for the latter’s involvement with M People.

Yet my argument was never that punk did not make any lasting impact. Rather, it was that that claims that punk represented some kind of unique sea-change or watershed in pop music are vastly overstated. Popular culture needs a kick up the pants at regular intervals – in fact, every time its latest manifestation gets lazy, formulaic and complacent – pretty much without fail, someone comes along to deliver it. In 1977 it was the Sex Pistols and Never Mind The Bollocks. But they weren’t the first or the last to turn music on its head and, if we’re lucky, there will still be several more such revolutions to come. Of course, there’s another theory which holds that, having passed its half century, rock ‘n’ roll is now a geriatric form, like jazz, that is no longer capable of innovation or reinventing itself. But that’s another argument, for another day – and another book.

© Nigel Williamson 2006

Nigel Williamson

Nigel Williamson began his career in journalism as a reporter for The Tribune, before joining The Times in 1989, then moving into music writing. Nigel is now a contributing editor to Uncut and writes on music for The Times, The Observer, The Guardian and other publications. He is also the author of Journey Through The Past: The Stories Behind The Classic Songs Of Neil Young (Backbeat, 2003), The Rough Guide To Bob Dylan (Rough Guides, 2004), and The Rough Guide To The Blues, which is due for publication in 2006. Currently, Williamson is writing a book about the making of the seminal Rolling Stones album, Beggar’s Banquet.